Physical cosmology is a branch of cosmology concerned with the studies of the largest-scale structures and dynamics of the universe and with fundamental questions about its origin, structure, evolution, and ultimate fate. Cosmology as a science originated with the Copernican principle, which implies that celestial bodies obey identical physical laws to those on Earth, and Newtonian mechanics, which first allowed those physical laws to be understood. Physical cosmology, as it is now understood, began with the development in 1915 of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, followed by major observational discoveries in the 1920s: first, Edwin Hubble discovered that the universe contains a huge number of external galaxies beyond the Milky Way; then, work by Vesto Slipher and others showed that the universe is expanding. These advances made it possible to speculate about the origin of the universe, and allowed the establishment of the Big Bang theory, by Georges Lemaître, as the leading cosmological model. A few researchers still advocate a handful of alternative cosmologies; however, most cosmologists agree that the Big Bang theory explains the observations better.

Dramatic advances in observational cosmology since the 1990s, including the cosmic microwave background, distant supernovae and galaxy redshift surveys, have led to the development of a standard model of cosmology. This model requires the universe to contain large amounts of dark matter and dark energy whose nature is currently not well understood, but the model gives detailed predictions that are in excellent agreement with many diverse observations.

Cosmology draws heavily on the work of many disparate areas of research in theoretical and applied physics. Areas relevant to cosmology include particle physics experiments and theory, theoretical and observational astrophysics, general relativity, quantum mechanics, and plasma physics.

Subject history

Modern cosmology developed along tandem tracks of theory and observation. In 1916, Albert Einstein published his theory of general relativity, which provided a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time. At the time, Einstein believed in a static universe, but found that his original formulation of the theory did not permit it. This is because masses distributed throughout the universe gravitationally attract, and move toward each other over time.

However, he realized that his equations permitted the introduction of a

constant term which could counteract the attractive force of gravity on

the cosmic scale. Einstein published his first paper on relativistic

cosmology in 1917, in which he added this cosmological constant to his field equations in order to force them to model a static universe.

The Einstein model describes a static universe; space is finite and

unbounded (analogous to the surface of a sphere, which has a finite area

but no edges). However, this so-called Einstein model is unstable to

small perturbations—it will eventually start to expand or contract.

It was later realized that Einstein's model was just one of a larger

set of possibilities, all of which were consistent with general

relativity and the cosmological principle. The cosmological solutions of

general relativity were found by Alexander Friedmann in the early 1920s. His equations describe the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker universe, which may expand or contract, and whose geometry may be open, flat, or closed.

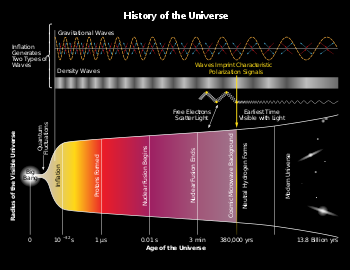

History of the Universe – gravitational waves are hypothesized to arise from cosmic inflation, a faster-than-light expansion just after the Big Bang

In the 1910s, Vesto Slipher (and later Carl Wilhelm Wirtz) interpreted the red shift of spiral nebulae as a Doppler shift that indicated they were receding from Earth.

However, it is difficult to determine the distance to astronomical

objects. One way is to compare the physical size of an object to its angular size, but a physical size must be assumed to do this. Another method is to measure the brightness of an object and assume an intrinsic luminosity, from which the distance may be determined using the inverse square law. Due to the difficulty of using these methods, they did not realize that the nebulae were actually galaxies outside our own Milky Way, nor did they speculate about the cosmological implications. In 1927, the Belgian Roman Catholic priest Georges Lemaître

independently derived the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker equations

and proposed, on the basis of the recession of spiral nebulae, that the

universe began with the "explosion" of a "primeval atom"—which was later called the Big Bang. In 1929, Edwin Hubble

provided an observational basis for Lemaître's theory. Hubble showed

that the spiral nebulae were galaxies by determining their distances

using measurements of the brightness of Cepheid variable

stars. He discovered a relationship between the redshift of a galaxy

and its distance. He interpreted this as evidence that the galaxies are

receding from Earth in every direction at speeds proportional to their

distance. This fact is now known as Hubble's law,

though the numerical factor Hubble found relating recessional velocity

and distance was off by a factor of ten, due to not knowing about the

types of Cepheid variables.

