The field lines of a vector field F through surfaces with unit normal n, the angle from n to F is θ. Flux is a measure of how much of the field passes through a given surface. F is decomposed into components perpendicular (⊥) and parallel ( ‖ ) to n.

Only the parallel component contributes to flux because it is the

maximum extent of the field passing through the surface at a point, the

perpendicular component does not contribute. Top: Three field lines through a plane surface, one normal to the surface, one parallel, and one intermediate. Bottom: Field line through a curved surface, showing the setup of the unit normal and surface element to calculate flux.

Flux describes the quantity which passes through a surface or substance. A flux is either a concept based in physics or used with applied mathematics. Both concepts have mathematical rigor, enabling comparison of the underlying math when the terminology is unclear. For transport phenomena, flux is a vector quantity, describing the magnitude and direction of the flow of a substance or property. In electromagnetism, flux is a scalar quantity, defined as the surface integral of the component of a vector field perpendicular to the surface at each point.[1]

Terminology

The word flux comes from Latin: fluxus means "flow", and fluere is "to flow".[2] As fluxion, this term was introduced into differential calculus by Isaac Newton.One could argue, based on the work of James Clerk Maxwell,[3] that the transport definition precedes the way the term is used in electromagnetism. The specific quote from Maxwell is:

In the case of fluxes, we have to take the integral, over a surface, of the flux through every element of the surface. The result of this operation is called the surface integral of the flux. It represents the quantity which passes through the surface.According to the first definition, flux may be a single vector, or flux may be a vector field / function of position. In the latter case flux can readily be integrated over a surface. By contrast, according to the second definition, flux is the integral over a surface; it makes no sense to integrate a second-definition flux for one would be integrating over a surface twice. Thus, Maxwell's quote only makes sense if "flux" is being used according to the first definition (and furthermore is a vector field rather than single vector). This is ironic because Maxwell was one of the major developers of what we now call "electric flux" and "magnetic flux" according to the second definition. Their names in accordance with the quote (and first definition) would be "surface integral of electric flux" and "surface integral of magnetic flux", in which case "electric flux" would instead be defined as "electric field" and "magnetic flux" defined as "magnetic field". This implies that Maxwell conceived of these fields as flows/fluxes of some sort.

— James Clerk Maxwell

Given a flux according to the second definition, the corresponding flux density, if that term is used, refers to its derivative along the surface that was integrated. By the Fundamental theorem of calculus, the corresponding flux density is a flux according to the first definition. Given a current such as electric current—charge per time, current density would also be a flux according to the first definition—charge per time per area. Due to the conflicting definitions of flux, and the interchangeability of flux, flow, and current in nontechnical English, all of the terms used in this paragraph are sometimes used interchangeably and ambiguously. Concrete fluxes in the rest of this article will be used in accordance to their broad acceptance in the literature, regardless of which definition of flux the term corresponds to.

Flux as flow rate per unit area

In transport phenomena (heat transfer, mass transfer and fluid dynamics), flux is defined as the rate of flow of a property per unit area, which has the dimensions [quantity]·[time]−1·[area]−1.[4] The area is of the surface the property is flowing "through" or "across". For example, the magnitude of a river's current, i.e. the amount of water that flows through a cross-section of the river each second, or the amount of sunlight energy that lands on a patch of ground each second, are kinds of flux.General mathematical definition (transport)

Here are 3 definitions in increasing order of complexity. Each is a special case of the following. In all cases the frequent symbol j, (or J) is used for flux, q for the physical quantity that flows, t for time, and A for area. These identifiers will be written in bold when and only when they are vectors.First, flux as a (single) scalar:

Second, flux as a scalar field defined along a surface, i.e. a function of points on the surface:

Finally, flux as a vector field:

), and measures the flow through the disk of area A perpendicular to that unit vector. I

is defined picking the unit vector that maximizes the flow around the

point, because the true flow is maximized across the disk that is

perpendicular to it. The unit vector thus uniquely maximizes the

function when it points in the "true direction" of the flow. [Strictly

speaking, this is an abuse of notation because the "arg max" cannot directly compare vectors; we take the vector with the biggest norm instead.]

