From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Oligonucleotide synthesis is the chemical synthesis of relatively short fragments of

nucleic acids with defined chemical structure (

sequence).

The technique is extremely useful in current laboratory practice

because it provides a rapid and inexpensive access to custom-made

oligonucleotides of the desired sequence. Whereas

enzymes synthesize

DNA and

RNA only in a

5' to 3' direction,

chemical oligonucleotide synthesis does not have this limitation,

although it is, most often, carried out in the opposite, 3' to 5'

direction. Currently, the process is implemented as

solid-phase synthesis using

phosphoramidite method and phosphoramidite building blocks derived from protected

2'-deoxynucleosides (

dA,

dC,

dG, and

T),

ribonucleosides (

A,

C,

G, and

U), or chemically modified nucleosides, e.g.

LNA or

BNA.

To obtain the desired oligonucleotide, the building blocks are

sequentially coupled to the growing oligonucleotide chain in the order

required by the sequence of the product (see

Synthetic cycle

below). The process has been fully automated since the late 1970s. Upon

the completion of the chain assembly, the product is released from the

solid phase to solution, deprotected, and collected. The occurrence of

side reactions sets practical limits for the length of synthetic

oligonucleotides (up to about 200

nucleotide residues) because the number of errors accumulates with the length of the oligonucleotide being synthesized.

[1] Products are often isolated by

high-performance liquid chromatography

(HPLC) to obtain the desired oligonucleotides in high purity.

Typically, synthetic oligonucleotides are single-stranded DNA or RNA

molecules around 15–25 bases in length.

Oligonucleotides find a variety of applications in molecular biology and medicine. They are most commonly used as

antisense oligonucleotides,

small interfering RNA,

primers for

DNA sequencing and

amplification,

probes for detecting complementary DNA or RNA via molecular

hybridization, tools for the targeted introduction of

mutations and

restriction sites, and for the

synthesis of artificial genes.

History

The

evolution of oligonucleotide synthesis saw four major methods of the

formation of internucleosidic linkages and has been reviewed in the

literature in great detail.

Early work and contemporary H-phosphonate synthesis

Scheme. 1. i: N-Chlorosuccinimide; Bn = -CH2Ph

In the early 1950s,

Alexander Todd’s group pioneered H-phosphonate and

phosphate triester methods of oligonucleotide synthesis. The reaction of compounds

1 and

2 to form H-phosphonate diester

3 is an H-phosphonate coupling in solution while that of compounds

4 and

5 to give

6 is a phosphotriester coupling (see phosphotriester synthesis below).

Scheme 2. Oligonucleotide sythesis by the H-Phosphonate Method

Thirty years later, this work inspired, independently, two research

groups to adopt the H-phosphonate chemistry to the solid-phase synthesis

using nucleoside H-phosphonate monoesters

7 as building blocks

and pivaloyl chloride, 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl chloride

(TPS-Cl), and other compounds as activators.

The practical implementation of H-phosphonate method resulted in a

very short and simple synthetic cycle consisting of only two steps,

detritylation and coupling (Scheme 2).

Oxidation of internucleosidic H-phosphonate diester linkages in

8 to phosphodiester linkages in

9 with a solution of

iodine in aqueous

pyridine

is carried out at the end of the chain assembly rather than as a step

in the synthetic cycle. If desired, the oxidation may be carried out

under anhydrous conditions. Alternatively,

8 can be converted to phosphorothioate

10 or phosphoroselenoate

11 (X = Se), or oxidized by

CCl4 in the presence of primary or secondary amines to phosphoramidate analogs

12.

The method is very convenient in that various types of phosphate

modifications (phosphate/phosphorothioate/phosphoramidate) may be

introduced to the same oligonucleotide for modulation of its properties.

Most often, H-phosphonate building blocks are protected at the

5'-hydroxy group and at the amino group of nucleic bases A, C, and G in

the same manner as phosphoramidite building blocks (see below). However,

protection at the amino group is not mandatory.

Phosphodiester synthesis

Scheme. 3 Oligonucleotide coupling by phosphodiester method; Tr = -CPh3

In the 1950s,

Har Gobind Khorana and co-workers developed a

phosphodiester method where 3’-

O-acetylnucleoside-5’-

O-phosphate

2 (Scheme 3) was activated with

N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) or

4-toluenesulfonyl chloride (Ts-Cl). The activated species were reacted with a 5’-

O-protected nucleoside

1 to give a protected dinucleoside monophosphate

3. Upon the removal of 3’-

O-acetyl

group using base-catalyzed hydrolysis, further chain elongation was

carried out. Following this methodology, sets of tri- and

tetradeoxyribonucleotides were synthesized and were enzymatically

converted to longer oligonucleotides, which allowed elucidation of the

genetic code.

