The Fat Man mushroom cloud resulting from the nuclear explosion over Nagasaki rises into the air from the hypocenter.

The debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki concerns the ethical, legal, and military controversies surrounding the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 August and 9 August 1945 at the close of World War II (1939–45). The Soviet Union declared war on Japan an hour before 9 August and invaded Manchuria at one minute past midnight; Japan surrendered on 15 August.

On 26 July 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, United Kingdom Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Chairman of the Chinese Nationalist Government Chiang Kai-shek issued the Potsdam Declaration, which outlined the terms of surrender for the Empire of Japan as agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference. This ultimatum stated if Japan did not surrender, it would face "prompt and utter destruction".

Some debaters focus on the presidential decision-making process, and

others on whether or not the bombings were the proximate cause of

Japanese surrender.

Over the course of time, different arguments have gained and lost

support as new evidence has become available and as new studies have

been completed. A primary and continuing focus has been on the role of

the bombings in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s justification for them

based upon the premise that the bombings precipitated the surrender.

This remains the subject of both scholarly

and popular debate. In 2005, in an overview of historiography about the

matter, J. Samuel Walker wrote, "the controversy over the use of the

bomb seems certain to continue".

Walker stated, "The fundamental issue that has divided scholars over a

period of nearly four decades is whether the use of the bomb was

necessary to achieve victory in the war in the Pacific on terms

satisfactory to the United States."

Supporters of the bombings generally assert that they caused the

Japanese surrender, preventing massive casualties on both sides in the planned invasion of Japan: Kyūshū was to be invaded in November 1945 and Honshū

four months later. It was thought Japan would not surrender unless

there was an overwhelming demonstration of destructive capability. Those

who oppose the bombings argue it was militarily unnecessary, inherently immoral, a war crime, or a form of state terrorism. Critics believe a naval blockade and conventional bombings would have forced Japan to surrender unconditionally.

Some critics believe Japan was more motivated to surrender by the

Soviet Union's invasion of Manchuria and other Japanese-held areas.

Support

It would prevent many U.S. military casualties

There are voices which assert that the bomb should never have been used at all. I cannot associate myself with such ideas. ... I am surprised that very worthy people—but people who in most cases had no intention of proceeding to the Japanese front themselves—should adopt the position that rather than throw this bomb, we should have sacrificed a million American and a quarter of a million British lives.

— Winston Churchill, leader of the Opposition, in a speech to the British House of Commons, August 1945

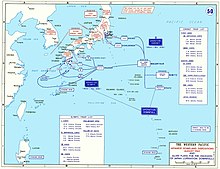

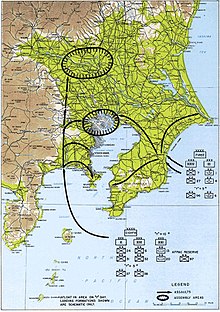

A map outlining the Japanese and U.S. (but not other Allied) ground forces scheduled to take part in the ground battle for Japan. Two landings were planned:

(1) Olympic – the invasion of the southern island, Kyūshū,

(2) Coronet – the invasion of the main island, Honshū.

(1) Olympic – the invasion of the southern island, Kyūshū,

(2) Coronet – the invasion of the main island, Honshū.

March 1946's Operation Coronet was planned to take Tokyo with a landing of 25 divisions, compared to D-Day's 12 divisions.

Those who argue in favor of the decision to drop the atomic bombs on enemy targets believe massive casualties on both sides would have occurred in Operation Downfall, the planned Allied invasion of Japan.

The bulk of the force invading Japan would be American although the

British Commonwealth would contribute three divisions of troops (one

each from the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia).

The U.S. anticipated losing many combatants in Downfall, although the number of expected fatalities and wounded is subject to some debate. U.S. President Harry S. Truman stated in 1953 he had been advised U.S. casualties could range from 250,000 to one million combatants. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Ralph Bard, a member of the Interim Committee

on atomic matters, stated that while meeting with Truman in the summer

of 1945 they discussed the bomb's use in the context of massive

combatant and non-combatant casualties from invasion, with Bard raising

the possibility of a million Allied combatants being killed. As Bard

opposed using the bomb without warning Japan first, he cannot be accused

of exaggerating casualty expectations to justify the bomb's use, and

his account is evidence that Truman was aware of, and government

officials discussed, the possibility of one million casualties.

A quarter of a million casualties is roughly the level the Joint

War Plans Committee estimated, in its paper (JWPC 369/1) prepared for

Truman's 18 June meeting. A review of documents from the Truman Library

shows Truman's initial draft response to the query describes Marshall

only as saying "one quarter of a million would be the minimum". The "as

much as a million" phrase was added to the final draft by Truman's

staff, so as not to appear to contradict an earlier statement given in a

published article by Stimson (former Secretary of War).

In a study done by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in April 1945, the figures

of 7.45 casualties per 1,000 man-days and 1.78 fatalities per 1,000

man-days were developed. This implied the two planned campaigns to

conquer Japan would cost 1.6 million U.S. casualties, including 380,000

dead. JWPC 369/1 (prepared June 15, 1945) which provided planning information to the Joint Chiefs of Staff,

estimated an invasion of Japan would result in 40,000 U.S. dead and

150,000 wounded. Delivered on June 15, 1945, after insight gained from the Battle of Okinawa,

the study noted Japan's inadequate defenses resulting from a very

effective sea blockade and the Allied firebombing campaign. Generals George C. Marshall and Douglas MacArthur signed documents agreeing with the Joint War Plans Committee estimate.

In addition, a large number of Japanese combatant and

non-combatant casualties were expected as a result of such actions.

Contemporary estimates of Japanese deaths from an invasion of the Home

Islands range from several hundreds of thousands to as high as ten

million. General MacArthur's staff provided an estimated range of

American deaths depending on the duration of the invasion, and also

estimated a 22:1 ratio of Japanese to American deaths. From this, a low

figure of somewhat more than 200,000 Japanese deaths can be calculated

for a short invasion of two weeks, and almost three million Japanese

deaths if the fighting lasted four months. A widely cited estimate of five to ten million Japanese deaths came from a study by William Shockley and Quincy Wright; the upper figure was used by Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, who characterized it as conservative. Some 400,000 additional Japanese deaths might have occurred in the expected Soviet invasion of Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan's main islands, although the Soviets lacked the naval capability to invade the Japanese home islands, let alone to take Hokkaido. An Air Force Association

webpage states that "Millions of women, old men, and boys and girls had

been trained to resist by such means as attacking with bamboo spears

and strapping explosives to their bodies and throwing themselves under advancing tanks."

The AFA noted that "[t]he Japanese cabinet had approved a measure

extending the draft to include men from ages fifteen to sixty and women

from seventeen to forty-five (an additional 28 million people)".

The great loss of life during the battle of Iwo Jima and other Pacific islands

gave U.S. leaders an idea of the casualties that would happen with a

mainland invasion. Of the 22,060 Japanese combatants entrenched on Iwo

Jima, 21,844 died either from fighting or by ritual suicide. Only 216

Japanese POWs were held at the hand of the Americans during the battle.

