Human iron metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that maintain human homeostasis of iron at the systemic and cellular level. Iron is both necessary to the body and potentially toxic. Controlling iron levels in the body is a critically important part of many aspects of human health and disease.

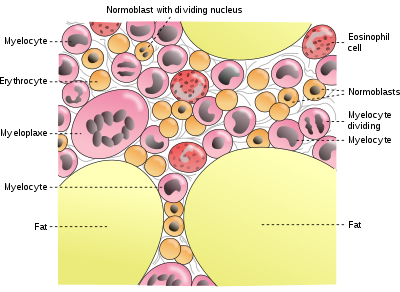

Hematologists have been especially interested in systemic iron metabolism because iron is essential for red blood cells, where most of the human body's iron is contained. Understanding iron metabolism is also important for understanding diseases of iron overload, such as hereditary hemochromatosis, and iron deficiency, such as iron deficiency anemia.

Importance of iron regulation

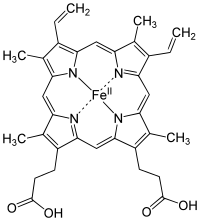

Iron is an essential bioelement for most forms of life, from bacteria to mammals. Its importance lies in its ability to mediate electron transfer. In the ferrous state, iron acts as an electron donor, while in the ferric state it acts as an acceptor. Thus, iron plays a vital role in the catalysis of enzymatic reactions that involve electron transfer (reduction and oxidation, redox). Proteins can contain iron as part of different cofactors, such as iron-sulfur clusters (Fe-S) and heme groups, both of which are assembled in mitochondria.

Cellular respiration

Human cells require iron in order to obtain energy as ATP from a multi-step process known as cellular respiration, more specifically from oxidative phosphorylation at the mitochondrial cristae. Iron is present in the iron-sulfur clusters and heme groups of the electron transport chain proteins that generate a proton gradient that allows ATP synthase to synthesize ATP (chemiosmosis).

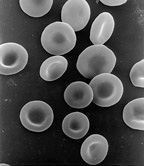

Heme groups are part of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells that serves to transport oxygen from the lungs to other tissues. Heme groups are also present in myoglobin to store and diffuse oxygen in muscle cells.

Oxygen transport

The human body needs iron for oxygen transport. Oxygen (O2) is required for the functioning and survival of nearly all cell types. Oxygen is transported from the lungs to the rest of the body bound to the heme group of hemoglobin in red blood cells. In muscles cells, iron binds oxygen to myoglobin, which regulates its release.

Toxicity

Iron is also potentially toxic. Its ability to donate and accept electrons means that it can catalyze the conversion of hydrogen peroxide into free radicals. Free radicals can cause damage to a wide variety of cellular structures, and ultimately kill the cell.

Iron bound to proteins or cofactors such as heme is safe. Also, there are virtually no truly free iron ions in the cell, since they readily form complexes with organic molecules. However, some of the intracellular iron is bound to low-affinity complexes, and is termed labile iron or "free" iron. Iron in such complexes can cause damage as described above.

To prevent that kind of damage, all life forms that use iron bind the iron atoms to proteins. This binding allows cells to benefit from iron while also limiting its ability to do harm. Typical intracellular labile iron concentrations in bacteria are 10-20 micromolar, though they can be 10-fold higher in anaerobic environment, where free radicals and reactive oxygen species are scarcer. In mammalian cells, intracellular labile iron concentrations are typically smaller than 1 micromolar, less than 5 percent of total cellular iron.

Bacterial protection

In response to a systemic bacterial infection, the immune system initiates a process known as iron withholding. If bacteria are to survive, then they must obtain iron from their environment. Disease-causing bacteria do this in many ways, including releasing iron-binding molecules called siderophores and then reabsorbing them to recover iron, or scavenging iron from hemoglobin and transferrin. The harder they have to work to get iron, the greater a metabolic price they must pay. That means that iron-deprived bacteria reproduce more slowly. So our control of iron levels appears to be an important defense against many bacterial infections. Certain bacteria species have developed strategies to circumvent that defense, TB causing bacteria can reside within macrophages, which present an iron rich environment and Borrelia burgdorferi uses manganese in place of iron. People with increased amounts of iron, as, for example, in hemochromatosis, are more susceptible to some bacterial infections.

Although this mechanism is an elegant response to short-term bacterial infection, it can cause problems when it goes on so long that the body is deprived of needed iron for red cell production. Inflammatory cytokines stimulate the liver to produce the iron metabolism regulator protein hepcidin, that reduces available iron. If hepcidin levels increase because of non-bacterial sources of inflammation, like viral infection, cancer, auto-immune diseases or other chronic diseases, then the anemia of chronic disease may result. In this case, iron withholding actually impairs health by preventing the manufacture of enough hemoglobin-containing red blood cells.

