Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to think and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowledge, self-transcendence and non-attachment, and virtues such as ethics and benevolence.

Wisdom has been defined in many different ways, including several distinct approaches to assess the characteristics attributed to wisdom.

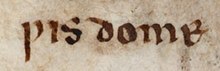

Definitions

The Oxford English Dictionary defines wisdom as "Capacity of judging rightly in matters relating to life and conduct; soundness of judgement in the choice of means and ends; sometimes, less strictly, sound sense, esp. in practical affairs: opp. to folly;" also "Knowledge (esp. of a high or abstruse kind); enlightenment, learning, erudition." Charles Haddon Spurgeon defined wisdom as "the right use of knowledge". Robert I. Sutton and Andrew Hargadon defined the "attitude of wisdom" as "acting with knowledge while doubting what one knows". Psycanics defines wisdom as "the ability to foresee the consequences of action" (allowing one to avoid negative consequences and produce the desired positive ones.) In social and psychological sciences, several distinct approaches to wisdom exist, with major advances made in the last two decades with respect to operationalization and measurement of wisdom as a psychological construct. Wisdom is the capacity to have foreknowledge of something, to know the consequences (both positive and negative) of all the available course of actions, and to yield or take the options with the most advantage either for present or future implication.

Mythological and philosophical perspectives

The ancient Greeks considered wisdom to be an important virtue, personified as the goddesses Metis and Athena. Metis was the first wife of Zeus, who, according to Hesiod's Theogony, had devoured her pregnant; Zeus earned the title of Mêtieta ("The Wise Counselor") after that, as Metis was the embodiment of wisdom, and he gave birth to Athena, who is said to have sprung from his head. Athena was portrayed as strong, fair, merciful, and chaste. Apollo was also considered a god of wisdom, designated as the conductor of the Muses (Musagetes), who were personifications of the sciences and of the inspired and poetic arts; According to Plato in his Cratylus, the name of Apollo could also mean "Ballon" (archer) and "Omopoulon" (unifier of poles [divine and earthly]), since this god was responsible for divine and true inspirations, thus considered an archer who was always right in healing and oracles: "he is an ever-darting archer". Apollo was considered the god who prophesied through the priestesses (Pythia) in the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), where the aphorism "know thyself" (gnōthi seauton) was inscribed (part of the wisdom of the Delphic maxims). He was contrasted with Hermes, who was related to the sciences and technical wisdom, and, in the first centuries after Christ, was associated with Thoth in an Egyptian syncretism, under the name Hermes Trimegistus. Greek tradition recorded the earliest introducers of wisdom in the Seven Sages of Greece.

To Socrates and Plato, philosophy was literally the love of wisdom (philo-sophia). This permeates Plato's dialogues; in The Republic the leaders of his proposed utopia are philosopher kings who understand the Form of the Good and possess the courage to act accordingly. Aristotle, in Metaphysics, defined wisdom as understanding why things are a certain way (causality), which is deeper than merely knowing things are a certain way. He was the first to make the distinction between phronesis and sophia.

According to Plato and Xenophon, the Pythia of the Delphic Oracle answered the question "who is the wisest man in Greece?" by stating Socrates was the wisest. According to Plato's Apology, Socrates decided to investigate the people who might be considered wiser than him, concluding they lacked true knowledge:

[…] οὗτος μὲν οἴεταί τι εἰδέναι οὐκ εἰδώς, ἐγὼ δέ, ὥσπερ οὖν οὐκ οἶδα, οὐδὲ οἴομαι [I am wiser than this man; for neither of us really knows anything fine and good, but this man thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas I, as I do not know anything, do not think I do either.]

— Apology to Socrates 21d

Thus it became popularly immortalized in the phrase "I know that I know nothing" that it is wise to recognize one's own ignorance and to value epistemic humility.

The ancient Romans also valued wisdom which was personified in Minerva, or Pallas. She also represents skillful knowledge and the virtues, especially chastity. Her symbol was the owl which is still a popular representation of wisdom, because it can see in darkness. She was said to be born from Jupiter's forehead.

Wisdom is also important within Christianity. Jesus emphasized it. Paul the Apostle, in his first epistle to the Corinthians, argued that there is both secular and divine wisdom, urging Christians to pursue the latter. Prudence, which is intimately related to wisdom, became one of the four cardinal virtues of Catholicism. The Christian philosopher Thomas Aquinas considered wisdom to be the "father" (i.e. the cause, measure, and form) of all virtues.

