The AIDS epidemic, caused by HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), found its way to the United States as early as 1960, but was first noticed after doctors discovered clusters of Kaposi's sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia

in gay men in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco in 1981.

Treatment of HIV/AIDS is primarily via a "drug cocktail" of antiretroviral drugs, and education programs to help people avoid infection.

Initially, infected foreign nationals were turned back at the

U.S. border to help prevent additional infections. The number of U.S.

deaths from AIDS have declined sharply since the early years of the

disease's presentation domestically. In the United States, 1.2 million

people live with an HIV infection, of whom 15% are unaware of their

infection. Gay and bisexual men, African Americans, and Latinos remain disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS in the U.S.

Mortality and morbidity

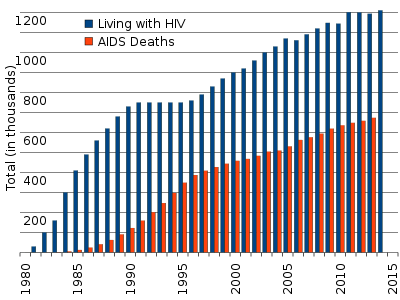

As of 2016, about 675,000 people have died of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. since the beginning of the HIV epidemic.

With improved treatments and better prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, death rates have quite significantly declined.

The overall death rate among persons diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in New York City decreased by sixty-two percent from 2001 to 2012.

Containment

Medical treatment

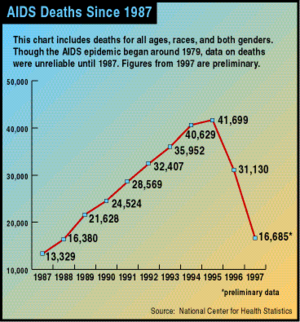

A chart of AIDS deaths in the United States from 1987 to 1997.

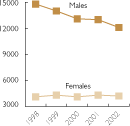

A chart of AIDS deaths in the United States from 1998 to 2002.

Great progress was made in the U.S. following the introduction of three-drug anti-HIV treatments ("cocktails") that included antiretroviral drugs. David Ho, a pioneer of this approach, was honored as Time Magazine

Man of the Year for 1996. Deaths were rapidly reduced by more than

half, with a small but welcome reduction in the yearly rate of new HIV

infections. Since this time, AIDS deaths have continued to decline, but

much more slowly, and not as completely in black Americans as in other

population segments.

Travel restrictions

The

second prong of the American approach to containment has been to

maintain strict entry controls to the country for people with HIV or

AIDS. Under legislation enacted by the United States Congress

in 1993, patients found importing anti-HIV medication into the country

were arrested and placed on flights back to their country of origin.

Some HIV-positive travelers took to sending anti-HIV medication

through the post to friends or contacts in advocacy groups in advance.

This meant that the traveller would not be discovered with any

medication. However, the security clampdown following the September 11 attacks in 2001 meant this was no longer an option.

The only legal alternative to this was to apply for a special visa

beforehand, which entailed an interview at an American Embassy,

confiscation of the passport during the lengthy application process, and

then, if permission were granted, a permanent attachment being made to

the applicant's passport. This process was condemned as intrusive and invasive by a number

of advocacy groups, on the grounds that any time the passport was later

used for travel elsewhere or for identification purposes, the holder's

HIV status would become known. It was also felt that this rule was

unfair because it applied even if the traveller was covered for

HIV-related conditions under their own travel insurance.

In early December 2006, President George W. Bush indicated that he would issue an executive order allowing HIV-positive people to enter the United States on standard visas. It was unclear whether applicants would still have to declare their HIV status. However, the ban remained in effect throughout Bush's Presidency. In August 2007, Congresswoman Barbara Lee of California introduced H.R. 3337,

the HIV Nondiscrimination in Travel and Immigration Act of 2007. This

bill would have allowed travelers and immigrants entry to the United

States without having to disclose their HIV status. The bill died at the

end of the 110th Congress.

In July 2008, then President George W. Bush signed H.R. 5501 that lifted the ban in statutory law. However, the United States Department of Health and Human Services

still held the ban in administrative (written regulation) law. New

impetus was added to repeal efforts when Paul Thorn, a UK tuberculosis

expert who was invited to speak at the 2009 Pacific Health Summit

in Seattle, was denied a visa due to his HIV positive status. A letter

written by Mr. Thorn, and read in his place at the Summit, was obtained

by Congressman Jim McDermott, who advocated the issue to the Obama administration's Health Secretary.

On October 30, 2009 President Barack Obama reauthorized the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Bill which expanded care and treatment through federal funding to nearly half a million.

