A good friend of Socrates, once asked the Oracle at Delphi “is anyone wiser than Socrates?”

The Oracle answered “No one.”

This

greatly puzzled Socrates, since he claimed to possess no secret

information or wise insight. As far as Socrates was concerned, he was

the most ignorant man in the land.

Socrates

was determined to prove the Oracle wrong. He toured Athens up and down,

talking to its wisest and most capable people, trying to find someone

wiser than he was.

What

he found was that poets didn’t know why their words moved people,

craftsmen only knew how to master their trade and not much else, and

politicians thought they were wise but didn’t have the knowledge to back

it up.

What Socrates discovered was that none of these people

knew anything, but they all thought they did. Socrates concluded he was

wiser than them, because he at least knew that he knew nothing.

This

at least is the story of the phrase. It’s been almost 2500 years since

its longer form was initially written. In that time, it has caught a

life of its own and now has many different interpretations.

I know that I know nothing – 5 interpretations

I know that I know nothing, because I can’t trust my brain

One interpretations of the phrase asks if you can be 100% certain if a piece of information is true.

Imagine this question: “Is the Sun real?”

If

it’s day time, the answer is immediately obvious because you can simply

point your hand at the Sun and say: “Yes, of course the Sun is real.

There it is.”

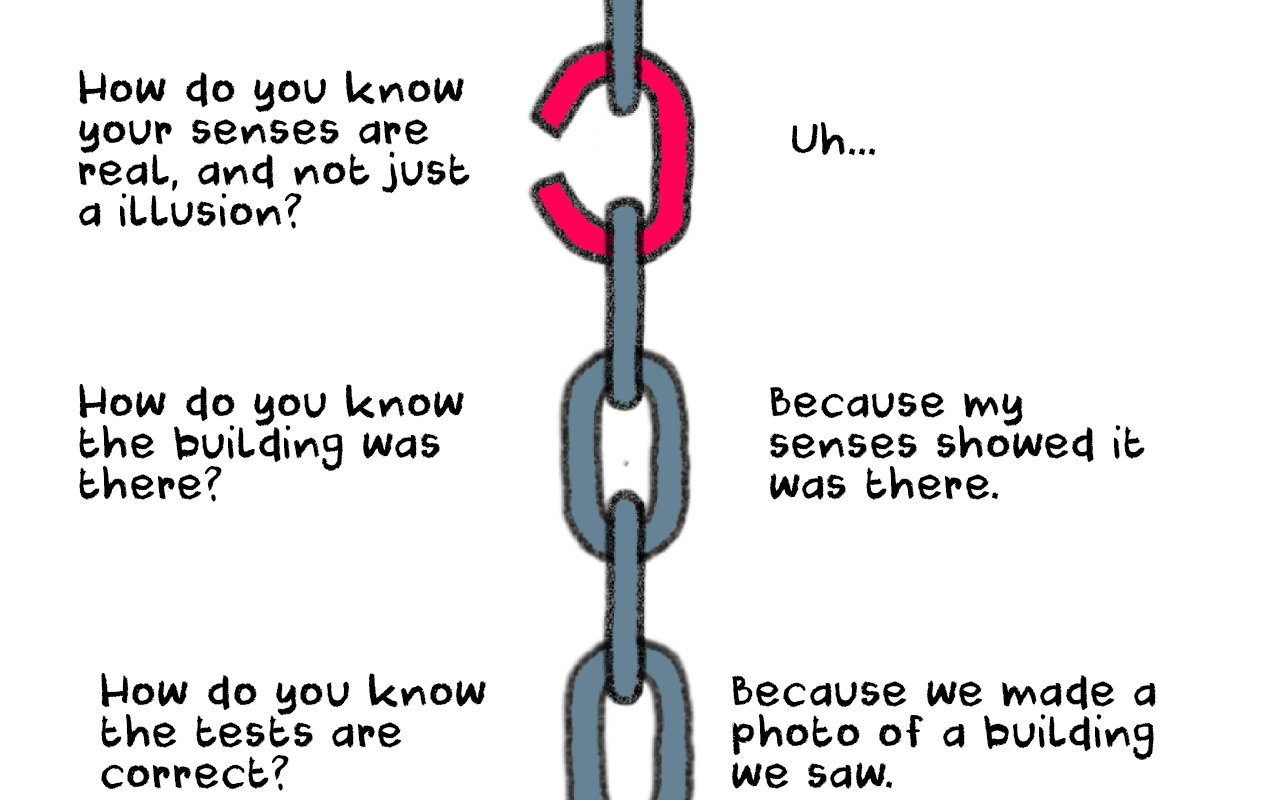

But then, you will fall into something called the infinite regress problem. This means every proof you have, must be backed up by another proof, and that proof too must be backed up by another one.