In Buddhist traditions, developing wisdom plays a central role where comprehensive guidance on how to develop wisdom is provided. In the Inuit tradition, developing wisdom was one of the aims of teaching. An Inuit Elder said that a person became wise when they could see what needed to be done and did it successfully without being told what to do.

In many cultures, the name for third molars, which are the last teeth to grow, is etymologically linked with wisdom, e.g., as in the English wisdom tooth. It has its nickname originated from the classical tradition, which in the Hippocratic writings has already been called sóphronistér (in Greek, related to the meaning of moderation or teaching a lesson), and in Latin dens sapientiae (wisdom tooth), since they appear at the age of maturity in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Educational perspectives

Public schools in the US have an approach to character education. Eighteenth century thinkers such as Benjamin Franklin, referred to this as training wisdom and virtue. Traditionally, schools share the responsibility to build character and wisdom along with parents and the community.

Nicholas Maxwell, a contemporary philosopher in the United Kingdom, advocates that academia ought to alter its focus from the acquisition of knowledge to seeking and promoting wisdom. This he defines as the capacity to realize what is of value in life, for oneself and others. He teaches that new knowledge and technological know-how increase our power to act. Without wisdom though, Maxwell claims this new knowledge may cause human harm as well as human good.

Psychological perspectives

Psychologists have begun to gather data on commonly held beliefs or folk theories about wisdom. Initial analyses indicate that although "there is an overlap of the implicit theory of wisdom with intelligence, perceptiveness, spirituality and shrewdness, it is evident that wisdom is an expertise in dealing with difficult questions of life and adaptation to the complex requirements."

Such implicit theories stand in contrast to the explicit theories and empirical research on resulting psychological processes underlying wisdom. Opinions on the exact psychological definitions of wisdom vary, but there is some consensus that critical to wisdom are certain meta-cognitive processes affording life reflection and judgment about critical life matters. These processes include recognizing the limits of one's own knowledge, acknowledging uncertainty and change, attention to context and the bigger picture, and integrating different perspectives of a situation. Cognitive scientists suggest that wisdom requires coordinating such reasoning processes, as they may provide insightful solutions for managing one's life. Notably, such reasoning is both theoretically and empirically distinct from general intelligence. Robert Sternberg has suggested that wisdom is not to be confused with general (fluid or crystallized) intelligence. In line with this idea, researchers have shown empirically that wise reasoning is distinct from IQ. Several more nuanced characterizations of wisdom are listed below.

Baltes and colleagues in Wisdom: its structure and function in regulating lifespan successful development defined wisdom as "the ability to deal with the contradictions of a specific situation and to assess the consequences of an action for themselves and for others. It is achieved when in a concrete situation, a balance between intrapersonal, inter- personal and institutional interests can be prepared". Balance itself appears to be a critical criterion of wisdom. Empirical research started to provide support to this idea, showing that wisdom-related reasoning is associated with achieving balance between intrapersonal and interpersonal interests when facing personal life challenges, and when setting goals for managing interpersonal conflicts.

Researchers in the field of positive psychology have defined wisdom as the coordination of "knowledge and experience" and "its deliberate use to improve well being." Under this definition, wisdom is further defined with the following facets:

- Problem Solving with self-knowledge and sustainable actions.

- Contextual sincerity to the circumstances with knowledge of its negative (or constraints) and positive aspects.

- Value based consistent actions with knowledge of diversity in ethical opinions.

- Tolerance towards uncertainty in life with unconditional acceptance.

- Empathy with oneself to understand one's own emotions (or to be emotionally oriented), morals...etc. and others feelings including the ability to see oneself as part of a larger whole.

This theoretical model has not been tested empirically, with an exception of a broad link between wisdom-related reasoning and well-being.

Grossmann and colleagues have synthesized prior psychological literature, indicating that in the face of ill-defined life situations wisdom involves certain cognitive processes affording unbiased, sound judgment: (i) intellectual humility or recognition of limits of own knowledge; (ii) appreciation of perspectives broader than the issue at hand; (iii) sensitivity to the possibility of change in social relations; and (iv) compromise or integration of different perspectives. Grossmann found that habitual speaking and thinking of oneself in the third person increases these characteristics, which means that such a habit makes a person wiser. Importantly, Grossmann highlights the fundamental role of contextual factors, including the role of culture, experiences, and social situations for understanding, development, and propensity of showing wisdom, with implications for training and educational practice. This situated account of wisdom ushered a novel phase of wisdom scholarship, using rigorous evidence-based methods to understand contextual factors affording sound judgment. For instance, Grossmann and Kross have identified a phenomenon they called "the Solomon's paradox" - wiser reflections on other people's problems as compared to one's own. It is named after King Solomon, the third leader of the Jewish Kingdom, who has shown a great deal of wisdom when making judgments about other people's dilemmas but lacked insight when it came to important decisions in his own life.

