A crop-duster spraying pesticide on a field

A Lite-Trac four-wheeled self-propelled crop sprayer spraying pesticide on a field

Pesticides are substances that are meant to control pests, including weeds. The term pesticide includes all of the following: herbicide, insecticides (which may include insect growth regulators, termiticides, etc.) nematicide, molluscicide, piscicide, avicide, rodenticide, bactericide, insect repellent, animal repellent, antimicrobial, and fungicide. The most common of these are herbicides which account for approximately 80% of all pesticide use.

Most pesticides are intended to serve as plant protection products

(also known as crop protection products), which in general, protect

plants from weeds, fungi, or insects.

In general, a pesticide is a chemical or biological agent (such as a virus, bacterium, or fungus) that deters, incapacitates, kills, or otherwise discourages pests. Target pests can include insects, plant pathogens, weeds, molluscs, birds, mammals, fish, nematodes (roundworms), and microbes that destroy property, cause nuisance, or spread disease, or are disease vectors. Along with these benefits, pesticides also have drawbacks, such as potential toxicity to humans and other species.

Definition

| Type of pesticide | Target pest group |

|---|---|

| Algicides or algaecides | Algae |

| Avicides | Birds |

| Bactericides | Bacteria |

| Fungicides | Fungi and oomycetes |

| Herbicides | Plant |

| Insecticides | Insects |

| Miticides or acaricides | Mites |

| Molluscicides | Snails |

| Nematicides | Nematodes |

| Rodenticides | Rodents |

| Virucides | Viruses |

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has defined pesticide as

- any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, or controlling any pest, including vectors of human or animal disease, unwanted species of plants or animals, causing harm during or otherwise interfering with the production, processing, storage, transport, or marketing of food, agricultural commodities, wood and wood products or animal feedstuffs, or substances that may be administered to animals for the control of insects, arachnids, or other pests in or on their bodies. The term includes substances intended for use as a plant growth regulator, defoliant, desiccant, or agent for thinning fruit or preventing the premature fall of fruit. Also used as substances applied to crops either before or after harvest to protect the commodity from deterioration during storage and transport.

Pesticides can be classified by target organism (e.g., herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, rodenticides, and pediculicides – see table), chemical structure (e.g., organic, inorganic, synthetic, or biological (biopesticide), although the distinction can sometimes blur), and physical state (e.g. gaseous (fumigant)). Biopesticides include microbial pesticides and biochemical pesticides. Plant-derived pesticides, or "botanicals", have been developing quickly. These include the pyrethroids, rotenoids, nicotinoids, and a fourth group that includes strychnine and scilliroside.

Many pesticides can be grouped into chemical families. Prominent insecticide families include organochlorines, organophosphates, and carbamates. Organochlorine hydrocarbons (e.g., DDT)

could be separated into dichlorodiphenylethanes, cyclodiene compounds,

and other related compounds. They operate by disrupting the

sodium/potassium balance of the nerve fiber, forcing the nerve to

transmit continuously. Their toxicities vary greatly, but they have been

phased out because of their persistence and potential to bioaccumulate. Organophosphate and carbamates largely replaced organochlorines. Both operate through inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, allowing acetylcholine

to transfer nerve impulses indefinitely and causing a variety of

symptoms such as weakness or paralysis. Organophosphates are quite toxic

to vertebrates and have in some cases been replaced by less toxic

carbamates.

Thiocarbamate and dithiocarbamates are subclasses of carbamates.

Prominent families of herbicides include phenoxy and benzoic acid

herbicides (e.g. 2,4-D), triazines (e.g., atrazine), ureas (e.g., diuron), and Chloroacetanilides (e.g., alachlor).

Phenoxy compounds tend to selectively kill broad-leaf weeds rather than

grasses. The phenoxy and benzoic acid herbicides function similar to

plant growth hormones, and grow cells without normal cell division,

crushing the plant's nutrient transport system. Triazines interfere with photosynthesis. Many commonly used pesticides are not included in these families, including glyphosate.

The application of pest control agents is usually carried out by dispersing the chemical in a (often hydrocarbon-based) solvent-surfactant

system to give a homogeneous preparation. A virus lethality study

performed in 1977 demonstrated that a particular pesticide did not

increase the lethality of the virus, however combinations which included

some surfactants and the solvent clearly showed that pretreatment with

them markedly increased the viral lethality in the test mice.

