Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior." The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns matters of value, and thus comprises the branch of philosophy called axiology.

Ethics seeks to resolve questions of human morality by defining concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime. As a field of intellectual inquiry, moral philosophy also is related to the fields of moral psychology, descriptive ethics, and value theory.

Three major areas of study within ethics recognized today are:

- Meta-ethics, concerning the theoretical meaning and reference of moral propositions, and how their truth values (if any) can be determined

- Normative ethics, concerning the practical means of determining a moral course of action

- Applied ethics, concerning what a person is obligated (or permitted) to do in a specific situation or a particular domain of action.

Defining ethics

The English word "ethics" is derived from the Ancient Greek word ēthikós (ἠθικός), meaning "relating to one's character", which itself comes from the root word êthos (ἦθος) meaning "character, moral nature". This word was transferred into Latin as ethica and then into French as éthique, from which it was transferred into English.

Rushworth Kidder states that "standard definitions of ethics have typically included such phrases as 'the science of the ideal human character' or 'the science of moral duty'". Richard William Paul and Linda Elder

define ethics as "a set of concepts and principles that guide us in

determining what behavior helps or harms sentient creatures". The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy states that the word "ethics" is "commonly used interchangeably with 'morality' ... and sometimes it is used more narrowly to mean the moral principles of a particular tradition, group or individual."

Paul and Elder state that most people confuse ethics with behaving in

accordance with social conventions, religious beliefs and the law and

don't treat ethics as a stand-alone concept.

The word ethics in English refers to several things. It can refer to philosophical

ethics or moral philosophy—a project that attempts to use reason to

answer various kinds of ethical questions. As the English philosopher Bernard Williams

writes, attempting to explain moral philosophy: "What makes an inquiry a

philosophical one is reflective generality and a style of argument that

claims to be rationally persuasive." Williams describes the content of this area of inquiry as addressing the very broad question, "how one should live". Ethics can also refer to a common human ability to think about ethical problems that is not particular to philosophy. As bioethicist

Larry Churchill has written: "Ethics, understood as the capacity to

think critically about moral values and direct our actions in terms of

such values, is a generic human capacity." Ethics can also be used to describe a particular person's own idiosyncratic principles or habits. For example: "Joe has strange ethics."

Meta-ethics

Meta-ethics is the branch of philosophical ethics that asks how we

understand, know about, and what we mean when we talk about what is

right and what is wrong.

An ethical question pertaining to a particular practical situation—such

as, "Should I eat this particular piece of chocolate cake?"—cannot be a

meta-ethical question (rather, this is an applied ethical question). A

meta-ethical question is abstract and relates to a wide range of more

specific practical questions. For example, "Is it ever possible to have

secure knowledge of what is right and wrong?" is a meta-ethical

question.

Meta-ethics has always accompanied philosophical ethics. For

example, Aristotle implies that less precise knowledge is possible in

ethics than in other spheres of inquiry, and he regards ethical

knowledge as depending upon habit and acculturation in a way that makes it distinctive from other kinds of knowledge. Meta-ethics is also important in G.E. Moore's Principia Ethica from 1903. In it he first wrote about what he called the naturalistic fallacy. Moore was seen to reject naturalism in ethics, in his Open Question Argument. This made thinkers look again at second order questions about ethics. Earlier, the Scottish philosopher David Hume had put forward a similar view on the difference between facts and values.

Studies of how we know in ethics divide into cognitivism and non-cognitivism;

this is quite akin to the thing called descriptive and non-descriptive.

Non-cognitivism is the view that when we judge something as morally

right or wrong, this is neither true nor false. We may, for example, be

only expressing our emotional feelings about these things. Cognitivism can then be seen as the claim that when we talk about right and wrong, we are talking about matters of fact.

The ontology of ethics is about value-bearing

things or properties, i.e. the kind of things or stuff referred to by

ethical propositions. Non-descriptivists and non-cognitivists believe

that ethics does not need a specific ontology

since ethical propositions do not refer. This is known as an

anti-realist position. Realists, on the other hand, must explain what

kind of entities, properties or states are relevant for ethics, how they

have value, and why they guide and motivate our actions.

Moral skepticism

Moral skepticism (or moral scepticism) is a class of metaethical theories all members of which entail that no one has any moral knowledge. Many moral skeptics also make the stronger, modal claim that moral knowledge is impossible. Moral skepticism is particularly opposed to moral realism: the view that there are knowable and objective moral truths.

Some proponents of moral skepticism include Pyrrho, Aenesidemus, Sextus Empiricus, David Hume, Max Stirner, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Moral skepticism divides into three subclasses: moral error theory (or moral nihilism), epistemological moral skepticism, and noncognitivism. All three of these theories share the same conclusions, which are:

- (a) we are never justified in believing that moral claims (claims of the form "state of affairs x is good," "action y is morally obligatory," etc.) are true and, even more so

- (b) we never know that any moral claim is true.

However, each method arrives at (a) and (b) by different routes.

Moral error theory holds that we do not know that any moral claim is true because

- (i) all moral claims are false,

- (ii) we have reason to believe that all moral claims are false, and

- (iii) since we are not justified in believing any claim we have reason to deny, we are not justified in believing any moral claims.

Epistemological moral skepticism is a subclass of theory, the members of which include Pyrrhonian

moral skepticism and dogmatic moral skepticism. All members of

epistemological moral skepticism share two things: first, they

acknowledge that we are unjustified in believing any moral claim, and

second, they are agnostic on whether (i) is true (i.e. on whether all moral claims are false).