Empirical scientists have also begun to focus on the role of emotions in wisdom. Most researchers would agree that emotions and emotion regulation would be key to effectively managing the kinds of complex and arousing situations that would most call for wisdom. However, much empirical research has focused on the cognitive or meta-cognitive aspects of wisdom, assuming that an ability to reason through difficult situations would be paramount. Thus, although emotions would likely play a role in determining how wisdom plays out in real events and on reflecting on past events, only recently has empirical evidence started to provide robust evidence on how and when different emotions improve or harm a person's ability to deal wisely with complex events. One notable finding concerns the positive relationship between diversity of emotional experience and wise reasoning, irrespective of emotional intensity.

Measuring wisdom

Measurement of wisdom often depends on researcher's theoretical position about the nature of wisdom. A major distinction here concerning either viewing wisdom as a stable personality trait or rather as a context-bound process. The former approach often capitalizes on single-shot questionnaires. However, recent studies indicated that such single-shot questionnaires produce biased responses, which is antithetical to the wisdom construct and neglects the notion that wisdom is best understood in the contexts when it is most relevant, namely in complex life challenges. In contrast, the latter approach advocates for measuring wisdom-related features of cognition, motivation, and emotion on the level of a specific situation. Use of such state-level measures provides less biased responses as well as greater power in explaining meaningful psychological processes. Furthermore, a focus on the level of the situation has allowed wisdom researchers to develop a fuller understanding of the role of context itself for producing wisdom. Specifically, studies showed evidence of cross-cultural and within-cultural variability and systematic variability in reasoning wisely across contexts and in daily life.

Many, but not all, studies find that adults' self-ratings of perspective and wisdom do not depend on age. This belief stands in contrast to the popular notion that wisdom increases with age. The answer to the question of age-wisdom association depends on how one defines wisdom, and the methodological framework used to evaluate theoretical claims. Most recent work suggests that the answer to this question also depends on the degree of experience in a specific domain, with some contexts favoring older adults, others favoring younger adults, and some not differentiating age groups. Notably, rigorous longitudinal work is necessary to fully unpack the question of age-wisdom relationship and such work is still outstanding, with most studies relying on cross-sectional observations.

Sapience

Sapience is closely related to the term "sophia" often defined as "transcendent wisdom", "ultimate reality", or the ultimate truth of things. Sapiential perspective of wisdom is said to lie in the heart of every religion, where it is often acquired through intuitive knowing. This type of wisdom is described as going beyond mere practical wisdom and includes self-knowledge, interconnectedness, conditioned origination of mind-states and other deeper understandings of subjective experience. This type of wisdom can also lead to the ability of an individual to act with appropriate judgement, a broad understanding of situations and greater appreciation/compassion towards other living beings.

The word sapience is derived from the Latin sapientia, meaning "wisdom". The corresponding verb sapere has the original meaning of "to taste", hence "to perceive, to discern" and "to know"; its present participle sapiens was chosen by Carl Linnaeus for the Latin binomial for the human species, Homo sapiens.

Religious perspectives

Ancient Near East

In Mesopotamian religion and mythology, Enki, also known as Ea, was the God of wisdom and intelligence. Divine Wisdom allowed the provident designation of functions and the ordering of the cosmos, and it was achieved by humans in following me-s (in Sumerian, order, rite, righteousness), restoring the balance. In addition to hymns to Enki or Ea dating from the third millennium BC., there is amongst the clay tablets of Abu Salabikh from 2600 BC, considered as being the oldest dated texts, an "Hymn to Shamash", in which it is recorded written:

Wide is the courtyard of Shamash night chamber, (just as wide is the womb of) a wise pregnant woman! Sin, his warrior, wise one, heard of the offerings and came down to his fiesta. He is the father of the nation and the father of intelligence

The concept of Logos or manifest word of the divine thought, a concept also present in the philosophy and hymns of Egypt and Ancient Greece (being central to the thinker Heraclitus), and substantial in the Abrahamic traditions, seems to have been derived from Mesopotamian culture.

Sia represents the personification of perception and thoughtfulness in the traditional mythology adhered to in Ancient Egypt. Thoth, married to Maat (in ancient Egyptian, meaning order, righteousness, truth), was also important and regarded as a national introducer of wisdom.

