Neuroscience of free will, a part of neurophilosophy, is the study of topics related to free will (volition and sense of agency) using neuroscience, and the analysis of how findings from such studies may impact the free will debate.

As it has become possible to study the living human brain, researchers have begun to watch neural decision-making processes at work. Studies have revealed unexpected things about human agency, moral responsibility, and consciousness in general. One of the pioneering studies in this domain was conducted by Benjamin Libet and colleagues in 1983 and has been the foundation of many studies in the years since. Other studies have attempted to predict participant actions before they make them, explore how we know we are responsible for voluntary movements as opposed to being moved by an external force, or how the role of consciousness in decision making may differ depending on the type of decision being made.

The field remains highly controversial. The significance of findings, their meaning, and what conclusions may be drawn from them is a matter of intense debate. The precise role of consciousness in decision making and how that role may differ across types of decisions remains unclear.

Philosophers like Daniel Dennett or Alfred Mele consider the language used by researchers. They explain that "free will" means many different things to different people (e.g. some notions of free will believe we need the dualistic values of both hard determinism and compatibilism, some not). Dennett insists that many important and common conceptions of "free will" are compatible with the emerging evidence from neuroscience.

Overview

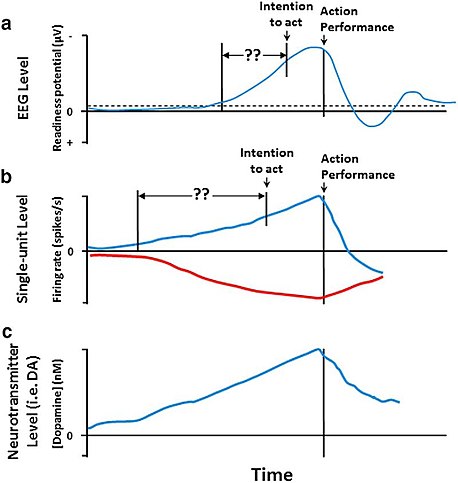

...the current work is in broad agreement with a general trend in neuroscience of volition: although we may experience that our conscious decisions and thoughts cause our actions, these experiences are in fact based on readouts of brain activity in a network of brain areas that control voluntary action... It is clearly wrong to think of [feeling of willing something as a prior intention, located at the very earliest moment of decision in an extended action chain. Rather, W seems to mark an intention-in-action, quite closely linked to action execution.

Patrick Haggard discussing an in-depth experiment by Itzhak Fried

The neuroscience of free will encompasses two main fields of study: volition and agency. Volition, the study of voluntary actions, is difficult to define. If we consider human actions as lying along a spectrum of our involvement in initiating the actions, then reflexes would be on one end, and fully voluntary actions would be on the other. How these actions are initiated and consciousness’ role in producing them is a major area of study in volition. Agency is the capacity of an actor to act in a given environment that has been debated since the beginning of philosophy. Within the neuroscience of free will, the sense of agency—the subjective awareness of initiating, executing, and controlling one's volitional actions—is usually what is studied.

One significant finding of modern studies is that a person's brain seems to commit to certain decisions before the person becomes aware of having made them. Researchers have found delays of about half a second or more (discussed in sections below). With contemporary brain scanning technology, scientists in 2008 were able to predict with 60% accuracy whether 12 subjects would press a button with their left or right hand up to 10 seconds before the subject became aware of having made that choice.[6] These and other findings have led some scientists, like Patrick Haggard, to reject some definitions of "free will".

To be clear, it is very unlikely that a single study could disprove all definitions of free will. Definitions of free will can vary wildly, and each must be considered separately in light of existing empirical evidence. There have also been a number of problems regarding studies of free will. Particularly in earlier studies, research relied on self-reported measures of conscious awareness, but introspective estimates of event timing were found to be biased or inaccurate in some cases. There is no agreed-upon measure of brain activity corresponding to conscious generation of intentions, choices, or decisions, making studying processes related to consciousness difficult. The conclusions drawn from measurements that have been made are debatable too, as they don't necessarily tell, for example, what a sudden dip in the readings represents. Such a dip might have nothing to do with unconscious decision because many other mental processes are going on while performing the task. Although early studies mainly used electroencephalography, more recent studies have used fMRI, single-neuron recordings, and other measures. Researcher Itzhak Fried says that available studies do at least suggest that consciousness comes in a later stage of decision making than previously expected – challenging any versions of "free will" where intention occurs at the beginning of the human decision process.

Free will as illusion

It is quite likely that a large range of cognitive operations are necessary to freely press a button. Research at least suggests that our conscious self does not initiate all behavior. Instead, the conscious self is somehow alerted to a given behavior that the rest of the brain and body are already planning and performing. These findings do not forbid conscious experience from playing some moderating role, although it is also possible that some form of unconscious process is what is causing modification in our behavioral response. Unconscious processes may play a larger role in behavior than previously thought.

It may be possible, then, that our intuitions about the role of our conscious "intentions" have led us astray; it may be the case that we have confused correlation with causation by believing that conscious awareness necessarily causes the body's movement. This possibility is bolstered by findings in neurostimulation, brain damage, but also research into introspection illusions. Such illusions show that humans do not have full access to various internal processes. The discovery that humans possess a determined will would have implications for moral responsibility or lack thereof. Neuroscientist and author Sam Harris believes that we are mistaken in believing the intuitive idea that intention initiates actions. In fact, Harris is even critical of the idea that free will is "intuitive": he says careful introspection can cast doubt on free will. Harris argues: "Thoughts simply arise in the brain. What else could they do? The truth about us is even stranger than we may suppose: The illusion of free will is itself an illusion". Neuroscientist Walter Jackson Freeman III, nevertheless, talks about the power of even unconscious systems and actions to change the world according to our intentions. He writes: "our intentional actions continually flow into the world, changing the world and the relations of our bodies to it. This dynamic system is the self in each of us, it is the agency in charge, not our awareness, which is constantly trying to keep up with what we do." To Freeman, the power of intention and action can be independent of awareness.

