Generation Alpha (or Gen Alpha for short) is the demographic cohort succeeding Generation Z.

Researchers and popular media use the early 2010s as starting birth

years and the mid-2020s as ending birth years. Named after the first

letter in the Greek alphabet, Generation Alpha is the first to be born entirely in the 21st century. Most members of Generation Alpha are the children of Millennials.

Nomenclature

The name Generation Alpha

originated from a 2008 survey conducted by the Australian consulting

agency McCrindle Research, according to founder Mark McCrindle who is

generally credited with the term. McCrindle describes how his team arrived at the name in a 2015 interview:

When I was researching my book The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations (published in 2009) it became apparent that a new generation was about to commence and there was no name for them. So I conducted a survey (we’re researchers after all) to find out what people think the generation after Z should be called and while many names emerged, and Generation A was the most mentioned, Generation Alpha got some mentions too and so I settled on that for the title of the chapter Beyond Z: Meet Generation Alpha. It just made sense as it is in keeping with scientific nomenclature of using the Greek alphabet in lieu of the Latin and it didn’t make sense to go back to A, after all they are the first generation wholly born in the 21st Century and so they are the start of something new not a return to the old.

McCrindle Research also took inspiration from the naming of hurricanes, specifically the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season in which the names beginning with the letters of the Roman alphabet were exhausted, and the last six storms were named with the Greek letters alpha through zeta.

Demographics

Global trends

As of 2015, there were some two and a half million people born every

week around the globe; Generation Alpha is expected to reach two billion

by 2025.

For comparison, the United Nations estimated that the human population

was about 7.8 billion in 2020, up from 2.5 billion in 1950. Roughly

three quarters of all people reside in Africa and Asia in 2020.

In fact, most human population growth comes from these two continents,

as nations in Europe and the Americas tend to have too few children to

replace themselves.

Population pyramid of the world in 2018

2018 was the first time when the number of people above 65 years of

age (705 million) exceeded those between the ages of zero and four (680

million). In other words, this was the first year in which there were

more grandparents than grandchildren. If current trends continues, the

ratio between these two age groups will top two by 2050.

Fertility rates have been falling around the world thanks to rising

standards of living, greater access to contraceptives, and improved

educational and economic opportunities. The global average fertility

rate in 1950 was 4.7 but dropped to 2.4 in 2017. However, this average

masks the huge variation between countries. Niger has the world's

highest fertility rate at 7.1 while Cyprus has one of the lowest at 1.0.

In general, the more developed of countries, including much of Europe,

the United States, South Korea, and Australia, tend to have lower

fertility rates. People here tend to have children later and fewer of them.

Education is in fact one of the most important determinants of

fertility. The more educated a woman is, the later she tends to have

children, and fewer of them.

Increasing immigration is problematic while policies that encourage

people to have more children rarely succeed. Moreover, immigration is

not an option at the global level. At the same time, the global average life expectancy has gone from 52 in 1960 to 72 in 2017.

Half of the human population lived in urban areas in 2007, and

this figure became 55% in 2019. If the current trend continues, it will

reach two thirds by the middle of the century. A direct consequence of

urbanization is falling fertility. In rural areas, children can be

considered an asset, that is, additional labor. But in the cities,

children are a burden. Moreover, urban women demand greater autonomy and

exercise more control over their fertility.

The United Nations estimated in mid-2019 that the human population will

reach about 9.7 billion by 2050, a downward revision from an older

projection to account for the fact that fertility has been falling

faster than previously thought in the developing world. The global

annual rate of growth has been declining steadily since the late

twentieth century, dropping to about one percent in 2019. In fact, by the late 2010s, 83 of the world's countries had sub-replacement fertility.

During the early to mid-2010s, more babies were born to Christian

mothers and those of any other religion in the world, reflecting the

fact that Christianity remained the most popular religion in existence.

However, it was the Muslims who had a faster rate of growth. About 33%

of the world's babies were born to Christians who made up 31% of the

global population between 2010 and 2015, compared to 31% to Muslims,

whose share of the human population was 24%. During the same period, the

religiously unaffiliated (including atheists and agnostics) made up 16%

of the population but gave birth to only 10% of the world's children.

Africa

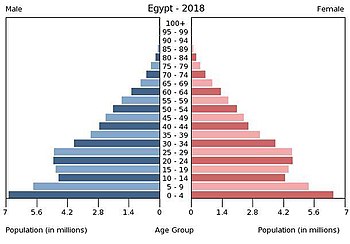

Population pyramid of Egypt in 2018

Egypt's population reached the 100-million milestone in February

2020. According to government figures, during the 1990s and 2000s,

Egypt's fertility rate fell from 5.2 down to 3.0, but then rose up to

3.5 in 2018, according to the United Nations. If the current rate of

growth continues, Egypt will be home to more than 128 million people by

2030. Such rapid population growth is a cause for concern in a country

marked by poverty, unemployment, shortages of clean water, lack of

affordable housing, and traffic congestion. Harsh geography exacerbates

the problem: 95% of the population lives on just 4% of the land, a

region in the neighborhood of the Nile River roughly half the size of

Ireland. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

claimed that overpopulation posed as much a threat to national security

as terrorism. He launched a campaign called “Two Is Enough” in order to

curb the problem, but to no avail. Egypt's fertility rate surged at

around the Arab Spring,

likely as a result of political chaos, economic uncertainty, and funds

for birth control from Western governments drying up. Fertility rates

remained the highest in rural areas, where children are considered a

blessing, but the impact is most visible in Greater Cairo,

a megalopolis home to over 20 million people. In general, Egypt's

densely populated cities and towns have one million additional residents

each year between 2008 and 2018.

Statistical projections from the United Nations in 2019 suggest

that, by 2020, the people of Niger would have a median age of 15.2, Mali

16.3, Chad 16.6, Somalia, Uganda, and Angola all 16.7, the Democratic

Republic of the Congo 17.0, Burundi 17.3, Mozambique and Zambia both

17.6. (This means that more than half of their populations were born in

the first two decades of the twenty-first century.) These are the

world's youngest countries by median age. While a booming population can

induce substantial economic growth, if healthcare, education, and

economic needs were not met, there would be chronic youth unemployment,

low productivity, and social unrest. Investing in human capital is crucial.

While Africa is the world's most fertile region, it also has the world's highest child mortality rates. Nevertheless, Africa is largely responsible for human population growth in the twenty-first century, overtaking Asia.

Moreover, sub-Saharan Africa is the only major region that is an

exception to the general trend of falling family size seen around the

world.

Asia

Population pyramid of China in 2018

In 2016, the Chinese Communist Party replaced one-child policy

with the two-child policy; the nation's birth rate briefly surged

before continuing on a downward path. In 2019, 14.65 million babies were

born in China, the lowest since 1961. Although demographers and

economists have urged the Chinese Central Government to eliminate all

birth restrictions, they have been reluctant to do so. Economist Ren

Zeping of Evergrande calculated that between 2013 and 2028, the number

of Chinese women between the ages of 20 and 35 would drop by 30%.

