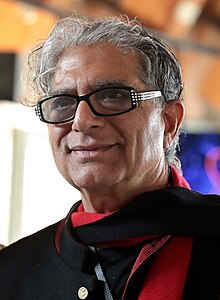

Deepak Chopra | |

|---|---|

| Born | October 22, 1946 New Delhi, British India |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Rita Chopra (m. 1970) |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Sanjiv Chopra (brother) |

| Website | Official website |

Deepak Chopra (/ˈdiːpɑːk ˈtʃoʊprə/; Hindi: [diːpək tʃoːpɽa]; born October 22, 1946) is an Indian-American author and alternative medicine advocate. A prominent figure in the New Age movement, his books and videos have made him one of the best-known and wealthiest figures in alternative medicine. His discussions of quantum healing have been characterised as technobabble – "incoherent babbling strewn with scientific terms" which drives those who actually understand physics "crazy" and as "redefining Wrong".

Chopra studied medicine in India before emigrating in 1970 to the United States, where he completed a residency in internal medicine and a fellowship in endocrinology. As a licensed physician, in 1980 he became chief of staff at the New England Memorial Hospital (NEMH).[11] In 1985, he met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and became involved in the Transcendental Meditation (TM) movement. Shortly thereafter, Chopra resigned his position at NEMH to establish the Maharishi Ayurveda Health Center. In 1993, Chopra gained a following after he was interviewed about his books on The Oprah Winfrey Show. He then left the TM movement to become the executive director of Sharp HealthCare's Center for Mind-Body Medicine. In 1996, he co-founded the Chopra Center for Wellbeing.

Chopra claims that a person may attain "perfect health", a condition "that is free from disease, that never feels pain", and "that cannot age or die". Seeing the human body as undergirded by a "quantum mechanical body" composed not of matter but energy and information, he believes that "human aging is fluid and changeable; it can speed up, slow down, stop for a time, and even reverse itself", as determined by one's state of mind. He claims that his practices can also treat chronic disease.

The ideas Chopra promotes have regularly been criticized by medical and scientific professionals as pseudoscience. The criticism has been described as ranging "from the dismissive to...damning". Philosopher Robert Carroll writes that Chopra, to justify his teachings, attempts to integrate Ayurveda with quantum mechanics. Chopra says that what he calls "quantum healing" cures any manner of ailments, including cancer, through effects that he claims are literally based on the same principles as quantum mechanics. This has led physicists to object to his use of the term "quantum" in reference to medical conditions and the human body. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has said that Chopra uses "quantum jargon as plausible-sounding hocus pocus". Chopra's treatments generally elicit nothing but a placebo response, and they have drawn criticism that the unwarranted claims made for them may raise "false hope" and lure sick people away from legitimate medical treatments.

Biography

Early life and education

Chopra was born in New Delhi, British India to Krishan Lal Chopra (1919–2001) and Pushpa Chopra. His paternal grandfather was a sergeant in the British Indian Army. His father was a prominent cardiologist, head of the department of medicine and cardiology at New Delhi's Moolchand Khairati Ram Hospital for over 25 years, and was also a lieutenant in the British army, serving as an army doctor at the front at Burma and acting as a medical adviser to Lord Mountbatten, viceroy of India. As of 2014, Chopra's younger brother, Sanjiv Chopra, is a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and on staff at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Chopra completed his primary education at St. Columba's School in New Delhi and graduated from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in 1969. He spent his first months as a doctor working in rural India, including, he writes, six months in a village where the lights went out whenever it rained. It was during his early career that he was drawn to study endocrinology, particularly neuroendocrinology, to find a biological basis for the influence of thoughts and emotions.

He married in India in 1970 before emigrating, with his wife, to the United States that same year. The Indian government had banned its doctors from sitting for the exam needed to practice in the United States. Consequently, Chopra had to travel to Sri Lanka to take it. After passing, he arrived in the United States to take up a clinical internship at Muhlenberg Hospital in Plainfield, New Jersey, where doctors from overseas were being recruited to replace those serving in Vietnam.

Between 1971 and 1977, he completed residencies in internal medicine at the Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Massachusetts, the VA Medical Center, St Elizabeth's Medical Center, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He earned his license to practice medicine in the state of Massachusetts in 1973, becoming board certified in internal medicine, specializing in endocrinology.