Pesticides can be classified based upon their biological mechanism function or application method. Most pesticides work by poisoning pests.

A systemic pesticide moves inside a plant following absorption by the

plant. With insecticides and most fungicides, this movement is usually

upward (through the xylem) and outward. Increased efficiency may be a result. Systemic insecticides, which poison pollen and nectar in the flowers, may kill bees and other needed pollinators.

In 2010, the development of a new class of fungicides called paldoxins was announced. These work by taking advantage of natural defense chemicals released by plants called phytoalexins,

which fungi then detoxify using enzymes. The paldoxins inhibit the

fungi's detoxification enzymes. They are believed to be safer and

greener.

History

Since before 2000 BC, humans have utilized pesticides to protect their crops. The first known pesticide was elemental sulfur dusting used in ancient Sumer about 4,500 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia. The Rig Veda, which is about 4,000 years old, mentions the use of poisonous plants for pest control. By the 15th century, toxic chemicals such as arsenic, mercury, and lead were being applied to crops to kill pests. In the 17th century, nicotine sulfate was extracted from tobacco leaves for use as an insecticide. The 19th century saw the introduction of two more natural pesticides, pyrethrum, which is derived from chrysanthemums, and rotenone, which is derived from the roots of tropical vegetables. Until the 1950s, arsenic-based pesticides were dominant. Paul Müller discovered that DDT

was a very effective insecticide. Organochlorines such as DDT were

dominant, but they were replaced in the U.S. by organophosphates and

carbamates by 1975. Since then, pyrethrin compounds have become the dominant insecticide.

Herbicides became common in the 1960s, led by "triazine and other

nitrogen-based compounds, carboxylic acids such as

2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, and glyphosate".

The first legislation providing federal authority for regulating pesticides was enacted in 1910;

however, decades later during the 1940s manufacturers began to produce

large amounts of synthetic pesticides and their use became widespread. Some sources consider the 1940s and 1950s to have been the start of the "pesticide era." Although the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1970 and amendments to the pesticide law in 1972, pesticide use has increased 50-fold since 1950 and 2.3 million tonnes (2.5 million short tons) of industrial pesticides are now used each year.

Seventy-five percent of all pesticides in the world are used in

developed countries, but use in developing countries is increasing.

A study of USA pesticide use trends through 1997 was published in 2003

by the National Science Foundation's Center for Integrated Pest

Management.

In the 1960s, it was discovered that DDT was preventing many fish-eating birds from reproducing, which was a serious threat to biodiversity. Rachel Carson wrote the best-selling book Silent Spring about biological magnification. The agricultural use of DDT is now banned under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, but it is still used in some developing nations to prevent malaria and other tropical diseases by spraying on interior walls to kill or repel mosquitoes.

Uses

Pesticides are used to control organisms that are considered to be harmful. For example, they are used to kill mosquitoes that can transmit potentially deadly diseases like West Nile virus, yellow fever, and malaria. They can also kill bees, wasps or ants that can cause allergic reactions. Insecticides can protect animals from illnesses that can be caused by parasites such as fleas. Pesticides can prevent sickness in humans that could be caused by moldy food or diseased produce. Herbicides can be used to clear roadside weeds, trees, and brush. They can also kill invasive weeds that may cause environmental damage. Herbicides are commonly applied in ponds and lakes to control algae

and plants such as water grasses that can interfere with activities

like swimming and fishing and cause the water to look or smell

unpleasant. Uncontrolled pests such as termites and mold can damage structures such as houses. Pesticides are used in grocery stores and food storage facilities to manage rodents

and insects that infest food such as grain. Each use of a pesticide

carries some associated risk. Proper pesticide use decreases these

associated risks to a level deemed acceptable by pesticide regulatory

agencies such as the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) of Canada.

DDT, sprayed on the walls of houses, is an organochlorine that has been used to fight malaria since the 1950s. Recent policy statements by the World Health Organization have given stronger support to this approach.

However, DDT and other organochlorine pesticides have been banned in

most countries worldwide because of their persistence in the environment

and human toxicity. DDT use is not always effective, as resistance to DDT was identified in Africa as early as 1955, and by 1972 nineteen species of mosquito worldwide were resistant to DDT.