Official data is often unreliable and even self-contradictory. "China’s

birth numbers are very sloppy and highly influenced by politics,"

demographer Yi Fuxian of the University of Wisconsin – Madison told the South China Morning Post. Overall, China's population grew to 1.4 billion in 2019 from 1.39 billion the year before. Less than 6% of China's population was under five years old in 2018, compared to 3.85% in Japan.[10]

A Chinese person born in the late 2010s has a life expectancy of 76

years, up from 44 in 1960. According to a projection by the United

Nations, China's median age would reach that of the United States in

2020 and would subsequently converge with Europe's but would remain

below that of Japan. If the current trend continues, by 2050, the median

age of China will be 50, compared to 42 for the United States and 38

for India.

Such a trend has fueled predictions of dreadful socioeconomic problems. A study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

(CASS) published in January 2020 predicts that China's population would

peak in 2029 at 1.44 billion, after which decline would be

"unstoppable." CASS calculated that China's population will fall to 1.36

billion by mid-century, losing almost 200 million workers. CASS

recommended that the government implement policies that would address

the problems of a shrinking labor force and an increasing elderly

population, which means a growing dependency rate.

A large and young labor force and domestic consumption have driven

China's rapid economic growth. Yet due a shrinking pool of young people,

China has suffered from labor shortages and reduced growth in the

2010s. Young Chinese women living in the twenty-first century tend to be

reluctant to have children for a number of reasons. In large cities,

such as Shanghai, people typically spend at least a third of their

income on raising a child. Chinese women have become a lot more

career-oriented. On top of that, Chinese work places generally to not

offer accommodations for women with young children, who often face

demotion or even unemployment after returning from maternity leave.

As a result of cultural ideals, government policy, and modern

medicine, there has been severe gender imbalances in China and India.

According to the United Nations, in 2018, China and India had a combined

50 million of excess males under the age of 20. Such a discrepancy

fuels loneliness epidemics, human trafficking (from elsewhere in Asia,

such as Cambodia and Vietnam), and prostitution, among other societal

problems.

Population pyramid of Singapore in 2018

Singapore's total fertility rate continues to decline in the 2010s,

as more and more young people are choosing to delay or eschew marriage

and parenthood. It reached 1.14 in 2018, making it the lowest since 2010

and one of the lowest in the world.

Reasons for this include long work hours, digital disruption,

uncertainties surrounding global trade, climate change, high cost of

living, and long wait times for public housing.

The median age for first-time mothers rose from 29.7 in 2009 to 30.6 in

2018, which poses a problem because fertility declines with age.

Meanwhile, the death rate has been increasing since 1998; Singapore now

faces an aging population.

In fact, Singapore's birth rate has been below the replacement level of

2.1 since the 1980s, and appears to be stabilizing by during the first

two decades of the twenty-first century. Government incentives such as

the baby bonus have proven insufficient to raise the birth rate.

The number of women in their prime childbearing years (25–29) who

remained single increased from 60.9% in 2007 to 68.1% in 2017. For men,

the corresponding numbers were 77.5% and 80.7%, respectively. In

Singapore, the singleness rate is a major determinant of fertility

because only 10% of married couples have no children at all. While it is

not unusual for men to marry late because they are expected to have

established themselves before getting married and to be the primary

breadwinner, one major reason why women are marrying later is because

higher education eliminates the need to get married for economic

survival.

At the 2019 Forbes Global CEO Conference, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong

said that one of the top issues facing his country is finding the right

demographic balance. "To secure our future, we must make our own

babies, enough of them. Because if all of the next generation are not

our own, then where do they come from and what is the point of this?" he

said. Lee added that the long-term goal of his government is to

maintain a workforce that is two-thirds Singaporean, with the rest being

brought in from overseas. He argued that such a ratio is manageable

while relaxing immigration restriction would be "unwise" because "there

is no shortage of people who want to come."

Map of East Asia by total fertility rates in 2018

Population pyramid of South Korea in 2018

Singapore's experience mirrors those of Japan and South Korea.

A baby boom occurred in the aftermath of the Korean War, and the

government subsequently encouraged people to have no more than two

children per couple. As a result, South Korea's fertility has been

falling ever since.

South Korea's fertility rate dropped below 1.0 in 2018 for the first

time since that country began keeping statistics in 1970. The figure for

2017 was also a record low, at 1.05. Since 2005, the government has

spent a fortune on child subsidies and campaigns promoting reproduction

but without much success. Possible reasons for Korea's abysmal fertility

rate include the high cost of raising a child, high youth unemployment,

the burden of childcare on career-minded women, a stressful education

system, and high levels of competition in Korean society. In South

Korea, because marriage is usually associated with child-rearing, it is

extremely rare for children to be born out of wedlock. That figure stood

at 1.9% as of 2017. By contrast, in some other developed countries,

such as France and Norway, it is not uncommon for children to be born to

unmarried couples, at 55% or higher.

Government figures show that the average age of at first marriage for

women climbed from 24.8 in 1990 to 30.2 in 2018 while the age of first

birth was 31.6. According to Statistics Korea, women to give birth to

their first child in their early 30s are unlikely to have more than one.

In Korea's traditionalist society, new mothers face discrimination in

the work force, and as such delaying childbirth becomes commonplace.

Such a low fertility rate endangers the nation's welfare programs

(including healthcare and pensions), and causes more and more schools to

close. It also has implications for national security, as the South

Korean military relies on conscription to confront the North Korean

threat.

Population pyramid of Taiwan in 2018

According to the National Development Council of Taiwan

(NDC), the nation's population could start shrinking by 2022 and the

number of people of working age could fall 10% by 2027. About half of

Taiwanese would be aged 50 or over by 2034.

According to the NDC, Taiwan reached the stage of being an aging

society – one in which the number of people aged 65 and up is about 7% –

in 1993. Like South Korea, Taiwan has since moved from being an aging

society to an aged one, where the number of elderly people exceeds 14%.

It therefore takes the country just 25 years, compared to 17 for South

Korea. During the 2010s, Taiwan's fertility rate hovered just above 1.0,

making it one of the lowest in the world. In fact, data from the Ministry of the Interior shows it has consistently been below 1.5 since 2001.

(In 2010, Taiwan's fertility rate actually fell below 1.0 because it

was thought to be a bad year to have children because he previous year

was considered inauspicious for marriage.) Many couples still live with

their parents, and the older generation expects women to stay at home,

take care of children, and do house chores. Stipends and subsidies from the government have been unsuccessful in encouraging more people to reproduce, but the government has added more money for childcare, education, and birth subsidies. The government is also considering immigration policies that attract highly skilled workers from other countries, and to make English an official language.

At the current rate, Taiwan is set to transition from an aged to

super-aged society, where 21% of the population is over 65 years of age,

in eight years, compared to seven years for Singapore, eight years for

South Korea, 11 years for Japan, 14 for the United States, 29 for

France, and 51 for the United Kingdom. As of 2018, Japan was already a super-aged society, with 27% of its people being older than 65 years. According to government data, Japan's total fertility rate was 1.43 in 2017.