East Coast years

Chopra taught at the medical schools of Tufts University, Boston University, and Harvard University, and became Chief of Staff at the New England Memorial Hospital (NEMH) (later known as the Boston Regional Medical Center) in Stoneham, Massachusetts before establishing a private practice in Boston in endocrinology.

While visiting New Delhi in 1981, he met the Ayurvedic physician Brihaspati Dev Triguna, head of the Indian Council for Ayurvedic Medicine, whose advice prompted him to begin investigating Ayurvedic practices. Chopra was "drinking black coffee by the hour and smoking at least a pack of cigarettes a day". He took up Transcendental Meditation to help him stop, and as of 2006, he continued to meditate for two hours every morning and half an hour in the evening.

Chopra's involvement with TM led to a meeting in 1985 with the leader of the TM movement, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who asked him to establish an Ayurvedic health center. He left his position at the NEMH. Chopra said that one of the reasons he left was his disenchantment at having to prescribe too many drugs: "[W]hen all you do is prescribe medication, you start to feel like a legalized drug pusher. That doesn't mean that all prescriptions are useless, but it is true that 80 percent of all drugs prescribed today are of optional or marginal benefit."

He became the founding president of the American Association of Ayurvedic Medicine, one of the founders of Maharishi Ayur-Veda Products International, and medical director of the Maharishi Ayur-Veda Health Center in Lancaster, Massachusetts. The center charged between $2,850 and $3,950 per week for Ayurvedic cleansing rituals such as massages, enemas, and oil baths, and TM lessons cost an additional $1,000. Celebrity patients included Elizabeth Taylor. Chopra also became one of the TM movement's spokespeople. In 1989, the Maharishi awarded him the title "Dhanvantari of Heaven and Earth" (Dhanvantari was the Hindu physician to the gods). That year Chopra's Quantum Healing: Exploring the Frontiers of Mind/Body Medicine was published, followed by Perfect Health: The Complete Mind/Body Guide (1990).

West Coast years

In June 1993, he moved to California as executive director of Sharp HealthCare's Institute for Human Potential and Mind/Body Medicine, and head of their Center for Mind/Body Medicine, a clinic in an exclusive resort in Del Mar, California, that charged $4,000 per week and included Michael Jackson's family among its clients. Chopra and Jackson first met in 1988 and remained friends for 20 years. When Jackson died in 2009 after being administered prescription drugs, Chopra said he hoped it would be a call to action against the "cult of drug-pushing doctors, with their co-dependent relationships with addicted celebrities".

Chopra left the Transcendental Meditation movement around the time he moved to California in January 1993. Mahesh Yogi claimed that Chopra had competed for the Maharishi's position as guru, although Chopra rejected this. According to Robert Todd Carroll, Chopra left the TM organization when it "became too stressful" and was a "hindrance to his success". Cynthia Ann Humes writes that the Maharishi was concerned, and not only with regard to Chopra, that rival systems were being taught at lower prices. Chopra, for his part, was worried that his close association with the TM movement might prevent Ayurvedic medicine from being accepted as legitimate, particularly after the problems with the JAMA article. He also stated that he had become uncomfortable with what seemed like a "cultish atmosphere around Maharishi".

In 1995, Chopra was not licensed to practice medicine in California where he had a clinic. However, he did not see patients at this clinic "as a doctor" during this time. In 2004, he received his California medical license, and as of 2014 is affiliated with Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, California. Chopra is the owner and supervisor of the Mind-Body Medical Group within the Chopra Center, which in addition to standard medical treatment offers personalized advice about nutrition, sleep-wake cycles, and stress management based on mainstream medicine and Ayurveda. He is a fellow of the American College of Physicians and member of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

Alternative medicine business

Chopra's book Ageless Body, Timeless Mind: The Quantum Alternative to Growing Old was published in 1993. The book and his friendship with Michael Jackson gained him an interview on July 12 that year on Oprah. Paul Offit writes that within 24 hours Chopra had sold 137,000 copies of his book and 400,000 by the end of the week. Four days after the interview, the Maharishi National Council of the Age of Enlightenment wrote to TM centers in the United States, instructing them not to promote Chopra, and his name and books were removed from the movement's literature and health centers. Neuroscientist Tony Nader became the movement's new "Dhanvantari of Heaven and Earth".

