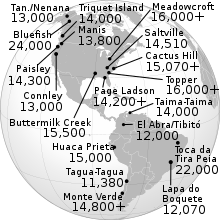

Map

of the earliest securely dated sites showing human presence in the

Americas, 16–13 ka for North America and 15–11 ka for South America.

The first settlement of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers first entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum.

These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and rapidly throughout both North and South America, by 14,000 years ago. The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians.

The peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question, and while advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have shed progressively more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.

While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled

from Asia, the pattern of migration, its timing, and the place(s) of

origin in Eurasia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remain

unclear.

The prevalent migration models outline different time frames for

the Asian migration from the Bering Straits and subsequent dispersal of

the founding population throughout the continent. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.

The "Clovis first theory" refers to the 1950s hypothesis that the Clovis culture

represents the earliest human presence in the Americas, beginning about

13,000 years ago; evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated since

2000, pushing back the possible date of the first peopling of the

Americas to about 13,200–15,500 years ago.

The environment during the latest Pleistocene

Emergence and submergence of Beringia

Figure1. Submergence of the Beringian land bridge with post-Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) rise in eustatic sea level

During the Wisconsin Glaciation,

varying portions of the Earth's water were stored as glacier ice. As

water accumulated in glaciers, the volume of water in the oceans

correspondingly decreased, resulting in lowering of global sea level. The variation of sea level over time has been reconstructed using oxygen isotope

analysis of deep sea cores, the dating of marine terraces, and high

resolution oxygen isotope sampling from ocean basins and modern ice

caps. A drop of eustatic sea level by about 60 m to 120 m lower than present-day levels, commencing around 30,000 years BP, created Beringia, a durable and extensive geographic feature connecting Siberia with Alaska. With the rise of sea level after the Last Glacial Maximum

(LGM), the Beringian land bridge was again submerged. Estimates of the

final re-submergence of the Beringian land bridge based purely on

present bathymetry of the Bering Strait and eustatic sea level curve

place the event around 11,000 years BP (Figure 1). Ongoing research

reconstructing Beringian paleogeography during deglaciation could change

that estimate and possible earlier submergence could further constrain

models of human migration into North America.

Glaciers

The

onset of the Last Glacial Maximum after 30,000 years BP saw the

expansion of alpine glaciers and continental ice sheets that blocked

migration routes out of Beringia. By 21,000 years BP, and possibly

thousands of years earlier, the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets coalesced east of the Rocky Mountains, closing off a potential migration route into the center of North America. Alpine glaciers in the coastal ranges and the Alaskan Peninsula isolated the interior of Beringia from the Pacific coast. Coastal alpine glaciers and lobes of Cordilleran ice coalesced into piedmont glaciers that covered large stretches of the coastline as far south as Vancouver Island and formed an ice lobe across the Straits of Juan de Fuca by 15,000 14C years BP (18,000 cal years BP). Coastal alpine glaciers started to retreat around 19,000 cal years BP while Cordilleran ice continued advancing in the Puget lowlands up to 14,000 14C years BP (16,800 cal years BP)

Even during the maximum extent of coastal ice, unglaciated refugia

persisted on present-day islands, that supported terrestrial and marine

mammals. As deglaciation occurred, refugia expanded until the coast became ice-free by 15,000 cal years BP.

The retreat of glaciers on the Alaskan Peninsula provided access from

Beringia to the Pacific coast by around 17,000 cal years BP. The ice barrier between interior Alaska and the Pacific coast broke up starting around 13,500 14C years (16,200 cal years) BP. The ice-free corridor to the interior of North America opened between 13,000 and 12,000 cal years BP.

Glaciation in eastern Siberia during the LGM was limited to alpine and

valley glaciers in mountain ranges and did not block access between

Siberia and Beringia.

Climate and biological environments

The

paleoclimates and vegetation of eastern Siberia and Alaska during the

Wisconsin glaciation have been deduced from high resolution oxygen

isotope data and pollen stratigraphy.

Prior to the Last Glacial Maximum, climates in eastern Siberia

fluctuated between conditions approximating present day conditions and

colder periods. The pre-LGM warm cycles in Arctic Siberia saw flourishes

of megafaunas.