He also announced that the Department of Health and Human Services

crafted regulation that would end the HIV Travel and Immigration Ban

effective in January 2010; on January 4, 2010, the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention removed HIV infection from the list of "communicable diseases

of public health significance," due to it not being spread by casual

contact, or by air, food or water, and removed HIV status as a factor to

be considered in the granting of travel visas, disallowing HIV status from among the diseases that could prevent people who are not U.S. citizens from entering the country.

Public perception

The number of people living with HIV in the United States, and the total cumulative number of deaths.

One of the best known works on the history of HIV is 1987's book And the Band Played On, by Randy Shilts. Shilts contends that Ronald Reagan's

administration dragged its feet in dealing with the crisis due to

homophobia, while the gay community viewed early reports and public

health measures with corresponding distrust, thus allowing the disease

to infect hundreds of thousands more. This resulted in the formation of

ACT-UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power by Larry Kramer.

Galvanized by the federal government's inactivity, the movement by AIDS

activists to gain funding for AIDS research, which on a per-patient

basis out-paced funding for more prevalent diseases such as cancer and

heart disease, was used as a model for future lobbying for health

research funding.

The Shilts work popularized the misconception that the disease was introduced by a gay flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas, referred to as "Patient Zero,"

although the author did not actually make this claim in the book.

However, subsequent research has revealed that there were cases of AIDS

much earlier than initially known. HIV-infected blood samples have been

found from as early as 1959 in Africa (see HIV main entry), and HIV has been shown to have caused the death of Robert Rayford,

a 16-year-old St. Louis male, in 1969, who could have contracted it as

early as 7 years old due to sexual abuse, suggesting that HIV had been

present, at very low prevalence, in the U.S. since before the 1970s.

An early theory asserted that a series of inoculations against hepatitis B that were performed in the gay community of San Francisco were tainted with HIV. Although there was a high correlation between recipients of that vaccination and initial cases of AIDS, this theory has long been discredited. HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C are bloodborne diseases with very similar modes of transmission, and those at risk for one are at risk for the others.

Activists and critics of current AIDS policies allege that

another preventable impediment to stemming the spread of the disease

and/or finding a treatment was the vanity of "celebrity" scientists. Robert Gallo, an American scientist involved in the search for a new virus in the people affected by the disease, became embroiled in a legal battle with French scientist Luc Montagnier,

who had first discovered such a virus in tissue cultures derived from a

patient suffering from enlargement of the lymphnodes (an early sign of

AIDS). Montagnier had named the new virus LAV

(Lymphoadenopathy-Associated Virus).

Gallo, who appeared to question the primacy of the French

scientist's discovery, refused to recognize the "French virus" as the

cause of AIDS, and tried instead to claim the disease was caused by a

new member of a retrovirus family, HTLV,

which he had discovered. Critics claim that because some scientists

were more interested in trying to win a Nobel prize than in helping

patients, research progress was delayed and more people needlessly died.

After a number of meetings and high-level political intervention, the

French scientists and Gallo agreed to "share" the discovery of HIV,

although eventually Montagnier and his group were recognized as the true

discoverers, and won the 2008 Nobel Prize for it.

Publicity campaigns were started in attempts to counter the

incorrect and often vitriolic perception of AIDS as a "gay plague".

These included the Ryan White case, red ribbon campaigns, celebrity dinners, the 1993 film version of And the Band Played On, sex education programs in schools, and television advertisements. Announcements by various celebrities that they had contracted HIV (including actor Rock Hudson, basketball star Magic Johnson, tennis player Arthur Ashe and singer Freddie Mercury)

were significant in arousing media attention and making the general

public aware of the dangers of the disease to people of all sexual

orientations.

By race/ethnicity

African Americans

continue to experience the most severe burden of HIV, compared with

other races and ethnicities. Black people represent approximately 13% of

the U.S. population, but accounted for an estimated 43% of new HIV

infections in 2017.

Furthermore, they make up nearly 52% of AIDS-related deaths in America.

While the overall rates of HIV incidences and prevalence have

decreased, they have increased in one particular demographic: African

American gay and bisexual men (a 4% increase). In America, black

households were reported to have the lowest median income, leading to

lower rates of insured individuals. This creates cost barriers to

antiretroviral treatments.

Hispanics/Latinos are also disproportionately affected by

HIV. Hispanics/Latinos represented 16% of the population but accounted

for 21% of new HIV infections in 2010. Hispanics/Latinos accounted for

20% of people living with HIV infection in 2011. Disparities persist in

the estimated rate of new HIV infections in Hispanics/Latinos. In 2010,

the rate of new HIV infections for Latino males was 2.9 times that for

white males, and the rate of new infections for Latinas was 4.2 times

that for white females. Since the epidemic began, more than 100,888

Hispanics/Latinos with an AIDS diagnosis have died, including 2,155 in

2012.

