From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Allen Ginsberg | |

|---|---|

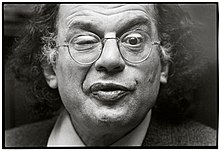

Allen Ginsberg in 1979

|

|

| Born | Irwin Allen Ginsberg June 3, 1926 Newark, New Jersey, United States |

| Died | April 5, 1997 (aged 70) New York City, United States |

| Occupation | Writer, poet |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Montclair State College, Columbia University |

| Literary movement | Beat literature, Hippie |

| Notable awards | National Book Award {1974} Robert Frost Medal (1986) |

| Partner | Peter Orlovsky 1954–1997 (Ginsberg's death) |

| Signature | |

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (/ˈɡɪnzbərɡ/; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and one of the leading figures of both the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the counterculture that soon would follow. He vigorously opposed militarism, economic materialism and sexual repression. Ginsberg is best known for his epic poem "Howl", in which he denounced what he saw as the destructive forces of capitalism and conformity in the United States.[1][2][3]

In 1957, "Howl" attracted widespread publicity when it became the subject of an obscenity trial, as it depicted heterosexual and homosexual sex[4] at a time when sodomy laws made homosexual acts a crime in every U.S. state. "Howl" reflected Ginsberg's own homosexuality and his relationships with a number of men, including Peter Orlovsky, his lifelong partner.[5] Judge Clayton W. Horn ruled that "Howl" was not obscene, adding, "Would there be any freedom of press or speech if one must reduce his vocabulary to vapid innocuous euphemisms?"[6]

Ginsberg was a practicing Buddhist who studied Eastern religious disciplines extensively. He lived modestly, buying his clothing in second-hand stores and residing in downscale apartments in New York’s East Village.[7] One of his most influential teachers was the Tibetan Buddhist, the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa, founder of the Naropa Institute, now Naropa University at Boulder, Colorado.[8] At Trungpa's urging, Ginsberg and poet Anne Waldman started The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics there in 1974.[9]

Ginsberg took part in decades of non-violent political protest against everything from the Vietnam War to the War on Drugs.[10] His poem "September on Jessore Road," calling attention to the plight of Bangladeshi refugees, exemplifies what the literary critic Helen Vendler described as Ginsberg's tireless persistence in protesting against "imperial politics, and persecution of the powerless."[11]

His collection The Fall of America shared the annual U.S. National Book Award for Poetry in 1974.[12] In 1979 he received the National Arts Club gold medal and was inducted into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.[13] In 1986 he was awarded the Golden Wreath of the Struga Poetry Evenings in Struga, Macedonia.[14] Ginsberg was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 1995 for his book Cosmopolitan Greetings: Poems 1986–1992.[15]

Biography

Early life and family

Ginsberg was born into a Jewish[16] family in Newark, New Jersey, and grew up in nearby Paterson.[17]As a young teenager, Ginsberg began to write letters to The New York Times about political issues, such as World War II and workers' rights.[18] While in high school, Ginsberg began reading Walt Whitman, inspired by his teacher's passionate reading.[19]

In 1943, Ginsberg graduated from Eastside High School and briefly attended Montclair State College before entering Columbia University on a scholarship from the Young Men's Hebrew Association of Paterson.[20] In 1945, he joined the Merchant Marines to earn money to continue his education at Columbia.[21] While at Columbia, Ginsberg contributed to the Columbia Review literary journal, the Jester humor magazine, won the Woodberry Poetry Prize and served as president of the Philolexian Society, the campus literary and debate group.[19] Ginsberg has stated that he considered the required freshman seminar to be his favorite course while at Columbia University. Its subject was The Great Books and was taught by Lionel Trilling.[22]

According to The Poetry Foundation Ginsberg spent several months in a mental institution after he pled insanity during a hearing. He was allegedly being prosecuted for harboring stolen goods in his dorm room. It was noted that the stolen property was not his. It belonged to an acquaintance.[23]

Relationship with his parents

His father Louis Ginsberg was a published poet and a high school teacher.[20][24] Ginsberg's mother, Naomi Livergant Ginsberg, was affected by a psychological illness that was never properly diagnosed.[25] She was also an active member of the Communist Party and took Ginsberg and his brother Eugene to party meetings. Ginsberg later said that his mother "made up bedtime stories that all went something like: 'The good king rode forth from his castle, saw the suffering workers and healed them.'"[18] Ginsberg criticized his father. "My father would go around the house," he once said, "either reciting Emily Dickinson and Longfellow under his breath or attacking T. S. Eliot for ruining poetry with his 'obscurantism.' I grew suspicious of both sides."[17]Naomi Ginsberg's mental illness often manifested as paranoid delusions. She would claim, for example, that the president had implanted listening devices in their home and that Louis' mother was trying to kill her.[26][27] Her suspicion of those around her caused Naomi to draw closer to young Allen, "her little pet," as Bill Morgan says in his biography of Ginsberg, titled, I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg.[28] She also tried to kill herself by slitting her wrists and was soon taken to Greystone, a mental hospital; she would spend much of Ginsberg's youth in mental hospitals.[29][30] His experiences with his mother and her mental illness were a major inspiration for his two major works, "Howl" and his long autobiographical poem "Kaddish for Naomi Ginsberg (1894–1956)".[31]

When he was in junior high school, he accompanied his mother by bus to her therapist. The trip deeply disturbed Ginsberg – he mentioned it and other moments from his childhood in "Kaddish".[25] His experiences with his mother's mental illness and her institutionalization are also frequently referred to in "Howl". For example, "Pilgrim State, Rockland, and Grey Stone's foetid halls" is a reference to institutions frequented by his mother and Carl Solomon, ostensibly the subject of the poem: Pilgrim State Hospital and Rockland State Hospital in New York and Greystone State Hospital in New Jersey.[30][32][33] This is followed soon by the line "with mother finally ******." Ginsberg later admitted the deletion was the expletive "fucked."[34] He also says of Solomon in section three, "I'm with you in Rockland where you imitate the shade of my mother," once again showing the association between Solomon and his mother.[35]

