The problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient God (see theism). An argument from evil

claims that because evil exists, either God does not exist or does not

have all three of those properties. Attempts to show the contrary have

traditionally been discussed under the heading of theodicy. Besides philosophy of religion, the problem of evil is also important to the field of theology and ethics.

The problem of evil is often formulated in two forms: the logical problem of evil and the evidential problem of evil. The logical form of the argument tries to show a logical impossibility in the coexistence of God and evil, while the evidential form tries to show that given the evil in the world, it is improbable that there is an omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good God. The problem of evil has been extended to non-human life forms, to include animal suffering from natural evils and human cruelty against them.

Responses to various versions of the problem of evil, meanwhile, come in three forms: refutations, defenses, and theodicies. A wide range of responses have been made against these arguments. There are also many discussions of evil and associated problems in other philosophical fields, such as secular ethics, and evolutionary ethics. But as usually understood, the "problem of evil" is posed in a theological context.

The problem of evil acutely applies to monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Judaism that believe in a monotheistic God who is omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent; but the question of "why does evil exist?" has also been studied in religions that are non-theistic or polytheistic, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism.

The problem of evil is often formulated in two forms: the logical problem of evil and the evidential problem of evil. The logical form of the argument tries to show a logical impossibility in the coexistence of God and evil, while the evidential form tries to show that given the evil in the world, it is improbable that there is an omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good God. The problem of evil has been extended to non-human life forms, to include animal suffering from natural evils and human cruelty against them.

Responses to various versions of the problem of evil, meanwhile, come in three forms: refutations, defenses, and theodicies. A wide range of responses have been made against these arguments. There are also many discussions of evil and associated problems in other philosophical fields, such as secular ethics, and evolutionary ethics. But as usually understood, the "problem of evil" is posed in a theological context.

The problem of evil acutely applies to monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Judaism that believe in a monotheistic God who is omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent; but the question of "why does evil exist?" has also been studied in religions that are non-theistic or polytheistic, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism.

Formulation and detailed arguments

The problem of evil refers to the challenge of reconciling belief in

an omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent God, with the existence of

evil and suffering in the world. The problem may be described either experientially or theoretically.

The experiential problem is the difficulty in believing in a concept of

a loving God when confronted by suffering or evil in the real world,

such as from epidemics, or wars, or murder, or rape or terror attacks

wherein innocent children, women, men or a loved one becomes a victim.

The problem of evil is also a theoretical one, usually described and

studied by religion scholars in two varieties: the logical problem and

the evidential problem.

Logical problem of evil

Originating with Greek philosopher Epicurus, the logical argument from evil is as follows:

- If an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient god exists, then evil does not.

- There is evil in the world.

- Therefore, an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient god does not exist.

This argument is of the form modus tollens, and is logically valid:

If its premises are true, the conclusion follows of necessity. To show

that the first premise is plausible, subsequent versions tend to expand

on it, such as this modern example:

- God exists.

- God is omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient.

- An omnipotent being has the power to prevent that evil from coming into existence.

- An omnibenevolent being would want to prevent all evils.

- An omniscient being knows every way in which evils can come into existence, and knows every way in which those evils could be prevented.

- A being who knows every way in which an evil can come into existence, who is able to prevent that evil from coming into existence, and who wants to do so, would prevent the existence of that evil.

- If there exists an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient God, then no evil exists.

- Evil exists (logical contradiction).

Both of these arguments are understood to be presenting two forms of the logical problem of evil. They attempt to show that the assumed propositions lead to a logical contradiction

and therefore cannot all be correct. Most philosophical debate has

focused on the propositions stating that God cannot exist with, or would

want to prevent, all evils (premises 3 and 6), with defenders of theism

(for example, Leibniz) arguing that God could very well exist with and

allow evil in order to achieve a greater good.

If God lacks any one of these qualities—omniscience, omnipotence,

or omnibenevolence—then the logical problem of evil can be resolved. Process theology and open theism are other positions that limit God's omnipotence and/or omniscience (as defined in traditional theology). Dystheism is the belief that God is not wholly good.

Evidential problem of evil

William L. Rowe's example of natural evil:

"In some distant forest lightning strikes a dead tree, resulting in a

forest fire. In the fire a fawn is trapped, horribly burned, and lies in

terrible agony for several days before death relieves its suffering." Rowe also cites the example of human evil where an innocent child is a victim of violence and thereby suffers.