Sharp HealthCare changed ownership in 1996 and Chopra left to set up the Chopra Center for Wellbeing with neurologist David Simon, now located at the Omni La Costa Resort and Spa in Carlsbad, California. In his 2013 book, Do You Believe in Magic?, Paul Offit writes that Chopra's business grosses approximately $20 million annually, and is built on the sale of various alternative medicine products such as herbal supplements, massage oils, books, videos and courses. A year's worth of products for "anti-ageing" can cost up to $10,000, Offit wrote. Chopra himself is estimated to be worth over $80 million as of 2014. As of 2005, according to Srinivas Aravamudan, he was able to charge $25,000 to $30,000 per lecture five or six times a month. Medical anthropologist Hans Baer said Chopra was an example of a successful entrepreneur, but that he focused too much on serving the upper-class through an alternative to medical hegemony, rather than a truly holistic approach to health.

Teaching and other roles

Chopra serves as an adjunct professor in the marketing division at Columbia Business School. He serves as adjunct professor of executive programs at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. He participates annually as a lecturer at the Update in Internal Medicine event sponsored by Harvard Medical School and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Robert Carroll writes of Chopra charging $25,000 per lecture, "giving spiritual advice while warning against the ill effects of materialism".

In 2015, Chopra partnered with businessman Paul Tudor Jones II to found JUST Capital, a non-profit firm which ranks companies in terms of just business practices in an effort to promote economic justice. In 2014, Chopra founded ISHAR (Integrative Studies Historical Archive and Repository). In 2012, Chopra joined the board of advisors for tech startup State.com, creating a browsable network of structured opinions. In 2009, Chopra founded the Chopra Foundation, a tax-exempt 501(c) organization that raises funds to promote and research alternative health. The Foundation sponsors annual Sages and Scientists conferences. He sits on the board of advisors of the National Ayurvedic Medical Association, an organization based in the United States. Chopra founded the American Association for Ayurvedic Medicine (AAAM) and Maharishi AyurVeda Products International, though he later distanced himself from these organizations. In 2005, Chopra was appointed as a senior scientist at The Gallup Organization. Since 2004, he has been a board member of Men's Wearhouse, a men's clothing distributor. In 2006, he launched Virgin Comics with his son Gotham Chopra and entrepreneur Richard Branson. In 2016, Chopra was promoted from voluntary assistant clinical professor to voluntary full clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego in their Department of Family Medicine and Public Health.

Personal life

Chopra and his wife have, as of 2013, two adult children (Gotham Chopra and Mallika Chopra) and three grandchildren. As of 2019, Chopra lives in a "health-centric" condominium in Manhattan.

Ideas and reception

Chopra believes that a person may attain "perfect health", a condition "that is free from disease, that never feels pain", and "that cannot age or die". Seeing the human body as being undergirded by a "quantum mechanical body" comprised not of matter but energy and information, he believes that "human aging is fluid and changeable; it can speed up, slow down, stop for a time, and even reverse itself", as determined by one's state of mind. He claims that his practices can also treat chronic disease.

Consciousness

Chopra speaks and writes regularly about metaphysics, including the study of consciousness and Vedanta philosophy. He is a philosophical idealist, arguing for the primacy of consciousness over matter and for teleology and intelligence in nature – that mind, or "dynamically active consciousness", is a fundamental feature of the universe.

In this view, consciousness is both subject and object. It is consciousness, he writes, that creates reality; we are not "physical machines that have somehow learned to think...[but] thoughts that have learned to create a physical machine". He argues that the evolution of species is the evolution of consciousness seeking to express itself as multiple observers; the universe experiences itself through our brains: "We are the eyes of the universe looking at itself". He has been quoted as saying: "Charles Darwin was wrong. Consciousness is key to evolution and we will soon prove that." He opposes reductionist thinking in science and medicine, arguing that we can trace the physical structure of the body down to the molecular level and still have no explanation for beliefs, desires, memory and creativity. In his book Quantum Healing, Chopra stated the conclusion that quantum entanglement links everything in the universe, and therefore it must create consciousness. Claims of quantum consciousness are, however, disputed by scientists arguing that quantum effects have no effect in systems on the macro-level systems (i.e., the brain).