Amount used

In 2006 and 2007, the world used approximately 2.4 megatonnes (5.3×109 lb)

of pesticides, with herbicides constituting the biggest part of the

world pesticide use at 40%, followed by insecticides (17%) and

fungicides (10%). In 2006 and 2007 the U.S. used approximately 0.5

megatonnes (1.1×109 lb)

of pesticides, accounting for 22% of the world total, including

857 million pounds (389 kt) of conventional pesticides, which are used

in the agricultural sector (80% of conventional pesticide use) as well

as the industrial, commercial, governmental and home & garden

sectors. The state of California alone used 117 million pounds.

Pesticides are also found in majority of U.S. households with 88 million

out of the 121.1 million households indicating that they use some form

of pesticide in 2012. As of 2007, there were more than 1,055 active ingredients registered as pesticides, which yield over 20,000 pesticide products that are marketed in the United States.

The US used some 1 kg (2.2 pounds) per hectare of arable land compared with: 4.7 kg in China, 1.3 kg in the UK, 0.1 kg in Cameroon,

5.9 kg in Japan and 2.5 kg in Italy. Insecticide use in the US has

declined by more than half since 1980 (.6%/yr), mostly due to the near

phase-out of organophosphates. In corn fields, the decline was even steeper, due to the switchover to transgenic Bt corn.

For the global market of crop protection products, market analysts forecast revenues of over 52 billion US$ in 2019.

Benefits

Pesticides

can save farmers' money by preventing crop losses to insects and other

pests; in the U.S., farmers get an estimated fourfold return on money

they spend on pesticides. One study found that not using pesticides reduced crop yields by about 10%.

Another study, conducted in 1999, found that a ban on pesticides in the

United States may result in a rise of food prices, loss of jobs, and an

increase in world hunger.

There are two levels of benefits for pesticide use, primary and

secondary. Primary benefits are direct gains from the use of pesticides

and secondary benefits are effects that are more long-term.

Primary benefits

Controlling pests and plant disease vectors:

- Improved crop yields

- Improved crop/livestock quality

- Invasive species controlled

Controlling human/livestock disease vectors and nuisance organisms:

- Human lives saved and disease reduced. Diseases controlled include malaria, with millions of lives having been saved or enhanced with the use of DDT alone.

- Animal lives saved and disease reduced

Controlling organisms that harm other human activities and structures:

- Drivers view unobstructed

- Tree/brush/leaf hazards prevented

- Wooden structures protected

Monetary

In

one study, it was estimated that for every dollar ($1) that is spent on

pesticides for crops can yield up to four dollars ($4) in crops saved.

This means based that, on the amount of money spent per year on

pesticides, $10 billion, there is an additional $40 billion savings in

crop that would be lost due to damage by insects and weeds. In general,

farmers benefit from having an increase in crop yield and from being

able to grow a variety of crops throughout the year. Consumers of

agricultural products also benefit from being able to afford the vast

quantities of produce available year-round.

Costs

On the cost side of pesticide use there can be costs to the environment, costs to human health, as well as costs of the development and research of new pesticides.

Health effects

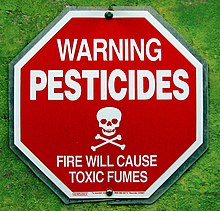

A sign warning about potential pesticide exposure

Pesticides may cause acute and delayed health effects in people who are exposed.

Pesticide exposure can cause a variety of adverse health effects,

ranging from simple irritation of the skin and eyes to more severe

effects such as affecting the nervous system, mimicking hormones causing

reproductive problems, and also causing cancer. A 2007 systematic review found that "most studies on non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukemia showed positive associations with pesticide exposure" and thus concluded that cosmetic use of pesticides should be decreased. There is substantial evidence of associations between organophosphate insecticide exposures and neurobehavioral alterations. Limited evidence also exists for other negative outcomes from pesticide exposure including neurological, birth defects, and fetal death.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limiting exposure of children to pesticides and using safer alternatives.

Owing to inadequate regulation and safety precautions, 99% of

pesticide related deaths occur in developing countries that account for

only 25% of pesticide usage.

One study found pesticide self-poisoning the method of choice in

one third of suicides worldwide, and recommended, among other things,

more restrictions on the types of pesticides that are most harmful to

humans.

A 2014 epidemiological review found associations between autism

and exposure to certain pesticides, but noted that the available

evidence was insufficient to conclude that the relationship was causal.

