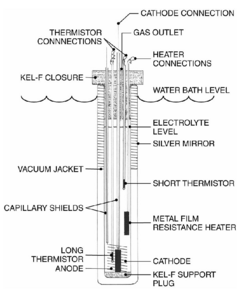

Diagram of an open-type calorimeter used at the New Hydrogen Energy Institute in Japan

Cold fusion is a hypothesized type of nuclear reaction that would occur at, or near, room temperature. It would contrast starkly with the "hot" fusion that is known to take place naturally within stars and artificially in hydrogen bombs and prototype fusion reactors under immense pressure and at temperatures of millions of degrees, and be distinguished from muon-catalyzed fusion. There is currently no accepted theoretical model that would allow cold fusion to occur.

In 1989, two electrochemists, Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons,

reported that their apparatus had produced anomalous heat ("excess

heat") of a magnitude they asserted would defy explanation except in

terms of nuclear processes. They further reported measuring small amounts of nuclear reaction byproducts, including neutrons and tritium. The small tabletop experiment involved electrolysis of heavy water on the surface of a palladium (Pd) electrode. The reported results received wide media attention and raised hopes of a cheap and abundant source of energy.

Many scientists tried to replicate the experiment with the few

details available. Hopes faded due to the large number of negative

replications, the withdrawal of many reported positive replications, the

discovery of flaws and sources of experimental error in the original

experiment, and finally the discovery that Fleischmann and Pons had not

actually detected nuclear reaction byproducts. By late 1989, most scientists considered cold fusion claims dead, and cold fusion subsequently gained a reputation as pathological science. In 1989 the United States Department of Energy

(DOE) concluded that the reported results of excess heat did not

present convincing evidence of a useful source of energy and decided

against allocating funding specifically for cold fusion. A second DOE

review in 2004, which looked at new research, reached similar

conclusions and did not result in DOE funding of cold fusion.

A small community of researchers continues to investigate cold fusion, now often preferring the designation low-energy nuclear reactions (LENR) or condensed matter nuclear science (CMNS). Since articles about cold fusion are rarely published in peer-reviewed mainstream scientific journals any longer, they do not attract the level of scrutiny expected for mainstream scientific publications.

History

Nuclear fusion is normally understood to occur at temperatures in the tens of millions of degrees. This is called "thermonuclear fusion". Since the 1920s, there has been speculation that nuclear fusion might be possible at much lower temperatures by catalytically

fusing hydrogen absorbed in a metal catalyst. In 1989, a claim by

Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann (then one of the world's leading electrochemists) that such cold fusion had been observed caused a brief media sensation

before the majority of scientists criticized their claim as incorrect

after many found they could not replicate the excess heat. Since the

initial announcement, cold fusion research has continued by a small

community of researchers who believe that such reactions happen and hope

to gain wider recognition for their experimental evidence.

Early research

The ability of palladium to absorb hydrogen was recognized as early as the nineteenth century by Thomas Graham. In the late 1920s, two Austrian born scientists, Friedrich Paneth and Kurt Peters,

originally reported the transformation of hydrogen into helium by

nuclear catalysis when hydrogen was absorbed by finely divided palladium

at room temperature. However, the authors later retracted that report,

saying that the helium they measured was due to background from the air.

In 1927 Swedish scientist John Tandberg reported that he had fused hydrogen into helium in an electrolytic cell with palladium electrodes. On the basis of his work, he applied for a Swedish patent for "a method to produce helium and useful reaction energy". Due to Paneth and Peters's retraction and his inability to explain the physical process, his patent application was denied. After deuterium was discovered in 1932, Tandberg continued his experiments with heavy water. The final experiments made by Tandberg with heavy water were similar to the original experiment by Fleischmann and Pons. Fleischmann and Pons were not aware of Tandberg's work.

The term "cold fusion" was used as early as 1956 in a New York Times article about Luis Alvarez's work on muon-catalyzed fusion. Paul Palmer and then Steven Jones of Brigham Young University

used the term "cold fusion" in 1986 in an investigation of

"geo-fusion", the possible existence of fusion involving hydrogen

isotopes in a planetary core.

In his original paper on this subject with Clinton Van Siclen,

submitted in 1985, Jones had coined the term "piezonuclear fusion".

Fleischmann–Pons experiment

The

most famous cold fusion claims were made by Stanley Pons and Martin

Fleischmann in 1989. After a brief period of interest by the wider

scientific community, their reports were called into question by nuclear

physicists. Pons and Fleischmann never retracted their claims, but

moved their research program to France after the controversy erupted.

Events preceding announcement

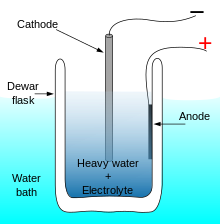

Electrolysis cell schematic

Martin Fleischmann of the University of Southampton and Stanley Pons of the University of Utah hypothesized that the high compression ratio and mobility of deuterium that could be achieved within palladium metal using electrolysis might result in nuclear fusion.

To investigate, they conducted electrolysis experiments using a

palladium cathode and heavy water within a calorimeter, an insulated

vessel designed to measure process heat. Current was applied

continuously for many weeks, with the heavy water being renewed at intervals.

Some deuterium was thought to be accumulating within the cathode, but

most was allowed to bubble out of the cell, joining oxygen produced at

the anode.

For most of the time, the power input to the cell was equal to the

calculated power leaving the cell within measurement accuracy, and the

cell temperature was stable at around 30 °C. But then, at some point (in

some of the experiments), the temperature rose suddenly to about 50 °C

without changes in the input power. These high temperature phases would

last for two days or more and would repeat several times in any given

experiment once they had occurred. The calculated power leaving the cell

was significantly higher than the input power during these high

temperature phases. Eventually the high temperature phases would no

longer occur within a particular cell.