- Pyrrhonian moral skepticism holds that the reason we are unjustified in believing any moral claim is that it is irrational for us to believe either that any moral claim is true or that any moral claim is false. Thus, in addition to being agnostic on whether (i) is true, Pyrrhonian moral skepticism denies (ii).

- Dogmatic moral skepticism, on the other hand, affirms (ii) and cites (ii)'s truth as the reason we are unjustified in believing any moral claim.

Noncognitivism holds that we can never know that any moral claim is true because moral claims are incapable of being true or false (they are not truth-apt). Instead, moral claims are imperatives (e.g. "Don't steal babies!"), expressions of emotion (e.g. "stealing babies: Boo!"), or expressions of "pro-attitudes" ("I do not believe that babies should be stolen.")

Normative ethics

Normative

ethics is the study of ethical action. It is the branch of ethics that

investigates the set of questions that arise when considering how one

ought to act, morally speaking. Normative ethics is distinct from meta-ethics

because normative ethics examines standards for the rightness and

wrongness of actions, while meta-ethics studies the meaning of moral

language and the metaphysics of moral facts. Normative ethics is also distinct from descriptive ethics, as the latter is an empirical

investigation of people's moral beliefs. To put it another way,

descriptive ethics would be concerned with determining what proportion

of people believe that killing is always wrong, while normative ethics

is concerned with whether it is correct to hold such a belief. Hence,

normative ethics is sometimes called prescriptive, rather than

descriptive. However, on certain versions of the meta-ethical view

called moral realism, moral facts are both descriptive and prescriptive at the same time.

Traditionally, normative ethics (also known as moral theory) was

the study of what makes actions right and wrong. These theories offered

an overarching moral principle one could appeal to in resolving

difficult moral decisions.

At the turn of the 20th century, moral theories became more

complex and were no longer concerned solely with rightness and

wrongness, but were interested in many different kinds of moral status.

During the middle of the century, the study of normative ethics declined

as meta-ethics grew in prominence. This focus on meta-ethics was in

part caused by an intense linguistic focus in analytic philosophy and by the popularity of logical positivism.

Virtue ethics

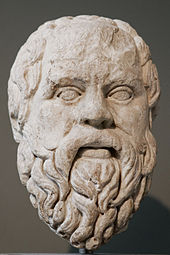

Virtue

ethics describes the character of a moral agent as a driving force for

ethical behavior, and it is used to describe the ethics of Socrates, Aristotle, and other early Greek philosophers. Socrates (469–399 BC) was one of the first Greek philosophers

to encourage both scholars and the common citizen to turn their

attention from the outside world to the condition of humankind. In this

view, knowledge bearing on human life was placed highest, while all other knowledge was secondary. Self-knowledge

was considered necessary for success and inherently an essential good. A

self-aware person will act completely within his capabilities to his

pinnacle, while an ignorant person will flounder and encounter

difficulty. To Socrates, a person must become aware of every fact (and

its context) relevant to his existence, if he wishes to attain

self-knowledge. He posited that people will naturally do what is good if

they know what is right. Evil or bad actions are the results of

ignorance. If a criminal was truly aware of the intellectual and

spiritual consequences of his or her actions, he or she would neither

commit nor even consider committing those actions. Any person who knows

what is truly right will automatically do it, according to Socrates.

While he correlated knowledge with virtue, he similarly equated virtue with joy. The truly wise man will know what is right, do what is good, and therefore be happy.

Aristotle

(384–323 BC) posited an ethical system that may be termed "virtuous".

In Aristotle's view, when a person acts in accordance with virtue this

person will do good and be content. Unhappiness and frustration are

caused by doing wrong, leading to failed goals and a poor life.

Therefore, it is imperative for people to act in accordance with virtue,

which is only attainable by the practice of the virtues in order to be

content and complete. Happiness was held to be the ultimate goal. All

other things, such as civic life or wealth,

were only made worthwhile and of benefit when employed in the practice

of the virtues. The practice of the virtues is the surest path to

happiness.

Aristotle asserted that the soul of man had three natures:

body (physical/metabolism), animal (emotional/appetite), and rational

(mental/conceptual). Physical nature can be assuaged through exercise

and care; emotional nature through indulgence of instinct and urges; and

mental nature through human reason and developed potential. Rational

development was considered the most important, as essential to

philosophical self-awareness and as uniquely human. Moderation was encouraged, with the extremes seen as degraded and immoral. For example, courage is the moderate virtue between the extremes of cowardice and recklessness.

Man should not simply live, but live well with conduct governed by

virtue. This is regarded as difficult, as virtue denotes doing the right

thing, in the right way, at the right time, for the right reason.

Stoicism

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus posited that the greatest good was contentment and serenity. Peace of mind, or apatheia, was of the highest value;

self-mastery over one's desires and emotions leads to spiritual peace.

The "unconquerable will" is central to this philosophy. The individual's

will should be independent and inviolate. Allowing a person to disturb

the mental equilibrium is, in essence, offering yourself in slavery. If a

person is free to anger you at will, you have no control over your

internal world, and therefore no freedom. Freedom from material

attachments is also necessary. If a thing breaks, the person should not

be upset, but realize it was a thing that could break. Similarly, if

someone should die, those close to them should hold to their serenity

because the loved one was made of flesh and blood destined to death.

Stoic philosophy says to accept things that cannot be changed, resigning

oneself to the existence and enduring in a rational fashion. Death is

not feared. People do not "lose" their life, but instead "return", for

they are returning to God (who initially gave what the person is as a

person). Epictetus said difficult problems in life should not be

avoided, but rather embraced. They are spiritual exercises needed for

the health of the spirit, just as physical exercise is required for the

health of the body. He also stated that sex and sexual desire are to be

avoided as the greatest threat to the integrity

and equilibrium of a man's mind. Abstinence is highly desirable.