Large quantities of presumably nontoxic petroleum oil by-products are introduced into the environment as pesticide dispersal agents and emulsifiers. A 1976 study found that an increase in viral lethality with a concomitant influence on the liver and central nervous system occurs in young mice previously primed with such chemicals.

The World Health Organization and the UN Environment Programme estimate that each year, 3 million workers in agriculture in the developing world experience severe poisoning from pesticides, about 18,000 of whom die. According to one study, as many as 25 million workers in developing countries may suffer mild pesticide poisoning yearly.

There are several careers aside from agriculture that may also put

individuals at risk of health effects from pesticide exposure including

pet groomers, groundskeepers, and fumigators.

Pesticide use is widespread in Latin America, as around US $3

billion are spend each year in the region. It has been recorded that

pesticide poisonings have been increasing each year for the past two

decades. It was estimated that 50–80% of the cases are unreported. It is

indicated by studies that organophosphate and carbamate insecticides

are the most frequent source of pesticide poisoning.

Environmental effects

Pesticide use raises a number of environmental concerns. Over 98% of

sprayed insecticides and 95% of herbicides reach a destination other

than their target species, including non-target species, air, water and

soil. Pesticide drift

occurs when pesticides suspended in the air as particles are carried by

wind to other areas, potentially contaminating them. Pesticides are one

of the causes of water pollution, and some pesticides are persistent organic pollutants and contribute to soil and flower (pollen, nectar) contamination.

In addition, pesticide use reduces biodiversity, contributes to pollinator decline, destroys habitat (especially for birds), and threatens endangered species.

Pests can develop a resistance to the pesticide (pesticide resistance), necessitating a new pesticide. Alternatively a greater dose of the pesticide can be used to counteract the resistance, although this will cause a worsening of the ambient pollution problem.

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, listed 9 of the 12 most dangerous and persistent organic chemicals that were (now mostly obsolete) organochlorine pesticides. Since chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides dissolve in fats and are not excreted, organisms tend to retain them almost indefinitely. Biological magnification

is the process whereby these chlorinated hydrocarbons (pesticides) are

more concentrated at each level of the food chain. Among marine animals,

pesticide concentrations are higher in carnivorous fishes, and even

more so in the fish-eating birds and mammals at the top of the ecological pyramid. Global distillation

is the process whereby pesticides are transported from warmer to colder

regions of the Earth, in particular the Poles and mountain tops.

Pesticides that evaporate into the atmosphere at relatively high

temperature can be carried considerable distances (thousands of

kilometers) by the wind to an area of lower temperature, where they

condense and are carried back to the ground in rain or snow.

In order to reduce negative impacts, it is desirable that

pesticides be degradable or at least quickly deactivated in the

environment. Such loss of activity or toxicity of pesticides is due to

both innate chemical properties of the compounds and environmental

processes or conditions. For example, the presence of halogens within a chemical structure often slows down degradation in an aerobic environment. Adsorption to soil may retard pesticide movement, but also may reduce bioavailability to microbial degraders.

Economics

| Harm | Annual US cost |

|---|---|

| Public health | $1.1 billion |

| Pesticide resistance in pest | $1.5 billion |

| Crop losses caused by pesticides | $1.4 billion |

| Bird losses due to pesticides | $2.2 billion |

| Groundwater contamination | $2.0 billion |

| Other costs | $1.4 billion |

| Total costs | $9.6 billion |

In one study, the human health and environmental costs due to pesticides in the United States was estimated to be $9.6 billion: offset by about $40 billion in increased agricultural production.

Additional costs include the registration process and the cost of

purchasing pesticides: which are typically borne by agrichemical

companies and farmers respectively. The registration process can take

several years to complete (there are 70 different types of field test)

and can cost $50–70 million for a single pesticide. At the beginning of the 21st century, the United States spent approximately $10 billion on pesticides annually.

Alternatives

Alternatives to pesticides are available and include methods of cultivation, use of biological pest controls (such as pheromones and microbial pesticides), genetic engineering, and methods of interfering with insect breeding. Application of composted yard waste has also been used as a way of controlling pests.

These methods are becoming increasingly popular and often are safer

than traditional chemical pesticides. In addition, EPA is registering

reduced-risk conventional pesticides in increasing numbers.

Cultivation practices include polyculture (growing multiple types of plants), crop rotation,

planting crops in areas where the pests that damage them do not live,

timing planting according to when pests will be least problematic, and

use of trap crops that attract pests away from the real crop. Trap crops have successfully controlled pests in some commercial agricultural systems while reducing pesticide usage;

however, in many other systems, trap crops can fail to reduce pest

densities at a commercial scale, even when the trap crop works in

controlled experiments.