Population pyramid of Vietnam in 2018

Vietnam's population grew from 60 million in 1986 to 97 million in

2018, with the rate of growth falling to about one percent in the late

2010s. Like Bangladesh and unlike Egypt, Vietnam is a developing country

that has successfully curbed its population growth. Vietnam's median age in 2018 was 26 and rising. Between the 1970s and the late 2010s, life expectancy climbed from 60 to 76.

It is now the second highest in Southeast Asia. Vietnam's fertility

rate dropped from 5 in 1980 to 3.55 in 1990 and then to 1.95 in 2017. In

that same year, 23% of the Vietnamese population was 15 years of age or

younger, down from almost 40% in 1989. According to the World Health

Organization (WHO), Vietnam's population is one of the fastest aging in

the world. WHO projected that the proportion of people above the age of

65 would rise from 4% in 2017 to almost 7% by 2030. According to the

International Monetary Fund (IMF), "Vietnam is at risk of growing old before it grows rich." The share of working-age Vietnamese peaked in 2011, when the country's annual GDP per capita at purchasing power parity was $5,024, compared to $32,585 for South Korea, $31,718 for Japan, and $9,526 for China. Other rapidly growing Southeast Asian economies, such as the Philippines, saw similar demographic trends.

In India, the number of women who would like to have more than

one child has declined significantly. The National Family Health Survey

of 2018 found that only 24% of Indian women were interested in having a

second child, down from 68% a decade prior. Nine states – Kerala, Tamil

Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, West Bengal,

Punjab and Himachal Pradesh – found their fertility rate to be below the

replacement level in 2018. In general, India's falling fertility is

correlated with increasing women's literacy rates and level of

education, rising economic prosperity, improved mobility, and later

marriage.

Europe

In 2018, 19.7% of the population the European Union as a whole was at least 65 years old.

The median age of all 28 members of the bloc, including the United

Kingdom which recently decided to leave, was 43 years in 2019. It was

about 29 in the 1950s, when there were just six members: Belgium,

France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Like all other

inhabited continents, Europe saw significant population growth in the

late twentieth century. However, Europe's growth is projected to halt by

the early 2020s due to falling fertility rates and an aging population.

In 2015, a woman living in the European Union had on average 1.5

children, down from 2.6 in 1960. Although the E.U. continues to

experience a net influx of immigrants, this is not enough to balance out

the low fertility rates.

Population pyramid of Italy in 2018

Italy is a country where the problem of an aging population is

especially acute. The fertility rate dropped from about four in the

1960s down to 1.2 in the 2010s. This is not because young Italians do

not want to procreate. Quite the contrary, having a lot of children is

an Italian ideal. But its economy has been floundering since the Great

Recession of 2007–8, with the youth unemployment rate at a staggering

35% in 2019. Many Italians have moved abroad – 150,000 did in 2018 – and

many are young people pursuing educational and economic opportunities.

With the plunge in the number of births each year, the Italian

population is expected to decline in the next five years. The Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) reported that the number of babies born in 2018 in Italy was the lowest since the unification of Italy in 1861.

Moreover, the Baby Boomers are retiring in large numbers, and their

numbers eclipse those of the young people taking care of them. Only

Japan has an age structure more tilted towards the elderly. In 2018, 23% of the Italian population was above the age of 65, compared to 27% for Japan.

One possible solution to this problem is incentivizing reproduction, as

France has done, by investing in longer parental leaves, daycare, and

tax exemptions for parents. As of 2019, France has approximately the

same population as Italy but 65% more births.[38]

In 2015, Italy introduced a cash handout of €800 per couple per child.

This does not seem to have had an impact in the long run. People may

choose to have a child earlier, but ultimately, this does not increase

the nation's fertility rate. This pattern has also been observed in

other countries, family study expert Anne Gauthier of the University of Groningen told the BBC. In Italy's case, the subsidy does not address economic concerns or social attitudes. Another solution is immigration, which has been alleviating the decline, but it does not come without political backlash.

Population pyramid of Greece in 2018

As a result of its financial crisis, Greece also suffers from a

serious demographic problem as many young people are leaving the country

in search of better opportunities elsewhere. Between 2009 and 2018,

about half a million people left the country, many of them of

child-bearing age. In 2010, 115,000 children were born; that number dropped to 92,000 in 2015, and then to below 89,000 in 2017, the lowest on record.

In 2019, the fertility rate fell to just 1.3 per woman, well below the

replacement level and one of the lowest in Europe. Some of the more

remote regions of Greece suffer from shortages of obstetricians and

gynecologists, many of whom have gone abroad, which deters would-be

parents. And there are primary school students who are the only child of

their village and whose parents are in their 40s. In general, the

Greeks are having children later and having fewer children in the 2010s

compared to the 1980s. This brain drain and a rapidly aging population could spell disaster for the country.

The Spanish National Institute of Statistics

reported that the number of babies born in Spain in 2018 was the lowest

since 1998 and a 40.7% drop compared to 2008. This is due to the fact

that there were fewer women of childbearing age in Spain than in the

past, and that modern Spaniards are having fewer children.

In Portugal, the fertility rate dropped to 1.3 in the late 2010s.

Across Southern Europe, about 20% of women born in the 1970s are

childless, a number not seen since the First World War. More and more

schools have been forced to close and many towns are becoming empty.

Southern Europe could become countries of old people by the late 2030s

(when people born in the early 2010s and mid-2020s come of age) if the

current trend continues.

Hungary's birth rate was about 1.48 in 2018. For the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban,

which favors "procreation over immigration," raising the national

fertility rate is a matter of "strategic importance." In December 2018,

the Hungarian government nationalized six fertility clinics and said it

would offer free in vitro fertilization

(IVF) treatment starting February 2020, though the details of who would

be eligible for this program remain unclear. Like other Eastern

European countries, Hungary faces a declining population not just due to

its low birth rate, now half of what it was in 1950, but also to

emigration to Western Europe. About one in every seven Hungarian

children was born outside Hungary in the 2010s.

Population pyramid of Russia in 2018

The United Nations Population Division projected that Russia, which

had a birth rate of 1.75 in 2018, would find its population drop from

143 million down to 132 million by 2050. Russia's population has been on the decline since the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Another reason for Russia's demographic decline is the nation's low

life expectancy for men, at only 64 years in 2015, or 15 years less than

that in Italy, Germany, or Sweden. This is due to a combination of

unusually high rates of alcoholism, smoking, untreated cancer,

tuberculosis, suicides, violence, and HIV/AIDS. Although previous attempts to raise the birth rate have failed, in 2018, President Vladimir Putin

proposed giving money to low-income families, first-time mothers,

families with many children, and the creation of more nurseries. This is

part of a massive spending package aimed at revitalizing the struggling

Russian economy.

Despite recent declines, France retains one of the highest birth

rates in Europe at 1.92 in 2017, according to the World Bank. While many

countries have introduced policies intended to incentivize people to

have more children, these might be counter-balanced by other policies,

such as taxes. In France, the Ministry of Families is solely responsible

for family and child benefits packages, which are more generous for

larger families.