Given the cosmological principle,

Hubble's law suggested that the universe was expanding. Two primary

explanations were proposed for the expansion. One was Lemaître's Big

Bang theory, advocated and developed by George Gamow. The other

explanation was Fred Hoyle's steady state model

in which new matter is created as the galaxies move away from each

other. In this model, the universe is roughly the same at any point in

time.

For a number of years, support for these theories was evenly

divided. However, the observational evidence began to support the idea

that the universe evolved from a hot dense state. The discovery of the

cosmic microwave background in 1965 lent strong support to the Big Bang

model, and since the precise measurements of the cosmic microwave background by the Cosmic Background Explorer

in the early 1990s, few cosmologists have seriously proposed other

theories of the origin and evolution of the cosmos. One consequence of

this is that in standard general relativity, the universe began with a singularity, as demonstrated by Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking in the 1960s.

An alternative view to extend the Big Bang model, suggesting the

universe had no beginning or singularity and the age of the universe is

infinite, has been presented.

Energy of the cosmos

The lightest chemical elements, primarily hydrogen and helium, were created during the Big Bang through the process of nucleosynthesis. In a sequence of stellar nucleosynthesis reactions, smaller atomic nuclei are then combined into larger atomic nuclei, ultimately forming stable iron group elements such as iron and nickel, which have the highest nuclear binding energies. The net process results in a later energy release, meaning subsequent to the Big Bang. Such reactions of nuclear particles can lead to sudden energy releases from cataclysmic variable stars such as novae. Gravitational collapse of matter into black holes also powers the most energetic processes, generally seen in the nuclear regions of galaxies, forming quasars and active galaxies.

Cosmologists cannot explain all cosmic phenomena exactly, such as those related to the accelerating expansion of the universe, using conventional forms of energy. Instead, cosmologists propose a new form of energy called dark energy that permeates all space. One hypothesis is that dark energy is just the vacuum energy, a component of empty space that is associated with the virtual particles that exist due to the uncertainty principle.

There is no clear way to define the total energy in the universe using the most widely accepted theory of gravity, general relativity. Therefore, it remains controversial whether the total energy is conserved in an expanding universe. For instance, each photon that travels through intergalactic space loses energy due to the redshift

effect. This energy is not obviously transferred to any other system,

so seems to be permanently lost. On the other hand, some cosmologists

insist that energy is conserved in some sense; this follows the law of conservation of energy.

Thermodynamics of the universe is a field of study that explores which form of energy dominates the cosmos – relativistic particles which are referred to as radiation, or non-relativistic particles referred to as matter. Relativistic particles are particles whose rest mass is zero or negligible compared to their kinetic energy,

and so move at the speed of light or very close to it; non-relativistic

particles have much higher rest mass than their energy and so move much

slower than the speed of light.

As the universe expands, both matter and radiation in it become diluted. However, the energy densities

of radiation and matter dilute at different rates. As a particular

volume expands, mass energy density is changed only by the increase in

volume, but the energy density of radiation is changed both by the

increase in volume and by the increase in the wavelength of the photons

that make it up. Thus the energy of radiation becomes a smaller part of

the universe's total energy than that of matter as it expands. The very

early universe is said to have been 'radiation dominated' and radiation

controlled the deceleration of expansion. Later, as the average energy

per photon becomes roughly 10 eV

and lower, matter dictates the rate of deceleration and the universe is

said to be 'matter dominated'. The intermediate case is not treated

well analytically. As the expansion of the universe continues, matter dilutes even further and the cosmological constant becomes dominant, leading to an acceleration in the universe's expansion.

History of the universe

The history of the universe is a central issue in cosmology. The

history of the universe is divided into different periods called epochs,

according to the dominant forces and processes in each period. The

standard cosmological model is known as the Lambda-CDM model.

Equations of motion

Within the standard cosmological model, the equations of motion governing the universe as a whole are derived from general relativity with a small, positive cosmological constant.