In 1988 Fleischmann and Pons applied to the United States Department of Energy

for funding towards a larger series of experiments. Up to this point

they had been funding their experiments using a small device built with

$100,000 out-of-pocket. The grant proposal was turned over for peer review, and one of the reviewers was Steven Jones of Brigham Young University. Jones had worked for some time on muon-catalyzed fusion,

a known method of inducing nuclear fusion without high temperatures,

and had written an article on the topic entitled "Cold nuclear fusion"

that had been published in Scientific American in July 1987. Fleischmann and Pons and co-workers met with Jones and co-workers on occasion in Utah

to share research and techniques. During this time, Fleischmann and

Pons described their experiments as generating considerable "excess

energy", in the sense that it could not be explained by chemical reactions alone. They felt that such a discovery could bear significant commercial value and would be entitled to patent protection. Jones, however, was measuring neutron flux, which was not of commercial interest.

To avoid future problems, the teams appeared to agree to publish their

results simultaneously, though their accounts of their 6 March meeting

differ.

Announcement

In

mid-March 1989, both research teams were ready to publish their

findings, and Fleischmann and Jones had agreed to meet at an airport on

24 March to send their papers to Nature via FedEx. Fleischmann and Pons, however, pressured by the University of Utah, which wanted to establish priority on the discovery, broke their apparent agreement, disclosing their work at a press conference on 23 March (they claimed in the press release that it would be published in Nature but instead submitted their paper to the Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry). Jones, upset, faxed in his paper to Nature after the press conference.

Fleischmann and Pons' announcement drew wide media attention. But the 1986 discovery of high-temperature superconductivity

had made the scientific community more open to revelations of

unexpected scientific results that could have huge economic

repercussions and that could be replicated reliably even if they had not

been predicted by established theories. Many scientists were also reminded of the Mössbauer effect, a process involving nuclear transitions

in a solid. Its discovery 30 years earlier had also been unexpected,

though it was quickly replicated and explained within the existing

physics framework.

The announcement of a new purported clean source of energy came at a crucial time: adults still remembered the 1973 oil crisis and the problems caused by oil dependence, anthropogenic global warming was starting to become notorious, the anti-nuclear movement was labeling nuclear power plants as dangerous and getting them closed, people had in mind the consequences of strip mining, acid rain, the greenhouse effect and the Exxon Valdez oil spill, which happened the day after the announcement. In the press conference, Chase N. Peterson,

Fleischmann and Pons, backed by the solidity of their scientific

credentials, repeatedly assured the journalists that cold fusion would

solve environmental problems, and would provide a limitless

inexhaustible source of clean energy, using only seawater as fuel. They said the results had been confirmed dozens of times and they had no doubts about them.

In the accompanying press release Fleischmann was quoted saying: "What

we have done is to open the door of a new research area, our indications

are that the discovery will be relatively easy to make into a usable

technology for generating heat and power, but continued work is needed,

first, to further understand the science and secondly, to determine its

value to energy economics."

Response and fallout

Although

the experimental protocol had not been published, physicists in several

countries attempted, and failed, to replicate the excess heat

phenomenon. The first paper submitted to Nature reproducing

excess heat, although it passed peer review, was rejected because most

similar experiments were negative and there were no theories that could

explain a positive result; this paper was later accepted for publication by the journal Fusion Technology. Nathan Lewis, professor of chemistry at the California Institute of Technology, led one of the most ambitious validation efforts, trying many variations on the experiment without success, while CERN physicist Douglas R. O. Morrison said that "essentially all" attempts in Western Europe had failed. Even those reporting success had difficulty reproducing Fleischmann and Pons' results. On 10 April 1989, a group at Texas A&M University published results of excess heat and later that day a group at the Georgia Institute of Technology

announced neutron production—the strongest replication announced up to

that point due to the detection of neutrons and the reputation of the

lab. On 12 April Pons was acclaimed at an ACS meeting.

But Georgia Tech retracted their announcement on 13 April, explaining

that their neutron detectors gave false positives when exposed to heat. Another attempt at independent replication, headed by Robert Huggins at Stanford University, which also reported early success with a light water control, became the only scientific support for cold fusion in 26 April US Congress hearings. But when he finally presented his results he reported an excess heat of only one degree Celsius, a result that could be explained by chemical differences between heavy and light water in the presence of lithium. He had not tried to measure any radiation and his research was derided by scientists who saw it later.

For the next six weeks, competing claims, counterclaims, and suggested

explanations kept what was referred to as "cold fusion" or "fusion

confusion" in the news.

In April 1989, Fleischmann and Pons published a "preliminary note" in the Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. This paper notably showed a gamma peak without its corresponding Compton edge, which indicated they had made a mistake in claiming evidence of fusion byproducts. Fleischmann and Pons replied to this critique,

but the only thing left clear was that no gamma ray had been registered

and that Fleischmann refused to recognize any mistakes in the data. A much longer paper published a year later went into details of calorimetry but did not include any nuclear measurements.

Nevertheless, Fleischmann and Pons and a number of other

researchers who found positive results remained convinced of their

findings.

The University of Utah asked Congress to provide $25 million to pursue

the research, and Pons was scheduled to meet with representatives of

President Bush in early May.

On 30 April 1989 cold fusion was declared dead by the New York Times. The Times called it a circus the same day, and the Boston Herald attacked cold fusion the following day.

On 1 May 1989 the American Physical Society

held a session on cold fusion in Baltimore, including many reports of

experiments that failed to produce evidence of cold fusion. At the end

of the session, eight of the nine leading speakers stated that they

considered the initial Fleischmann and Pons claim dead, with the ninth, Johann Rafelski, abstaining. Steven E. Koonin of Caltech called the Utah report a result of "the incompetence and delusion of Pons and Fleischmann," which was met with a standing ovation. Douglas R. O. Morrison, a physicist representing CERN, was the first to call the episode an example of pathological science.