The major limitation of the phosphodiester method consisted in the

formation of pyrophosphate oligomers and oligonucleotides branched at

the internucleosidic phosphate. The method seems to be a step back from

the more selective chemistry described earlier; however, at that time,

most phosphate-protecting groups available now had not yet been

introduced. The lack of the convenient protection strategy necessitated

taking a retreat to a slower and less selective chemistry to achieve the

ultimate goal of the study.

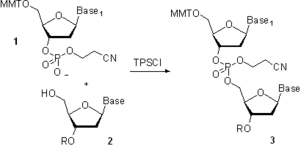

Phosphotriester synthesis

Scheme 4. Oligonucleotide coupling by phosphotriester method; MMT = -CPh2(4-MeOC6H4).

In the 1960s, groups led by R. Letsinger and C. Reese

developed a phosphotriester approach. The defining difference from the

phosphodiester approach was the protection of the phosphate moiety in

the building block

1 (Scheme 4) and in the product

3 with

2-cyanoethyl

group. This precluded the formation of oligonucleotides branched at the

internucleosidic phosphate. The higher selectivity of the method

allowed the use of more efficient coupling agents and catalysts,

which dramatically reduced the length of the synthesis. The method,

initially developed for the solution-phase synthesis, was also

implemented on low-cross-linked "popcorn" polystyrene,

and later on controlled pore glass (CPG, see "Solid support material"

below), which initiated a massive research effort in solid-phase

synthesis of oligonucleotides and eventually led to the automation of

the oligonucleotide chain assembly.

Phosphite triester synthesis

In the 1970s, substantially more reactive P(III) derivatives of nucleosides, 3'-

O-chlorophosphites, were successfully used for the formation of internucleosidic linkages. This led to the discovery of the

phosphite triester methodology. The group led by M. Caruthers took the advantage of less aggressive and more selective 1

H-tetrazolidophosphites and implemented the method on solid phase.

Very shortly after, the workers from the same group further improved

the method by using more stable nucleoside phosphoramidites as building

blocks. The use of 2-cyanoethyl phosphite-protecting group in place of a less user-friendly

methyl group

led to the nucleoside phosphoramidites currently used in

oligonucleotide synthesis (see Phosphoramidite building blocks below).

Many later improvements to the manufacturing of building blocks,

oligonucleotide synthesizers, and synthetic protocols made the

phosphoramidite chemistry a very reliable and expedient method of choice

for the preparation of synthetic oligonucleotides.

Synthesis by the phosphoramidite method

Building blocks

Nucleoside phosphoramidites

Protected 2'-deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites.

As mentioned above, the naturally occurring nucleotides

(nucleoside-3'- or 5'-phosphates) and their phosphodiester analogs are

insufficiently reactive to afford an expeditious synthetic preparation

of oligonucleotides in high yields. The selectivity and the rate of the

formation of internucleosidic linkages is dramatically improved by using

3'-

O-(

N,

N-diisopropyl phosphoramidite) derivatives

of nucleosides (nucleoside phosphoramidites) that serve as building

blocks in phosphite triester methodology. To prevent undesired side

reactions, all other functional groups present in nucleosides have to be

rendered unreactive (protected) by attaching

protecting groups.

Upon the completion of the oligonucleotide chain assembly, all the

protecting groups are removed to yield the desired oligonucleotides.

Below, the protecting groups currently used in commercially available and most common nucleoside phosphoramidite building blocks are briefly reviewed:

- The 5'-hydroxyl group is protected by an acid-labile DMT (4,4'-dimethoxytrityl) group.

- Thymine and uracil, nucleic bases of thymidine and uridine, respectively, do not have exocyclic amino groups and hence do not require any protection.

- Although the nucleic base of guanosine and 2'-deoxyguanosine does have an exocyclic amino group, its basicity

is low to an extent that it does not react with phosphoramidites under

the conditions of the coupling reaction. However, a phosphoramidite

derived from the N2-unprotected 5'-O-DMT-2'-deoxyguanosine is poorly soluble in acetonitrile, the solvent commonly used in oligonucleotide synthesis.

