In geometry, a Cartesian coordinate system (UK: /kɑːrˈtiːzjən/, US: /kɑːrˈtiːʒən/) in a plane is a coordinate system that specifies each point uniquely by a pair of real numbers called coordinates, which are the signed distances to the point from two fixed perpendicular oriented lines, called coordinate lines, coordinate axes or just axes (plural of axis) of the system. The point where the axes meet is called the origin and has (0, 0) as coordinates. The axes directions represent an orthogonal basis. The combination of origin and basis forms a coordinate frame called the Cartesian frame.

Similarly, the position of any point in three-dimensional space can be specified by three Cartesian coordinates, which are the signed distances from the point to three mutually perpendicular planes. More generally, n Cartesian coordinates specify the point in an n-dimensional Euclidean space for any dimension n. These coordinates are the signed distances from the point to n mutually perpendicular fixed hyperplanes.

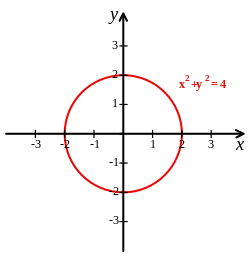

Cartesian coordinates are named for René Descartes, whose invention of them in the 17th century revolutionized mathematics by allowing the expression of problems of geometry in terms of algebra and calculus. Using the Cartesian coordinate system, geometric shapes (such as curves) can be described by equations involving the coordinates of points of the shape. For example, a circle of radius 2, centered at the origin of the plane, may be described as the set of all points whose coordinates x and y satisfy the equation x2 + y2 = 4; the area, the perimeter and the tangent line at any point can be computed from this equation by using integrals and derivatives, in a way that can be applied to any curve.

Cartesian coordinates are the foundation of analytic geometry, and provide enlightening geometric interpretations for many other branches of mathematics, such as linear algebra, complex analysis, differential geometry, multivariate calculus, group theory and more. A familiar example is the concept of the graph of a function. Cartesian coordinates are also essential tools for most applied disciplines that deal with geometry, including astronomy, physics, engineering and many more. They are the most common coordinate system used in computer graphics, computer-aided geometric design and other geometry-related data processing.

History

The adjective Cartesian refers to the French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes, who published this idea in 1637 while he was resident in the Netherlands. It was independently discovered by Pierre de Fermat, who also worked in three dimensions, although Fermat did not publish the discovery. The French cleric Nicole Oresme used constructions similar to Cartesian coordinates well before the time of Descartes and Fermat.

Both Descartes and Fermat used a single axis in their treatments and have a variable length measured in reference to this axis. The concept of using a pair of axes was introduced later, after Descartes' La Géométrie was translated into Latin in 1649 by Frans van Schooten and his students. These commentators introduced several concepts while trying to clarify the ideas contained in Descartes's work.

The development of the Cartesian coordinate system would play a fundamental role in the development of the calculus by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The two-coordinate description of the plane was later generalized into the concept of vector spaces.

Many other coordinate systems have been developed since Descartes, such as the polar coordinates for the plane, and the spherical and cylindrical coordinates for three-dimensional space.

Description

One dimension

An affine line with a chosen Cartesian coordinate system is called a number line. Every point on the line has a real-number coordinate, and every real number represents some point on the line.

There are two degrees of freedom in the choice of Cartesian coordinate system for a line, which can be specified by choosing two distinct points along the line and assigning them to two distinct real numbers (most commonly zero and one). Other points can then be uniquely assigned to numbers by linear interpolation. Equivalently, one point can be assigned to a specific real number, for instance an origin point corresponding to zero, and an oriented length along the line can be chosen as a unit, with the orientation indicating the correspondence between directions along the line and positive or negative numbers. Each point corresponds to its signed distance from the origin (a number with an absolute value equal to the distance and a + or − sign chosen based on direction).

A geometric transformation of the line can be represented by a function of a real variable, for example translation of the line corresponds to addition, and scaling the line corresponds to multiplication. Any two Cartesian coordinate systems on the line can be related to each-other by a linear function (function of the form ) taking a specific point's coordinate in one system to its coordinate in the other system. Choosing a coordinate system for each of two different lines establishes an affine map from one line to the other taking each point on one line to the point on the other line with the same coordinate.

