Reenactment of a Viking landing in L'Anse aux Meadows

Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories relate to visits or interactions with the Americas, indigenous peoples of the Americas, or both; by people from Africa, Asia, Europe, or Oceania; at a time before Columbus's first voyage to the Caribbean in 1492. Such contact is generally accepted in prehistory, but has been hotly debated in the historic period.

Two historical cases of pre-Columbian contact are accepted

amongst the scientific and scholarly mainstream. Successful explorations

led to Norse settlement of Greenland and the L'Anse aux Meadows settlement in Newfoundland some 500 years before Christopher Columbus.

The scientific and scholarly responses to other post-prehistory,

pre-Columbian contact claims have varied. Some such contact claims are

examined in reputable peer-reviewed sources. Other contact claims,

typically based on circumstantial and ambiguous interpretations of

archaeological finds, cultural comparisons, comments in historical

documents, and narrative accounts, have been dismissed as fringe science or pseudoarcheology.

Norse trans-oceanic contact

Co-discoverer Anne Stine Ingstad examines a fire pit at L'Anse aux Meadows in 1963.

Norse journeys to Greenland and Canada are supported by historical and archaeological evidence. A Norse colony in Greenland was established in the late 10th century, and lasted until the mid 15th century, with court and parliament assemblies (þing) taking place at Brattahlíð and a bishop at Garðar. The remains of a Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, were discovered in 1960 and are dated to around the year 1000 (carbon dating estimate 990–1050 CE), L'Anse aux Meadows is the only site widely accepted as evidence of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. It was named a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1978. It is also notable for its possible connection with the attempted colony of Vinland established by Leif Erikson around the same period or, more broadly, with Norse exploration of the Americas.

Few sources describing contact between indigenous peoples and Norse people exist. Contact between the Thule people (ancestors of the modern Inuit) and Norse between the 12th or 13th centuries is known. The Norse Greenlanders called these incoming settlers "skrælingar". Conflict between the Greenlanders and the "skrælings" is recorded in the Icelandic Annals.

The term skrælings is also used in the Vínland sagas, which relate to

events during the 10th century, when describing trade and conflict with

native peoples.

Claims of Polynesian contact

Claims involving sweet potato

The sweet potato, which is native to the Americas, was widespread in Polynesia when Europeans first reached the Pacific. Sweet potato has been radiocarbon-dated in the Cook Islands to 1000 CE, and current thinking is that it was brought to central Polynesia c. 700 CE and spread across Polynesia from there.

It has been suggested that it was brought by Polynesians who had

traveled to South America and back, or that South Americans brought it

to the Pacific. It is possible that the plant could successfully float across the ocean if discarded from the cargo of a boat. Phylogenetic

analysis supports the hypothesis of at least two separate introductions

of sweet potatoes from South America into Polynesia, including one

before and one after European contact.

Claims involving Peruvian mummies

A team of academics headed by the University of York's Mummy Research Group and BioArch, while examining a Peruvian mummy at the Bolton Museum, found that it had been embalmed using a tree resin. Before this it was thought that Peruvian mummies were naturally preserved. The resin, found to be that of an Araucaria conifer related to the 'monkey puzzle tree', was from a variety found only in Oceania and probably New Guinea. "Radiocarbon dating of both the resin and body by the University of Oxford's radiocarbon laboratory confirmed they were essentially contemporary, and date to around CE 1200."

Claims involving California canoes

‘Elye’wun, a reconstructed Chumash tomol

Researchers including Kathryn Klar and Terry Jones have proposed a theory of contact between Hawaiians and the Chumash people of Southern California between 400 and 800 CE. The sewn-plank canoes crafted by the Chumash and neighboring Tongva

are unique among the indigenous peoples of North America, but similar

in design to larger canoes used by Polynesians for deep-sea voyages. Tomolo'o, the Chumash word for such a craft, may derive from kumula'au, the Hawaiian term for the logs from which shipwrights carve planks to be sewn into canoes. The analogous Tongva term, tii'at,

is unrelated. If it occurred, this contact left no genetic legacy in

California or Hawaii. This theory has attracted limited media attention

within California, but most archaeologists of the Tongva and Chumash

cultures reject it on the grounds that the independent development of

the sewn-plank canoe over several centuries is well-represented in the

material record.

Claims involving chickens

The

existence of chicken bones dating from 1321 to 1407 in Chile and

thought to be genetically linked to South Pacific Island chicken landraces suggested further evidence of South Pacific contact with South America. The genetic link between the South American Mapuche (to whom the chickens were thought to originally belong)

chicken bones and South Pacific Island species has been rejected by a

more recent genetic study which concluded that "The analysis of ancient

and modern specimens reveals a unique Polynesian genetic signature" and

that "a previously reported connection between pre-European South

America and Polynesian chickens most likely resulted from contamination

with modern DNA, and that this issue is likely to confound ancient DNA

studies involving haplogroup E chicken sequences."

