A map of world economies by size of GDP (nominal) in USD, World Bank, 2014

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced in a specific time period.

GDP (nominal) per capita does not, however, reflect differences in the cost of living and the inflation rates of the countries; therefore using a basis of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) is arguably more useful when comparing living standards between nations, while nominal GDP is more useful comparing national economies on the international market.

The OECD defines GDP as "an aggregate measure of production equal to the sum of the gross values added

of all resident and institutional units engaged in production and

services (plus any taxes, and minus any subsidies, on products not

included in the value of their outputs)." An IMF

publication states that, "GDP measures the monetary value of final

goods and services—that are bought by the final user—produced in a

country in a given period of time (say a quarter or a year)."

Total GDP can also be broken down into the contribution of each industry or sector of the economy. The ratio of GDP to the total population of the region is the per capita GDP

and the same is called Mean Standard of Living. GDP is considered the

"world's most powerful statistical indicator of national development and

progress".

History

William Petty came up with a basic concept of GDP to attack landlords against unfair taxation during warfare between the Dutch and the English between 1654 and 1676. Charles Davenant developed the method further in 1695. The modern concept of GDP was first developed by Simon Kuznets for a US Congress report in 1934. In this report, Kuznets warned against its use as a measure of welfare (see below under limitations and criticisms). After the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, GDP became the main tool for measuring a country's economy. At that time gross national product

(GNP) was the preferred estimate, which differed from GDP in that it

measured production by a country's citizens at home and abroad rather

than its 'resident institutional units' (see OECD

definition above). The switch from GNP to GDP in the US was in 1991,

trailing behind most other nations. The role that measurements of GDP

played in World War II was crucial to the subsequent political

acceptance of GDP values as indicators of national development and

progress. A crucial role was played here by the US Department of Commerce under Milton Gilbert where ideas from Kuznets were embedded into institutions.

The history of the concept of GDP should be distinguished from

the history of changes in ways of estimating it. The value added by

firms is relatively easy to calculate from their accounts, but the value

added by the public sector, by financial industries, and by intangible asset

creation is more complex. These activities are increasingly important

in developed economies, and the international conventions governing

their estimation and their inclusion or exclusion in GDP regularly

change in an attempt to keep up with industrial advances. In the words

of one academic economist "The actual number for GDP is therefore the

product of a vast patchwork of statistics and a complicated set of

processes carried out on the raw data to fit them to the conceptual

framework."

Determining gross domestic product (GDP)

An infographic explaining how GDP is calculated in the UK

GDP can be determined in three ways, all of which should,

theoretically, give the same result. They are the production (or output

or value added) approach, the income approach, or the speculated

expenditure approach.

The most direct of the three is the production approach, which

sums the outputs of every class of enterprise to arrive at the total.

The expenditure approach works on the principle that all of the product

must be bought by somebody, therefore the value of the total product

must be equal to people's total expenditures in buying things. The

income approach works on the principle that the incomes of the

productive factors ("producers," colloquially) must be equal to the

value of their product, and determines GDP by finding the sum of all

producers' incomes.

Production approach

This approach mirrors the OECD definition given above.

- Estimate the gross value of domestic output out of the many various economic activities;

- Determine the intermediate consumption, i.e., the cost of material, supplies and services used to produce final goods or services.

- Deduct intermediate consumption from gross value to obtain the gross value added.

Gross value added = gross value of output – value of intermediate consumption.

Value of output = value of the total sales of goods and services plus value of changes in the inventory.

The sum of the gross value added in the various economic activities is known as "GDP at factor cost".

GDP at factor cost plus indirect taxes less subsidies on products = "GDP at producer price".

For measuring output of domestic product, economic activities

(i.e. industries) are classified into various sectors. After classifying

economic activities, the output of each sector is calculated by any of

the following two methods:

- By multiplying the output of each sector by their respective market price and adding them together

- By collecting data on gross sales and inventories from the records of companies and adding them together

The value of output of all sectors is then added to get the gross

value of output at factor cost. Subtracting each sector's intermediate

consumption from gross output value gives the GVA (=GDP) at factor cost.