Zoroastrianism

In the Avesta hymns traditionally attributed to Zoroaster, the Gathas, Ahura Mazda means "Lord" (Ahura) and "Wisdom" (Mazda), and it is the central deity who embodies goodness, being also called "Good Thought" (Vohu Manah). In Zoroastrianism in general, the order of the universe and morals is called Asha (in Avestan, truth, righteousness), which is determined by the designations of this omniscient Thought and also considered a deity emanating from Ahura (Amesha Spenta); it is related to another ahura deity, Spenta Mainyu (active Mentality). It says in Yazna 31:

To him shall the best befall, who, as one that knows, speaks to me Right's truthful word of Welfare and of Immortality; even the Dominion of Mazda which Good Thought shall increase for him. About which he in the beginning thus thought, "let the blessed realms be filled with Light", he it is that by his wisdom created Right.

Hebrew Bible and Judaism

The word wisdom (חכם) is mentioned 222 times in the Hebrew Bible. It was regarded as one of the highest virtues among the Israelites along with kindness (חסד) and justice (צדק). Both the books of Proverbs and Psalms urge readers to obtain and to increase in wisdom.

In the Hebrew Bible, wisdom is represented by Solomon, who asks God for wisdom in 2 Chronicles 1:10. Much of the Book of Proverbs, which is filled with wise sayings, is attributed to Solomon. In Proverbs 9:10, the fear of the Lord is called the beginning of wisdom. In Proverbs 1:20, there is also reference to wisdom personified in female form, "Wisdom calls aloud in the streets, she raises her voice in the marketplaces." In Proverbs 8:22–31, this personified wisdom is described as being present with God before creation began and even taking part in creation itself.

The Talmud teaches that a wise person is a person who can foresee the future. Nolad is a Hebrew word for "future," but also the Hebrew word for birth, so one rabbinic interpretation of the teaching is that a wise person is one who can foresee the consequences of his/her choices (i.e. can "see the future" that he/she "gives birth" to).

Hellenistic religion and Gnosticism

Christian theology

In Christian theology, "wisdom" (From Hebrew: חכמה transliteration: chokmâh pronounced: khok-maw', Greek: Sophia, Latin: Sapientia) describes an aspect of God, or the theological concept regarding the wisdom of God.

There is an oppositional element in Christian thought between secular wisdom and Godly wisdom. Paul the Apostle states that worldly wisdom thinks the claims of Christ to be foolishness. However, to those who are "on the path to salvation" Christ represents the wisdom of God. (1 Corinthians 1:17–31) Wisdom is considered one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit according to Anglican, Catholic, and Lutheran belief. 1 Corinthians 12:8–10 gives an alternate list of nine virtues, among which wisdom is one.

The book of Proverbs in the Old Testament of the Bible primarily focuses on wisdom, and was primarily written by one of the wisest kings according to Jewish history, King Solomon. Proverbs is found in the Old Testament section of the Bible and gives direction on how to handle various aspects of life; one's relationship with God, marriage, dealing with finances, work, friendships and persevering in difficult situations faced in life.

According to King Solomon, wisdom is gained from God, "For the Lord gives wisdom; from His mouth come knowledge and understanding" Proverbs 2:6. And through God's wise aide, one can have a better life: "He holds success in store for the upright, he is a shield to those whose walk is blameless, for he guards the course of the just and protects the way of his faithful ones" Proverbs 2:7-8. "Trust in the LORD with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding; in all your ways submit to him, and he will make your paths straight" Proverbs 3:5-6. Solomon basically states that with the wisdom one receives from God, one will be able to find success and happiness in life.

There are various verses in Proverbs that contain parallels of what God loves, which is wise, and what God does not love, which is foolish. For example, in the area of good and bad behaviour Proverbs states, "The way of the wicked is an abomination to the Lord, But He loves him who pursues righteousness (Proverbs 15:9). In relation to fairness and business it is stated that, "A false balance is an abomination to the Lord, But a just weight is His delight" (Proverbs 11:1; cf. 20:10,23). On the truth it is said, "Lying lips are an abomination to the Lord, But those who deal faithfully are His delight" (12:22; cf. 6:17,19). These are a few examples of what, according to Solomon, are good and wise in the eyes of God, or bad and foolish, and in doing these good and wise things, one becomes closer to God by living in an honorable and kind manner.