Body iron stores

Most well-nourished people in industrialized countries have 4 to 5 grams of iron in their bodies (∼38 mg iron/kg body weight for women and ∼50 mg iron/kg body for men). Of this, about 2.5 g is contained in the hemoglobin needed to carry oxygen through the blood (around 0.5 mg of iron per mL of blood), and most of the rest (approximately 2 grams in adult men, and somewhat less in women of childbearing age) is contained in ferritin complexes that are present in all cells, but most common in bone marrow, liver, and spleen. The liver stores of ferritin are the primary physiologic source of reserve iron in the body. The reserves of iron in industrialized countries tend to be lower in children and women of child-bearing age than in men and in the elderly. Women who must use their stores to compensate for iron lost through menstruation, pregnancy or lactation have lower non-hemoglobin body stores, which may consist of 500 mg, or even less.

Of the body's total iron content, about 400 mg is devoted to cellular proteins that use iron for important cellular processes like storing oxygen (myoglobin) or performing energy-producing redox reactions (cytochromes). A relatively small amount (3–4 mg) circulates through the plasma, bound to transferrin. Because of its toxicity, free soluble iron is kept in low concentration in the body.

Iron deficiency first affects the storage of iron in the body, and depletion of these stores is thought to be relatively asymptomatic, although some vague and non-specific symptoms have been associated with it. Since iron is primarily required for hemoglobin, iron deficiency anemia is the primary clinical manifestation of iron deficiency. Iron-deficient people will suffer or die from organ damage well before their cells run out of the iron needed for intracellular processes like electron transport.

Macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system store iron as part of the process of breaking down and processing hemoglobin from engulfed red blood cells. Iron is also stored as a pigment called hemosiderin, which is an ill-defined deposit of protein and iron, created by macrophages where excess iron is present, either locally or systemically, e.g., among people with iron overload due to frequent blood cell destruction and the necessary transfusions their condition calls for. If systemic iron overload is corrected, over time the hemosiderin is slowly resorbed by the macrophages.

Mechanisms of iron regulation

Human iron homeostasis is regulated at two different levels. Systemic iron levels are balanced by the controlled absorption of dietary iron by enterocytes, the cells that line the interior of the intestines, and the uncontrolled loss of iron from epithelial sloughing, sweat, injuries and blood loss. In addition, systemic iron is continuously recycled. Cellular iron levels are controlled differently by different cell types due to the expression of particular iron regulatory and transport proteins.

Systemic iron regulation

Dietary iron uptake

The absorption of dietary iron is a variable and dynamic process. The amount of iron absorbed compared to the amount ingested is typically low, but may range from 5% to as much as 35% depending on circumstances and type of iron. The efficiency with which iron is absorbed varies depending on the source. Generally, the best-absorbed forms of iron come from animal products. Absorption of dietary iron in iron salt form (as in most supplements) varies somewhat according to the body’s need for iron, and is usually between 10% and 20% of iron intake. Absorption of iron from animal products, and some plant products, is in the form of heme iron, and is more efficient, allowing absorption of from 15% to 35% of intake. Heme iron in animals is from blood and heme-containing proteins in meat and mitochondria, whereas in plants, heme iron is present in mitochondria in all cells that use oxygen for respiration.

Like most mineral nutrients, the majority of the iron absorbed from digested food or supplements is absorbed in the duodenum by enterocytes of the duodenal lining. These cells have special molecules that allow them to move iron into the body. To be absorbed, dietary iron can be absorbed as part of a protein such as heme protein or iron must be in its ferrous Fe2+ form. A ferric reductase enzyme on the enterocytes’ brush border, duodenal cytochrome B (Dcytb), reduces ferric Fe3+ to Fe2+. A protein called divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), which can transport several divalent metals across the plasma membrane, then transports iron across the enterocyte’s cell membrane into the cell. If the iron is bound to heme it is instead transported across the apical membrane by heme carrier protein 1 (HCP1).

These intestinal lining cells can then either store the iron as ferritin, which is accomplished by Fe3+ binding to apoferritin (in which case the iron will leave the body when the cell dies and is sloughed off into feces), or the cell can release it into the body via the only known iron exporter in mammals, ferroportin. Hephaestin, a ferroxidase that can oxidize Fe2+ to Fe3+ and is found mainly in the small intestine, helps ferroportin transfer iron across the basolateral end of the intestine cells. In contrast, ferroportin is post-translationally repressed by hepcidin, a 25-amino acid peptide hormone. The body regulates iron levels by regulating each of these steps. For instance, enterocytes synthesize more Dcytb, DMT1 and ferroportin in response to iron deficiency anemia. Iron absorption from diet is enhanced in the presence of vitamin C and diminished by excess calcium, zinc, or manganese.