The evidential problem of evil (also referred to as the

probabilistic or inductive version of the problem) seeks to show that

the existence of evil, although logically consistent with the existence

of God, counts against or lowers the probability

of the truth of theism. As an example, a critic of Plantinga's idea of

"a mighty nonhuman spirit" causing natural evils may concede that the

existence of such a being is not logically impossible but argue that due

to lacking scientific evidence for its existence this is very unlikely

and thus it is an unconvincing explanation for the presence of natural

evils. Both absolute versions and relative versions of the evidential

problems of evil are presented below.

A version by William L. Rowe:

- There exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- (Therefore) There does not exist an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being.

Another by Paul Draper:

- Gratuitous evils exist.

- The hypothesis of indifference, i.e., that if there are supernatural beings they are indifferent to gratuitous evils, is a better explanation for (1) than theism.

- Therefore, evidence prefers that no god, as commonly understood by theists, exists.

Problem of evil and animal suffering

The problem of evil has also been extended beyond human suffering, to

include suffering of animals from cruelty, disease and evil.

One version of this problem includes animal suffering from natural

evil, such as the violence and fear faced by animals from predators,

natural disasters, over the history of evolution. This is also referred to as the Darwinian problem of evil, after Charles Darwin who expressed it as follows:

'the sufferings of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time' are apparently irreconcilable with the existence of a creator of 'unbounded' goodness.

— Charles Darwin, 1856

The second version of the problem of evil applied to animals, and

avoidable suffering experienced by them, is one caused by some human

beings, such as from animal cruelty or when they are shot or

slaughtered. This version of the problem of evil has been used by

scholars including John Hick

to counter the responses and defenses to the problem of evil such as

suffering being a means to perfect the morals and greater good because

animals are innocent, helpless, amoral but sentient victims. Scholar Michael Almeida said this was "perhaps the most serious and difficult" version of the problem of evil. The problem of evil in the context of animal suffering, states Almeida, can be stated as:

- God is omnipotent, omniscient and wholly good.

- The evil of extensive animal suffering exists.

- Necessarily, God can actualize an evolutionary perfect world.

- Necessarily, God can actualize an evolutionary perfect world only if God does actualize an evolutionary perfect world.

- Necessarily, God actualized an evolutionary perfect world.

- If #1 is true then either #2 or #5 is true, but not both. This is a contradiction, so #1 is not true.

Responses, defences and theodicies

Responses to the problem of evil have occasionally been classified as defences or theodicies; however, authors disagree on the exact definitions. Generally, a defense

against the problem of evil may refer to attempts to defuse the logical

problem of evil by showing that there is no logical incompatibility

between the existence of evil and the existence of God. This task does

not require the identification of a plausible explanation of evil, and

is successful if the explanation provided shows that the existence of

God and the existence of evil are logically compatible. It need not even

be true, since a false though coherent explanation would be sufficient

to show logical compatibility.

A theodicy,

on the other hand, is more ambitious, since it attempts to provide a

plausible justification—a morally or philosophically sufficient

reason—for the existence of evil and thereby rebut the "evidential"

argument from evil. Richard Swinburne

maintains that it does not make sense to assume there are greater goods

that justify the evil's presence in the world unless we know what they

are—without knowledge of what the greater goods could be, one cannot

have a successful theodicy. Thus, some authors see arguments appealing to demons or the fall of man as indeed logically possible, but not very plausible given our knowledge about the world, and so see those arguments as providing defenses but not good theodicies.

The above argument is set against numerous versions of the problem of evil that have been formulated. These versions have included philosophical and theological formulations.

Skeptical theism

Skeptical theism defends the problem of evil by asserting that God

allows an evil to happen in order to prevent a greater evil or to

encourage a response that will lead to a greater good.

Thus a rape or a murder of an innocent child is defended as having a

God's purpose that a human being may not comprehend, but which may lead

to lesser evil or greater good.

This is called skeptical theism because the argument aims to encourage

self-skepticism, either by trying to rationalize God's possible hidden

motives, or by trying to explain it as a limitation of human ability to

know.

The greater good defense is more often argued in religious studies in

response to the evidential version of the problem of evil, while the free will defense is usually discussed in the context of the logical version.

Most scholars criticize the skeptical theism defense as "devaluing the

suffering" and not addressing the premise that God is all-benevolent and

should be able to stop all suffering and evil, rather than play a

balancing act.