On 4 May, due to all this new criticism, the meetings with various representatives from Washington were cancelled.

From 8 May only the A&M tritium results kept cold fusion afloat.

In July and November 1989, Nature published papers critical of cold fusion claims. Negative results were also published in several other scientific journals including Science, Physical Review Letters, and Physical Review C (nuclear physics).

In August 1989, in spite of this trend, the state of Utah invested $4.5 million to create the National Cold Fusion Institute.

The United States Department of Energy organized a special panel to review cold fusion theory and research.

The panel issued its report in November 1989, concluding that results

as of that date did not present convincing evidence that useful sources

of energy would result from the phenomena attributed to cold fusion.

The panel noted the large number of failures to replicate excess heat

and the greater inconsistency of reports of nuclear reaction byproducts

expected by established conjecture.

Nuclear fusion of the type postulated would be inconsistent with

current understanding and, if verified, would require established

conjecture, perhaps even theory itself, to be extended in an unexpected

way. The panel was against special funding for cold fusion research, but

supported modest funding of "focused experiments within the general

funding system".

Cold fusion supporters continued to argue that the evidence for excess

heat was strong, and in September 1990 the National Cold Fusion

Institute listed 92 groups of researchers from 10 different countries

that had reported corroborating evidence of excess heat, but they

refused to provide any evidence of their own arguing that it could

endanger their patents. However, no further DOE nor NSF funding resulted from the panel's recommendation. By this point, however, academic consensus had moved decidedly toward labeling cold fusion as a kind of "pathological science".

In March 1990 Michael H. Salamon, a physicist from the University of Utah, and nine co-authors reported negative results.

University faculty were then "stunned" when a lawyer representing Pons

and Fleischmann demanded the Salamon paper be retracted under threat of a

lawsuit. The lawyer later apologized; Fleischmann defended the threat

as a legitimate reaction to alleged bias displayed by cold-fusion

critics.

In early May 1990 one of the two A&M researchers, Kevin Wolf,

acknowledged the possibility of spiking, but said that the most likely

explanation was tritium contamination in the palladium electrodes or

simply contamination due to sloppy work. In June 1990 an article in Science by science writer Gary Taubes destroyed the public credibility of the A&M tritium results when it accused its group leader John Bockris and one of his graduate students of spiking the cells with tritium. In October 1990 Wolf finally said that the results were explained by tritium contamination in the rods.

An A&M cold fusion review panel found that the tritium evidence was

not convincing and that, while they couldn't rule out spiking,

contamination and measurements problems were more likely explanations, and Bockris never got support from his faculty to resume his research.

On 30 June 1991 the National Cold Fusion Institute closed after it ran out of funds; it found no excess heat, and its reports of tritium production were met with indifference.

On 1 January 1991 Pons left the University of Utah and went to Europe. In 1992, Pons and Fleischman resumed research with Toyota Motor Corporation's IMRA lab in France.

Fleischmann left for England in 1995, and the contract with Pons was

not renewed in 1998 after spending $40 million with no tangible results. The IMRA laboratory stopped cold fusion research in 1998 after spending £12 million. Pons has made no public declarations since, and only Fleischmann continued giving talks and publishing papers.

Mostly in the 1990s, several books were published that were

critical of cold fusion research methods and the conduct of cold fusion

researchers. Over the years, several books have appeared that defended them.

Around 1998, the University of Utah had already dropped its research

after spending over $1 million, and in the summer of 1997, Japan cut off

research and closed its own lab after spending $20 million.

Subsequent research

A 1991 review by a cold fusion proponent had calculated "about 600 scientists" were still conducting research.

After 1991, cold fusion research only continued in relative obscurity,

conducted by groups that had increasing difficulty securing public

funding and keeping programs open. These small but committed groups of

cold fusion researchers have continued to conduct experiments using

Fleischmann and Pons electrolysis setups in spite of the rejection by

the mainstream community. The Boston Globe

estimated in 2004 that there were only 100 to 200 researchers working

in the field, most suffering damage to their reputation and career.

Since the main controversy over Pons and Fleischmann had ended, cold

fusion research has been funded by private and small governmental

scientific investment funds in the United States, Italy, Japan, and

India. For example, it was reported in Nature, in May, 2019, that Google had spent approximately $10 million on cold fusion research. A group of scientists at well-known research labs (e.g, MIT, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab,

and others) worked for several years to establish experimental

protocols and measurement techniques in an effort to re-evaluate cold

fusion to a high standard of scientific rigor. Their reported

conclusion: no cold fusion.

Current research

Cold fusion research continues today

in a few specific venues, but the wider scientific community has

generally marginalized the research being done and researchers have had

difficulty publishing in mainstream journals.

The remaining researchers often term their field Low Energy Nuclear

Reactions (LENR), Chemically Assisted Nuclear Reactions (CANR),

Lattice Assisted Nuclear Reactions (LANR), Condensed Matter Nuclear

Science (CMNS) or Lattice Enabled Nuclear Reactions; one of the reasons

being to avoid the negative connotations associated with "cold fusion". The new names avoid making bold implications, like implying that fusion is actually occurring.

The researchers who continue acknowledge that the flaws in the

original announcement are the main cause of the subject's

marginalization, and they complain of a chronic lack of funding and no possibilities of getting their work published in the highest impact journals.

University researchers are often unwilling to investigate cold fusion

because they would be ridiculed by their colleagues and their

professional careers would be at risk. In 1994, David Goodstein, a professor of physics at Caltech, advocated for increased attention from mainstream researchers and described cold fusion as:

A pariah field, cast out by the scientific establishment. Between cold fusion and respectable science there is virtually no communication at all. Cold fusion papers are almost never published in refereed scientific journals, with the result that those works don't receive the normal critical scrutiny that science requires. On the other hand, because the Cold-Fusioners see themselves as a community under siege, there is little internal criticism. Experiments and theories tend to be accepted at face value, for fear of providing even more fuel for external critics, if anyone outside the group was bothering to listen. In these circumstances, crackpots flourish, making matters worse for those who believe that there is serious science going on here.