According to the official Navy Department Library website, "The 36-day

(Iwo Jima) assault resulted in more than 26,000 American casualties,

including 6,800 dead" with 19,217 wounded. To put this into context, the 82-day Battle of Okinawa

lasted from early April until mid-June 1945 and U.S. casualties (out of

five Army and two Marine divisions) were above 62,000, of which more

than 12,000 were killed or missing.

The U.S. military had nearly 500,000 Purple Heart

medals manufactured in anticipation of potential casualties from the

planned invasion of Japan. To date, all American military casualties of

the 60 years following the end of World War II, including the Korean and Vietnam Wars, have not exceeded that number. In 2003, there were still 120,000 of these Purple Heart medals in stock.

Because of the number available, combat units in Iraq and Afghanistan

were able to keep Purple Hearts on hand for immediate award to wounded

soldiers on the field.

Speedy end of war saved lives

Supporters

of the bombings argue waiting for the Japanese to surrender would also

have cost lives. "For China alone, depending upon what number one

chooses for overall Chinese casualties, in each of the ninety-seven

months between July 1937 and August 1945, somewhere between 100,000 and

200,000 persons perished, the vast majority of them noncombatants. For

the other Asian states alone, the average probably ranged in the tens of

thousands per month, but the actual numbers were almost certainly

greater in 1945, notably due to the mass death in a famine in Vietnam.

Historian Robert P. Newman concluded that each month that the war

continued in 1945 would have produced the deaths of 'upwards of 250,000

people, mostly Asian but some Westerners.'"

The end of the war limited the expansion of the Japanese controlled Vietnamese famine of 1945, stopping it at 1–2 million deaths and also liberated millions of Allied prisoners of war and civilian laborers working in harsh conditions under a forced mobilization. In the Dutch East Indies, there was a "forced mobilization of some 4 million—although some estimates are as high as 10 million—romusha

(manual labourers) ... About 270,000 romusha were sent to the Outer

Islands and Japanese-held territories in Southeast Asia, where they

joined other Asians in performing wartime construction projects. At the

end of the war, only 52,000 were repatriated to Java."

Supporters also point to an order given by the Japanese War

Ministry on August 1, 1944, ordering the execution of Allied POWs, "when

an uprising of large numbers cannot be suppressed without the use of

firearms" or when the POW camp was in the combat zone, in fear that

"escapees from the camp may turn into a hostile fighting force".

The Operation Meetinghouse

firebombing raid on Tokyo alone killed 100,000 civilians on the night

of March 9–10, 1945, causing more civilian death and destruction than

the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A total of 350,000 civilians died in the incendiary raids on 67 Japanese cities. Because the United States Army Air Forces wanted to use its fission bombs on previously undamaged cities in order to have accurate data on nuclear-caused damage, Kokura, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Niigata were preserved from conventional bombing raids. Otherwise, they would all have been firebombed.

Intensive conventional bombing would have continued or increased prior

to an invasion. The submarine blockade and the United States Army Air

Forces's mining operation, Operation Starvation,

had effectively cut off Japan's imports. A complementary operation

against Japan's railways was about to begin, isolating the cities of

southern Honshū from the food grown elsewhere in the Home Islands.

"Immediately after the defeat, some estimated that 10 million people

were likely to starve to death", noted historian Daikichi Irokawa. Meanwhile, fighting continued in the Philippines, New Guinea and Borneo, and offensives were scheduled for September in southern China and Malaya. The Soviet invasion of Manchuria had, in the week before the surrender, caused over 80,000 deaths.

In September 1945, nuclear physicist Karl Taylor Compton,

who himself took part in the Manhattan Project, visited MacArthur's

headquarters in Tokyo, and following his visit wrote a defensive

article, in which he summarized his conclusions as follows:

If the atomic bomb had not been used, evidence like that I have cited points to the practical certainty that there would have been many more months of death and destruction on an enormous scale.

Philippine justice Delfin Jaranilla, member of the Tokyo tribunal, wrote in his judgment:

If a means is justified by an end, the use of the atomic bomb was justified for it brought Japan to her knees and ended the horrible war. If the war had gone longer, without the use of the atomic bomb, how many thousands and thousands of helpless men, women and children would have needlessly died and suffered ...?

Lee Kuan Yew, the Former Prime Minister of Singapore concurred:

But they also showed a meanness and viciousness towards their enemies equal to the Huns'. Genghis Khan and his hordes could not have been more merciless. I have no doubts about whether the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary. Without them, hundreds of thousands of civilians in Malaya and Singapore, and millions in Japan itself, would have perished.

Lee witnessed his home city being invaded by the Japanese and was nearly executed in the Sook Ching Massacre.

Part of total war

This Tokyo residential section was virtually destroyed following the Operation Meetinghouse fire-bombing of Tokyo on the night of 9/10 March 1945, which was the single deadliest air raid in human history;

with a greater loss of life than the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima or

Nagasaki as single events or a greater civilian death toll and area of

fire damage than both nuclear bombings combined.

Supporters of the bombings have argued the Japanese government had promulgated a National Mobilization Law and waged total war, ordering many civilians (including women, children, and old people) to work in factories and other infrastructure attached to the war effort

and to fight against any invading force. Unlike the United States and

Nazi Germany, over 90% of the Japanese war production was done in

unmarked workshops and cottage industries

which were widely dispersed within residential areas in cities and thus

making them more extensively difficult to find and attack. In addition,

the dropping of high explosives with precision bombing

was unable to penetrate Japan's dispersed industry, making it entirely

impossible to destroy them without causing widespread damage to

surrounding areas. General Curtis LeMay stated why he ordered the systematic carpet bombing of Japanese cities:

We were going after military targets. No point in slaughtering civilians for the mere sake of slaughter. Of course there is a pretty thin veneer in Japan, but the veneer was there. It was their system of dispersal of industry. All you had to do was visit one of those targets after we'd roasted it, and see the ruins of a multitude of houses, with a drill press sticking up through the wreckage of every home. The entire population got into the act and worked to make those airplanes or munitions of war ... men, women, children. We knew we were going to kill a lot of women and kids when we burned [a] town. Had to be done.

For six months prior to the use of nuclear weapons in combat, the United States Army Air Forces under LeMay's command undertook a major strategic bombing campaign against Japanese cities through the use of incendiary bombs, destroying 67 cities and killing an estimated 350,000 civilians. The Operation Meetinghouse

raid on Tokyo on the night of 9/10 March 1945 stands as the deadliest

air raid in human history, killing 100,000 civilians and destroying 16

square miles (41 km2) of the city that night, which caused

more civilian deaths and damage to urbanized land than any other single

air attack, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

combined.

Colonel Harry F. Cunningham, an intelligence officer of the Fifth Air Force, noted that in addition to civilians producing weapons of war in cities, the Japanese government created a large civilian militia organization

in order to train millions of civilians to be armed and to resist the

American invaders. In his official intelligence review on July 21, 1945,

he declared that:

The entire population of Japan is a proper military target ... There are no civilians in Japan. We are making war and making it in the all-out fashion which saves American lives, shortens the agony which war is and seeks to bring about an enduring peace. We intend to seek out and destroy the enemy wherever he or she is, in the greatest possible numbers, in the shortest possible time.