Epictetus said remaining abstinent in the face of temptation was a

victory for which a man could be proud.

Contemporary virtue ethics

Modern virtue ethics was popularized during the late 20th century in large part as a response to G.E.M. Anscombe's "Modern Moral Philosophy". Anscombe argues that consequentialist and deontological ethics are only feasible as universal theories if the two schools ground themselves in divine law.

As a deeply devoted Christian herself, Anscombe proposed that either

those who do not give ethical credence to notions of divine law take up

virtue ethics, which does not necessitate universal laws as agents

themselves are investigated for virtue or vice and held up to "universal

standards", or that those who wish to be utilitarian or

consequentialist ground their theories in religious conviction. Alasdair MacIntyre, who wrote the book After Virtue,

was a key contributor and proponent of modern virtue ethics, although

some claim that MacIntyre supports a relativistic account of virtue

based on cultural norms, not objective standards. Martha Nussbaum,

a contemporary virtue ethicist, objects to MacIntyre's relativism,

among that of others, and responds to relativist objections to form an

objective account in her work "Non-Relative Virtues: An Aristotelian

Approach". However, Nussbaum's accusation of relativism appears to be a misreading. In Whose Justice, Whose Rationality?,

MacIntyre's ambition of taking a rational path beyond relativism was

quite clear when he stated "rival claims made by different traditions

[…] are to be evaluated […] without relativism" (p. 354) because indeed

"rational debate between and rational choice among rival traditions is

possible” (p. 352). Complete Conduct Principles for the 21st Century

blended the Eastern virtue ethics and the Western virtue ethics, with

some modifications to suit the 21st Century, and formed a part of

contemporary virtue ethics.

One major trend in contemporary virtue ethics is the Modern Stoicism movement.

Intuitive ethics

Ethical intuitionism (also called moral intuitionism) is a family of views in moral epistemology (and, on some definitions, metaphysics). At minimum, ethical intuitionism is the thesis that our intuitive awareness of value, or intuitive knowledge of evaluative facts, forms the foundation of our ethical knowledge.

The view is at its core a foundationalism

about moral knowledge: it is the view that some moral truths can be

known non-inferentially (i.e., known without one needing to infer them

from other truths one believes). Such an epistemological view implies

that there are moral beliefs with propositional contents; so it implies cognitivism. As such, ethical intuitionism is to be contrasted with coherentist approaches to moral epistemology, such as those that depend on reflective equilibrium.

Throughout the philosophical literature, the term "ethical

intuitionism" is frequently used with significant variation in its

sense. This article's focus on foundationalism reflects the core

commitments of contemporary self-identified ethical intuitionists.

Sufficiently broadly defined, ethical intuitionism can be taken to encompass cognitivist forms of moral sense theory. It is usually furthermore taken as essential to ethical intuitionism that there be self-evident or a priori moral knowledge; this counts against considering moral sense theory to be a species of intuitionism.

Ethical intuitionism was first clearly shown in use by the philosopher Francis Hutcheson. Later ethical intuitionists of influence and note include Henry Sidgwick, G.E. Moore, Harold Arthur Prichard, C.S. Lewis and, most influentially, Robert Audi.

Objections to ethical intuitionism include whether or not there

are objective moral values- an assumption which the ethical system is

based upon- the question of why many disagree over ethics if they are

absolute, and whether Occam's razor cancels such a theory out entirely.

Hedonism

Hedonism posits that the principal ethic is maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain.

There are several schools of Hedonist thought ranging from those

advocating the indulgence of even momentary desires to those teaching a

pursuit of spiritual bliss. In their consideration of consequences, they

range from those advocating self-gratification

regardless of the pain and expense to others, to those stating that the

most ethical pursuit maximizes pleasure and happiness for the most

people.

Cyrenaic hedonism

Founded by Aristippus of Cyrene, Cyrenaics

supported immediate gratification or pleasure. "Eat, drink and be

merry, for tomorrow we die." Even fleeting desires should be indulged,

for fear the opportunity should be forever lost. There was little to no

concern with the future, the present dominating in the pursuit of

immediate pleasure. Cyrenaic hedonism encouraged the pursuit of

enjoyment and indulgence without hesitation, believing pleasure to be

the only good.

Epicureanism

Epicurean ethics is a hedonist form of virtue ethics. Epicurus "...presented a sustained argument that pleasure, correctly understood, will coincide with virtue." He rejected the extremism of the Cyrenaics, believing some pleasures and indulgences to be detrimental to human beings. Epicureans

observed that indiscriminate indulgence sometimes resulted in negative

consequences. Some experiences were therefore rejected out of hand, and

some unpleasant experiences endured in the present to ensure a better

life in the future. To Epicurus, the summum bonum, or greatest

good, was prudence, exercised through moderation and caution. Excessive

indulgence can be destructive to pleasure and can even lead to pain. For

example, eating one food too often makes a person lose a taste for it.

Eating too much food at once leads to discomfort and ill-health. Pain

and fear were to be avoided. Living was essentially good, barring pain

and illness. Death was not to be feared. Fear was considered the source

of most unhappiness. Conquering the fear of death would naturally lead

to a happier life. Epicurus reasoned if there were an afterlife and

immortality, the fear of death was irrational. If there was no life

after death, then the person would not be alive to suffer, fear or

worry; he would be non-existent in death. It is irrational to fret over

circumstances that do not exist, such as one's state of death in the

absence of an afterlife.