The solution is an expanding universe; due to this expansion, the

radiation and matter in the universe cool down and become diluted. At

first, the expansion is slowed down by gravitation attracting the radiation

and matter in the universe. However, as these become diluted, the

cosmological constant becomes more dominant and the expansion of the

universe starts to accelerate rather than decelerate. In our universe

this happened billions of years ago.

Particle physics in cosmology

During the earliest moments of the universe the average energy density was very high, making knowledge of particle physics critical to understanding this environment. Hence, scattering processes and decay of unstable elementary particles are important for cosmological models of this period.

As a rule of thumb, a scattering or a decay process is

cosmologically important in a certain epoch if the time scale describing

that process is smaller than, or comparable to, the time scale of the

expansion of the universe. The time scale that describes the expansion of the universe is with being the Hubble parameter, which varies with time. The expansion timescale is roughly equal to the age of the universe at each point in time.

Timeline of the Big Bang

Observations suggest that the universe began around 13.8 billion years ago.

Since then, the evolution of the universe has passed through three

phases. The very early universe, which is still poorly understood, was

the split second in which the universe was so hot that particles had energies higher than those currently accessible in particle accelerators

on Earth. Therefore, while the basic features of this epoch have been

worked out in the Big Bang theory, the details are largely based on

educated guesses.

Following this, in the early universe, the evolution of the universe

proceeded according to known high energy physics.

This is when the first protons, electrons and neutrons formed, then

nuclei and finally atoms. With the formation of neutral hydrogen, the cosmic microwave background was emitted. Finally, the epoch of structure formation began, when matter started to aggregate into the first stars and quasars, and ultimately galaxies, clusters of galaxies and superclusters formed. The future of the universe is not yet firmly known, but according to the ΛCDM model it will continue expanding forever.

Areas of study

Below,

some of the most active areas of inquiry in cosmology are described, in

roughly chronological order. This does not include all of the Big Bang

cosmology, which is presented in Timeline of the Big Bang.

Very early universe

The early, hot universe appears to be well explained by the Big Bang from roughly 10−33 seconds onwards, but there are several problems. One is that there is no compelling reason, using current particle physics, for the universe to be flat, homogeneous, and isotropic (see the cosmological principle). Moreover, grand unified theories of particle physics suggest that there should be magnetic monopoles in the universe, which have not been found. These problems are resolved by a brief period of cosmic inflation, which drives the universe to flatness, smooths out anisotropies and inhomogeneities to the observed level, and exponentially dilutes the monopoles.

The physical model behind cosmic inflation is extremely simple, but it

has not yet been confirmed by particle physics, and there are difficult

problems reconciling inflation and quantum field theory. Some cosmologists think that string theory and brane cosmology will provide an alternative to inflation.

Another major problem in cosmology is what caused the universe to contain far more matter than antimatter.

Cosmologists can observationally deduce that the universe is not split

into regions of matter and antimatter. If it were, there would be X-rays and gamma rays produced as a result of annihilation,

but this is not observed. Therefore, some process in the early universe

must have created a small excess of matter over antimatter, and this

(currently not understood) process is called baryogenesis. Three required conditions for baryogenesis were derived by Andrei Sakharov in 1967, and requires a violation of the particle physics symmetry, called CP-symmetry, between matter and antimatter.

However, particle accelerators measure too small a violation of

CP-symmetry to account for the baryon asymmetry. Cosmologists and

particle physicists look for additional violations of the CP-symmetry in

the early universe that might account for the baryon asymmetry.

Both the problems of baryogenesis and cosmic inflation are very

closely related to particle physics, and their resolution might come

from high energy theory and experiment, rather than through observations of the universe.

Big Bang Theory

Big Bang nucleosynthesis is the theory of the formation of the

elements in the early universe. It finished when the universe was about

three minutes old and its temperature dropped below that at which nuclear fusion

could occur. Big Bang nucleosynthesis had a brief period during which

it could operate, so only the very lightest elements were produced.

Starting from hydrogen ions (protons), it principally produced deuterium, helium-4, and lithium. Other elements were produced in only trace abundances. The basic theory of nucleosynthesis was developed in 1948 by George Gamow, Ralph Asher Alpher, and Robert Herman.