Approach to health care

Chopra argues that everything that happens in the mind and brain is physically represented elsewhere in the body, with mental states (thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and memories) directly influencing physiology through neurotransmitters such as dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin. He has stated, "Your mind, your body and your consciousness – which is your spirit – and your social interactions, your personal relationships, your environment, how you deal with the environment, and your biology are all inextricably woven into a single process ... By influencing one, you influence everything."

Chopra and physicians at the Chopra Center practice integrative medicine, combining the medical model of conventional Western medicine with alternative therapies such as yoga, mindfulness meditation, and Ayurveda. According to Ayurveda, illness is caused by an imbalance in the patient's doshas or humors, and is treated with diet, exercise and meditative practices – based on the medical evidence there is, however, nothing in Ayurvedic medicine that is known to be effective at treating disease, and some preparations may be actively harmful, although meditation may be useful in promoting general wellbeing.

In discussing health care, Chopra has used the term "quantum healing", which he defined in Quantum Healing (1989) as the "ability of one mode of consciousness (the mind) to spontaneously correct the mistakes in another mode of consciousness (the body)". This attempted to wed the Maharishi's version of Ayurvedic medicine with concepts from physics, an example of what cultural historian Kenneth Zysk called "New Age Ayurveda". The book introduced Chopra's view that a person's thoughts and feelings give rise to all cellular processes.

Chopra coined the term quantum healing to invoke the idea of a process whereby a person's health "imbalance" is corrected by quantum mechanical means. Chopra said that quantum phenomena are responsible for health and wellbeing. He has attempted to integrate Ayurveda, a traditional Indian system of medicine, with quantum mechanics to justify his teachings. According to Robert Carroll, he "charges $25,000 per lecture performance, where he spouts a few platitudes and gives spiritual advice while warning against the ill effects of materialism".

Chopra has equated spontaneous remission in cancer to a change in a quantum state, corresponding to a jump to "a new level of consciousness that prohibits the existence of cancer". Physics professor Robert L. Park has written that physicists "wince" at the "New Age quackery" in Chopra's cancer theories, and characterizes them as a cruel fiction, since adopting them in place of effective treatment risks compounding the ill effects of the disease with guilt, and might rule out the prospect of getting a genuine cure.

Chopra's claims of quantum healing have attracted controversy due to what has been described as a "systematic misinterpretation" of modern physics. Chopra's connections between quantum mechanics and alternative medicine are widely regarded in the scientific community as being invalid. The main criticism revolves around the fact that macroscopic objects are too large to exhibit inherently quantum properties like interference and wave function collapse. Most literature on quantum healing is almost entirely theosophical, omitting the rigorous mathematics that makes quantum electrodynamics possible.

Physicists have objected to Chopra's use of terms from quantum physics. For example, he was awarded the satirical Ig Nobel Prize in physics in 1998 for "his unique interpretation of quantum physics as it applies to life, liberty, and the pursuit of economic happiness". When Chopra and Jean Houston debated Sam Harris and Michael Shermer in 2010 on the question "Does God Have a Future?", Harris argued that Chopra's use of "spooky physics" merged two language games in a "completely unprincipled way". Interviewed in 2007 by Richard Dawkins, Chopra said that he used the term quantum as a metaphor when discussing healing and that it had little to do with quantum theory in physics.

Chopra wrote in 2000 that his AIDS patients were combining mainstream medicine with activities based on Ayurveda, including taking herbs, meditation and yoga. He acknowledges that AIDS is caused by the HIV virus, but says that, "'[h]earing' the virus in its vicinity, the DNA mistakes it for a friendly or compatible sound". Ayurveda uses vibrations which are said to correct this supposed sound distortion. Medical professor Lawrence Schneiderman writes that Chopra's treatment has "to put it mildly...no supporting empirical data".