Two dimensions

A Cartesian coordinate system in two dimensions (also called a rectangular coordinate system or an orthogonal coordinate system) is defined by an ordered pair of perpendicular lines (axes), a single unit of length for both axes, and an orientation for each axis. The point where the axes meet is taken as the origin for both, thus turning each axis into a number line. For any point P, a line is drawn through P perpendicular to each axis, and the position where it meets the axis is interpreted as a number. The two numbers, in that chosen order, are the Cartesian coordinates of P. The reverse construction allows one to determine the point P given its coordinates.

The first and second coordinates are called the abscissa and the ordinate of P, respectively; and the point where the axes meet is called the origin of the coordinate system. The coordinates are usually written as two numbers in parentheses, in that order, separated by a comma, as in (3, −10.5). Thus the origin has coordinates (0, 0), and the points on the positive half-axes, one unit away from the origin, have coordinates (1, 0) and (0, 1).

In mathematics, physics, and engineering, the first axis is usually defined or depicted as horizontal and oriented to the right, and the second axis is vertical and oriented upwards. (However, in some computer graphics contexts, the ordinate axis may be oriented downwards.) The origin is often labeled O, and the two coordinates are often denoted by the letters X and Y, or x and y. The axes may then be referred to as the X-axis and Y-axis. The choices of letters come from the original convention, which is to use the latter part of the alphabet to indicate unknown values. The first part of the alphabet was used to designate known values.

A Euclidean plane with a chosen Cartesian coordinate system is called a Cartesian plane. In a Cartesian plane, one can define canonical representatives of certain geometric figures, such as the unit circle (with radius equal to the length unit, and center at the origin), the unit square (whose diagonal has endpoints at (0, 0) and (1, 1)), the unit hyperbola, and so on.

The two axes divide the plane into four right angles, called quadrants. The quadrants may be named or numbered in various ways, but the quadrant where all coordinates are positive is usually called the first quadrant.

If the coordinates of a point are (x, y), then its distances from the X-axis and from the Y-axis are |y| and |x|, respectively; where | · | denotes the absolute value of a number.

Three dimensions

A Cartesian coordinate system for a three-dimensional space consists of an ordered triplet of lines (the axes) that go through a common point (the origin), and are pair-wise perpendicular; an orientation for each axis; and a single unit of length for all three axes. As in the two-dimensional case, each axis becomes a number line. For any point P of space, one considers a plane through P perpendicular to each coordinate axis, and interprets the point where that plane cuts the axis as a number. The Cartesian coordinates of P are those three numbers, in the chosen order. The reverse construction determines the point P given its three coordinates.

Alternatively, each coordinate of a point P can be taken as the distance from P to the plane defined by the other two axes, with the sign determined by the orientation of the corresponding axis.

Each pair of axes defines a coordinate plane. These planes divide space into eight octants. The octants are:

The coordinates are usually written as three numbers (or algebraic formulas) surrounded by parentheses and separated by commas, as in (3, −2.5, 1) or (t, u + v, π/2). Thus, the origin has coordinates (0, 0, 0), and the unit points on the three axes are (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), and (0, 0, 1).

Standard names for the coordinates in the three axes are abscissa, ordinate and applicate. The coordinates are often denoted by the letters x, y, and z. The axes may then be referred to as the x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis, respectively. Then the coordinate planes can be referred to as the xy-plane, yz-plane, and xz-plane.

In mathematics, physics, and engineering contexts, the first two axes are often defined or depicted as horizontal, with the third axis pointing up. In that case the third coordinate may be called height or altitude. The orientation is usually chosen so that the 90-degree angle from the first axis to the second axis looks counter-clockwise when seen from the point (0, 0, 1); a convention that is commonly called the right-hand rule.