King Solomon continues his teachings of wisdom in the book of Ecclesiastes, which is considered one of the most depressing books of the Bible. Solomon discusses his exploration of the meaning of life and fulfillment, as he speaks of life's pleasures, work, and materialism, yet concludes that it is all meaningless. "'Meaningless! Meaningless!" says the Teacher [Solomon]. 'Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless'...For with much wisdom comes much sorrow, the more knowledge, the more grief" (Ecclesiastes 1:2,18) Solomon concludes that all life's pleasures and riches, and even wisdom, mean nothing if there is no relationship with God.

The book of James, written by the apostle James, is said to be the New Testament version of the book of Proverbs, in that it is another book that discusses wisdom. It reiterates Proverbs message of wisdom coming from God by stating, "If any of you lacks wisdom, you should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to you." James 1:5. James also explains how wisdom helps one acquire other forms of virtue, "But the wisdom that comes from heaven is first of all pure; then peace-loving, considerate, submissive, full of mercy and good fruit, impartial and sincere." James 3:17. In addition,through wisdom for living James focuses on using this God-given wisdom to perform acts of service to the less fortunate.

Apart from Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and James, other main books of wisdom in the Bible are Job, Psalms, and 1 and 2 Corinthians, which give lessons on gaining and using wisdom through difficult situations.

Indian religions

In the Indian traditions, wisdom can be called prajña or vijñana.

Developing wisdom is of central importance in Buddhist traditions, where the ultimate aim is often presented as "seeing things as they are" or as gaining a "penetrative understanding of all phenomena", which in turn is described as ultimately leading to the "complete freedom from suffering". In Buddhism, developing wisdom is accomplished through an understanding of what are known as the Four Noble Truths and by following the Noble Eightfold Path. This path lists mindfulness as one of eight required components for cultivating wisdom.

Buddhist scriptures teach that a wise person is usually endowed with good and maybe bodily conduct, and sometimes good verbal conduct, and good mental conduct.(AN 3:2) A wise person does actions that are unpleasant to do but give good results, and doesn't do actions that are pleasant to do but give bad results (AN 4:115). Wisdom is the antidote to the self-chosen poison of ignorance. The Buddha has much to say on the subject of wisdom including:

- He who arbitrates a case by force does not thereby become just (established in Dhamma). But the wise man is he who carefully discriminates between right and wrong.

- He who leads others by nonviolence, righteously and equitably, is indeed a guardian of justice, wise and righteous.

- One is not wise merely because he talks much. But he who is calm, free from hatred and fear, is verily called a wise man. By quietude alone one does not become a sage (muni) if he is foolish and ignorant. But he who, as if holding a pair of scales, takes the good and shuns the evil, is a wise man; he is indeed a muni by that very reason. He who understands both good and evil as they really are, is called a true sage.

To recover the original supreme wisdom of self-nature (Buddha-nature or Tathagata) covered by the self-imposed three dusty poisons (the kleshas: greed, anger, ignorance) Buddha taught to his students the threefold training by turning greed into generosity and discipline, anger into kindness and meditation, ignorance into wisdom. As the Sixth Patriarch of Chán Buddhism, Huineng, said in his Platform Sutra,"Mind without dispute is self-nature discipline, mind without disturbance is self-nature meditation, mind without ignorance is self-nature wisdom." In Mahayana and esoteric buddhist lineages, Mañjuśrī is considered as an embodiment of Buddha wisdom.

In Hinduism, wisdom is considered a state of mind and soul where a person achieves liberation.

The god of wisdom is Ganesha and the goddess of knowledge is Saraswati.

The Sanskrit verse to attain knowledge is:

असतो मा सद्गमय । Asatō mā sadgamaya

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय । tamasō mā jyōtirgamaya

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय । mr̥tyōrmā amr̥taṁ gamaya

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥ Om śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

- Br̥hadāraṇyakopaniṣat 1.3.28

- "Lead me from the unreal to the real.

- Lead me from darkness to light.

- Lead me from death to immortality.

- May there be peace, peace, and peace".

- Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.3.28.

Wisdom in Hinduism is knowing oneself as the truth, basis for the entire Creation, i.e., of Shristi. In other words, wisdom simply means a person with Self-awareness as the one who witnesses the entire creation in all its facets and forms. Further it means realization that an individual through right conduct and right living over an unspecified period comes to realize their true relationship with the creation and the Paramatma.