In the U.S., farmers have had success controlling insects by spraying

with hot water at a cost that is about the same as pesticide spraying.

Release of other organisms that fight the pest is another example

of an alternative to pesticide use. These organisms can include natural

predators or parasites of the pests. Biological pesticides based on entomopathogenic fungi, bacteria and viruses cause disease in the pest species can also be used.

Interfering with insects' reproduction can be accomplished by sterilizing males of the target species and releasing them, so that they mate with females but do not produce offspring. This technique was first used on the screwworm fly in 1958 and has since been used with the medfly, the tsetse fly, and the gypsy moth. However, this can be a costly, time consuming approach that only works on some types of insects.

Push pull strategy

The term "push-pull" was established in 1987 as an approach for integrated pest management

(IPM). This strategy uses a mixture of behavior-modifying stimuli to

manipulate the distribution and abundance of insects. "Push" means the

insects are repelled or deterred away from whatever resource that is

being protected. "Pull" means that certain stimuli (semiochemical

stimuli, pheromones, food additives, visual stimuli, genetically altered

plants, etc.) are used to attract pests to trap crops where they will

be killed. There are numerous different components involved in order to implement a Push-Pull Strategy in IPM.

Many case studies testing the effectiveness of the push-pull

approach have been done across the world. The most successful push-pull

strategy was developed in Africa for subsistence farming. Another

successful case study was performed on the control of Helicoverpa

in cotton crops in Australia. In Europe, the Middle East, and the

United States, push-pull strategies were successfully used in the

controlling of Sitona lineatus in bean fields.

Some advantages of using the push-pull method are less use of

chemical or biological materials and better protection against insect

habituation to this control method. Some disadvantages of the push-pull

strategy is that if there is a lack of appropriate knowledge of

behavioral and chemical ecology of the host-pest interactions then this

method becomes unreliable. Furthermore, because the push-pull method is

not a very popular method of IPM operational and registration costs are

higher.

Effectiveness

Some evidence shows that alternatives to pesticides can be equally effective as the use of chemicals. For example, Sweden has halved its use of pesticides with hardly any reduction in crops. In Indonesia, farmers have reduced pesticide use on rice fields by 65% and experienced a 15% crop increase. A study of Maize fields in northern Florida found that the application of composted yard waste with high carbon to nitrogen ratio to agricultural fields was highly effective at reducing the population of plant-parasitic nematodes

and increasing crop yield, with yield increases ranging from 10% to

212%; the observed effects were long-term, often not appearing until the

third season of the study.

However, pesticide resistance is increasing. In the 1940s, U.S.

farmers lost only 7% of their crops to pests. Since the 1980s, loss has

increased to 13%, even though more pesticides are being used. Between 500 and 1,000 insect and weed species have developed pesticide resistance since 1945.

Types

Pesticides

are often referred to according to the type of pest they control.

Pesticides can also be considered as either biodegradable pesticides,

which will be broken down by microbes and other living beings into

harmless compounds, or persistent pesticides, which may take months or

years before they are broken down: it was the persistence of DDT, for

example, which led to its accumulation in the food chain and its killing

of birds of prey at the top of the food chain. Another way to think

about pesticides is to consider those that are chemical pesticides are

derived from a common source or production method.

Insecticides

Neonicotinoids are a class of neuro-active insecticides chemically similar to nicotine. Imidacloprid, of the neonicotanoid family, is the most widely used insecticide in the world.

In the late 1990s neonicotinoids came under increasing scrutiny over

their environmental impact and were linked in a range of studies to

adverse ecological effects, including honey-bee colony collapse disorder (CCD) and loss of birds due to a reduction in insect populations. In 2013, the European Union and a few non EU countries restricted the use of certain neonicotinoids.

Organophosphate and carbamate insecticides have a similar mode of action. They affect the nervous system of target pests (and non-target organisms) by disrupting acetylcholinesterase activity, the enzyme that regulates acetylcholine, at nerve synapses. This inhibition causes an increase in synaptic acetylcholine and over-stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Many of these insecticides, first developed in the mid 20th century,

are very poisonous. Although commonly used in the past, many older

chemicals have been removed from the market due to their health and

environmental effects (e.g. DDT, chlordane, and toxaphene). However, many organophosphates are not persistent in the environment.