Adding indirect tax minus subsidies to GVA (GDP) at factor cost gives

the "GVA (GDP) at producer prices".

Income approach

The second way of estimating GDP is to use "the sum of primary incomes distributed by resident producer units".

If GDP is calculated this way it is sometimes called gross

domestic income (GDI), or GDP (I). GDI should provide the same amount as

the expenditure method described later. By definition, GDI is equal to

GDP. In practice, however, measurement errors will make the two figures

slightly off when reported by national statistical agencies.

This method measures GDP by adding incomes that firms pay

households for factors of production they hire - wages for labour,

interest for capital, rent for land and profits for entrepreneurship.

The US "National Income and Expenditure Accounts" divide incomes into five categories:

- Wages, salaries, and supplementary labour income

- Corporate profits

- Interest and miscellaneous investment income

- Farmers' incomes

- Income from non-farm unincorporated businesses

These five income components sum to net domestic income at factor cost.

Two adjustments must be made to get GDP:

- Indirect taxes minus subsidies are added to get from factor cost to market prices.

- Depreciation (or capital consumption allowance) is added to get from net domestic product to gross domestic product.

Total income can be subdivided according to various schemes, leading

to various formulae for GDP measured by the income approach. A common

one is:

- GDP = compensation of employees + gross operating surplus + gross mixed income + taxes less subsidies on production and imports

- GDP = COE + GOS + GMI + TP & M – SP & M

- Compensation of employees (COE) measures the total remuneration to employees for work done. It includes wages and salaries, as well as employer contributions to social security and other such programs.

- Gross operating surplus (GOS) is the surplus due to owners of incorporated businesses. Often called profits, although only a subset of total costs are subtracted from gross output to calculate GOS.

- Gross mixed income (GMI) is the same measure as GOS, but for unincorporated businesses. This often includes most small businesses.

The sum of COE, GOS and GMI is called total

factor income; it is the income of all of the factors of production in

society. It measures the value of GDP at factor (basic) prices. The

difference between basic prices and final prices (those used in the

expenditure calculation) is the total taxes and subsidies that the

government has levied or paid on that production. So adding taxes less

subsidies on production and imports converts GDP(I) at factor cost to GDP(I) at final prices.

Total factor income is also sometimes expressed as:

- Total factor income = employee compensation + corporate profits + proprietor's income + rental income + net interest

Expenditure approach

The

third way to estimate GDP is to calculate the sum of the final uses of

goods and services (all uses except intermediate consumption) measured

in purchasers' prices.

Market goods which are produced are purchased by someone. In the

case where a good is produced and unsold, the standard accounting

convention is that the producer has bought the good from themselves.

Therefore, measuring the total expenditure used to buy things is a way

of measuring production. This is known as the expenditure method of

calculating GDP.

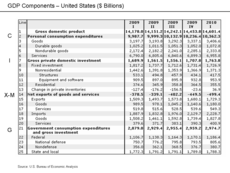

Components of GDP by expenditure

U.S. GDP computed on the expenditure basis.

GDP (Y) is the sum of consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

- Y = C + I + G + (X − M)

Here is a description of each GDP component:

- C (consumption) is normally the largest GDP component in the economy, consisting of private expenditures in the economy (household final consumption expenditure). These personal expenditures fall under one of the following categories: durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. Examples include food, rent, jewelry, gasoline, and medical expenses, but not the purchase of new housing.

- I (investment) includes, for instance, business investment in equipment, but does not include exchanges of existing assets. Examples include construction of a new mine, purchase of software, or purchase of machinery and equipment for a factory. Spending by households (not government) on new houses is also included in investment. In contrast to its colloquial meaning, "investment" in GDP does not mean purchases of financial products. Buying financial products is classed as 'saving', as opposed to investment. This avoids double-counting: if one buys shares in a company, and the company uses the money received to buy plant, equipment, etc., the amount will be counted toward GDP when the company spends the money on those things; to also count it when one gives it to the company would be to count two times an amount that only corresponds to one group of products. Buying bonds or stocks is a swapping of deeds, a transfer of claims on future production, not directly an expenditure on products.