In recent years, evidence has emerged suggesting a possibility of pre-Columbian contact between the Mapuche people (Araucanians) of south-central Chile and Polynesians. Chicken bones found at the site El Arenal in the Arauco Peninsula, an area inhabited by Mapuche, support a pre-Columbian introduction of chicken to South America.

The bones found in Chile were radiocarbon-dated to between 1304

and 1424, before the arrival of the Spanish. Chicken DNA sequences taken

were matched to those of chickens in American Samoa and Tonga, and dissimilar to European chicken.

However, a later report in the same journal looking at the same mtDNA

concluded that the Chilean chicken specimen clusters with the same

European/Indian subcontinental/Southeast Asian sequences, providing no

support for a Polynesian introduction of chickens to South America.

Linguistics

Sweet potatoes for sale, Thames, New Zealand. The name "kumara" has entered New Zealand English from Māori, and is in wide use.

Dutch linguists and specialists in Amerindian languages Willem Adelaar

and Pieter Muysken have suggested that two lexical items may be shared

by Polynesian languages and languages of South America. One is the name

of the sweet potato, which was domesticated in the New World. Proto-Polynesian *kumala (compare Easter Island kumara, Hawaiian ʻuala, Māori kumāra; apparent cognates outside Eastern Polynesian may be borrowed from Eastern Polynesian languages, calling Proto-Polynesian status and age into question) may be connected with Quechua and Aymara k’umar ~ k’umara. A possible second is the word for 'stone axe', Easter Island toki, New Zealand Maori toki 'adze', Mapuche toki, and further afield, Yurumanguí totoki 'axe'.

According to Adelaar and Muysken, the similarity in the word for

sweet potato "constitutes near proof of incidental contact between

inhabitants of the Andean region and the South Pacific", though

according to Adelaar and Muysken the word for axe is not as convincing.

The authors argue that the presence of the word for sweet potato

suggests sporadic contact between Polynesia and South America, but no

migrations.

Similarity of features and genetics

Mocha Island off the coast of Arauco Peninsula, Chile

In December 2007, several human skulls were found in a museum in Concepción, Chile. These skulls originated from Mocha Island, an island just off the coast of Chile in the Pacific Ocean, formerly inhabited by the Mapuche. Craniometric analysis of the skulls, according to Lisa Matisoo-Smith of the University of Otago and José Miguel Ramírez Aliaga of the Universidad de Valparaíso, suggests that the skulls have "Polynesian features" – such as a pentagonal shape when viewed from behind, and rocker jaws.

From 2007 to 2009, geneticist Erik Thorsby and colleagues have published two studies in Tissue Antigens

that evidence an Amerindian genetic contribution to the Easter Island

population, determining that it was probably introduced before European

discovery of the island.

In 2014, geneticist Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas of The Center for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen published a study in Current Biology that found human genetic evidence of contact between the populations of Easter Island and South America, approximately 600 years ago (i.e. 1400 CE ± 100 years).

Some members of the now extinct Botocudo people, who lived in the interior of Brazil, were found in research published in 2013 to have been members of mtDNA haplogroup B4a1a1, which is normally found only among Polynesians and other subgroups of Austronesians. This was based on an analysis of fourteen skulls. Two belonged to B4a1a1 (while twelve belonged to subclades of mtDNA Haplogroup C1

common among Native Americans). The research team examined various

scenarios, none of which they could say for certain were correct. They

dismissed a scenario of direct contact in prehistory between Polynesia

and Brazil as "too unlikely to be seriously entertained." While B4a1a1

is also found among the Malagasy people of Madagascar

(which experienced significant Austronesian settlement in prehistory),

the authors described as "fanciful" suggestions that B4a1a1 among the

Botocudo resulted from the African slave trade (which included

Madagascar).

A genetic study published in Nature in July 2015 stated that "some Amazonian Native Americans descend partly from a ... founding population that carried ancestry more closely related to indigenous Australians, New Guineans and Andaman Islanders than to any present-day Eurasians or Native Americans". The authors, who included David Reich,

added: "This signature is not present to the same extent, or at all, in

present-day Northern and Central Americans or in a ~12,600-year-old

Clovis-associated genome, suggesting a more diverse set of founding

populations of the Americas than previously accepted." This appears to

conflict with an article published roughly simultaneously in Science

which adopts the previous consensus perspective. The ancestors of all

Native Americans entered the Americas as a single migration wave from

Siberia no earlier than ~23 ka,

separate from the Inuit and diversified into "northern" and "southern"

Native American branches ~13 ka. There is evidence of post-divergence

gene flow between some Native Americans and groups related to East

Asians/Inuit and Australo-Melanesians.