State consequentialism

State consequentialism, also known as Mohist consequentialism,

is an ethical theory that evaluates the moral worth of an action based

on how much it contributes to the basic goods of a state. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

describes Mohist consequentialism, dating back to the 5th century BC,

as "a remarkably sophisticated version based on a plurality of intrinsic

goods taken as constitutive of human welfare".

Unlike utilitarianism, which views pleasure as a moral good, "the basic

goods in Mohist consequentialist thinking are ... order, material

wealth, and increase in population". During Mozi's

era, war and famines were common, and population growth was seen as a

moral necessity for a harmonious society. The "material wealth" of

Mohist consequentialism refers to basic needs

like shelter and clothing, and the "order" of Mohist consequentialism

refers to Mozi's stance against warfare and violence, which he viewed as

pointless and a threat to social stability.

Stanford sinologist David Shepherd Nivison, in The Cambridge History of Ancient China,

writes that the moral goods of Mohism "are interrelated: more basic

wealth, then more reproduction; more people, then more production and

wealth ... if people have plenty, they would be good, filial, kind, and

so on unproblematically."

The Mohists believed that morality is based on "promoting the benefit

of all under heaven and eliminating harm to all under heaven". In

contrast to Bentham's views, state consequentialism is not utilitarian

because it is not hedonistic or individualistic. The importance of

outcomes that are good for the community outweigh the importance of

individual pleasure and pain.

Consequentialism

Consequentialism refers to moral theories that hold the consequences

of a particular action form the basis for any valid moral judgment about

that action (or create a structure for judgment, see rule consequentialism).

Thus, from a consequentialist standpoint, a morally right action is one

that produces a good outcome, or consequence. This view is often

expressed as the aphorism "The ends justify the means".

The term "consequentialism" was coined by G.E.M. Anscombe in her essay "Modern Moral Philosophy" in 1958, to describe what she saw as the central error of certain moral theories, such as those propounded by Mill and Sidgwick. Since then, the term has become common in English-language ethical theory.

The defining feature of consequentialist moral theories is the

weight given to the consequences in evaluating the rightness and

wrongness of actions.

In consequentialist theories, the consequences of an action or rule

generally outweigh other considerations. Apart from this basic outline,

there is little else that can be unequivocally said about

consequentialism as such. However, there are some questions that many

consequentialist theories address:

- What sort of consequences count as good consequences?

- Who is the primary beneficiary of moral action?

- How are the consequences judged and who judges them?

One way to divide various consequentialisms is by the many types of

consequences that are taken to matter most, that is, which consequences

count as good states of affairs. According to utilitarianism,

a good action is one that results in an increase and positive effect,

and the best action is one that results in that effect for the greatest

number. Closely related is eudaimonic

consequentialism, according to which a full, flourishing life, which

may or may not be the same as enjoying a great deal of pleasure, is the

ultimate aim. Similarly, one might adopt an aesthetic consequentialism,

in which the ultimate aim is to produce beauty. However, one might fix

on non-psychological goods as the relevant effect. Thus, one might

pursue an increase in material equality or political liberty

instead of something like the more ephemeral "pleasure". Other theories

adopt a package of several goods, all to be promoted equally. Whether a

particular consequentialist theory focuses on a single good or many,

conflicts and tensions between different good states of affairs are to

be expected and must be adjudicated.

Utilitarianism

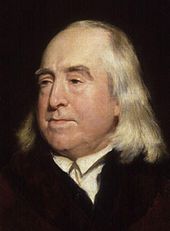

Jeremy Bentham

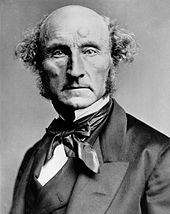

John Stuart Mill

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that argues the proper course of

action is one that maximizes a positive effect, such as "happiness",

"welfare", or the ability to live according to personal preferences. Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are influential proponents of this school of thought. In A Fragment on Government

Bentham says 'it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that

is the measure of right and wrong' and describes this as a fundamental axiom. In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation he talks of 'the principle of utility' but later prefers "the greatest happiness principle".

Utilitarianism is the paradigmatic example of a consequentialist

moral theory. This form of utilitarianism holds that the morally correct

action is the one that produces the best outcome for all people

affected by the action. John Stuart Mill,

in his exposition of utilitarianism, proposed a hierarchy of pleasures,

meaning that the pursuit of certain kinds of pleasure is more highly

valued than the pursuit of other pleasures. Other noteworthy proponents of utilitarianism are neuroscientist Sam Harris, author of The Moral Landscape, and moral philosopher Peter Singer, author of, amongst other works, Practical Ethics.

The major division within utilitarianism is between act utilitarianism and rule utilitarianism.

In act utilitarianism, the principle of utility applies directly to

each alternative act in a situation of choice. The right act is the one

that brings about the best results (or the least amount of bad results).

In rule utilitarianism, the principle of utility determines the

validity of rules of conduct (moral principles). A rule like

promise-keeping is established by looking at the consequences of a world

in which people break promises at will and a world in which promises

are binding. Right and wrong are the following or breaking of rules that

are sanctioned by their utilitarian value. A proposed "middle ground" between these two types is Two-level utilitarianism,

where rules are applied in ordinary circumstances, but with an

allowance to choose actions outside of such rules when unusual

situations call for it.