United States

Cold fusion apparatus at the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center San Diego (2005)

United States Navy researchers at the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center (SPAWAR) in San Diego have been studying cold fusion since 1989. In 2002 they released a two-volume report, "Thermal and nuclear aspects of the Pd/D2O system," with a plea for funding. This and other published papers prompted a 2004 Department of Energy (DOE) review.

2004 DOE panel

In August 2003, the U.S. Secretary of Energy, Spencer Abraham, ordered the DOE to organize a second review of the field. This was thanks to an April 2003 letter sent by MIT's Peter L. Hagelstein,

and the publication of many new papers, including the Italian ENEA and

other researchers in the 2003 International Cold Fusion Conference, and a two-volume book by U.S. SPAWAR in 2002.

Cold fusion researchers were asked to present a review document of all

the evidence since the 1989 review. The report was released in 2004. The

reviewers were "split approximately evenly" on whether the experiments

had produced energy in the form of heat, but "most reviewers, even those

who accepted the evidence for excess power production, 'stated that the

effects are not repeatable, the magnitude of the effect has not

increased in over a decade of work, and that many of the reported

experiments were not well documented.'"

In summary, reviewers found that cold fusion evidence was still not

convincing 15 years later, and they didn't recommend a federal research

program.

They only recommended that agencies consider funding individual

well-thought studies in specific areas where research "could be helpful

in resolving some of the controversies in the field". They summarized its conclusions thus:

While significant progress has been made in the sophistication of calorimeters since the review of this subject in 1989, the conclusions reached by the reviewers today are similar to those found in the 1989 review. The current reviewers identified a number of basic science research areas that could be helpful in resolving some of the controversies in the field, two of which were: 1) material science aspects of deuterated metals using modern characterization techniques, and 2) the study of particles reportedly emitted from deuterated foils using state-of-the-art apparatus and methods. The reviewers believed that this field would benefit from the peer-review processes associated with proposal submission to agencies and paper submission to archival journals.

— Report of the Review of Low Energy Nuclear Reactions, US Department of Energy, December 2004

Cold fusion researchers placed a "rosier spin"

on the report, noting that they were finally being treated like normal

scientists, and that the report had increased interest in the field and

caused "a huge upswing in interest in funding cold fusion research." However, in a 2009 BBC article on an American Chemical Society's meeting on cold fusion, particle physicist Frank Close

was quoted stating that the problems that plagued the original cold

fusion announcement were still happening: results from studies are still

not being independently verified and inexplicable phenomena encountered

are being labelled as "cold fusion" even if they are not, in order to

attract the attention of journalists.

In February 2012, millionaire Sidney Kimmel, convinced that cold fusion was worth investing in by a 19 April 2009 interview with physicist Robert Duncan on the US news show 60 Minutes, made a grant of $5.5 million to the University of Missouri

to establish the Sidney Kimmel Institute for Nuclear Renaissance

(SKINR). The grant was intended to support research into the

interactions of hydrogen with palladium, nickel or platinum under

extreme conditions.

In March 2013 Graham K. Hubler, a nuclear physicist who worked for the

Naval Research Laboratory for 40 years, was named director.

One of the SKINR projects is to replicate a 1991 experiment in which a

professor associated with the project, Mark Prelas, says bursts of

millions of neutrons a second were recorded, which was stopped because

"his research account had been frozen". He claims that the new

experiment has already seen "neutron emissions at similar levels to the

1991 observation".

In May 2016, the United States House Committee on Armed Services, in its report on the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act, directed the Secretary of Defense

to "provide a briefing on the military utility of recent U.S.

industrial base LENR advancements to the House Committee on Armed

Services by September 22, 2016."

Italy

Since the

Fleischmann and Pons announcement, the Italian national agency for new

technologies, energy and sustainable economic development (ENEA) has funded Franco Scaramuzzi's research into whether excess heat can be measured from metals loaded with deuterium gas. Such research is distributed across ENEA departments, CNR laboratories, INFN,

universities and industrial laboratories in Italy, where the group

continues to try to achieve reliable reproducibility (i.e. getting the

phenomenon to happen in every cell, and inside a certain frame of time).

In 2006–2007, the ENEA started a research program which claimed to have

found excess power of up to 500 percent, and in 2009, ENEA hosted the

15th cold fusion conference.

Japan

Between 1992 and 1997, Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry sponsored a "New Hydrogen Energy (NHE)" program of US$20 million to research cold fusion.

Announcing the end of the program in 1997, the director and one-time

proponent of cold fusion research Hideo Ikegami stated "We couldn't

achieve what was first claimed in terms of cold fusion. (...) We can't

find any reason to propose more money for the coming year or for the

future."

In 1999 the Japan C-F Research Society was established to promote the

independent research into cold fusion that continued in Japan. The society holds annual meetings. Perhaps the most famous Japanese cold fusion researcher is Yoshiaki Arata,

from Osaka University, who claimed in a demonstration to produce excess

heat when deuterium gas was introduced into a cell containing a mixture

of palladium and zirconium oxide, a claim supported by fellow Japanese researcher Akira Kitamura of Kobe University and McKubre at SRI.

India

In the 1990s India stopped its research in cold fusion at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre because of the lack of consensus among mainstream scientists and the US denunciation of the research. Yet, in 2008, the National Institute of Advanced Studies recommended that the Indian government revive this research. Projects were commenced at Chennai's Indian Institute of Technology, the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre and the Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research. However, there is still skepticism among scientists and, for all practical purposes, research has stalled since the 1990s. A special section in the Indian multidisciplinary journal Current Science published 33 cold fusion papers in 2015 by major cold fusion researchers including several Indian researchers.