In contrast, the N2-protected versions of the same compound dissolve in

acetonitrile well and hence are widely used. Nucleic bases adenine and cytosine

bear the exocyclic amino groups reactive with the activated

phosphoramidites under the conditions of the coupling reaction. By the

use of additional steps in the synthetic cycle or alternative coupling agents and solvent systems,

the oligonucleotide chain assembly may be carried out using dA and dC

phosphoramidites with unprotected amino groups. However, these

approaches currently remain in the research stage. In routine

oligonucleotide synthesis, exocyclic amino groups in nucleosides are

kept permanently protected over the entire length of the oligonucleotide

chain assembly.

The protection of the exocyclic amino groups has to be orthogonal to

that of the 5'-hydroxy group because the latter is removed at the end of

each synthetic cycle. The simplest to implement, and hence the most

widely used, strategy is to install a base-labile protection group on

the exocyclic amino groups. Most often, two protection schemes are used.

- In the first, the standard and more robust scheme (Figure), Bz (benzoyl) protection is used for A, dA, C, and dC, while G and dG are protected with isobutyryl group. More recently, Ac (acetyl) group is used to protect C and dC as shown in Figure.

- In the second, mild protection scheme, A and dA are protected with isobutyryl or phenoxyacetyl groups (PAC). C and dC bear acetyl protection, and G and dG are protected with 4-isopropylphenoxyacetyl (iPr-PAC) or dimethylformamidino (dmf)

groups. Mild protecting groups are removed more readily than the

standard protecting groups. However, the phosphoramidites bearing these

groups are less stable when stored in solution.

- The phosphite group is protected by a base-labile 2-cyanoethyl group.

Once a phosphoramidite has been coupled to the solid support-bound

oligonucleotide and the phosphite moieties have been converted to the

P(V) species, the presence of the phosphate protection is not mandatory

for the successful conducting of further coupling reactions.

2'-O-protected ribonucleoside phosphoramidites.

- In RNA synthesis, the 2'-hydroxy group is protected with TBDMS (t-butyldimethylsilyl) group. or with TOM (tri-iso-propylsilyloxymethyl) group, both being removable by treatment with fluoride ion.

- The phosphite moiety also bears a diisopropylamino (iPr2N)

group reactive under acidic conditions. Upon activation, the

diisopropylamino group leaves to be substituted by the 5'-hydroxy group

of the support-bound oligonucleotide (see "Step 2: Coupling" below).

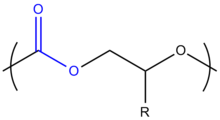

Non-nucleoside phosphoramidites

Non-nucleoside

phosphoramidites for 5'-modification of synthetic oligonucleotides. MMT

= mono-methoxytrityl,

(4-methoxyphenyl)diphenylmethyl.

Non-nucleoside

phosphoramidites are the phosphoramidite reagents designed to introduce

various functionalities at the termini of synthetic oligonucleotides or

between nucleotide residues in the middle of the sequence. In order to

be introduced inside the sequence, a non-nucleosidic modifier has to

possess at least two hydroxy groups, one of which is often protected

with the DMT group while the other bears the reactive phosphoramidite

moiety.

Non-nucleosidic phosphoramidites are used to introduce desired

groups that are not available in natural nucleosides or that can be

introduced more readily using simpler chemical designs. A very short

selection of commercial phosphoramidite reagents is shown in Scheme for

the demonstration of the available structural and functional diversity.

These reagents serve for the attachment of 5'-terminal phosphate (

1), NH

2 (

2), SH (

3), aldehydo (

4), and carboxylic groups (

5), CC triple bonds (

6), non-radioactive labels and

quenchers (exemplified by

6-FAM amidite 7 for the attachment of

fluorescein and dabcyl amidite

8, respectively), hydrophilic and hydrophobic modifiers (exemplified by

hexaethyleneglycol amidite

9 and

cholesterol amidite

10, respectively), and

biotin amidite

11.

Synthetic cycle

Scheme 5. Synthetic cycle for preparation of oligonucleotides by phosphoramidite method.

Oligonucleotide synthesis is carried out by a stepwise addition of

nucleotide residues to the 5'-terminus of the growing chain until the

desired sequence is assembled. Each addition is referred to as a

synthetic cycle (Scheme 5) and consists of four chemical reactions:

Step 1: De-blocking (detritylation)

The DMT group is removed with a solution of an acid, such as 2%

trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or 3%

dichloroacetic acid (DCA), in an inert solvent (

dichloromethane or

toluene).

The orange-colored DMT cation formed is washed out; the step results in

the solid support-bound oligonucleotide precursor bearing a free

5'-terminal hydroxyl group.