Germany's fertility rate rose from 1.33 in 2006 to 1.57 in 2017,

moving the country away from Spain and Italy and closer to the E.U.

average. This is due to a few reasons. Older women were having children,

which caused the rate to increase slightly. New immigrants, who arrived

in Germany in great numbers in that decade, tend to have more children

than natives, though their children will likely assimilate into German

society and will have smaller families of their own than their parents

and grandparents. In West Germany, working mothers were once

stigmatized, but this is no longer the case in unified Germany. In the

late 2000s and early 2010s, the German federal government introduced

more generous parental leave, encouraged fathers to take (more) time

off, and increased the number of nurseries, to which the government

declared children over one year old were entitled to. Although the

supply of nurseries remained insufficient, the number of children

enrolled in them rose from 286,000 in 2006 to 762,000 in 2017.

Population pyramid of Sweden in 2018

In Sweden, generous pro-natalist policies contribute to the nation

having a birth rate of 1.9 in 2017, which was high compared to the rest

of Europe. Swedish parents are entitled to 480 days of parental leave to

share between both parents, with fathers claiming on average 30% of the

amount. According to the European Commission, Sweden has one of the

lowest child poverty rates in the E.U. Nevertheless, Sweden's birth rate

has begun to fall in the late 2010s.

One of the reasons why Sweden has maintained a relatively high birth

rate is because the country has for decades been accepting immigrants,

who tend to have more children than the average Swede. But immigration

has proven to be a contentious issue. While some see it as a lifeline,

others view it as a threat.

Other Nordic countries face the same situation. Denmark, Norway,

Finland, and Iceland all saw their fertility rates decline in the late

2010s to between 1.49 and 1.71 from previously near replacement level,

although their economies had already recovered from the Great Recession

by that time. "The number of childless individuals is growing rapidly,

and the number of women having three or more children is going down.

This kind of fall is unheard of in modern times in Finland," family

sociologist Anna Rotkirch told AFP. According to Statistics Finland, the total fertility rate of that country in 2019 was 1.35, the lowest on record.

Causes for this decline include financial uncertainty, urbanization,

rising unemployment, declining median income, and high cost of living.

Falling fertility rates jeopardize the much prized Nordic welfare

systems. Generous parental benefits, including subsidized childcare, have proven ineffective in halting the demographic decline.

According to a 2020 report from Nordic Council of Ministers, the Finns

were aging at a faster rate than any of their counterparts in the Nordic

region.

Statistics Finland predicted in 2019 that given current trends in

fertility and migration, Finland's population would begin to decline by

2031.

Population pyramid of the Faroe Islands in 2018

According to the World Bank, the Faroe Islands

had a birth rate of about 2.5 in 2018, one of the highest in Europe, a

position they have maintained for decades. Like the rest of the Nordic

region, the territory has implemented a variety of family-friendly

policies, such as 46 weeks of parental leave, numerous and cheap

kindergartens, and tax cuts, including one for seven-seat vehicles. But

unlike the rest of the Nordic region, traditional family values and

family ties remain strong. Sociologist Hans Pauli Strøm of Statistics Faroe Islands

told the AFP, "In our culture, we perceive a person more as a member of

a family than as an independent individual. This close and intimate

contact between generations makes it easier to have children." In

addition, women's workforce participation is comparatively high, at 82%,

compared to an average of 59% for the European Union, of which the

Islands are not a member. More than half of Faroese women work part-time

as a matter of personal choice rather than labor-market conditions. The

autonomous Danish territory in the North Atlantic in fact had a

prosperous economy, as of the 2010s.

In 2018–19, the Republic of Ireland had the highest birth rate and the lowest death rate in the European Union, according to Eurostat.

Although Ireland had a thriving economy in the mid- to late-2010s, only

61,016 babies were born here in 2018 down from 75,554 in 2009.

Ireland's birth rate fell from 16.8 in 2008 to 12.6 in 2018, a drop of

about a quarter. The average age of first-time mothers in Ireland was

32.9 in 2018, up by over two years compared to the mid-2000s. Between

2006 and 2016, the number of babies born to women in their 40s doubled

while that to teenagers fell by 52.8%. Economist Edgar Morgenroth of Dublin City University told the Irish Times

that one of the reasons behind Ireland's falling fertility rate was the

fact that Ireland had a baby burst in the 1980s after a baby boom in

the 1970s, and the people born in the 1980s were starting families in

the 2010s. He further explained that high housing and childcare costs

could be behind Irish couples' reluctance. The marriage rate was 4.3 per

1,000 in 2018, the lowest since 1997 even though same-sex marriages

were included. In addition, people were getting married later. In 2018,

the average age at first marriage for a man was 36.4, up from 33.6 in

2008; for a women, those figures were 34.4 and 31.7, respectively.

Usually, rising birth and marriage rates correspond to a healthy

economy, but the present statistics seem to have buckled that trend.

As of 2016, Ireland was, demographically, a young country by European

standards. However, the country is aging quite quickly. According to the

Central Statistics Office,

although Ireland had more people below the age of 14 than above the age

of 65 in 2016, the situation could flip by 2031 in all projected

scenarios, which will pose a problem for public policy. For instance,

Ireland's healthcare system, already operating on a tight budget, will

be under even more pressure.

Population pyramid of the United Kingdom in 2018

According to the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics,

the fertility rates of England and Wales fell to a record low in 2018.

Moreover, they fell for women of all age groups except those in their

40s. A grand total of 657,076 children were born in England and Wales in

2018, down 10% from 2012. There were 11.1 births per a thousand people

in 2018, compared to a peak of 20.5 in 1947, and the total fertility

rate was 1.70, down from 1.76 in 2017. In fact, their fertility rates

have been consistently below replacement since the late 1970s. At the

same time, the number of stillbirths – when a baby is born after at

least 24 weeks of pregnancy but with no signs of life – plummeted to a

record low for the second consecutive year, standing at 4.1 per a

thousand births in 2018. England said it was committed to pushing that

number down to 2.6 by 2025.

Falling fertility rates in England and Wales have been part of a

continuing trend since the late twentieth century, with 1977 and

1992-2002 the only years where these jurisdictions had lower fertility

rates on record. As has been the case since the start of the new

millennium, the birth rate of women below the age of 20 continues to

fall, down to 11.9 in 2018. Before 2004, women in their mid- to late-20s

had the highest fertility rate, but between the mid-2000s and the

late-2010s, those in their early- to mid-30s held that position. Social

statistician and demographer Ann Berrington of the University of Southampton told The Guardian

that access to education, "changing aspirations" in life, the

availability of emergency and long-acting contraception, and the lack of

affordable housing were among the reasons behind the decline in

fertility among people in their 20s and 30s. Meanwhile, in Scotland, the fertility rate continues its downward trend since 2008. Figures from the National Records of Scotland

(NRS) reveal that 12,580 births were registered in the final quarter of

2018. Except for 2002, this is the lowest since record-keeping began in

1855. NRS explained that economic insecurity and the postponement of

motherhood, which often means having fewer children, are among the

reasons why. In the late 2010s, 46% of U.K. couples had only one child.