Reported results

A cold fusion experiment usually includes:

- a metal, such as palladium or nickel, in bulk, thin films or powder; and

- deuterium, hydrogen, or both, in the form of water, gas or plasma.

Electrolysis cells can be either open cell or closed cell. In open

cell systems, the electrolysis products, which are gaseous, are allowed

to leave the cell. In closed cell experiments, the products are

captured, for example by catalytically recombining the products in a

separate part of the experimental system. These experiments generally

strive for a steady state condition, with the electrolyte being replaced

periodically. There are also "heat-after-death" experiments, where the

evolution of heat is monitored after the electric current is turned off.

The most basic setup of a cold fusion cell consists of two

electrodes submerged in a solution containing palladium and heavy water.

The electrodes are then connected to a power source to transmit

electricity from one electrode to the other through the solution.

Even when anomalous heat is reported, it can take weeks for it to begin

to appear—this is known as the "loading time," the time required to

saturate the palladium electrode with hydrogen (see "Loading ratio"

section).

The Fleischmann and Pons early findings regarding helium, neutron

radiation and tritium were never replicated satisfactorily, and its

levels were too low for the claimed heat production and inconsistent

with each other.

Neutron radiation has been reported in cold fusion experiments at very

low levels using different kinds of detectors, but levels were too low,

close to background, and found too infrequently to provide useful

information about possible nuclear processes.

Excess heat and energy production

An excess heat observation is based on an energy balance.

Various sources of energy input and output are continuously measured.

Under normal conditions, the energy input can be matched to the energy

output to within experimental error. In experiments such as those run by

Fleischmann and Pons, an electrolysis cell operating steadily at one

temperature transitions to operating at a higher temperature with no

increase in applied current.

If the higher temperatures were real, and not an experimental artifact,

the energy balance would show an unaccounted term. In the Fleischmann

and Pons experiments, the rate of inferred excess heat generation was in

the range of 10–20% of total input, though this could not be reliably

replicated by most researchers. Researcher Nathan Lewis

discovered that the excess heat in Fleischmann and Pons's original

paper was not measured, but estimated from measurements that didn't have

any excess heat.

Unable to produce excess heat or neutrons, and with positive

experiments being plagued by errors and giving disparate results, most

researchers declared that heat production was not a real effect and

ceased working on the experiments.

In 1993, after their original report, Fleischmann reported

"heat-after-death" experiments—where excess heat was measured after the

electric current supplied to the electrolytic cell was turned off. This type of report has also become part of subsequent cold fusion claims.

Helium, heavy elements, and neutrons

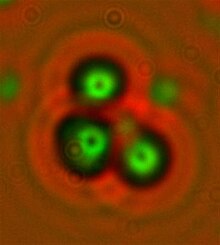

"Triple tracks" in a CR-39 plastic radiation detector claimed as evidence for neutron emission from palladium deuteride

Known instances of nuclear reactions, aside from producing energy, also produce nucleons

and particles on readily observable ballistic trajectories. In support

of their claim that nuclear reactions took place in their electrolytic

cells, Fleischmann and Pons reported a neutron flux of 4,000 neutrons per second, as well as detection of tritium. The classical branching ratio for previously known fusion reactions that produce tritium would predict, with 1 watt of power, the production of 1012 neutrons per second, levels that would have been fatal to the researchers. In 2009, Mosier-Boss et al. reported what they called the first scientific report of highly energetic neutrons, using CR-39 plastic radiation detectors, but the claims cannot be validated without a quantitative analysis of neutrons.

Several medium and heavy elements like calcium, titanium,

chromium, manganese, iron, cobalt, copper and zinc have been reported as

detected by several researchers, like Tadahiko Mizuno or George Miley. The report presented to the United States Department of Energy (DOE)

in 2004 indicated that deuterium-loaded foils could be used to detect

fusion reaction products and, although the reviewers found the evidence

presented to them as inconclusive, they indicated that those experiments

did not use state-of-the-art techniques.

In response to doubts about the lack of nuclear products, cold

fusion researchers have tried to capture and measure nuclear products

correlated with excess heat. Considerable attention has been given to measuring 4He production.

However, the reported levels are very near to background, so

contamination by trace amounts of helium normally present in the air

cannot be ruled out. In the report presented to the DOE in 2004, the

reviewers' opinion was divided on the evidence for 4He; with

the most negative reviews concluding that although the amounts detected

were above background levels, they were very close to them and therefore

could be caused by contamination from air.

One of the main criticisms of cold fusion was that

deuteron-deuteron fusion into helium was expected to result in the

production of gamma rays—which were not observed and were not observed in subsequent cold fusion experiments. Cold fusion researchers have since claimed to find X-rays, helium, neutrons and nuclear transmutations. Some researchers also claim to have found them using only light water and nickel cathodes.

The 2004 DOE panel expressed concerns about the poor quality of the

theoretical framework cold fusion proponents presented to account for

the lack of gamma rays.

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers in the field do not agree on a theory for cold fusion. One proposal considers that hydrogen and its isotopes can be absorbed in certain solids, including palladium hydride,

at high densities. This creates a high partial pressure, reducing the

average separation of hydrogen isotopes. However, the reduction in

separation is not enough by a factor of ten to create the fusion rates

claimed in the original experiment.

It was also proposed that a higher density of hydrogen inside the

palladium and a lower potential barrier could raise the possibility of

fusion at lower temperatures than expected from a simple application of Coulomb's law. Electron screening of the positive hydrogen nuclei by the negative electrons in the palladium lattice was suggested to the 2004 DOE commission, but the panel found the theoretical explanations not convincing and inconsistent with current physics theories.

Criticism

Criticism

of cold fusion claims generally take one of two forms: either pointing

out the theoretical implausibility that fusion reactions have occurred

in electrolysis setups or criticizing the excess heat measurements as

being spurious, erroneous, or due to poor methodology or controls. There

are a couple of reasons why known fusion reactions are an unlikely

explanation for the excess heat and associated cold fusion claims.