In 2001, ABC News aired a show segment on the topic of distance healing and prayer. In it, Chopra said that "there is a realm of reality that goes beyond the physical where in fact we can influence each other from a distance". Chopra was shown using his claimed mental powers in an attempt to relax a person in another room, whose vital signs were recorded in charts which were said to show a correspondence between Chopra's periods of concentration and the subject's periods of relaxation. After the show, a poll of its viewers found that 90% of them believed in distance healing. Health and science journalist Christopher Wanjek has criticized the experiment, saying that any correspondence evident from the charts would prove nothing, but that even so freezing the frame of the video showed the correspondences were not so close as claimed. Wanjek characterized the broadcast as "an instructive example of how bad medicine is presented as exciting news" which had "a dependence on unusual or sensational science results that others in the scientific community renounce as unsound".

Alternative medicine

Chopra has been described as "America's most prominent spokesman for Ayurveda". His treatments benefit from the placebo response. Chopra states "The placebo effect is real medicine, because it triggers the body's healing system." Physician and former U.S. Air Force flight surgeon Harriet Hall has criticized Chopra for his promotion of Ayurveda, stating that "it can be dangerous", referring to studies showing that 64% of Ayurvedic remedies sold in India are contaminated with significant amounts of heavy metals like mercury, arsenic, and cadmium and a 2015 study of users in the United States who found elevated blood lead levels in 40% of those tested."

Chopra has metaphorically described the AIDS virus as emitting "a sound that lures the DNA to its destruction". The condition can be treated, according to Chopra, with "Ayurveda's primordial sound". Taking issue with this view, medical professor Lawrence Schneiderman has said that ethical issues are raised when alternative medicine is not based on empirical evidence and that, "to put it mildly, Dr. Chopra proposes a treatment and prevention program for AIDS that has no supporting empirical data".

He is placed by David Gorski among the "quacks", "cranks" and "purveyors of woo", and described as "arrogantly obstinate". The New York Times in 2013 stated that Deepak Chopra is "the controversial New Age guru and booster of alternative medicine". Time magazine stated that he is "the poet-prophet of alternative medicine." He has become one of the best-known and wealthiest figures in the holistic-health movement. The New York Times argued that his publishers have used his medical degree on the covers of his books as a way to promote the books and buttress their claims. In 1999, Time magazine included Chopra in its list of the 20th century's heroes and icons. Cosmo Landesman wrote in 2005 that Chopra was "hardly a man now, more a lucrative new age brand – the David Beckham of personal/spiritual growth". For Timothy Caulfield, Chopra is an example of someone using scientific language to promote treatments that are not grounded in science: "[Chopra] legitimizes these ideas that have no scientific basis at all, and makes them sound scientific. He really is a fountain of meaningless jargon." A 2008 Time magazine article by Ptolemy Tompkins commented that Chopra was a "magnet for criticism" for most of his career, and most of it was from the medical and scientific professionals. Opinions ranged from the "dismissive" to the "outright damning". Chopra's claims for the effectiveness of alternative medicine can, some have argued, lure sick people away from medical treatment. Tompkins however considered Chopra a "beloved" individual whose basic messages centered on "love, health and happiness" had made him rich because of their popular appeal. English professor George O'Har argues that Chopra exemplifies the need of human beings for meaning and spirit in their lives, and places what he calls Chopra's "sophistries" alongside the emotivism of Oprah Winfrey. Paul Kurtz writes that Chopra's "regnant spirituality" is reinforced by postmodern criticism of the notion of objectivity in science, while Wendy Kaminer equates Chopra's views with irrational belief systems such as New Thought, Christian Science, and Scientology.

Aging

Chopra believes that "ageing is simply learned behaviour" that can be slowed or prevented. Chopra has said that he expects "to live way beyond 100". He states that "by consciously using our awareness, we can influence the way we age biologically...You can tell your body not to age." Conversely, Chopra also says that aging can be accelerated, for example by a person engaging in "cynical mistrust". Robert Todd Carroll has characterized Chopra's promotion of lengthened life as a selling of "hope" that seems to be "a false hope based on an unscientific imagination steeped in mysticism and cheerily dispensed gibberish".

Spirituality and religion

Chopra has likened the universe to a "reality sandwich" which has three layers: the "material" world, a "quantum" zone of matter and energy, and a "virtual" zone outside of time and space, which is the domain of God, and from which God can direct the other layers. Chopra has written that human beings' brains are "hardwired to know God" and that the functions of the human nervous system mirror divine experience. Chopra has written that his thinking has been inspired by Jiddu Krishnamurti, a 20th-century speaker and writer on philosophical and spiritual subjects.