An important distinction to make is the difference between proximal and distal intentions. Proximal intentions are immediate in the sense that they are about acting now. For instance, a decision to raise a hand now or press a button now, as in Libet-style experiments. Distal intentions are delayed in the sense that they are about acting at a later point in time. For instance, deciding to go to the store later. Research has mostly focused on proximal intentions; however, it is unclear to what degree findings will generalize from one sort of intention to the other.

Relevance of scientific research

Some thinkers like neuroscientist and philosopher Adina Roskies think that these studies can still only show, unsurprisingly, that physical factors in the brain are involved before decision making. In contrast, Haggard believes that "We feel we choose, but we don't". Researcher John-Dylan Haynes adds: "How can I call a will 'mine' if I don't even know when it occurred and what it has decided to do?". Philosophers Walter Glannon and Alfred Mele think that some scientists are getting the science right, but misrepresenting modern philosophers. This is mainly because "free will" can mean many things: it is unclear what someone means when they say "free will does not exist". Mele and Glannon say that the available research is more evidence against any dualistic notions of free will – but that is an "easy target for neuroscientists to knock down". Mele says that most discussions of free will are now in materialistic terms. In these cases, "free will" means something more like "not coerced" or that "the person could have done otherwise at the last moment". The existence of these types of free will is debatable. Mele agrees, however, that science will continue to reveal critical details about what goes on in the brain during decision making.

[Some senses of free will] are compatible with what we are learning from science... If only that was what scientists were telling people. But scientists, especially in the last few years, have been on a rampage – writing ill-considered public pronouncements about free will which... verge on social irresponsibility.

Daniel Dennett discussing science and free will

This issue may be controversial for good reason: there is evidence to suggest that people normally associate a belief in free will with their ability to affect their lives. Philosopher Daniel Dennett, author of Elbow Room and a supporter of deterministic free will, believes that scientists risk making a serious mistake. He says that there are types of free will that are incompatible with modern science, but he says that those kinds of free will are not worth wanting. Other types of "free will" are pivotal to people's sense of responsibility and purpose (see also "believing in free will"), and many of these types are actually compatible with modern science.

The other studies described below have only just begun to shed light on the role that consciousness plays in actions, and it is too early to draw very strong conclusions about certain kinds of "free will". It is worth noting that such experiments so far have dealt only with free-will decisions made in short time frames (seconds) and may not have direct bearing on free-will decisions made ("thoughtfully") by the subject over the course of many seconds, minutes, hours or longer. Scientists have also only so far studied extremely simple behaviors (e.g. moving a finger). Adina Roskies points out five areas of neuroscientific research: 1) action initiation, 2) intention, 3) decision, 4) inhibition and control, 5) the phenomenology of agency; and for each of these areas Roskies concludes that the science may be developing our understanding of volition or "will", but it yet offers nothing for developing the "free" part of the "free will" discussion.

There is also the question of the influence of such interpretations in people's behaviour. In 2008, psychologists Kathleen Vohs and Jonathan Schooler published a study on how people behave when they are prompted to think that determinism is true. They asked their subjects to read one of two passages: one suggesting that behaviour boils down to environmental or genetic factors not under personal control; the other neutral about what influences behaviour. The participants then did a few math problems on a computer. But just before the test started, they were informed that because of a glitch in the computer it occasionally displayed the answer by accident; if this happened, they were to click it away without looking. Those who had read the deterministic message were more likely to cheat on the test. "Perhaps, denying free will simply provides the ultimate excuse to behave as one likes", Vohs and Schooler suggested. However, although initial studies suggested that believing in free will is associated with more morally praiseworthy behavior, some recent studies have reported contradictory findings.

Notable experiments

Libet experiment

A pioneering experiment in this field was conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s, in which he asked each subject to choose a random moment to flick their wrist while he measured the associated activity in their brain (in particular, the build-up of electrical signal called the Bereitschaftspotential (BP), which was discovered by Kornhuber & Deecke in 1965). Although it was well known that the "readiness potential" (German: Bereitschaftspotential) preceded the physical action, Libet asked how it corresponded to the felt intention to move. To determine when the subjects felt the intention to move, he asked them to watch the second hand of a clock and report its position when they felt that they had felt the conscious will to move.

Libet found that the unconscious brain activity leading up to the conscious decision by the subject to flick their wrist began approximately half a second before the subject consciously felt that they had decided to move. Libet's findings suggest that decisions made by a subject are first being made on a subconscious level and only afterward being translated into a "conscious decision", and that the subject's belief that it occurred at the behest of their will was only due to their retrospective perspective on the event.

The interpretation of these findings has been criticized by Daniel Dennett, who argues that people will have to shift their attention from their intention to the clock, and that this introduces temporal mismatches between the felt experience of will and the perceived position of the clock hand. Consistent with this argument, subsequent studies have shown that the exact numerical value varies depending on attention. Despite the differences in the exact numerical value, however, the main finding has held. Philosopher Alfred Mele criticizes this design for other reasons. Having attempted the experiment himself, Mele explains that "the awareness of the intention to move" is an ambiguous feeling at best. For this reason he remained skeptical of interpreting the subjects' reported times for comparison with their "Bereitschaftspotential".

