First contact is a common theme in science fiction about the first meeting between humans and extraterrestrial life, or of any sentient species' first encounter with another one, given they are from different planets or natural satellites. It is closely related to the anthropological idea of first contact.

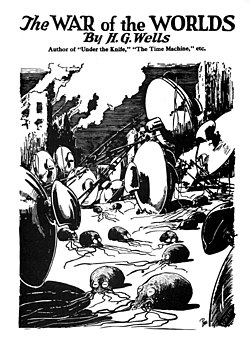

Popularized by the 1897 book The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, the concept was commonly used throughout the 1950s and 60s, often as an allegory for Soviet infiltration and invasion. The 1960s American television series Star Trek introduced the concept of the "Prime Directive", a regulation intended to limit the negative consequences of first contact.

Although there are a variety of circumstances under which first contact can occur, including indirect detection of alien technology, it is often portrayed as the discovery of the physical presence of an extraterrestrial intelligence. As a plot device, first contact is frequently used to explore a variety of themes.

History

Murray Leinster's 1945 novelette "First Contact" is the best known science fiction story which is specifically devoted to the "first contact" per se, although Leinster used the term in this sense earlier, in his 1935 story "Proxima Centauri".

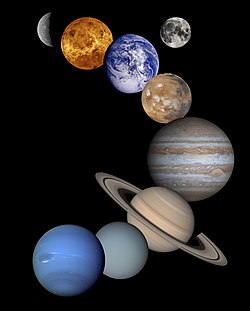

The idea of humans encountering an extraterrestrial intelligence

for the first time dates back to the second century AD, where it is

presented in the novel A True Story by Lucian of Samosata. The 1752 novel Le Micromégas by Voltaire depicts a visit of an alien from a planet circling Sirius to the Solar System. Micromegas, being 120,000 royal feet

(38.9 km) tall, first arrives at Saturn, where he befriends a

Saturnian. They both eventually reach the Earth, where using a

magnifying glass, they discern humans, and eventually engage in

philosophical disputes with them. While superficially it may be

classified as an early example of science fiction, the aliens are used

only as a technique to involve outsiders to comment on Western

civilization, a trope popular at the times.

Traditionally the origin of the trope of conflict of humans with an alien intelligent species is attributed to The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, in which Martians mount a global invasion of Earth. Still, there are earlier examples, such as the 1888 novel Les Xipéhuz,

a classic of French science fiction. It depicts the struggle of

prehistoric humans with an apparently intelligent but profoundly alien

inorganic life form. However in the latter novel it is unclear whether

the Xipéhuz arrived from the outer space or originated on the Earth.

Throughout the 1950s, stories involving first contact were common

in the United States, and typically involved conflict. Professor of

Communication Victoria O'Donnell writes that these films "presented indirect expressions of anxiety about the possibility of a nuclear holocaust

or a Communist invasion of America. These fears were expressed in

various guises, such as aliens using mind control, monstrous mutants

unleashed by radioactive fallout,

radiation's terrible effects on human life, and scientists obsessed

with dangerous experiments." Most films of this kind have an optimistic

ending. She reviewed four major topics in these films: (1)

Extraterrestrial travel, (2) alien invasion and infiltration, (3)

mutants, metamorphosis, and resurrection of extinct species, and (4) near annihilation or the end of the Earth.

The 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still was one of the first works to portray first contact as an overall beneficial event.

While the character of Klaatu is primarily concerned with preventing

conflicts spreading from Earth, the film warns of the dangers of nuclear war. Based on the 1954 serialized novel, the 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers depicts an alien infiltration, with the titular Body Snatchers overtaking the fiction town of Santa Mira. Similarly to The Day the Earth Stood Still, Invasion of the Body Snatchers reflects contemporary fears in the United States, particularly the fear of communist infiltration and takeover.

Childhood's End by Arthur C. Clarke depicts a combination of positive and negative effects from first contact: while utopia is achieved across the planet, humanity becomes stagnant, with Earth under the constant oversight of the Overlords. Stanisław Lem's 1961 novel Solaris depicts communication with an extraterrestrial intelligence as a futile endeavor, a common theme in Lem's works.

The 21st episode of Star Trek, "The Return of the Archons", introduced the Prime Directive, created by producer and screenwriter Gene L. Coon.[15] Since its creation, the Prime Directive has become a staple of the Star Trek franchise, and the concept of a non-interference directive has become common throughout science fiction.

The 1977 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind depicts first contact as a long and laborious process, with communication only being achieved at the end of the film. In Rendezvous with Rama, communication is never achieved.

In 1985, Carl Sagan published the novel Contact. The book deals primarily with the challenges inherent to determining first contact, as well as the potential responses to the discovery of an extraterrestrial intelligence. In 1997, the book was made into a movie.