It is worth remembering that conducting detritylation for an extended

time or with stronger than recommended solutions of acids leads to

depurination of solid support-bound oligonucleotide and thus reduces the yield of the desired full-length product.

Step 2: Coupling

A 0.02–0.2 M solution of nucleoside phosphoramidite (or a mixture of several phosphoramidites) in

acetonitrile is activated by a 0.2–0.7 M solution of an acidic

azole catalyst,

1H-tetrazole, 5-ethylthio-1H-tetrazole, 2-benzylthiotetrazole, 4,5-dicyano

imidazole,

or a number of similar compounds. A more extensive information on the

use of various coupling agents in oligonucleotide synthesis can be found

in a recent review.

The mixing is usually very brief and occurs in fluid lines of

oligonucleotide synthesizers (see below) while the components are being

delivered to the reactors containing solid support. The activated

phosphoramidite in 1.5 – 20-fold excess over the support-bound material

is then brought in contact with the starting solid support (first

coupling) or a support-bound oligonucleotide precursor (following

couplings) whose 5'-hydroxy group reacts with the activated

phosphoramidite moiety of the incoming nucleoside phosphoramidite to

form a phosphite triester linkage. The coupling of 2'-deoxynucleoside

phosphoramidites is very rapid and requires, on small scale, about 20 s

for its completion. In contrast, sterically hindered 2'-

O-protected ribonucleoside phosphoramidites require 5-15 min to be coupled in high yields.

The reaction is also highly sensitive to the presence of water,

particularly when dilute solutions of phosphoramidites are used, and is

commonly carried out in anhydrous acetonitrile. Generally, the larger

the scale of the synthesis, the lower the excess and the higher the

concentration of the phosphoramidites is used. In contrast, the

concentration of the activator is primarily determined by its solubility

in acetonitrile and is irrespective of the scale of the synthesis. Upon

the completion of the coupling, any unbound reagents and by-products

are removed by washing.

Step 3: Capping

The capping step is performed by treating the solid support-bound material with a mixture of acetic anhydride and

1-methylimidazole or, less often,

DMAP as catalysts and, in the phosphoramidite method, serves two purposes.

- After the completion of the coupling reaction, a small

percentage of the solid support-bound 5'-OH groups (0.1 to 1%) remains

unreacted and needs to be permanently blocked from further chain

elongation to prevent the formation of oligonucleotides with an internal

base deletion commonly referred to as (n-1) shortmers. The unreacted

5'-hydroxy groups are, to a large extent, acetylated by the capping

mixture.

- It has also been reported that phosphoramidites activated with 1H-tetrazole react, to a small extent, with the O6 position of guanosine. Upon oxidation with I2 /water, this side product, possibly via O6-N7 migration, undergoes depurination. The apurinic sites

thus formed are readily cleaved in the course of the final deprotection

of the oligonucleotide under the basic conditions (see below) to give

two shorter oligonucleotides thus reducing the yield of the full-length

product. The O6 modifications are rapidly removed by treatment with the capping reagent as long as the capping step is performed prior to oxidation with I2/water.

- The synthesis of oligonucleotide phosphorothioates (OPS, see below) does not involve the oxidation with I2/water,

and, respectively, does not suffer from the side reaction described

above. On the other hand, if the capping step is performed prior to

sulfurization, the solid support may contain the residual acetic

anhydride and N-methylimidazole left after the capping step. The capping

mixture interferes with the sulfur transfer reaction, which results in

the extensive formation of the phosphate triester internucleosidic

linkages in place of the desired PS triesters. Therefore, for the

synthesis of OPS, it is advisable to conduct the sulfurization step prior to the capping step.

Step 4: Oxidation

The

newly formed tricoordinated phosphite triester linkage is not natural

and is of limited stability under the conditions of oligonucleotide

synthesis. The treatment of the support-bound material with iodine and

water in the presence of a weak base (pyridine,

lutidine, or

collidine)

oxidizes

the phosphite triester into a tetracoordinated phosphate triester, a

protected precursor of the naturally occurring phosphate diester

internucleosidic linkage. Oxidation may be carried out under anhydrous

conditions using

tert-Butyl hydroperoxide or, more efficiently, (1S)-(+)-(10-camphorsulfonyl)-oxaziridine (CSO). The step of oxidation may be substituted with a sulfurization step to obtain oligonucleotide phosphorothioates (see

Oligonucleotide phosphorothioates and their synthesis below). In the latter case, the sulfurization step is best carried out prior to capping.