Ginsberg received a letter from his mother after her death responding to a copy of "Howl" he had sent her. It admonished Ginsberg to be good and stay away from drugs; she says, "The key is in the window, the key is in the sunlight at the window – I have the key – Get married Allen don't take drugs – the key is in the bars, in the sunlight in the window".[36] In a letter she wrote to Ginsberg's brother Eugene, she said, "God's informers come to my bed, and God himself I saw in the sky. The sunshine showed too, a key on the side of the window for me to get out. The yellow of the sunshine, also showed the key on the side of the window."[37] These letters and the inability to perform the kaddish ceremony inspired Ginsberg to write "Kaddish" which makes references to many details from Naomi's life, Ginsberg's experiences with her, and the letter, including the lines "the key is in the light" and "the key is in the window".[38]

New York Beats

In Ginsberg's freshman year at Columbia he met fellow undergraduate Lucien Carr, who introduced him to a number of future Beat writers, including Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and John Clellon Holmes. They bonded because they saw in one another an excitement about the potential of American youth, a potential that existed outside the strict conformist confines of post–World War II, McCarthy-era America.[39] Ginsberg and Carr talked excitedly about a "New Vision" (a phrase adapted from Yeats' "A Vision"), for literature and America. Carr also introduced Ginsberg to Neal Cassady, for whom Ginsberg had a long infatuation.[40] In the first chapter of his 1957 novel On the Road Kerouac described the meeting between Ginsberg and Cassady.[25] Kerouac saw them as the dark (Ginsberg) and light (Cassady) side of their "New Vision", a perception stemming partly from Ginsberg's association with communism, of which Kerouac had become increasingly distrustful. Though Ginsberg was never a member of the Communist Party, Kerouac named him "Carlo Marx" in On the Road. This was a source of strain in their relationship.[19]Also, in New York, Ginsberg met Gregory Corso in the Pony Stable Bar. Corso, recently released from prison, was supported by the Pony Stable patrons and was writing poetry there the night of their meeting. Ginsberg claims he was immediately attracted to Corso, who was straight, but understanding of homosexuality after three years in prison. Ginsberg was even more struck by reading Corso's poems, realizing Corso was "spiritually gifted." Ginsberg introduced Corso to the rest of his inner circle. In their first meeting at the Pony Stable, Corso showed Ginsberg a poem about a woman who lived across the street from him and sunbathed naked in the window. Amazingly, the woman happened to be Ginsberg's girlfriend that he was living with during one of his forays into heterosexuality. Ginsberg took Corso over to their apartment. There the woman proposed sex with Corso, who was still very young and fled in fear. Ginsberg introduced Corso to Kerouac and Burroughs and they began to travel together. Ginsberg and Corso remained lifelong friends and collaborators.[19]

Shortly after this period in Ginsberg's life, he became romantically involved with Elise Nada Cowen after meeting her through Alex Greer, a philosophy professor at Barnard College whom she had dated for a while during the burgeoning Beat generation's period of development. As a Barnard student, Elise Cowen extensively read the poetry of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, when she met Joyce Johnson and Leo Skir, among other Beat players. As Cowen had felt a strong attraction to darker poetry most of the time, Beat poetry seemed to provide an allure to what suggests a shadowy side of her persona. While at Barnard, Cowen earned the nickname "Beat Alice" as she had joined a small group of anti-establishment artists and visionaries known to outsiders as beatniks, and one of her first acquaintances at the college was the beat poet Joyce Johnson who later portrayed Cowen in her books, including "Minor Characters" and Come and Join the Dance, which expressed the two women's experiences in the Barnard and Columbia Beat community. Through his association with Elise Cowen, Ginsberg discovered that they shared a mutual friend, Carl Solomon, to whom he later dedicated his most famous poem "Howl". This poem is considered an autobiography of Ginsberg up to 1955, and a brief history of the Beat Generation through its references to his relationship to other Beat artists of that time.

The Blake vision

In 1948 in an apartment in Harlem, Ginsberg had an auditory hallucination while reading the poetry of William Blake (later referred to as his "Blake vision"). At first, Ginsberg claimed to have heard the voice of God, but later interpreted the voice as that of Blake himself reading Ah, Sunflower, The Sick Rose, and Little Girl Lost, also described by Ginsberg as "voice of the ancient of days". The experience lasted several days. Ginsberg believed that he had witnessed the interconnectedness of the universe. He looked at lattice-work on the fire escape and realized some hand had crafted that; he then looked at the sky and intuited that some hand had crafted that also, or rather, that the sky was the hand that crafted itself. He explained that this hallucination was not inspired by drug use, but said he sought to recapture that feeling later with various drugs.[19] Ginsberg stated: "living blue hand itself [E]xistence itself was God" and "[I] felt a sudden awakening into a totally deeper real universe."San Francisco Renaissance

Ginsberg moved to San Francisco during the 1950s. Before, Howl and Other Poems was published in 1956 by City Lights Bookshop, he worked as a market researcher.[41]In 1954, in San Francisco, Ginsberg met Peter Orlovsky (1933–2010), with whom he fell in love and who remained his lifelong partner.[19] Selections from their correspondence have been published.[42]

Also in San Francisco, Ginsberg met members of the San Francisco Renaissance (James Broughton, Robert Duncan, Madeline Gleason and Kenneth Rexroth) and other poets who would later be associated with the Beat Generation in a broader sense. Ginsberg's mentor William Carlos Williams wrote an introductory letter to San Francisco Renaissance figurehead Kenneth Rexroth, who then introduced Ginsberg into the San Francisco poetry scene. There, Ginsberg also met three budding poets and Zen enthusiasts who had become friends at Reed College: Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Lew Welch. In 1959, along with poets John Kelly, Bob Kaufman, A. D. Winans, and William Margolis, Ginsberg was one of the founders of the Beatitude poetry magazine.