As

you go down the infinite regress, you will reach a point where you have

no proof to back up a statement. Because that one argument can’t be

proven, it then crashes all of the other statements made up to it.

French philosopher Rene Descartes went so far with the infinite regression, that he imagined the whole world was just an elaborate illusion created by an Evil Demon that wanted to trick him.

As

the Evil Demon scenario shows, the infinite regression will often go so

far down it will challenge whether any of the information entering your

brain is real or not.

Thus, if all the information you’re receiving through the senses is an illusion, then by extension you know nothing.

Counterarguments: Descartes came up with the phrase “I think, therefore I am”.

This puts a stop to the infinite regress since it’s impossible to doubt

your own existence because simply by thinking, you prove that your

consciousness exists.

Another philosophical counter argument is that some statements do not require proof in order to be called true. These are called self-evident truths, and include statements such as:

- 2+2 = 4

- A room that contains a bed is automatically bigger than the bed.

- A square contains 4 sides.

These self-evident truths act as foundations stones that allow knowledge to be built upon.

I know that I know nothing, because the physical world isn’t real

Socrates never left behind any written texts (mostly because he hated writing, saying it would damage our memory). All of the things we know about Socrates comes mostly from Plato, and to a lesser extent, Xenophon.

However,

Plato wrote his philosophy in dialogue form and always used Socrates as

the voice for his own ideas. Because of this, it’s almost impossible to

separate the true Socrates from Plato.

One

interesting interpretation of “I know that I know nothing”, is that the

phrase could actually belong to Plato, alluding to one of his ideas: the theory of forms.