Deontology

Deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek δέον, deon, "obligation, duty"; and -λογία, -logia) is an approach to ethics that determines goodness or rightness from examining acts, or the rules and duties that the person doing the act strove to fulfill. This is in contrast to consequentialism,

in which rightness is based on the consequences of an act, and not the

act by itself. Under deontology, an act may be considered right even if

the act produces a bad consequence, if it follows the rule or moral law. According to the deontological view, people have a duty

to act in a way that does those things that are inherently good as acts

("truth-telling" for example), or follow an objectively obligatory rule

(as in rule utilitarianism).

Kantianism

Immanuel Kant's theory of ethics is considered deontological for several different reasons. First, Kant argues that to act in the morally right way, people must act from duty (Pflicht).

Second, Kant argued that it was not the consequences of actions that

make them right or wrong but the motives of the person who carries out

the action.

Kant's argument that to act in the morally right way one must act

purely from duty begins with an argument that the highest good must be

both good in itself and good without qualification. Something is "good in itself" when it is intrinsically good,

and "good without qualification", when the addition of that thing never

makes a situation ethically worse. Kant then argues that those things

that are usually thought to be good, such as intelligence, perseverance and pleasure,

fail to be either intrinsically good or good without qualification.

Pleasure, for example, appears not to be good without qualification,

because when people take pleasure in watching someone suffer, this seems

to make the situation ethically worse. He concludes that there is only

one thing that is truly good:

Nothing in the world—indeed nothing even beyond the world—can possibly be conceived which could be called good without qualification except a good will.

Kant

then argues that the consequences of an act of willing cannot be used

to determine that the person has a good will; good consequences could

arise by accident from an action that was motivated by a desire to cause

harm to an innocent person, and bad consequences could arise from an

action that was well-motivated. Instead, he claims, a person has a good

will when he 'acts out of respect for the moral law'. People 'act out of respect for the moral law' when they act in some way because

they have a duty to do so. So, the only thing that is truly good in

itself is a good will, and a good will is only good when the willer

chooses to do something because it is that person's duty, i.e. out of

"respect" for the law. He defines respect as "the concept of a worth

which thwarts my self-love".

Kant's three significant formulations of the categorical imperative are:

- Act only according to that maxim by which you can also will that it would become a universal law.

- Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.

- Every rational being must so act as if he were through his maxim always a legislating member in a universal kingdom of ends.

Kant argued that the only absolutely good

thing is a good will, and so the single determining factor of whether

an action is morally right is the will, or motive of the person doing

it. If they are acting on a bad maxim, e.g. "I will lie", then their

action is wrong, even if some good consequences come of it.

In his essay, On a Supposed Right to Lie Because of Philanthropic Concerns, arguing against the position of

Benjamin Constant, Des réactions politiques,

Kant states that "Hence a lie defined merely as an intentionally

untruthful declaration to another man does not require the additional

condition that it must do harm to another, as jurists require in their

definition (mendacium est falsiloquium in praeiudicium alterius).

For a lie always harms another; if not some human being, then it

nevertheless does harm to humanity in general, inasmuch as it vitiates

the very source of right [Rechtsquelle] ... All practical

principles of right must contain rigorous truth ... This is because such

exceptions would destroy the universality on account of which alone

they bear the name of principles."

Divine command theory

Although not all deontologists are religious, some believe in the

'divine command theory', which is actually a cluster of related theories

which essentially state that an action is right if God has decreed that

it is right. According to Ralph Cudworth, an English philosopher, William of Ockham, René Descartes, and eighteenth-century Calvinists all accepted various versions of this moral theory, as they all held that moral obligations arise from God's commands.

The Divine Command Theory is a form of deontology because, according to

it, the rightness of any action depends upon that action being

performed because it is a duty, not because of any good consequences

arising from that action. If God commands people not to work on Sabbath, then people act rightly if they do not work on Sabbath because God has commanded that they do not do so.

If they do not work on Sabbath because they are lazy, then their action

is not truly speaking "right", even though the actual physical action

performed is the same. If God commands not to covet a neighbour's goods,

this theory holds that it would be immoral to do so, even if coveting

provides the beneficial outcome of a drive to succeed or do well.

One thing that clearly distinguishes Kantian deontologism from

divine command deontology is that Kantianism maintains that man, as a

rational being, makes the moral law universal, whereas divine command

maintains that God makes the moral law universal.

Discourse ethics

Photograph of Jurgen Habermas, whose theory of discourse ethics was influenced by Kantian ethics

German philosopher Jürgen Habermas has proposed a theory of discourse ethics that he claims is a descendant of Kantian ethics.

He proposes that action should be based on communication between those

involved, in which their interests and intentions are discussed so they

can be understood by all. Rejecting any form of coercion or

manipulation, Habermas believes that agreement between the parties is

crucial for a moral decision to be reached. Like Kantian ethics, discourse ethics is a cognitive

ethical theory, in that it supposes that truth and falsity can be

attributed to ethical propositions. It also formulates a rule by which

ethical actions can be determined and proposes that ethical actions

should be universalisable, in a similar way to Kant's ethics.

Habermas argues that his ethical theory is an improvement on Kant's ethics. He rejects the dualistic framework of Kant's ethics. Kant distinguished between the phenomena world, which can be sensed and experienced by humans, and the noumena,

or spiritual world, which is inaccessible to humans. This dichotomy was

necessary for Kant because it could explain the autonomy of a human

agent: although a human is bound in the phenomenal world, their actions

are free in the intelligible world. For Habermas, morality arises from

discourse, which is made necessary by their rationality and needs,

rather than their freedom.

Pragmatic ethics

Associated with the pragmatists, Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and especially John Dewey,

pragmatic ethics holds that moral correctness evolves similarly to

scientific knowledge: socially over the course of many lifetimes. Thus,

we should prioritize social reform over attempts to account for

consequences, individual virtue or duty (although these may be

worthwhile attempts, if social reform is provided for).