Claims of East Asian contact

Claims of contact with Alaska

Similar cultures of peoples across the Bering Strait in both Siberia and Alaska suggest human travel between the two places ever since the strait was formed. After Paleo-Indians arrived during the Ice Age and began the settlement of the Americas, a second wave of people from Asia came to Alaska around 8000 BC. These "Na-Dene"

peoples, who share many linguistic and genetic similarities not found

in other parts of the Americas, populated the far north of the Americas

and only made it as far south as Oasisamerica. It is suggested that by 4000 BC "Eskimo"

peoples began coming to the Americas from Siberia. "Eskimo" tribes live

today in both Asia and North America and there is much evidence they

lived in Asia even in prehistoric times.

Bronze artifacts discovered in a 1,000-year-old house in Alaska

suggest pre-Columbian trade. Bronze working had not been developed in

Alaska at the time and suggest the bronze came from nearby Asia—possibly

China, Korea, or Russia. Also inside the house were found the remains

of obsidian artifacts, which have a chemical signature that indicates

the obsidian is from the Anadyr River valley in Russia.

In June 2016, Purdue University

published the results of research on six metal and composite metal

artifacts excavated from a late prehistoric archaeological context at Cape Espenberg on the northern coast of the Seward Peninsula in Alaska. Also part of the research team was Robert J. Speakman, of the Center for Applied Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia, and Victor Mair, of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Pennsylvania.

The report is the first evidence that metal from Asia reached

prehistoric North America before the contact with Europeans, stating

that X-ray fluorescence

identified two of these artifacts as smelted industrial alloys with

large proportions of tin and lead. The presence of smelted alloys in a

prehistoric Inuit context in northwest Alaska was demonstrated for the

first time and indicates the movement of Eurasian metal across the

Bering Strait into North America before sustained contact with

Europeans.

This is not a surprise based on oral history and other archaeological finds, and it was just a matter of time before we had a good example of Eurasian metal that had been traded [...] We believe these smelted alloys were made somewhere in Eurasia and traded to Siberia and then traded across the Bering Strait to ancestral Inuits [sic] people, also known as Thule culture, in Alaska. Locally available metal in parts of the Arctic, such as native metal, copper and meteoritic and telluric iron were used by ancient Inuit people for tools and to sometimes indicate status. Two of the Cape Espenberg items that were found – a bead and a buckle — are heavily leaded bronze artifacts. Both are from a house at the site dating to the Late Prehistoric Period, around 1100-1300 AD, which is before sustained European contact in the late 18th century. [...] The belt buckle also is considered an industrial product and is an unprecedented find for this time. It resembles a buckle used as part of a horse harness that would have been used in north-central China during the first six centuries before the Common Era.

— H. Kory Cooper, Associate Professor of Anthropology.

Claims of contact with Ecuador

A 2013 genetic study suggests the possibility of contact between Ecuador and East Asia.

The study suggests that the contact could have been trans-oceanic or a

late-stage coastal migration that did not leave genetic imprints in

North America.

Claims of Chinese contact

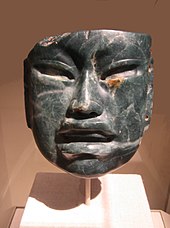

A jade Olmec mask from Central America. Gordon Ekholm, who was an eminent archaeologist and curator at the American Museum of Natural History, suggested that the Olmec art style might have originated in Bronze Age China.

Other researchers have argued that the Olmec civilization came into existence with the help of Chinese refugees, particularly at the end of the Shang dynasty. In 1975, Betty Meggers of the Smithsonian Institution argued that the Olmec civilization originated due to Shang Chinese influences around 1200 BCE. In a 1996 book, Mike Xu, with the aid of Chen Hanping, claimed that celts from La Venta bear Chinese characters. These claims are unsupported by mainstream Mesoamerican researchers.

Other claims have been made for early Chinese contact with North America.

In 1882 artifacts identified at the time as Chinese coins were

discovered in British Columbia. A contemporary account states that:

In the summer of 1882 a miner found on De Foe (Deorse?) creek, Cassiar district, Br. Columbia, thirty Chinese coins in the auriferous sand, twenty-five feet below the surface. They appeared to have been strung, but on taking them up the miner let them drop apart. The earth above and around them was as compact as any in the neighborhood. One of these coins I examined at the store of Chu Chong in Victoria. Neither in metal nor markings did it resemble the modern coins, but in its figures looked more like an Aztec calendar. So far as I can make out the markings, this is a Chinese chronological cycle of sixty years, invented by Emperor Huungti, 2637 BCE, and circulated in this form to make his people remember it.

In 1885, a vase containing similar discs was also discovered, wrapped in the roots of a tree around 300 years old. Grant Keddie, Curator of Archeology at the Royal B.C. Museum,

examined a photograph of a coin from Cassiar taken in the 1940s

(whereabouts now unknown) and he believes that the character style and

the evidence that it was machine-ground show it to be a 19th-century

copy of a Ming Dynasty temple token.