North America

Population pyramid of Canada in 2018

In Canada, about one in five Millennials were delaying having

children because of financial worries. Canada's average non-mortgage

debt was CAN$20,000 in 2018. One in three Millennials felt "overwhelmed"

by their liabilities, compared to 26% of Generation X and 13% of Baby

Boomers, according to consultant firm BDO Canada. More than one in three

Canadians with children felt stressed out by debt, compared with one

fifth of those without children. Many Canadian couples in their 20s and

30s are also struggling with their student loan debts. Research by the Royal Bank of Canada

suggests that Canadian Millennials have been flocking to the large

cities in spite of their expensive costs of living between the mid- and

late 2010s in search of economic opportunities and cultural amenities. Data from Statistics Canada

reveals that between 2000 and 2017, the birth rate among women under 30

years old fell in all provinces and territories except New Brunswick

women between the ages of 25 and 29 whereas that of women of age 30 and

over rose everywhere except in Nunavut among women aged 35 to 39.

Meanwhile, the adolescent fertility rate (15 to 19) halved in most of

Canada, a result likely due to improved sex education. The comparatively

low birth rate of women in their 20s living in British Columbia and

Ontario was correlated with the high housing costs in these provinces.

On the other hand, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut had relatively

high fertility rates because they have large Indigenous populations, and

Indigenous women tend to have more children. (Data for Yukon was not

available.)

During the early 2010s, among the various religious groups in

Canada, Muslims had the highest fertility rate of all. At 2.4 per woman,

they outpaced Hindus (2.0) Sikhs (1.9), Jews (1.8), Christians (1.6),

and secular people (1.4). Nationwide, 38.6% of Canadian couples had only one child during the late 2010s.

Population pyramid of the United States in 2018

As their economic prospects improve, most American Millennials say they desire marriage, children, and home ownership. While Millennials were initially responsible for the so-called "back-to-the-city" trend, by the late 2010s, Millennial homeowners were more likely to be in the suburbs than the cities.

Besides the cost of living, including housing costs, people are leaving

the big cities in search of warmer climates, lower taxes, better

economic opportunities, and better school districts for their children.

According to the Pew Research Center, by 2016, the cumulative number of

American women of the millennial generation who had given birth at

least once reached 17.3 million. About 1.2 million Millennial women had

their first child that year. By the mid-2010s, Millennials, who made up

29% of the adult population and 35% of the workforce of the U.S., were

responsible for a majority of births in the nation. In 2016, 48% of

Millennial women were mothers, compared to 57% of Generation-X women in

2000 when they were the same age. The increasing age of women when they

become mothers for the first time is a trend that can be traced back to

the 1970s, if not earlier.

Factors behind this trend include a declining interest in marriage, the

growth in educational attainment, and the rise of women's participation

in the workforce. Single-child families were the fastest growing type of family units in the U.S. during the late 2010s.

A report from the Brookings Institution

stated that in the United States, the Millennials are a bridge between

the largely Caucasian pre-Millennials (Generation X and their

predecessors) and the more diverse post-Millennials (Generation Z and

their successors).

Overall, the number of births to Caucasian women in the United States

dropped 7% between 2000 and 2018. Among foreign-born Caucasian women,

however, the number of births increased by 1% in the same period.

Although the number of births to foreign-born Hispanic women fell from

58% in 2000 to 50% in 2018, the share of births due to U.S.-born

Hispanic women increased from 20% in 2000 to 24% in 2018. The number of

births to foreign-born Asian women rose from 19% in 2000 to 24% in 2018

while that due to U.S.-born Asian women went from 1% in 2000 to 2% in

2018. In all, between 2000 and 2017, more births were to foreign-born

than U.S.-born women.

By analyzing data from the Census Bureau, the Pew Research Center

discovered that in 2017, at least 20% of kindergartners in public

schools were Hispanics in a grand total of 18 U.S. states plus the

District of Columbia, compared to only eight states in 2000 and 17 in

2010. Between 2010 and 2017, Massachusetts and Nebraska joined the list

while Idaho left. This reflects the falling pace of population growth of

Hispanics in the United States, due to declining fertility and

immigration rates. Hispanics, who comprised 18% of the U.S. population

(or about 60 million people) have been spreading across the United

States since the 1980s and are now the largest minority ethnic group in

the nation. They also made up 28% of the students in K-12 public schools

in 2019, up from 14% in 1995. For comparison, the number of Asian

public-school students increased slightly, from 4% to 6% during the same

period. Blacks fell slightly from 17% to 15%, and whites dropped from

65% to 47%. Overall, the number of children born to ethnic minorities

has exceeded 50% of the total since 2015.

Provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

reveal that U.S. fertility rates have fallen below the replacement

level of 2.1 since 1971. In 2017, it dropped to 1.765, the lowest in

three decades. 15.4% of the U.S. population was over 65 years of age in 2018.

After the Second World War, the U.S. fertility rate peaked in 1958 at

3.77 births per woman, fell to 1.84 in 1980, and climbed to 2.08 in 1990

before declining again in 2007.

However, there is great variation in terms of geography, age groups,

and ethnicity. South Dakota had the highest birth rate at 2,228 per a

thousand women and the District of Columbia the lowest at 1,421. Besides

South Dakota, only Utah (2,121) had a birth rate above replacement

level.

From 2006 to 2016, women whose ages range from the mid-20s to the

mid-30s maintained the highest birth rates of all while those in their

late 30s and early 40s saw significant increases in birth rates. American women are having children later in life, with the average age at first birth rising to 26.4 in the late 2010s, up from 23 in the mid-1990s. Falling teenage birth rates play a role in this development.

In fact, the number of births given by teenagers, which reached ominous

levels in the 1990s, have plummeted by about 60% between 2006 and 2016.

This is thanks in no small part to the collapse of birth rates among

black and Hispanic teens, down 50% from 2006. Overall, births fell for Asians, blacks, Hispanics, and whites but remained stable for native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

While Hispanic American women still maintained the highest fertility

rate of any racial or ethnic groups in the United States, their birth

rate dropped 31% between 2007 and 2017. Like their American peers and

unlike their immigrant parents and grandparents, young Hispanic American

women in the 2010s were more focused on their education and careers and

less interested in having children.

That U.S. fertility rates continue to drop is anomalous to

demographers because fertility rates typically track the nation's

economic health. It was no surprise that U.S. fertility rates dropped

during the Great Recession of 2007–8. But the U.S. economy has shown

strong signs of recovery for some time, and birthrates continue to fall.

In general, however, American women still tend to have children earlier

than their counterparts from other developed countries and the U.S.

total fertility rate remains comparatively high for a rich country. In fact, compared with their counterparts from other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),

first-time American mothers were among the youngest on average, on par

with Latvian women (26.5 years) during the 2010s. At the other extreme

end were women from Italy (30.8), and South Korea (31.4). During the

same period, American women ended their childbearing years with more

children on average (2.2) than most other developed countries, with the

notable exception of Icelandic women (2.3). At the other end were women

from Germany, Italy, Spain, and Japan (all 1.5).