Solid supports

In solid-phase synthesis, an oligonucleotide being assembled is

covalently

bound, via its 3'-terminal hydroxy group, to a solid support material

and remains attached to it over the entire course of the chain assembly.

The solid support is contained in columns whose dimensions depend on

the scale of synthesis and may vary between 0.05

mL and several liters. The overwhelming majority of oligonucleotides are synthesized on small scale ranging from 10 n

mol

to 1 μmol. More recently, high-throughput oligonucleotide synthesis

where the solid support is contained in the wells of multi-well plates

(most often, 96 or 384 wells per plate) became a method of choice for

parallel synthesis of oligonucleotides on small scale.

At the end of the chain assembly, the oligonucleotide is released from

the solid support and is eluted from the column or the well.

Solid support material

In contrast to organic solid-phase synthesis and

peptide synthesis,

the synthesis of oligonucleotides proceeds best on non-swellable or

low-swellable solid supports. The two most often used solid-phase

materials are controlled pore glass (CPG) and macroporous

polystyrene (MPPS).

- CPG is commonly defined by its pore size. In oligonucleotide chemistry, pore sizes of 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, and 3000 Å

are used to allow the preparation of about 50, 80, 100, 150, and

200-mer oligonucleotides, respectively. To make native CPG suitable for

further processing, the surface of the material is treated with

(3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane to give aminopropyl CPG. The aminopropyl

arm may be further extended to result in long chain aminoalkyl (LCAA)

CPG. The amino group is then used as an anchoring point for linkers

suitable for oligonucleotide synthesis (see below).

- MPPS suitable for oligonucleotide synthesis is a low-swellable, highly cross-linked polystyrene obtained by polymerization of divinylbenzene (min 60%), styrene, and 4-chloromethylstyrene in the presence of a porogeneous agent. The macroporous chloromethyl MPPS obtained is converted to aminomethyl MPPS.

Linker chemistry

Commercial solid supports for oligonucleotide synthesis.

Scheme 6. Mechanism of 3'-dephosphorylation of oligonucleotides assembled on universal solid supports.

To make the solid support material suitable for oligonucleotide

synthesis, non-nucleosidic linkers or nucleoside succinates are

covalently attached to the reactive amino groups in aminopropyl CPG,

LCAA CPG, or aminomethyl MPPS. The remaining unreacted amino groups are

capped with

acetic anhydride. Typically, three conceptually different groups of solid supports are used.

- Universal supports. In a more recent, more convenient,

and more widely used method, the synthesis starts with the universal

support where a non-nucleosidic linker is attached to the solid support

material (compounds 1 and 2). A phosphoramidite respective

to the 3'-terminal nucleoside residue is coupled to the universal solid

support in the first synthetic cycle of oligonucleotide chain assembly

using the standard protocols. The chain assembly is then continued until

the completion, after which the solid support-bound oligonucleotide is

deprotected. The characteristic feature of the universal solid supports

is that the release of the oligonucleotides occurs by the hydrolytic

cleavage of a P-O bond that attaches the 3’-O of the 3’-terminal

nucleotide residue to the universal linker as shown in Scheme 6. The

critical advantage of this approach is that the same solid support is

used irrespectively of the sequence of the oligonucleotide to be

synthesized. For the complete removal of the linker and the 3'-terminal

phosphate from the assembled oligonucleotide, the solid support 1 and several similar solid supports require gaseous ammonia, aqueous ammonium hydroxide, aqueous methylamine, or their mixture and are commercially available. The solid support 2 requires a solution of ammonia in anhydrous methanol and is also commercially available.

- Nucleosidic solid supports. In a historically first and still

popular approach, the 3'-hydroxy group of the 3'-terminal nucleoside

residue is attached to the solid support via, most often, 3’-O-succinyl arm as in compound 3. The oligonucleotide chain assembly starts with the coupling of a phosphoramidite building block respective to the nucleotide

residue second from the 3’-terminus. The 3’-terminal hydroxy group in

oligonucleotides synthesized on nucleosidic solid supports is

deprotected under the conditions somewhat milder than those applicable

for universal solid supports. However, the fact that a nucleosidic solid

support has to be selected in a sequence-specific manner reduces the

throughput of the entire synthetic process and increases the likelihood

of human error.