), and measures the flow through the disk of area A perpendicular to that unit vector. I

is defined picking the unit vector that maximizes the flow around the

point, because the true flow is maximized across the disk that is

perpendicular to it. The unit vector thus uniquely maximizes the

function when it points in the "true direction" of the flow. [Strictly

speaking, this is an abuse of notation because the "arg max" cannot directly compare vectors; we take the vector with the biggest norm instead.]Properties

These direct definition, especially the last, are rather unwieldy. For example, the argmax construction is artificial from the perspective of empirical measurements, when with a Weathervane or similar one can easily deduce the direction of flux at a point. Rather than defining the vector flux directly, it is often more intuitive to state some properties about it. Furthermore, from these properties the flux can uniquely be determined anyway.If the flux j passes through the area at an angle θ to the area normal

, then

, thenFor vector flux, the surface integral of j over a surface S, gives the proper flowing per unit of time through the surface.

. The relation is

. The relation is  . Unlike in the second set of equations, the surface here need not be flat.

. Unlike in the second set of equations, the surface here need not be flat.Finally, we can integrate again over the time duration t1 to t2, getting the total amount of the property flowing through the surface in that time (t2 − t1):

Transport fluxes

Eight of the most common forms of flux from the transport phenomena literature are defined as follows:- Momentum flux, the rate of transfer of momentum across a unit area (N·s·m−2·s−1). (Newton's law of viscosity)[5]

- Heat flux, the rate of heat flow across a unit area (J·m−2·s−1). (Fourier's law of conduction)[6] (This definition of heat flux fits Maxwell's original definition.)[3]

- Diffusion flux, the rate of movement of molecules across a unit area (mol·m−2·s−1). (Fick's law of diffusion)[5]

- Volumetric flux, the rate of volume flow across a unit area (m3·m−2·s−1). (Darcy's law of groundwater flow)

- Mass flux, the rate of mass flow across a unit area (kg·m−2·s−1). (Either an alternate form of Fick's law that includes the molecular mass, or an alternate form of Darcy's law that includes the density.)

- Radiative flux, the amount of energy transferred in the form of photons at a certain distance from the source per unit area per second (J·m−2·s−1). Used in astronomy to determine the magnitude and spectral class of a star. Also acts as a generalization of heat flux, which is equal to the radiative flux when restricted to the electromagnetic spectrum.

- Energy flux, the rate of transfer of energy through a unit area (J·m−2·s−1). The radiative flux and heat flux are specific cases of energy flux.

- Particle flux, the rate of transfer of particles through a unit area ([number of particles] m−2·s−1)

Chemical diffusion

As mentioned above, chemical molar flux of a component A in an isothermal, isobaric system is defined in Fick's law of diffusion as:This flux has units of mol·m−2·s−1, and fits Maxwell's original definition of flux.[3]

For dilute gases, kinetic molecular theory relates the diffusion coefficient D to the particle density n = N/V, the molecular mass m, the collision cross section

, and the absolute temperature T by

, and the absolute temperature T byIn turbulent flows, the transport by eddy motion can be expressed as a grossly increased diffusion coefficient.

Quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics, particles of mass m in the quantum state ψ(r, t) have a probability density defined asFlux as a surface integral

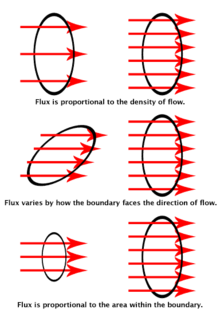

The flux visualized. The rings show the surface boundaries. The red

arrows stand for the flow of charges, fluid particles, subatomic

particles, photons, etc. The number of arrows that pass through each

ring is the flux.