It was used for many years as a probe of physics at the time of the Big

Bang, as the theory of Big Bang nucleosynthesis connects the abundances

of primordial light elements with the features of the early universe. Specifically, it can be used to test the equivalence principle, to probe dark matter, and test neutrino physics. Some cosmologists have proposed that Big Bang nucleosynthesis suggests there is a fourth "sterile" species of neutrino.

Standard model of Big Bang cosmology

The ΛCDM (Lambda cold dark matter) or Lambda-CDM model is a parametrization of the Big Bang cosmological model in which the universe contains a cosmological constant, denoted by Lambda (Greek Λ), associated with dark energy, and cold dark matter (abbreviated CDM). It is frequently referred to as the standard model of Big Bang cosmology.

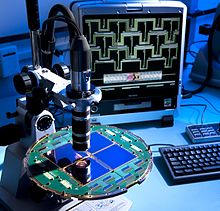

Cosmic microwave background

Evidence of gravitational waves in the infant universe may have been uncovered by the microscopic examination of the focal plane of the BICEP2 radio telescope.

The cosmic microwave background is radiation left over from decoupling after the epoch of recombination when neutral atoms first formed. At this point, radiation produced in the Big Bang stopped Thomson scattering from charged ions. The radiation, first observed in 1965 by Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson, has a perfect thermal black-body spectrum. It has a temperature of 2.7 kelvins today and is isotropic to one part in 105. Cosmological perturbation theory,

which describes the evolution of slight inhomogeneities in the early

universe, has allowed cosmologists to precisely calculate the angular power spectrum of the radiation, and it has been measured by the recent satellite experiments (COBE and WMAP) and many ground and balloon-based experiments (such as Degree Angular Scale Interferometer, Cosmic Background Imager, and Boomerang). One of the goals of these efforts is to measure the basic parameters of the Lambda-CDM model

with increasing accuracy, as well as to test the predictions of the Big

Bang model and look for new physics. The results of measurements made

by WMAP, for example, have placed limits on the neutrino masses.

Newer experiments, such as QUIET and the Atacama Cosmology Telescope, are trying to measure the polarization of the cosmic microwave background.

These measurements are expected to provide further confirmation of the

theory as well as information about cosmic inflation, and the so-called

secondary anisotropies, such as the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect and Sachs-Wolfe effect, which are caused by interaction between galaxies and clusters with the cosmic microwave background.

On 17 March 2014, astronomers of the BICEP2 Collaboration announced the apparent detection of B-mode polarization of the CMB, considered to be evidence of primordial gravitational waves that are predicted by the theory of inflation to occur during the earliest phase of the Big Bang. However, later that year the Planck collaboration provided a more accurate measurement of cosmic dust, concluding that the B-mode signal from dust is the same strength as that reported from BICEP2. On 30 January 2015, a joint analysis of BICEP2 and Planck data was published and the European Space Agency announced that the signal can be entirely attributed to interstellar dust in the Milky Way.

Formation and evolution of large-scale structure

Understanding the formation and evolution of the largest and earliest structures (i.e., quasars, galaxies, clusters and superclusters) is one of the largest efforts in cosmology. Cosmologists study a model of hierarchical structure formation

in which structures form from the bottom up, with smaller objects

forming first, while the largest objects, such as superclusters, are

still assembling.

One way to study structure in the universe is to survey the visible

galaxies, in order to construct a three-dimensional picture of the

galaxies in the universe and measure the matter power spectrum. This is the approach of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey.

Another tool for understanding structure formation is

simulations, which cosmologists use to study the gravitational

aggregation of matter in the universe, as it clusters into filaments, superclusters and voids. Most simulations contain only non-baryonic cold dark matter,

which should suffice to understand the universe on the largest scales,

as there is much more dark matter in the universe than visible, baryonic

matter. More advanced simulations are starting to include baryons and

study the formation of individual galaxies. Cosmologists study these

simulations to see if they agree with the galaxy surveys, and to

understand any discrepancy.

Other, complementary observations to measure the distribution of matter in the distant universe and to probe reionization include:

- The Lyman-alpha forest, which allows cosmologists to measure the distribution of neutral atomic hydrogen gas in the early universe, by measuring the absorption of light from distant quasars by the gas.

- The 21 centimeter absorption line of neutral atomic hydrogen also provides a sensitive test of cosmology.

- Weak lensing, the distortion of a distant image by gravitational lensing due to dark matter.