The oxygen isotope record from the Greenland Ice Cap suggests that

these cycles after about 45k years BP lasted anywhere from hundreds to

between one and two thousand years, with greater duration of cold

periods starting around 32k cal years BP. The pollen record from Elikchan Lake, north of the Sea of Okhotsk, shows a marked shift from tree and shrub pollen to herb pollen prior to 26k 14C years BP, as herb tundra replaced boreal forest and shrub steppe going into the LGM.

A similar record of tree/shrub pollen being replaced with herb pollen

as the LGM approached was recovered near the Kolyma River in Arctic

Siberia.

The abandonment of the northern regions of Siberia due to rapid cooling

or the retreat of game species with the onset of the LGM has been

proposed to explain the lack of archaeosites in that region dating to

the LGM.

The pollen record from the Alaskan side shows shifts between herb/shrub

and shrub tundra prior to the LGM, suggesting less dramatic warming

episodes than those that allowed forest colonization on the Siberian

side. Diverse, though not necessarily plentiful, megafaunas were present

in those environments. Herb tundra dominated during the LGM, due to

cold and dry conditions.

Coastal environments during the Last Glacial Maximum were complex. The lowered sea level, and an isostatic

bulge equilibrated with the depression beneath the Cordilleran Ice

Sheet, exposed the continental shelf to form a coastal plain.

While much of the coastal plain was covered with piedmont glaciers,

unglaciated refugia supporting terrestrial mammals have been identified

on Haida Gwaii, Prince of Wales Island, and outer islands of the Alexander Archipelago. The now-submerged coastal plain has potential for more refugia.

Pollen data indicate mostly herb/shrub tundra vegetation in unglaciated

areas, with some boreal forest towards the southern end of the range of

Cordilleran ice. The coastal marine environment remained productive, as indicated by fossils of pinnipeds. The highly productive kelp forests over rocky marine shallows may have been a lure for coastal migration. Reconstruction of the southern Beringian coastline also suggests potential for a highly productive coastal marine environment.

Environmental changes during deglaciation

Pollen data indicate a warm period culminating between 14k and 11k 14C years BP (17k-13k cal years BP) followed by cooling between 11k-10k 14C years BP (13k-11.5k cal years BP).

Coastal areas deglaciated rapidly as coastal alpine glaciers, then

lobes of Cordilleran ice, retreated. The retreat was accelerated as sea

levels rose and floated glacial termini. Estimates of a fully ice-free

coast range between 16k and 15k cal years BP. Littoral

marine organisms colonized shorelines as ocean water replaced glacial

meltwater. Replacement of herb/shrub tundra by coniferous forests was

underway by 12.4k 14C years BP (15k cal years BP) north of

Haida Gwaii. Eustatic sea level rise caused flooding, which accelerated

as the rate grew more rapid.

The inland Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets retreated more

slowly than did the coastal glaciers. Opening of an ice-free corridor

did not occur until after 13k to 12k cal years BP.

The early environment of the ice-free corridor was dominated by glacial

outwash and meltwater, with ice-dammed lakes and periodic flooding from

the release of ice-dammed meltwater. Biological productivity of the deglaciated landscape was gained slowly. The earliest possible viability of the ice-free corridor as a human migration route has been estimated at 11.5k cal years BP.

Birch forests were advancing across former herb tundra in Beringia by 14.3ka 14C years BP (17k cal years BP) in response to climatic amelioration, indicating increased productivity of the landscape.

Chronology and sources of migration

25 kya Beringia during the LGM 16-14 kya peopling of the Americas just after the LGM

The archaeological community is in general agreement that the ancestors of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas of historical record entered the Americas at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), shortly after 20,000 years ago, with ascertained archaeological presence shortly after 16,000 years ago.

There remain uncertainties regarding the precise dating of individual sites and regarding conclusions drawn from population genetics

studies of contemporary Native Americans. It is also an open question

whether this post-LGM migration represented the first peopling of the

Americas, or whether there had been an earlier, pre-LGM migration which

had reached South America as early as 40,000 years ago.

Chronology

In the early 21st century, the models of the chronology of migration are divided into two general approaches.

The first is the short chronology theory, that the first migration occurred after the Last Glacial Maximum, which went into decline after about 19,000 years ago, and was then followed by successive waves of immigrants.