Criticisms

In a variation of this task, Haggard and Eimer asked subjects to decide not only when to move their hands, but also to decide which hand to move. In this case, the felt intention correlated much more closely with the "lateralized readiness potential" (LRP), an event-related potential (ERP) component that measures the difference between left and right hemisphere brain activity. Haggard and Eimer argue that the feeling of conscious will must therefore follow the decision of which hand to move, since the LRP reflects the decision to lift a particular hand.

A more direct test of the relationship between the Bereitschaftspotential and the "awareness of the intention to move" was conducted by Banks and Isham (2009). In their study, participants performed a variant of the Libet's paradigm in which a delayed tone followed the button press. Subsequently, research participants reported the time of their intention to act (e.g., Libet's "W"). If W were time-locked to the Bereitschaftspotential, W would remain uninfluenced by any post-action information. However, findings from this study show that W in fact shifts systematically with the time of the tone presentation, implicating that W is, at least in part, retrospectively reconstructed rather than pre-determined by the Bereitschaftspotential.

A study conducted by Jeff Miller and Judy Trevena (2009) suggests that the Bereitschaftspotential (BP) signal in Libet's experiments doesn't represent a decision to move, but that it's merely a sign that the brain is paying attention. In this experiment the classical Libet experiment was modified by playing an audio tone indicating to volunteers to decide whether to tap a key or not. The researchers found that there was the same RP signal in both cases, regardless of whether or not volunteers actually elected to tap, which suggests that the RP signal doesn't indicate that a decision has been made.

In a second experiment, researchers asked volunteers to decide on the spot whether to use left hand or right to tap the key while monitoring their brain signals, and they found no correlation among the signals and the chosen hand. This criticism has itself been criticized by free-will researcher Patrick Haggard, who mentions literature that distinguishes two different circuits in the brain that lead to action: a "stimulus-response" circuit and a "voluntary" circuit. According to Haggard, researchers applying external stimuli may not be testing the proposed voluntary circuit, nor Libet's hypothesis about internally triggered actions.

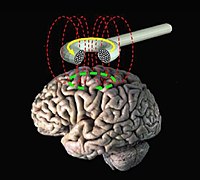

Libet's interpretation of the ramping up of brain activity prior to the report of conscious "will" continues to draw heavy criticism. Studies have questioned participants' ability to report the timing of their "will". Authors have found that preSMA activity is modulated by attention (attention precedes the movement signal by 100 ms), and the prior activity reported could therefore have been product of paying attention to the movement. They also found that the perceived onset of intention depends on neural activity that takes place after the execution of action. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) applied over the preSMA after a participant performed an action shifted the perceived onset of the motor intention backward in time, and the perceived time of action execution forward in time.

Others have speculated that the preceding neural activity reported by Libet may be an artefact of averaging the time of "will", wherein neural activity does not always precede reported "will". In a similar replication they also reported no difference in electrophysiological signs before a decision not to move and before a decision to move.

Despite the popular interpretation of his findings, Libet himself did not interpret his experiment as evidence of the inefficacy of conscious free will — he points out that although the tendency to press a button may be building up for 500 milliseconds, the conscious will retains a right to veto any action at the last moment. According to this model, unconscious impulses to perform a volitional act are open to suppression by the conscious efforts of the subject (sometimes referred to as "free won't"). A comparison is made with a golfer, who may swing a club several times before striking the ball. The action simply gets a rubber stamp of approval at the last millisecond. Max Velmans argues however that "free won't" may turn out to need as much neural preparation as "free will" (see below).

Some studies have, however, replicated Libet's findings, whilst addressing some of the original criticisms. A 2011 study conducted by Itzhak Fried found that individual neurons fire 2 seconds before a reported "will" to act (long before EEG activity predicted such a response). This was accomplished with the help of volunteer epilepsy patients, who needed electrodes implanted deep in their brain for evaluation and treatment anyway. Now able to monitor awake and moving patients, the researchers replicated the timing anomalies that were discovered by Libet. Similarly to these tests, Chun Siong Soon, Anna Hanxi He, Stefan Bode and John-Dylan Haynes have conducted a study in 2013 claiming to be able to predict the choice to sum or subtract before the subject reports it.

William R. Klemm pointed out the inconclusiveness of these tests due to design limitations and data interpretations and proposed less ambiguous experiments, while affirming a stand on the existence of free will like Roy F. Baumeister or Catholic neuroscientists such as Tadeusz Pacholczyk. Adrian G. Guggisberg and Annaïs Mottaz have also challenged Itzhak Fried's findings.

A study by Aaron Schurger and colleagues published in PNAS challenged assumptions about the causal nature of the Bereitschaftspotential itself (and the "pre-movement buildup" of neural activity in general when faced with a choice), thus denying the conclusions drawn from studies such as Libet's and Fried's. See The Information Philosopher, New Scientist, and the Atlantic for commentary on this study.

Unconscious actions

Timing intentions compared to actions

A study by Masao Matsuhashi and Mark Hallett, published in 2008, claims to have replicated Libet's findings without relying on subjective report or clock memorization on the part of participants. The authors believe that their method can identify the time (T) at which a subject becomes aware of his own movement. Matsuhashi and Hallet argue that T not only varies, but often occurs after early phases of movement genesis have already begun (as measured by the readiness potential). They conclude that a person's awareness cannot be the cause of movement, and may instead only notice the movement.