Wally Hedrick — a painter and co-founder of the Six Gallery – approached Ginsberg in mid-1955 and asked him to organize a poetry reading at the Six Gallery. At first, Ginsberg refused, but once he had written a rough draft of "Howl", he changed his "fucking mind", as he put it.[39] Ginsberg advertised the event as "Six Poets at the Six Gallery". One of the most important events in Beat mythos, known simply as "The Six Gallery reading" took place on October 7, 1955.[43] The event, in essence, brought together the East and West Coast factions of the Beat Generation. Of more personal significance to Ginsberg, the reading that night included the first public presentation of "Howl", a poem that brought worldwide fame to Ginsberg and to many of the poets associated with him. An account of that night can be found in Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums, describing how change was collected from audience members to buy jugs of wine, and Ginsberg reading passionately, drunken, with arms outstretched.

Ginsberg's principal work, "Howl", is well known for its opening line: "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked...." "Howl" was considered scandalous at the time of its publication, because of the rawness of its language. Shortly after its 1956 publication by San Francisco's City Lights Bookstore, it was banned for obscenity. The ban became a cause célèbre among defenders of the First Amendment, and was later lifted, after Judge Clayton W. Horn declared the poem to possess redeeming artistic value.[19]

Ginsberg and Shig Murao, the City Lights manager who was jailed for selling "Howl," became lifelong friends.[44]

Biographical references in "Howl"

Ginsberg claimed at one point that all of his work was an extended biography (like Kerouac's Duluoz Legend). "Howl" is not only a biography of Ginsberg's experiences before 1955, but also a history of the Beat Generation. Ginsberg also later claimed that at the core of "Howl" were his unresolved emotions about his schizophrenic mother. Though "Kaddish" deals more explicitly with his mother (so explicitly that a line-by-line analysis would be simultaneously over-exhaustive and relatively unrevealing), "Howl" in many ways is driven by the same emotions. "Howl" chronicles the development of many important friendships throughout Ginsberg’s life. He begins the poem with “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness”, which sets the stage for Ginsberg to describe Cassady and Solomon, immortalizing them into American literature.[39] This madness was the “angry fix” that society needed to function—madness was its disease. In the poem, Ginsberg focused on “Carl Solomon! I’m with you in Rockland”, and, thus, turned Solomon into an archetypal figure searching for freedom from his “straightjacket”. Though references in most of his poetry reveal much about his biography, his relationship to other members of the Beat Generation, and his own political views, "Howl", his most famous poem, is still perhaps the best place to start.To Paris and the "Beat Hotel"

In 1957, Ginsberg surprised the literary world by abandoning San Francisco. After a spell in Morocco, he and Peter Orlovsky joined Gregory Corso in Paris. Corso introduced them to a shabby lodging house above a bar at 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur that was to become known as the Beat Hotel. They were soon joined by Burroughs and others. It was a productive, creative time for all of them. There, Ginsberg finished his epic poem "Kaddish", Corso composed Bomb and Marriage, and Burroughs (with help from Ginsberg and Corso) put together Naked Lunch, from previous writings. This period was documented by the photographer Harold Chapman, who moved in at about the same time, and took pictures constantly of the residents of the "hotel" until it closed in 1963. During 1962–3, Ginsberg and Orlovsky travelled extensively across India, living half a year at a time in Benaras and Calcutta. Also during this time, he formed friendships with some of the prominent young Bengali poets of the time including Shakti Chattopadhyay and Sunil Gangopadhyay. He lived with the future President of India Pratibha Patil in Varanasi in 1962. Ginsberg had several political connections in India most notably Pupul Jayakar who helped him escape imprisonment during the Sino-Indian War.England and the International Poetry Incarnation

In May 1965, Allen Ginsberg arrived in London, and offered to read anywhere for free.[45] Shortly after his arrival, he gave a reading at Better Books, which was described by Jeff Nuttall as "the first healing wind on a very parched collective mind".[45] Tom McGrath wrote "This could well turn out to have been a very significant moment in the history of England – or at least in the history of English Poetry".[46]Soon after the bookshop reading, plans were hatched for the International Poetry Incarnation,[46] which was held at the Royal Albert Hall in London on June 11, 1965. The event attracted an audience of 7,000, who heard readings and live and tape performances by a wide variety of figures, including Ginsberg, Adrian Mitchell, Alexander Trocchi, Harry Fainlight, Anselm Hollo, Christopher Logue, George Macbeth, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael Horovitz, Simon Vinkenoog, Spike Hawkins and Tom McGrath. The event was organized by Ginsberg's friend, the filmmaker Barbara Rubin.[47][48]

Peter Whitehead documented the event on film and released it as Wholly Communion. A book featuring images from the film and some of the poems that were performed was also published under the same title by Lorrimer in the UK and Grove Press in US.

