From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proletarian_internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory that capitalism is a world-system and therefore the working classes of all nations must act in concert if they are to replace it with communism.

Proletarian internationalism was strongly embraced by the first communist party, the Communist League, as exercised through its slogan "Proletarians of all countries, unite!", later popularized as "Workers of the world, unite!" in English literature. This notion was also embraced by the Bolshevik Party. After the formation of the Soviet Union, Marxist proponents of internationalism suggested that country could be used as a "homeland of communism" from which revolution could be spread around the globe. Though world revolution continued to figure prominently in Soviet rhetoric for decades, it no longer superseded domestic concerns on the government's agenda, especially after the ascension of Joseph Stalin. Despite this, the Soviet Union continued to foster international ties with communist and left-wing parties and governments around the world. It played a fundamental role in the establishment of several socialist states in Eastern Europe after World War II and backed the creation of others in Asia, Latin America and Africa. The Soviets also funded dozens of insurgencies being waged against colonialist governments by leftist guerrilla movements worldwide. A few other states later exercised their own commitments to the cause of world revolution. Cuba frequently dispatched internationalist military missions abroad to defend communist interests in Africa and the Caribbean.

Proponents of proletarian internationalism often argued that the objectives of a given revolution should be global rather than local in scope—for example, triggering or perpetuating revolutions elsewhere. Proletarian internationalism is closely linked to goals of world revolution, to be achieved through successive or simultaneous communist revolutions in all nations. According to Marxist theory, successful proletarian internationalism should lead to world communism and eventually stateless communism.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Proletarian internationalism is summed up in the slogan coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, "Workers of the world, unite!", the last line of The Communist Manifesto, published in 1848. However, Marx and Engels' approach to the national question was also shaped by tactical considerations in their pursuit of a long-term revolutionary strategy. In 1848, the proletariat was a small minority in all but a handful of countries. Political and economic conditions needed to ripen in order to advance the possibility of proletarian revolution.

For instance, Marx and Engels supported the emergence of an independent and democratic Poland, which at the time was divided between Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary. Rosa Luxemburg's biographer Peter Nettl writes: "In general, Marx and Engels' conception of the national-geographical rearrangement of Europe was based on four criteria: the development of progress, the creation of large-scale economic units, the weighting of approval and disapproval in accordance with revolutionary possibilities, and their specific enmity to Russia". Russia was seen as the heartland of European reaction at the time.

First International

The trade unionists who formed the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), sometimes called the First International, recognised that the working class was an international class which had to link its struggle on an international scale. By joining together across national borders, the workers would gain greater bargaining power and political influence.

Founded in 1864, the IWA was the first mass movement with a specifically international focus. At its peak, the IWA had 5 million members according to police reports from the various countries in which it had a significant presence. Repression in Europe and internal divisions between the anarchist and Marxist currents led eventually to its dissolution in 1876. Shortly thereafter, the Marxist and revolutionary socialist tendencies continued the internationalist strategy of the IWA through the successor organisation of the Second International, though without the inclusion of the anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist movements.

Second International

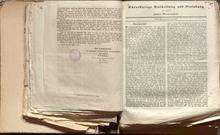

Proletarian internationalism was perhaps best expressed in the resolution sponsored by Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg at the Seventh Congress of the Second International at Stuttgart in 1907 which asserted:

Wars between capitalist states are, as a rule, the outcome of their competition on the world market, for each state seeks not only to secure its existing markets, but also to conquer new ones. In this, the subjugation of foreign peoples and countries plays a prominent role. These wars result furthermore from the incessant race for armaments by militarism, one of the chief instruments of bourgeois class rule and of the economic and political subjugation of the working class.

Wars are favored by the national prejudices which are systematically cultivated among civilized peoples in the interest of the ruling classes for the purpose of distracting the proletarian masses from their own class tasks as well as from their duties of international solidarity.

Wars, therefore, are part of the very nature of capitalism; they will cease only when the capitalist system is abolished or when the enormous sacrifices in men and money required by the advance in military technique and the indignation called forth by armaments, drive the peoples to abolish this system.

The resolution concluded:

If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working classes and their parliamentary representatives in the countries involved, supported by the coordinating activity of the International Socialist Bureau, to exert every effort in order to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the sharpening of the class struggle and the sharpening of the general political situation.

In case war should break out anyway, it is their duty to intervene in favor of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilize the economic and political crisis created by the war to rouse the masses and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.

However, Luxemburg and Lenin had very different interpretations of the national question. Lenin and the Bolsheviks opposed imperialism and chauvinism by advocating a policy of national self-determination, including the right of oppressed nations to secede from Russia. They believed this would help to create the conditions for unity between the workers in both oppressing and oppressed nations. Specifically, Lenin claimed: "The bourgeois nationalism of any oppressed nation has a general democratic content that is directed against oppression and it is this content that we unconditionally support".