In 2012, reviewing War of the Worldviews – a book co-authored by Chopra and Leonard Mlodinow – physics professor Mark Alford says that the work is set out as a debate between the two authors, "[covering] all the big questions: cosmology, life and evolution, the mind and brain, and God". Alford considers the two sides of the debate a false opposition and says that "the counterpoint to Chopra's speculations is not science, with its complicated structure of facts, theories, and hypotheses", but rather Occam's razor.

In August 2005, Chopra wrote a series of articles on the creation–evolution controversy and Intelligent design, which were criticized by science writer Michael Shermer, founder of The Skeptics Society. In 2010, Shermer said that Chopra is "the very definition of what we mean by pseudoscience".

Position on skepticism

Paul Kurtz, an American skeptic and secular humanist, has written that the popularity of Chopra's views is associated with increasing anti-scientific attitudes in society, and such popularity represents an assault on the objectivity of science itself by seeking new, alternative forms of validation for ideas. Kurtz says that medical claims must always be submitted to open-minded but proper scrutiny, and that skepticism "has its work cut out for it".

In 2013, Chopra published an article on what he saw as "skepticism" at work in Wikipedia, arguing that a "stubborn band of militant skeptics" were editing articles to prevent what he believes would be a fair representation of the views of such figures as Rupert Sheldrake, an author, lecturer, and researcher in parapsychology. The result, Chopra argued, was that the encyclopedia's readers were denied the opportunity to read of attempts to "expand science beyond its conventional boundaries". The biologist Jerry Coyne responded, saying that it was instead Chopra who was losing out as his views were being "exposed as a lot of scientifically-sounding psychobabble".

More broadly, Chopra has attacked skepticism as a whole, writing in The Huffington Post that "No skeptic, to my knowledge, ever made a major scientific discovery or advanced the welfare of others." Astronomer Phil Plait said this statement trembled "on the very edge of being a blatant and gross lie", listing Carl Sagan, Richard Feynman, Stephen Jay Gould, and Edward Jenner among the "thousands of scientists [who] are skeptics", who he said were counterexamples to Chopra's statement.

Misuse of scientific terminology

Reviewing Susan Jacoby's book, The Age of American Unreason, Wendy Kaminer sees Chopra's popular reception in the US as being symptomatic of many Americans' historical inability (as Jacoby puts it) "to distinguish between real scientists and those who peddled theories in the guise of science". Chopra's "nonsensical references to quantum physics" are placed in a lineage of American religious pseudoscience, extending back through Scientology to Christian Science. Physics professor Chad Orzel has written that "to a physicist, Chopra's babble about 'energy fields' and 'congealing quantum soup' presents as utter gibberish", but that Chopra makes enough references to technical terminology to convince non-scientists that he understands physics. English professor George O'Har writes that Chopra is an exemplification of the fact that human beings need "magic" in their lives, and places "the sophistries of Chopra" alongside the emotivism of Oprah Winfrey, the special effects and logic of Star Trek, and the magic of Harry Potter.

Chopra has been criticized for his frequent references to the relationship of quantum mechanics to healing processes, a connection that has drawn skepticism from physicists who say it can be considered as contributing to the general confusion in the popular press regarding quantum measurement, decoherence and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. In 1998, Chopra was awarded the satirical Ig Nobel Prize in physics for "his unique interpretation of quantum physics as it applies to life, liberty, and the pursuit of economic happiness". When interviewed by ethologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in the Channel 4 (UK) documentary The Enemies of Reason, Chopra said that he used the term "quantum physics" as "a metaphor" and that it had little to do with quantum theory in physics. In March 2010, Chopra and Jean Houston debated Sam Harris and Michael Shermer at the California Institute of Technology on the question "Does God Have a Future?" Shermer and Harris criticized Chopra's use of scientific terminology to expound unrelated spiritual concepts. A 2015 paper examining "the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit" used Chopra's Twitter feed as the canonical example, and compared this with fake Chopra quotes generated by a spoof website.