"Greater good" responses

The omnipotence paradoxes,

where evil persists in the presence of an all powerful God, raise

questions as to the nature of God's omnipotence. There is the further

question of how an interference would negate and subjugate the concept

of free will, or in other words result in a totalitarian system that

creates a lack of freedom. Some solutions propose that omnipotence does

not require the ability to actualize the logically impossible. "Greater

good" responses to the problem make use of this insight by arguing for

the existence of goods of great value which God cannot actualize without

also permitting evil, and thus that there are evils he cannot be

expected to prevent despite being omnipotent. Among the most popular

versions of the "greater good" response are appeals to the apologetics

of free will. Theologians will argue that since no one can fully

understand God's ultimate plan, no one can assume that evil actions do

not have some sort of greater purpose. Therefore, they say nature of

evil has a necessary role to play in God's plan for a better world.

Free will

The problem of evil is sometimes explained as a consequence of free will, an ability granted by God.

Free will is both a source of good and of evil, and with free will also

comes the potential for abuse, as when individuals act immorally.

People with free will "decide to cause suffering and act in other evil

ways", states Boyd, and it is they who make that choice, not God.

Further, the free will argument asserts that it would be logically

inconsistent for God to prevent evil by coercion and curtailing free

will, because that would no longer be free will.

Critics of the free will response have questioned whether it

accounts for the degree of evil seen in this world. One point in this

regard is that while the value of free will may be thought sufficient to

counterbalance minor evils, it is less obvious that it outweighs the

negative attributes of evils such as rape and murder. Particularly

egregious cases known as horrendous evils, which "[constitute] prima facie

reason to doubt whether the participant’s life could (given their

inclusion in it) be a great good to him/her on the whole," have been the

focus of recent work in the problem of evil.

Another point is that those actions of free beings which bring about

evil very often diminish the freedom of those who suffer the evil; for

example the murder of a young child prevents the child from ever

exercising their free will. In such a case the freedom of an innocent

child is pitted against the freedom of the evil-doer, it is not clear

why God would remain unresponsive and passive.

Another criticism is that the potential for evil inherent in free

will may be limited by means which do not impinge on that free will.

God could accomplish this by making moral actions especially

pleasurable, or evil action and suffering impossible by allowing free

will but not allowing the ability to enact evil or impose suffering. Supporters of the free will explanation state that that would no longer be free will.

Critics respond that this view seems to imply it would be similarly

wrong to try to reduce suffering and evil in these ways, a position

which few would advocate.

A third challenge to the free will defence is natural evil, which is the result of natural causes (e.g. a child suffering from a disease, mass casualties from a volcano).

The "natural evil" criticism posits that even if for some reason an

all-powerful and all-benevolent God tolerated evil human actions in

order to allow free will, such a God would not be expected to also

tolerate natural evils because they have no apparent connection to free

will.

Advocates of the free will response to evil propose various explanations of natural evils. Alvin Plantinga, following Augustine of Hippo, and others have argued that natural evils are caused by the free choices of supernatural beings such as demons. Others have argued

- • that natural evils are the result of the fall of man, which corrupted the perfect world created by God or

- • that natural evils are the result of natural laws or

- • that natural evils provide us with a knowledge of evil which makes our free choices more significant than they would otherwise be, and so our free will more valuable or

- • that natural evils are a mechanism of divine punishment for moral evils that humans have committed, and so the natural evil is justified.

Most scholars agree that Plantinga's free will of human and non-human

spirits (demons) argument successfully solves the logical problem of

evil, proving that God and evil are logically compatible but other scholars explicitly dissent.

The dissenters state that while explaining infectious diseases, cancer,

hurricanes and other nature-caused suffering as something that is

caused by the free will of supernatural beings solves the logical

version of the problem of evil, it is highly unlikely that these natural

evils do not have natural causes that an omnipotent God could prevent,

but instead are caused by the immoral actions of supernatural beings

with free will whom God created.

According to Michael Tooley, this defense is also highly implausible

because suffering from natural evil is localized, rational causes and

cures for major diseases have been found, and it is unclear why anyone,

including a supernatural being whom God created would choose to inflict

localized evil and suffering to innocent children for example, and why

God fails to stop such suffering if he is omnipotent.

- Free will and animal suffering

One of the weaknesses of the free will defense is its inapplicability

or contradictory applicability with respect to evils faced by animals

and the consequent animal suffering. Some scholars, such as David Griffin, state that the free will, or the assumption of greater good through free will, does not apply to animals.

In contrast, a few scholars while accepting that "free will" applies in

a human context, have posited an alternative "free creatures" defense,

stating that animals too benefit from their physical freedom though that

comes with the cost of dangers they continuously face.