Continuing literary activity

Though the term "Beat" is most accurately applied to Ginsberg and his closest friends (Corso, Orlovsky, Kerouac, Burroughs, etc.), the term "Beat Generation" has become associated with many of the other poets Ginsberg met and became friends with in the late 1950s and early 1960s. A key feature of this term seems to be a friendship with Ginsberg. Friendship with Kerouac or Burroughs might also apply, but both writers later strove to disassociate themselves from the name "Beat Generation." Part of their dissatisfaction with the term came from the mistaken identification of Ginsberg as the leader. Ginsberg never claimed to be the leader of a movement. He claimed that many of the writers with whom he had become friends in this period shared many of the same intentions and themes. Some of these friends include: David Amram, Bob Kaufman; LeRoi Jones before he became Amiri Baraka, who, after reading "Howl", wrote a letter to Ginsberg on a sheet of toilet paper; Diane DiPrima; Jim Cohn; poets associated with the Black Mountain College such as Robert Creeley and Denise Levertov; poets associated with the New York School such as Frank O'Hara and Kenneth Koch.

Later in his life, Ginsberg formed a bridge between the beat movement of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s, befriending, among others, Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey, and Bob Dylan. Ginsberg gave his last public reading at Booksmith, a bookstore in the Haight Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, a few months before his death.[49]

Buddhism and Krishnaism

Ginsberg's spiritual journey began early on with his spontaneous visions, and continued with an early trip to India. A chance encounter on a New York City street with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (they both tried to catch the same cab), a Kagyu and Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist master, led to Trungpa becoming his friend and lifelong teacher.[citation needed] Ginsberg helped Trungpa (and New York poet Anne Waldman) in founding the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado.[50]Ginsberg was also involved with Krishnaism. He had started incorporating chanting the Hare Krishna mantra into his religious practice in the mid sixties. After learning that A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the Hare Krishna movement in the Western world had rented a store front in New York, he befriended him, visiting him often and suggesting publishers for his books, and a fruitful relationship began. This relationship is documented by Satsvarupa Das Goswami in his biographical account Srila Prabhupada Lilamrta. Ginsberg donated money, materials, and his reputation to help the Swami establish the first temple, and toured with him to promote his cause.[51]

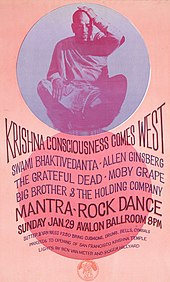

Despite disagreeing with many of Bhaktivedanta Swami's required prohibitions, Ginsberg often sang the Hare Krishna mantra publicly as part of his philosophy[52] and declared that it brought a state of ecstasy.[53] He was glad that Bhaktivedanta Swami, an authentic swami from India, was now trying to spread the chanting in America. Along with other counterculture ideologists like Timothy Leary, Gary Snyder, and Alan Watts, Ginsberg hoped to incorporate Bhaktivedanta Swami and his chanting into the hippie movement, and agreed to take part in the Mantra-Rock Dance concert and to introduce the swami to the Haight-Ashbury hippie community.[52][54][nb 1]

On January 17, 1967, Allen Ginsberg helped plan and organize a reception for Bhaktivedanta Swami at the San Francisco Airport, where fifty to a hundred hippies greeted the Swami, chanting Hare Krishna in the airport lounge with flowers in hands.[55][nb 2] To further support and promote Bhaktivendata Swami's message and chanting in San Francisco, Allen Ginsberg agreed to attend the Mantra-Rock Dance—a musical event held at the Avalon Ballroom by the San Francisco Hare Krishna temple. It featured some leading rock bands of the time: Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, The Grateful Dead, and Moby Grape, who performed there along with the Hare Krishna founder Bhaktivedanta Swami and donated proceeds to the Krishna temple. Ginsberg introduced Bhaktivedanta Swami to some three thousand hippies in the audience and led the chanting of the Hare Krishna mantra.[56][57][58]

Music and chanting were both important parts of Ginsberg's live delivery during poetry readings.[59] He often accompanied himself on a harmonium, and was often accompanied by a guitarist. When Ginsberg asked if he could sing a song in praise of Lord Krishna on William F. Buckley, Jr.'s TV show Firing Line on September 3, 1968, Buckley acceded and the poet chanted slowly as he played dolefully on a harmonium. According to Richard Brookhiser, an associate of Buckley's, the host commented that it was "the most unharried Krishna I've ever heard."[60]

At the 1967 Human Be-In in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and the 1970 Black Panther rally at Yale campus Allen chanted "Om" repeatedly over a sound system for hours on end.[61]

Ginsberg further brought mantras into the world of rock and roll when he recited the Heart Sutra in the song "Ghetto Defendant". The song appears on the 1982 album Combat Rock by British first wave punk band The Clash.

Ginsberg came in touch with the Hungryalist poets of Bengal, especially Malay Roy Choudhury, who introduced Ginsberg to the three fishes with one head of Indian emperor Jalaluddin Mohammad Akbar. The three fishes symbolised coexistence of all thought, philosophy and religion.[62]

In spite of Ginsberg's attraction to Eastern religions, the journalist Jane Kramer argues that he, like Whitman, adhered to an "American brand of mysticism" that was, "rooted in humanism and in a romantic and visionary ideal of harmony among men."[63]

Health

In 1960 he was treated for a tropical disease, and it is speculated that he contracted hepatitis from an unsterilized needle administered by a doctor, which played a role in his death forty years later.[64] Ginsberg was a lifelong smoker, and though he tried to quit for health and religious reasons, his busy schedule in later life made it difficult, and he always returned to smoking.In the 1970s Ginsberg suffered two minor strokes which were first diagnosed as Bell's Palsy, which gave him significant paralysis and stroke-like drooping of the muscles in one side of his face.

Later in life, he also suffered constant minor ailments such as high blood pressure. Many of these symptoms were related to stress, but he never slowed down his schedule.[65]

Final years

In 1986 Ginsberg was awarded the Golden Wreath by the Struga Poetry Evenings International Festival in Macedonia, the second American poet to be so awarded since WH Auden. At Struga he met with the other Golden Wreath winners, Bulat Okudzhava and Andrei Voznesensky. Ginsberg won a 1974 National Book Award for The Fall of America (split with Adrienne Rich, Diving Into the Wreck).[12] In 1993, the French Minister of Culture made him a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres.Ginsberg continued to help his friends as much as he could, going so far as to give money to Herbert Huncke out of his own pocket, and housing a broke and drug addicted Harry Smith.