Supporters of the bombings have emphasized the strategic significance of the targets. Hiroshima was used as headquarters of the Second General Army and Fifth Division,

which commanded the defense of southern Japan with 40,000 combatants

stationed in the city. The city was also a communication center, an

assembly area for combatants, a storage point, and had major industrial

factories and workshops as well, and its air defenses consisted of five

batteries of 7-cm and 8-cm (2.8 and 3.1 inch) anti-aircraft guns.

Nagasaki was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging

industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, warships,

military equipment, and other war material. The city's air defenses

consisted of four batteries of 7 cm (2.8 in) anti-aircraft guns and two searchlight batteries.

An estimated 110,000 people were killed in the atomic bombings,

including 20,000 Japanese combatants and 20,000 Korean slave laborers in

Hiroshima and 23,145–28,113 Japanese factory workers, 2,000 Korean

slave laborers, and 150 Japanese combatants in Nagasaki.

On 30 June 2007, Japan's defense minister Fumio Kyūma

said the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan by the United States during

World War II was an inevitable way to end the war. Kyūma said: "I now

have come to accept in my mind that in order to end the war, it could

not be helped (shikata ga nai)

that an atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki and that countless numbers

of people suffered great tragedy." Kyūma, who is from Nagasaki, said the

bombing caused great suffering in the city, but he does not resent the

U.S. because it prevented the Soviet Union from entering the war with

Japan. Kyūma's comments were similar to those made by Emperor Hirohito

when, in his first ever press conference given in Tokyo in 1975, he was

asked what he thought of the bombing of Hiroshima, and answered: "It's

very regrettable that nuclear bombs were dropped and I feel sorry for

the citizens of Hiroshima but it couldn't be helped (shikata ga nai)

because that happened in wartime."

In early July 1945, on his way to Potsdam, Truman had re-examined

the decision to use the bomb. In the end, he made the decision to drop

the atomic bombs on strategic cities. His stated intention in ordering

the bombings was to save American lives, to bring about a quick

resolution of the war by inflicting destruction, and instilling fear of

further destruction, sufficient to cause Japan to surrender.

In his speech to the Japanese people presenting his reasons for

surrender on August 15, the Emperor referred specifically to the atomic

bombs, stating if they continued to fight it would not only result in

"an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also

it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization".

Commenting on the use of the atomic bomb, then-U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson stated, "The atomic bomb was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon."

In 1959, Mitsuo Fuchida, the pilot who led the first wave in the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, met with General Paul Tibbets, who piloted the Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and told him that:

You did the right thing. You know the Japanese attitude at that time, how fanatic they were, they'd die for the Emperor ... Every man, woman, and child would have resisted that invasion with sticks and stones if necessary ... Can you imagine what a slaughter it would be to invade Japan? It would have been terrible. The Japanese people know more about that than the American public will ever know.

Japan's leaders refused to surrender

Some

historians see ancient Japanese warrior traditions as a major factor in

the resistance in the Japanese military to the idea of surrender.

According to one Air Force account,

The Japanese code of Bushido—the way of the warrior'—was deeply ingrained. The concept of Yamato-damashii equipped each soldier with a strict code: never be captured, never break down, and never surrender. Surrender was dishonorable. Each soldier was trained to fight to the death and was expected to die before suffering dishonor. Defeated Japanese leaders preferred to take their own lives in the painful samurai ritual of seppuku (called hara kiri in the West). Warriors who surrendered were deemed not worthy of regard or respect.

Japanese militarism was aggravated by the Great Depression, and had resulted in countless assassinations of reformers attempting to check military power, among them Takahashi Korekiyo, Saitō Makoto, and Inukai Tsuyoshi. This created an environment in which opposition to war was a much riskier endeavor.

According to historian Richard B. Frank,

The intercepts of Japanese Imperial Army and Navy messages disclosed without exception that Japan's armed forces were determined to fight a final Armageddon battle in the homeland against an Allied invasion. The Japanese called this strategy Ketsu Go (Operation Decisive). It was founded on the premise that American morale was brittle and could be shattered by heavy losses in the initial invasion. American politicians would then gladly negotiate an end to the war far more generous than unconditional surrender.

The United States Department of Energy's history of the Manhattan Project lends some credence to these claims, saying that military leaders in Japan

also hoped that if they could hold out until the ground invasion of Japan began, they would be able to inflict so many casualties on the Allies that Japan still might win some sort of negotiated settlement.

While some members of the civilian leadership did use covert

diplomatic channels to attempt peace negotiation, they could not

negotiate surrender or even a cease-fire. Japan could legally enter into

a peace agreement only with the unanimous support of the Japanese

cabinet, and in the summer of 1945, the Japanese Supreme War Council,

consisting of representatives of the Army, the Navy, and the civilian

government, could not reach a consensus on how to proceed.

A political stalemate developed between the military and civilian

leaders of Japan, the military increasingly determined to fight despite

all costs and odds and the civilian leadership seeking a way to

negotiate an end to the war. Further complicating the decision was the

fact no cabinet could exist without the representative of the Imperial Japanese Army.

This meant the Army or Navy could veto any decision by having its

Minister resign, thus making them the most powerful posts on the SWC. In

early August 1945, the cabinet was equally split between those who

advocated an end to the war on one condition, the preservation of the kokutai, and those who insisted on three other conditions:

- Leave disarmament and demobilization to Imperial General Headquarters

- No occupation of the Japanese Home Islands, Korea, or Formosa

- Delegation to the Japanese government of the punishment of war criminals

The "hawks" consisted of General Korechika Anami, General Yoshijirō Umezu, and Admiral Soemu Toyoda and were led by Anami. The "doves" consisted of Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki, Naval Minister Mitsumasa Yonai, and Minister of Foreign Affairs Shigenori Tōgō and were led by Togo. Under special permission of Hirohito, the president of the Privy council, Hiranuma Kiichirō, was also a member of the imperial conference. For him, the preservation of the kokutai implied not only the Imperial institution but also the Emperor's reign.

Japan had an example of unconditional surrender in the German Instrument of Surrender. On 26 July, Truman and other Allied leaders—except the Soviet Union—issued the Potsdam Declaration

outlining terms of surrender for Japan. The declaration stated, "The

alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction." It was not accepted, though there is debate on Japan's intentions. The Emperor, who was waiting for a Soviet reply to Japanese peace feelers, made no move to change the government position. In the PBS documentary "Victory in the Pacific" (2005), broadcast in the American Experience series, historian Donald Miller argues, in the days after the declaration, the Emperor seemed more concerned with moving the Imperial Regalia of Japan to a secure location than with "the destruction of his country". This comment is based on declarations made by the Emperor to Kōichi Kido on 25 and 31 July 1945, when he ordered the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan to protect "at all cost" the Imperial Regalia.

It has sometimes been argued Japan would have surrendered if

simply guaranteed the Emperor would be allowed to continue as formal

head of state. However, Japanese diplomatic messages regarding a

possible Soviet mediation—intercepted through Magic,

and made available to Allied leaders—have been interpreted by some

historians to mean, "the dominant militarists insisted on preservation

of the old militaristic order in Japan, the one in which they ruled." On 18 and 20 July 1945, Ambassador Sato cabled to Foreign Minister Togo,

strongly advocating that Japan accept an unconditional surrender

provided that the U.S. preserved the imperial house (keeping the

emperor). On 21 July, in response, Togo rejected the advice, saying that

Japan would not accept an unconditional surrender under any

circumstance. Togo then said that, "Although it is apparent that there

will be more casualties on both sides in case the war is prolonged, we

will stand as united against the enemy if the enemy forcibly demands our

unconditional surrender." They also faced potential death sentences in trials for Japanese war crimes if they surrendered. This was also what occurred in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and other tribunals.