Ethics of care

Care ethics contrasts with more well-known ethical models, such as

consequentialist theories (e.g. utilitarianism) and deontological

theories (e.g., Kantian ethics) in that it seeks to incorporate

traditionally feminized virtues and values that—proponents of care

ethics contend—are absent in such traditional models of ethics. These

values include the importance of empathetic relationships and

compassion.

Care-focused feminism is a branch of feminist thought, informed primarily by ethics of care as developed by Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings.

This body of theory is critical of how caring is socially assigned to

women, and consequently devalued. They write, “Care-focused feminists

regard women’s capacity for care as a human strength,” that should be

taught to and expected of men as well as women. Noddings proposes that

ethical caring has the potential to be a more concrete evaluative model

of moral dilemma than an ethic of justice. Noddings’ care-focused feminism requires practical application of relational ethics, predicated on an ethic of care.

Role ethics

Role ethics is an ethical theory based on family roles. Unlike virtue ethics, role ethics is not individualistic. Morality is derived from a person's relationship with their community. Confucian ethics is an example of role ethics though this is not straightforwardly uncontested. Confucian roles center around the concept of filial piety or xiao, a respect for family members. According to Roger T. Ames

and Henry Rosemont, "Confucian normativity is defined by living one's

family roles to maximum effect." Morality is determined through a

person's fulfillment of a role, such as that of a parent or a child.

Confucian roles are not rational, and originate through the xin, or human emotions.

Anarchist ethics

Anarchist

ethics is an ethical theory based on the studies of anarchist thinkers.

The biggest contributor to the anarchist ethics is the Russian

zoologist, geographer, economist, and political activist Peter Kropotkin.

Starting from the premise that the goal of ethical philosophy

should be to help humans adapt and thrive in evolutionary terms,

Kropotkin's ethical framework uses biology and anthropology as a basis –

in order to scientifically establish what will best enable a given

social order to thrive biologically and socially – and advocates certain

behavioural practices to enhance humanity's capacity for freedom and

well-being, namely practices which emphasise solidarity, equality, and

justice.

Kropotkin argues that ethics itself is evolutionary, and is inherited as

a sort of a social instinct through cultural history, and by so, he

rejects any religious and transcendental explanation of morality. The

origin of ethical feeling in both animals and humans can be found, he

claims, in the natural fact of "sociality" (mutualistic symbiosis),

which humans can then combine with the instinct for justice (i.e.

equality) and then with the practice of reason to construct a

non-supernatural and anarchistic system of ethics. Kropotkin suggests that the principle of equality at the core of anarchism is the same as the Golden rule:

This principle of treating others as one wishes to be treated oneself, what is it but the very same principle as equality, the fundamental principle of anarchism? And how can any one manage to believe himself an anarchist unless he practices it? We do not wish to be ruled. And by this very fact, do we not declare that we ourselves wish to rule nobody? We do not wish to be deceived, we wish always to be told nothing but the truth. And by this very fact, do we not declare that we ourselves do not wish to deceive anybody, that we promise to always tell the truth, nothing but the truth, the whole truth? We do not wish to have the fruits of our labor stolen from us. And by that very fact, do we not declare that we respect the fruits of others' labor? By what right indeed can we demand that we should be treated in one fashion, reserving it to ourselves to treat others in a fashion entirely different? Our sense of equality revolts at such an idea.

Postmodern ethics

The 20th century saw a remarkable expansion and evolution of critical theory, following on earlier Marxist Theory efforts to locate individuals within larger structural frameworks of ideology and action.

Antihumanists such as Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault and structuralists such as Roland Barthes

challenged the possibilities of individual agency and the coherence of

the notion of the 'individual' itself. This was on the basis that

personal identity was, in the most part, a social construction. As

critical theory developed in the later 20th century, post-structuralism sought to problematize human relationships to knowledge and 'objective' reality. Jacques Derrida

argued that access to meaning and the 'real' was always deferred, and

sought to demonstrate via recourse to the linguistic realm that "there

is no outside-text/non-text" ("il n'y a pas de hors-texte" is often mistranslated as "there is nothing outside the text"); at the same time, Jean Baudrillard

theorised that signs and symbols or simulacra mask reality (and

eventually the absence of reality itself), particularly in the consumer

world.

Post-structuralism and postmodernism

argue that ethics must study the complex and relational conditions of

actions. A simple alignment of ideas of right and particular acts is

not possible. There will always be an ethical remainder that cannot be

taken into account or often even recognized. Such theorists find

narrative (or, following Nietzsche and Foucault, genealogy)

to be a helpful tool for understanding ethics because narrative is

always about particular lived experiences in all their complexity rather

than the assignment of an idea or norm to separate and individual

actions.

Zygmunt Bauman says postmodernity

is best described as modernity without illusion, the illusion being the

belief that humanity can be repaired by some ethic principle.

Postmodernity can be seen in this light as accepting the messy nature of

humanity as unchangeable.

David Couzens Hoy states that Emmanuel Levinas's writings on the face of the Other and Derrida's

meditations on the relevance of death to ethics are signs of the

"ethical turn" in Continental philosophy that occurred in the 1980s and

1990s. Hoy describes post-critique ethics as the "obligations that

present themselves as necessarily to be fulfilled but are neither forced

on one or are enforceable" (2004, p. 103).

Hoy's post-critique model uses the term ethical resistance.