- G (government spending) is the sum of government expenditures on final goods and services. It includes salaries of public servants, purchases of weapons for the military and any investment expenditure by a government. It does not include any transfer payments, such as social security or unemployment benefits.

- X (exports) represents gross exports. GDP captures the amount a country produces, including goods and services produced for other nations' consumption, therefore exports are added.

- M (imports) represents gross imports. Imports are subtracted since imported goods will be included in the terms G, I, or C, and must be deducted to avoid counting foreign supply as domestic.

Note that C, G, and I are expenditures on final goods

and services; expenditures on intermediate goods and services do not

count. (Intermediate goods and services are those used by businesses to

produce other goods and services within the accounting year.)

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, which is

responsible for calculating the national accounts in the United States,

"In general, the source data for the expenditures components are

considered more reliable than those for the income components [see

income method, above]."

GDP vs GNI

GDP can be contrasted with gross national product (GNP) or, as it is now known, gross national income

(GNI). The difference is that GDP defines its scope according to

location, while GNI defines its scope according to ownership. In a

global context, world GDP and world GNI are, therefore, equivalent terms.

GDP is product produced within a country's borders; GNI is

product produced by enterprises owned by a country's citizens. The two

would be the same if all of the productive enterprises in a country were

owned by its own citizens, and those citizens did not own productive

enterprises in any other countries. In practice, however, foreign

ownership makes GDP and GNI non-identical. Production within a country's

borders, but by an enterprise owned by somebody outside the country,

counts as part of its GDP but not its GNI; on the other hand, production

by an enterprise located outside the country, but owned by one of its

citizens, counts as part of its GNI but not its GDP.

For example, the GNI of the USA

is the value of output produced by American-owned firms, regardless of

where the firms are located. Similarly, if a country becomes

increasingly in debt, and spends large amounts of income servicing this

debt this will be reflected in a decreased GNI but not a decreased GDP.

Similarly, if a country sells off its resources to entities outside

their country this will also be reflected over time in decreased GNI,

but not decreased GDP. This would make the use of GDP more attractive

for politicians in countries with increasing national debt and

decreasing assets.

Gross national income (GNI) equals GDP plus income receipts from

the rest of the world minus income payments to the rest of the world.

In 1991, the United States switched from using GNP to using GDP as its primary measure of production.

The relationship between United States GDP and GNP is shown in table 1.7.5 of the National Income and Product Accounts.

International standards

The international standard for measuring GDP is contained in the book System of National Accounts (1993), which was prepared by representatives of the International Monetary Fund, European Union, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations and World Bank. The publication is normally referred to as SNA93 to distinguish it from the previous edition published in 1968 (called SNA68).

SNA93 provides a set of rules and procedures for the measurement

of national accounts. The standards are designed to be flexible, to

allow for differences in local statistical needs and conditions.

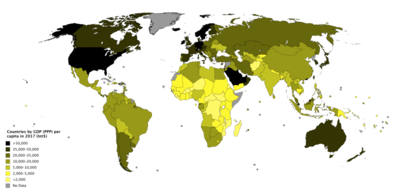

National measurement

Countries by GDP (PPP) per capita (Int$) in 2017 according to the IMF

|

> 50,000

35,000–50,000

20,000–35,000

10,000–20,000

|

5,000–10,000

2,000–5,000

< 2,000

No data

|

Countries by 2018 GDP (nominal) per capita

|

>$60,000

$50,000 - $60,000

$40,000 - $50,000

$30,000 - $40,000

|

$20,000 - $30,000

$10,000 - $20,000

$5,000 - $10,000

$2,500 - $5,000

|

$1,000 - $2,500

<$1,000

|

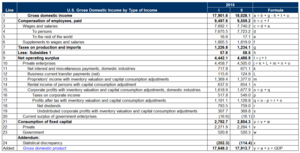

U.S GDP computed on the income basis

Within each country GDP is normally measured by a national government

statistical agency, as private sector organizations normally do not

have access to the information required (especially information on

expenditure and production by governments).