After returning home from the hospital for the last time, where he had been unsuccessfully treated for congestive heart failure, Ginsberg continued making phone calls to say goodbye to nearly everyone in his addressbook. Some of the phone calls, including one with Johnny Depp, were sad and interrupted by crying, while other were joyous and optimistic.[66]

With the exception of a special guest appearance at the NYU Poetry Slam on February 20, 1997, Ginsberg gave what is thought to be his last reading at The Booksmith in San Francisco on December 16, 1996. He died April 5, 1997, surrounded by family and friends in his East Village loft in New York City, succumbing to liver cancer via complications of hepatitis. He was 70 years old.[20] Ginsberg continued to write through his final illness, with his last poem, "Things I'll Not Do (Nostalgias)", written on March 30.[67]

In the beginning of April, Ginsberg was told by doctors that he did not have much time left, and on the eve of his death, a dozen of his close friends and old lovers decided to sleep overnight in his apartment. Around 2:30 in the morning on April 5, 1997, he began to breathe heavily and laboured in his sleep, awaking his guests. Dr. Joel Gaidemak, Ginsberg's cousin, examined him and said that the end was close; a few moments later he stopped breathing. He died ten years and one day after the death of his teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Gehlek Rinpoche, Ginsberg's guru after the death of Chogyam, had given Peter Hale something to touch to Ginsberg's lips to symbolize his last earthly meal. His body convulsed and he was dead. Gehlek, together with senior Buddhist practitioners, chanted for hours on end after his death. Gehlek explained that they were reiterating lessons Allen Ginsberg had learned in this life, and teaching him new ones he might need in the new state that would follow. After approximately 18 hours, Gehlek pronounced that Ginsberg's "spirit" had left his body.

Gregory Corso, Roy Lichtenstein, Patti Smith and others came by to pay their respect.[68]

Ginsberg is buried in his family plot in Gomel Chesed Cemetery.[69] He was survived by Orlovsky.

In 1998, such writers as Catfish McDaris read at a gathering at Ginsberg's farm to honour Allen and the beatniks.[70]

Social and political activism

Free speech

Ginsberg's willingness to talk about taboo subjects made him a controversial figure during the conservative 1950s, and a significant figure in the 1960s. In the mid-1950s, no reputable publishing company would even consider publishing "Howl". At the time, such "sex talk" employed in "Howl" was considered by some to be vulgar or even a form of pornography, and could be prosecuted under law.[39] Ginsberg used phrases such as "cocksucker", "fucked in the ass", and "cunt" as part of the poem's depiction of different aspects of American culture. Numerous books that discussed sex were banned at the time, including Lady Chatterley’s Lover.[39] The sex that Ginsberg painted did not portray the sex between heterosexual married couples, or even long time lovers. Instead, Ginsberg portrayed casual sex, and used this to comment on the emptiness and constant hunger that could exist in the lives of Americans.[39]For example, in "Howl", Ginsberg praises the man "who sweetened the snatches of a million girls". Ginsberg used gritty descriptions and explicit sexual language, pointing out the man "who lounged hungry and lonesome through Houston seeking jazz or sex or soup." In his poetry, Ginsberg also discussed the then-taboo topic of homosexuality. The explicit sexual language that filled "Howl" eventually led to an important trial on First Amendment issues. Ginsberg's publisher was brought up on charges for publishing pornography, and the outcome led to a judge going on record dismissing charges because the poem carried "redeeming social importance",[71] thus setting an important legal precedent. Ginsberg continued to broach controversial subjects throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. From 1970–1996, Ginsberg had a long-term affiliation with PEN American Center with efforts to defend free expression. When explaining how he approached controversial topics, he often pointed to Herbert Huncke: he said that when he first got to know Huncke in the 1940s, Ginsberg saw that he was sick from his heroin addiction, but at the time heroin was a taboo subject and Huncke was left with nowhere to go for help.[72]

Role in Vietnam War protests

Ginsberg was a signer of the anti-war manifesto "A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority," circulated among draft resistors in 1967 by members of the radical intellectual collective RESIST. Other signers and RESIST members included Mitchell Goodman, Henry Braun, Denise Levertov, Noam Chomsky, William Sloane Coffin, Dwight Macdonald, Robert Lowell, and Norman Mailer.[73][74] In 1968, Ginsberg signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[75]He was present the night of the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot in 1988 and provided an eyewitness account to The New York Times.[76]

Bangladeshi war victims

Allen Ginsberg will also be remembered by Bengalis for calling the world's attention to the suffering of victims during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. He wrote his legendary 152-line poem, September on Jessore Road, after visiting refugee camps and witnessing the plight of millions fleeing the violence.Millions of daughters walk in the mudGinsberg's poem also serves as an indictment of the United States:

Millions of children wash in the flood

A Million girls vomit & groan

Millions of families hopeless alone[77]

Where are the helicopters of U.S. AID?Out of the poem, he made a song that was performed by Bob Dylan, other musicians and Ginsberg himself.[78]

Smuggling dope in Bangkok's green shade.

Where is America's Air Force of Light?

Bombing North Laos all day and all night?