American Indian/Alaskan Native Communities in the United

States also see a higher rate of HIV/AIDS in comparison to whites,

Asians, and Native Hawaiians/other Native Pacific Islanders. Although

AI/AN sufferers of HIV/AIDS only represent roughly 1% of all sufferers

in the U.S.[16],

the number of diagnoses amongst AI/AN gay and bisexual men rose by 54%

between 2011 and 2015. Additionally, the survival rate of diagnosed

AI/AN was the lowest of all races in the United States between 1998 and

2005 . In recent years, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have put in place a “high impact prevention approach”

in partnership with the Indian Health Service and the CDC Tribal

Advisory Committee to tackle the growing rates in a culturally

appropriate way.

The higher rate of HIV/AIDS cases amongst AI/AN people have been

attributed to a number of factors including socioeconomic disadvantages

faced by AI/AN communities, which may result in difficulty accessing

healthcare and high-quality housing. It may be more difficult for gay

and bisexual AI/AN men to access healthcare due to living in rural

communities, or due to stigma attached to their sexualities. AI/AN

people have also been reported to have higher rates of other STIs,

including chlamydia and gonorrhea, which also increases likeliness of

contracting or transmitting HIV.

Furthermore, as there are over 560 federally recognised AI/AN tribes,

there is some difficulty in creating outreach programmes which

effectively appeal to all tribes whilst remaining culturally

appropriate. As well as fear of stigma from within AI/AN communities,

there may also be a fear amongst LGBTQ+ AI/AN of a lack of understanding

from health professionals in the United States, particularly amongst Two Spirit

people. A 2013 NASTAD report calls for the inclusion of LGBT and Two

Spirit AI/AN in HIV/AID program planning and asserts that “health

departments should utilize local experts to better understand regional

definitions of “Two Spirit” and incorporate modules on Native gay men

and Two Spirit people into cultural sensitivity courses for public

health service providers”.

"Down-Low" culture amongst Black MSM

Down-low is an African American slang term that typically refers to a subculture of Black men who usually identify as heterosexual, but who have sex with men; some avoid sharing this information even if they have female sexual partner(s) married or single.

According to a study published in the Journal of Bisexuality,

"[t]he Down Low is a lifestyle predominately practiced by young, urban

Black men who have sex with other men and women, yet do not identify as

gay or bisexual".

In this context, "being on the Down Low" is more than just men having sex with men in secret, or a variant of closeted

homosexuality or bisexuality—it is a sexual identity that is, at least

partly, defined by its "cult of masculinity" and its rejection of what

is perceived as White culture (including white LGBT culture) and terms. A 2003 New York Times Magazine cover story on the Down Low phenomenon explains that the Black community sees "homosexuality as a White man's perversion."

The CDC

cited three findings that relate to African-American men who operate on

the down-low (engage in MSM activity but don't disclose to others):

- African American men who have sex with men (MSM), but who do not disclose their sexual orientation (nondisclosers), have a high prevalence of HIV infection (14%); nearly three times higher than nondisclosing MSMs of all other races/ethnicities combined (5%).

- Confirming previous research, the study of 5,589 MSM, aged 15–29 years, in six U.S. cities found that African American MSM were more likely not to disclose their sexual orientation compared with White MSM (18% vs. 8%).

- HIV-infected nondisclosers were less likely to know their HIV status (98% were unaware of their infection compared with 75% of HIV-positive disclosers), and more likely to have had recent female sex partners.

Risk Factors contributing to the Black HIV rate

Accessibility to healthcare is very important in preventing and

treating HIV/AIDs. It can be affected by health insurance which is

available to people through private insurers, Medicare and Medicaid which leaves some people still vulnerable. Historically, African Americans have faced discrimination when it comes to receiving healthcare.

During the time of slavery, slave owners would get medical attention

for slaves because they were deemed as property, while slaves that the

slave owners believed were not able to recover were sent to be

experimented on. In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth

century, universities dug up African American bodies to autopsy, and

some night doctors would snatch people off the streets to examine.

African Americans have been experimented on and exploited for centuries.

The Tuskegee Syphilis study experimented vulnerable men in the South

who had syphilis. They kept treatment from these men to see what would

happen. Henrietta Lacks was also exploited when researchers took her cancerous cells and grew them to experiment on them.