Nominal GDP and adjustments to GDP

The

raw GDP figure as given by the equations above is called the nominal,

historical, or current, GDP. When one compares GDP figures from one year

to another, it is desirable to compensate for changes in the value of

money – for the effects of inflation or deflation. To make it more

meaningful for year-to-year comparisons, it may be multiplied by the

ratio between the value of money in the year the GDP was measured and

the value of money in a base year.

For example, suppose a country's GDP in 1990 was $100 million and

its GDP in 2000 was $300 million. Suppose also that inflation had

halved the value of its currency over that period. To meaningfully

compare its GDP in 2000 to its GDP in 1990, we could multiply the GDP in

2000 by one-half, to make it relative to 1990 as a base year. The

result would be that the GDP in 2000 equals $300 million × one-half =

$150 million, in 1990 monetary terms. We would see that the country's GDP had realistically increased 50 percent

over that period, not 200 percent, as it might appear from the raw GDP

data. The GDP adjusted for changes in money value in this way is called

the real, or constant, GDP.

The factor used to convert GDP from current to constant values in this way is called the GDP deflator. Unlike consumer price index,

which measures inflation or deflation in the price of household

consumer goods, the GDP deflator measures changes in the prices of all

domestically produced goods and services in an economy including

investment goods and government services, as well as household

consumption goods.

Constant-GDP figures allow us to calculate a GDP growth rate,

which indicates how much a country's production has increased (or

decreased, if the growth rate is negative) compared to the previous

year.

-

- Real GDP growth rate for year n

- = [(Real GDP in year n) − (Real GDP in year n − 1)] / (Real GDP in year n − 1)

Another thing that it may be desirable to account for is population

growth. If a country's GDP doubled over a certain period, but its

population tripled, the increase in GDP may not mean that the standard

of living increased for the country's residents; the average person in

the country is producing less than they were before. Per-capita GDP is a measure to account for population growth.

Cross-border comparison and purchasing power parity

The level of GDP in countries may be compared by converting their value in national currency according to either the current currency exchange rate, or the purchasing power parity exchange rate.

- Current currency exchange rate is the exchange rate in the international foreign exchange market.

- Purchasing power parity exchange rate is the exchange rate based on the purchasing power parity (PPP) of a currency relative to a selected standard (usually the United States dollar). This is a comparative (and theoretical) exchange rate, the only way to directly realize this rate is to sell an entire CPI basket in one country, convert the cash at the currency market rate & then rebuy that same basket of goods in the other country (with the converted cash). Going from country to country, the distribution of prices within the basket will vary; typically, non-tradable purchases will consume a greater proportion of the basket's total cost in the higher GDP country, per the Balassa-Samuelson effect.

The ranking of countries may differ significantly based on which method is used.

- The current exchange rate method converts the value of goods and services using global currency exchange rates. The method can offer better indications of a country's international purchasing power. For instance, if 10% of GDP is being spent on buying hi-tech foreign arms, the number of weapons purchased is entirely governed by current exchange rates, since arms are a traded product bought on the international market. There is no meaningful 'local' price distinct from the international price for high technology goods. The PPP method of GDP conversion is more relevant to non-traded goods and services. In the above example if hi-tech weapons are to be produced internally their amount will be governed by GDP (PPP) rather than nominal GDP.

There is a clear pattern of the purchasing power parity method decreasing the disparity in GDP between high and low income (GDP) countries, as compared to the current exchange rate method. This finding is called the Penn effect.

For more information, see Measures of national income and output.

Standard of living and GDP: wealth distribution and externalities

GDP per capita is often used as an indicator of living standards.

The major advantage of GDP per capita as an indicator of standard

of living is that it is measured frequently, widely, and consistently.

It is measured frequently in that most countries provide information on

GDP on a quarterly basis, allowing trends to be seen quickly. It is

measured widely in that some measure of GDP is available for almost

every country in the world, allowing inter-country comparisons. It is

measured consistently in that the technical definition of GDP is

relatively consistent among countries.

GDP does not include several factors that influence the standard of living. In particular, it fails to account for:

- Externalities – Economic growth may entail an increase in negative externalities that are not directly measured in GDP. Increased industrial output might grow GDP, but any pollution is not counted.