- Special solid supports are used for the attachment of desired

functional or reporter groups at the 3’-terminus of synthetic

oligonucleotides. For example, the commercial solid support 4

allows the preparation of oligonucleotides bearing 3’-terminal

3-aminopropyl linker. Similarly to non-nucleosidic phosphoramidites,

many other special solid supports designed for the attachment of

reactive functional groups, non-radioactive reporter groups, and

terminal modifiers (e.c. cholesterol

or other hydrophobic tethers) and suited for various applications are

commercially available. A more detailed information on various solid

supports for oligonucleotide synthesis can be found in a recent review.

Oligonucleotide phosphorothioates and their synthesis

Sp and Rp-diastereomeric internucleosidic phosphorothioate linkages.

Oligonucleotide phosphorothioates (OPS) are modified oligonucleotides

where one of the oxygen atoms in the phosphate moiety is replaced by

sulfur. Only the phosphorothioates having sulfur at a non-bridging

position as shown in figure are widely used and are available

commercially. The replacement of the non-bridging oxygen with sulfur

creates a new center of

chirality at

phosphorus. In a simple case of a dinucleotide, this results in the formation of a

diastereomeric pair of S

p- and R

p-dinucleoside monophosphorothioates whose structures are shown in Figure. In an

n-mer oligonucleotide where all (

n – 1) internucleosidic linkages are phosphorothioate linkages, the number of diastereomers

m is calculated as

m = 2

(n – 1). Being non-natural analogs of nucleic acids, OPS are substantially more stable towards

hydrolysis by

nucleases, the class of

enzymes

that destroy nucleic acids by breaking the bridging P-O bond of the

phosphodiester moiety. This property determines the use of OPS as

antisense oligonucleotides in

in vitro and

in vivo applications where the extensive exposure to nucleases is inevitable. Similarly, to improve the stability of

siRNA, at least one phosphorothioate linkage is often introduced at the 3'-terminus of both

sense

and antisense strands. In chirally pure OPS, all-Sp diastereomers are

more stable to enzymatic degradation than their all-Rp analogs. However, the preparation of chirally pure OPS remains a synthetic challenge. In laboratory practice, mixtures of diastereomers of OPS are commonly used.

Synthesis of OPS is very

similar to that of natural oligonucleotides. The difference is that the

oxidation step is replaced by sulfur transfer reaction (sulfurization)

and that the capping step is performed after the sulfurization. Of many

reported reagents capable of the efficient sulfur transfer, only three

are commercially available:

Commercial sulfur transfer agents for oligonucleotide synthesis.

- 3-(Dimethylaminomethylidene)amino-3H-1,2,4-dithiazole-3-thione, DDTT (3) provides rapid kinetics of sulfurization and high stability in solution. The reagent is available from several sources.

- 3H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one 1,1-dioxide (4)

also known as Beaucage reagent displays a better solubility in

acetonitrile and short reaction times. However, the reagent is of

limited stability in solution and is less efficient in sulfurizing RNA

linkages.

- N,N,N'N'-Tetraethylthiuram disulfide (TETD) is soluble in acetonitrile and is commercially available. However, the sulfurization reaction of an internucleosidic DNA linkage with TETD requires 15 min, which is more than 10 times as slow as that with compounds 3 and 4.

Automation

In

the past, oligonucleotide synthesis was carried out manually in

solution or on solid phase. The solid phase synthesis was implemented

using, as containers for the solid phase, miniature glass columns

similar in their shape to low-pressure chromatography columns or

syringes equipped with porous filters.

Currently, solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis is carried out

automatically using computer-controlled instruments (oligonucleotide

synthesizers) and is technically implemented in column, multi-well

plate, and array formats. The column format is best suited for research

and large scale applications where a high-throughput is not required.

Multi-well plate format is designed specifically for high-throughput

synthesis on small scale to satisfy the growing demand of industry and

academia for synthetic oligonucleotides. A number of oligonucleotide synthesizers for small scale synthesis and medium to large scale synthesis are available commercially.

First commercially available oligonucleotide synthesizers

In

March 1982 a practical course was hosted by the Department of

Biochemistry, Technische Hochschule Darmstadt, Germany. M.H. Caruthers,

M.J. Gait, H.G. Gassen, H.Koster, K. Itakura, and C. Birr among others

attended. The program comprised practical work, lectures, and seminars

on solid-phase chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides. A select group of

15 students attended and had an unprecedented opportunity to be

instructed by the esteemed teaching staff.