Homosexuality is viewed negatively in the African American

Community. "In a qualitative study of 745 racially and ethnic diverse

undergraduates attending a large Midwestern university, Calzo and Ward

(2009) determined that parents of African-American participants

discussed homosexuality more frequently than the parents of other

respondents. In analyses of the values communicated, Calzo and Ward

(2009) reported that Black parents offered greater indication that

homosexuality is perverse and unnatural".

Homosexuality is seen as a threat to the African American empowerment.

Masculinity is seen as important for the African American community

because it shows that the community is in control of their own destiny.

Since the stigma circling homosexuality is that it is “effeminate”, then

homosexuality is seen as a threat to masculinity. “Black manhood, then,

depends on men's ability to be provider, progenitor, and protector.

But, as the Black male performance of parts of this script is thwarted

by economic and cultural factors, the performance of Black masculinity

becomes predicated on a particular performance of Black sexuality and

avoidance of weakness and femininity. If sexuality remains one of the

few ways that Black men can recapture a masculinity withheld from them

in the marketplace, endorsing Black homosexuality subverts the cultural

project of reinscribing masculinity within the Black community." This

critical view is influenced by Internalized homophobia. “Internalized

homophobia is defined as the lesbian, gay, or bisexual individual's

inward direction of society's homophobic attitudes (Meyer 1995)."

The African American community's social norms regarding

homosexuality have influenced a higher percentage of African Americans

with internalized homophobia. This homophobic culture is sustained

within the African American community through the church because

religion is a vital part of the African American community: "As reported

by Peterson and Jones (2009), AA MSM tended to be more involved with

religious communities than NHW MSM." Because the church reiterates this

stigma of homosexuality, the African American community has higher rates

of internalized homophobia. This internalized homophobia causes a lower

chance of HIV/AIDS education on prevention and care within the African

American community.

Sex education varies throughout the United States and in some

areas could use more informative measures. African-Americans and

Hispanic/ Latinos experience higher rates of lower socioeconomic

statuses and fewer opportunities than white people. This causes limited

access to (higher) education in lower socioeconomic areas. Sex education

on HIV prevention has decreased from 64% (2000) to 41% (2014). Out of

the 50 states, 26 put a larger emphasis on abstinence sex education.

Abstinence only sex education is correlated to increasing rates of HIV

especially in teenagers and young adults.

With mass incarceration of the African American community, HIV has been spreading rapidly throughout jails and prisons.

“Among jail populations, African American men are 5 times as likely as

white men, and twice as likely as Hispanic/Latino men, to be diagnosed

with HIV.” Since most people contract HIV before being incarcerated, it

is hard to know who has the disease and to keep it from spreading. A

lack of hygiene in prisons perpetuates these problems. Many inmates do

not disclose their high-risk behaviors, such as anal sex or injection

drug use, because they fear being stigmatized and ostracized by other

inmates.There is also a lack of educational programs on disease

prevention for inmates. Because “nine out of ten jail inmates are

released in under 72 hours which makes it hard to test them for HIV and

help them find treatment,” the problem persists outside of prison.

Activism and response

Starting

in the early 1980s, AIDS activist groups and organizations began to

emerge and advocate for people infected with HIV in the United States.

Though it was an important aspect of the movement, activism went beyond

the pursuit of funding for AIDS research. Groups acted to educate and

raise awareness of the disease and its effects on different populations,

even those thought to be at low-risk of contracting HIV. This was done

through publications and “alternative media” created by those living

with or close to the disease.

Activist groups worked to prevent spread of HIV by distributing

information about safe sex. They also existed to support people living

with HIV/AIDS, offering therapy, support groups, and hospice care. Organizations like Gay Men's Health Crisis,

the Lesbian AIDS Project, and SisterLove were created to address the

needs of certain populations living with HIV/AIDS. Other groups, like

the NAMES Project,

emerged as a way of memorializing those who had passed, refusing to let

them be forgotten by the historical narrative. One group, the

Association for Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment (ADAPT), headed by Yolanda Serrano, coordinated with their local prison, Riker's Island Correctional Facility,

to advocate for those imprisoned and AIDS positive to be released

early, so that they could pass away in the comfort of their own homes.

Both men and women, heterosexual and queer populations were

active in establishing and maintaining these parts of the movement.

Because AIDS was initially thought only to impact gay men, most

narratives of activism focus on their contributions to the movement.

However, women also played a significant role in raising awareness,

rallying for change, and caring for those impacted by the disease.