Below-replacement-level fertility rates could lead to labor

shortages in the future. Speaking to the Associated Press, family

specialist Karen Benjamin Guzzo from Bowling Green State University

in Ohio recommended childcare subsidies, preschool expansion, (paid)

parental leave, housing assistance, and student debt reduction or

forgiveness.

Oceania

Population pyramid of Australia in 2018

Australia's total fertility rate has fallen from above three in the

post-war era, to about replacement level (2.1) in the 1970s to below

that in the late 2010s. It stood at 1.74 in 2017. However, immigration

has been offsetting the effects of a declining birthrate. In the 2010s,

among the residents of Australia, 5% were born in the United Kingdom,

2.5% from China, 2.2% from India, and 1.1% from the Philippines. 84% of

new arrivals in the fiscal year of 2016 were below 40 years of age,

compared to 54% of those already in the country. Like other

immigrant-friendly countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and

the United States, Australia's working-age population is expected to

grow till about 2025. However, the ratio of people of working age to

dependents and retirees (the dependency ratio)

has gone from eight in the 1970s to about four in the 2010s. It could

drop to two by the 2060s, depending in immigration levels.

"The older the population is, the more people are on welfare benefits,

we need more health care, and there's a smaller base to pay the taxes,"

Ian Harper of the Melbourne Business School told ABC News (Australia).

While the government has scaled back plans to increase the retirement

age, to cut pensions, and to raise taxes due to public opposition,

demographic pressures continue to mount as the buffering effects of

immigration are fading away.

Australians coming of age in the early twenty-first century are more

reluctant to have children compared to their predecessors due to

economic reasons: higher student debt, expensive housing, and negative

income growth.

Statistics New Zealand

reported that the nation's fertility rate in 2017 was 1.81, the lowest

on record. Although the total number of births went up, the birth rate

went down because of country's larger population thanks to high levels

of immigration. New Zealand's fertility rate remained more or less

stable between the late 1970s and the late 2010s. Younger women were

driving the birth rate down, with those between the ages of 15 and 29

having the lowest birth rates on record. In 2017, New Zealand teenagers

had one half the number of babies of 2008, and under a quarter of 1972.

Meanwhile, women above the age of 30 were having more children. Between

the late 2000s and late 2010s, an average of 60,308 babies were born in

New Zealand.

Education

Asia

In order to boost the nation's birthrate, in 2019, the government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

introduced a number of education reforms. Starting October 2019,

preschool education will be free for all children between the ages of

three and five. Childcare will be free for children under the age of two

from low-income households. These programs will be funded by a

consumption tax hike, from eight to ten percent. Starting April 2020,

entrance and tuition fees for public as well as private universities

will be waived or reduced. Students from low-income and tax-exempt

families will be eligible for financial assistance to help them cover

textbook, transportation, and living expenses. The whole program is

projected to cost ¥776 billion (US$7.1 billion) per annum.

Europe

In France, while year-long mandatory military service for men was abolished in 1996 by President Jacques Chirac, who wanted to build a professional all-volunteer military, all citizens between 17 and 25 years of age must still participate in the Defense and Citizenship Day, when they are introduced to the French Armed Forces, and take language tests. In 2019, President Emmanuel Macron

introduced something similar to mandatory military service, but for

teenagers, as promised during his presidential campaign. Known as the Service National Universel

or SNU, it is a compulsory civic service. While students will not have

to shave their heads or handle military equipment, they will have to

sleep in tents, get up early (at 6:30 am), participate in various

physical activities, raise the tricolor, and sing the national anthem.

They will have to wear a uniform, though it is more akin to the outfit

of security guards rather than military personnel. This program takes a

total of four weeks. In the first two, youths learn how to provide first

aid, how navigating with a map, how to recognize fake news, emergency

responses for various scenarios, and self-defense. In addition, they get

health checks and get tested on their mastery of the French language,

and they participate in debates on a variety of social issues, including

environmentalism, state secularism, and gender equality. In the second

fortnight, they volunteer with a charity for local government. The aim

of this program is to promote national cohesion and patriotism, at a

time of deep division on religious and political grounds, to get people

out of their neighborhoods and regions, and mix people of different

socioeconomic classes, something mandatory military service used to do.

Supporters thought that teenagers rarely raise the national flag, spend

too much time on their phones, and felt nostalgic for the era of

compulsory military service, considered a rite of passage for young men

and a tool of character-building. Critics argued that this program is

inadequate, and would cost too much.

The SNU is projected to affect some 800,000 French citizens each year

when it becomes mandatory for all aged 16 to 21 by 2026, at a cost of

some €1.6 billion.

Another major concern is that it will overburden the French military,

already stretched thin by counter-terrorism campaigns at home and

abroad.

A 2015 IFOP poll revealed that 80% of the French people supported some

kind of mandatory service, military, or civilian. At the same time,

returning to conscription was also popular; supporters included 90% of

the UMP party, 89% of the National Front (now the National Rally), 71% of the Socialist Party, and 67% of people aged 18 to 24. This poll was conducted after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks.

North America

The American Academy of Pediatricians recommended that parents allow their children more time to play.

In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics

released a policy statement summarizing progress on developmental and

neurological research on unstructured time spent by children,

colloquially 'play', and noting the importance of playtime for social,

cognitive, and language skills development. This is because to many

educators and parents, play has come to be seen as outdated and

irrelevant.

In fact, between 1981 and 1997, time spent by children on unstructured

activities dropped by 25% due to increased amounts of time spent on

structured activities. Unstructured time tended to be spent on screens

at the expense of active play.

The statement encourages parents and children to spend more time on

"playful learning," which reinforces the intrinsic motivation to learn

and discover and strengthens the bond between children and their parents

and other caregivers. It also helps children handle stress and prevents

"toxic stress,"

something that hampers development. Dr. Michael Yogman, the lead author

of the statement, noted that play does not necessarily have to involve

fancy toys; common household items would do as well. Moreover, parents

reading to children also counts as play, because it encourages children

to use their imaginations.

In 2019, psychiatrists from Quebec launched a campaign urging for

the creation of courses on mental health for primary schoolchildren in

order to teach them how to handle a personal or social crisis, and to

deal with the psychological impact of the digital world. According to

the Association des médecins psychiatres du Québec (AMPQ), this campaign

focuses on children born after 2010, that is, Generation Alpha. In

addition to the AMPQ, this movement is backed by the Fédération des

médecins spécialistes du Québec (FMSQ), the Quebec Pediatric Association

(APQ), the Association des spécialistes en médecine préventive du

Québec (ASMPQ) and the Fondation Jeunes en Tête.

Although the Common Core standards, an education initiative in the United States, eliminated the requirement that public elementary schools teach cursive writing

in 2010, lawmakers from many states, including Illinois, Ohio, and

Texas, have introduced legislation to teach it in theirs in 2019.

