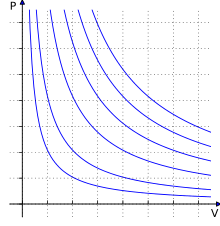

Isotherms of an ideal gas. The curved lines represent the relationship between pressure (on the vertical axis) and volume (on the horizontal axis) for an ideal gas at different temperatures: lines that are farther away from the origin (that is, lines that are nearer to the top right-hand corner of the diagram) represent higher temperatures.

The ideal gas law, also called the general gas equation, is the equation of state of a hypothetical ideal gas. It is a good approximation of the behavior of many gases under many conditions, although it has several limitations. It was first stated by Émile Clapeyron in 1834 as a combination of the empirical Boyle's law, Charles's law, Avogadro's law, and Gay-Lussac's law. The ideal gas law is often written as

Equation

Molecular

collisions within a closed container (the propane tank) are shown

(right). The arrows represent the random motions and collisions of these

molecules. The pressure and temperature of the gas are directly

proportional: as the temperature is increased, the pressure of the

propane increases by the same factor. A simple consequence of this

proportionality is that on a hot summer day, the propane tank pressure

will be elevated, and thus propane tanks must be rated to withstand such

increases in pressure.

The state of an amount of gas is determined by its pressure, volume, and temperature. The modern form of the equation relates these simply in two main forms. The temperature used in the equation of state is an absolute temperature: the appropriate SI unit is the kelvin.

Common forms

The most frequently introduced form is- is the pressure of the gas,

- is the volume of the gas,

- is the amount of substance of gas (also known as number of moles),

- is the number of gas molecules (or the Avogadro constant times the amount of substance ),

- is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

- is the Boltzmann constant,

- is the absolute temperature of the gas.

Molar form

How much gas is present could be specified by giving the mass instead of the chemical amount of gas. Therefore, an alternative form of the ideal gas law may be useful. The chemical amount (n) (in moles) is equal to total mass of the gas (m) (in grams) divided by the molar mass (M) (in grams per mole):- ,

- ,

- .

- .

Statistical mechanics

In statistical mechanics the following molecular equation is derived from first principlesFrom this we notice that for a gas of mass m, with an average particle mass of μ times the atomic mass constant, mu, (i.e., the mass is μ u) the number of molecules will be given by

Energy associated with a gas

According to the assumptions of the kinetic theory of gases, we assumed that there are no intermolecular attractions between the molecules of an ideal gas. In other words, its potential energy is zero. Hence, all the energy possessed by the gas is kinetic energy..

This is the kinetic energy of one mole of a gas.

| Energy of gas | Mathematical formula |

|---|---|

| Energy associated with one mole of a gas | |

| Energy associated with one gram of a gas | |

| Energy associated with one molecule of a gas |

Applications to thermodynamic processes

The table below essentially simplifies the ideal gas equation for a particular processes, thus making this equation easier to solve using numerical methods.A thermodynamic process is defined as a system that moves from state 1 to state 2, where the state number is denoted by subscript. As shown in the first column of the table, basic thermodynamic processes are defined such that one of the gas properties (P, V, T, S, or H) is constant throughout the process.

For a given thermodynamics process, in order to specify the extent of a particular process, one of the properties ratios (which are listed under the column labeled "known ratio") must be specified (either directly or indirectly). Also, the property for which the ratio is known must be distinct from the property held constant in the previous column (otherwise the ratio would be unity, and not enough information would be available to simplify the gas law equation).

In the final three columns, the properties (P, V, or T) at state 2 can be calculated from the properties at state 1 using the equations listed.

| Process | Constant | Known ratio or delta | P2 | V2 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isobaric process | P2 = P1 | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1) | ||

| P2 = P1 | V2 = V1(T2/T1) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | |||

| Isochoric process (Isovolumetric process) (Isometric process) |

P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1 | T2 = T1(P2/P1) | ||

| P2 = P1(T2/T1) | V2 = V1 | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | |||

| Isothermal process | P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1/(P2/P1) | T2 = T1 | ||

| P2 = P1/(V2/V1) | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1 | |||

| Isentropic process (Reversible adiabatic process) |

P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1(P2/P1)(−1/γ) | T2 = T1(P2/P1)(γ − 1)/γ | ||

| P2 = P1(V2/V1)−γ | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1)(1 − γ) | |||

| P2 = P1(T2/T1)γ/(γ − 1) | V2 = V1(T2/T1)1/(1 − γ) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | |||

| Polytropic process | P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1(P2/P1)(-1/n) | T2 = T1(P2/P1)(n − 1)/n | ||

| P2 = P1(V2/V1)−n | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1)(1 − n) | |||

| P2 = P1(T2/T1)n/(n − 1) | V2 = V1(T2/T1)1/(1 − n) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | |||

| Isenthalpic process (Irreversible adiabatic process) |

P2 = P1 + (P2 − P1) |

|

T2 = T1 + μJT(P2 − P1) | ||

| P2 = P1 + (T2 − T1)/μJT |

|

T2 = T1 + (T2 − T1) |

In an isentropic process, system entropy (S) is constant. Under these conditions, P1 V1γ = P2 V2γ, where γ is defined as the heat capacity ratio, which is constant for a calorifically perfect gas. The value used for γ is typically 1.4 for diatomic gases like nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2), (and air, which is 99% diatomic). Also γ is typically 1.6 for mono atomic gases like the noble gases helium (He), and argon (Ar). In internal combustion engines γ varies between 1.35 and 1.15, depending on constitution gases and temperature.