Repulsion forces

Because nuclei are all positively charged, they strongly repel one another. Normally, in the absence of a catalyst such as a muon, very high kinetic energies are required to overcome this charged repulsion.

Extrapolating from known fusion rates, the rate for uncatalyzed fusion

at room-temperature energy would be 50 orders of magnitude lower than

needed to account for the reported excess heat.

In muon-catalyzed fusion there are more fusions because the presence of

the muon causes deuterium nuclei to be 207 times closer than in

ordinary deuterium gas.

But deuterium nuclei inside a palladium lattice are further apart than

in deuterium gas, and there should be fewer fusion reactions, not more.

Paneth and Peters in the 1920s already knew that palladium can

absorb up to 900 times its own volume of hydrogen gas, storing it at

several thousands of times the atmospheric pressure. This led them to believe that they could increase the nuclear fusion rate by simply loading palladium rods with hydrogen gas.

Tandberg then tried the same experiment but used electrolysis to make

palladium absorb more deuterium and force the deuterium further together

inside the rods, thus anticipating the main elements of Fleischmann and

Pons' experiment.

They all hoped that pairs of hydrogen nuclei would fuse together to

form helium, which at the time was needed in Germany to fill zeppelins, but no evidence of helium or of increased fusion rate was ever found.

This was also the belief of geologist Palmer, who convinced

Steven Jones that the helium-3 occurring naturally in Earth perhaps came

from fusion involving hydrogen isotopes inside catalysts like nickel

and palladium.

This led their team in 1986 to independently make the same experimental

setup as Fleischmann and Pons (a palladium cathode submerged in heavy

water, absorbing deuterium via electrolysis). Fleischmann and Pons had much the same belief, but they calculated the pressure to be of 1027

atmospheres, when cold fusion experiments only achieve a loading ratio

of one to one, which only has between 10,000 and 20,000 atmospheres. John R. Huizenga says they had misinterpreted the Nernst equation,

leading them to believe that there was enough pressure to bring

deuterons so close to each other that there would be spontaneous

fusions.

Lack of expected reaction products

Conventional deuteron fusion is a two-step process, in which an unstable high-energy intermediary is formed:

Experiments have observed only three decay pathways for this excited-state nucleus, with the branching ratio showing the probability that any given intermediate follows a particular pathway. The products formed via these decay pathways are:

- 4He* → n + 3He + 3.3 MeV (ratio=50%)

- 4He* → p + 3H + 4.0 MeV (ratio=50%)

- 4He* → 4He + γ + 24 MeV (ratio=10−6)

Only about one in one million of the intermediaries decay along the

third pathway, making its products comparatively rare when compared to

the other paths. This result is consistent with the predictions of the Bohr model. If one watt (1 W = 1 J/s ; 1 J = 6.242 × 1018 eV = 6.242 × 1012 MeV since 1 eV = 1.602 × 10−19 joule) of nuclear power were produced from ~2.2575 × 1011 deuteron fusion individual reactions each second consistent with known branching ratios, the resulting neutron and tritium (3H) production would be easily measured. Some researchers reported detecting 4He

but without the expected neutron or tritium production; such a result

would require branching ratios strongly favouring the third pathway,

with the actual rates of the first two pathways lower by at least five

orders of magnitude than observations from other experiments, directly

contradicting both theoretically predicted and observed branching

probabilities. Those reports of 4He production did not include detection of gamma rays, which would require the third pathway to have been changed somehow so that gamma rays are no longer emitted.

The known rate of the decay process together with the inter-atomic spacing in a metallic crystal makes heat transfer of the 24 MeV excess energy into the host metal lattice prior to the intermediary's decay inexplicable in terms of conventional understandings of momentum and energy transfer, and even then there would be measurable levels of radiation. Also, experiments indicate that the ratios of deuterium fusion remain constant at different energies. In general, pressure and chemical environment only cause small changes to fusion ratios. An early explanation invoked the Oppenheimer–Phillips process at low energies, but its magnitude was too small to explain the altered ratios.

Setup of experiments

Cold fusion setups utilize an input power source (to ostensibly provide activation energy), a platinum group electrode, a deuterium or hydrogen source, a calorimeter,

and, at times, detectors to look for byproducts such as helium or

neutrons. Critics have variously taken issue with each of these aspects

and have asserted that there has not yet been a consistent reproduction

of claimed cold fusion results in either energy output or byproducts.

Some cold fusion researchers who claim that they can consistently

measure an excess heat effect have argued that the apparent lack of

reproducibility might be attributable to a lack of quality control in

the electrode metal or the amount of hydrogen or deuterium loaded in the

system. Critics have further taken issue with what they describe as

mistakes or errors of interpretation that cold fusion researchers have

made in calorimetry analyses and energy budgets.

Reproducibility

In

1989, after Fleischmann and Pons had made their claims, many research

groups tried to reproduce the Fleischmann-Pons experiment, without

success. A few other research groups, however, reported successful

reproductions of cold fusion during this time. In July 1989, an Indian

group from the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (P. K. Iyengar and M. Srinivasan) and in October 1989, John Bockris' group from Texas A&M University reported on the creation of tritium. In December 1990, professor Richard Oriani of the University of Minnesota reported excess heat.

Groups that did report successes found that some of their cells

were producing the effect, while other cells that were built exactly the

same and used the same materials were not producing the effect.