Some studies point to the benefits of handwriting – print or cursive –

for the development of cognitive and motor skills as well as memory and

comprehension. For example, one 2012 neuroscience study suggests that

handwriting "may facilitate reading acquisition in young children."

Cursive writing has been used to help students with learning

disabilities, such as dyslexia, a disorder that makes it difficult to

interpret words, letters, and other symbols. Unfortunately, lawmakers often cite them out of context, conflating handwriting in general with cursive handwriting. In any case, some 80% of historical records and documents of the United States, such as the correspondence of Abraham Lincoln, was written by hand in cursive, and students today tend to be unable to read them.

Historically, cursive writing was regarded as a mandatory, almost

military, exercise. But today, it is thought of as an art form by those

who pursue it, both adults and children.

In 2013, less than a third of American public schools had access to broadband Internet service, according to the non-profit EducationSuperHighway. By 2019, however, that number reached 99%. This has increased the frequency of digital learning.

Since the early 2010s, a number of U.S. states have taken steps

to strengthen teacher education. Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas had the top

programs in 2014. Meanwhile, Rhode Island, which previously had the

nation's lowest bar on who can train to become a school teacher, has

been admitting education students with higher and higher average SAT, ACT, and GRE

scores. The state aims to accept only those with standardized test

scores in the top third of the national distribution by 2020, which

would put it in the ranks of education superpowers such as Finland and Singapore. In Finland, studying to become a teacher is as tough and prestigious as studying to become a medical doctor or a lawyer.

Health problems

Food allergies

While food allergies have been observed by doctors since ancient times and virtually all foods can be allergens, research by the Mayo Clinic

in Minnesota found they are becoming increasingly common since the

early 2000s. Today, one in twelve American children has a food allergy,

with peanut allergy being the most prevalent type. Reasons for this

remain poorly understood.

Nut allergies in general have quadrupled and shellfish allergies have

increased 40% between 2004 and 2019. In all, about 36% of American

children have some kind of allergy. By comparison, this number among the

Amish in Indiana is 7%. Allergies have also risen ominously in other

Western countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, the number of

children hospitalized for allergic reactions increased by a factor of

five between 1990 and the late 2010s, as did the number of British

children allergic to peanuts. In general, the better developed the

country, the higher the rates of allergies. Reasons for this also remain poorly understood. One possible explanation, supported by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases,

is that parents keep their children "too clean for their own good."

They recommend exposing newborn babies to a variety of potentially

allergenic foods, such as peanut butter, before they reach the age of

six months. According to this "hygiene hypothesis," such exposures give

the infant's immune system some exercise, making it less likely to

overreact. Evidence for this includes the fact that children living on a

farm are consistently less likely to be allergic than their

counterparts who are raised in the city, and that children born in a

developed country to parents who immigrated from developing nations are

more likely to be allergic than their parents are.

Problems arising from screen time

Anatomical diagram of myopia or nearsightedness.

A 2015 study found that the frequency of nearsightedness

has doubled in the United Kingdom within the last 50 years.

Ophthalmologist Steve Schallhorn, chairman of the Optical Express

International Medical Advisory Board, noted that researchers have

pointed to a link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices

and eyestrain. The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm on a similar vein. According to a spokeswoman, digital eyestrain, or computer vision syndrome,

is "rampant, especially as we move toward smaller devices and the

prominence of devices increase in our everyday lives." Symptoms include

dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty

focusing, headaches. However, the syndrome does not cause vision loss or

any other permanent damage. In order to alleviate or prevent eyestrain,

the Vision Council

recommends that people limit screen time, take frequent breaks, adjust

the screen brightness, change the background from bright colors to gray,

increase text sizes, and blinking more often. The Council advises

parents to limit their children's screen time as well as lead by example

by reducing their own screen time in front of children.

In 2019, the World Health Organization

(WHO) issued recommendations on the amount young children should spend

in front of a screen every day. WHO said toddlers under the age of five

should spend no more than an hour watching a screen and infants under

the age of one should not be watching at all. Its guidelines are similar

to those introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which

recommended that children under 19 months old should not spend time

watching anything other than video chats. Moreover, it said children

under two years old should only watch "high-quality programming" under

parental supervision. However, Andrew Przybylski, who directs research

at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford, told the

Associated Press that "Not all screen time is created equal" and that

screen time advice needs to take into account "the content and context

of use." In addition, the United Kingdom's Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

said its available data was not strong enough to indicate the necessity

of screen time limits. WHO said its recommendations were intended to

address the problem of sedentary behavior leading to health issues such

as obesity.

Obesity and malnutrition

A report by the United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF)

released October 2019 stated that some 700 million children under the

age of five worldwide are either obese or undernourished. Although there

was a 40% drop in malnourishment in developing countries between 1990

and 2015, some 149 million toddlers are too short for their age, which

hampers body and brain development. UNICEF's nutrition program chief

Victor Aguayo said, "A mother who is overweight or obese can have

children who are stunted or wasted." About one in two youngsters suffer

from deficiencies of vitamins and minerals. Only two-fifths of infants

are exclusively breastfed, as recommended by pediatricians and

nutritionists, while the sale of formula milk jumped 40% globally. In

middle-income countries such as Brazil, China, and Turkey, that number

is 75%. Even though obesity was virtually non-existent in poor countries

three decades ago, today, at least ten percent of children in them

suffer from this condition. The report recommends taxes on sugary drinks

and beverages and enhanced regulatory oversight of breast milk

substitutes and fast foods.

Use of electronic communications technology

Many members of Generation Alpha have grown up using smartphones and tablets as part of their childhood entertainment. Some of their parents used electronic gadgets and pacifiers simultaneously. Others even use portable digital devices as pacifiers. In addition, electronic devices are also used as educational aids.

As a matter of fact, their parents, the Millennials, are heavy social

media users. A 2014 report from cybersecurity firm AVG stated that 6% of

parents created a social media account and 8% an email account for

their baby or toddler. According to BabyCenter,

an online company specializing in pregnancy, childbirth, and

child-rearing, 79% of Millennial mothers used social media on a daily

basis and 63% used their smartphones more frequently since becoming

pregnant or giving birth. More specifically, 24% logged on to Facebook more frequently and 33% did the same to Instagram after becoming a mother. Non-profit advocacy group Common Sense Media

warned that parents should take better care of their online privacy,

lest their and their children's personal information and photographs

fall into the wrong hands. This warning was issued after a Utah mother

reportedly found a photograph of her children on a social media post

with pornographic hashtags in May 2015.

Being born into an environment where the use of electronic devices is

ubiquitous comes with its own challenges: cyber-bullying, screen

addiction, and inappropriate contents. Nevertheless, because the

Millennials are themselves no stranger to this environment, they can use

their personal experience to help their children navigate it.

Predictions

A yawning infant (2018)

The first wave of Generation Alpha will reach adulthood by the 2030s.