By contrast, Luxemburg broke with the mainstream Polish Socialist Party in 1893 on the national question. She argued that the nature of Russia had changed since Marx's day as Russia was now fast developing as a major capitalist nation while the Polish bourgeoisie now had its interests linked to Russian capitalism. This had opened the possibility of a class alliance between the Polish and Russian working class.

The leading party of the Second International, the Social Democratic Party of Germany, voted overwhelmingly in support of Germany's entry into World War I by approving war credits on 4 August 1914. Many other member parties of the Second International followed suit by supporting national governments and the Second International was dissolved in 1916. Proletarian internationalists characterized the combination of social democracy and nationalism as social chauvinism.

World War I

The hopes of internationalists such as Lenin, Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were dashed by the initial enthusiasm for war. Lenin tried to re-establish socialist unity against the war at the Zimmerwald Conference, but the majority of delegates took a pacifist rather than a revolutionary position.

In prison, Luxemburg deepened her analysis with The Junius Pamphlet of 1915. In this document, she specifically rejects the notion of oppressor and oppressed states: "Imperialism is not the creation of one or any group of states. It is the product of a particular stage of ripeness in the world development of capital, an innately international condition, an indivisible whole, that is recognisable only in all its relations, and from which no nation can hold aloof at will".

Proletarian internationalists now argued that the alliances of World War I had proved that socialism and nationalism were incompatible in the imperialist era, that the concept of national self-determination had become outdated and in particular that nationalism would prove to be an obstacle to proletarian unity. Anarcho-syndicalism was another working class political current that characterised the war as imperialist on all sides, finding organisational expression in the Industrial Workers of the World.

The internationalist perspective influenced the revolutionary wave towards the end of World War I, notably with Russia's withdrawal from the conflict following the October Revolution and the revolt in Germany beginning in the naval ports of Kiel and Wilhelmshaven that brought the war to an end in November 1918. However, once this revolutionary wave had receded in the early 1920s, proletarian internationalism was no longer mainstream in working class politics.

Third International: Leninism versus left communism

Following World War I, the international socialist movement was irreconcilably split into two hostile factions: on the one side, the social democrats, who broadly supported their national governments during the conflict; and on the other side Leninists and their allies who formed the new communist parties that were organised into the Third International, which was established in March 1919. During the Russian Civil War, Lenin and Leon Trotsky more firmly embraced the concept of national self-determination for tactical reasons. In the Third International, the national question became a major bone of contention between mainstream Marxist-Leninists and "left communists".

By the time World War II broke out in 1939, only a few prominent communists such as the Italian Marxist Onorato Damen and the Dutch council communist Anton Pannekoek remained opponents of Russia's embrace of national self-determination, while the left communist Amadeo Bordiga remained in support of national determination for regions that had not yet moved past their pre-capitalist modes of production. Following the collapse of the Mussolini regime in Italy in 1943, communists in Italy clandestinely regrouped and founded the Internationalist Communist Party (PCInt). The first edition of the party organ, Prometeo (Prometheus), proclaimed: "Workers! Against the slogan of a national war which arms Italian workers against English and German proletarians, oppose the slogan of the communist revolution, which unites the workers of the world against their common enemy — capitalism". The PCInt took the view that Luxemburg, not Lenin, had been right on the national question, though the Bordigists would later split in opposition to this view among others in 1952.

Socialist internationalism and the postwar era

There was a revival of interest in internationalist theory after World War II, when the extent of communist influence in Eastern Europe dramatically increased as a result of postwar military occupations by the Soviet Union. The Soviet government defined its relationship with Eastern European states it occupied such as Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary as based on the principles of proletarian internationalism. The theory was used to justify installing "people's democracies" in these states, which were to oversee the transition from fascism to Communism. By the early 1960s, this thinking was considered obsolete as most of the "people's democracies" had established cohesive postwar communist states. Communist ideologues believed that proletarian internationalism was no longer accurate to describe Soviet relations with the newly emerging Eastern European communist bloc, so a new term was coined, namely socialist internationalism. According to Soviet internationalist theory under Nikita Khrushchev, proletarian internationalism could only be evoked to describe solidarity between international peoples and parties, not governments. Inter-state relationships fell into a parallel category, socialist internationalism.

Socialist internationalism was considerably less militant than proletarian internationalism as it was not focused on the spread of revolution, but diplomatic, political and to a lesser extent cultural solidarity between preexisting regimes. Under the principles of socialist internationalism, the Warsaw Pact governments were encouraged to pursue various forms of economic or military cooperation with each other and Moscow. At the Moscow International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties in June 1969, seventy-five communist parties from around the world formally defined and endorsed the theory of socialist internationalism. One of the key tenets of socialist internationalism as expressed during the conference was that the "defense of socialism is the international duty of communists", meaning communist governments should be obliged to assist each other militarily to defend their common interests against external aggression.