History professor Robert James Maddox wrote:

Another myth that has attained wide attention is that at least several of Truman's top military advisers later informed him that using atomic bombs against Japan would be militarily unnecessary or immoral, or both. There is no persuasive evidence that any of them did so. None of the Joint Chiefs ever made such a claim, although one inventive author has tried to make it appear that Leahy did by braiding together several unrelated passages from the admiral's memoirs. Actually, two days after Hiroshima, Truman told aides that Leahy had 'said up to the last that it wouldn't go off.'

Neither MacArthur nor Nimitz ever communicated to Truman any change of mind about the need for invasion or expressed reservations about using the bombs. When first informed about their imminent use only days before Hiroshima, MacArthur responded with a lecture on the future of atomic warfare and even after Hiroshima strongly recommended that the invasion go forward. Nimitz, from whose jurisdiction the atomic strikes would be launched, was notified in early 1945. 'This sounds fine,' he told the courier, 'but this is only February. Can't we get one sooner?'

The best that can be said about Eisenhower's memory is that it had become flawed by the passage of time.

Notes made by one of Stimson's aides indicate that there was a discussion of atomic bombs, but there is no mention of any protest on Eisenhower's part.

Maddox also wrote, "Even after both bombs had fallen and Russia

entered the war, Japanese militants insisted on such lenient peace terms

that moderates knew there was no sense even transmitting them to the

United States. Hirohito had to intervene personally on two occasions

during the next few days to induce hardliners to abandon their

conditions." "That they would have conceded defeat months earlier, before such calamities struck, is far-fetched to say the least."

Even after the triple shock of the Soviet intervention and two

atomic bombs, the Japanese cabinet was still deadlocked, incapable of

deciding upon a course of action due to the power of the Army and Navy

factions in cabinet, and of their unwillingness to even consider

surrender. Following the personal intervention of the emperor to break

the deadlock in favour of surrender, there were no less than three

separate coup attempts by senior Japanese officers to try to prevent the

surrender and take the Emperor into 'protective custody'. Once these

coup attempts had failed, senior leaders of the air force and Navy

ordered bombing and kamikaze

raids on the U.S. fleet (in which some Japanese generals personally

participated) to try to derail any possibility of peace. It is clear

from these accounts that while many in the civilian government knew the

war could not be won, the power of the military in the Japanese

government kept surrender from even being considered as a real option

prior to the two atomic bombs.

Another argument is that it was the Soviet declaration of war in

the days between the bombings that caused the surrender. After the war,

Admiral Soemu Toyoda

said, "I believe the Russian participation in the war against Japan

rather than the atom bombs did more to hasten the surrender." Prime Minister Suzuki also declared that the entry of the USSR into the war made "the continuance of the war impossible".

Upon hearing news of the event from Foreign Minister Togo, Suzuki

immediately said, "Let us end the war", and agreed to finally convene an

emergency meeting of the Supreme Council with that aim. The official

British history, The War Against Japan, also writes the Soviet

declaration of war "brought home to all members of the Supreme Council

the realization that the last hope of a negotiated peace had gone and

there was no alternative but to accept the Allied terms sooner or

later".

The "one condition" faction, led by Togo, seized on the bombing as decisive justification of surrender. Kōichi Kido,

one of Emperor Hirohito's closest advisers, stated, "We of the peace

party were assisted by the atomic bomb in our endeavor to end the war." Hisatsune Sakomizu, the chief Cabinet secretary in 1945, called the bombing "a golden opportunity given by heaven for Japan to end the war".

Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should We continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.

- Extract from Emperor Hirohito's Gyokuon-hōsō surrender speech, August 15, 1945

Japanese nuclear weapon program

During the war, and 1945 in particular, due to state secrecy, very

little was known outside Japan about the slow progress of the Japanese nuclear weapon program. The US knew that Japan had requested materials from their German allies, and 560 kg (1,230 lb) of unprocessed uranium oxide was dispatched to Japan in April 1945 aboard the submarine U-234,

which however surrendered to US forces in the Atlantic following

Germany's surrender. The uranium oxide was reportedly labeled as

"U-235", which may have been a mislabeling of the submarine's name; its

exact characteristics remain unknown. Some sources believe that it was

not weapons-grade material and was intended for use as a catalyst in the

production of synthetic methanol to be used for aviation fuel.

If post-war analysis had found that Japanese nuclear weapons

development was near completion, this discovery might have served in a revisionist

sense to justify the atomic attack on Japan. However, it is known that

the poorly coordinated Japanese project was considerably behind the US

developments in 1945, and also behind the unsuccessful German nuclear energy project of WWII.

A review in 1986 of the fringe hypothesis that Japan had already created a nuclear weapon, by Department of Energy employee Roger M. Anders, appeared in the journal Military Affairs:

Journalist Wilcox's book describes the Japanese wartime atomic energy projects. This is laudable, in that it illuminates a little-known episode; nevertheless, the work is marred by Wilcox's seeming eagerness to show that Japan created an atomic bomb. Tales of Japanese atomic explosions, one a fictional attack on Los Angeles, the other an unsubstantiated account of a post-Hiroshima test, begin the book. (Wilcox accepts the test story because the author [Snell], "was a distinguished journalist"). The tales, combined with Wilcox's failure to discuss the difficulty of translating scientific theory into a workable bomb, obscure the actual story of the Japanese effort: uncoordinated laboratory-scale projects which took paths least likely to produce a bomb.

Other

Truman felt that the effects of Japan witnessing a failed test would be too great of a risk to arrange such a demonstration.

It emerged after the war that, had Japan not surrendered in August 1945, it was planning to attack the United States with biological weapons in September.

Opposition

Militarily unnecessary

Assistant

Secretary Bard was convinced that a standard bombardment and naval

blockade would be enough to force Japan into surrendering. Even more, he

had seen signs for weeks that the Japanese were actually already

looking for a way out of the war. His idea was for the United States to

tell the Japanese about the bomb, the impending Soviet entry into the

war, and the fair treatment that citizens and the Emperor would receive

at the coming Big Three conference.

Before the bombing occurred, Bard pleaded with Truman to neither drop

the bombs (at least not without warning the population first) nor to

invade the entire country, proposing to stop the bloodshed.

The 1946 United States Strategic Bombing Survey in Japan, whose members included Paul Nitze,

concluded the atomic bombs had been unnecessary to win the war. After

reviewing numerous documents, and interviewing hundreds of Japanese

civilian and military leaders after Japan surrendered, they reported:

There is little point in attempting precisely to impute Japan's unconditional surrender to any one of the numerous causes which jointly and cumulatively were responsible for Japan's disaster. The time lapse between military impotence and political acceptance of the inevitable might have been shorter had the political structure of Japan permitted a more rapid and decisive determination of national policies. Nevertheless, it seems clear that, even without the atomic bombing attacks, air supremacy over Japan could have exerted sufficient pressure to bring about unconditional surrender and obviate the need for invasion.

Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.

This conclusion assumed conventional fire bombing would have

continued, with ever-increasing numbers of B-29s, and a greater level of

destruction to Japan's cities and population. One of Nitze's most influential sources was Prince Fumimaro Konoe,

who responded to a question asking whether Japan would have surrendered

if the atomic bombs had not been dropped by saying resistance would

have continued through November or December 1945.

Historians such as Bernstein, Hasegawa, and Newman have

criticized Nitze for drawing a conclusion they say went far beyond what

the available evidence warranted, in order to promote the reputation of

the Air Force at the expense of the Army and Navy.

Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote in his memoir The White House Years:

In 1945 Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.

Other U.S. military officers who disagreed with the necessity of the bombings include General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy

(the Chief of Staff to the President), Brigadier General Carter Clarke

(the military intelligence officer who prepared intercepted Japanese

cables for U.S. officials), Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet), Fleet Admiral William Halsey Jr.

(Commander of the US Third Fleet), and even the man in charge of all

strategic air operations against the Japanese home islands, then-Major

General Curtis LeMay:

The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military point of view, in the defeat of Japan.

— Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet,

The use of [the atomic bombs] at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons ... The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.

— Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Truman, 1950

The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.

— Major General Curtis LeMay, XXI Bomber Command, September 1945,

The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment ... It was a mistake to ever drop it ... [the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it.

— Fleet Admiral William Halsey Jr., 1946,

Stephen Peter Rosen of Harvard believes that a submarine blockade would have been sufficient to force Japan to surrender.

Historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa wrote the atomic bombings themselves were not the principal reason for Japan's capitulation. Instead, he contends, it was the Soviet entry in the war on 8 August, allowed by the Potsdam Declaration

signed by the other Allies. The fact the Soviet Union did not sign this

declaration gave Japan reason to believe the Soviets could be kept out

of the war.

As late as 25 July, the day before the declaration was issued, Japan

had asked for a diplomatic envoy led by Konoe to come to Moscow hoping

to mediate peace in the Pacific. Konoe was supposed to bring a letter from the Emperor stating:

His Majesty the Emperor, mindful of the fact that the present war daily brings greater evil and sacrifice of the peoples of all the belligerent powers, desires from his heart that it may be quickly terminated. But as long as England and the United States insist upon unconditional surrender the Japanese Empire has no alternative to fight on with all its strength for the honour and existence of the Motherland ... It is the Emperor's private intention to send Prince Konoe to Moscow as a Special Envoy ...

Hasegawa's view is, when the Soviet Union declared war on 8 August,

it crushed all hope in Japan's leading circles that the Soviets could

be kept out of the war and also that reinforcements from Asia to the

Japanese islands would be possible for the expected invasion. Hasegawa wrote:

On the basis of available evidence, however, it is clear that the two atomic bombs ... alone were not decisive in inducing Japan to surrender. Despite their destructive power, the atomic bombs were not sufficient to change the direction of Japanese diplomacy. The Soviet invasion was. Without the Soviet entry in the war, the Japanese would have continued to fight until numerous atomic bombs, a successful allied invasion of the home islands, or continued aerial bombardments, combined with a naval blockade, rendered them incapable of doing so.

Ward Wilson

wrote that "after Nagasaki was bombed only four major cities remained

which could readily have been hit with atomic weapons", and that the

Japanese Supreme Council did not bother to convene after the atomic

bombings because they were barely more destructive than previous

bombings. He wrote that instead, the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria and South Sakhalin removed Japan's last diplomatic and military options for negotiating a conditional

surrender, and this is what prompted Japan's surrender. He wrote that

attributing Japan's surrender to a "miracle weapon", instead of the

start of the Soviet invasion, saved face for Japan and enhanced the

United States' world standing.

Bombings as war crimes

Nowhere

is this troubled sense of responsibility more acute, and surely nowhere

has it been more prolix, than among those who participated in the

development of atomic energy for military purposes. ... In some sort of

crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no over-statement can quite

extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which

they cannot lose.

—Robert Oppenheimer1947 Arthur D. Little Memorial Lecture

A number of notable individuals and organizations have criticized the bombings, many of them characterizing them as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and/or state terrorism. Early critics of the bombings were Albert Einstein, Eugene Wigner and Leó Szilárd, who had together spurred the first bomb research in 1939 with a jointly written letter to President Roosevelt.

Szilárd, who had gone on to play a major role in the Manhattan Project, argued:

Let me say only this much to the moral issue involved: Suppose Germany had developed two bombs before we had any bombs. And suppose Germany had dropped one bomb, say, on Rochester and the other on Buffalo, and then having run out of bombs she would have lost the war. Can anyone doubt that we would then have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and that we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them?

The cenotaph at the Hiroshima Peace Park is inscribed with the sentence: "Let all the souls here rest in peace; this mistake shall not be repeated." Although the sentence may seem ambiguous, it has been clarified that its intended agent is all of humanity, and the mistake referred to is war in general.

A number of scientists who worked on the bomb were against its use. Led by Dr. James Franck, seven scientists submitted a report to the Interim Committee (which advised the President) in May 1945, saying:

If the United States were to be the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction upon mankind, she would sacrifice public support throughout the world, precipitate the race for armaments, and prejudice the possibility of reaching an international agreement on the future control of such weapons.

Mark Selden

writes, "Perhaps the most trenchant contemporary critique of the

American moral position on the bomb and the scales of justice in the war

was voiced by the Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal, a dissenting voice at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, who balked at accepting the uniqueness of Japanese war crimes. Recalling Kaiser Wilhelm II's account of his duty to bring World War I

to a swift end—"everything must be put to fire and sword; men, women

and children and old men must be slaughtered and not a tree or house be

left standing." Pal observed:

This policy of indiscriminate murder to shorten the war was considered to be a crime. In the Pacific war under our consideration, if there was anything approaching what is indicated in the above letter of the German Emperor, it is the decision coming from the Allied powers to use the bomb. Future generations will judge this dire decision ... If any indiscriminate destruction of civilian life and property is still illegal in warfare, then, in the Pacific War, this decision to use the atom bomb is the only near approach to the directives of the German Emperor during the first World War and of the Nazi leaders during the second World War.

Selden mentions another critique of the nuclear bombing, which he

says the U.S. government effectively suppressed for twenty-five years,

as worth mention. On 11 August 1945, the Japanese government filed an

official protest over the atomic bombing to the U.S. State Department

through the Swiss Legation in Tokyo, observing:

Combatant and noncombatant men and women, old and young, are massacred without discrimination by the atmospheric pressure of the explosion, as well as by the radiating heat which result therefrom. Consequently there is involved a bomb having the most cruel effects humanity has ever known ... The bombs in question, used by the Americans, by their cruelty and by their terrorizing effects, surpass by far gas or any other arm, the use of which is prohibited. Japanese protests against U.S. desecration of international principles of war paired the use of the atomic bomb with the earlier firebombing, which massacred old people, women and children, destroying and burning down Shinto and Buddhist temples, schools, hospitals, living quarters, etc ... They now use this new bomb, having an uncontrollable and cruel effect much greater than any other arms or projectiles ever used to date. This constitutes a new crime against humanity and civilization.