By that time, the human population is expected to be just under nine

billion, and the world will have the highest proportion of people over

60 years of age in history, meaning this demographic cohort will bear the burden of an aging population.

According to Mark McCrindle, a social researcher from Australia,

Generation Alpha will most likely delay standard life markers such as

marriage, childbirth, and retirements, as did the few previous

generations. McCrindle estimated that Generation Alpha will make up 11%

of the global workforce by 2030.

He also predicted that they will live longer and have smaller families,

and will be "the most formally educated generation ever, the most

technology-supplied generation ever, and globally the wealthiest

generation ever."

Writing in 2009, demographer Phillip Longman

predicted that falling fertility rates around the world, among

developed and even some developing countries, and the resultant

demographic changes will play a role in the ongoing cultural evolution.

Governments have not and will not be able to dramatically increase

fertility rates; they succeed only in helping people have children

earlier. In many current countries, various cultural and economic

realities discourage procreation. Longman observed that in the past

there have been cases of jurisdictions finding their fertility rates to

be too low, yet humanity has obviously not gone extinct. The kingdoms

and empires of old and the people who forged them are no more, but those

places remain populated—just with different people. When certain groups

of people have no children or too few, they will gradually be replaced

by those who have more children. People who live in fast-moving and

cosmopolitan societies typically find their connections to their ancestors fade

and are thus less likely to have children whereas those who will

eventually outnumber them tend to be religious, to hold traditional

views, and to identify strongly with their own people and country.

Longman contended that already by the early 2000s it had become apparent

that the mainstream culture of the United States was gradually shifting

away from secular individualism and towards religious fundamentalism while Europeans were slowly distancing themselves from the European Union and being "world citizens."

Longman asserted that another consequence of low fertility is the

increasing difficulty of financing welfare programs, such as pension

schemes and elderly care, ordinary family functions that had been

appropriated by the state. This is because while life expectancy has

grown only slightly in recent decades, fertility has fallen

dramatically, meaning the widening dependency ratio is largely due to

the fact that many of the taxpayers needed to finance these programs

were never even born. Raising taxes would depress fertility rates even

further. As a result, they will have to be scaled back or even abolished

and family units that are less dependent on government will become more

common as these now enjoy an evolutionary advantage. Longman also

predicted that single-child households would find their number dwindle

as a percentage of the population because one child can only replace one

parent, not both, and the descendants of families with many children

will slowly become a majority and will retain the values that made such

families possible. Of course, history contains cases of major youth

revolts, with the 1960s being a recent example. But back in the post-war

era, it was the norm for people to marry and have many children, with

very little difference along social, political or religious lines. In

the early twenty-first century, families with just one or no children

have become a lot more common, meaning the future proponents of

counterculture would likely find that their companions will have never

existed.

In his 2010 book, Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth? Demography and Politics in the Twenty-First Century, political and religious demographer Eric Kaufmann

argued that the answer to the question raised in the title is in the

affirmative because demographic realities pose real challenges to the

assumption of the inevitability of secular and liberal progress. He

observed that devout factions tend to have a significant fertility

advantage over their more moderate counterparts and the non-religious.

For instance, white Catholic women in France have on average half a

child more than their white secular counterparts while the Amish in the

United States have three to four times more children than their fellow

Christians on average. Highly religious groups tend to isolate

themselves from the secularizing effects of modern mainstream Western

society, making it more likely that the children will retain their

parents' faiths. At the same time, secular people generally have rather

low fertility rates by comparison for a variety of reasons, such as

materialism, individualism, the preference for the here and now,

feminism, environmentalism, or general pessimism. Kaufmann projected

that secularism will have a mixed future in Europe. It will remain

strong in most Catholic countries, notably Ireland and Spain, but has

essentially ground to a halt in Protestant Europe and in France, and

will falter in Northwestern Europe by mid-century. He told Mercator Net

that the only way to buckle the trend involves "a creed that touches the

emotional registers can lure away the children of fundamentalists" and

"a repudiation of multiculturalism." He suggested that "secular

nationalism" and moderate religion associated with the nation-state

could be part of the mix, but these traditions have been losing support

at a considerable rate.

A 2017 projection by the Pew Research Center suggests that

between 2015 and 2060, the human population would grow by about 32%.

Among the major religious groups, only Muslims (70%) and Christians

(34%) are above this threshold and as such would have a higher share of

the global population than they do now, especially Muslims. Hindus

(27%), Jews (15%), followers of traditional folk religions (5%), and the

religiously unaffiliated (3%) would grow in absolute numbers, but would

be in relative decline because their rates of growth are below the

global average. On the other hand, Buddhists would find their numbers

shrink by 7% during the same period. This is due to sub-replacement

fertility and population aging in Buddhist-majority countries such as

China, Japan, and Thailand. This projection has taken into account

religious switching. Moreover, previous research suggests that switching

plays only a minor role in the growth or decline of religion compared

to fertility and mortality.

Eric Kaufmann's Whiteshift is an extensive study of how the migration-driven demographic transformation of the West affects the ballot box.

The title of the 2018 book encodes Kaufmann's predictions that, as a

result of international migration, Western countries will become ever

more ethnically diverse and a growing number of people will be of mixed

heritage. He further argues that the category of 'white people' will be

enlarged to include more ethnically diverse individuals. For Kaufmann,

one of the major schisms in the political landscape of the West at the

time of writing is due to factions that want to speed up this process

and those who want to slow it down. He suggested that the surge of

nationalism and populism observed in many Western countries is due to

the latter group. For decades, the norms of acceptable political demands

had been established by the media, institutions of higher education,

and mainstream political groups. Such norms include what he called "left

modernism," a more precise term for what is commonly referred to as political correctness, and "asymmetrical multiculturalism,"

or the idea that all cultures present in a given society deserve to be

preserved except the host culture. These norms have prevented mainstream

politicians and political parties from responding to the concerns of

large swathes of the voting population, giving nationalist populists an

opportunity to rise to the front.

In a related book, National Populism – The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, political scientists Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin attempted to explain the political phenomenon of the same name using a '4D model': destruction of the national culture due to large-scale international migration; deprivation of opportunities due to globalization and in the post-industrial economy with its frequent disruptions and slow growth; growing distrust

by working-class and rural voters who feel increasingly alienated by

liberal cosmopolitan city-dwelling political and media elites; and de-alignment

from traditional allegiances, which can be seen in high levels of voter

volatility, or people switching from one party to another between

elections. National populism

should not be confused with left-wing populism, which focuses on

socioeconomic class rather than love of country. Eatwell and Goodwin

observed that support for mainstream social democratic parties all

across Europe has plummeted – in France and the Netherlands the

socialists got pushed to the fringe – and predicted that nationalism and

populism would remain a dominant characteristic of Western politics

until the other side can build a platform that resonates better with the

general public. Even after some surprising political developments such

as the 2016 United Kingdom European Union Membership Referendum

(Brexit), many mainstream politicians still believed their constituents

wanted more immigration, more deregulation, more globalization, and

more cultural diversity, when YouGov opinion polls of European voters

showed that their number one concern was immigration.