- Non-market transactions– GDP excludes activities that are not provided through the market, such as household production, bartering of goods and services, and volunteer or unpaid services.

- Non-monetary economy– GDP omits economies where no money comes into play at all, resulting in inaccurate or abnormally low GDP figures. For example, in countries with major business transactions occurring informally, portions of local economy are not easily registered. Bartering may be more prominent than the use of money, even extending to services.

- Quality improvements and inclusion of new products– by not fully adjusting for quality improvements and new products, GDP understates true economic growth. For instance, although computers today are less expensive and more powerful than computers from the past, GDP treats them as the same products by only accounting for the monetary value. The introduction of new products is also difficult to measure accurately and is not reflected in GDP despite the fact that it may increase the standard of living. For example, even the richest person in 1900 could not purchase standard products, such as antibiotics and cell phones, that an average consumer can buy today, since such modern conveniences did not exist then.

- Sustainability of growth– GDP is a measurement of economic historic activity and is not necessarily a projection.

- Wealth distribution – GDP does not account for variances in incomes of various demographic groups. See income inequality metrics for discussion of a variety of inequality-based economic measures.

It can be argued that GDP per capita as an indicator standard of

living is correlated with these factors, capturing them indirectly.

As a result, GDP per capita as a standard of living is a continued

usage because most people have a fairly accurate idea of what it is and

know it is tough to come up with quantitative measures for such

constructs as happiness, quality of life, and well-being.

Limitations and criticisms

Limitations at introduction

Simon Kuznets,

the economist who developed the first comprehensive set of measures of

national income, stated in his first report to the US Congress in 1934,

in a section titled "Uses and Abuses of National Income Measurements":

The valuable capacity of the human mind to simplify a complex situation in a compact characterization becomes dangerous when not controlled in terms of definitely stated criteria. With quantitative measurements especially, the definiteness of the result suggests, often misleadingly, a precision and simplicity in the outlines of the object measured. Measurements of national income are subject to this type of illusion and resulting abuse, especially since they deal with matters that are the center of conflict of opposing social groups where the effectiveness of an argument is often contingent upon oversimplification. [...]

All these qualifications upon estimates of national income as an index of productivity are just as important when income measurements are interpreted from the point of view of economic welfare. But in the latter case additional difficulties will be suggested to anyone who wants to penetrate below the surface of total figures and market values. Economic welfare cannot be adequately measured unless the personal distribution of income is known. And no income measurement undertakes to estimate the reverse side of income, that is, the intensity and unpleasantness of effort going into the earning of income. The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined above.

In 1962, Kuznets stated:

Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what.

Further criticisms

Ever

since the development of GDP, multiple observers have pointed out

limitations of using GDP as the overarching measure of economic and

social progress.

Many environmentalists argue that GDP is a poor measure of social progress because it does not take into account harm to the environment.

Although a high or rising level of GDP is often associated with

increased economic and social progress within a country, a number of

scholars have pointed out that this does not necessarily play out in

many instances. For example, Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen

have pointed out that an increase in GDP or in GDP growth does not

necessarily lead to a higher standard of living, particularly in areas

such as healthcare and education.

Another important area that does not necessarily improve along with GDP

is political liberty, which is most notable in China, where GDP growth

is strong yet political liberties are heavily restricted.

GDP does not account for the distribution of income among the

residents of a country, because GDP is merely an aggregate measure. An

economy may be highly developed or growing rapidly, but also contain a

wide gap between the rich and the poor in a society. These inequalities

often occur on the lines of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or other

minority status within countries.

This can lead to misleading characterizations of economic well-being if

the income distribution is heavily skewed toward the high end, as the

poorer residents will not directly benefit from the overall level of

wealth and income generated in their country. Even GDP per capita

measures may have the same downside if inequality is high. For example,

South Africa during apartheid ranked high in terms of GDP per capita,

but the benefits of this immense wealth and income were not shared

equally among the country.

