The bourgeoisie are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted with the proletariat by their wealth, political power, and education, as well as their access to and control of cultural, social, and financial capital.

The bourgeoisie in its original sense is intimately linked to the political ideology of liberalism and its existence within cities, recognised as such by their urban charters (e.g., municipal charters, town privileges, German town law), so there was no bourgeoisie apart from the citizenry of the cities. Rural peasants came under a different legal system.

In communist philosophy, the bourgeoisie is the social class that came to own the means of production during modern industrialisation and whose societal concerns are the value of private property and the preservation of capital to ensure the perpetuation of their economic dominance in society.

Etymology

The Modern French word bourgeois is derived from the Old French borgeis or borjois ('town dweller'), which derived from bourg ('market town'), from the Old Frankish burg ('town'); in other European languages, the etymologic derivations include the Middle English burgeis, the Middle Dutch burgher, the German Bürger, the Modern English burgess, the Spanish burgués, the Portuguese burguês, and the Polish burżuazja, which occasionally is synonymous with the intelligentsia.

In the 18th century, before the French Revolution (1789–1799), in the French Ancien Régime, the masculine and feminine terms bourgeois and bourgeoise identified the relatively rich men and women who were members of the urban and rural Third Estate – the common people of the French realm, who violently deposed the absolute monarchy of the Bourbon King Louis XVI (r. 1774–1791), his clergy, and his aristocrats in the French Revolution of 1789–1799. Hence, since the 19th century, the term bourgeoisie usually is politically and sociologically synonymous with the ruling upper class of a capitalist society. In English, the word bourgeoisie, as a term referring to French history, refers to a social class oriented to economic materialism and hedonism, and to upholding the political and economic interests of the capitalist ruling-class.

Historically, the medieval French word bourgeois denoted the inhabitants of the bourgs (walled market-towns), the craftsmen, artisans, merchants, and others, who constituted "the bourgeoisie". They were the socio-economic class between the peasants and the landlords, between the workers and the owners of the means of production, the feudal nobility. As the economic managers of the (raw) materials, the goods, and the services, and thus the capital (money) produced by the feudal economy, the term bourgeoisie evolved to also denote the middle class – the businessmen who accumulated, administered, and controlled the capital that made possible the development of the bourgs into cities.

Contemporarily, the terms bourgeoisie and bourgeois (noun) identify the ruling class in capitalist societies, as a social stratum, while bourgeois (adjective or noun modifier) describes the Weltanschauung (worldview) of men and women whose way of thinking is socially and culturally determined by their economic materialism and philistinism, a social identity famously mocked in Molière's comedy Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (1670), which satirizes buying the trappings of a noble-birth identity as the means of climbing the social ladder. The 18th century saw a partial rehabilitation of bourgeois values in genres such as the drame bourgeois (bourgeois drama) and "bourgeois tragedy".

Emerging in the 1970s, the shortened term bougie became slang, referring to things or attitudes which are middle class, pretentious and suburban. In 2016, hip-hop group Migos produced a song "Bad and Boujee", featuring an intentional misspelling of the word as boujee – a term which has particularly been used by African Americans in reference to African Americans. The term refers to a person of lower or middle class doing pretentious activities or virtue signalling as an affectation of the upper-class.

History

Origins and rise

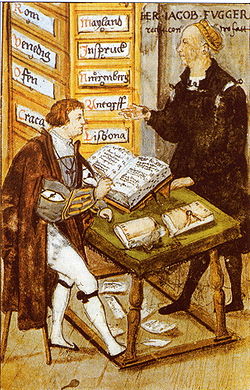

The bourgeoisie emerged as a historical and political phenomenon in the 11th century when the bourgs of Central and Western Europe developed into cities dedicated to commerce and crafts. This urban expansion was possible thanks to economic concentration due to the appearance of protective self-organization into guilds. Guilds arose when individual businessmen (such as craftsmen, artisans and merchants) conflicted with their rent-seeking feudal landlords who demanded greater rents than previously agreed.

In the event, by the end of the Middle Ages (c. AD 1500), under regimes of the early national monarchies of Western Europe, the bourgeoisie acted in self-interest, and politically supported the king or queen against legal and financial disorder caused by the greed of the feudal lords. In the late-16th and early 17th centuries, the bourgeoisies of England and the Netherlands had become the financial – thus political – forces that deposed the feudal order; economic power had vanquished military power in the realm of politics.

From progress to reaction (Marxist view)

According to the Marxist view of history, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the bourgeoisie were the politically progressive social class who supported the principles of constitutional government and of natural right, against the Law of Privilege and the claims of rule by divine right that the nobles and prelates had autonomously exercised during the feudal order.