The second theory is the long chronology theory, which proposes that the first group of people entered the Americas at a much earlier date, possibly before 40,000 years ago, followed by a much later second wave of immigrants.

The Clovis First theory,

which dominated thinking on New World anthropology for much of the 20th

century, was challenged by the secure dating of archaeosites in the

Americas

to before 13kya in the 2000s.

The "short chronology" scenario, in the light of this, refers to a

peopling of the Americas shortly after 19,000 years ago, while the "long

chronology" scenario permits pre-LGM presence, by around 40 kya.

The Buttermilk Creek Complex

in Texas, 40 miles northwest of Austin, is seen as one of the oldest

confirmed sites in the Americas, dating to 15,500 years ago. It features

the oldest spear points in the Americas.

Archaeological evidence of pre-Clovis people points to the South Carolina Topper Site being 16,000 years old, at a time when the glacial maximum would have theoretically allowed for lower coastlines, but intense glaciation

would render the terrain virtually impassable. The results of a

multiple-author study by Danish, Canadian, and American scientists

published in Nature

in 2016 revealed that "the first Americans, whether Clovis or earlier

groups in unglaciated North America before 12.6 cal. kyr BP", are

"unlikely" to "have travelled to North America from Siberia via the

Bering land bridge

"via a corridor that opened up between the melting ice sheets in what

is now Alberta and B.C. about 13,000 years ago" as many anthropologists

had argued for decades. The lead author, Mikkel Pedersen – a PhD student from University of Copenhagen

– explained, "The ice-free corridor was long considered the principal

entry route for the first Americans ... Our results reveal that it

simply opened up too late for that to have been possible."

The scientists argued that by 10,000 years ago, the ice-free corridor

in what is now Alberta and B.C "was gradually taken over by a boreal

forest dominated by spruce and pine trees" and that "Clovis people

likely came from the south, not the north, perhaps following wild

animals such as bison.".

One proposed theory to account for the peopling of America is their

arrival by boat. This hypothesis would require more excavation of

coastal sites particularly in British Columbia and Alaska, many of which

would have been submerged due to the rising sea level following the Last Glacial Maximum.

Evidence for pre-LGM human presence

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of maternal (mtDNA) gene-flow in and out of Beringia (long chronology, single source model).

Map

of Beringia showing the exposed seafloor and glaciation at 40 kya and

16 kya. The green arrow indicates the "interior migration" model along

an ice-free corridor separating the major continental ice sheets, the

red arrow indicates the "coastal migration" model, both leading to a "rapid colonization" of the Americas after c. 16 kya.

Pre-Last Glacial Maximum migration across Beringia into the Americas

has been proposed to explain purported pre-LGM ages of archaeosites in

the Americas such as Bluefish Caves and Old Crow Flats in the Yukon Territory, and Meadowcroft Rock Shelter in Pennsylvania.

At the Old Crow Flats, mammoth bones have been found that are

broken in distinctive ways indicating human butchery. The radiocarbon

dates on these vary between 25 000 and 40 000 years BP."

Also, stone microflakes have been found in the area indicating tool production.

Previously, the interpretations of butcher marks and the geologic

association of bones at the Bluefish Cave and Old Crow Flats sites, and

the related Bonnet Plume site, have been called into question.

Yet newer research is answering some of these objections, and providing

more support for the original research of the Canadian archaeologist

Jacques Cinq-Mars, first published in 1979.

Pre-LGM human presence in South America rests partly on the chronology of the controversial Pedra Furada rock shelter in Piauí, Brazil. A 2003 study dated evidence for the controlled use of fire to before 40 kya. Additional evidence has been adduced from the morphology of Luzia Woman fossil, which was described as Australoid.

This interpretation was challenged in a 2003 review which concluded the

features in question could also have arisen by genetic drift.

The ages of the earliest positively identified artifacts at the

Meadowcroft site are constrained by a compiled age estimate from 14C in the range of 12k–15k 14C years BP (13.8k–18.5k cal years BP). The units cal BP

mean "calibrated years before the present" or "calendar years before

the present", indicating that the dates were estimated using radiocarbon dating, and the k after the number means thousands.

The Meadowcroft Rockshelter site and the Monte Verde site in southern Chile, with a date of 14.8k cal years BP, are the archaeosites in the Americas with the oldest dates that have gained broad acceptance.