Higher dimensions

Since Cartesian coordinates are unique and non-ambiguous, the points of a Cartesian plane can be identified with pairs of real numbers; that is, with the Cartesian product , where is the set of all real numbers. In the same way, the points in any Euclidean space of dimension n be identified with the tuples (lists) of n real numbers; that is, with the Cartesian product .

Generalizations

The concept of Cartesian coordinates generalizes to allow axes that are not perpendicular to each other, and/or different units along each axis. In that case, each coordinate is obtained by projecting the point onto one axis along a direction that is parallel to the other axis (or, in general, to the hyperplane defined by all the other axes). In such an oblique coordinate system the computations of distances and angles must be modified from that in standard Cartesian systems, and many standard formulas (such as the Pythagorean formula for the distance) do not hold (see affine plane).

Notations and conventions

The Cartesian coordinates of a point are usually written in parentheses and separated by commas, as in (10, 5) or (3, 5, 7). The origin is often labelled with the capital letter O. In analytic geometry, unknown or generic coordinates are often denoted by the letters (x, y) in the plane, and (x, y, z) in three-dimensional space. This custom comes from a convention of algebra, which uses letters near the end of the alphabet for unknown values (such as the coordinates of points in many geometric problems), and letters near the beginning for given quantities.

These conventional names are often used in other domains, such as physics and engineering, although other letters may be used. For example, in a graph showing how a pressure varies with time, the graph coordinates may be denoted p and t. Each axis is usually named after the coordinate which is measured along it; so one says the x-axis, the y-axis, the t-axis, etc.

Another common convention for coordinate naming is to use subscripts, as (x1, x2, ..., xn) for the n coordinates in an n-dimensional space, especially when n is greater than 3 or unspecified. Some authors prefer the numbering (x0, x1, ..., xn−1). These notations are especially advantageous in computer programming: by storing the coordinates of a point as an array, instead of a record, the subscript can serve to index the coordinates.

In mathematical illustrations of two-dimensional Cartesian systems, the first coordinate (traditionally called the abscissa) is measured along a horizontal axis, oriented from left to right. The second coordinate (the ordinate) is then measured along a vertical axis, usually oriented from bottom to top. Young children learning the Cartesian system, commonly learn the order to read the values before cementing the x-, y-, and z-axis concepts, by starting with 2D mnemonics (for example, 'Walk along the hall then up the stairs' akin to straight across the x-axis then up vertically along the y-axis).

Computer graphics and image processing, however, often use a coordinate system with the y-axis oriented downwards on the computer display. This convention developed in the 1960s (or earlier) from the way that images were originally stored in display buffers.

For three-dimensional systems, a convention is to portray the xy-plane horizontally, with the z-axis added to represent height (positive up). Furthermore, there is a convention to orient the x-axis toward the viewer, biased either to the right or left. If a diagram (3D projection or 2D perspective drawing) shows the x- and y-axis horizontally and vertically, respectively, then the z-axis should be shown pointing "out of the page" towards the viewer or camera. In such a 2D diagram of a 3D coordinate system, the z-axis would appear as a line or ray pointing down and to the left or down and to the right, depending on the presumed viewer or camera perspective. In any diagram or display, the orientation of the three axes, as a whole, is arbitrary. However, the orientation of the axes relative to each other should always comply with the right-hand rule, unless specifically stated otherwise. All laws of physics and math assume this right-handedness, which ensures consistency.

For 3D diagrams, the names "abscissa" and "ordinate" are rarely used for x and y, respectively. When they are, the z-coordinate is sometimes called the applicate. The words abscissa, ordinate and applicate are sometimes used to refer to coordinate axes rather than the coordinate values.

Quadrants and octants

The axes of a two-dimensional Cartesian system divide the plane into four infinite regions, called quadrants, each bounded by two half-axes. These are often numbered from 1st to 4th and denoted by Roman numerals: I (where the coordinates both have positive signs), II (where the abscissa is negative − and the ordinate is positive +), III (where both the abscissa and the ordinate are −), and IV (abscissa +, ordinate −). When the axes are drawn according to the mathematical custom, the numbering goes counter-clockwise starting from the upper right ("north-east") quadrant.

