History

The idea of using microbes to produce electricity was conceived in the early twentieth century. M. C. Potter initiated the subject in 1911. Potter managed to generate electricity from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but the work received little coverage. In 1931, Branet Cohen created microbial half fuel cells that, when connected in series, were capable of producing over 35 volts with only a current of 2 milliamps.

A study by DelDuca et al. used hydrogen produced by the fermentation of glucose by Clostridium butyricum

as the reactant at the anode of a hydrogen and air fuel cell. Though

the cell functioned, it was unreliable owing to the unstable nature of

hydrogen production by the micro-organisms. This issue was resolved by Suzuki et al. in 1976, who produced a successful MFC design a year later.

In the late 1970s little was understood about how microbial fuel

cells functioned. The idea was studied by Robin M. Allen and later by H.

Peter Bennetto. People saw the fuel cell as a possible method for the

generation of electricity for developing countries. Bennetto's work,

starting in the early 1980s, helped build an understanding of how fuel

cells operate and he was seen by many as the topic's foremost authority.

In May 2007, the University of Queensland, Australia completed a prototype MFC as a cooperative effort with Foster's Brewing. The prototype, a 10 L design, converted brewery wastewater

into carbon dioxide, clean water and electricity. The group had plans

to create a pilot-scale model for an upcoming international bio-energy

conference.

Definition

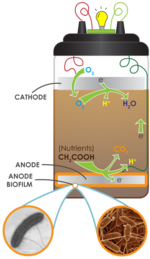

A microbial fuel cell (MFC) is a device that converts chemical energy to electrical energy by the action of microorganisms.

These electrochemical cells are constructed using either a bioanode

and/or a biocathode. Most MFCs contain a membrane to separate the

compartments of the anode (where oxidation takes place) and the cathode

(where reduction takes place). The electrons produced during oxidation

are transferred directly to an electrode or, to a redox

mediator species. The electron flux is moved to the cathode. The charge

balance of the system is compensated by ionic movement inside the cell,

usually across an ionic membrane. Most MFCs use an organic electron donor that is oxidized to produce CO2, protons and electrons. Other electron donors have been reported, such as sulfur compounds or hydrogen.

The cathode reaction uses a variety of electron acceptors that includes

the reduction of oxygen as the most studied process. However, other

electron acceptors have been studied, including metal recovery by

reduction, water to hydrogen, nitrate reduction and sulfate reduction.

Applications

Power generation

MFCs

are attractive for power generation applications that require only low

power, but where replacing batteries may be impractical, such as

wireless sensor networks.

Virtually any organic material could be used to feed the fuel cell, including coupling cells to wastewater treatment plants. Chemical process wastewater and synthetic wastewater have been used to produce bioelectricity in dual- and single-chamber mediatorless MFCs (uncoated graphite electrodes).

Higher power production was observed with a biofilm-covered graphite anode. Fuel cell emissions are well under regulatory limits. MFCs use energy more efficiently than standard internal combustion engines, which are limited by the Carnot Cycle. In theory, an MFC is capable of energy efficiency far beyond 50%. Rozendal obtained energy conversion to hydrogen 8 times that of conventional hydrogen production technologies.

However; MFCs can also work at a smaller scale. Electrodes in some cases need only be 7 μm thick by 2 cm long. such that an MFC can replace a battery. It provides a renewable form of energy and does not need to be recharged.

MFCs operate well in mild conditions, 20 °C to 40 °C and also at pH of around 7. They lack the stability required for long-term medical applications such as in pacemakers.

Power stations can be based on aquatic plants such as algae. If

sited adjacent to an existing power system, the MFC system can share its

electricity lines.

Education

Soil-based

microbial fuel cells serve as educational tools, as they encompass

multiple scientific disciplines (microbiology, geochemistry, electrical

engineering, etc.) and can be made using commonly available materials,

such as soils and items from the refrigerator. Kits for home science

projects and classrooms are available.

One example of microbial fuel cells being used in the classroom is in

the IBET (Integrated Biology, English, and Technology) curriculum for Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology. Several educational videos and articles are also available on the International Society for Microbial Electrochemistry and Technology (ISMET Society).

Biosensor

The current generated from a microbial fuel cell is directly

proportional to the energy content of wastewater used as the fuel. MFCs

can measure the solute concentration of wastewater (i.e., as a biosensor).

Wastewater is commonly assessed for its biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) values.

BOD values are determined by incubating samples for 5 days with proper

source of microbes, usually activated sludge collected from wastewater

plants.