Stones described as probable tools, hammerstones and anvils, have been found in southern California, at the Cerutti Mastodon site, that are associated with a mastodon

skeleton which appeared to have been processed by humans. The mastodon

skeleton was dated by thorium-230/uranium radiometric analysis, using

diffusion–adsorption–decay dating models, to 130.7 ± 9.4 thousand years

ago. No human bones were found, and the claims of tools and bone processing have been described as "not plausible".

The Yana River Rhino Horn site (RHS) has dated human occupation of eastern Arctic Siberia to 27k 14C years BP (31.3k cal years BP).

That date has been interpreted by some as evidence that migration into

Beringia was imminent, lending credence to occupation of Beringia during

the LGM. However, the Yana RHS date is from the beginning of the cooling period that led into the LGM.

But, a compilation of archaeosite dates throughout eastern Siberia

suggest that the cooling period caused a retreat of humans southwards.

Pre-LGM lithic evidence in Siberia indicate a settled lifestyle that

was based on local resources, while post-LGM lithic evidence indicate a

more migratory lifestyle.

The oldest archaeosite on the Alaskan side of Beringia date to 12k 14C years BP (14k cal years BP).

It is possible that a small founder population had entered Beringia

before that time. However, archaeosites that date closer to the Last

Glacial Maximum on either the Siberian or the Alaskan side of Beringia

are lacking.

Genomic age estimates

Studies of Amerindian genetics

have used high resolution analytical techniques applied to DNA samples

from modern Native Americans and Asian populations regarded as their

source populations to reconstruct the development of human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups (yDNA haplogroups) and human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups (mtDNA haplogroups) characteristic of Native American populations.

Models of molecular evolution rates were used to estimate the ages at

which Native American DNA lineages branched off from their parent

lineages in Asia and to deduce the ages of demographic events.

One model (Tammetal 2007) based on Native American mtDNA Haplotypes

(Figure 2) proposes that migration into Beringia

occurred between 30k and 25k cal years BP, with migration into the

Americas occurring around 10k to 15k years after isolation of the small founding population.

Another model (Kitchen et al. 2008) proposes that migration into

Beringia occurred approximately 36k cal years BP, followed by 20k years

of isolation in Beringia.

A third model (Nomatto et al. 2009) proposes that migration into

Beringia occurred between 40k and 30k cal years BP, with a pre-LGM

migration into the Americas followed by isolation of the northern

population following closure of the ice-free corridor.

Evidence of Australo-Melanesians admixture in Amazonian populations was found by Skoglund and Reich (2016).

A study of the diversification of mtDNA Haplogroups C and D from

southern Siberia and eastern Asia, respectively, suggests that the

parent lineage (Subhaplogroup D4h) of Subhaplogroup D4h3, a lineage

found among Native Americans and Han Chinese, emerged around 20k cal years BP, constraining the emergence of D4h3 to post-LGM. Age estimates based on Y-chromosome micro-satellite diversity place origin of the American Haplogroup Q1a3a (Y-DNA) at around 10k to 15k cal years BP.

Greater consistency of DNA molecular evolution rate models with each

other and with archaeological data may be gained by the use of dated

fossil DNA to calibrate molecular evolution rates.

Source populations

There

is general agreement among anthropologists that the source populations

for the migration into the Americas originated from an area somewhere

east of the Yenisei River.

The common occurrence of the mtDNA Haplogroups A, B, C, and D among

eastern Asian and Native American populations has long been recognized,

along with the presence of Haplogroup X. As a whole, the greatest frequency of the four Native American associated haplogroups occurs in the Altai-Baikal region of southern Siberia.

Some subclades of C and D closer to the Native American subclades occur

among Mongolian, Amur, Japanese, Korean, and Ainu populations.

Human genomic models

The development of high-resolution genomic analysis has provided

opportunities to further define Native American subclades and narrow the

range of Asian subclades that may be parent or sister subclades. For

example, the broad geographic range of Haplogroup X has been interpreted

as allowing the possibility of a western Eurasian, or even a European

source population for Native Americans, as in the Solutrean hypothesis, or suggesting a pre-Last Glacial Maximum migration into the Americas.