The human body’s rate of iron absorption appears to respond to a variety of interdependent factors, including total iron stores, the extent to which the bone marrow is producing new red blood cells, the concentration of hemoglobin in the blood, and the oxygen content of the blood. The body also absorbs less iron during times of inflammation, in order to deprive bacteria of iron. Recent discoveries demonstrate that hepcidin regulation of ferroportin is responsible for the syndrome of anemia of chronic disease.

Iron recycling and loss

Most of the iron in the body is hoarded and recycled by the reticuloendothelial system, which breaks down aged red blood cells. In contrast to iron uptake and recycling, there is no physiologic regulatory mechanism for excreting iron. People lose a small but steady amount by gastrointestinal blood loss, sweating and by shedding cells of the skin and the mucosal lining of the gastrointestinal tract. The total amount of loss for healthy people in the developed world amounts to an estimated average of 1 mg a day for men, and 1.5–2 mg a day for women with regular menstrual periods. People with gastrointestinal parasitic infections, more commonly found in developing countries, often lose more. Those who cannot regulate absorption well enough get disorders of iron overload. In these diseases, the toxicity of iron starts overwhelming the body's ability to bind and store it.

Cellular iron regulation

Iron import

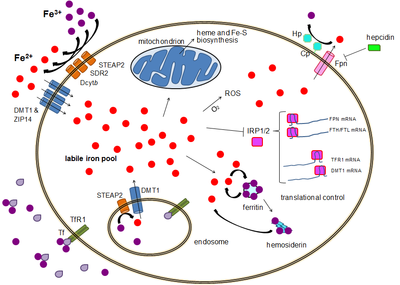

Most cell types take up iron primarily through receptor-mediated endocytosis via transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1), transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2) and GAPDH. TFR1 has a 30-fold higher affinity for transferrin-bound iron than TFR2 and thus is the main player in this process. The higher order multifunctional glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) also acts as a transferrin receptor. Transferrin-bound ferric iron is recognized by these transferrin receptors, triggering a conformational change that causes endocytosis. Iron then enters the cytoplasm from the endosome via importer DMT1 after being reduced to its ferrous state by a STEAP family reductase.

Alternatively, iron can enter the cell directly via plasma membrane divalent cation importers such as DMT1 and ZIP14 (Zrt-Irt-like protein 14). Again, iron enters the cytoplasm in the ferrous state after being reduced in the extracellular space by a reductase such as STEAP2, STEAP3 (in red blood cells), Dcytb (in enterocytes) and SDR2.

The labile iron pool

In the cytoplasm, ferrous iron is found in a soluble, chelatable state which constitutes the labile iron pool (~0.001 mM). In this pool, iron is thought to be bound to low-mass compounds such as peptides, carboxylates and phosphates, although some might be in a free, hydrated form (aqua ions).

Alternatively, iron ions might be bound to specialized proteins known as metallochaperones.

Specifically, poly-r(C)-binding proteins (PCBPs) appear to mediate transfer of free iron to ferritin (for storage) and non-heme iron enzymes (for use in catalysis). The labile iron pool is potentially toxic due to iron's ability to generate reactive oxygen species. Iron from this pool can be taken up by mitochondria via mitoferrin to synthesize Fe-S clusters and heme groups.

The storage iron pool

Iron can be stored in ferritin as ferric iron due to the ferroxidase activity of the ferritin heavy chain. Dysfunctional ferritin may accumulate as hemosiderin, which can be problematic in cases of iron overload. The ferritin storage iron pool is much larger than the labile iron pool, ranging in concentration from 0.7 mM to 3.6 mM.

Iron export

Iron export occurs in a variety of cell types, including neurons, red blood cells, macrophages and enterocytes. The latter two are especially important since systemic iron levels depend upon them. There is only one known iron exporter, ferroportin. It transports ferrous iron out of the cell, generally aided by ceruloplasmin and/or hephaestin (mostly in enterocytes), which oxidize iron to its ferric state so it can bind ferritin in the extracellular medium. Hepcidin causes the internalization of ferroportin, decreasing iron export. Besides, hepcidin seems to downregulate both TFR1 and DMT1 through an unknown mechanism. Another player assisting ferroportin in effecting cellular iron export is GAPDH. A specific post translationally modified isoform of GAPDH is recruited to the surface of iron loaded cells where it recruits apo-transferrin in close proximity to ferroportin so as to rapidly chelate the iron extruded.