The experiment

Matsuhashi and Hallett's study can be summarized thus. The researchers hypothesized that, if our conscious intentions are what causes movement genesis (i.e. the start of an action), then naturally, our conscious intentions should always occur before any movement has begun. Otherwise, if we ever become aware of a movement only after it has already been started, our awareness could not have been the cause of that particular movement. Simply put, conscious intention must precede action if it is its cause.

To test this hypothesis, Matsuhashi and Hallet had volunteers perform brisk finger movements at random intervals, while not counting or planning when to make such (future) movements, but rather immediately making a movement as soon as they thought about it. An externally controlled "stop-signal" sound was played at pseudo-random intervals, and the volunteers had to cancel their intent to move if they heard a signal while being aware of their own immediate intention to move. Whenever there was an action (finger movement), the authors documented (and graphed) any tones that occurred before that action. The graph of tones before actions therefore only shows tones (a) before the subject is even aware of his "movement genesis" (or else they would have stopped or "vetoed" the movement), and (b) after it is too late to veto the action. This second set of graphed tones is of little importance here.

In this work, "movement genesis" is defined as the brain process of making movement, of which physiological observations have been made (via electrodes) indicating that it may occur before conscious awareness of intent to move.

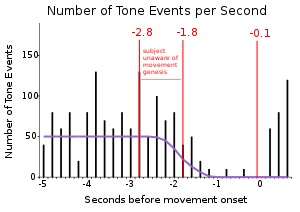

By looking to see when tones started preventing actions, the researchers supposedly know the length of time (in seconds) that exists between when a subject holds a conscious intention to move and performs the action of movement. This moment of awareness is called "T" (the mean time of conscious intention to move). It can be found by looking at the border between tones and no tones. This enables the researchers to estimate the timing of the conscious intention to move without relying on the subject's knowledge or demanding them to focus on a clock. The last step of the experiment is to compare time T for each subject with their event-related potential (ERP) measures (e.g. seen in this page's lead image), which reveal when their finger movement genesis first begins.

The researchers found that the time of the conscious intention to move T normally occurred too late to be the cause of movement genesis. See the example of a subject's graph below on the right. Although it is not shown on the graph, the subject's readiness potentials (ERP) tells us that his actions start at −2.8 seconds, and yet this is substantially earlier than his conscious intention to move, time "T" (−1.8 seconds). Matsuhashi and Hallet concluded that the feeling of the conscious intention to move does not cause movement genesis; both the feeling of intention and the movement itself are the result of unconscious processing.

Analysis and interpretation

This study is similar to Libet's in some ways: volunteers were again asked to perform finger extensions in short, self-paced intervals. In this version of the experiment, researchers introduced randomly timed "stop tones" during the self-paced movements. If participants were not conscious of any intention to move, they simply ignored the tone. On the other hand, if they were aware of their intention to move at the time of the tone, they had to try to veto the action, then relax for a bit before continuing self-paced movements. This experimental design allowed Matsuhashi and Hallet to see when, once the subject moved his finger, any tones occurred. The goal was to identify their own equivalent of Libet's W, their own estimation of the timing of the conscious intention to move, which they would call "T" (time).

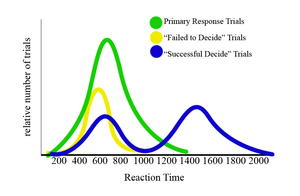

Testing the hypothesis that "conscious intention occurs after movement genesis has already begun" required the researchers to analyse the distribution of responses to tones before actions. The idea is that, after time T, tones will lead to vetoing and thus a reduced representation in the data. There would also be a point of no return P where a tone was too close to the movement onset for the movement to be vetoed. In other words, the researchers were expecting to see the following on the graph: many unsuppressed responses to tones while the subjects are not yet aware of their movement genesis, followed by a drop in the number of unsuppressed responses to tones during a certain period of time during which the subjects are conscious of their intentions and are stopping any movements, and finally a brief increase again in unsuppressed responses to tones when the subjects do not have the time to process the tone and prevent an action – they have passed the action's "point of no return". That is exactly what the researchers found (see the graph on the right, below).

The graph shows the times at which unsuppressed responses to tones occurred when the volunteer moved. He showed many unsuppressed responses to tones (called "tone events" on the graph) on average up until 1.8 seconds before movement onset, but a significant decrease in tone events immediately after that time. Presumably this is because the subject usually became aware of his intention to move at about −1.8 seconds, which is then labelled point T. Since most actions are vetoed if a tone occurs after point T, there are very few tone events represented during that range. Finally, there is a sudden increase in the number of tone events at 0.1 seconds, meaning that this subject has passed point P. Matsuhashi and Hallet were thus able to establish an average time T (−1.8 seconds) without subjective report. This, they compared to ERP measurements of movement, which had detected movement beginning at about −2.8 seconds on average for this participant. Since T, like Libet's original W, was often found after movement genesis had already begun, the authors concluded that the generation of awareness occurred afterwards or in parallel to action, but most importantly, that it was probably not the cause of the movement.

Criticisms

Haggard describes other studies at the neuronal levels as providing "a reassuring confirmation of previous studies that recorded neural populations" such as the one just described. Note that these results were gathered using finger movements and may not necessarily generalize to other actions such as thinking, or even other motor actions in different situations. Indeed, the human act of planning has implications for free will, and so this ability must also be explained by any theories of unconscious decision making. Philosopher Alfred Mele also doubts the conclusions of these studies. He explains that simply because a movement may have been initiated before our "conscious self" has become aware of it does not mean that our consciousness does not still get to approve, modify, and perhaps cancel (called vetoing) the action.

Unconsciously cancelling actions

The possibility that human "free won't" is also the prerogative of the subconscious is being explored.