The analysis of an ancient variant of Haplogroup X among aboriginals of

the Altai region indicates common ancestry with the European strain

rather than descent from the European strain.

Further division of X subclades has allowed identification of

Subhaplogroup X2a, which is regarded as specific to Native Americans.

With further definition of subclades related to Native American

populations, the requirements for sampling Asian populations to find the

most closely related subclades grow more specific. Subhaplogroups D1

and D4h3 have been regarded as Native American specific based on their

absence among a large sampling of populations regarded as potential

descendants of source populations, over a wide area of Asia. Among the 3764 samples, the Sakhalin – lower Amur region was represented by 61 Oroks. In another study, Subhaplogroup D1a has been identified among the Ulchis of the lower Amur River region(4 among 87 sampled, or 4.6%), along with Subhaplogroup C1a (1 among 87, or 1.1%). Subhaplogroup C1a is regarded as a close sister clade of the Native American Subhaplogroup C1b. Subhaplogroup D1a has also been found among ancient Jōmon skeletons from Hokkaido The modern Ainu are regarded as descendants of the Jōmon.

The occurrence of the Subhaplogroups D1a and C1a in the lower Amur

region suggests a source population from that region distinct from the

Altai-Baikal source populations, where sampling did not reveal those two

particular subclades. The conclusions regarding Subhaplogroup D1 indicating potential source populations in the lower Amur and Hokkaido areas stand in contrast to the single-source migration model.

Subhaplogroup D4h3 has been identified among Han Chinese.

Subhaplogroup D4h3 from China does not have the same geographic

implication as Subhaplotype D1a from Amur-Hokkaido, so its implications

for source models are more speculative. Its parent lineage, Subhaplotype

D4h, is believed to have emerged in east Asia, rather than Siberia,

around 20k cal years BP. Subhaplogroup D4h2, a sister clade of D4h3, has also been found among Jōmon skeletons from Hokkaido. D4h3 has a coastal trace in the Americas.

The contrast between the genetic profiles of the Hokkaido Jōmon

skeletons and the modern Ainu illustrates another uncertainty in source

models derived from modern DNA samples:

However, probably due to the small sample size or close consanguinity among the members of the site, the frequencies of the haplogroups in Funadomari skeletons were quite different from any modern populations, including Hokkaido Ainu, who have been regarded as the direct descendant of the Hokkaido Jomon people.

The descendants of source

populations with the closest relationship to the genetic profile from

the time when differentiation occurred are not obvious. Source

population models can be expected to become more robust as more results

are compiled, the heritage of modern proxy candidates becomes better

understood, and fossil DNA in the regions of interest is found and

considered.

HTLV-1 genomics

The Human T cell Lymphotrophic Virus 1 (HTLV-1)

is a virus transmitted through exchange of bodily fluids and from

mother to child through breast milk. The mother-to-child transmission

mimics a hereditary trait, although such transmission from maternal

carriers is less than 100%.

The HTLV virus genome has been mapped, allowing identification of four

major strains and analysis of their antiquity through mutations. The

highest geographic concentrations of the strain HLTV-1 are in

sub-Saharan Africa and Japan. In Japan, it occurs in its highest concentration on Kyushu. It is also present among African descendants and native populations in the Caribbean region and South America. It is rare in Central America and North America. Its distribution in the Americas has been regarded as due to importation with the slave trade.

The Ainu have developed antibodies to HTLV-1, indicating its endemicity to the Ainu and its antiquity in Japan.

A subtype "A" has been defined and identified among the Japanese

(including Ainu), and among Caribbean and South American isolates. A subtype "B" has been identified in Japan and India. In 1995, Native Americans in coastal British Columbia were found to have both subtypes A and B. Bone marrow specimens from an Andean mummy about 1500 years old were reported to have shown the presence of the A subtype.

The finding ignited controversy, with contention that the sample DNA

was insufficiently complete for the conclusion and that the result

reflected modern contamination.

However, a re-analysis indicated that the DNA sequences were consistent

with, but not definitely from, the "cosmopolitan clade" (subtype A).

The presence of subtypes A and B in the Americas is suggestive of a

Native American source population related to the Ainu ancestors, the

Jōmon.