The English Civil War (1642–1651), the American War of Independence (1775–1783), and French Revolution (1789–1799) were partly motivated by the desire of the bourgeoisie to rid themselves of the feudal and royal encroachments on their personal liberty, commercial prospects, and the ownership of property. In the 19th century, the bourgeoisie propounded liberalism, and gained political rights, religious rights, and civil liberties for themselves and the lower social classes; thus the bourgeoisie was a progressive philosophic and political force in Western societies.

After the Industrial Revolution (1750–1850), by the mid-19th century the great expansion of the bourgeoisie social class caused its stratification – by business activity and by economic function – into the haute bourgeoisie (bankers and industrialists) and the petite bourgeoisie (tradesmen and white-collar workers). Moreover, by the end of the 19th century, the capitalists (the original bourgeoisie) had ascended to the upper class, while the developments of technology and technical occupations allowed the rise of working-class men and women to the lower strata of the bourgeoisie; yet the social progress was incidental.

Denotations

Marxist theory

According to Karl Marx, the bourgeois during the Middle Ages usually was a self-employed businessman – such as a merchant, banker, or entrepreneur – whose economic role in society was being the financial intermediary to the feudal landlord and the peasant who worked the fief, the land of the lord. Yet, by the 18th century, the time of the Industrial Revolution (1750–1850) and of industrial capitalism, the bourgeoisie had become the economic ruling class who owned the means of production (capital and land), and who controlled the means of coercion (armed forces and legal system, police forces and prison system).

In such a society, the bourgeoisie's ownership of the means of production allowed them to employ and exploit the wage-earning working class (urban and rural), people whose only economic means is labor; and the bourgeois control of the means of coercion suppressed the sociopolitical challenges by the lower classes, and so preserved the economic status quo; workers remained workers, and employers remained employers.

In the 19th century, Marx distinguished two types of bourgeois capitalist:

- the functional capitalists, who are business administrators of the means of production;

- rentier capitalists whose livelihoods derive either from the rent of property or from the interest-income produced by finance capital, or from both.

In the course of economic relations, the working class and the bourgeoisie continually engage in class struggle, where the capitalists exploit the workers, while the workers resist their economic exploitation, which occurs because the worker owns no means of production, and, to earn a living, seeks employment from the bourgeois capitalist; the worker produces goods and services that are property of the employer, who sells them for a price.

Besides describing the social class who owns the means of production, the Marxist use of the term "bourgeois" also describes the consumerist style of life derived from the ownership of capital and real property. Marx acknowledged the bourgeois industriousness that created wealth, but criticised the moral hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie when they ignored the alleged origins of their wealth: the exploitation of the proletariat, the urban and rural workers. Further sense denotations of "bourgeois" describe ideological concepts such as "bourgeois freedom", which is thought to be opposed to substantive forms of freedom; "bourgeois independence"; "bourgeois personal individuality"; the "bourgeois family"; et cetera, all derived from owning capital and property (see The Communist Manifesto, 1848).

France and Francophone countries

In English, the term bourgeoisie is often used to denote the middle classes. In fact, the French term encompasses both the upper and middle economic classes, a misunderstanding which has occurred in other languages as well. The bourgeoisie in France and many French-speaking countries consists of five evolving social layers: petite bourgeoisie, moyenne bourgeoisie, grande bourgeoisie, haute bourgeoisie and ancienne bourgeoisie.

Petite bourgeoisie

The petite bourgeoisie is the equivalent of the modern-day middle class, or refers to "a social class between the middle class and the lower class: the lower middle class".

Nazism

Nazism rejected the Marxist concept of proletarian internationalism and class struggle, and supported the "class struggle between nations", and sought to resolve internal class struggle in the nation while it identified Germany as a proletariat nation fighting against plutocratic nations. The Nazi Party had many working-class supporters and members, and a strong appeal to the middle class. The financial collapse of the white collar middle-class of the 1920s figures much in their strong support of Nazism. In the poor country that was the Weimar Republic of the early 1930s, the Nazi Party realised their social policies with food and shelter for the unemployed and the homeless—who were later recruited into the Brownshirt Sturmabteilung (SA – Storm Detachments).

Adolf Hitler was impressed by the populist antisemitism and the anti-liberal bourgeois agitation of Karl Lueger, who as the mayor of Vienna during Hitler's time in the city, used a rabble-rousing style of oratory that appealed to the wider masses. When asked whether he supported the "bourgeois right-wing", Hitler claimed that Nazism was not exclusively for any class, and he also indicated that it favored neither the left nor the right, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps", stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism."