Selden concludes, despite the war crimes committed by the Empire of

Japan, nevertheless, "the Japanese protest correctly pointed to U.S.

violations of internationally accepted principles of war with respect to

the wholesale destruction of populations".

In 1963, the bombings were the subject of a judicial review in Ryuichi Shimoda et al. v. The State.

On the 22nd anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the District

Court of Tokyo declined to rule on the legality of nuclear weapons in

general, but found, "the attacks upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused such

severe and indiscriminate suffering that they did violate the most

basic legal principles governing the conduct of war."

In the opinion of the court, the act of dropping an atomic bomb

on cities was at the time governed by international law found in the Hague Regulations on Land Warfare of 1907 and the Hague Draft Rules of Air Warfare of 1922–1923 and was therefore illegal.

In the documentary The Fog of War, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara recalls General Curtis LeMay, who relayed the Presidential order to drop nuclear bombs on Japan, said:

"If we'd lost the war, we'd all have been prosecuted as war criminals." And I think he's right. He, and I'd say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?

As the first combat use of nuclear weapons, the bombings of Hiroshima

and Nagasaki represent to some the crossing of a crucial barrier. Peter Kuznick, director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University, wrote of President Truman: "He knew he was beginning the process of annihilation of the species." Kuznick said the atomic bombing of Japan "was not just a war crime; it was a crime against humanity."

Takashi Hiraoka, mayor of Hiroshima, upholding nuclear disarmament, said in a hearing to The Hague International Court of Justice

(ICJ): "It is clear that the use of nuclear weapons, which cause

indiscriminate mass murder that leaves [effects on] survivors for

decades, is a violation of international law". Iccho Itoh, the mayor of Nagasaki, declared in the same hearing:

It is said that the descendants of the atomic bomb survivors will have to be monitored for several generations to clarify the genetic impact, which means that the descendants will live in anxiety for [decades] to come ... with their colossal power and capacity for slaughter and destruction, nuclear weapons make no distinction between combatants and non-combatants or between military installations and civilian communities ... The use of nuclear weapons ... therefore is a manifest infraction of international law.

Although bombings do not meet the definition of genocide, some consider the definition too strict, and argue the bombings do constitute genocide. For example, University of Chicago historian Bruce Cumings states there is a consensus among historians to Martin Sherwin's statement, "[T]he Nagasaki bomb was gratuitous at best and genocidal at worst".

The scholar R. J. Rummel instead extends the definition of genocide to what he calls democide,

and includes the major part of deaths from the atom bombings in these.

His definition of democide includes not only genocide, but also an

excessive killing of civilians in war, to the extent this is against the

agreed rules for warfare; he argues the bombings of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki were war crimes, and thus democide.

Rummel quotes among others an official protest from the US government in

1938 to Japan, for its bombing of Chinese cities: "The bombing of

non-combatant populations violated international and humanitarian laws."

He also considers excess deaths of civilians in conflagrations caused by conventional means, such as in Tokyo, as acts of democide.

In 1967, Noam Chomsky

described the atomic bombings as "among the most unspeakable crimes in

history". Chomsky pointed to the complicity of the American people in

the bombings, referring to the bitter experiences they had undergone

prior to the event as the cause for their acceptance of its legitimacy.

In 2007, a group of intellectuals in Hiroshima established an

unofficial body called International Peoples' Tribunal on the Dropping

of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On 16 July 2007, it delivered

its verdict, stating:

The Tribunal finds that the nature of damage caused by the atomic bombs can be described as indiscriminate extermination of all life forms or inflicting unnecessary pain to the survivors.

About the legality and the morality of the action, the unofficial tribunal found:

The ... use of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was illegal in the light of the principles and rules of International Humanitarian Law applicable in armed conflicts, since the bombing of both cities, made civilians the object of attack, using nuclear weapons that were incapable of distinguishing between civilians and military targets and consequently, caused unnecessary suffering to the civilian survivors.

State terrorism

Historical

accounts indicate the decision to use the atomic bombs was made in

order to provoke a surrender of Japan by use of an awe-inspiring power.

These observations have caused Michael Walzer

to state the incident was an act of "war terrorism: the effort to kill

civilians in such large numbers that their government is forced to

surrender. Hiroshima seems to me the classic case."

This type of claim eventually prompted historian Robert P. Newman, a supporter of the bombings, to say "there can be justified terror, as there can be just wars".

Certain scholars and historians have characterized the atomic bombings of Japan as a form of "state terrorism". This interpretation is based on a definition of terrorism as "the targeting of innocents to achieve a political goal". As Frances V. Harbour points out, the meeting of the Target Committee in Los Alamos on 10 and 11 May 1945 suggested targeting the large population centers of Kyoto or Hiroshima for a "psychological effect" and to make "the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized". As such, Professor Harbour suggests the goal was to create terror for political ends both in and beyond Japan. However, Burleigh Taylor Wilkins believes it stretches the meaning of "terrorism" to include wartime acts.

Historian Howard Zinn wrote that the bombings were terrorism. Zinn cites the sociologist Kai Erikson who said that the bombings could not be called "combat" because they targeted civilians. Just War theorist Michael Walzer

said that while taking the lives of civilians can be justified under

conditions of 'supreme emergency', the war situation at that time did

not constitute such an emergency.

Tony Coady, Frances V. Harbour, and Jamal Nassar

also view the targeting of civilians during the bombings as a form of

terrorism. Nassar classifies the atomic bombings as terrorism in the

same vein as the firebombing of Tokyo, the firebombing of Dresden, and the Holocaust.

Richard A. Falk, professor Emeritus of International Law and Practice at Princeton University has written in detail about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as instances of state terrorism.

He said that "the explicit function of the attacks was to terrorize the

population through mass slaughter and to confront its leaders with the

prospect of national annihilation".

Author Steven Poole

said that the "people killed by terrorism" are not the targets of the

intended terror effect. He said that the atomic bombings were "designed

as an awful demonstration" aimed at Stalin and the government of Japan.

Alexander Werth, historian and BBC

Eastern Front war correspondent, suggests that the nuclear bombing of

Japan mainly served to demonstrate the new weapon in the most shocking

way, virtually at the Soviet Union's doorstep, in order to prepare the

political post-war field.

Fundamentally immoral

The Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano expressed regret in August 1945 that the bomb's inventors did not destroy the weapon for the benefit of humanity. Rev. Cuthbert Thicknesse, the Dean of St Albans, prohibited using St Albans Abbey for a thanksgiving service for the war's end, calling the use of atomic weapons "an act of wholesale, indiscriminate massacre". In 1946, a report by the Federal Council of Churches entitled Atomic Warfare and the Christian Faith, includes the following passage:

As American Christians, we are deeply penitent for the irresponsible use already made of the atomic bomb. We are agreed that, whatever be one's judgment of the war in principle, the surprise bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are morally indefensible.

The bombers' chaplain, Father George Benedict Zabelka, would later renounce the bombings after visiting Nagasaki with two fellow chaplains.