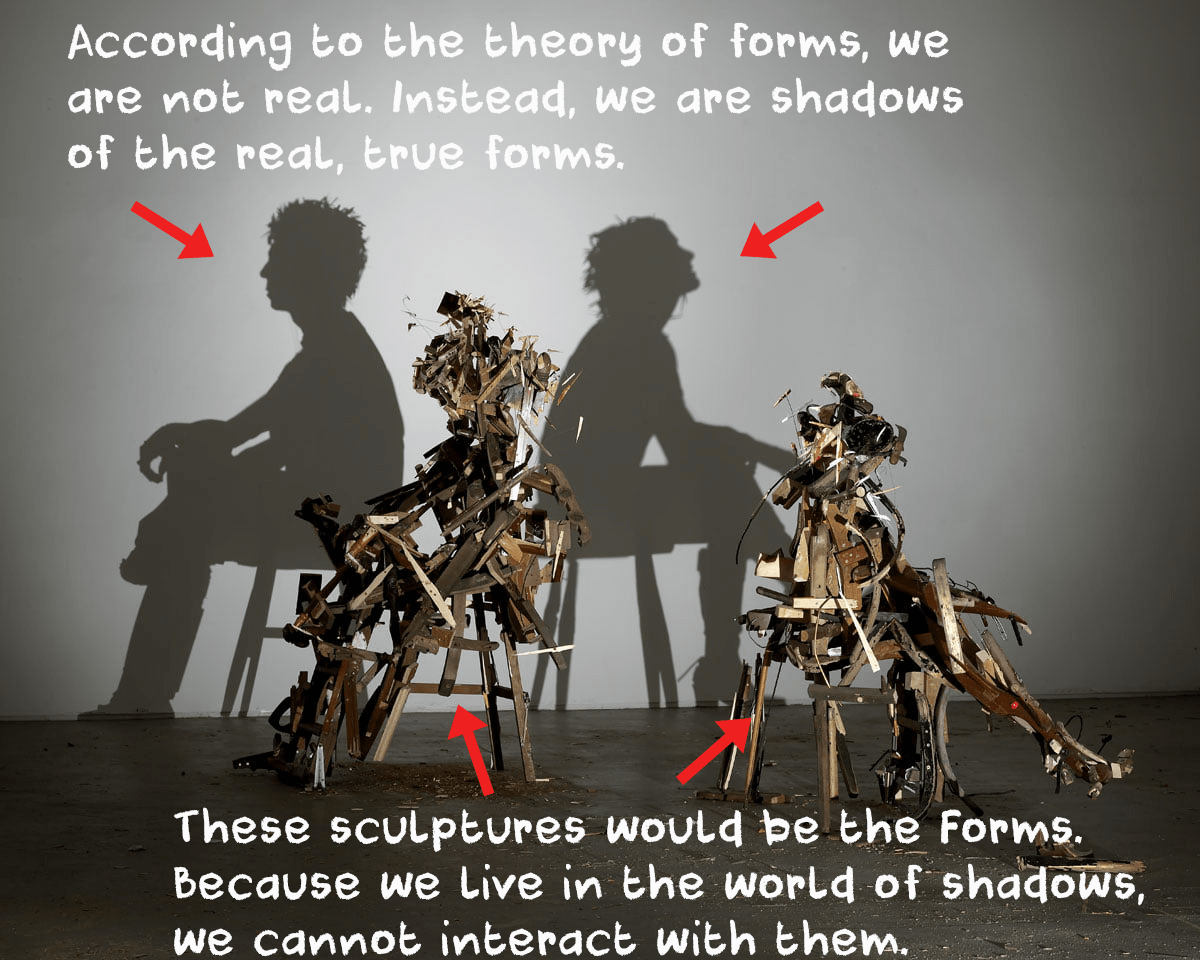

According

to theory of forms, the physical world we live in, the one where you

can read this article on a monitor or hold a glass of water, is actually

just a shadow.

The real world is that of “ideas” or “forms”.

These are non-physical essences that exist outside of our physical

world. Everything in our dimension is just an imitation, or projection

of these forms and ideas.

Another

way to think about the forms, is to compare something that exists in

the real world vs. its ideal version. For instance, imagine the perfect

apple, and then compare it to real world apples you’ve seen or eaten.

The

perfect apple (in terms of weight, crunchiness, taste, color, texture,

smell etc.) only exists in the realm of forms, and every apple you’ve

seen in real life is just a shadow, an imitation of the perfect one.

That

being said, the theory of forms does have some major limitations. One

of them is that a human living in the physical / shadow realm, you can

never know how an ideal form looks like. The best you can do is to just

think what a perfect apple, human, character, marriage etc. look like,

and try to stick to that ideal as much as possible.

You’ll never

know for sure what the ideal looks like. In this sense, “I know I know

nothing” can mean “I only know the physical realm, but I know nothing

about the real of forms”.

I know that I know nothing, because information can be uncertain

A

more straightforward interpretation is that you can never be sure if a

piece of information is correct. Viewed from this perspective, “I know

that I know nothing” becomes a motto that stops you from making hasty

judgement based on incomplete or potentially false information.

This

interpretation is also connected with the historical context in which

Socrates (or Plato) uttered the phrase. At the time, Pyrrhonism was a

philosophical school that claimed you cannot discover the truth for

anything (except the self-evident such as 2+2=4).

From the Pyrrhonist point of view,

you cannot say for sure if a statement is correct or false because

there will always be arguments for and against that will cancel each

other out.

For instance, imagine the color green.

A Pyrrhonist would argue that you cannot be sure this is the color green because:

- Animals might perceive this color differently.

- Other people might perceive the color differently because of different lighting, color blindness etc.

A non-philosopher would just say “it’s green dammit, what more do you need?” and close the problem.

What

makes Pyrrhonists different is that instead of saying “yes this is a

color, and that color is green”, they will simply say “yes, this is a

color, but I’m not sure which so I’d rather not say”.

For

Pyrrhonists however, such a position was not just a philosophical

exercise. They extended this way of thinking to their entire lives so it

became a mindset called epoché,

translated as suspension of judgement. This suspension of judgement

then led to the mental state of ataraxia, often translated as

tranquility.

From the Pyrrhonist point of view, people cannot

achieve happiness because their minds are in a state of conflict by

having to come to conclusions in the face of contradictory arguments.

As

a result, Pyrrhonists chose to suspend their judgement on all problems

that were not self-evident, hoping that thus they will achieve true

happiness.

Ultimately, from the Pyrrhonist perspective, “I know that I know nothing” can mean “truth cannot be discovered”.

I know that I know nothing – the paradox

A

more conventional approach to the phrase is to simply view it as a

self-referential paradox. The most well-known self-referential paradox

is the phrase “this sentence is a lie”.

These pair of drawing hands by M.C. Escher self-reference each other

When

it comes to science and knowledge, paradoxes function as indications

that a logical argument is flawed, or that our way of thinking will

produce bad results.

A more interesting overview of self-referencing paradoxes is the book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid

by Douglas Hofstader. This book explores how meaningless elements,

(such as carbon, hydrogen etc.) form systems, and how these systems can

then become self-aware through a process of self-reference.

I know that I know nothing – a motto of humility

Socrates lived in a world that had accumulated very little knowledge.

As

a fun fact, Aristotle (who was born some 15 years after Socrates died),

was said to be the last man on Earth to have known every ounce of

knowledge available at the time.

From the perspective of Socrates,

any knowledge or information he did have was likely to be insignificant

(or even completely false) compared to how much was left to be

discovered.

From

such a position, it’s easier to say “I know that I know nothing” rather

than the more technical truth: “I only know the tiniest bit of

knowledge, and even that is probably incorrect”.

The same

principle still applies to us, if we compare ourselves to humans living

200-300 years in the future. And unlike Socrates, we have a giant wealth

of information to dive in whenever we want.