Physical anthropology

Paleoamerican skeletons in the Americas such as Kennewick Man (Washington State), Hoya Negro skeleton (Yucatán), Luzia Woman and other skulls from the Lagoa Santa site (Brazil), Buhl Woman (Idaho), Peñon Woman III, two skulls from the Tlapacoya site (Mexico City), and 33 skulls from Baja California

have exhibited craniofacial traits distinct from most modern Native

Americans, leading physical anthropologists to the opinion that some

Paleoamericans were of an Australoid rather than Siberian origin. The most basic measured distinguishing trait is the dolichocephaly of the skull. Some modern isolates such as the Pericúes of Baja California and the Fuegians of Tierra del Fuego exhibit that same morphological trait. Other anthropologists advocate an alternative hypothesis that evolution of an original Beringian phenotype

gave rise to a distinct morphology that was similar in all known

Paleoamerican skulls, followed by later convergence towards the modern

Native American phenotype.

Resolution of the issue awaits the identification of a Beringian

phenotype among paleoamerican skulls or evidence of a genetic clustering

among examples of the Australoid phenotype.

A report published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology

in January 2015 reviewed craniofacial variation focussing on

differences between early and late Native Americans and explanations for

these based on either skull morphology or molecular genetics. Arguments

based on molecular genetics have in the main, according to the authors,

accepted a single migration from Asia with a probable pause in

Berengia, plus later bi-directional gene flow. Studies focussing on

craniofacial morphology have argued that Paleoamerican remains have

"been described as much closer to African and Australo-Melanesians

populations than to the modern series of Native Americans", suggesting

two entries into the Americas, an early one occurring before a

distinctive East Asian morphology developed (referred to in the paper as

the "Two Components Model". A third model, the "Recurrent Gene Flow"

[RGF] model, attempts to reconcile the two, arguing that circumarctic

gene flow after the initial migration could account for morphological

changes. It specifically re-evaluates the original report on the Hoya

Negro skeleton which supported the RGF model, the authors disagreed with

the original conclusion which suggested that the skull shape did not

match those of modern Native Americans, arguing that the "skull falls

into a subregion of the morphospace occupied by both Paleoamericans and

some modern Native Americans."

Stemmed points

Stemmed

points are a lithic technology distinct from Beringian and Clovis

types. They have a distribution ranging from coastal east Asia to the

Pacific coast of South America. The emergence of stemmed points has been traced to Korea during the upper Paleolithic.

The origin and distribution of stemmed points have been interpreted as a

cultural marker related to a source population from coastal east Asia.

Migration routes

Interior route

Map showing the approximate location of the ice-free corridor along the Continental Divide, separating the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets. Also indicated are the locations of the Clovis and Folsom Paleo-Indian sites.

Historically, theories about migration into the Americas have

centered on migration from Beringia through the interior of North

America. The discovery of artifacts in association with Pleistocene

faunal remains near Clovis, New Mexico

in the early 1930s required extension of the timeframe for the

settlement of North America to the period during which glaciers were

still extensive. That led to the hypothesis of a migration route between

the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets to explain the early

settlement. The Clovis site was host to a lithic technology

characterized by spear points with an indentation, or flute, where the

point was attached to the shaft. A lithic complex characterized by the Clovis Point

technology was subsequently identified over much of North America and

in South America. The association of Clovis complex technology with late

Pleistocene faunal remains led to the theory that it marked the arrival

of big game hunters that migrated out of Beringia then dispersed

throughout the Americas, otherwise known as the Clovis First theory.

Recent radiocarbon dating of Clovis sites has yielded ages of 11.1k to 10.7k 14C years BP (13k to 12.6k cal years BP), somewhat later than dates derived from older techniques.

The re-evaluation of earlier radiocarbon dates led to the conclusion

that no fewer than 11 of the 22 Clovis sites with radiocarbon dates are

"problematic" and should be disregarded, including the type site

in Clovis, New Mexico. Numerical dating of Clovis sites has allowed

comparison of Clovis dates with dates of other archaeosites throughout

the Americas, and of the opening of the ice-free corridor. Both lead to

significant challenges to the Clovis First theory. The Monte Verde site

of Southern Chile has been dated at 14.8k cal years BP. The Paisley Cave site in eastern Oregon yielded a 14C date of 12.4k years (14.5k cal years) BP, on a coprolite with human DNA and 14C dates of 11.3k-11k (13.2k-12.9k cal years) BP on horizons containing western stemmed points.

