Poster for the 1960 film adaptation of H. G. Wells' story

Time travel is a common theme in fiction and has been depicted in a variety of media, such as literature, television, film, and advertisements.

The concept of time travel by mechanical means was popularized in H. G. Wells' 1895 story, The Time Machine. In general, time travel stories focus on the consequences of traveling into the past or the future.

The central premise for these stories oftentimes involves changing

history, either intentionally or by accident, and the ways by which

altering the past changes the future and creates an altered present or

future for the time traveler when they return home.

Some stories focus solely on the paradoxes and alternate timelines that

come with time travel, rather than time traveling itself.

They often provide some sort of social commentary, as time travel

provides a "necessary distancing effect" that allows science fiction to

address contemporary issues in metaphorical ways.

Time travel in modern fiction is sometimes achieved by space and time warps, stemming from the scientific theory of general relativity. Stories from antiquity often featured time travel into the future through a time slip brought on by traveling or sleeping, or in other cases, time travel into the past through supernatural means, for example brought on by angels or spirits.

Time travel themes

Changing the past

The idea of changing the past is logically contradictory, and results in a grandfather paradox. Paul J. Nahin,

who has written extensively on the topic of time travel in fiction,

states that "[e]ven though the consensus today is that the past cannot

be changed, science fiction writers have used the idea of changing the

past for good story effect". Time travel to the past and precognition without the ability to change events may result in causal loops.

The possibility of characters inadvertently or intentionally

changing the past also gave rise to the idea of "time police", people

tasked with preventing such changes from occurring by themselves

engaging in time travel to rectify such changes.

Alternative future, history, timelines, and dimensions

An alternative future or alternate future is a possible future that never comes to pass, typically when someone travels back into the past and alters it so that the events of the alternative future cannot occur, or when a communication from the future to the past effected a change that alters the future.

Alternative histories may exist "side by side", with the time traveler

actually arriving at different dimensions as he changes time.

Butterfly effect

The butterfly effect is the notion that small events can have large, widespread consequences. The term describes events observed in chaos theory where a very small change in initial conditions results in vastly different outcomes. The term was coined by mathematician Edward Lorenz years after the phenomenon was first described.

The butterfly effect has found its way into popular imagination. For example, in Ray Bradbury's 1952 short story A Sound of Thunder, the killing of a single insect millions of years in the past drastically changes the world, and in the 2004 film The Butterfly Effect, the protagonist's small changes to their past results in extreme changes.

Communication from the future

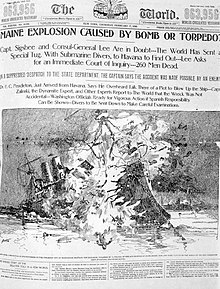

In literature, communication from the future as a plot device is encountered in various science fiction and fantasy stories. Forrest J. Ackerman

noted in his 1973 anthology of the best fiction of the year that "[t]he

theme of getting hold of tomorrow's newspaper is a recurrent one". An early example of this device can be found in the H.G. Wells 1932 short story "The Queer Story of Brownlow's Newspaper", which tells the tale of a man who receives such a paper from 40 years in the future. The 1944 film It Happened Tomorrow also employs this device,

with the protagonist receiving the next day's newspaper from an elderly

colleague (who is possibly a ghost). Ackerman's anthology also

highlights a short story by Robert Silverberg, "What We Learned From This Morning's Newspaper". In that story, a block of homeowners wake to discover that on November 22, they have received the New York Times for the coming December 1.

As characters learn of future events affecting them through a newspaper

delivered a week early, the ultimate effect is that this "so upsets the

future that spacetime is destroyed". The television series Early Edition, inspired by the film It Happened Tomorrow, also revolved around a character who daily received the next day's newspaper, and sought to change some event therein forecast to happen.

A newspaper from the future can be a fictional edition of a real newspaper, or an entirely fictional newspaper. John Buchan's novel The Gap in the Curtain, is similarly premised on a group of people being enabled to see, for a moment, an item in Times newspaper from one year in the future. During the Swedish general election of 2006, the Swedish liberal party used election posters which looked like news items, called Framtidens nyheter ("News of the future"), featuring things that Sweden in the future had become what the party wanted.

A communication from the future raises questions about the ability of humans to control their destiny.

If the recipient is allowed to presume that the future is malleable,

and if the future forecast affects them in some way, then this device

serves as a convenient explanation of their motivations. In It Happened Tomorrow,

the events that are described in the newspaper do come to pass, and the

protagonist's efforts to avoid those events set up circumstances which

instead cause them to come about. By contrast, in Early Edition,

the protagonist is able to successfully prevent catastrophes predicted

in the newspaper, although if the protagonist does nothing, these

catastrophes do come about.

Where such a device is used, the source of the future news may

not be explained, leaving it open to the reader or watcher to imagine

that it might be technology, magic, an act of a god etc.

In the H.G. Wells story, the author writes of the newspaper that

"apparently it had been delivered not by the postman, but by some other

hand". As in It Happened Tomorrow and Early Edition,

no explanation is offered for the source of the future news. Ackerman

suggests that "[t]he longer that authors mush on with the tale of... the

next-week's-newspaper-now, the more difficult it becomes to pull a new

rarebit out of the hat".

Precognition

Precognition has been explored as a form of time travel in fiction. Author J. B. Priestley wrote of it both in fiction and non-fiction, analyzing testimonials of precognition and other "temporal anomalies" in his book Man and Time.