Khrushchev's successor, Leonid Brezhnev, was an even more outspoken proponent of both proletarian and socialist internationalism. In 1976, Brezhnev declared that proletarian internationalism was neither dead nor obsolete and reaffirmed the Soviet Union's commitment to its core concepts of "the solidarity of the working class, of communists of all countries in the struggle for common goals, the solidarity in the struggle of the peoples for national liberation and social progress, [and] voluntary cooperation of the fraternal parties with strict observance of the equality and independence of each". Under Brezhnev, the Soviet and Warsaw Pact governments frequently evoked proletarian internationalism to fund leftist trade unions and guerrilla insurgencies around the globe. Foreign military interventions could also be justified as "internationalist duty" to defend or support other communist states during wartime. With Soviet financial or military backing, a considerable number of new communist governments succeeded in assuming power during the late 1960s and 1970s. The United States and its allies perceived this as an example of Soviet expansionism and this aspect of Brezhnev's foreign policy negatively affected diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the West.

Internationalism in Cuba

Outside of the Warsaw Pact, Cuba embraced its own aggressive theory of proletarian internationalism, which was primarily exercised through support for leftist revolutionary movements. One of the fundamental aspects of Cuban foreign policy between 1962 and 1990 was the "rule of internationalism", which dictated that Cuba must first and foremost support the cause of international revolution through whatever means are available to her. At the founding of the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America in 1966, Cuban President Fidel Castro declared that "for Cuban revolutionaries, the battleground against imperialism encompasses the entire world...the enemy is one and the same, the same one who attacks our shores and our territory, the same one who attacks everyone else. And so we say and proclaim that the revolutionary movement in every corner of the world can count on Cuban combat fighters". By the mid 1980s, it was estimated that up to a quarter of Cuba's national military was deployed overseas, fighting with communist governments or factions in various civil conflicts. The Cuban military saw action against the United States while fighting on behalf of the Marxist New Jewel Movement in Grenada. It was also instrumental in installing a communist government in Angola and fighting several costly campaigns during that nation's civil war.

Proletarian internationalism today

Communist Party of the Philippines theorist and activist Jose Maria Sison writes that while every proletarian party and state must be guided by proletarian internationalism, “this does not mean that revolution can be imported or exported from one country to another. Rather, revolutionary struggles must first take a national form."

Some political groupings such as the International Communist Party, the International Communist Current and the Internationalist Communist Tendency (formerly the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party, which includes the PCInt) follow the Luxemburgist and Bordigist interpretations of proletarian internationalism as do some libertarian communists.

Leftist opposition to proletarian internationalism

In contrast, some socialists have pointed out that social realities such as local loyalties and cultural barriers militate against proletarian internationalism. For example, George Orwell believed that "in all countries the poor are more national than the rich". To this, Marxists might counter that while the rich may have historically had the awareness and education to recognize cross-national interest of class, the poor of those same nations likely have not had this advantage, making them more susceptible to what Marxists would describe as the false ideology of patriotism. Marxists assert that patriotism and nationalism serve precisely to obscure opposing class interests that would otherwise pose a threat to the ruling class order.

Marxists would also point out that in times of intense revolutionary struggle (the most evident being the revolutionary periods of 1848, 1917–1923 and 1968) internationalism within the proletariat can overtake petty nationalisms as intense class struggles break out in multiple nations at the same time and the workers of those nations discover that they have more in common with other workers than with their own bourgeoisie.

On the question of imperialism and national determination, proponents of Third-Worldism argue that workers in "oppressor" nations (such as the United States or Israel) must first support national liberation movements in "oppressed" nations (such as Afghanistan or Palestine) before there can be any basis for proletarian internationalism. For example, Tony Cliff, a leading figure of the British Socialist Workers Party, denied the possibility of solidarity between Palestinians and Israelis in the current Middle East situation, writing that "Israel is not a colony suppressed by imperialism, but a settler’s citadel, a launching pad of imperialism. It is a tragedy that some of the very people who had been persecuted and massacred in such bestial fashion should themselves be driven into a chauvinistic, militaristic fervour, and become the blind tool of imperialism in subjugating the Arab masses".

Trotskyists argue that there must be a permanent revolution in Third World countries in which a bourgeoisie revolution will inevitably lead to a worker's revolution with an international scope. This can be seen in the October Revolution before the movement was stopped by Stalin, a proponent of socialism in one country. Because of this threat, the bourgeoisie in Third World countries will willingly subjugate themselves to national and capitalist interests in order to prevent a proletarian uprising. In a 1936 interview with journalist Roy W. Howard, Stalin articulated his rejection of world revolution and stated that “We never had such plans and intentions” and that “The export of revolution is nonsense”.

Internationalists would respond that capitalism has proved itself incapable of resolving the competing claims of different nationalisms and that the working class (of all countries) is oppressed by capitalism, not by other workers. Moreover, the global nature of capitalism and international finance make "national liberation" an impossibility. For internationalists, all national liberation movements, whatever their "progressive" gloss, are therefore obstacles to the communist goal of world revolution.