An MFC-type BOD sensor can provide real-time BOD values. Oxygen

and nitrate are preferred electron acceptors over the electrode,

reducing current generation from an MFC. MFC BOD sensors underestimate

BOD values in the presence of these electron acceptors. This can be

avoided by inhibiting aerobic and nitrate respiration in the MFC using

terminal oxidase inhibitors such as cyanide and azide. Such BOD sensors are commercially available.

The United States Navy

is considering microbial fuel cells for environmental sensors. The use

of microbial fuel cells to power environmental sensors would be able to

provide power for longer periods and enable the collection and retrieval

of undersea data without a wired infrastructure. The energy created by

these fuel cells is enough to sustain the sensors after an initial

startup time.

Due to undersea conditions (high salt concentrations, fluctuating

temperatures and limited nutrient supply), the Navy may deploy MFCs with

a mixture of salt-tolerant microorganisms. A mixture would allow for a

more complete utilization of available nutrients. Shewanella oneidensis is their primary candidate, but may include other heat- and cold-tolerant Shewanella spp.

A first self-powered and autonomous BOD/COD biosensor has been

developed and allows to detect organic contaminants in freshwater. The

senor relies only on power produced by MFCs and operates continuously

without maintenance. The biosensor turns on the alarm to inform about

contamination level: the increased frequency of the signal informs about

higher contamination level, while low frequency warns about low

contamination level.

Biorecovery

In 2010, A. ter Heijne et al. constructed a device capable of producing electricity and reducing Cu (II) (ion) to copper metal.

Microbial electrolysis cells have been demonstrated to produce hydrogen.

Wastewater treatment

MFCs are used in water treatment to harvest energy utilizing anaerobic digestion.

The process can also reduce pathogens. However, it requires

temperatures upwards of 30 degrees C and requires an extra step in order

to convert biogas

to electricity. Spiral spacers may be used to increase electricity

generation by creating a helical flow in the MFC. Scaling MFCs is a

challenge because of the power output challenges of a larger surface

area.

Types

Mediated

Most microbial cells are electrochemically inactive. Electron transfer from microbial cells to the electrode is facilitated by mediators such as thionine, methyl viologen, methyl blue, humic acid and neutral red. Most available mediators are expensive and toxic.

Mediator-free

A plant microbial fuel cell (PMFC)

Mediator-free microbial fuel cells use electrochemically active

bacteria to transfer electrons to the electrode (electrons are carried

directly from the bacterial respiratory enzyme to the electrode). Among

the electrochemically active bacteria are Shewanella putrefaciens, Aeromonas hydrophila and others. Some bacteria are able to transfer their electron production via the pili on their external membrane. Mediator-free MFCs are less well characterized, such as the strain of bacteria used in the system, type of ion-exchange membrane and system conditions (temperature, pH, etc.)

Mediator-free microbial fuel cells can run on wastewater

and derive energy directly from certain plants. This configuration is

known as a plant microbial fuel cell. Possible plants include reed sweetgrass, cordgrass, rice, tomatoes, lupines and algae. Given that the power is derived from living plants (in situ-energy production), this variant can provide ecological advantages.

Microbial electrolysis

One variation of the mediator-less MFC is the microbial electrolysis

cell (MEC). While MFCs produce electric current by the bacterial

decomposition of organic compounds in water, MECs partially reverse the

process to generate hydrogen or methane by applying a voltage to

bacteria. This supplements the voltage generated by the microbial

decomposition of organics, leading to the electrolysis of water or methane production. A complete reversal of the MFC principle is found in microbial electrosynthesis, in which carbon dioxide is reduced by bacteria using an external electric current to form multi-carbon organic compounds.

Soil-based

A soil-based MFC

Soil-based microbial fuel cells adhere to the basic MFC principles, whereby soil acts as the nutrient-rich anodic media, the inoculum and the proton exchange membrane (PEM). The anode is placed at a particular depth within the soil, while the cathode rests on top the soil and is exposed to air.

Soils naturally teem with diverse microbes,

including electrogenic bacteria needed for MFCs, and are full of

complex sugars and other nutrients that have accumulated from plant and

animal material decay. Moreover, the aerobic

(oxygen consuming) microbes present in the soil act as an oxygen

filter, much like the expensive PEM materials used in laboratory MFC

systems, which cause the redox

potential of the soil to decrease with greater depth. Soil-based MFCs

are becoming popular educational tools for science classrooms.

Sediment microbial fuel cells (SMFCs) have been applied for wastewater treatment. Simple SMFCs can generate energy while decontaminating wastewater. Most such SMFCs contain plants to mimic constructed wetlands. By 2015 SMFC tests had reached more than 150 l.

In 2015 researchers announced an SMFC application that extracts energy and charges a battery.

Salts dissociate into positively and negatively charged ions in water

and move and adhere to the respective negative and positive electrodes,

charging the battery and making it possible to remove the salt effecting

microbial capacitive desalination. The microbes produce more energy than is required for the desalination process.