The last few lines of the poem read:

Millions of babies in pain

Millions of mothers in rain

Millions of brothers in woe

Millions of children nowhere to go[79]

Relationship to communism

Ginsberg talked openly about his connections with communism and his admiration for past communist heroes and the labor movement at a time when the Red Scare and McCarthyism were still raging. He admired Castro and many other quasi-Marxist figures from the 20th century.[80][81] In "America" (1956), Ginsberg writes: "America, I used to be a communist when I was a kid I'm not sorry...." Biographer Jonah Raskin has claimed that, despite his often stark opposition to communist orthodoxy, Ginsberg held "his own idiosyncratic version of communism".[82] On the other hand, when Donald Manes, a New York City politician, publicly accused Ginsberg of being a member of the Communist Party, Ginsberg objected: "I am not, as a matter of fact, a member of the Communist party, nor am I dedicated to the overthrow of [the U.S.] government or any government by violence.... I must say that I see little difference between the armed and violent governments both Communist and Capitalist that I have observed..."[83]Ginsberg travelled to several communist countries to promote free speech. He claimed that communist countries, such as China, welcomed him because they thought he was an enemy of capitalism, but often turned against him when they saw him as a trouble maker. For example, in 1965 Ginsberg was deported from Cuba for publicly protesting at the persecution of homosexuals and referring to Che Guevara as "cute".[84] The Cubans sent him to Czechoslovakia, where one week after being named the Král majálesu ("King of May"[85] – a students' festivity, celebrating spring and student life), Ginsberg was labelled an "immoral menace" by the Czechoslovak government because of his free expression of radical ideas, and was then deported on May 7, 1965[84][86] by order of the state security agency StB.[87] Václav Havel points to Ginsberg as an important inspiration in striving for freedom.[88]

Gay rights

One contribution that is often considered his most significant and most controversial was his openness about homosexuality. Ginsberg was an early proponent of freedom for gay people. In 1943, he discovered within himself "mountains of homosexuality." He expressed this desire openly and graphically in his poetry. He also struck a note for gay marriage by listing Peter Orlovsky, his lifelong companion, as his spouse in his Who's Who entry.Subsequent gay writers saw his frank talk about homosexuality as an opening to speak more openly and honestly about something often before only hinted at or spoken of in metaphor.[72]

In writing about sexuality in graphic detail and in his frequent use of language seen as indecent, he challenged—and ultimately changed—obscenity laws. He was a staunch supporter of others whose expression challenged obscenity laws (William S. Burroughs and Lenny Bruce, for example).

Association with NAMBLA

Ginsberg was a supporter and member of North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA).[89] In "Thoughts on NAMBLA", a 1994 essay published in the collection Deliberate Prose, Ginsberg stated, "I joined NAMBLA in defense of free speech."Demystification of drugs

Ginsberg also talked often about drug use. Throughout the 1960s he took an active role in the demystification of LSD, and, with Timothy Leary, worked to promote its common use. He was also for many decades an advocate of marijuana legalization, and, at the same time, warned his audiences against the hazards of tobacco in his Put Down Your Cigarette Rag (Don't Smoke): "Don't Smoke Don't Smoke Nicotine Nicotine No / No don't smoke the official Dope Smoke Dope Dope."CIA drug trafficking

Through his own drug use, and the drug use of his friends and associates, Ginsberg became more and more preoccupied with the American government's relationship to drug use within and outside the nation. He worked closely with Alfred W. McCoy who was writing The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia which tracked the history of the American government's involvement in illegal opium dealing around the world. This would affirm Ginsberg's suspicions that the government and the CIA were involved in drug trafficking. In addition to working with McCoy, Ginsberg personally confronted Richard Helms, the director of the CIA in the 1970s, but he was simply brushed off as being "full of beans". Allen wrote many essays and articles, researching and compiling evidence of CIA's involvement, but it would take ten years, and the publication of McCoy's book in 1972, before anyone took him seriously. In 1978 Allen received a note from the chief editor of the New York Times, apologizing for not taking his allegations seriously so many years previous.[90] The political subject is dealt with in the song/poem "CIA Dope calypso".Work

Though early on Ginsberg had intentions to be a labor lawyer, he wrote poetry for most of his life. Most of his very early poetry was written in formal rhyme and meter like that of his father or his idol William Blake. His admiration for the writing of Jack Kerouac inspired him to take poetry more seriously. Though he took odd jobs to support himself, in 1955, upon the advice of a psychiatrist, Ginsberg dropped out of the working world to devote his entire life to poetry. Soon after, he wrote "Howl", the poem that brought him and his friends much fame and allowed him to live as a professional poet for the rest of his life. Later in life, Ginsberg entered academia, teaching poetry as Distinguished Professor of English at Brooklyn College from 1986 until his death.Inspiration from friends

Since Ginsberg's poetry is intensely personal, and since much of the vitality of those associated with the beat generation comes from mutual inspiration, much credit for style, inspiration, and content can be given to Ginsberg's friends.Ginsberg claimed throughout his life that his biggest inspiration was Kerouac's concept of "spontaneous prose". He believed literature should come from the soul without conscious restrictions. Ginsberg was much more prone to revise than Kerouac. For example, when Kerouac saw the first draft of "Howl" he disliked the fact that Ginsberg had made editorial changes in pencil (transposing "negro" and "angry" in the first line, for example). Kerouac only wrote out his concepts of Spontaneous Prose at Ginsberg's insistence because Ginsberg wanted to learn how to apply the technique to his poetry.[19]

The inspiration for "Howl" was Ginsberg's friend, Carl Solomon, and "Howl" is dedicated to Solomon (whom Ginsberg also directly addresses in the third section of the poem). Solomon was a Dada and Surrealism enthusiast (he introduced Ginsberg to Artaud) who suffered bouts of depression. Solomon wanted to commit suicide, but he thought a form of suicide appropriate to dadaism would be to go to a mental institution and demand a lobotomy. The institution refused, giving him many forms of therapy, including electroshock therapy. Much of the final section of the first part of "Howl" is a description of this.