Retrospective judgement of free choice

Recent research by Simone Kühn and Marcel Brass suggests that our consciousness may not be what causes some actions to be vetoed at the last moment. First of all, their experiment relies on the simple idea that we ought to know when we consciously cancel an action (i.e. we should have access to that information). Secondly, they suggest that access to this information means humans should find it easy to tell, just after completing an action, whether it was impulsive (there being no time to decide) and when there was time to deliberate (the participant decided to allow/not to veto the action). The study found evidence that subjects could not tell this important difference. This again leaves some conceptions of free will vulnerable to the introspection illusion. The researchers interpret their results to mean that the decision to "veto" an action is determined subconsciously, just as the initiation of the action may have been subconscious in the first place.

The experiment

The experiment involved asking volunteers to respond to a go-signal by pressing an electronic "go" button as quickly as possible. In this experiment the go-signal was represented as a visual stimulus shown on a monitor (e.g. a green light as shown on the picture). The participants' reaction times (RT) were gathered at this stage, in what was described as the "primary response trials".

The primary response trials were then modified, in which 25% of the go-signals were subsequently followed by an additional signal – either a "stop" or "decide" signal. The additional signals occurred after a "signal delay" (SD), a random amount of time up to 2 seconds after the initial go-signal. They also occurred equally, each representing 12.5% of experimental cases. These additional signals were represented by the initial stimulus changing colour (e.g. to either a red or orange light). The other 75% of go-signals were not followed by an additional signal, and therefore considered the "default" mode of the experiment. The participants' task of responding as quickly as possible to the initial signal (i.e. pressing the "go" button) remained.

Upon seeing the initial go-signal, the participant would immediately intend to press the "go" button. The participant was instructed to cancel their immediate intention to press the "go" button if they saw a stop signal. The participant was instructed to select randomly (at their leisure) between either pressing the "go" button or not pressing it, if they saw a decide signal. Those trials in which the decide signal was shown after the initial go-signal ("decide trials"), for example, required that the participants prevent themselves from acting impulsively on the initial go-signal and then decide what to do. Due to the varying delays, this was sometimes impossible (e.g. some decide signals simply appeared too late in the process of them both intending to and pressing the go button for them to be obeyed).

Those trials in which the subject reacted to the go-signal impulsively without seeing a subsequent signal show a quick RT of about 600 ms. Those trials in which the decide signal was shown too late, and the participant had already enacted their impulse to press the go-button (i.e. had not decided to do so), also show a quick RT of about 600 ms. Those trials in which a stop signal was shown and the participant successfully responded to it, do not show a response time. Those trials in which a decide signal was shown, and the participant decided not to press the go-button, also do not show a response time. Those trials in which a decide signal was shown, and the participant had not already enacted their impulse to press the go-button, but (in which it was theorised that they) had had the opportunity to decide what to do, show a comparatively slow RT, in this case closer to 1400 ms.

The participant was asked at the end of those "decide trials" in which they had actually pressed the go-button whether they had acted impulsively (without enough time to register the decide signal before enacting their intent to press the go-button in response to the initial go-signal stimulus) or based upon a conscious decision made after seeing the decide signal. Based upon the response time data, however, it appears that there was discrepancy between when the user thought that they had had the opportunity to decide (and had therefore not acted on their impulses) – in this case deciding to press the go-button, and when they thought that they had acted impulsively (based upon the initial go-signal) – where the decide signal came too late to be obeyed.

The rationale

Kuhn and Brass wanted to test participant self-knowledge. The first step was that after every decide trial, participants were next asked whether they had actually had time to decide. Specifically, the volunteers were asked to label each decide trial as either failed-to-decide (the action was the result of acting impulsively on the initial go-signal) or successful decide (the result of a deliberated decision). See the diagram on the right for this decide trial split: failed-to-decide and successful decide; the next split in this diagram (participant correct or incorrect) will be explained at the end of this experiment. Note also that the researchers sorted the participants’ successful decide trials into "decide go" and "decide no-go", but were not concerned with the no-go trials, since they did not yield any RT data (and are not featured anywhere in the diagram on the right). Note that successful stop trials did not yield RT data either.

Kuhn and Brass now knew what to expect: primary response trials, any failed stop trials, and the "failed-to-decide" trials were all instances where the participant obviously acted impulsively – they would show the same quick RT. In contrast, the "successful decide" trials (where the decision was a "go" and the subject moved) should show a slower RT. Presumably, if deciding whether to veto is a conscious process, volunteers should have no trouble distinguishing impulsivity from instances of true deliberate continuation of a movement. Again, this is important, since decide trials require that participants rely on self-knowledge. Note that stop trials cannot test self-knowledge because if the subject does act, it is obvious to them that they reacted impulsively.

Results and implications

Unsurprisingly, the recorded RTs for the primary response trials, failed stop trials, and "failed-to-decide" trials all showed similar RTs: 600 ms seems to indicate an impulsive action made without time to truly deliberate. What the two researchers found next was not as easy to explain: while some "successful decide" trials did show the tell-tale slow RT of deliberation (averaging around 1400 ms), participants had also labelled many impulsive actions as "successful decide". This result is startling because participants should have had no trouble identifying which actions were the results of a conscious "I will not veto", and which actions were un-deliberated, impulsive reactions to the initial go-signal. As the authors explain:

[The results of the experiment] clearly argue against Libet's assumption that a veto process can be consciously initiated. He used the veto in order to reintroduce the possibility to control the unconsciously initiated actions. But since the subjects are not very accurate in observing when they have [acted impulsively instead of deliberately], the act of vetoing cannot be consciously initiated.