General mathematical definition (surface integral)

As a mathematical concept, flux is represented by the surface integral of a vector field,[10]The surface has to be orientable, i.e. two sides can be distinguished: the surface does not fold back onto itself. Also, the surface has to be actually oriented, i.e. we use a convention as to flowing which way is counted positive; flowing backward is then counted negative.

The surface normal is usually directed by the right-hand rule.

Conversely, one can consider the flux the more fundamental quantity and call the vector field the flux density.

Often a vector field is drawn by curves (field lines) following the "flow"; the magnitude of the vector field is then the line density, and the flux through a surface is the number of lines. Lines originate from areas of positive divergence (sources) and end at areas of negative divergence (sinks).

See also the image at right: the number of red arrows passing through a unit area is the flux density, the curve encircling the red arrows denotes the boundary of the surface, and the orientation of the arrows with respect to the surface denotes the sign of the inner product of the vector field with the surface normals.

If the surface encloses a 3D region, usually the surface is oriented such that the influx is counted positive; the opposite is the outflux.

The divergence theorem states that the net outflux through a closed surface, in other words the net outflux from a 3D region, is found by adding the local net outflow from each point in the region (which is expressed by the divergence).

If the surface is not closed, it has an oriented curve as boundary. Stokes' theorem states that the flux of the curl of a vector field is the line integral of the vector field over this boundary. This path integral is also called circulation, especially in fluid dynamics. Thus the curl is the circulation density.

We can apply the flux and these theorems to many disciplines in which we see currents, forces, etc., applied through areas.

Electromagnetism

One way to better understand the concept of flux in electromagnetism is by comparing it to a butterfly net. The amount of air moving through the net at any given instant in time is the flux. If the wind speed is high, then the flux through the net is large. If the net is made bigger, then the flux is larger even though the wind speed is the same. For the most air to move through the net, the opening of the net must be facing the direction the wind is blowing. If the net is parallel to the wind, then no wind will be moving through the net. The simplest way to think of flux is "how much air goes through the net", where the air is a velocity field and the net is the boundary of an imaginary surface.Electric flux

An electric "charge," such as a single electron in space, has a magnitude defined in coulombs. Such a charge has an electric field surrounding it. In pictorial form, an electric field is shown as a dot radiating "lines of flux" called Gauss lines.[11] Electric Flux Density is the amount of electric flux, the number of "lines," passing through a given area. Units are Gauss/square meter.[12]Two forms of electric flux are used, one for the E-field:[13][14]

If one considers the flux of the electric field vector, E, for a tube near a point charge in the field the charge but not containing it with sides formed by lines tangent to the field, the flux for the sides is zero and there is an equal and opposite flux at both ends of the tube. This is a consequence of Gauss's Law applied to an inverse square field. The flux for any cross-sectional surface of the tube will be the same. The total flux for any surface surrounding a charge q is q/ε0.[15]

In free space the electric displacement is given by the constitutive relation D = ε0 E, so for any bounding surface the D-field flux equals the charge QA within it. Here the expression "flux of" indicates a mathematical operation and, as can be seen, the result is not necessarily a "flow", since nothing actually flows along electric field lines.

Magnetic flux

The magnetic flux density (magnetic field) having the unit Wb/m2 (Tesla) is denoted by B, and magnetic flux is defined analogously:[13][14]The time-rate of change of the magnetic flux through a loop of wire is minus the electromotive force created in that wire. The direction is such that if current is allowed to pass through the wire, the electromotive force will cause a current which "opposes" the change in magnetic field by itself producing a magnetic field opposite to the change. This is the basis for inductors and many electric generators.

Poynting flux

Using this definition, the flux of the Poynting vector S over a specified surface is the rate at which electromagnetic energy flows through that surface, defined like before:[14]Confusingly, the Poynting vector is sometimes called the power flux, which is an example of the first usage of flux, above.[16] It has units of watts per square metre (W/m2).