GDP does not take into account the value of household and other unpaid work. Some, including Martha Nussbaum,

argue that this value should be included in measuring GDP, as household

labor is largely a substitute for goods and services that would

otherwise be purchased for value.

Even under conservative estimates, the value of unpaid labor in

Australia has been calculated to be over 50% of the country's GDP.

A later study analyzed this value in other countries, with results

ranging from a low of about 15% in Canada (using conservative estimates)

to high of nearly 70% in the United Kingdom (using more liberal

estimates). For the United States, the value was estimated to be between

about 20% on the low end to nearly 50% on the high end, depending on

the methodology being used. Because many public policies are shaped by GDP calculations and by the related field of national accounts,

the non-inclusion of unpaid work in calculating GDP can create

distortions in public policy, and some economists have advocated for

changes in the way public policies are formed and implemented.

The UK's Natural Capital Committee highlighted the shortcomings of GDP in its advice to the UK

Government in 2013, pointing out that GDP "focuses on flows, not

stocks. As a result, an economy can run down its assets yet, at the

same time, record high levels of GDP growth, until a point is reached

where the depleted assets act as a check on future growth". They then

went on to say that "it is apparent that the recorded GDP growth rate

overstates the sustainable growth rate. Broader measures of wellbeing

and wealth are needed for this and there is a danger that short-term

decisions based solely on what is currently measured by national

accounts may prove to be costly in the long-term".

It has been suggested that countries that have authoritarian governments, such as the People's Republic of China, and Russia, inflate their GDP figures.

Proposals to overcome GDP limitations

In response to these and other limitations of using GDP, alternative approaches have emerged.

- In the 1980s, Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum developed the capability approach, which focuses on the functional capabilities enjoyed by people within a country, rather than the aggregate wealth held within a country. These capabilities consist of the functions that a person is able to achieve.

- In 1990 Mahbub ul Haq, a Pakistani Economist at the United Nations, introduced the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI is a composite index of life expectancy at birth, adult literacy rate and standard of living measured as a logarithmic function of GDP, adjusted to purchasing power parity.

- In 1989, John B. Cobb and Herman Daly introduced Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) by taking into account various other factors such as consumption of nonrenewable resources and degradation of the environment. The new formula deducted from GDP (personal consumption + public non-defensive expenditures - private defensive expenditures + capital formation + services from domestic labour - costs of environmental degradation - depreciation of natural capital)

- In 2005, Med Jones, an American Economist, at the International Institute of Management, introduced the first secular Gross National Happiness Index a.k.a. Gross National Well-being framework and Index to complement GDP economics with additional seven dimensions, including environment, education, and government, work, social and health (mental and physical) indicators. The proposal was inspired by the King of Bhutan's GNH philosophy.

- In 2009 the European Union released a communication titled GDP and beyond: Measuring progress in a changing world that identified five actions to improve the indicators of progress in ways that make it more responsive to the concerns of its citizens: Introduced a proposal to complementing GDP with environmental and social indicators

- In 2009 Professors Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi at the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (CMEPSP), formed by French President, Nicolas Sarkozy published a proposal to overcome the limitation of GDP economics to expand the focus to well-being economics with wellbeing framework consisting of health, environment, work, physical safety, economic safety, political freedom.

- In 2012, the Karma Ura of the Center for Bhutan Studies published Bhutan Local GNH Index contributors to happiness—physical, mental and spiritual health; time-balance; social and community vitality; cultural vitality; education; living standards; good governance; and ecological vitality. The Bhutan GNH Index.

- In 2013 OECD Better Life Index was published by the OECD. The dimensions of the index included health, economic, workplace, income, jobs, housing, civic engagement, life satisfaction

- Since 2012, professors John Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey Sachs haved edited an annual World Happiness Report which reports a national measure of subjective well-being, derived from a single survey question on satisfaction with life. GDP explains some of the cross-national variation in life satisfaction, but more of it is explained by other, social variables (See 2013 World Happiness Report).

- In 2019, professor Serge Pierre Besanger has published a "GDP 3.0" proposal which combines an expanded GNI formula which he calls GNIX, with a Palma ratio and a set of environmental metrics based on the Daly Rule.