The expression of hepcidin, which only occurs in certain cell types such as hepatocytes, is tightly controlled at the transcriptional level and it represents the link between cellular and systemic iron homeostasis due to hepcidin's role as "gatekeeper" of iron release from enterocytes into the rest of the body. Erythroblasts produce erythroferrone, a hormone which inhibits hepcidin and so increases the availability of iron needed for hemoglobin synthesis.

Translational control of cellular iron

Although some control exists at the transcriptional level, the regulation of cellular iron levels is ultimately controlled at the translational level by iron-responsive element-binding proteins IRP1 and especially IRP2. When iron levels are low, these proteins are able to bind to iron-responsive elements (IREs). IREs are stem loop structures in the untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNA.

Both ferritin and ferroportin contain an IRE in their 5' UTRs, so that under iron deficiency their translation is repressed by IRP2, preventing the unnecessary synthesis of storage protein and the detrimental export of iron. In contrast, TFR1 and some DMT1 variants contain 3' UTR IREs, which bind IRP2 under iron deficiency, stabilizing the mRNA, which guarantees the synthesis of iron importers.

Pathology

Iron deficiency

Functional or actual iron deficiency can result from a variety of causes. These causes can be grouped into several categories:

- Increased demand for iron, which the diet cannot accommodate.

- Increased loss of iron (usually through loss of blood).

- Nutritional deficiency. This can result due to a lack of dietary iron or consumption of foods that inhibit iron absorption. Absorption inhibition has been observed caused by phytates in bran, calcium from supplements or dairy products, and tannins from tea, although in all three of these studies the effect was small and the authors of the studies cited regarding bran and tea note that the effect will probably only have a noticeable impact when most iron is obtained from vegetable sources.

- Acid-reducing medications: Acid-reducing medications reduce the absorption of dietary iron. These medications are commonly used for gastritis, reflux disease, and ulcers. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2 antihistamines, and antacids will reduce iron metabolism.

- Damage to the intestinal lining. Examples of causes of this kind of damage include surgery involving the duodenum or diseases like Crohn's or celiac sprue which severely reduce the surface area available for absorption. Helicobacter pylori infections also reduce the availability of iron.

- Inflammation leading to hepcidin-induced restriction on iron release from enterocytes (see above).

- Is also a common occurrence in pregnant women, and in growing adolescents due to poor diets.

- Acute blood loss or acute liver cirrhosis creates a lack of transferrin therefore causing iron to be secreted from the body.

Iron overload

The body is able to substantially reduce the amount of iron it absorbs across the mucosa. It does not seem to be able to entirely shut down the iron transport process. Also, in situations where excess iron damages the intestinal lining itself (for instance, when children eat a large quantity of iron tablets produced for adult consumption), even more iron can enter the bloodstream and cause a potentially deadly syndrome of iron overload. Large amounts of free iron in the circulation will cause damage to critical cells in the liver, the heart and other metabolically active organs.

Iron toxicity results when the amount of circulating iron exceeds the amount of transferrin available to bind it, but the body is able to vigorously regulate its iron uptake. Thus, iron toxicity from ingestion is usually the result of extraordinary circumstances like iron tablet over-consumption rather than variations in diet. The type of acute toxicity from iron ingestion causes severe mucosal damage in the gastrointestinal tract, among other problems.

Excess iron has been linked to higher rates of disease and mortality. For example, breast cancer patients with low ferroportin expression (leading to higher concentrations of intracellular iron) survive for a shorter period of time on average, while high ferroportin expression predicts 90% 10-year survival in breast cancer patients. Similarly, genetic variations in iron transporter genes known to increase serum iron levels also reduce lifespan and the average number of years spent in good health. It has been suggested that mutations that increase iron absorpion, such as the ones responsible for hemochromatosis (see below), were selected for during Neolithic times as they provided a selective advantage against iron deficiency anemia. The increase in systemic iron levels becomes pathological in old age, which supports the notion that antagonistic pleiotropy or "hyperfunction" drives human aging.

Chronic iron toxicity is usually the result of more chronic iron overload syndromes associated with genetic diseases, repeated transfusions or other causes. In such cases the iron stores of an adult may reach 50 grams (10 times normal total body iron) or more. The most common diseases of iron overload are hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), caused by mutations in the HFE gene, and the more severe disease juvenile hemochromatosis (JH), caused by mutations in either hemojuvelin (HJV) or hepcidin (HAMP). The exact mechanisms of most of the various forms of adult hemochromatosis, which make up most of the genetic iron overload disorders, remain unsolved. So, while researchers have been able to identify genetic mutations causing several adult variants of hemochromatosis, they now must turn their attention to the normal function of these mutated genes.