In decide trials the participants, it seems, were not able to reliably identify whether they had really had time to decide – at least, not based on internal signals. The authors explain that this result is difficult to reconcile with the idea of a conscious veto, but is simple to understand if the veto is considered an unconscious process. Thus it seems that the intention to move might not only arise from the subconscious, but it may only be inhibited if the subconscious says so. This conclusion could suggest that the phenomenon of "consciousness" is more of narration than direct arbitration (i.e. unconscious processing causes all thoughts, and these thoughts are again processed subconsciously).

Criticisms

After the above experiments, the authors concluded that subjects sometimes could not distinguish between "producing an action without stopping and stopping an action before voluntarily resuming", or in other words, they could not distinguish between actions that are immediate and impulsive as opposed to delayed by deliberation. To be clear, one assumption of the authors is that all the early (600 ms) actions are unconscious, and all the later actions are conscious. These conclusions and assumptions have yet to be debated within the scientific literature or even replicated (it is a very early study).

The results of the trial in which the so-called "successful decide" data (with its respective longer time measured) was observed may have possible implications for our understanding of the role of consciousness as the modulator of a given action or response, and these possible implications cannot merely be omitted or ignored without valid reasons, specially when the authors of the experiment suggest that the late decide trials were actually deliberated.

It is worth noting that Libet consistently referred to a veto of an action that was initiated endogenously. That is, a veto that occurs in the absence of external cues, instead relying on only internal cues (if any at all). This veto may be a different type of veto than the one explored by Kühn and Brass using their decide signal.

Daniel Dennett also argues that no clear conclusion about volition can be derived from Benjamin Libet's experiments supposedly demonstrating the non-existence of conscious volition. According to Dennett, ambiguities in the timings of the different events are involved. Libet tells when the readiness potential occurs objectively, using electrodes, but relies on the subject reporting the position of the hand of a clock to determine when the conscious decision was made. As Dennett points out, this is only a report of where it seems to the subject that various things come together, not of the objective time at which they actually occur:

Suppose Libet knows that your readiness potential peaked at millisecond 6,810 of the experimental trial, and the clock dot was straight down (which is what you reported you saw) at millisecond 7,005. How many milliseconds should he have to add to this number to get the time you were conscious of it? The light gets from your clock face to your eyeball almost instantaneously, but the path of the signals from retina through lateral geniculate nucleus to striate cortex takes 5 to 10 milliseconds — a paltry fraction of the 300 milliseconds offset, but how much longer does it take them to get to you. (Or are you located in the striate cortex?) The visual signals have to be processed before they arrive at wherever they need to arrive for you to make a conscious decision of simultaneity. Libet's method presupposes, in short, that we can locate the intersection of two trajectories:

- the rising-to-consciousness of signals representing the decision to flick

- the rising to consciousness of signals representing successive clock-face orientations

so that these events occur side-by-side as it were in place where their simultaneity can be noted.

The point of no return

In early 2016, PNAS published an article by researchers in Berlin, Germany, The point of no return in vetoing self-initiated movements, in which the authors set out to investigate whether human subjects had the ability to veto an action (in this study, a movement of the foot) after the detection of its Bereitschaftspotential (BP). The Bereitschaftspotential, which was discovered by Kornhuber & Deecke in 1965, is an instance of unconscious electrical activity within the motor cortex, quantified by the use of EEG, that occurs moments before a motion is performed by a person: it is considered a signal that the brain is "getting ready" to perform the motion. The study found evidence that these actions can be vetoed even after the BP is detected (i. e. after it can be seen that the brain has started preparing for the action). The researchers maintain that this is evidence for the existence of at least some degree of free will in humans: previously, it had been argued that, given the unconscious nature of the BP and its usefulness in predicting a person's movement, these are movements that are initiated by the brain without the involvement of the conscious will of the person. The study showed that subjects were able to "override" these signals and stop short of performing the movement that was being anticipated by the BP. Furthermore, researchers identified what was termed a "point of no return": once the BP is detected for a movement, the person could refrain from performing the movement only if they attempted to cancel it at least 200 milliseconds before the onset of the movement. After this point, the person was unable to avoid performing the movement. Previously, Kornhuber and Deecke underlined that absence of conscious will during the early Bereitschaftspotential (termed BP1) is not a proof of the non-existence of free will, as also unconscious agendas may be free and non-deterministic. According to their suggestion, man has relative freedom, i.e. freedom in degrees, that can be increased or decreased through deliberate choices that involve both conscious and unconscious (panencephalic) processes.

Neuronal prediction of free will

Despite criticisms, experimenters are still trying to gather data that may support the case that conscious "will" can be predicted from brain activity. fMRI machine learning of brain activity (multivariate pattern analysis) has been used to predict the user choice of a button (left/right) up to 7 seconds before their reported will of having done so. Brain regions successfully trained for prediction included the frontopolar cortex (anterior medial prefrontal cortex) and precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex (medial parietal cortex). In order to ensure report timing of conscious "will" to act, they showed the participant a series of frames with single letters (500 ms apart), and upon pressing the chosen button (left or right) they were required to indicate which letter they had seen at the moment of decision. This study reported a statistically significant 60% accuracy rate, which may be limited by experimental setup; machine-learning data limitations (time spent in fMRI) and instrument precision.