Artifact horizons with non-Clovis lithic assemblages and pre-Clovis

ages occur in eastern North America, although the maximum ages tend to

be poorly constrained.

Geological findings on the timing of the ice-free corridor also

challenge the notion that Clovis and pre-Clovis human occupation of the

Americas was a result of migration through that route following the Last Glacial Maximum.

Pre-LGM closing of the corridor may approach 30k cal years BP and

estimates of ice retreat from the corridor are in the range of 12 to 13k

cal years BP.[11][12][13]

Viability of the corridor as a human migration route has been estimated

at 11.5k cal years BP, later than the ages of the Clovis and pre-Clovis

sites. Dated Clovis archaeosites suggest a south-to-north spread of the Clovis culture.

Pre-Last Glacial Maximum migration into the interior has been

proposed to explain pre-Clovis ages for archaeosites in the Americas, although pre-Clovis sites such as Meadowcroft Rock Shelter, Monte Verde, and Paisley Cave have not yielded confirmed pre-LGM ages.

The interior route is consistent with the spread of the Na Dene

language group and Subhaplogroup X2a into the Americas after the

earliest paleoamerican migration.

Pacific coastal route

Pacific models propose that people first reached the Americas via

water travel, following coastlines from northeast Asia into the

Americas. Coastlines are unusually productive environments because they

provide humans with access to a diverse array of plants and animals from

both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. While not exclusive of

land-based migrations, the Pacific 'coastal migration theory' helps

explain how early colonists reached areas extremely distant from the

Bering Strait region, including sites such as Monte Verde in southern Chile and Taima-Taima in western Venezuela. Two cultural components were discovered at Monte Verde near the Pacific coast of Chile. The youngest layer is radiocarbon dated at 12,500 radiocarbon years (~14,000 cal BP)

and has produced the remains of several types of seaweeds collected

from coastal habitats. The older and more controversial component may

date back as far as 33,000 years, but few scholars currently accept this

very early component.

As the chronology of deglaciation in the interior and coastal

regions of North America became better understood, the coastal migration

hypothesis was advanced by Knute Fladmark as an alternative to the

ice-free corridor hypothesis.

Debate on coastal versus interior migration for initial settlement has

centered on evidence for chronology of initial settlement of Beringia, interior North America, the Pacific coast of the Americas, and timing of the opening of coastal versus interior migration routes indicated by geological evidence.

Complicating the debate has been the absence of archaeological data

from the coastal and interior migration routes from the periods when the

initial migration is proposed to have occurred. A recent variation of

the coastal migration hypothesis is the marine migration hypothesis,

which proposes that migrants with boats settled in coastal refugia

during deglaciation of the coast.

The proposed use of boats adds a measure of flexibility to the

chronology of coastal migration, as a continuous ice-free coast (16k-15k

cal years BP) would no longer be required. A coastal east Asian source

population is integral to the marine migration hypothesis.

In 2014, the autosomal DNA of a toddler from Montana, dated at 10.7k 14C years (12.5–12.7 cal years) BP was sequenced. The DNA was taken from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1,

found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. The analysis

yielded identification of the mtDNA as belonging to Subhaplogroup D4h3a,

a rare subclade of D4h3 occurring along the west coast of the Americas,

as well as geneflow related to the Siberian Mal'ta population. The data

indicate that Anzick-1 is from a population directly ancestral to

present South American and Central American Native American populations.

Anzick-1 is less closely related to present North American Native

American populations. D4h3a has been identified as a clade associated

with coastal migration.

The problems associated with finding archaeological evidence for migration during a period of lowered sea level are well known.

Sites related to the first migration are usually submerged, so the

location of such sites is obscured. Certain types of evidence dependent

on organic material, such as radiocarbon dating, may be destroyed by

submergence. Wave action can destroy site structures and scatter

artifacts along a prograding shoreline. Additionally, Pacific coastal

conditions tend to be unstable due to steep unstable terrain,

earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes. Strategies for finding earliest

migration sites include identifying potential sites on submerged

paleoshorelines, seeking sites in areas uplifted either by tectonics or

isostatic rebound, and looking for riverine sites in areas that may have

attracted coastal migrants.