Islam

The Arabic term corresponding to Hebrew Chokmah is حكمة ḥikma. The term occurs a number of times in the Quran, notably in Sura 2:269: "He gives wisdom to whom He wills, and whoever has been given wisdom has certainly been given much good. And none will remember except those of understanding." (Quran 2:269). and Sura 22:46: "Have they not travelled in the land, and have they hearts wherewith to feel and ears wherewith to hear? For indeed it is not the eyes that grow blind, but it is the hearts, which are within the bosoms, that grow blind."Quran 22:46 Sura 6: 151: "Say: "Come, I will rehearse what Allah (God) hath (really) prohibited you from": Join not anything as equal with Him; be good to your parents; kill not your children on a plea of want;― We provide sustenance for you and for them;― come not nigh to shameful deeds, whether open or secret; take not life, which Allah hath made sacred, except by way of justice and law: thus doth He command you, that ye may learn wisdom" (Quran 6:151).

The Sufi philosopher Ibn Arabi considers al-Hakim ("The Wise") as one of the names of the Creator. Wisdom and truth, considered divine attributes, were concepts related and valued in the Islamic sciences and philosophy since their beginnings, and the first Arab philosopher, Al-Kindi says at the beginning of his book:

We must not be ashamed to admire the truth or to acquire it, from wherever it comes. Even if it should come from far-flung nations and foreign peoples, there is for the student of truth nothing more important than the truth, nor is the truth demeaned or diminished by the one who states or conveys it; no one is demeaned by the truth, rather all are ennobled by it.

— Al-Kindi, On First Philosophy

Chinese religion

The Buddhist term Prajñā was translated into Chinese as 智慧 (pinyin zhìhuì, characters 智 "knowledge" and 慧 "bright, intelligent").

According to the Doctrine of the Mean, Confucius said:

"Love of learning is akin to wisdom. To practice with vigor is akin to humanity. To know to be shameful is akin to courage (zhi, ren, yong.. three of Mengzi's sprouts of virtue)."

Compare this with the Confucian classic Great Learning, which begins with: "The Way of learning to be great consists in manifesting the clear character, loving the people, and abiding in the highest good." One can clearly see the correlation with the Roman virtue prudence, especially if one interprets "clear character" as "clear conscience". (From Chan's Sources of Chinese Philosophy).

In Taoism, wisdom is construed as adherence to the Three Treasures (Taoism): charity, simplicity, and humility. "He who knows other men is discerning [智]; he who knows himself is intelligent [明]." (知人者智,自知者明。Tao Te Ching 33)

Others

In Norse mythology, the god Odin is especially known for his wisdom, often acquired through various hardships and ordeals involving pain and self-sacrifice. In one instance he plucked out an eye and offered it to Mímir, guardian of the well of knowledge and wisdom, in return for a drink from the well. In another famous account, Odin hanged himself for nine nights from Yggdrasil, the World Tree that unites all the realms of existence, suffering from hunger and thirst and finally wounding himself with a spear until he gained the knowledge of runes for use in casting powerful magic. He was also able to acquire the mead of poetry from the giants, a drink of which could grant the power of a scholar or poet, for the benefit of gods and mortals alike.

In Baháʼí Faith scripture, "The essence of wisdom is the fear of God, the dread of His scourge and punishment, and the apprehension of His justice and decree." Wisdom is seen as a light, that casts away darkness, and "its dictates must be observed under all circumstances". One may obtain knowledge and wisdom through God, his Word, and his Divine Manifestation and the source of all learning is the knowledge of God.

In the Star Wars universe, wisdom is valued in the narrative of the films, in which George Lucas figured issues of spirituality and morals, recurrent in mythological and philosophical themes; one of his inspirations was Joseph Campbell's The Hero of a Thousand Faces. Master Yoda is generally considered a popular figure of wisdom, evoking the image of an "Oriental Monk", and he is frequently quoted, analogously to Chinese thinkers or Eastern sages in general. Psychologist D. W. Kreger's book "The Tao of Yoda" adapts the wisdom of the Tao Te Ching in relation to Yoda's thinking. Knowledge is canonically considered one of the pillars of the Jedi, which is also cited in the non-canon book The Jedi Path, and wisdom can serve as a tenet for Jediism. The Jedi Code also states: "Ignorance, yet knowledge." In a psychology populational study published by Grossmann and team in 2019, master Yoda is considered wiser than Spock, another fictional character (from the Star Trek series), due to his emodiversity trait, which was positively associated to wise reasoning in people: "Yoda embraces his emotions and aims to achieve a balance between them. Yoda is known to be emotionally expressive, to share a good joke with others, but also to recognize sorrow and his past mistakes".