Pyrethroid

insecticides were developed as a synthetic version of the naturally

occurring pesticide pyrethrin, which is found in chrysanthemums. They

have been modified to increase their stability in the environment. Some

synthetic pyrethroids are toxic to the nervous system.

Herbicides

A number of sulfonylureas have been commercialized for weed control, including: amidosulfuron, flazasulfuron, metsulfuron-methyl, rimsulfuron, sulfometuron-methyl, terbacil, nicosulfuron, and triflusulfuron-methyl. These are broad-spectrum herbicides that kill plants weeds or pests by inhibiting the enzyme acetolactate synthase.

In the 1960s, more than 1 kg/ha (0.89 lb/acre) crop protection chemical

was typically applied, while sulfonylureates allow as little as 1% as

much material to achieve the same effect.

Biopesticides

Biopesticides

are certain types of pesticides derived from such natural materials as

animals, plants, bacteria, and certain minerals. For example, canola oil

and baking soda have pesticidal applications and are considered

biopesticides. Biopesticides fall into three major classes:

- Microbial pesticides which consist of bacteria, entomopathogenic fungi or viruses (and sometimes includes the metabolites that bacteria or fungi produce). Entomopathogenic nematodes are also often classed as microbial pesticides, even though they are multi-cellular.

- Biochemical pesticides or herbal pesticides are naturally occurring substances that control (or monitor in the case of pheromones) pests and microbial diseases.

- Plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs) have genetic material from other species incorporated into their genetic material (i.e. GM crops). Their use is controversial, especially in many European countries.

Classified by type of pest

Pesticides that are related to the type of pests are:

| Type | Action |

|---|---|

| Algicides | Control algae in lakes, canals, swimming pools, water tanks, and other sites |

| Antifouling agents | Kill or repel organisms that attach to underwater surfaces, such as boat bottoms |

| Antimicrobials | Kill microorganisms (such as bacteria and viruses) |

| Attractants | Attract pests (for example, to lure an insect or rodent to a trap). (However, food is not considered a pesticide when used as an attractant.) |

| Biopesticides | Biopesticides are certain types of pesticides derived from such natural materials as animals, plants, bacteria, and certain minerals |

| Biocides | Kill microorganisms |

| Disinfectants and sanitizers | Kill or inactivate disease-producing microorganisms on inanimate objects |

| Fungicides | Kill fungi (including blights, mildews, molds, and rusts) |

| Fumigants | Produce gas or vapor intended to destroy pests in buildings or soil |

| Herbicides | Kill weeds and other plants that grow where they are not wanted |

| Insecticides | Kill insects and other arthropods |

| Miticides | Kill mites that feed on plants and animals |

| Microbial pesticides | Microorganisms that kill, inhibit, or out compete pests, including insects or other microorganisms |

| Molluscicides | Kill snails and slugs |

| Nematicides | Kill nematodes (microscopic, worm-like organisms that feed on plant roots) |

| Ovicides | Kill eggs of insects and mites |

| Pheromones | Biochemicals used to disrupt the mating behavior of insects |

| Repellents | Repel pests, including insects (such as mosquitoes) and birds |

| Rodenticides | Control mice and other rodents |

Further types

The term pesticide also include these substances:

Desiccants: Promote drying of living tissues, such as unwanted plant tops.

Insect growth regulators: Disrupt the molting, maturity from pupal stage to adult, or other life processes of insects.

Plant growth regulators: Substances (excluding fertilizers or other plant nutrients) that alter the expected growth, flowering, or reproduction rate of plants.

Wood preservatives: They are used to make wood resistant to insects, fungus, and other pests.

Regulation

International

In many countries, pesticides must be approved for sale and use by a government agency.

In Europe, EU legislation has been approved banning the use of highly toxic pesticides including those that are carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction, those that are endocrine-disrupting, and those that are persistent, bioaccumulative

and toxic (PBT) or very persistent and very bioaccumulative (vPvB) and

measures have been approved to improve the general safety of pesticides

across all EU member states.

Though pesticide regulations differ from country to country,

pesticides, and products on which they were used are traded across

international borders. To deal with inconsistencies in regulations among

countries, delegates to a conference of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization

adopted an International Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of

Pesticides in 1985 to create voluntary standards of pesticide

regulation for different countries. The Code was updated in 1998 and 2002.