The "free creatures" defense has also been criticized, in the

case of caged, domesticated and farmed animals who are not free and many

of whom have historically experienced evil and suffering from abuse by

their owners. Further, even animals and living creatures in the wild

face horrendous evils and suffering—such as burn and slow death after

natural fires or other natural disasters or from predatory injuries—and

it is unclear, state Bishop and Perszyk, why an all-loving God would

create such free creatures prone to intense suffering.

- Heaven and free will

There is also debate regarding the compatibility of moral free will

(to select good or evil action) with the absence of evil from heaven, with God's omniscience and with his omnibenevolence.

One line of extended criticism of free will defense has been that

if God is perfectly powerful, knowing and loving, then he could have

actualized a world with free creatures without moral evil where everyone

chooses good, is always full of loving-kindness, is compassionate,

always non-violent and full of joy, where earth were just like the

monotheistic concept of heaven.

If God did create a heaven with his love, an all-loving and

always-loving God could have created an earth without evil and suffering

for animals and human beings just like heaven.

Process theodicy

"Process theodicy reframes the debate on the problem of evil by denying one of its key premises: divine omnipotence."

It integrates philosophical and theological commitments while shifting

theological metaphors. For example, God becomes the Great Companion

and Fellow-Sufferer where the future is realized hand-in-hand with the

sufferer.

Soul-making or Irenaean theodicy

The soul-making or Irenaean theodicy is named after the 2nd-century Greek theologian Irenaeus, whose ideas were adopted in Eastern Christianity. It has been discussed by John Hick, and the Irenaean theodicy asserts that evil and suffering are necessary for spiritual growth, for man to discover his soul, and God allows evil for spiritual growth of human beings.

The Irenaean theodicy has been challenged with the assertion that

many evils do not seem to promote spiritual growth, and can be

positively destructive of the human spirit. Hick acknowledges that this

process often fails in our world.

A second issue concerns the distribution of evils suffered: were it

true that God permitted evil in order to facilitate spiritual growth,

then we would expect evil to disproportionately befall those in poor

spiritual health. This does not seem to be the case, as the decadent

enjoy lives of luxury which insulate them from evil, whereas many of the

pious are poor, and are well acquainted with worldly evils.

Thirdly, states Kane, human character can be developed directly or in

constructive and nurturing loving ways, and it is unclear why God would

consider or allow evil and suffering to be necessary or the preferred

way to spiritual growth.

Further, horrendous suffering often leads to dehumanization, its

victims in truth do not grow spiritually but become vindictive and

spiritually worse.

This reconciliation of the problem of evil and God, states

Creegan, also fails to explain the need or rationale for evil inflicted

on animals and resultant animal suffering, because "there is no evidence

at all that suffering improves the character of animals, or is evidence

of soul-making in them".

On a more fundamental level, the soul-making theodicy assumes

that the virtues developed through suffering are intrinsically, as

opposed to instrumentally, good. The virtues identified as "soul-making"

only appear to be valuable in a world where evil and suffering already

exist. A willingness to sacrifice oneself in order to save others from

persecution, for example, is virtuous precisely because persecution

exists. Likewise, we value the willingness to donate one's meal to those

who are starving because starvation exists. If persecution and

starvation did not occur, there would be no reason to consider these

acts virtuous. If the virtues developed through soul-making are only

valuable where suffering exists, then it is not clear that we would lose

anything if suffering did not exist.

Cruciform theodicy

Soul-making

theodicy and Process theodicy are full theodical systems with

distinctive cosmologies, theologies and perspectives on the problem of

evil; cruciform theodicy is not a system but is a thematic trajectory

within them. As a result, it does not address all the questions of "the

origin, nature, problem, reason and end of evil," but it does represent an important change. "On July 16, 1944 awaiting execution in a Nazi prison and reflecting on Christ's experience of powerlessness and pain, Dietrich Bonhoeffer penned six words that became the clarion call for the modern theological paradigm shift: 'Only the suffering God can help."

Classic theism includes "impassability" (God cannot suffer personally)

as a necessary characteristic of God. Cruciform theodicy begins with

Jesus' suffering "the entire spectrum of human sorrow, including

economic exploitation, political disenfranchisement, social ostracism,

rejection and betrayal by friends, even alienation from his own

family...deep psychological distress... [grief]..." ridicule,

humiliation, abandonment, beating, torture, despair, and death.

Theologian Jürgen Moltmann asserts the "passibility" of God saying "A God who cannot suffer cannot love." Philosopher and Christian priest Marilyn McCord Adams

offers a theodicy of "redemptive suffering" which proposes that

innocent suffering shows the "transformative power of redemption" rather

than that God is not omnibenevolent.