Another version of the fMRI multivariate pattern analysis experiment was conducted using an abstract decision problem, in an attempt to rule out the possibility of the prediction capabilities being product of capturing a built-up motor urge. Each frame contained a central letter like before, but also a central number, and 4 surrounding possible "answers numbers". The participant first chose in their mind whether they wished to perform an addition or subtraction operation, and noted the central letter on the screen at the time of this decision. The participant then performed the mathematical operation based on the central numbers shown in the next two frames. In the following frame the participant then chose the "answer number" corresponding to the result of the operation. They were further presented with a frame that allowed them to indicate the central letter appearing on the screen at the time of their original decision. This version of the experiment discovered a brain prediction capacity of up to 5 seconds before the conscious will to act.

Multivariate pattern analysis using EEG has suggested that an evidence-based perceptual decision model may be applicable to free-will decisions. It was found that decisions could be predicted by neural activity immediately after stimulus perception. Furthermore, when the participant was unable to determine the nature of the stimulus, the recent decision history predicted the neural activity (decision). The starting point of evidence accumulation was in effect shifted towards a previous choice (suggesting a priming bias). Another study has found that subliminally priming a participant for a particular decision outcome (showing a cue for 13 ms) could be used to influence free decision outcomes. Likewise, it has been found that decision history alone can be used to predict future decisions. The prediction capacities of the Soon et al. (2008) experiment were successfully replicated using a linear SVM model based on participant decision history alone (without any brain activity data). Despite this, a recent study has sought to confirm the applicability of a perceptual decision model to free will decisions. When shown a masked and therefore invisible stimulus, participants were asked to either guess between a category or make a free decision for a particular category. Multivariate pattern analysis using fMRI could be trained on "free-decision" data to successfully predict "guess decisions", and trained on "guess data" in order to predict "free decisions" (in the precuneus and cuneus region).

Contemporary voluntary decision prediction tasks have been criticised based on the possibility the neuronal signatures for pre-conscious decisions could actually correspond to lower-conscious processing rather than unconscious processing. People may be aware of their decisions before making their report, yet need to wait several seconds to be certain. However, such a model does not explain what is left unconscious if everything can be conscious at some level (and the purpose of defining separate systems). Yet limitations remain in free-will prediction research to date. In particular, the prediction of considered judgements from brain activity involving thought processes beginning minutes rather than seconds before a conscious will to act, including the rejection of a conflicting desire. Such are generally seen to be the product of sequences of evidence accumulating judgements.

Retrospective construction

It has been suggested that sense authorship is an illusion. Unconscious causes of thought and action might facilitate thought and action, while the agent experiences the thoughts and actions as being dependent on conscious will. We may over-assign agency because of the evolutionary advantage that once came with always suspecting there might be an agent doing something (e.g. predator). The idea behind retrospective construction is that, while part of the "yes, I did it" feeling of agency seems to occur during action, there also seems to be processing performed after the fact – after the action is performed – to establish the full feeling of agency.

Unconscious agency processing can even alter, in the moment, how we perceive the timing of sensations or actions. Kühn and Brass apply retrospective construction to explain the two peaks in "successful decide" RTs. They suggest that the late decide trials were actually deliberated, but that the impulsive early decide trials that should have been labelled "failed to decide" were mistaken during unconscious agency processing. They say that people "persist in believing that they have access to their own cognitive processes" when in fact we do a great deal of automatic unconscious processing before conscious perception occurs.

Criticism to Wegner's claims regarding the significance of introspection illusion for the notion of free will has been published.

Manipulating choice

Some research suggests that TMS can be used to manipulate the perception of authorship of a specific choice. Experiments showed that neurostimulation could affect which hands people move, even though the experience of free will was intact. An early TMS study revealed that activation of one side of the neocortex could be used to bias the selection of one's opposite side hand in a forced-choice decision task. Ammon and Gandevia found that it was possible to influence which hand people move by stimulating frontal regions that are involved in movement planning using transcranial magnetic stimulation in the left or right hemisphere of the brain.

Right-handed people would normally choose to move their right hand 60% of the time, but when the right hemisphere was stimulated, they would instead choose their left hand 80% of the time (recall that the right hemisphere of the brain is responsible for the left side of the body, and the left hemisphere for the right). Despite the external influence on their decision-making, the subjects continued to report believing that their choice of hand had been made freely. In a follow-up experiment, Alvaro Pascual-Leone and colleagues found similar results, but also noted that the transcranial magnetic stimulation must occur within 200 milliseconds, consistent with the time-course derived from the Libet experiments.

In late 2015, a team of researchers from the UK and the US published an article demonstrating similar findings. The researchers concluded that "motor responses and the choice of hand can be modulated using tDCS". However, a different attempt by Sohn et al. failed to replicate such results; later, Jeffrey Gray wrote in his book Consciousness: Creeping up on the Hard Problem that tests looking for the influence of electromagnetic fields on brain function have been universally negative in their result.

Manipulating the perceived intention to move

Various studies indicate that the perceived intention to move (have moved) can be manipulated. Studies have focused on the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA) of the brain, in which readiness potential indicating the beginning of a movement genesis has been recorded by EEG. In one study, directly stimulating the pre-SMA caused volunteers to report a feeling of intention, and sufficient stimulation of that same area caused physical movement. In a similar study, it was found that people with no visual awareness of their body can have their limbs be made to move without having any awareness of this movement, by stimulating premotor brain regions. When their parietal cortices were stimulated, they reported an urge (intention) to move a specific limb (that they wanted to do so). Furthermore, stronger stimulation of the parietal cortex resulted in the illusion of having moved without having done so.