Ginsberg used Solomon as an example of all those ground down by the machine of "Moloch". Moloch, to whom the second section is addressed, is a Levantine god to whom children were sacrificed. Ginsberg may have gotten the name from the Kenneth Rexroth poem "Thou Shalt Not Kill", a poem about the death of one of Ginsberg's heroes, Dylan Thomas. Moloch is mentioned a few times in the Torah and references to Ginsberg's Jewish background are not infrequent in his work. Ginsberg said the image of Moloch was inspired by peyote visions he had of the Francis Drake Hotel in San Francisco which appeared to him as a skull; he took it as a symbol of the city (not specifically San Francisco, but all cities). Ginsberg later acknowledged in various publications and interviews that behind the visions of the Francis Drake Hotel were memories of the Moloch of Fritz Lang's film Metropolis (1927) and of the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward.[91] Moloch has subsequently been interpreted as any system of control, including the conformist society of post–World War II America, focused on material gain, which Ginsberg frequently blamed for the destruction of all those outside of societal norms.[19]

He also made sure to emphasize that Moloch is a part of all of us: the decision to defy socially created systems of control—and therefore go against Moloch—is a form of self-destruction. Many of the characters Ginsberg references in "Howl", such as Neal Cassady and Herbert Huncke, destroyed themselves through excessive substance abuse or a generally wild lifestyle. The personal aspects of "Howl" are perhaps as important as the political aspects. Carl Solomon, the prime example of a "best mind" destroyed by defying society, is associated with Ginsberg's schizophrenic mother: the line "with mother finally ****** (fucked)" comes after a long section about Carl Solomon, and in Part III, Ginsberg says: "I'm with you in Rockland where you imitate the shade of my mother." Ginsberg later admitted that the drive to write "Howl" was fueled by sympathy for his ailing mother, an issue which he was not yet ready to deal with directly. He dealt with it directly with 1959's "Kaddish",[19] which had its first public reading at a Catholic Worker Friday Night meeting, possibly due to its associations with Thomas Merton.[92]

Inspiration from mentors and idols

Ginsberg's poetry was strongly influenced by Modernism (most importantly the American style of Modernism pioneered by William Carlos Williams), Romanticism (specifically William Blake and John Keats), the beat and cadence of jazz (specifically that of bop musicians such as Charlie Parker), and his Kagyu Buddhist practice and Jewish background. He considered himself to have inherited the visionary poetic mantle handed down from the English poet and artist William Blake, the American poet Walt Whitman and the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. The power of Ginsberg's verse, its searching, probing focus, its long and lilting lines, as well as its New World exuberance, all echo the continuity of inspiration that he claimed.[19][72][88]He corresponded with William Carlos Williams, who was then in the middle of writing his epic poem Paterson about the industrial city near his home. After attending a reading by Williams, Ginsberg sent the older poet several of his poems and wrote an introductory letter. Most of these early poems were rhymed and metered and included archaic pronouns like "thee." Williams disliked the poems and told Ginsberg, "In this mode perfection is basic, and these poems are not perfect."[19][72][88]

Though he disliked these early poems, Williams loved the exuberance in Ginsberg's letter. He included the letter in a later part of Paterson. He encouraged Ginsberg not to emulate the old masters, but to speak with his own voice and the voice of the common American. From Williams, Ginsberg learned to focus on strong visual images, in line with Williams' own motto "No ideas but in things." Studying Williams' style led to a tremendous shift from the early formalist work to a loose, colloquial free verse style. Early breakthrough poems include Bricklayer's Lunch Hour and Dream Record.[19][88]

Carl Solomon introduced Ginsberg to the work of Antonin Artaud (To Have Done with the Judgement of God and Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society), and Jean Genet (Our Lady of the Flowers). Philip Lamantia introduced him to other Surrealists and Surrealism continued to be an influence (for example, sections of "Kaddish" were inspired by André Breton's Free Union). Ginsberg claimed that the anaphoric repetition of "Howl" and other poems was inspired by Christopher Smart in such poems as Jubilate Agno. Ginsberg also claimed other more traditional influences, such as: Franz Kafka, Herman Melville, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Edgar Allan Poe, and even Emily Dickinson.[19][72]

Ginsberg also made an intense study of haiku and the paintings of Paul Cézanne, from which he adapted a concept important to his work, which he called the Eyeball Kick. He noticed in viewing Cézanne's paintings that when the eye moved from one color to a contrasting color, the eye would spasm, or "kick." Likewise, he discovered that the contrast of two seeming opposites was a common feature in haiku. Ginsberg used this technique in his poetry, putting together two starkly dissimilar images: something weak with something strong, an artifact of high culture with an artifact of low culture, something holy with something unholy. The example Ginsberg most often used was "hydrogen jukebox" (which later became the title of a song cycle composed by Philip Glass with lyrics drawn from Ginsberg's poems). Another example is Ginsberg's observation on Bob Dylan during Dylan's hectic and intense 1966 electric-guitar tour, fuelled by a cocktail of amphetamines,[93] opiates,[94] alcohol,[95] and psychedelics,[96] as a Dexedrine Clown. The phrases "eyeball kick" and "hydrogen jukebox" both show up in "Howl", as well as a direct quote from Cézanne: "Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus".[72]

Inspiration From Music

Allen Ginsberg also found inspiration in music. He frequently included music in his poetry. He wrote and recorded music to accompany William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. He also recorded a hand full of other albums. To create music for Howl and Wichita Vortex Sutra he worked with the neo-classical composer, Philip Glass.Ginsberg has worked with, inspired, and drew inspiration from artists such as, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, The Clash, Patti Smith, Phil Ochs, and The Fugs.[41]

Allen Ginsberg and Paul McCartney This recording is a follow up to Ginsberg's Ballad of the Skeletons.