A group of Chinese Buddhist missionaries led by Hui Shen before 500 CE claimed to have visited a location called Fusang. Although Chinese mapmakers placed this territory on the Asian coast, others have suggested as early as the 1800s

that Fusang might have been in North America, due to perceived

similarities between portions of the California coast and Fusang as

depicted by Asian sources.

In his book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, the British author Gavin Menzies made the controversial claim that the fleet of Zheng He arrived in America in 1421.

Professional historians contend that Zheng He reached the eastern coast

of Africa, and dismiss Menzies's hypothesis as entirely without proof.

In 1973 and 1975 doughnut-shaped stones were discovered off the

coast of California that resembled stone anchors used by Chinese

fishermen. These (sometimes called the Palos Verdes stones) were

initially thought to be up to 1500 years old and proof of pre-Columbian

contact by Chinese sailors. Later geological investigations showed them

to be a local rock known as Monterey shale, and they are thought to have been used by Chinese settlers fishing off the coast in the nineteenth century.

Claims of Japanese contact

Otokichi, a Japanese castaway in America in 1834, depicted here in 1849.

Smithsonian archaeologist Betty Meggers wrote that pottery associated with the Valdivia culture of coastal Ecuador dated to 3000–1500 BCE exhibited similarities to pottery produced during the Jōmon period in Japan, arguing that contact between the two cultures might explain the similarities. Chronological and other problems have led most archaeologists to dismiss this idea as implausible.

The suggestion has been made that the resemblances (which are not

complete) are simply due to the limited number of designs possible when

incising clay.

Alaskan anthropologist Nancy Yaw Davis claims that the Zuni people of New Mexico exhibit linguistic and cultural similarities to the Japanese. The Zuni language is a linguistic isolate, and Davis contends that the culture appears to differ from that of the surrounding natives in terms of blood type, endemic disease, and religion. Davis speculates that Buddhist priests or restless peasants from Japan may have crossed the Pacific in the 13th century, traveled to the American Southwest, and influenced Zuni society.

In the 1890s, lawyer and politician James Wickersham

argued that pre-Columbian contact between Japanese sailors and Native

Americans was highly probable, given that from the early 17th century to

the mid-19th century several dozen Japanese ships were carried from

Asia to North America along the powerful Kuroshio Currents. Such Japanese ships landed from the Aleutian Islands in the north to Mexico

in the south, carrying a total of 293 persons in the 23 cases where

head-counts were given in historical records. In most cases, the

Japanese sailors gradually made their way home on merchant vessels. In

1834 a dismasted, rudderless Japanese ship crashed near Cape Flattery. Three survivors of the ship were enslaved by Makahs for a period before being rescued by members of the Hudson's Bay Company. They were never able to return to their homeland due to Japan's isolationist policy. Another Japanese ship crashed in about 1850 near the mouth of the Columbia River,

Wickersham writes, and the sailors were assimilated into the local

Native American population. While admitting there was no definitive

proof of pre-Columbian contact between Japanese and North Americans,

Wickersham thought it implausible that such contacts as outlined above

would have started only after Europeans arrived in North America.

Claims of Indian contact

In 1879, Alexander Cunningham described the carvings on the Stupa of Bharhut from c. 200 BCE and described some fruit like detail as a custard-apple (Annona squamosa). He wasn't aware that this plant, indigenous to the Americas was introduced to India after Vasco da Gama's

discovery of the sea route in 1498 and the problem was pointed out to

him. A 2009 study claimed to have found carbonized remains that date to

2000 BCE and appear like the seeds of custard apple.

Copán stela B detail highlighted by Grafton Smith

Grafton Elliot Smith claimed that certain details in the Mayan stelae at Copán represented an Asian elephant. He wrote Elephants and Ethnologists,

a book on the topic in 1924. Contemporary archaeologists suggested that

it was based on a tapir and his suggestions have generally been

dismissed by subsequent research.

The Somnathpur figures at the sides hold maize-like objects in their left hands

Some carving details from around the 12th century in Karnataka that appeared like ears of maize (Zea mays), a crop from the New World, were interpreted by Carl Johannessen in 1989 as evidence of pre-Columbian contact.

These suggestions were dismissed by multiple Indian researchers based

on several lines of evidence. The object has been claimed by some to

represent a "Muktaphala", an imaginary fruit bedecked with pearls.

Claims of African and Middle Eastern contact

Claims involving African contact

Proposed claims for an African presence in Mesoamerica stem from attributes of the Olmec culture, the claimed transfer of African plants to the Americas, interpretations of European and Arabic historical accounts and certain genetic studies of Mexican populations.