Along

with manual exercises, several prominent automation companies attended

the course. Biosearch of Novato, CA, Genetic Design of Watertown, MA,

were two of several companies to demonstrate automated synthesizers at

the course. Biosearch presented their new SAM I synthesizer. The Genetic

Design had developed their synthesizer from the design of its sister

companies (Sequemat) solid phase peptide sequencer. The Genetic Design

arranged with Dr Christian Birr (Max-Planck-Institute for Medical

Research)

a week before the event to convert his solid phase sequencer into the

semi-automated synthesizer. The team led by Dr Alex Bonner and Rick

Neves converted the unit and transported it to Darmstadt for the event

and installed into the Biochemistry lab at the Technische Hochschule. As

the system was semi-automatic, the user injected the next base to be

added to the growing sequence during each cycle. The system worked well

and produced a series of test tubes filled with bright red trityl color

indicating complete coupling at each step. This system was later fully

automated by inclusion of an auto injector and was designated the Model

25A.

History of mid to large scale oligonucleotide synthesis

Large

scale oligonucleotide synthesizers were often developed by augmenting

the capabilities of a preexisting instrument platform. One of the first

mid scale synthesizers appeared in the late 1980s, manufactured by the

Biosearch company in Novato, CA (The 8800). This platform was originally

designed as a peptide synthesizer and made use of a fluidized bed

reactor essential for accommodating the swelling characteristics of

polystyrene supports used in the Merrifield methodology. Oligonucleotide

synthesis involved the use of CPG (controlled pore glass) which is a

rigid support and is more suited for column reactors as described above.

The scale of the 8800 was limited to the flow rate required to fluidize

the support. Some novel reactor designs as well as higher than normal

pressures enabled the 8800 to achieve scales that would prepare 1 mmole

of oligonucleotide. In the mid 1990s several companies developed

platforms that were based on semi-preparative and preparative liquid

chromatographs. These systems were well suited for a column reactor

approach. In most cases all that was required was to augment the number

of fluids that could be delivered to the column. Oligo synthesis

requires a minimum of 10 and liquid chromatographs usually accommodate

4. This was an easy design task and some semi-automatic strategies

worked without any modifications to the preexisting LC equipment.

PerSeptive Biosystems as well as Pharmacia (GE) were two of several

companies that developed synthesizers out of liquid chromatographs.

Genomic Technologies, Inc.

was one of the few companies to develop a large scale oligonucleotide

synthesizer that was, from the ground up, an oligonucleotide

synthesizer. The initial platform called the VLSS for very large scale

synthesizer utilized large Pharmacia liquid chromatograph columns as

reactors and could synthesize up to 75 millimoles of material. Many

oligonucleotide synthesis factories designed and manufactured their own

custom platforms and little is known due to the designs being

proprietary. The VLSS design continued to be refined and is continued in

the QMaster synthesizer which is a scaled down platform providing milligram to gram amounts of synthetic oligonucleotide.

The current practices of synthesis of chemically modified oligonucleotides on large scale have been recently reviewed.

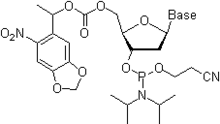

Synthesis of oligonucleotide microarrays

One may visualize an oligonucleotide microarray as a miniature

multi-well plate where physical dividers between the wells (plastic

walls) are intentionally removed. With respect to the chemistry,

synthesis of oligonucleotide microarrays is different from the

conventional oligonucleotide synthesis in two respects:

5'-O-MeNPOC-protected nucleoside phosphoramidite.

- Oligonucleotides remain permanently attached to the solid phase,

which requires the use of linkers that are stable under the conditions

of the final deprotection procedure.

- The absence of physical dividers between the sites occupied by

individual oligonucleotides, a very limited space on the surface of the

microarray (one oligonucleotide sequence occupies a square 25×25 μm)

and the requirement of high fidelity of oligonucleotide synthesis

dictate the use of site-selective 5'-deprotection techniques. In one

approach, the removal of the 5'-O-DMT group is effected by electrochemical generation of the acid at the required site(s). Another approach uses 5'-O-(α-methyl-6-nitropiperonyloxycarbonyl)

(MeNPOC) protecting group, which can be removed by irradiation with UV

light of 365 nm wavelength.

Post-synthetic processing

After the completion of the chain assembly, the solid support-bound oligonucleotide is fully protected:

- The 5'-terminal 5'-hydroxy group is protected with DMT group;

- The internucleosidic phosphate or phosphorothioate moieties are protected with 2-cyanoethyl groups;

- The exocyclic amino groups in all nucleic bases except for T and U are protected with acyl protecting groups.