Otherwise, coastal archaeology is dependent on secondary evidence

related to lifestyles and technologies of maritime peoples from sites

similar to those that would be associated with the original migration.

Other coastal models, dealing specifically with the peopling of the Pacific Northwest and California coasts, have been advocated by archaeologists Knut Fladmark, Roy Carlson, James Dixon, Jon Erlandson, Ruth Gruhn, and Daryl Fedje. In a 2007 article in the Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology,

Erlandson and his colleagues proposed a corollary to the coastal

migration theory—the "kelp highway hypothesis"—arguing that productive kelp

forests supporting similar suites of plants and animals would have

existed near the end of the Pleistocene around much of the Pacific Rim

from Japan to Beringia, the Pacific Northwest, and California, as well

as the Andean Coast of South America. Once the coastlines of Alaska and

British Columbia had deglaciated about 16,000 years ago, these kelp

forest (along with estuarine, mangrove, and coral reef) habitats would

have provided an ecologically similar migration corridor, entirely at

sea level, and essentially unobstructed.

A 2016 DNA analysis of plants and animals suggest a coastal route was feasible.

East Asians: Paleoindians of the coast

The boat-builders from Southeast Asia (Austronesian peoples) may have been one of the earliest groups to reach the shores of North America. One theory suggests people in boats followed the coastline from the Kurile Islands to Alaska down the coasts of North and South America as far as Chile. 62 54, 57. The Haida nation on the Queen Charlotte Islands off the coast of British Columbia

may have originated from these early Asian mariners between 25,000 and

12,000 years ago. Early watercraft migration would also explain the

habitation of coastal sites in South America such as Pikimachay Cave in Peru by 20,000 years ago (disputed) and Monte Verde in Chile by 13,000 years ago [6 30; 8 383].

'There was boat use in Japan 20,000 years ago,' says Jon Erlandson, a University of Oregon anthropologist. 'The Kurile Islands (north of Japan) are like stepping stones to Beringia,' the then continuous land bridging the Bering Strait. Migrants, he said, could have then skirted the tidewater glaciers in Canada right on down the coast. [7 64]'

Problems with evaluating coastal migration models

The

coastal migration models provide a different perspective on migration

to the New World, but they are not without their own problems. One such

problem is that global sea levels have risen over 120 metres (390 ft)

since the end of the last glacial period, and this has submerged the

ancient coastlines that maritime people would have followed into the

Americas. Finding sites associated with early coastal migrations is

extremely difficult—and systematic excavation of any sites found in

deeper waters is challenging and expensive. On the other hand, there is

evidence of marine technologies found in the hills of the Channel Islands of California, circa 10,000 BCE.

If there was an early pre-Clovis coastal migration, there is always the

possibility of a "failed colonization". Another problem that arises is

the lack of hard evidence found for a "long chronology" theory. No sites

have yet produced a consistent chronology older than about 12,500

radiocarbon years (~14,500 calendar years), but research has been limited in South America related to the possibility of early coastal migrations.

Y-DNA among South American and Alaskan natives

The micro-satellite

diversity and distribution of a Y lineage specific to South America

suggest that certain Amerindian populations became isolated after the

initial colonization of their regions. The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, but are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA and autosomal DNA (atDNA) mutations. This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations.

!["Maps depicting each phase of the three-step early human migrations for the peopling of the Americas. (A) Gradual population expansion of the Amerind ancestors from their Central East Asian gene pool (blue arrow). (B) Proto-Amerind occupation of Beringia with little to no population growth for ≈20,000 years. (C) Rapid colonization of the New World by a founder group migrating southward through the ice-free, inland corridor between the eastern Laurentide and western Cordilleran Ice Sheets (green arrow) and/or along the Pacific coast (red arrow). In (B), the exposed seafloor is shown at its greatest extent during the last glacial maximum at ≈20–18 kya [25]. In (A) and (C), the exposed seafloor is depicted at ≈40 kya and ≈16 kya, when prehistoric sea levels were comparable. A scaled-down version of Beringia today (60% reduction of A–C) is presented in the lower left corner. This smaller map highlights the Bering Strait that has geographically separated the New World from Asia since ≈11–10 kya."](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d7/Journal.pone.0001596.g004.png/280px-Journal.pone.0001596.g004.png)