Examples of this would be an individual's resistance to consumerism in a

retreat to a simpler but perhaps harder lifestyle, or an individual's

resistance to a terminal illness. Hoy describes Levinas's account as

"not the attempt to use power against itself, or to mobilize sectors of

the population to exert their political power; the ethical resistance is

instead the resistance of the powerless"(2004, p. 8).

Hoy concludes that

The ethical resistance of the powerless others to our capacity to exert power over them is therefore what imposes unenforceable obligations on us. The obligations are unenforceable precisely because of the other's lack of power. That actions are at once obligatory and at the same time unenforceable is what put them in the category of the ethical. Obligations that were enforced would, by the virtue of the force behind them, not be freely undertaken and would not be in the realm of the ethical. (2004, p. 184)

Applied ethics

Applied ethics is a discipline of philosophy that attempts to apply

ethical theory to real-life situations. The discipline has many

specialized fields, such as engineering ethics, bioethics, geoethics, public service ethics and business ethics.

Specific questions

Applied ethics is used in some aspects of determining public policy, as well as by individuals facing difficult decisions. The sort of questions addressed by applied ethics include: “Is getting an abortion immoral?”; "Is euthanasia immoral?"; "Is affirmative action right or wrong?"; "What are human rights, and how do we determine them?"; "Do animals have rights as well?"; and "Do individuals have the right of self-determination?"

A more specific question could be: "If someone else can make

better out of his/her life than I can, is it then moral to sacrifice

myself for them if needed?" Without these questions, there is no clear

fulcrum on which to balance law, politics, and the practice of

arbitration—in fact, no common assumptions of all participants—so the

ability to formulate the questions are prior to rights balancing. But

not all questions studied in applied ethics concern public policy. For

example, making ethical judgments regarding questions such as, "Is lying

always wrong?" and, "If not, when is it permissible?" is prior to any

etiquette.

People, in general, are more comfortable with dichotomies (two

opposites). However, in ethics, the issues are most often multifaceted

and the best-proposed actions address many different areas concurrently.

In ethical decisions, the answer is almost never a "yes or no" or a

“right or wrong" statement. Many buttons are pushed so that the overall

condition is improved and not to the benefit of any particular faction.

And it has not only been shown that people consider the character

of the moral agent (i.e. a principle implied in virtue ethics), the

deed of the action (i.e. a principle implied in deontology),

and the consequences of the action (i.e. a principle implied in

utilitarianism) when formulating moral judgments, but moreover that the

effect of each of these three components depends on the value of each

component.

Particular fields of application

Bioethics

Bioethics is the study of controversial ethics brought about by advances in biology and medicine. Bioethicists are concerned with the ethical questions that arise in the relationships among life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, politics, law, and philosophy. It also includes the study of the more commonplace questions of values ("the ethics of the ordinary") that arise in primary care and other branches of medicine.

Bioethics also needs to address emerging biotechnologies that

affect basic biology and future humans. These developments include cloning, gene therapy, human genetic engineering, astroethics and life in space,

and manipulation of basic biology through altered DNA, RNA and

proteins, e.g. "three parent baby, where baby is born from genetically

modified embryos, would have DNA from a mother, a father and from a

female donor. Correspondingly, new bioethics also need to address life at its core. For example, biotic ethics value organic gene/protein life itself and seek to propagate it. With such life-centered principles, ethics may secure a cosmological future for life.

Business ethics

Business ethics (also corporate ethics) is a form of applied ethics or professional ethics that examines ethical principles and moral or ethical problems that arise in a business environment, including fields like medical ethics.

Business ethics represents the practices that any individual or group

exhibits within an organization that can negatively or positively affect

the businesses core values. It applies to all aspects of business

conduct and is relevant to the conduct of individuals and entire

organizations.

Business ethics has both normative

and descriptive dimensions. As a corporate practice and a career

specialization, the field is primarily normative. Academics attempting

to understand business behavior employ descriptive methods. The range

and quantity of business ethical issues reflect the interaction of

profit-maximizing behavior with non-economic concerns. Interest in

business ethics accelerated dramatically during the 1980s and 1990s,

both within major corporations and within academia. For example, today

most major corporations promote their commitment to non-economic values

under headings such as ethics codes and social responsibility charters.

Adam Smith said, "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even

for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy

against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."

Governments use laws and regulations to point business behavior in what

they perceive to be beneficial directions. Ethics implicitly regulates

areas and details of behavior that lie beyond governmental control.

The emergence of large corporations with limited relationships and

sensitivity to the communities in which they operate accelerated the

development of formal ethics regimes.

Business ethics also relates to unethical activities of

interorganizational relationships, such as strategic alliances,

buyer-supplier relationships, or joint ventures. Such unethical practices include, for instance, opportunistic behaviors, contract violations, and deceitful practices.

Machine ethics

In Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right from Wrong, Wendell Wallach and Colin Allen conclude that issues in machine ethics

will likely drive advancement in understanding of human ethics by

forcing us to address gaps in modern normative theory and by providing a

platform for experimental investigation.

The effort to actually program a machine or artificial agent to behave

as though instilled with a sense of ethics requires new specificity in

our normative theories, especially regarding aspects customarily

considered common-sense. For example, machines, unlike humans, can

support a wide selection of learning algorithms,

and controversy has arisen over the relative ethical merits of these

options. This may reopen classic debates of normative ethics framed in

new (highly technical) terms.

Military ethics

Military ethics are concerned with questions regarding the

application of force and the ethos of the soldier and are often

understood as applied professional ethics. Just war theory

is generally seen to set the background terms of military ethics.

However individual countries and traditions have different fields of

attention.

Military ethics involves multiple subareas, including the following among others:

- what, if any, should be the laws of war.