His books include time travel to the future through dreaming, which

upon waking up results in memories from the future. Such memories, he

writes, may also lead to the feeling of déjà vu, that the present events have already been experienced, and are now being re-experienced. Infallible precognition, which describes the future as it truly is, leads to causal loops, a form of which is explored in Newcomb's paradox. The film 12 Monkeys heavily deals with themes of predestination and the Cassandra complex, where the protagonist who travels back in time explains that he can't change the past.

Time loop

A "time loop" or "temporal loop" is a plot device

in which periods of time are repeated and re-experienced by the

characters, and there is often some hope of breaking out of the cycle of

repetition. Time loops are sometimes referred to as causal loops,

but these two concepts are distinct. Although similar, causal loops are

unchanging and self-originating, whereas time loops are constantly

resetting. In a time loop when a certain condition is met, such as a

death of a character or a clock reaching a certain time, the loop starts

again, with one or more characters retaining the memories from the

previous loop. Stories with time loops commonly center on the character learning from each successive loop through time.

Time paradox

Many time travel works explore the topic of disrupting causality

leading to time paradoxes. One of the most commonly referred to in time

travel literature is known as the grandfather paradox.

Many works of fiction explore what would happen if a time traveler

went back in time and changed the past, for example if they killed their

own grandparents.

Time slip

A time slip is a plot device used in fantasy and science fiction in which a person, or group of people, seem to travel through time by unknown means for a period of time.

The idea of a time slip has been utilized by a number of science

fiction and fantasy writers popularized at the end of the 19th century

by Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, having considerable influence on later writers. This is one of the main plot devices of time travel stories, the other being a time machine.

The difference is that in time slip stories, the protagonist typically

has no control and no understanding of the process (which is often never

explained at all) and is either left marooned in a past time and must

make the best of it, or is eventually returned by a process as

unpredictable and uncontrolled. The plot device is also popular in children's literature.

Time slips featuring a child and a realistic depiction of an earlier period enjoyed a vogue in the UK in the mid-20th century. Successful examples include Alison Uttley's A Traveller in Time (1939) going back to the time of Mary, Queen of Scots; Philippa Pearce's Tom's Midnight Garden (1958) returning to the 1880s and 1890s; Barbara Sleigh's Jessamy (1967) and Penelope Farmer's Charlotte Sometimes, both slipping back to the period of the First World War; Ruth Park's Playing Beatie Bow (1980), where the slip in Sydney, Australia, is to the squalor of 1873; and Helen Cresswell's Moondial, where three times periods are involved (1988, also televised).

Time tourism

A "distinct subgenre" of stories explore the possibility that time travel might be used as a means of tourism, with travelers curious to visit periods or events such as the Victorian Era, Crucifixion of Christ, or some point where dinosaurs could be watched (or hunted by big game hunters), or to meet historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln or Ludwig van Beethoven. This theme can be addressed from two directions. An early example of present-day tourists travelling back to the past is Ray Bradbury's A Sound of Thunder (1952), in which the protagonists are big game hunters who travel to the distant past to hunt dinosaurs. An early example of the other type, in which tourists from the future visit the present, is Catherine L. Moore and Henry Kuttner's Vintage Season (1946), a story which was selected for inclusion in Volume Two of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame collection.

Immortality

Instances of immortality are prevalent in time travel fiction. Oxford

defines immortality as "the ability to live forever; eternal life." A

distinct sub-thematic characteristic is warnings of said time-traveling

immortals to other characters about the dangers of time travel. Some

examples are 4th dimensional beings from Rick and Morty, Professor Paradox from Ben 10, and the Doctor from Doctor Who.

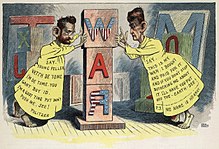

Time war

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

describes a time war as a fictional war that is "fought across time,

usually with each side knowingly using time travel ... in an attempt to

establish the ascendancy of one or another version of history". Time

wars are also known as "change wars" and "temporal wars".

P. Nahin compiles a variety of examples of fictional works that raise issues framed as arising in a time war:

Consider this passage from The Fall of Chronopolis (Bayley), a novel about a "time-war." Just after the detection of temporal invaders, we read of them that "They had come in from the future at high speed, too fast for defensive time-blocks to be set up, and had only been detected by ground-based stations deep in historical territory. If the target was to alter past events—the usual strategy in a time-war—then the empire's chronocontinuity would be significantly interfered with." And in Time of the Fox (Costello), American physicists battle KGB physicists in a war of time travelers in the past, each side attempting to change history to its advantage. In this novel the history changers isolate themselves from all the alterations taking place outside of their Time Lab, and they compare their stored historical records with those of external libraries. That allows the staff historian to adjust for each new round of changes. As the historian explains, outside of the Time Lab "History might change, but here [in the Time Lab] the past lives on."

In a novel of a galaxy-wide confrontation between humans and androids—Time and Again (Simak)—the use of time travel to alter history is central: "A war in time ... would reach back to win its battles. It would strike at points in time and space which would not even know that there was a war. It could, logically, go back to the silver mines of Athens, to the horse and chariot of Thut- mosis III, to the sailing of Columbus. ... It would twist the fabric of the past."

Hitler and World War II

In Western fiction, one common use of time travel technology is to travel back in time and attempt to kill Adolf Hitler in an attempt to avoid World War II and the Holocaust.

Fiction that applies the Novikov self-consistency principle

that the past can't be changed results in plots where attempts to

assassinate Hitler or avert the war are destined to fail, or where they

actually result in the rise of Hitler as history records it. Fiction that does allow the past to be changed often explores the unintended consequences of time travel or the butterfly effect, which result in Germany and Japan winning World War II. This outcome is also explored in parallel world fiction such as The Man in the High Castle.