Lesbians helped organize and spread information about transmission

between women, as well as supporting gay men in their work. Narratives

of activism also tend to focus on organizing done in coastal cities, but

AIDS activism was present and widespread across both urban and more

rural areas of the United States. Organizers sought to address needs

specific to their communities, whether that was working to establish needle exchange programs,

fighting against housing or employment discrimination, or issues faced

primarily by people identified as members of specific groups (such as

sex workers, mothers and children, or incarcerated people).

Present day activism

An

effective response to HIV/AIDS requires that groups of vulnerable

populations have access to HIV prevention programs with information and

services that are specific to them.

In the present day, some activist groups and AIDS organizations that

were established during the height of the epidemic are still present and

working to assist people living with AIDS.

They may offer any combination of the following: health education,

counseling and support, or advocacy for law and policy. AIDS

organizations also continue to call for public awareness and support

through participation in events like pride parades, World AIDS Day, or AIDS walks. Newer activism has appeared in advocacy forPre-Exposure Prophylaxis

(PrEP), which has shown to significantly limit transmission of HIV.

While PrEP appears to be extremely successful in suppressing the spread

of HIV infection, there is some evidence that the reduction in HIV risk

has led to some people taking more sexual risks, specifically, reduced

use of condoms in anal sex.

Current status

The CDC estimates that 1,122,900 U.S. residents aged 13 years and older are living with HIV infection as of 2016, including 162,500 (15%) who are unaware of their infection.

Over the past decade, the number of people living with HIV has

increased, while the annual number of new HIV infections has declined to

about 40,000 new HIV infections.

Within the overall estimates, however, some groups are affected more

than others. MSM continue to bear the greatest burden of HIV infection,

and among races/ethnicities, African Americans continue to be

disproportionately affected.

An estimated 15,807 people with an AIDS diagnosis died in 2016,

and approximately 658,507 people in the United States with an AIDS

diagnosis have died overall. The deaths of persons with an AIDS

diagnosis can be due to any cause—that is, the death may or may not be

related to AIDS.

In California alone, 184,429 HIV cases (including children) were reported by December 2008. Of those, 85,958 have died, with 31,076 in Los Angeles County, 18,838 in San Francisco, and 7,135 in San Diego County.

In 2015, 48,824 people were living with HIV (not AIDS) in the state of New York, with 38,441 in New York City alone.

Washington, D.C. has a particularly high incidence of HIV/AIDS, with 177 new cases annually per 100,000 people as of 2012, more than nine times higher than any state.

In the United States, men who have sex with men (MSM), described as gay and bisexual,

make up about 55% of the total HIV-positive population, and 67% of new

HIV cases and 83% of the estimated new HIV diagnoses among all

males aged 13 and older, and an estimated 92% of new HIV diagnoses among

all men in their age group (2014 report). 1 in 6 gay and bisexual men

are therefore expected to be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime if

current rates continue. Gay and bisexual men accounted for an estimated

54% of people diagnosed with AIDS, with 39% being African American, 32%

being white, and 24% being Hispanic/Latino. The CDC estimates that more than 600,000 gay and bisexual men are currently living with HIV in the United States. A review of four studies in which trans women in the United States were tested for HIV found that 27.7% tested positive.

In a 2008 study, the Center for Disease Control found that, of

the study participants who were men who had sex with men ("MSM"), almost

one in five (19%) had HIV and "among those who were infected, nearly

half (44 percent) were unaware of their HIV status." The research found

that white MSM "represent a greater number of new HIV infections than

any other population, followed closely by black MSM—who are one of the

most disproportionately affected subgroups in the U.S." and that most

new infections among white MSM occurred among those aged 30–39 followed

closely by those aged 40–49, while most new infections among black MSM

have occurred among young black MSM (aged 13–29).

In 2015, a major HIV outbreak, Indiana's

largest-ever, occurred in two largely rural, economically depressed and

poor counties in the southern portion of the state, due to the

injection of a relatively new opioid-type drug called Opana (oxymorphone),

which is designed be taken in pill form but is ground up and injected

intravenously using needles. Because of the lack of HIV cases in that

area beforehand and the youth of many but not all of those affected, the

relative unavailability in the local area of safe needle exchange

programs and of treatment centers capable of dealing with long-term

health needs, HIV care, and drug addiction during the initial phases of

the outbreak, it was not initially adequately contained and dealt with

until those were set up by the government, and acute awareness of the

issue spread. Such centers have now been opened, and short-term care is

beginning to be provided; once the scope of the outbreak became clear,

Governor Mike Pence,

despite some initial reservations, approved a legislative measure to

allow safe, clean needle exchange programs and treatment for those

affected, which could end up being instituted statewide.