- justification for the initiation of military force.

- decisions about who may be targeted in warfare.

- decisions on choice of weaponry, and what collateral effects such weaponry may have.

- standards for handling military prisoners.

- methods of dealing with violations of the laws of war.

Political ethics

Political ethics (also known as political morality or public ethics)

is the practice of making moral judgements about political action and

political agents.

Public sector ethics

Public sector ethics is a set of principles that guide public

officials in their service to their constituents, including their

decision-making on behalf of their constituents. Fundamental to the

concept of public sector ethics is the notion that decisions and actions

are based on what best serves the public's interests, as opposed to the

official's personal interests (including financial interests) or

self-serving political interests.

Publication ethics

Publication

ethics is the set of principles that guide the writing and publishing

process for all professional publications. To follow these principles,

authors must verify that the publication does not contain plagiarism or publication bias.

As a way to avoid misconduct in research these principles can also

apply to experiments that are referenced or analyzed in publications by

ensuring the data is recorded honestly and accurately.

Plagiarism is the failure to give credit to another author's work or ideas, when it is used in the publication. It is the obligation of the editor of the journal to ensure the article does not contain any plagiarism before it is published.

If a publication that has already been published is proven to contain

plagiarism, the editor of the journal can retract the article.

Publication bias occurs when the publication is one-sided or "prejudiced against results".

In best practice, an author should try to include information from all

parties involved, or affected by the topic. If an author is prejudiced

against certain results, than it can "lead to erroneous conclusions

being drawn".

Misconduct in research can occur when an experimenter falsifies results.

Falsely recorded information occurs when the researcher "fakes"

information or data, which was not used when conducting the actual

experiment.

By faking the data, the researcher can alter the results from the

experiment to better fit the hypothesis they originally predicted. When

conducting medical research, it is important to honor the healthcare

rights of a patient by protecting their anonymity in the publication.

Respect for autonomy is the principle that decision-making should

allow individuals to be autonomous; they should be able to make

decisions that apply to their own lives. This means that individuals

should have control of their lives.

Justice is the principle that decision-makers must focus on

actions that are fair to those affected. Ethical decisions need to be

consistent with the ethical theory. There are cases where the management

has made decisions that seem to be unfair to the employees,

shareholders, and other stakeholders (Solomon, 1992, pp49). Such

decisions are unethical.

Relational ethics

Relational ethics are related to an ethics of care.

They are used in qualitative research, especially ethnography and

autoethnography. Researchers who employ relational ethics value and

respect the connection between themselves and the people they study, and

"...between researchers and the communities in which they live and

work." (Ellis, 2007, p. 4).

Relational ethics also help researchers understand difficult issues

such as conducting research on intimate others that have died and

developing friendships with their participants. Relational ethics in close personal relationships form a central concept of contextual therapy.

Animal ethics

Animal ethics is a term used in academia to describe human-animal

relationships and how animals ought to be treated. The subject matter

includes animal rights, animal welfare, animal law, speciesism, animal cognition, wildlife conservation, the moral status of nonhuman animals, the concept of nonhuman personhood, human exceptionalism, the history of animal use, and theories of justice.

Moral psychology

Moral psychology is a field of study that began as an issue in philosophy and that is now properly considered part of the discipline of psychology. Some use the term "moral psychology" relatively narrowly to refer to the study of moral development. However, others tend to use the term more broadly to include any topics at the intersection of ethics and psychology (and philosophy of mind). Such topics are ones that involve the mind and are relevant to moral issues. Some of the main topics of the field are moral responsibility, moral development, moral character (especially as related to virtue ethics), altruism, psychological egoism, moral luck, and moral disagreement.

Evolutionary ethics

Evolutionary ethics concerns approaches to ethics (morality) based on

the role of evolution in shaping human psychology and behavior. Such

approaches may be based in scientific fields such as evolutionary psychology or sociobiology, with a focus on understanding and explaining observed ethical preferences and choices.

Descriptive ethics

Descriptive ethics is on the less philosophical end of the spectrum

since it seeks to gather particular information about how people live

and draw general conclusions based on observed patterns. Abstract and

theoretical questions that are more clearly philosophical—such as, "Is

ethical knowledge possible?"—are not central to descriptive ethics.

Descriptive ethics offers a value-free approach to ethics, which defines it as a social science rather than a humanity. Its examination of ethics doesn't start with a preconceived theory but rather investigates observations of actual choices made by moral agents in practice. Some philosophers rely on descriptive ethics and choices made and unchallenged by a society or culture to derive categories, which typically vary by context. This can lead to situational ethics and situated ethics. These philosophers often view aesthetics, etiquette, and arbitration

as more fundamental, percolating "bottom up" to imply the existence of,

rather than explicitly prescribe, theories of value or of conduct. The

study of descriptive ethics may include examinations of the following:

- Ethical codes applied by various groups. Some consider aesthetics itself the basis of ethics—and a personal moral core developed through art and storytelling as very influential in one's later ethical choices.

- Informal theories of etiquette that tend to be less rigorous and more situational. Some consider etiquette a simple negative ethics, i.e., where can one evade an uncomfortable truth without doing wrong? One notable advocate of this view is Judith Martin ("Miss Manners"). According to this view, ethics is more a summary of common sense social decisions.

- Practices in arbitration and law, e.g., the claim that ethics itself is a matter of balancing "right versus right", i.e., putting priorities on two things that are both right, but that must be traded off carefully in each situation.

- Observed choices made by ordinary people, without expert aid or advice, who vote, buy, and decide what is worth valuing. This is a major concern of sociology, political science, and economics.