Researchers that continued to work on the topic have claimed that over

the years many successful replications have been made, but still have

problems getting reliable replications. Reproducibility

is one of the main principles of the scientific method, and its lack

led most physicists to believe that the few positive reports could be

attributed to experimental error. The DOE 2004 report said among its conclusions and recommendations:

"Ordinarily, new scientific discoveries are claimed to be consistent and reproducible; as a result, if the experiments are not complicated, the discovery can usually be confirmed or disproved in a few months. The claims of cold fusion, however, are unusual in that even the strongest proponents of cold fusion assert that the experiments, for unknown reasons, are not consistent and reproducible at the present time. (...) Internal inconsistencies and lack of predictability and reproducibility remain serious concerns. (...) The Panel recommends that the cold fusion research efforts in the area of heat production focus primarily on confirming or disproving reports of excess heat."

Loading ratio

Michael McKubre working on deuterium gas-based cold fusion cell used by SRI International

Cold fusion researchers (McKubre since 1994, ENEA in 2011)

have speculated that a cell that is loaded with a deuterium/palladium

ratio lower than 100% (or 1:1) will not produce excess heat.

Since most of the negative replications from 1989 to 1990 did not

report their ratios, this has been proposed as an explanation for failed

replications.

This loading ratio is hard to obtain, and some batches of palladium

never reach it because the pressure causes cracks in the palladium,

allowing the deuterium to escape. Fleischmann and Pons never disclosed the deuterium/palladium ratio achieved in their cells,

there are no longer any batches of the palladium used by Fleischmann

and Pons (because the supplier now uses a different manufacturing

process), and researchers still have problems finding batches of palladium that achieve heat production reliably.

Misinterpretation of data

Some

research groups initially reported that they had replicated the

Fleischmann and Pons results but later retracted their reports and

offered an alternative explanation for their original positive results. A

group at Georgia Tech found problems with their neutron detector, and Texas A&M discovered bad wiring in their thermometers. These retractions, combined with negative results from some famous laboratories, led most scientists to conclude, as early as 1989, that no positive result should be attributed to cold fusion.

Calorimetry errors

The calculation of excess heat in electrochemical cells involves certain assumptions. Errors in these assumptions have been offered as non-nuclear explanations for excess heat.

One assumption made by Fleischmann and Pons is that the

efficiency of electrolysis is nearly 100%, meaning nearly all the

electricity applied to the cell resulted in electrolysis of water, with

negligible resistive heating and substantially all the electrolysis product leaving the cell unchanged. This assumption gives the amount of energy expended converting liquid D2O into gaseous D2 and O2.

The efficiency of electrolysis is less than one if hydrogen and oxygen

recombine to a significant extent within the calorimeter. Several

researchers have described potential mechanisms by which this process

could occur and thereby account for excess heat in electrolysis

experiments.

Another assumption is that heat loss from the calorimeter

maintains the same relationship with measured temperature as found when

calibrating the calorimeter.

This assumption ceases to be accurate if the temperature distribution

within the cell becomes significantly altered from the condition under

which calibration measurements were made. This can happen, for example, if fluid circulation within the cell becomes significantly altered.

Recombination of hydrogen and oxygen within the calorimeter would also

alter the heat distribution and invalidate the calibration.

Publications

The ISI

identified cold fusion as the scientific topic with the largest number

of published papers in 1989, of all scientific disciplines. The Nobel Laureate Julian Schwinger

declared himself a supporter of cold fusion in the fall of 1989, after

much of the response to the initial reports had turned negative. He

tried to publish his theoretical paper "Cold Fusion: A Hypothesis" in Physical Review Letters, but the peer reviewers rejected it so harshly that he felt deeply insulted, and he resigned from the American Physical Society (publisher of PRL) in protest.

The number of papers sharply declined after 1990 because of two

simultaneous phenomena: first, scientists abandoned the field; second,

journal editors declined to review new papers. Consequently, cold fusion

fell off the ISI charts. Researchers who got negative results turned their backs on the field; those who continued to publish were simply ignored. A 1993 paper in Physics Letters A

was the last paper published by Fleischmann, and "one of the last

reports [by Fleischmann] to be formally challenged on technical grounds

by a cold fusion skeptic."

The Journal of Fusion Technology (FT) established a

permanent feature in 1990 for cold fusion papers, publishing over a

dozen papers per year and giving a mainstream outlet for cold fusion

researchers. When editor-in-chief George H. Miley retired in 2001, the journal stopped accepting new cold fusion papers.

This has been cited as an example of the importance of sympathetic

influential individuals to the publication of cold fusion papers in

certain journals.

The decline of publications in cold fusion has been described as a "failed information epidemic".

The sudden surge of supporters until roughly 50% of scientists support

the theory, followed by a decline until there is only a very small

number of supporters, has been described as a characteristic of pathological science.

The lack of a shared set of unifying concepts and techniques has

prevented the creation of a dense network of collaboration in the field;

researchers perform efforts in their own and in disparate directions,

making the transition to "normal" science more difficult.

Cold fusion reports continued to be published in a small cluster of specialized journals like Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Il Nuovo Cimento. Some papers also appeared in Journal of Physical Chemistry, Physics Letters A, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, and a number of Japanese and Russian journals of physics, chemistry, and engineering. Since 2005, Naturwissenschaften

has published cold fusion papers; in 2009, the journal named a cold

fusion researcher to its editorial board. In 2015 the Indian

multidisciplinary journal Current Science published a special section devoted entirely to cold fusion related papers.

In the 1990s, the groups that continued to research cold fusion

and their supporters established (non-peer-reviewed) periodicals such as

Fusion Facts, Cold Fusion Magazine, Infinite Energy Magazine and New Energy Times

to cover developments in cold fusion and other fringe claims in energy

production that were ignored in other venues. The internet has also

become a major means of communication and self-publication for CF

researchers.

Conferences

Cold

fusion researchers were for many years unable to get papers accepted at

scientific meetings, prompting the creation of their own conferences.

The first International Conference on Cold Fusion

(ICCF) was held in 1990, and has met every 12 to 18 months since.