Yoga

In April 2010, Aseem Shukla, co-founder of the Hindu American Foundation, criticized Chopra for suggesting that yoga did not have its origins in Hinduism but in an older Indian spiritual tradition. Chopra later said that yoga was rooted in "consciousness alone" expounded by Vedic rishis long before historic Hinduism ever arose. He said that Shukla had a "fundamentalist agenda". Shukla responded by saying Chopra was an exponent of the art of "How to Deconstruct, Repackage and Sell Hindu Philosophy Without Calling it Hindu!", and he said Chopra's mentioning of fundamentalism was an attempt to divert the debate.

Legal actions

In May 1991, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published an article by Chopra and two others on Ayurvedic medicine and TM. JAMA subsequently published an erratum stating that the lead author, Hari M. Sharma, had undisclosed financial interests, followed by an article by JAMA associate editor Andrew A. Skolnick which was highly critical of Chopra and the other authors for failing to disclose their financial connections to the article subject. Several experts on meditation and traditional Indian medicine criticized JAMA for accepting the "shoddy science" of the original article. Chopra and two TM groups sued Skolnick and JAMA for defamation, asking for $194 million in damages, but the case was dismissed in March 1993.

After Chopra published his book, Ageless Body, Timeless Mind (1993), he was sued for copyright infringement by Robert Sapolsky for having used, without proper attribution, "five passages of text and one table" displaying information on the endocrinology of stress. An out-of-court settlement resulted in Chopra correctly attributing material that was researched by Sapolsky.

Select bibliography

According to publishers HarperCollins, Chopra has written more than 80 books which have been translated into more than 43 languages, including numerous New York Times bestsellers in both fiction and nonfiction categories. His book The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success was on The New York Times Best Seller list for 72 weeks.

Books

- Creating Health. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1987. ISBN 978-0-395-42953-2.

- Quantum Healing. New York: Bantam Books. 1989. ISBN 978-0-553-05368-5.

- Perfect Health. New York: Harmony Books. 1990. ISBN 0517571951.

- Return of the Rishi: A Doctor's Story of Spiritual Transformation and Ayurvedic Healing. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1991. ISBN 978-0-395-57420-1.

- Ageless Body Timeless Mind. New York: Harmony Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0-517-59257-1.

- The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success. San Rafael: Amber Allen Publishing and New World Library. 1994. ISBN 978-1-878424-11-2.

- The Return of Merlin. New York: Harmony Books. 1995. ISBN 978-0-517-59849-8.

- The Way of the Wizard. New York: Random House. 1995. ISBN 978-0-517-70434-9.

- The Path to Love. New York: Harmony Books. 1997. ISBN 978-0-517-70622-0.

- with Simon, David (2000). The Chopra Center Herbal Handbook. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-609-80390-5.

- The Book of Secrets. New York: Harmony. 2004. ISBN 978-0-517-70624-4.

- The Third Jesus. New York: Harmony Books. 2008. ISBN 978-0-307-33831-0.

- Reinventing the Body, Resurrecting the Soul. New York: Harmony Books. 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-45233-7.

- The Soul of Leadership. New York: Harmony Books. 2010. ISBN 978-0-307-40806-8.

- with Mlodinow, Leonard (2011). War of the Worldviews. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-88688-0.

- with Chopra, Gotham (May 31, 2011). The Seven Spiritual Laws of Superheroes: Harnessing Our Power to Change the World. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-205966-6.

- God: A Story of Revelation. New York: HarperOne. October 8, 2013. ISBN 978-0-06-202069-7.

- with Tanzi, Rudolph E. (2012). Super Brain. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-95682-8.

- with Chopra, Danjiv (2013). Brotherhood: Dharma, Destiny, and the American Dream. New York: New Harvest. ISBN 978-0-544-03210-1.

- What Are You Hungry For?. New York: Harmony Books. 2013. ISBN 978-0-7704-3721-3.

- with Tanzi, Rudolph E. (2015). Super Genes. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-8041-4013-3.

- with Kafatos, Menas (2017). You Are the Universe. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0307889164.

- Metahuman. New York: Harmony. 2019. ISBN 978-0307338334.

- Total Meditation. Harmony. 2020. ISBN 9781984825315.

- with Tanzi, Rudolph E. (2020). The Healing Self. Harmony. ISBN 9780451495549.

- with Platt-Finger, Sarah (2023). Living in the Light: Yoga for Self-Realization. Random House. ISBN 9780593235423.