Hitler distrusted capitalism for being unreliable due to its egotism, and he preferred a state-directed economy that is subordinated to the interests of the Volk. Hitler told a party leader in 1934, "The economic system of our day is the creation of the Jews." Hitler said to Benito Mussolini that capitalism had "run its course". Hitler also said that the business bourgeoisie "know nothing except their profit. 'Fatherland' is only a word for them." Hitler was personally disgusted with the ruling bourgeois elites of Germany during the period of the Weimar Republic, whom he referred to as "cowardly shits".

Fascist Italy

Because of their ascribed cultural excellence as a social class, the Italian fascist régime (1922–45) of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini regarded the bourgeoisie as an obstacle to modernism. Nonetheless, the Fascist state ideologically exploited the Italian bourgeoisie and their materialistic, middle-class spirit, for the more efficient cultural manipulation of the upper (aristocratic) and the lower (working) classes of Italy.

In 1938, Prime Minister Mussolini gave a speech wherein he established a clear ideological distinction between capitalism (the social function of the bourgeoisie) and the bourgeoisie (as a social class), whom he dehumanized by reducing them into high-level abstractions: a moral category and a state of mind. Culturally and philosophically, Mussolini isolated the bourgeoisie from Italian society by portraying them as social parasites upon the fascist Italian state and "The People"; as a social class who drained the human potential of Italian society, in general, and of the working class, in particular; as exploiters who victimized the Italian nation with an approach to life characterized by hedonism and materialism. Nevertheless, despite the slogan The Fascist Man Disdains the "Comfortable" Life, which epitomized the anti-bourgeois principle, in its final years of power, for mutual benefit and profit, the Mussolini fascist régime transcended ideology to merge the political and financial interests of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini with the political and financial interests of the bourgeoisie, the Catholic social circles who constituted the ruling class of Italy.

Philosophically, as a materialist creature, the bourgeois man was stereotyped as irreligious; thus, to establish an existential distinction between the supernatural faith of the Roman Catholic Church and the materialist faith of temporal religion; in The Autarchy of Culture: Intellectuals and Fascism in the 1930s, the priest Giuseppe Marino said that:

Christianity is essentially anti-bourgeois. ... A Christian, a true Christian, and thus a Catholic, is the opposite of a bourgeois.

Culturally, the bourgeois man may be considered effeminate, infantile, or acting in a pretentious manner; describing his philistinism in Bonifica antiborghese (1939), Roberto Paravese comments on the:

Middle class, middle man, incapable of great virtue or great vice: and there would be nothing wrong with that, if only he would be willing to remain as such; but, when his child-like or feminine tendency to camouflage pushes him to dream of grandeur, honours, and thus riches, which he cannot achieve honestly with his own "second-rate" powers, then the average man compensates with cunning, schemes, and mischief; he kicks out ethics, and becomes a bourgeois. The bourgeois is the average man who does not accept to remain such, and who, lacking the strength sufficient for the conquest of essential values—those of the spirit—opts for material ones, for appearances.

The economic security, financial freedom, and social mobility of the bourgeoisie threatened the philosophic integrity of Italian fascism, the ideological monolith that was the régime of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Any assumption of legitimate political power (government and rule) by the bourgeoisie represented a fascist loss of totalitarian state power for social control through political unity—one people, one nation, and one leader. Sociologically, to the fascist man, to become a bourgeois was a character flaw inherent to the masculine mystique; therefore, the ideology of Italian fascism scornfully defined the bourgeois man as "spiritually castrated".

Bourgeois culture

Cultural hegemony

Karl Marx said that the culture of a society is dominated by the mores of the ruling-class, wherein their superimposed value system is abided by each social class (the upper, the middle, the lower) regardless of the socio-economic results it yields to them. In that sense, contemporary societies are bourgeois to the degree that they practice the mores of the small-business "shop culture" of early modern France; which the writer Émile Zola (1840–1902) naturalistically presented, analyzed, and ridiculed in the twenty-two-novel series (1871–1893) about Les Rougon-Macquart family; the thematic thrust is the necessity for social progress, by subordinating the economic sphere to the social sphere of life.

Conspicuous consumption

The critical analyses of the bourgeois mentality by the German intellectual Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) indicated that the shop culture of the petite bourgeoisie established the sitting room as the center of personal and family life; as such, the English bourgeois culture is, he alleges, a sitting-room culture of prestige through conspicuous consumption. The material culture of the bourgeoisie concentrated on mass-produced luxury goods of high quality; between generations, the only variance was the materials with which the goods were manufactured.

In the early part of the 19th century, the bourgeois house contained a home that first was stocked and decorated with hand-painted porcelain, machine-printed cotton fabrics, machine-printed wallpaper, and Sheffield steel (crucible and stainless). The utility of these things was inherent in their practical functions. By the latter part of the 19th century, the bourgeois house contained a home that had been remodeled by conspicuous consumption. Here, Benjamin argues, the goods were bought to display wealth (discretionary income), rather than for their practical utility. The bourgeoisie had transposed the wares of the shop window to the sitting room, where the clutter of display signaled bourgeois success (see Culture and Anarchy, 1869).