Phototrophic biofilm

Phototrophic biofilm MFCs (ner) use a phototrophic biofilm anode containing photosynthetic microorganism such as chlorophyta and candyanophyta. They carry out photosynthesis and thus produce organic metabolites and donate electrons.

One study found that PBMFCs display a power density sufficient for practical applications.

The sub-category of phototrophic MFCs that use purely oxygenic photosynthetic material at the anode are sometimes called biological photovoltaic systems.

Nanoporous membrane

The United States Naval Research Laboratory developed nanoporous membrane microbial fuel cells that use a non-PEM to generate passive diffusion within the cell. The membrane is a nonporous polymer filter (nylon, cellulose, or polycarbonate). It offers comparable power densities to Nafion

(a well known PEM) with greater durability. Porous membranes allow

passive diffusion thereby reducing the necessary power supplied to the

MFC in order to keep the PEM active and increasing the total energy

output.

MFCs that do not use a membrane can deploy anaerobic bacteria in

aerobic environments. However, membrane-less MFCs experience cathode

contamination by the indigenous bacteria and the power-supplying

microbe. The novel passive diffusion of nanoporous membranes can achieve

the benefits of a membrane-less MFC without worry of cathode

contamination.

Nanoporous membranes are also eleven times cheaper than Nafion (Nafion-117, $0.22/cm2 vs. polycarbonate, <$0.02/cm2).

Ceramic membrane

PEM membranes can be replaced with ceramic materials. Ceramic membrane costs can be as low as $5.66 /m2. The macroporous structure of ceramic membranes allows good transport of ionic species.

The materials that have been successfully employed in ceramic MFCs are earthenware, alumina, mullite, pyrophyllite and terracotta.

Generation process

When microorganisms consume a substance such as sugar in aerobic conditions, they produce carbon dioxide and water. However, when oxygen is not present, they produce carbon dioxide, protons/hydrogen ions and electrons, as described below:

-

C12H22O11 + 13H2O → 12CO2 + 48H+ + 48e−(Eq. 1)

Microbial fuel cells use inorganic mediators to tap into the electron transport chain of cells and channel electrons produced. The mediator crosses the outer cell lipid membranes and bacterial outer membrane;

then, it begins to liberate electrons from the electron transport chain

that normally would be taken up by oxygen or other intermediates.

The now-reduced mediator exits the cell laden with electrons that

it transfers to an electrode; this electrode becomes the anode. The

release of the electrons recycles the mediator to its original oxidised

state, ready to repeat the process. This can happen only under anaerobic conditions; if oxygen is present, it will collect the electrons, as it has greater electronegativity.

In MFC operation, the anode is the terminal electron acceptor

recognized by bacteria in the anodic chamber. Therefore, the microbial

activity is strongly dependent on the anode's redox potential. A Michaelis-Menten curve was obtained between the anodic potential and the power output of an acetate-driven MFC. A critical anodic potential seems to provide maximum power output.

Potential mediators include natural red, methylene blue, thionine and resorufin.

Organisms capable of producing an electric current are termed exoelectrogens. In order to turn this current into usable electricity, exoelectrogens have to be accommodated in a fuel cell.

The mediator and a micro-organism such as yeast, are mixed together in a solution to which is added a substrate such as glucose. This mixture is placed in a sealed chamber to stop oxygen entering, thus forcing the micro-organism to undertake anaerobic respiration. An electrode is placed in the solution to act as the anode.

In the second chamber of the MFC is another solution and the

positively charged cathode. It is the equivalent of the oxygen sink at

the end of the electron transport chain, external to the biological

cell. The solution is an oxidizing agent

that picks up the electrons at the cathode. As with the electron chain

in the yeast cell, this could be a variety of molecules such as oxygen,

although a more convenient option is a solid oxidizing agent, which

requires less volume.

Connecting the two electrodes is a wire (or other electrically

conductive path). Completing the circuit and connecting the two chambers

is a salt bridge or ion-exchange membrane. This last feature allows the

protons produced, as described in Eq. 1, to pass from the anode chamber to the cathode chamber.

The reduced mediator carries electrons from the cell to the

electrode. Here the mediator is oxidized as it deposits the electrons.

These then flow across the wire to the second electrode, which acts as

an electron sink. From here they pass to an oxidizing material. Also the

hydrogen ions/protons are moved from the anode to the cathode via a

proton exchange membrane such as nafion.

They will move across to the lower concentration gradient and be

combined with the oxygen but to do this they need an electron. This

forms current and the hydrogen is used sustaining the concentration

gradient.

Algae Biomass has been observed to give high energy when used as substrates in microbial fuel cell.