These will help cosmologists settle the question of when and how structure formed in the universe.

Dark matter

Evidence from Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the cosmic microwave background, structure formation, and galaxy rotation curves suggests that about 23% of the mass of the universe consists of non-baryonic dark matter, whereas only 4% consists of visible, baryonic matter. The gravitational effects of dark matter are well understood, as it behaves like a cold, non-radiative fluid that forms haloes

around galaxies. Dark matter has never been detected in the laboratory,

and the particle physics nature of dark matter remains completely

unknown. Without observational constraints, there are a number of

candidates, such as a stable supersymmetric particle, a weakly interacting massive particle, a gravitationally-interacting massive particle, an axion, and a massive compact halo object. Alternatives to the dark matter hypothesis include a modification of gravity at small accelerations (MOND) or an effect from brane cosmology.

Dark energy

If the universe is flat,

there must be an additional component making up 73% (in addition to the

23% dark matter and 4% baryons) of the energy density of the universe.

This is called dark energy. In order not to interfere with Big Bang

nucleosynthesis and the cosmic microwave background, it must not cluster

in haloes like baryons and dark matter. There is strong observational

evidence for dark energy, as the total energy density of the universe is

known through constraints on the flatness of the universe, but the

amount of clustering matter is tightly measured, and is much less than

this. The case for dark energy was strengthened in 1999, when

measurements demonstrated that the expansion of the universe has begun

to gradually accelerate.

Apart from its density and its clustering properties, nothing is known about dark energy. Quantum field theory predicts a cosmological constant (CC) much like dark energy, but 120 orders of magnitude larger than that observed. Steven Weinberg and a number of string theorists have invoked the 'weak anthropic principle':

i.e. the reason that physicists observe a universe with such a small

cosmological constant is that no physicists (or any life) could exist in

a universe with a larger cosmological constant. Many cosmologists find

this an unsatisfying explanation: perhaps because while the weak

anthropic principle is self-evident (given that living observers exist,

there must be at least one universe with a cosmological constant which

allows for life to exist) it does not attempt to explain the context of

that universe. For example, the weak anthropic principle alone does not distinguish between:

- Only one universe will ever exist and there is some underlying principle that constrains the CC to the value we observe.

- Only one universe will ever exist and although there is no underlying principle fixing the CC, we got lucky.

- Lots of universes exist (simultaneously or serially) with a range of CC values, and of course ours is one of the life-supporting ones.

Other possible explanations for dark energy include quintessence or a modification of gravity on the largest scales. The effect on cosmology of the dark energy that these models describe is given by the dark energy's equation of state, which varies depending upon the theory. The nature of dark energy is one of the most challenging problems in cosmology.

A better understanding of dark energy is likely to solve the problem of the ultimate fate of the universe. In the current cosmological epoch, the accelerated expansion due to dark energy is preventing structures larger than superclusters from forming. It is not known whether the acceleration will continue indefinitely, perhaps even increasing until a big rip, or whether it will eventually reverse, lead to a big freeze, or follow some other scenario.

Gravitational waves

Gravitational waves are ripples in the curvature of spacetime that propagate as waves at the speed of light, generated in certain gravitational interactions that propagate outward from their source. Gravitational-wave astronomy is an emerging branch of observational astronomy which aims to use gravitational waves to collect observational data about sources of detectable gravitational waves such as binary star systems composed of white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes; and events such as supernovae, and the formation of the early universe shortly after the Big Bang.

In 2016, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration teams announced that they had made the first observation of gravitational waves, originating from a pair of merging black holes using the Advanced LIGO detectors. On 15 June 2016, a second detection of gravitational waves from coalescing black holes was announced. Besides LIGO, many other gravitational-wave observatories (detectors) are under construction.

Other areas of inquiry

Cosmologists also study:

- Whether primordial black holes were formed in our universe, and what happened to them.

- Detection of cosmic rays with energies above the GZK cutoff, and whether it signals a failure of special relativity at high energies.

- The equivalence principle, whether or not Einstein's general theory of relativity is the correct theory of gravitation, and if the fundamental laws of physics are the same everywhere in the universe.

- The increasing complexity of universal structures, an example being the progressively greater energy rate density.