The Olmec culture existed from roughly 1200 BCE to 400 BCE. The idea

that the Olmecs are related to Africans was suggested by José Melgar,

who discovered the first colossal head at Hueyapan (now Tres Zapotes) in 1862. More recently, Ivan Van Sertima

has presented multiple lines of evidence to suggest an African

influence on Mesoamerican culture. His views have been the target of

severe scholarly criticism by those in the academic mainstream.

Leo Wiener's "Africa and the Discovery of America" suggests similarities between Mandinka

and native Mesoamerican religious symbols such as the winged serpent

and the sun disk, or Quetzalcoatl, and words that have Mande roots and

share similar meanings across both cultures such as "kore", "gadwal",

and "qubila" (in Arabic) or "kofila" (in Mandinka).

North African sources describe what some consider to be visits to the New World by a Mali fleet in 1311.

According to the abstract of Columbus's log made by Bartolomé de las Casas, the purpose of Columbus’s third voyage was to test both the claims of King John II of Portugal

that "canoes had been found which set out from the coast of Guinea

[West Africa] and sailed to the west with merchandise" as well as the

claims of the native inhabitants of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola

that "from the south and the southeast had come black people whose

spears were made of a metal called guanín...from which it was found that of 32 parts: 18 were gold, 6 were silver, and 8 copper." Another supporting claim was made by Washington Irving, in his "Life of Columbus", who wrote that in 1503 when Columbus was on the Mosquito Coast

"There was no pure gold to be met with here, all their ornaments were

of guanin; but the natives assured the Adelantado that in proceeding

along the coast, the ships would soon arrive at a country where gold was

in great abundance."

Claims of Pre-Clovis immigration from Africa

Brazilian researcher Niede Guidon, who led the Pedra Furada

sites excavations "... said she believed that humans … might have come

not overland from Asia but by boat from Africa", with the journey taking

place 100,000 years ago. Michael R. Waters, a geoarchaeologist at Texas A&M University noted the absence of genetic evidence in modern populations to support Guidon's claim.

Claims involving Arab contact

Early Chinese accounts of Muslim expeditions state that Muslim sailors reached a region called Mulan Pi ("magnolia skin") (Chinese: 木蘭皮; pinyin: Mùlán Pí; Wade–Giles: Mu-lan-p'i). Mulan Pi is mentioned in Lingwai Daida (1178) by Zhou Qufei and Zhufan Zhi (1225) by Chao Jukua, together referred to as the "Sung Document". Mulan Pi is normally identified as Spain of the Almoravid dynasty (Al-Murabitun), though some fringe theories hold that it is instead some part of the Americas.

One supporter of the interpretation of Mulan Pi as part of the Americas was historian Hui-lin Li in 1961, and while Joseph Needham

was also open to the possibility, he doubted that Arab ships at the

time would have been able to withstand a return journey over such a long

distance across the Atlantic Ocean and points out that a return journey

would have been impossible without knowledge of prevailing winds and

currents.

According to Muslim historian Abu al-Hasan 'Alī al-Mas'ūdī (871-957), Khashkhash Ibn Saeed Ibn Aswad (Arabic: خشخاش بن سعيد بن اسود) sailed over the Atlantic Ocean and discovered a previously unknown land (أرض مجهولة Ard Majhoola) in 889 and returned with a shipload of valuable treasures.

Claims involving ancient Phoenician contact

Using gold obtained by expansion of the African coastal trade down the west African coast, the Phoenician state of Carthage minted gold staters in 350 BCE bearing a pattern, in the reverse exergue of the coins, interpreted as a map of the Mediterranean with the Americas shown to the west across the Atlantic.

Reports of the discovery of putative Carthaginian coins in North

America are based on modern replicas, that may have been buried at sites

from Massachusetts to Nebraska in order to confuse and mislead

archaeological investigation.

Claims involving ancient Judaic contact

The Bat Creek inscription and Los Lunas Decalogue Stone have led some to suggest the possibility that Jewish seafarers may have come to America after fleeing the Roman Empire at the time of the Jewish Revolt.

Scholar Cyrus H. Gordon believed that Phoenicians and other Semitic groups had crossed the Atlantic in antiquity, ultimately arriving in both North and South America. This opinion was based on his own work on the Bat Creek inscription. Similar ideas were also held by John Philip Cohane; Cohane even claimed that many geographical names in America have a Semitic origin.

Claims of European contact

Solutrean hypothesis

Examples of Clovis and other Paleoindian point forms, markers of archaeological cultures in northeastern North America

The Solutrean hypothesis argues that Europeans migrated to the New World during the Paleolithic

era, circa 16,000 to 13,000 BCE. This hypothesis proposes contact

partly on the basis of perceived similarities between the flint tools of

the Solutrean culture in modern-day France, Spain and Portugal (which thrived circa 20,000 to 15,000 BCE), and the Clovis culture of North America, which developed circa 9000 BCE.