To furnish a functional oligonucleotide, all the protecting groups

have to be removed. The N-acyl base protection and the 2-cyanoethyl

phosphate protection may be, and is often removed simultaneously by

treatment with inorganic bases or amines. However, the applicability of

this method is limited by the fact that the cleavage of 2-cyanoethyl

phosphate protection gives rise to

acrylonitrile

as a side product. Under the strong basic conditions required for the

removal of N-acyl protection, acrylonitrile is capable of alkylation of

nucleic bases, primarily, at the N3-position of thymine and uracil

residues to give the respective N3-(2-cyanoethyl) adducts via

Michael reaction. The formation of these side products may be avoided by treating the

solid support-bound oligonucleotides with solutions of bases in an

organic solvent, for instance, with 50%

triethylamine in

acetonitrile or 10%

diethylamine in acetonitrile.

This treatment is strongly recommended for medium- and large scale

preparations and is optional for syntheses on small scale where the

concentration of acrylonitrile generated in the deprotection mixture is

low.

Regardless of whether the phosphate protecting groups were

removed first, the solid support-bound oligonucleotides are deprotected

using one of the two general approaches.

- (1) Most often, 5'-DMT group is removed at the end of the

oligonucleotide chain assembly. The oligonucleotides are then released

from the solid phase and deprotected (base and phosphate) by treatment

with aqueous ammonium hydroxide, aqueous methylamine, their mixtures, gaseous ammonia or methylamine

or, less commonly, solutions of other primary amines or alkalies at

ambient or elevated temperature. This removes all remaining protection

groups from 2'-deoxyoligonucleotides, resulting in a reaction mixture

containing the desired product. If the oligonucleotide contains any 2'-O-protected ribonucleotide residues, the deprotection protocol includes the second step where the 2'-O-protecting silyl groups are removed by treatment with fluoride ion by various methods.

The fully deprotected product is used as is, or the desired

oligonucleotide can be purified by a number of methods. Most commonly,

the crude product is desalted using ethanol precipitation, size exclusion chromatography, or reverse-phase HPLC. To eliminate unwanted truncation products, the oligonucleotides can be purified via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or anion-exchange HPLC followed by desalting.

- (2) The second approach is only used when the intended method of purification is reverse-phase HPLC.

In this case, the 5'-terminal DMT group that serves as a hydrophobic

handle for purification is kept on at the end of the synthesis. The

oligonucleotide is deprotected under basic conditions as described above

and, upon evaporation, is purified by reverse-phase HPLC. The collected

material is then detritylated under aqueous acidic conditions. On small

scale (less than 0.01–0.02 mmol), the treatment with 80% aqueous acetic

acid for 15–30 min at room temperature is often used followed by

evaporation of the reaction mixture to dryness in vacuo. Finally, the product is desalted as described above.

- For some applications, additional reporter groups may be attached to

an oligonucleotide using a variety of post-synthetic procedures.

Characterization

Deconvoluted ES MS of crude oligonucleotide 5'-DMT-T20

(calculated mass 6324.26 Da).

As with any other organic compound, it is prudent to characterize

synthetic oligonucleotides upon their preparation. In more complex cases

(research and large scale syntheses) oligonucleotides are characterized

after their deprotection and after purification. Although the ultimate

approach to the characterization is

sequencing,

a relatively inexpensive and routine procedure, the considerations of

the cost reduction preclude its use in routine manufacturing of

oligonucleotides. In day-by-day practice, it is sufficient to obtain the

molecular mass of an oligonucleotide by recording its

mass spectrum. Two methods are currently widely used for characterization of oligonucleotides:

electrospray mass spectrometry (ES MS) and

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (

MALDI-TOF).

To obtain informative spectra, it is very important to exchange all

metal ions that might be present in the sample for ammonium or

trialkylammonium [

e.c. triethylammonium, (C

2H

5)

3NH

+] ions prior to submitting a sample to the analysis by either of the methods.

- In ES MS spectrum, a given oligonucleotide generates a set of

ions that correspond to different ionization states of the compound.

Thus, the oligonucleotide with molecular mass M generates ions with masses (M – nH)/n

where M is the molecular mass of the oligonucleotide in the form of a

free acid (all negative charges of internucleosidic phosphodiester

groups are neutralized with H+), n is the ionization state, and H is the atomic mass of hydrogen (1 Da). Most useful for characterization are the ions with n ranging from 2 to 5. Software supplied with the more recently manufactured instruments is capable of performing a deconvolution procedure that is, it finds peaks of ions that belong to the same set and derives the molecular mass of the oligonucleotide.

- To obtain more detailed information on the impurity profile of oligonucleotides, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS or HPLC-MS) or capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry (CEMS) are used.