Continuation of previous behavior

American historian Gabriel Kolko

said certain discussion regarding the moral dimension of the attacks is

wrong-headed, given the fundamental moral decision had already been

made:

During November 1944 American B-29s began their first incendiary bomb raids on Tokyo, and on 9 March 1945, wave upon wave dropped masses of small incendiaries containing an early version of napalm on the city's population—for they directed this assault against civilians. Soon small fires spread, connected, grew into a vast firestorm that sucked the oxygen out of the lower atmosphere. The bomb raid was a 'success' for the Americans; they killed 125,000 Japanese in one attack. The Allies bombed Hamburg and Dresden in the same manner, and Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, and Tokyo again on May 24. The basic moral decision that the Americans had to make during the war was whether or not they would violate international law by indiscriminately attacking and destroying civilians, and they resolved that dilemma within the context of conventional weapons. Neither fanfare nor hesitation accompanied their choice, and in fact the atomic bomb used against Hiroshima was less lethal than massive fire bombing. The war had so brutalized the American leaders that burning vast numbers of civilians no longer posed a real predicament by the spring of 1945. Given the anticipated power of the atomic bomb, which was far less than that of fire bombing, no one expected small quantities of it to end the war. Only its technique was novel—nothing more. By June 1945 the mass destruction of civilians via strategic bombing did impress Stimson as something of a moral problem, but the thought no sooner arose than he forgot it, and in no appreciable manner did it shape American use of conventional or atomic bombs. "I did not want to have the United States get the reputation of outdoing Hitler in atrocities", he noted telling the President on June 6. There was another difficulty posed by mass conventional bombing, and that was its very success, a success that made the two modes of human destruction qualitatively identical in fact and in the minds of the American military. "I was a little fearful", Stimson told Truman, "that before we could get ready the Air Force might have Japan so thoroughly bombed out that the new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength." To this the President "laughed and said he understood."

Nagasaki bombing unnecessary

The black marker indicates "ground zero" of the Nagasaki atomic bomb explosion.

The second atomic bombing, on Nagasaki, came only three days after

the bombing of Hiroshima, when the devastation at Hiroshima had yet to

be fully comprehended by the Japanese. The lack of time between the bombings has led some historians to state that the second bombing was "certainly unnecessary", "gratuitous at best and genocidal at worst", and not jus in bello. In response to the claim that the atomic bombing of Nagasaki was unnecessary, Maddox wrote:

American officials believed more than one bomb would be necessary because they assumed Japanese hard-liners would minimize the first explosion or attempt to explain it away as some sort of natural catastrophe, which is precisely what they did. In the three days between the bombings, the Japanese minister of war, for instance, refused even to admit that the Hiroshima bomb was atomic. A few hours after Nagasaki, he told the cabinet that "the Americans appeared to have one hundred atomic bombs ... they could drop three per day. The next target might well be Tokyo."

Jerome Hagen indicates that War Minister Anami's revised briefing was

partly based on interrogating captured American pilot Marcus McDilda.

Under torture, McDilda reported that the Americans had 100 atomic bombs,

and that Tokyo and Kyoto would be the next atomic bomb targets. Both

were lies; McDilda was not involved or briefed on the Manhattan Project

and simply told the Japanese what he thought they wanted to hear.

One day before the bombing of Nagasaki, the Emperor notified

Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō of his desire to "insure a prompt ending

of hostilities". Tōgō wrote in his memoir that the Emperor "warned

[him] that since we could no longer continue the struggle, now that a

weapon of this devastating power was used against us, we should not let

slip the opportunity [to end the war] by engaging in attempts to gain

more favorable conditions". The Emperor then requested Tōgō to communicate his wishes to the Prime Minister.

Dehumanization

Historian James J. Weingartner sees a connection between the American mutilation of Japanese war dead and the bombings.

According to Weingartner both were partially the result of a

dehumanization of the enemy. "[T]he widespread image of the Japanese as

sub-human constituted an emotional context which provided another

justification for decisions which resulted in the death of hundreds of

thousands."

On the second day after the bombing of Nagasaki, President Truman had

stated: "The only language they seem to understand is the one we have

been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have

to treat him like a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless

true".

International law

At the time of the atomic bombings, there was no international treaty

or instrument protecting a civilian population specifically from attack

by aircraft. Many critics of the atomic bombings point to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 as setting rules in place regarding the attack of civilian populations. The Hague Conventions contained no specific air warfare provisions but it prohibited the targeting of undefended civilians by naval artillery, field artillery, or siege engines, all of which were classified as "bombardment".

However, the Conventions allowed the targeting of military

establishments in cities, including military depots, industrial plants,

and workshops which could be used for war. This set of rules was not followed during World War I which saw bombs dropped indiscriminately on cities by Zeppelins

and multi-engine bombers. Afterward, another series of meetings were

held at The Hague in 1922–23, but no binding agreement was reached

regarding air warfare. During the 1930s and 1940s, the aerial bombing of cities was resumed, notably by the German Condor Legion against the cities of Guernica and Durango in Spain in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War. This led to an escalation of various cities bombed, including Chongqing, Warsaw, Rotterdam, London, Coventry, Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo. All of the major belligerents in World War II dropped bombs on civilians in cities.

Modern debate over the applicability of the Hague Conventions to

the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki revolves around whether

the Conventions can be assumed to cover modes of warfare that were at

the time unknown; whether rules for artillery bombardment can be applied

to rules for aerial bombing. As well, the debate hinges on to what

degree the Hague Conventions was being followed by the warring

countries.

If the Hague Conventions is admitted as applicable, the critical

question becomes whether the bombed cities met the definition of

"undefended". Some observers consider Hiroshima and Nagasaki undefended,

some say that both cities were legitimate military targets, and others

say that Hiroshima could be considered a legitimate military target

while Nagasaki was comparatively undefended. Hiroshima has been argued as not a legitimate target because the major industrial plants were just outside the target area. It has also been argued as a legitimate target because Hiroshima was the headquarters of the regional Second General Army and Fifth Division with 40,000 combatants stationed in the city. Both cities were protected by anti-aircraft guns, which is an argument against the definition of "undefended".

The Hague Conventions prohibited poison weapons. The

radioactivity of the atomic bombings has been described as poisonous,

especially in the form of nuclear fallout which kills more slowly. However, this view was rejected by the International Court of Justice in 1996, which stated that the primary and exclusive use of (air burst) nuclear weapons is not to poison or asphyxiate and thus is not prohibited by the Geneva Protocol.

The Hague Conventions also prohibited the employment of "arms,

projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering". The

Japanese government cited this prohibition on 10 August 1945 after

submitting a letter of protest to the United States denouncing the use

of atomic bombs.

However, the prohibition only applied to weapons as lances with a

barbed head, irregularly shaped bullets, projectiles filled with glass,

the use of any substance on bullets that would tend unnecessarily to

inflame a wound inflicted by them, along with grooving bullet tips or the creation of soft point bullets by filing off the ends of the hard coating on full metal jacketed bullets.

It however did not apply to the use of explosives contained in artillery projectiles, mines, aerial torpedoes, or hand grenades.

In 1962 and in 1963, the Japanese government retracted its previous

statement by saying that there was no international law prohibiting the

use of atomic bombs.

The Hague Conventions stated that religious buildings, art and

science centers, charities, hospitals, and historic monuments were to be

spared as far as possible in a bombardment, unless they were being used

for military purposes. Critics of the atomic bombings point to many of these kinds of structures which were destroyed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

However, the Hague Conventions also stated that for the destruction of

the enemy's property to be justified, it must be "imperatively demanded

by the necessities of war".