Similarly, a three-dimensional Cartesian system defines a division of space into eight regions or octants, according to the signs of the coordinates of the points. The convention used for naming a specific octant is to list its signs; for example, (+ + +) or (− + −). The generalization of the quadrant and octant to an arbitrary number of dimensions is the orthant, and a similar naming system applies.

Cartesian formulae for the plane

Distance between two points

The Euclidean distance between two points of the plane with Cartesian coordinates and is

This is the Cartesian version of Pythagoras's theorem. In three-dimensional space, the distance between points and is

which can be obtained by two consecutive applications of Pythagoras' theorem.

Euclidean transformations

The Euclidean transformations or Euclidean motions are the (bijective) mappings of points of the Euclidean plane to themselves which preserve distances between points. There are four types of these mappings (also called isometries): translations, rotations, reflections and glide reflections.

Translation

Translating a set of points of the plane, preserving the distances and directions between them, is equivalent to adding a fixed pair of numbers (a, b) to the Cartesian coordinates of every point in the set. That is, if the original coordinates of a point are (x, y), after the translation they will be

Rotation

To rotate a figure counterclockwise around the origin by some angle is equivalent to replacing every point with coordinates (x,y) by the point with coordinates (x',y'), where

Thus:

Reflection

If (x, y) are the Cartesian coordinates of a point, then (−x, y) are the coordinates of its reflection across the second coordinate axis (the y-axis), as if that line were a mirror. Likewise, (x, −y) are the coordinates of its reflection across the first coordinate axis (the x-axis). In more generality, reflection across a line through the origin making an angle with the x-axis, is equivalent to replacing every point with coordinates (x, y) by the point with coordinates (x′,y′), where

Thus:

Glide reflection

A glide reflection is the composition of a reflection across a line followed by a translation in the direction of that line. It can be seen that the order of these operations does not matter (the translation can come first, followed by the reflection).

General matrix form of the transformations

All affine transformations of the plane can be described in a uniform way by using matrices. For this purpose, the coordinates of a point are commonly represented as the column matrix The result of applying an affine transformation to a point is given by the formula where is a 2×2 matrix and is a column matrix. That is,

Among the affine transformations, the Euclidean transformations are characterized by the fact that the matrix is orthogonal; that is, its columns are orthogonal vectors of Euclidean norm one, or, explicitly, and

This is equivalent to saying that A times its transpose is the identity matrix. If these conditions do not hold, the formula describes a more general affine transformation.

The transformation is a translation if and only if A is the identity matrix. The transformation is a rotation around some point if and only if A is a rotation matrix, meaning that it is orthogonal and

A reflection or glide reflection is obtained when,

Assuming that translations are not used (that is, ) transformations can be composed by simply multiplying the associated transformation matrices. In the general case, it is useful to use the augmented matrix of the transformation; that is, to rewrite the transformation formula where With this trick, the composition of affine transformations is obtained by multiplying the augmented matrices.

Affine transformation

Affine transformations of the Euclidean plane are transformations that map lines to lines, but may change distances and angles. As said in the preceding section, they can be represented with augmented matrices:

The Euclidean transformations are the affine transformations such that the 2×2 matrix of the is orthogonal.

The augmented matrix that represents the composition of two affine transformations is obtained by multiplying their augmented matrices.

Some affine transformations that are not Euclidean transformations have received specific names.

Scaling

An example of an affine transformation which is not Euclidean is given by scaling. To make a figure larger or smaller is equivalent to multiplying the Cartesian coordinates of every point by the same positive number m. If (x, y) are the coordinates of a point on the original figure, the corresponding point on the scaled figure has coordinates

If m is greater than 1, the figure becomes larger; if m is between 0 and 1, it becomes smaller.

Shearing

A shearing transformation will push the top of a square sideways to form a parallelogram. Horizontal shearing is defined by:

Shearing can also be applied vertically:

Orientation and handedness

In two dimensions

Fixing or choosing the x-axis determines the y-axis up to direction. Namely, the y-axis is necessarily the perpendicular to the x-axis through the point marked 0 on the x-axis. But there is a choice of which of the two half lines on the perpendicular to designate as positive and which as negative. Each of these two choices determines a different orientation (also called handedness) of the Cartesian plane.