The FAO claims that the code has raised awareness about pesticide

hazards and decreased the number of countries without restrictions on

pesticide use.

Three other efforts to improve regulation of international pesticide trade are the United Nations London Guidelines for the Exchange of Information on Chemicals in International Trade and the United Nations Codex Alimentarius Commission.

The former seeks to implement procedures for ensuring that prior

informed consent exists between countries buying and selling pesticides,

while the latter seeks to create uniform standards for maximum levels

of pesticide residues among participating countries.

Pesticides safety education and pesticide applicator regulation are designed to protect the public from pesticide misuse,

but do not eliminate all misuse. Reducing the use of pesticides and

choosing less toxic pesticides may reduce risks placed on society and

the environment from pesticide use. Integrated pest management, the use of multiple approaches to control pests, is becoming widespread and has been used with success in countries such as Indonesia, China, Bangladesh, the U.S., Australia, and Mexico. IPM attempts to recognize the more widespread impacts of an action on an ecosystem, so that natural balances are not upset.

New pesticides are being developed, including biological and botanical

derivatives and alternatives that are thought to reduce health and

environmental risks. In addition, applicators are being encouraged to

consider alternative controls and adopt methods that reduce the use of

chemical pesticides.

Pesticides can be created that are targeted to a specific pest's lifecycle, which can be environmentally more friendly. For example, potato cyst nematodes

emerge from their protective cysts in response to a chemical excreted

by potatoes; they feed on the potatoes and damage the crop. A similar chemical can be applied to fields early, before the potatoes are planted, causing the nematodes to emerge early and starve in the absence of potatoes.

United States

Preparation for an application of hazardous herbicide in the US

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for regulating pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA).

Studies must be conducted to establish the conditions in which

the material is safe to use and the effectiveness against the intended

pest(s).

The EPA regulates pesticides to ensure that these products do not pose

adverse effects to humans or the environment, with an emphasis on the

health and safety of children.

Pesticides produced before November 1984 continue to be reassessed in

order to meet the current scientific and regulatory standards. All

registered pesticides are reviewed every 15 years to ensure they meet

the proper standards.

During the registration process, a label is created. The label contains

directions for proper use of the material in addition to safety

restrictions. Based on acute toxicity, pesticides are assigned to a Toxicity Class.

Pesticides are the most thoroughly tested chemicals after drugs in the

United States; those used on food requires more than 100 tests to

determine a range of potential impacts.

Some pesticides are considered too hazardous for sale to the general public and are designated restricted use pesticides. Only certified applicators, who have passed an exam, may purchase or supervise the application of restricted use pesticides.

Records of sales and use are required to be maintained and may be

audited by government agencies charged with the enforcement of pesticide

regulations. These records must be made available to employees and state or territorial environmental regulatory agencies.

In addition to the EPA, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) set standards for the level of pesticide residue that is allowed on or in crops. The EPA looks at what the potential human health and environmental effects might be associated with the use of the pesticide.

In addition, the U.S. EPA uses the National Research Council's

four-step process for human health risk assessment: (1) Hazard

Identification, (2) Dose-Response Assessment, (3) Exposure Assessment,

and (4) Risk Characterization.

Recently Kaua'i County (Hawai'i) passed Bill No. 2491 to add an

article to Chapter 22 of the county's code relating to pesticides and

GMOs. The bill strengthens protections of local communities in Kaua'i

where many large pesticide companies test their products.

Residue

Pesticide residue refers to the pesticides that may remain on or in food after they are applied to food crops.

The maximum allowable levels of these residues in foods are often

stipulated by regulatory bodies in many countries. Regulations such as

pre-harvest intervals also often prevent harvest of crop or livestock

products if recently treated in order to allow residue concentrations to

decrease over time to safe levels before harvest. Exposure of the

general population to these residues most commonly occurs through

consumption of treated food sources, or being in close contact to areas

treated with pesticides such as farms or lawns.

Many of these chemical residues, especially derivatives of chlorinated pesticides, exhibit bioaccumulation which could build up to harmful levels in the body as well as in the environment. Persistent chemicals can be magnified through the food chain

and have been detected in products ranging from meat, poultry, and

fish, to vegetable oils, nuts, and various fruits and vegetables.

Pesticide contamination in the environment can be monitored through bioindicators such as bee pollinators.