"Ballad of the Skeletons" with music by Philip Glass and Paul McCartney playing guitar.

Style and technique

From the study of his idols and mentors and the inspiration of his friends—not to mention his own experiments—Ginsberg developed an individualistic style that's easily identified as Ginsbergian.[97] "Howl" came out during a potentially hostile literary environment, less welcoming to non-traditional, free verse poetry; there was a renewed focus on form and structure among academic poets and critics partly inspired by New Criticism. Consequently, Ginsberg often had to defend his choice to employ long, free verse lines, often citing Whitman's free verse used in Leaves of Grass as a precursor.[citation needed] Ginsberg claimed Whitman's long line was a dynamic technique few other poets had ventured to develop further, and Whitman is also often compared to Ginsberg because their poetry sexualized aspects of the male form.[19][72][88]Ginsberg believed strongly that traditional formalist considerations were archaic and did not apply to reality.[citation needed] Though some critics, like Diana Trilling, have pointed to Ginsberg's occasional use of meter (for example the anapest of "who came back to Denver and waited in vain"), Ginsberg denied any intention toward meter and claimed instead that his idea of meter followed the "natural" poetic voice.[citation needed]

Ginsberg said that he learned from William Carlos Williams that natural speech is occasionally dactylic so poetry that imitates natural speech will sometimes fall into a dactylic structure but only accidentally.[citation needed] Like Williams, Ginsberg's line breaks were often determined by breath: one line in "Howl", for example, should be read in one breath. Ginsberg claimed he developed such a long line because he had long breaths.[citation needed]

Many of Ginsberg's early long line experiments contain some sort of anaphora, repetition of a "fixed base" (for example "who" in "Howl", "America" in America) and this has become a recognizable feature of Ginsberg's style.[citation needed] He said later this was a crutch because he lacked confidence; he did not yet trust "free flight".[citation needed] In the 1960s, after employing it in some sections of "Kaddish" ("caw" for example) he, for the most part, abandoned the anaphoric form.[72][88]

Several of his earlier experiments with methods for formatting poems as a whole became regular aspects of his style in later poems. In the original draft of "Howl", each line is in a "stepped triadic" format reminiscent of William Carlos Williams.[citation needed] But he abandoned the "stepped triadic" when he developed his long line although the stepped lines showed up later, most significantly in the travelogues of The Fall of America.[citation needed] "Howl" and "Kaddish", arguably his two most important poems, are both organized as an inverted pyramid, with larger sections leading to smaller sections. In America, he also experimented with a mix of longer and shorter lines.[72][88]

In "Howl" and in his other poetry, Ginsberg drew inspiration from the epic, free verse style of the 19th-century American poet Walt Whitman.[98] Both wrote passionately about the promise (and betrayal) of American democracy, the central importance of erotic experience, and the spiritual quest for the truth of everyday existence. J. D. McClatchy, editor of the Yale Review, called Ginsberg "the best-known American poet of his generation, as much a social force as a literary phenomenon." McClatchy added that Ginsberg, like Whitman, "was a bard in the old manner – outsized, darkly prophetic, part exuberance, part prayer, part rant. His work is finally a history of our era's psyche, with all its contradictory urges." McClatchy's barbed eulogies define the essential difference between Ginsberg ("a beat poet whose writing was ... journalism raised by combining the recycling genius with a generous mimic-empathy, to strike audience-accesible chords; always lyrical and sometimes truly poetic") and Kerouac ("a poet of singular brilliance, the brightest luminary of a 'beat generation' he came to symbolise in popular culture... [though] in reality he far surpassed his contemporaries.... Kerouac is an originating genius, exploring then answering - like Rimbaud a century earlier, by necessity more than by choice - the demands of authentic self-expression as applied to the evolving quicksilver mind of America's only literary virtuoso..."):[17]

Bibliography

- Howl and Other Poems (1956) ISBN 978-0-87286-017-9

- Kaddish and Other Poems (1961) ISBN 978-0-87286-019-3

- Empty Mirror: Early Poems (1961) ISBN 978-0-87091-030-2

- Reality Sandwiches (1963) ISBN 978-0-87286-021-6

- The Yage Letters (1963) – with William S. Burroughs

- Planet News (1968) ISBN 978-0-87286-020-9

- First Blues: Rags, Ballads & Harmonium Songs 1971 - 1974 (1975), ISBN 0-916190-05-6

- The Gates of Wrath: Rhymed Poems 1948–1951 (1972) ISBN 978-0-912516-01-1

- The Fall of America: Poems of These States (1973) ISBN 978-0-87286-063-6

- Iron Horse (1972)

- Sad Dust Glories: poems during work summer in woods (1975)

- Mind Breaths (1978) ISBN 978-0-87286-092-6

- Plutonian Ode: Poems 1977–1980 (1981) ISBN 978-0-87286-125-1

- Collected Poems 1947–1980 (1984) ISBN 978-0-06-015341-0. Republished with later material added as Collected Poems 1947-1997, New York, Harper Collins, 2006

- White Shroud Poems: 1980–1985 (1986)

- Cosmopolitan Greetings Poems: 1986–1993 (1994)

- Howl Annotated (1995)

- Illuminated Poems (1996)

- Selected Poems: 1947–1995 (1996)

- Death and Fame: Poems 1993–1997 (1999)

- Deliberate Prose 1952–1995 (2000)

- Howl & Other Poems 50th Anniversary Edition (2006) ISBN 978-0-06-113745-7

- The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice: First Journals and Poems 1937-1952 (Da Capo Press, 2006)

- The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder (Counterpoint, 2009)

- I Greet You At The Beginning of a Great Career (2015)