Attendees at some of the early conferences were described as offering no

criticism to papers and presentations for fear of giving ammunition to

external critics, thus allowing the proliferation of crackpots and hampering the conduct of serious science. Critics and skeptics stopped attending these conferences, with the notable exception of Douglas Morrison, who died in 2001. With the founding in 2004 of the International Society for Condensed Matter Nuclear Science (ISCMNS), the conference was renamed the International Conference on Condensed Matter Nuclear Science – for reasons that are detailed in the subsequent research section above – but reverted to the old name in 2008. Cold fusion research is often referenced by proponents as "low-energy nuclear reactions", or LENR, but according to sociologist Bart Simon the "cold fusion" label continues to serve a social function in creating a collective identity for the field.

Since 2006, the American Physical Society

(APS) has included cold fusion sessions at their semiannual meetings,

clarifying that this does not imply a softening of skepticism. Since 2007, the American Chemical Society (ACS) meetings also include "invited symposium(s)" on cold fusion.

An ACS program chair said that without a proper forum the matter would

never be discussed and, "with the world facing an energy crisis, it is

worth exploring all possibilities."

On 22–25 March 2009, the American Chemical Society meeting

included a four-day symposium in conjunction with the 20th anniversary

of the announcement of cold fusion. Researchers working at the U.S.

Navy's Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center (SPAWAR) reported detection of energetic neutrons using a heavy water electrolysis setup and a CR-39 detector, a result previously published in Naturwissenschaften. The authors claim that these neutrons are indicative of nuclear reactions;

without quantitative analysis of the number, energy, and timing of the

neutrons and exclusion of other potential sources, this interpretation

is unlikely to find acceptance by the wider scientific community.

Patents

Although

details have not surfaced, it appears that the University of Utah

forced the 23 March 1989 Fleischmann and Pons announcement to establish

priority over the discovery and its patents before the joint publication

with Jones. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announced on 12 April 1989 that it had applied for its own patents based on theoretical work of one of its researchers, Peter L. Hagelstein, who had been sending papers to journals from 5 to 12 April.

On 2 December 1993 the University of Utah licensed all its cold fusion

patents to ENECO, a new company created to profit from cold fusion

discoveries, and in March 1998 it said that it would no longer defend its patents.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) now rejects patents claiming cold fusion. Esther Kepplinger, the deputy commissioner of patents in 2004, said that this was done using the same argument as with perpetual motion machines: that they do not work. Patent applications are required to show that the invention is "useful", and this utility is dependent on the invention's ability to function.

In general USPTO rejections on the sole grounds of the invention's

being "inoperative" are rare, since such rejections need to demonstrate

"proof of total incapacity",

and cases where those rejections are upheld in a Federal Court are even

rarer: nevertheless, in 2000, a rejection of a cold fusion patent was

appealed in a Federal Court and it was upheld, in part on the grounds

that the inventor was unable to establish the utility of the invention.

A U.S. patent might still be granted when given a different name to disassociate it from cold fusion,

though this strategy has had little success in the US: the same claims

that need to be patented can identify it with cold fusion, and most of

these patents cannot avoid mentioning Fleischmann and Pons' research due

to legal constraints, thus alerting the patent reviewer that it is a

cold-fusion-related patent.

David Voss said in 1999 that some patents that closely resemble cold

fusion processes, and that use materials used in cold fusion, have been

granted by the USPTO.

The inventor of three such patents had his applications initially

rejected when they were reviewed by experts in nuclear science; but then

he rewrote the patents to focus more on the electrochemical parts so

they would be reviewed instead by experts in electrochemistry, who

approved them.

When asked about the resemblance to cold fusion, the patent holder said

that it used nuclear processes involving "new nuclear physics"

unrelated to cold fusion.

Melvin Miles was granted in 2004 a patent for a cold fusion device, and

in 2007 he described his efforts to remove all instances of "cold

fusion" from the patent description to avoid having it rejected

outright.

At least one patent related to cold fusion has been granted by the European Patent Office.

A patent only legally prevents others from using or benefiting

from one's invention. However, the general public perceives a patent as a

stamp of approval, and a holder of three cold fusion patents said the

patents were very valuable and had helped in getting investments.

Cultural references

A 1990 Michael Winner film Bullseye!, starring Michael Caine and Roger Moore,

referenced the Fleischmann and Pons experiment. The film – a comedy –

concerned conmen trying to steal scientists' purported findings.

However, the film had a poor reception, described as "appallingly

unfunny".

In Undead Science, sociologist Bart Simon gives some

examples of cold fusion in popular culture, saying that some scientists

use cold fusion as a synonym for outrageous claims made with no

supporting proof, and courses of ethics in science give it as an example of pathological science. It has appeared as a joke in Murphy Brown and The Simpsons. It was adopted as a software product name Adobe ColdFusion and a brand of protein bars (Cold Fusion Foods). It has also appeared in advertising as a synonym for impossible science, for example a 1995 advertisement for Pepsi Max.

The plot of The Saint, a 1997 action-adventure film, parallels the story of Fleischmann and Pons, although with a different ending. The film might have affected the public perception of cold fusion, pushing it further into the science fiction realm.

"Final Exam", the 16th episode of season 4 of The Outer Limits,

depicts a student named Todtman who has invented a cold fusion weapon,

and attempts to use it as a tool for revenge on people who have wronged

him over the years. Despite the secret being lost with his death at the

end of the episode, it is implied that another student elsewhere is on a

similar track, and may well repeat Todtman's efforts.

In the DC's Legends of Tomorrow

episode "No Country for Old Dads," Ray Palmer theorizes that cold

fusion could repair the shattered Fire Totem, if it wasn't only

theoretical.

Damien Dahrk reveals that he assassinated a scientist in 1962 East

Berlin that developed a formula for cold fusion. Ray and Dahrk's

daughter Nora time travel from 2018 to 1962 in an attempt to rescue the

scientist from the younger version of Dahrk and/or retrieve the formula.