Because of the inaccuracy of heavy bombers in World War II, it was not

practical to target military assets in cities without damage to civilian

targets.

Even after the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, no international treaty banning or condemning nuclear warfare has ever been ratified. The closest example is a resolution by the UN General Assembly

which stated that nuclear warfare was not in keeping with the UN

charter, passed in 1953 with a vote of 25 to 20, and 26 abstentions.

Impact on surrender

Varying opinions exist on the question of what role the bombings

played in Japan's surrender: some regard the bombings as the deciding

factor, others see the bombs as a minor factor, and yet others assess their importance as unknowable.

The mainstream position in the United States from 1945 through

the 1960s regarded the bombings as the decisive factor in ending the

war; commentators have termed this the "traditionalist" view, or

pejoratively the "patriotic orthodoxy".

Some, on the other hand, see the Soviet invasion of Manchuria as primary or decisive. In the US, Robert Pape and Tsuyoshi Hasegawa in particular have advanced this view, which some have found convincing, but which others have criticized.

Robert Pape also argues that:

Military vulnerability, not civilian vulnerability, accounts for Japan's decision to surrender. Japan's military position was so poor that its leaders would likely have surrendered before invasion, and at roughly the same time in August 1945, even if the United States had not employed strategic bombing or the atomic bomb. Rather than concern for the costs and risks to the population, or even Japan's overall military weakness vis-a-vis the United States, the decisive factor was Japanese leaders' recognition that their strategy for holding the most important territory at issue—the home islands—could not succeed.

In Japanese writing about the surrender, many accounts consider the

Soviet entry into the war as the primary reason or as having equal

importance with the atomic bombs, while others, such as the work of Sadao Asada, give primacy to the atomic bombings, particularly their impact on the emperor.

The primacy of the Soviet entry as a reason for surrender is a

long-standing view among some Japanese historians, and has appeared in

some Japanese junior high school textbooks. Notably however, the Soviet Navy was well regarded as chronically lacking the naval capability to invade the home islands of Japan, despite having received numerous ships under loan from the US.

The argument about the Soviet role in Japan's surrender has a

connection with the argument about the Soviet role in America's decision

to drop the bomb:

both arguments emphasize the importance of the Soviet Union. The former

suggests that Japan surrendered to the US out of fear of the Soviet

Union, and the latter emphasizes that the US dropped the bombs to

intimidate the Soviet Union. Soviet accounts of the ending of the war

emphasised the role of the Soviet Union. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia summarised events thus:

In August 1945 American military air forces dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima (6 August) and of Nagasaki (9 August). These bombings were not caused by military necessity, and served primarily political aims. They inflicted enormous damage on the peaceable population.

Fulfilling the obligations entered into by agreement with its allies and aiming for a very speedy ending of the second world war, the Soviet government on 8 August 1945 declared that from 9 August 1945 the USSR would be in a state of war against [Japan], and associated itself with the 1945 Potsdam declaration ... of the governments of the USA, Great Britain and China of 26 July 1945, which demanded the unconditional capitulation of [Japan] and foreshadowed the bases of its subsequent demilitarization and democratization. The attack by Soviet forces, smashing the Kwantung Army and liberating Manchuria, Northern Korea, Southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, led to the rapid conclusion of the war in the Far East. On 2 September 1945 [Japan] signed the act of unconditional capitulation.

However contrary to the narrative presented by the Soviet Encyclopedia, Japan had already declared its surrender 3 days before the August 18th Soviet invasion of the Kuril Islands, where Soviet forces received comparatively little military opposition due to the earlier declaration of surrender.

Still others have argued that war-weary Japan would likely have

surrendered regardless, due to a collapse of the economy, lack of army,

food, and industrial materials, threat of internal revolution, and talk

of surrender since earlier in the year, while others find this unlikely,

arguing that Japan may well have, or likely would have, put up a

spirited resistance.

The Japanese historian Sadao Asada argues that the ultimate

decision to surrender was a personal decision by the emperor, influenced

by the atomic bombings.

Atomic diplomacy

A further argument, discussed under the rubric of "atomic diplomacy" and advanced in a 1965 book of that name by Gar Alperovitz, is that the bombings had as primary purpose to intimidate the Soviet Union, being the opening shots of the Cold War. Along these lines some

argue that the United States raced the Soviet Union and hoped to drop

the bombs and receive surrender from Japan before a Soviet entry into

the Pacific War.

However, the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom

came to an agreement at the Yalta Conference

on when the Soviet Union should join the war against Japan, and on how

the territory of Japan was to be divided at the end of the war.

Others argue that such considerations played little or no role,

the United States being instead concerned with the surrender of Japan,

and in fact that the United States desired and appreciated the Soviet

entry into the Pacific War, as it hastened the surrender of Japan.

In his memoirs Truman wrote: "There were many reasons for my going to

Potsdam, but the most urgent, to my mind, was to get from Stalin a

personal reaffirmation of Russia's entry into the war against Japan, a

matter which our military chiefs were most anxious to clinch. This I was

able to get from Stalin in the very first days of the conference."

Campbell Craig and Fredrik Logevall argue the two bombs were dropped for different reasons:

Truman's disinclination to delay the second bombing brings the Soviet factor back into consideration. What the destruction of Nagasaki accomplished was Japan's immediate surrender, and for Truman this swift capitulation was crucial in order to preempt a Soviet military move into Asia. ... In short, the first bomb was dropped as soon as it was ready, and for the reason the administration expressed: to hasten the end of the Pacific War. But in the case of the second bomb, timing was everything. In an important sense, the destruction of Nagasaki—not the bombing itself but Truman's refusal to delay it—was America's first act of the Cold War.

US public opinion on the bombings

The Pew Research Center conducted a 2015 survey showing that 56% of Americans supported the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and 34% opposed.

The study highlighted the impact of the respondents' generations,

showing that support for the bombings was 70% among Americans 65 and

older but only 47% for those between 18 and 29. Political leanings also

impacted responses, according to the survey; support was measured at 74%

for Republicans and 52% for Democrats.

American approval of the bombings has decreased steadily since 1945, when a Gallup poll showed 85% support while only 10% disapproved. Forty-five years later, in 1990, Gallup conducted another poll and found 53% support and 41% opposition.

Another Gallup poll in 2005 echoed the findings of the 2015 Pew

Research Center study by finding 57% support with 38% opposition.

While the poll data from the Pew Research Center and Gallup show a

stark drop in support for the bombings over the last half-century, Stanford

political scientists have conducted research supporting their

hypothesis that American public support for the use of nuclear force

would be just as high today as in 1945 if a similar yet contemporary

scenario presented itself.

In a 2017 study conducted by political scientists Scott D. Sagan

and Benjamin A. Valentino, respondents were asked if they would support

a conventional strike with use of atomic force in a hypothetical

situation that kills 100,000 Iranian civilians versus an invasion that

would kill 20,000 American soldiers. The results showed that 67% of

Americans supported the use of the atomic bomb in such a situation.

However, a 2010 Pew survey showed that 64% of Americans approved of

Barack Obama’s declaration that the US would abstain from the use of

nuclear weapons against nations that did not have them, showing that

many Americans may have a somewhat conflicting view on the use of atomic

force.