The Solutrean hypothesis was proposed in the mid-1990s. It has little support amongst the scientific community, and genetic markers are inconsistent with the idea.

Claims involving ancient Roman contact

Evidence of contacts with the civilizations of Classical Antiquity—primarily with the Roman Empire,

but sometimes also with other cultures of the age—have been based on

isolated archaeological finds in American sites that originated in the

Old World. The Bay of Jars in Brazil has been yielding ancient clay

storage jars that resemble Roman amphorae

for over 150 years. It has been proposed that the origin of these jars

is a Roman wreck, although it has been suggested that they could be 15th

or 16th century Spanish olive oil jars.

Romeo Hristov argues that a Roman ship, or the drifting of such a

shipwreck to the American shores, is a possible explanation of

archaeological finds (like the Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca bearded head) from

ancient Rome in America. Hristov claims that the possibility of such an

event has been made more likely by the discovery of evidences of travels

by Romans to Tenerife and Lanzarote in the Canaries, and of a Roman settlement (from the 1st century BCE to the 4th century CE) on Lanzarote island.

Floor

mosaic depicting a fruit which looks like a pineapple. Opus

vermiculatum, Roman artwork of the end of the 1st century BC/begin of

the 1st century AD.

In 1950, an Italian botanist, Domenico Casella, suggested that a depiction of a pineapple was represented among wall paintings of Mediterranean fruits at Pompeii. According to Wilhelmina Feemster Jashemski, this interpretation has been challenged by other botanists, who identify it as a pine cone from the Umbrella pine tree, which is native to the Mediterranean area.

Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca head

A small terracotta head sculpture, with a beard and European-like features, was found in 1933 (in the Toluca Valley, 72 kilometres southwest of Mexico City) in a burial offering under three intact floors of a pre-colonial

building dated to between 1476 and 1510. The artifact has been studied

by Roman art authority Bernard Andreae, director emeritus of the German

Institute of Archaeology in Rome, Italy, and Austrian anthropologist Robert von Heine-Geldern,

both of whom stated that the style of the artifact was compatible with

small Roman sculptures of the 2nd century. If genuine and if not placed

there after 1492 (the pottery found with it dates to between 1476 and

1510) the find provides evidence for at least a one-time contact between the Old and New Worlds.

According to ASU's Michael E. Smith,

John Paddock, a leading Mesoamerican scholar, used to tell his classes

in the years before he died that the artifact was planted as a joke by

Hugo Moedano, a student who originally worked on the site. Despite

speaking with individuals who knew the original discoverer (García

Payón), and Moedano, Smith says he has been unable to confirm or reject

this claim. Though he remains skeptical, Smith concedes he cannot rule

out the possibility that the head was a genuinely buried Post-classic

offering at Calixtlahuaca.

14th- and 15th-century Europe contact

Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney and feudal baron of Roslin (c. 1345 – c. 1400) was a Scottish nobleman. He is best known today because of a modern legend that he took part in explorations of Greenland and North America almost 100 years before Christopher Columbus. In 1784, he was identified by Johann Reinhold Forster as possibly being the Prince Zichmni described in letters allegedly written around the year 1400 by the Zeno brothers of Venice, in which they describe a voyage throughout the North Atlantic under the command of Zichmni.

Henry was the grandfather of William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness, the builder of Rosslyn Chapel (near Edinburgh, Scotland). The authors Robert Lomas and Christopher Knight believe some carvings in the chapel to be ears of New World corn or maize.

This crop was unknown in Europe at the time of the chapel's

construction, and was not cultivated there until several hundred years

later. Knight and Lomas view these carvings as evidence supporting the

idea that Henry Sinclair travelled to the Americas well before Columbus.

In their book they discuss meeting with the wife of the botanist Adrian

Dyer, and that Dyer's wife told him that Dyer agreed that the image

thought to be maize was accurate.

In fact Dyer found only one identifiable plant among the botanical

carvings and suggested that the "maize" and "aloe" were stylized wooden

patterns, only coincidentally looking like real plants. Specialists in medieval architecture interpret these carvings as stylised depictions of wheat, strawberries or lilies.

A 1547 edition of Oviedo's La historia general de las Indias.