The 1996 novel The Sparrow starts with the discovery of an artificial radio signal, though it deals mainly with the issue of faith. The Arrival (1996), Independence Day, and Star Trek: First Contact were released in 1996. The Arrival

portrays both an indirect first contact through the discovery of a

radio signal, as well as an alien infiltration similar to that of Invasion of the Body Snatchers; Independence Day portrays an alien invasion similar in theme and tone to The War of the Worlds; and Star Trek: First Contact portrays first contact as a beneficial and peaceful event that ultimately led to the creation of the United Federation of Planets.

The 1994 video game XCOM: UFO Defense is a strategy game that depicts an alien invasion, although first contact technically occurs prior to the game's start. The Halo and Mass Effect franchises both have novels that detail first contact events. Mass Effect: Andromeda has multiple first contacts, as it takes place in the Andromeda Galaxy.

The Chinese novel The Three-Body Problem, first published in 2006 and translated into English in 2014, presents first contact as being achieved through the reception of a radio signal. The Dark Forest, published in 2008, introduced the dark forest hypothesis based on Thomas Hobbes' description of the "natural condition of mankind", although the underlying concept dates back to "First Contact".

The 2016 film Arrival, based on the 1998 short story "Story of Your Life",

depicts a global first contact, with 12 "pods" establishing themselves

at various locations on Earth. With regard to first contact, the film

focuses primarily on the linguistic challenges inherent in first contact, and the film's plot is driven by the concept of linguistic relativity and the various responses of the governments.

The 2021 novel Project Hail Mary depicts an unintended first contact scenario when the protagonist, Ryland Grace, encounters an alien starship while on a scientific mission to Tau Ceti.

Types and themes

Due to the broad definition of first contact, there are a number of variations of the methods that result in first contact and the nature of the subsequent interaction. Variations include: positive vs. negative outcome of the first contact, actual meetings vs. interception of alien messages, etc.

Alien invasion

The idea of an alien invasion is one of the earliest and most common

portrayals of a first contact scenario, being popular since The War of the Worlds. During the Cold War,

films depicting alien invasions were common. The depiction of the

aliens tended to reflect the American conception of the Soviet Union at

the time, with infiltration stories being a variation of the theme.

Alien artifacts

A Bracewell probe

is any form of probe of extraterrestrial origin, and such technology

appears in first contact fiction. Initially hypothesized in 1960 by Ronald N. Bracewell, a Bracewell probe is a form of alien artifact that would permit real–time communication. A Big Dumb Object is a common variation of the Bracewell probe, primarily referring to megastructures such as ringworlds,

but also relatively smaller objects that are either located on the

surface of planets or natural satellites, or transiting through the

solar system (such as Rama in Rendezvous with Ramaby Arthur Clarke (1973)). A famous example is the 1968 2001: A Space Odyssey, where mysterious black "Monoliths" enhance the technological progress of humanoids and other civilizations.

A number of stories involve finding an alien spacecraft, either

in the space or on a surface of the planet, with various consequences, Rendezvous with Rama being a classic example.

Communication with alien intelligence

Many science fiction stories deal with the issues of communications.

First contact is a recurring theme in the works of Polish writer Stanisław Lem. The majority of his "first contact" stories, including his first published science fiction story, The Man from Mars (1946) and his last work of fiction, Fiasco (1986), portray the mutual understanding of a human and alien intelligences as ultimately impossible. These works criticize "the myth of cognitive universality".

Message from space

The "first contact" may originate from the detection of an extraterrestrial signal ("message from space"). In broader terms, the presence of an alien civilization may be deduced from a technosignature, which is any of a variety of detectable spectral signatures that indicate the presence or effects of technology. The occasional search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) began with the advent of radio, which was addressed in science fiction as well. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

mentions a 1864 French story "Qu'est-ce qu'ils peuvent bien nous

dire?", where humans detect a signal from Mars. Stories of this type

became numerous by 1950s. The systematic search for technosignatures began in 1960 with Project Ozma.

Alien languages

Apart from telepathy,

languages are the most common form of interpersonal communication with

aliens, and many science fiction stories deal with language issues.

While various nonlinguistic forms of communication are described as

well, such as communication via mathematics, pheromones, etc., the

distinction of linguistic vs. non-linguistic, is rather semantic: in the

majority of cases all boils down to some form of decoding/encoding of

information.

While space operas bypass the issue by either making aliens speak English perfectly, or resorting to an "universal translator", in most hard science fiction

humans usually have difficulties in talking to aliens, which may lead

to misunderstanding of various level of graveness, even leading to a

war.

Jonathan Vos Post analyzed various issues related to understanding alien languages.

Ethics of first contact

Many

notable writers have considered how humans are supposed to treat the

aliens when we meet them. One idea is that the humans should avoid the

interference in the development of alien civilizations. A notable

example of this is the Prime Directive of Star Trek, a major part of its considerable cultural influence. However, the Directive often proves to be unworkable.