This suggests that awareness of an intention to move may literally be the "sensation" of the body's early movement, but certainly not the cause. Other studies have at least suggested that "The greater activation of the SMA, SACC, and parietal areas during and after execution of internally generated actions suggests that an important feature of internal decisions is specific neural processing taking place during and after the corresponding action. Therefore, awareness of intention timing seems to be fully established only after execution of the corresponding action, in agreement with the time course of neural activity observed here."

Another experiment involved an electronic ouija board where the device's movements were manipulated by the experimenter, while the participant was led to believe that they were entirely self-conducted. The experimenter stopped the device on occasions and asked the participant how much they themselves felt like they wanted to stop. The participant also listened to words in headphones, and it was found that if experimenter stopped next to an object that came through the headphones, they were more likely to say that they wanted to stop there. If the participant perceived having the thought at the time of the action, then it was assigned as intentional. It was concluded that a strong illusion of perception of causality requires: priority (we assume the thought must precede the action), consistency (the thought is about the action), and exclusivity (no other apparent causes or alternative hypotheses).

Lau et al. set up an experiment where subjects would look at an analog-style clock, and a red dot would move around the screen. Subjects were told to click the mouse button whenever they felt the intention to do so. One group was given a transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) pulse, and the other was given a sham TMS. Subjects in the intention condition were told to move the cursor to where it was when they felt the inclination to press the button. In the movement condition, subjects moved their cursor to where it was when they physically pressed the button. Results showed that the TMS was able to shift the perceived intention forward by 16 ms, and shifted back the 14 ms for the movement condition. Perceived intention could be manipulated up to 200 ms after the execution of the spontaneous action, indicating that the perception of intention occurred after the executive motor movements. Often it is thought that if free will were to exist, it would require intention to be the causal source of behavior. These results show that intention may not be the causal source of all behavior.

Related models

The idea that intention co-occurs with (rather than causes) movement is reminiscent of "forward models of motor control" (FMMC), which have been used to try to explain inner speech. FMMCs describe parallel circuits: movement is processed in parallel with other predictions of movement; if the movement matches the prediction, the feeling of agency occurs. FMMCs have been applied in other related experiments. Metcalfe and her colleagues used an FMMC to explain how volunteers determine whether they are in control of a computer game task. On the other hand, they acknowledge other factors too. The authors attribute feelings of agency to desirability of the results and top-down processing (reasoning and inferences about the situation).

In this case, it is by the application of the forward model that one might imagine how other consciousness processes could be the result of efferent, predictive processing. If the conscious self is the efferent copy of actions and vetoes being performed, then the consciousness is a sort of narrator of what is already occurring in the body, and an incomplete narrator at that. Haggard, summarizing data taken from recent neuron recordings, says "these data give the impression that conscious intention is just a subjective corollary of an action being about to occur". Parallel processing helps explain how we might experience a sort of contra-causal free will even if it were determined.

How the brain constructs consciousness is still a mystery, and cracking it open would have a significant bearing on the question of free will. Numerous different models have been proposed, for example, the multiple drafts model, which argues that there is no central Cartesian theater where conscious experience would be represented, but rather that consciousness is located all across the brain. This model would explain the delay between the decision and conscious realization, as experiencing everything as a continuous "filmstrip" comes behind the actual conscious decision. In contrast, there exist models of Cartesian materialism that have gained recognition by neuroscience, implying that there might be special brain areas that store the contents of consciousness; this does not, however, rule out the possibility of a conscious will. Other models such as epiphenomenalism argue that conscious will is an illusion, and that consciousness is a by-product of physical states of the world. Work in this sector is still highly speculative, and researchers favor no single model of consciousness.

Related brain disorders

Various brain disorders implicate the role of unconscious brain processes in decision-making tasks. Auditory hallucinations produced by schizophrenia seem to suggest a divergence of will and behaviour. The left brain of people whose hemispheres have been disconnected has been observed to invent explanations for body movement initiated by the opposing (right) hemisphere, perhaps based on the assumption that their actions are consciously willed. Likewise, people with "alien hand syndrome" are known to conduct complex motor movements against their will.

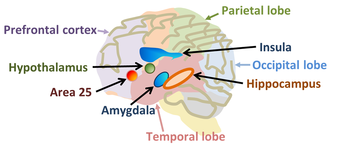

Neural models of voluntary action

A neural model for voluntary action proposed by Haggard comprises two major circuits. The first involving early preparatory signals (basal ganglia substantia nigra and striatum), prior intention and deliberation (medial prefrontal cortex), motor preparation/readiness potential (preSMA and SMA), and motor execution (primary motor cortex, spinal cord and muscles). The second involving the parietal-pre-motor circuit for object-guided actions, for example grasping (premotor cortex, primary motor cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, parietal cortex, and back to the premotor cortex). He proposed that voluntary action involves external environment input ("when decision"), motivations/reasons for actions (early "whether decision"), task and action selection ("what decision"), a final predictive check (late "whether decision") and action execution.

Another neural model for voluntary action also involves what, when, and whether (WWW) based decisions. The "what" component of decisions is considered a function of the anterior cingulate cortex, which is involved in conflict monitoring. The timing ("when") of the decisions are considered a function of the preSMA and SMA, which is involved in motor preparation. Finally, the "whether" component is considered a function of the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex.

Prospection

Martin Seligman and others criticize the classical approach in science that views animals and humans as "driven by the past" and suggest instead that people and animals draw on experience to evaluate prospects they face and act accordingly. The claim is made that this purposive action includes evaluation of possibilities that have never occurred before and is experimentally verifiable.

Seligman and others argue that free will and the role of subjectivity in consciousness can be better understood by taking such a "prospective" stance on cognition and that "accumulating evidence in a wide range of research suggests [this] shift in framework".