Some have conjectured that Columbus was able to persuade the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon

to support his planned voyage only because they were aware of some

recent earlier voyage across the Atlantic. Some suggest that Columbus

himself visited Canada or Greenland before 1492, because according to Bartolomé de las Casas he wrote he had sailed 100 leagues past an island he called Thule in 1477. Whether he actually did this and what island he visited, if any, is uncertain. Columbus is thought to have visited Bristol in 1476. Bristol was also the port from which John Cabot

sailed in 1497, crewed mostly by Bristol sailors. In a letter of late

1497 or early 1498 the English merchant John Day wrote to Columbus about

Cabot's discoveries, saying that land found by Cabot was "discovered in

the past by the men from Bristol who found 'Brasil' as your lordship

knows". There may be records of expeditions from Bristol to find the "isle of Brazil" in 1480 and 1481. Trade between Bristol and Iceland is well documented from the mid 15th century.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés records several such legends in his General y natural historia de las Indias

of 1526, which includes biographical information on Columbus. He

discusses the then-current story of a Spanish caravel that was swept off

its course while on its way to England, and wound up in a foreign land

populated by naked tribesmen. The crew gathered supplies and made its

way back to Europe, but the trip took several months and the captain and

most of the men died before reaching land. The ship's pilot, a man

called Alonso Sánchez,

and very few others finally made it to Portugal, but all were very ill.

Columbus was a good friend of the pilot, and took him to be treated in

his own house, and the pilot described the land they had seen and marked

it on a map before dying. People in Oviedo's time knew this story in

several versions, but Oviedo regarded it as myth.

In 1925, Soren Larsen wrote a book claiming that a joint

Danish-Portuguese expedition landed in Newfoundland or Labrador in 1473

and again in 1476. Larsen claimed that Didrik Pining and Hans Pothorst served as captains, while João Vaz Corte-Real and the possibly mythical John Scolvus served as navigators, accompanied by Álvaro Martins. Nothing beyond circumstantial evidence has been found to support Larsen's claims.

The historical record shows that Basque fishermen were present in Newfoundland and Labrador

from at least 1517 onwards (therefore predating the first recorded

European settlements in the region). The Basques' fishing expeditions

led to significant trade and cultural exchanges between them and Native

Americans. A fringe theory suggests that Basque sailors may have first

arrived to North America before Columbus' voyages to the New World (some

sources suggest the late 14th century as a tentative date), but kept

the destination a secret in order to avoid competition over the fishing

resources in the North American coasts. There is no historical or

archaeological evidence to support this claim.

Irish and Welsh legends

Saint Brendan and the whale. From a 15th-century manuscript.

The legend of Saint Brendan,

an Irish monk, involves a fantastical journey into the Atlantic Ocean

in search of Paradise in the 6th century. Since the discovery of the New

World, various authors have tried to link the Brendan legend with an

early discovery of America. In 1977 The voyage was successfully

recreated by Tim Severin using a replica of an ancient Irish currach.

According to a British myth, Madoc

was a prince from Wales who explored the Americas as early as 1170.

While most scholars consider this legend to be untrue, it was used as

justification for British claims to the Americas, based on the notion of

a Briton arriving before other European nationalities.

Biologist and controversial amateur epigrapher Barry Fell claims that Irish Ogham writing has been found carved into stones in the Virginias. Linguist David H. Kelley

has criticized some of Fell's work but nonetheless argued that genuine

Celtic Ogham inscriptions have in fact been discovered in America. However, others have raised serious doubts about these claims.

Claims of trans-oceanic travel originating from the New World

Claims of Egyptian coca and tobacco

The mummy of Ramesses II

Traces of coca and nicotine found in some Egyptian mummies have led to speculation that Ancient Egyptians may have had contact with the New World. The initial discovery was made by a German toxicologist, Svetlana Balabanova, after examining the mummy of a priestess called Henut Taui. Follow-up tests of the hair shaft, performed to rule out contamination, gave the same results.

A television show reported that examination of numerous Sudanese mummies undertaken by Balabanova mirrored what was found in the mummy of Henut Taui.

Balabanova suggested that the tobacco may be accounted for since it may

have also been known in China and Europe, as indicated by analysis run

on human remains from those respective regions. Balabanova proposed that

such plants native to the general area may have developed

independently, but have since gone extinct. Other explanations include fraud, though curator Alfred Grimm of the Egyptian Museum in Munich disputes this. Skeptical of Balabanova's findings, Rosalie David, Keeper of Egyptology at the Manchester Museum,

had similar tests performed on samples taken from the Manchester mummy

collection and reported that two of the tissue samples and one hair

sample did test positive for nicotine. Sources of nicotine other than tobacco and sources of cocaine in the Old World are discussed by the British biologist Duncan Edlin.

Mainstream scholars remain skeptical, and they do not see this as

proof of ancient contact between Africa and the Americas, especially

because there may be possible Old World sources.

Two attempts to replicate Balabanova's finds of cocaine failed,

suggesting "that either Balabanova and her associates are

misinterpreting their results or that the samples of mummies tested by

them have been mysteriously exposed to cocaine."

A re-examination in the 1970s of the mummy of Ramesses II

revealed the presence of fragments of tobacco leaves in its abdomen.

This became a popular topic in fringe literature and the media and was

seen as proof of contact between Ancient Egypt and the New World. The

investigator, Maurice Bucaille,

noted that when the mummy was unwrapped in 1886 the abdomen was left

open and that "it was no longer possible to attach any importance to the

presence inside the abdominal cavity of whatever material was found

there, since the material could have come from the surrounding

environment."