Two spatial constructs manifest the bourgeois mentality: (i) the shop-window display, and (ii) the sitting room. In English, the term "sitting-room culture" is synonymous for "bourgeois mentality", a "philistine" cultural perspective from the Victorian Era (1837–1901), especially characterized by the repression of emotion and of sexual desire; and by the construction of a regulated social-space where "propriety" is the key personality trait desired in men and women.

Nonetheless, from such a psychologically constricted worldview, regarding the rearing of children, contemporary sociologists claim to have identified "progressive" middle-class values, such as respect for non-conformity, self-direction, autonomy, gender equality, and the encouragement of innovation; as in the Victorian Era, the transposition to the US of the bourgeois system of social values has been identified as a requisite for employment success in the professions.

Bourgeois values are dependent on rationalism, which began with the economic sphere and moves into every sphere of life which is formulated by Max Weber. The beginning of rationalism is commonly called the Age of Reason. Much like the Marxist critics of that period, Weber was concerned with the growing ability of large corporations and nations to increase their power and reach throughout the world.

Satire and criticism in art

Beyond the intellectual realms of political economy, history, and political science that discuss, describe, and analyze the bourgeoisie as a social class, the colloquial usage of the sociological terms bourgeois and bourgeoise describe the social stereotypes of the old money and of the nouveau riche, who is a politically timid conformist satisfied with a wealthy, consumerist style of life characterized by conspicuous consumption and the continual striving for prestige. This being the case, the cultures of the world describe the philistinism of the middle-class personality, produced by the excessively rich life of the bourgeoisie, is examined and analyzed in comedic and dramatic plays, novels, and films (see Authenticity).

The term bourgeoisie has been used as a pejorative and a term of abuse since the 19th century, particularly by intellectuals and artists.

Theater

Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (The Would-be Gentleman, 1670) by Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin), is a comedy-ballet that satirises Monsieur Jourdain, the prototypical nouveau riche man who buys his way up the social-class scale, to realise his aspirations of becoming a gentleman, to which end he studies dancing, fencing, and philosophy, the trappings and accomplishments of a gentleman, to be able to pose as a man of noble birth, someone who, in 17th-century France, was a man to the manner born; Jourdain's self-transformation also requires managing the private life of his daughter, so that her marriage can also assist his social ascent.

Literature

Buddenbrooks (1901), by Thomas Mann (1875–1955), chronicles the moral, intellectual, and physical decay of a rich family through its declines, material and spiritual, in the course of four generations, beginning with the patriarch Johann Buddenbrook Sr. and his son, Johann Buddenbrook Jr., who are typically successful German businessmen; each is a reasonable man of solid character.

Yet, in the children of Buddenbrook Jr., the materially comfortable style of life provided by the dedication to solid, middle-class values elicits decadence: The fickle daughter, Toni, lacks and does not seek a purpose in life; son Christian is honestly decadent, and lives the life of a ne'er-do-well; and the businessman son, Thomas, who assumes command of the Buddenbrook family fortune, occasionally falters from middle-class solidity by being interested in art and philosophy, the impractical life of the mind, which, to the bourgeoisie, is the epitome of social, moral, and material decadence.

Babbitt (1922), by Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951), satirizes the American bourgeois George Follansbee Babbitt, a middle-aged realtor, booster, and joiner in the Midwestern city of Zenith, who – despite being unimaginative, self-important, and hopelessly conformist and middle-class – is aware that there must be more to life than money and the consumption of the best things that money can buy. Nevertheless, he fears being excluded from the mainstream of society more than he does living for himself, by being true to himself – his heart-felt flirtations with independence (dabbling in liberal politics and a love affair with a pretty widow) come to naught because he is existentially afraid.

Yet, George F. Babbitt sublimates his desire for self-respect, and encourages his son to rebel against the conformity that results from bourgeois prosperity, by recommending that he be true to himself:

Don't be scared of the family. No, nor all of Zenith. Nor of yourself, the way I've been.

Films

Many of the satirical films by the Spanish film director Luis Buñuel (1900–1983) examine the mental and moral effects of the bourgeois mentality, its culture, and the stylish way of life it provides for its practitioners.

- L'Âge d'or (The Golden Age, 1930) illustrates the madness and self-destructive hypocrisy of bourgeois society.

- Belle de Jour (Beauty of the day, 1967) tells the story of a bourgeois wife who is bored with her marriage and decides to prostitute herself.

- Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972) explores the timidity instilled by middle-class values.

- Cet obscur objet du désir (That Obscure Object of Desire, 1977) illuminates the practical self-deceptions required for buying love as marriage.