In an isenthalpic process, system enthalpy (H) is constant. In the case of free expansion for an ideal gas, there are no molecular interactions, and the temperature remains constant. For real gasses, the molecules do interact via attraction or repulsion depending on temperature and pressure, and heating or cooling does occur. This is known as the Joule–Thomson effect. For reference, the Joule–Thomson coefficient μJT for air at room temperature and sea level is 0.22 °C/bar.

Deviations from ideal behavior of real gases

The equation of state given here (PV=nRT) applies only to an ideal gas, or as an approximation to a real gas that behaves sufficiently like an ideal gas. There are in fact many different forms of the equation of state. Since the ideal gas law neglects both molecular size and inter molecular attractions, it is most accurate for monatomic gases at high temperatures and low pressures. The neglect of molecular size becomes less important for lower densities, i.e. for larger volumes at lower pressures, because the average distance between adjacent molecules becomes much larger than the molecular size. The relative importance of intermolecular attractions diminishes with increasing thermal kinetic energy, i.e., with increasing temperatures. More detailed equations of state, such as the van der Waals equation, account for deviations from ideality caused by molecular size and intermolecular forces.A residual property is defined as the difference between a real gas property and an ideal gas property, both considered at the same pressure, temperature, and composition.

Derivations

Empirical

The empirical laws that led to the derivation of the ideal gas law were discovered with experiments that changed only 2 state variables of the gas and kept every other one constant.All the possible gas laws that could have been discovered with this kind of setup are:

or (1), known as Boyle´s law,

or (2), known as Charles´s law,

or (3), known as Avogadro´s law,

or (4), known as Gay-Lussac´s law,

or (5),

or (6).

Where "P" stands for pressure, "V" for volume, "N" for number of particles in the gas and "T" for temperature; Where are not actual constants but are in this context because of each equation requiring only the parameters explicitly noted in it changing.

To derive the ideal gas law one does not need to know all 6 formulas, one can just know 3 and with those derive the rest or just one more to be able to get the ideal gas law, which needs 4.

Since each formula only holds when only the state variables involved in said formula change while the others remain constant, we cannot simply use algebra and directly combine them all. I.e. Boyle did his experiments while keeping N and T constant and this must be taken into account.

Keeping this in mind, to carry the derivation on correctly, one must imagine the gas being altered by one process at a time. The derivation using 4 formulas can look as follows:

At first the gas has parameters .

Starting to change only pressure and volume according to Boyle's law (1), then (7). After this process, the gas has parameters .

Using (5) to change the number of particles in the gas and the temperature yields (8). After this process, the gas has parameters .

Using then Eq. (6) to change the pressure and the number of particles yields (9). After this process, the gas has parameters .

Using then Charles´s law to change the volume and temperature of the gas, (10). After this process, the gas has parameters .

Using simple algebra on equations (7), (8), (9) and (10) yields the result:

or , Where stands for Boltzman´s constant.

Another equivalent result, using the fact that ,where "n" is the number of moles in the gas and "R" is the universal gas constant, is:

, which is known as the ideal gas law.

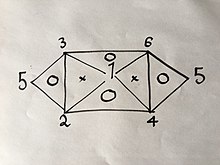

If you know or have found with an experiment 3 of the 6 formulas, you can easily derive the rest using the same method explained above; but due to the properties of said equations, namely that they only have 2 variables in them, they cant be any 3 formulas. For example if you were to have Eqs. (1), (2) and (4) you would not be able to get any more because combining any two of them will give you the third; But if you had Eqs. (1), (2) and (3) you would be able to get all 6 Equations without having to do the rest of the experiments because combining (1) and (2) will yield (4), then (1) and (3) will yield (6), then (4) and (6) will yield (5), as well as would the combination of (2) and (3) as is visually explained in the following visual relation:

Relationship between the 6 gas laws

(The numbers represent the gas laws numbered above.)

If you were to use the same method used above on 2 of the 3 laws on the vertices of one triangle that has a "O" inside it, you would get the third.

For example:

Change only pressure and volume first, (1´), then only volume and temperature, (2´), then as we can choose any value for , if we set , Eq. (2´) becomes(3´).

Combining equations (1´) and (3´) yields , which is Eq. (4), of which we had no prior knowledge until this derivation.

Theoretical

Kinetic theory

The ideal gas law can also be derived from first principles using the kinetic theory of gases, in which several simplifying assumptions are made, chief among which are that the molecules, or atoms, of the gas are point masses, possessing mass but no significant volume, and undergo only elastic collisions with each other and the sides of the container in which both linear momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.Statistical mechanics

Let q = (qx, qy, qz) and p = (px, py, pz) denote the position vector and momentum vector of a particle of an ideal gas, respectively. Let F denote the net force on that particle. Then the time-averaged kinetic energy of the particle is:Putting these equalities together yields

,

, ,

, .

. .

.

.

.

,

,

.

. .

.

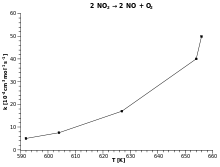

![\ E_{a}\equiv -R\left[{\frac {\partial \ln k}{\partial ~(1/T)}}\right]_{P}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ced30491950c8daf11f19edfb3b96a997db9fe2d) .

. .

.![k=A\exp \left[-\left({\frac {E_{a}}{RT}}\right)^{\beta }\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3f2736359746a38bb3416c9e56a64e256343d656) ,

,

,

,