Following the renewed discussion of tobacco sparked by Balabanova's

research and its mention in a 2000 publication by Rosalie David, a study

in the journal Antiquity

suggested that reports of both tobacco and cocaine in mummies "ignored

their post-excavation histories" and pointed out that the mummy of

Ramesses II had been moved five times between 1883 and 1975.

Icelander DNA finding

In

2010 Sigríður Sunna Ebenesersdóttir published a genetic study showing

that over 350 living Icelanders carried mitochondrial DNA of a new type

that is similar to the type found only in Native American and East Asian

populations. Using the deCODE genetics

database, Sigríður Sunna determined that the DNA entered the Icelandic

population not later than 1700, and likely several centuries earlier.

However Sigríður Sunna also states that "...while a Native American

origin seems most likely for [this new haplogroup], an Asian or European

origin cannot be ruled out".

Norse legends and sagas

Statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni.

In 1009, legends report that Norse explorer Thorfinn Karlsefni abducted two children from Markland,

an area on the North American mainland where Norse explorers visited

but did not settle. The two children were then taken to Greenland, where

they were baptized and taught to speak Norse.

In 1420, Danish geographer Claudius Clavus Swart wrote that he personally had seen "pygmies" from Greenland who were caught by Norsemen in a small skin boat. Their boat was hung in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim

along with another, longer boat also taken from "pygmies". Clavus

Swart's description fits the Inuit and two of their types of boats, the kayak and the umiak. Similarly, the Swedish clergyman Olaus Magnus wrote in 1505 that he saw in Oslo Cathedral two leather boats taken decades earlier. According to Olaus, the boats were captured from Greenland pirates by one of the Haakons, which would place the event in the 14th century.

In Ferdinand Columbus's biography of his father Christopher, he says that in 1477 his father saw in Galway, Ireland

two dead bodies which had washed ashore in their boat. The bodies and

boat were of exotic appearance, and have been suggested to have been Inuit who had drifted off course.

Inuit

It has been

suggested that the Norse took other indigenous peoples to Europe as

slaves over the following centuries, because they are known to have

taken Scottish and Irish slaves.

There is also evidence of Inuit coming to Europe under their own

power or as captives after 1492. A substantial body of Greenland Inuit

folklore first collected in the 19th century told of journeys by boat to

Akilineq, here depicted as a rich country across the ocean.

Pre-Columbian contact between Alaska and Kamchatka via the subarctic Aleutian Islands

would have been conceivable, but the two settlement waves on this

archipelago started on the American side and its western continuation,

the Commander Islands, remained uninhabited until after Russian explorers encountered the Aleut people in 1741. There is no genetic or linguistic evidence for earlier contact along this route.

Religious claims

17th-century speculation

In 1650, a British preacher in Norfolk, Thomas Thorowgood, published Jewes in America or Probabilities that the Americans are of that Race, for the New England missionary society. Tudor Parfitt writes:

The society was active in trying to convert the Indians but suspected that they might be Jews and realized they better be prepared for an arduous task. Thorowgood's tract argued that the native population of North America were descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes.

In 1652 Sir Hamon L'Estrange, an English author writing on history and theology, published Americans no Jews, or improbabilities that the Americans are of that Race

in response to the tract by Thorowgood. In response to L'Estrange,

Thorowgood published a second edition of his book in 1660 with a revised

title and included a foreword written by John Eliot, a Puritan missionary who had translated the Bible into an Indian language.

Mormon teachings

The Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the Latter Day Saint movement published by founder and leader Joseph Smith Jr

in 1830 at the age of twenty-four, states that some ancient inhabitants

of the New World are descendants of Semitic peoples who sailed from the

Old World. Mormon groups such as the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies attempt to study and expand on these ideas. Scientific consensus rejects these claims.

The National Geographic Society, in a 1998 letter to the Institute for Religious Research,

stated "Archaeologists and other scholars have long probed the

hemisphere's past and the society does not know of anything found so far

that has substantiated the Book of Mormon."

Some LDS scholars hold the view that archaeological study of Book

of Mormon claims are not meant to vindicate the literary narrative. For

example, Terryl Givens,

professor of English at the University of Richmond, points out that

there is a lack of historical accuracy in the Book of Mormon in relation

to modern archaeological knowledge.

In the 1950s, Professor M. Wells Jakeman popularized a belief that the Izapa Stela 5 represents the Book of Mormon prophets Lehi and Nephi's tree of life vision, and was a validation of the historicity of the claims of pre-Columbian settlement in the Americas. His interpretations of the carving and its connection to pre-Columbian contact have been disputed. Since that time, scholarship on the Book of Mormon has concentrated on cultural parallels rather than "smoking gun" sources.