Over time, the Directive has developed from its clear and

straightforward formulation to a loosely defined, aspirational

principle. Evolving from a series of bad experiences coming from the

"interventionist" approach in early episodes, the Prime Directive was

initially presented as an imperative. However, it is often portrayed as

neither the primary concern, nor imperative.

In Soviet science fiction there was a popular concept of "progressors", Earth agents working clandestinely in less advanced civilizations for their betterment, following the ideas of Communism (portrayed as already victorious on Earth). The term was introduced in the Noon Universe of the Strugatsky brothers. The Strugatskis' biographer, writing under the pen name Ant Skalandis, considered the concept as a major novelty in social science fiction.

In the Strugatskis' later works the powerful organization КОМКОН

(COMCON, Commission for Contacts), in charge of progressorship, was

tasked with counteracting the work of suspected alien progressors on the

Earth. Strugatski's novels related to the subject reject the idea of

the "export of revolution". In his report "On serious shortcomings in the publication of science fiction literature", Alexander Yakovlev,

a Soviet Communist Party functionary in charge of propaganda,

complained that Strugatskis had alleged the futility of the Communist

intervention into fascism on an alien planet.

Notable examples

The Day the Earth Stood Still

Based on the 1940 short story "Farewell to the Master", The Day the Earth Stood Still depicts the arrival of a single alien, Klaatu, and a robot, Gort, in a flying saucer, which lands in Washington, D.C. In the film, humanity's response to first contact is hostility, demonstrated both at the beginning when Klaatu is wounded, and when he is killed near the end.

First contact is used as an example of a global issue that is

ignored in favor of continuing international competition, with the

decision by the United States government to treat Klaatu as a security

threat and eventually enact martial law in Washington, D.C. being allegorical for the Second Red Scare.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a 1977 American science fiction drama film written and directed by Steven Spielberg, starring Richard Dreyfuss, Melinda Dillon, Teri Garr, Bob Balaban, Cary Guffey, and François Truffaut. The film depicts the story of Roy Neary, an everyday blue-collar worker in Indiana, whose life changes after an encounter with an unidentified flying object (UFO), and Jillian, a single mother whose three-year-old son was abducted by a UFO.

In December 2007, it was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. A Special Edition was released theatrically in 1980. Spielberg agreed to create this edition to add more scenes that they had been unable to include in the original release, with the studio demanding a controversial scene depicting the interior of the extraterrestrial mothership. Spielberg's dissatisfaction with the altered ending scene led to a third version, the Director's Cut on VHS and LaserDisc in 1998 (and later DVD and Blu-ray). It is the longest version, combining Spielberg's favorite elements from both previous editions but removing the scenes inside the mothership. The film was later remastered in 4K and was then re-released in theaters in 2017 for its 40th anniversary.Contact

Initially conceived of as a film, the 1985 novel Contact, written by American astronomer Carl Sagan, depicts the reception of a radio signal from the star Vega.

Two-way communication is achieved with the construction of a Machine,

the specifications of which are included in the message. In 1997, a film adaptation was released.

Star Trek

Within the Star Trek franchise, first contact is a central part of the operations of Starfleet.[63] While primarily depicted in the television shows, it has also been in a majority of the movies. The Prime Directive is one of the foundational regulations regarding first contact in Star Trek, and has been portrayed in every television series. Despite its importance, it is frequently violated.

Star Trek: The Original Series

In the original pilot episode for Star Trek, the crew of the USS Enterprise encounters the Talosians, subterranean humanoids with telepathic abilities,

when attempting to rescue the survivors of a crash. While the episode

wasn't broadcast in its entirety until 1988, it was incorporated into

the first-season two-part episode "The Menagerie".

The Prime Directive, also known as Starfleet General Order 1, was introduced in the 21st episode "The Return of the Archons".

In–universe, it is intended to prevent unintended negative consequences

from first contact with technologically inferior societies,

particularly those that lack faster-than-light travel.

Star Trek: The Next Generation

"Encounter at Farpoint", the pilot episode for Star Trek: The Next Generation, depicts Federation first contact with the Q Continuum, although this encounter was only included later in production.

The Prime Directive is the center of multiple episodes in the series, including "Who Watches the Watchers" and "First Contact". In both episodes, Captain Jean-Luc Picard is forced to break the Prime Directive.

Star Trek: First Contact

Released in 1996, Star Trek: First Contact portrays first contact between Humans and Vulcans at the end of the film. This event leads to the formation of the United Federation of Planets.

The War of the Worlds

The War of the Worlds is a science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells. It was written between 1895 and 1897, and serialised in Pearson's Magazine in the UK and Cosmopolitan magazine in the US in 1897. The full novel was first published in hardcover in 1898 by William Heinemann. The War of the Worlds is one of the earliest stories to detail a conflict between humankind and an extraterrestrial race. The novel is the first-person narrative of an unnamed protagonist in Surrey and his younger brother who escapes to Tillingham in Essex as London and Southern England are invaded by Martians. It is one of the most commented-on works in the science fiction canon.