The usual way of orienting the plane, with the positive x-axis pointing right and the positive y-axis pointing up (and the x-axis being the "first" and the y-axis the "second" axis), is considered the positive or standard orientation, also called the right-handed orientation.

A commonly used mnemonic for defining the positive orientation is the right-hand rule. Placing a somewhat closed right hand on the plane with the thumb pointing up, the fingers point from the x-axis to the y-axis, in a positively oriented coordinate system.

The other way of orienting the plane is following the left-hand rule, placing the left hand on the plane with the thumb pointing up.

When pointing the thumb away from the origin along an axis towards positive, the curvature of the fingers indicates a positive rotation along that axis.

Regardless of the rule used to orient the plane, rotating the coordinate system will preserve the orientation. Switching any one axis will reverse the orientation, but switching both will leave the orientation unchanged.

In three dimensions

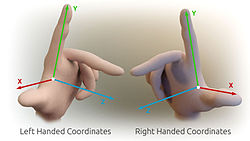

Once the x- and y-axes are specified, they determine the line along which the z-axis should lie, but there are two possible orientations for this line. The two possible coordinate systems which result are called 'right-handed' and 'left-handed'. The standard orientation, where the xy-plane is horizontal and the z-axis points up (and the x- and the y-axis form a positively oriented two-dimensional coordinate system in the xy-plane if observed from above the xy-plane) is called right-handed or positive.

The name derives from the right-hand rule. If the index finger of the right hand is pointed forward, the middle finger bent inward at a right angle to it, and the thumb placed at a right angle to both, the three fingers indicate the relative orientation of the x-, y-, and z-axes in a right-handed system. The thumb indicates the x-axis, the index finger the y-axis and the middle finger the z-axis. Conversely, if the same is done with the left hand, a left-handed system results.

Figure 7 depicts a left and a right-handed coordinate system. Because a three-dimensional object is represented on the two-dimensional screen, distortion and ambiguity result. The axis pointing downward (and to the right) is also meant to point towards the observer, whereas the "middle"-axis is meant to point away from the observer. The red circle is parallel to the horizontal xy-plane and indicates rotation from the x-axis to the y-axis (in both cases). Hence the red arrow passes in front of the z-axis.

Figure 8 is another attempt at depicting a right-handed coordinate system. Again, there is an ambiguity caused by projecting the three-dimensional coordinate system into the plane. Many observers see Figure 8 as "flipping in and out" between a convex cube and a concave "corner". This corresponds to the two possible orientations of the space. Seeing the figure as convex gives a left-handed coordinate system. Thus the "correct" way to view Figure 8 is to imagine the x-axis as pointing towards the observer and thus seeing a concave corner.

Representing a vector in the standard basis

A point in space in a Cartesian coordinate system may also be represented by a position vector, which can be thought of as an arrow pointing from the origin of the coordinate system to the point. If the coordinates represent spatial positions (displacements), it is common to represent the vector from the origin to the point of interest as . In two dimensions, the vector from the origin to the point with Cartesian coordinates (x, y) can be written as:

where and are unit vectors in the direction of the x-axis and y-axis respectively, generally referred to as the standard basis (in some application areas these may also be referred to as versors). Similarly, in three dimensions, the vector from the origin to the point with Cartesian coordinates can be written as:

where and

There is no natural interpretation of multiplying vectors to obtain another vector that works in all dimensions, however there is a way to use complex numbers to provide such a multiplication. In a two-dimensional cartesian plane, identify the point with coordinates (x, y) with the complex number z = x + iy. Here, i is the imaginary unit and is identified with the point with coordinates (0, 1), so it is not the unit vector in the direction of the x-axis. Since the complex numbers can be multiplied giving another complex number, this identification provides a means to "multiply" vectors. In a three-dimensional cartesian space a similar identification can be made with a subset of the quaternions.