Afterlife

Thomas Aquinas suggested the afterlife theodicy to address the problem of evil and to justifying the existence of evil.

The premise behind this theodicy is that the afterlife is unending,

human life is short, and God allows evil and suffering in order to judge

and grant everlasting heaven or hell based on human moral actions and

human suffering. Aquinas says that the afterlife is the greater good that justifies the evil and suffering in current life. Christian author Randy Alcorn argues that the joys of heaven will compensate for the sufferings on earth.

Stephen Maitzen has called this the "Heaven Swamps Everything"

theodicy, and argues that it is false because it conflates compensation

and justification.

A second objection to the afterlife theodicy is that it does not

reconcile the suffering of small babies and innocent children from

diseases, abuse, and injury in war or terror attacks, since "human moral

actions" are not to be expected from babies and uneducated/mentored

children.

Similarly, moral actions and the concept of choice do not apply to the

problem of evil applied to animal suffering caused by natural evil or

the actions of human beings.

Deny evil exists

In

the second century, Christian theologists attempted to reconcile the

problem of evil with an omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent God, by

denying that evil exists. Among these theologians, Clement of Alexandria offered several theodicies, of which one was called "privation theory of evil" which was adopted thereafter.

The other is a more modern version of "deny evil", suggested by

Christian Science, wherein the perception of evil is described as a form

of illusion.

Evil as the absence of good (privation theory)

The early version of "deny evil" is called the "privation theory of

evil", so named because it described evil as a form of "lack, loss or

privation". One of the earliest proponents of this theory was the

2nd-century Clement of Alexandria, who according to Joseph Kelly,

stated that "since God is completely good, he could not have created

evil; but if God did not create evil, then it cannot exist". Evil,

according to Clement, does not exist as a positive, but exists as a

negative or as a "lack of good".

Clement's idea was criticised for its inability to explain suffering in

the world, if evil did not exist. He was also pressed by Gnostics

scholars with the question as to why God did not create creatures that

"did not lack the good". Clement attempted to answer these questions

ontologically through dualism, an idea found in the Platonic school, that is by presenting two realities, one of God and Truth, another of human and perceived experience.

The fifth-century theologian Augustine of Hippo adopted the privation theory, and in his Enchiridion on Faith, Hope and Love, maintained that evil exists only as "absence of the good", that vices are nothing but the privations of natural good. Evil is not a substance, states Augustine, it is nothing more than "loss of good". God does not participate in evil, God is perfection, His creation is perfection, stated Augustine. According to the privation theory, it is the absence of the good, that explains sin and moral evil.

This view has been criticized as merely substituting definition,

of evil with "loss of good", of "problem of evil and suffering" with the

"problem of loss of good and suffering", but it neither addresses the

issue from the theoretical point of view nor from the experiential point

of view.

Scholars who criticize the privation theory state that murder, rape,

terror, pain and suffering are real life events for the victim, and

cannot be denied as mere "lack of good".

Augustine, states Pereira, accepted suffering exists and was aware that

the privation theory was not a solution to the problem of evil.

Evil as illusory

An alternative modern version of the privation theory is by Christian Science,

which asserts that evils such as suffering and disease only appear to

be real, but in truth are illusions, and in reality evil does not exist.

The theologists of Christian Science, states Stephen Gottschalk, posit

that the Spirit is of infinite might, mortal human beings fail to grasp

this and focus instead on evil and suffering that have no real existence

as "a power, person or principle opposed to God".

The illusion version of privation theory theodicy has been

critiqued for denying the reality of crimes, wars, terror, sickness,

injury, death, suffering and pain to the victim.

Further, adds Millard Erickson, the illusion argument merely shifts the

problem to a new problem, as to why God would create this "illusion" of

crimes, wars, terror, sickness, injury, death, suffering and pain; and

why God does not stop this "illusion".

Turning the tables

A

different approach to the problem of evil is to turn the tables by

suggesting that any argument from evil is self-refuting, in that its

conclusion would necessitate the falsity of one of its premises. One

response—called the defensive response—has

been to assert the opposite, and to point out that the assertion "evil

exists" implies an ethical standard against which moral value is

determined, and then to argue that this standard implies the existence

of God.

The standard criticism of this view is that an argument from evil

is not necessarily a presentation of the views of its proponent, but is

instead intended to show how premises which the theist is inclined to

believe lead him or her to the conclusion that God does not exist. A

second criticism is that the existence of evil can be inferred from the

suffering of its victims, rather than by the actions of the evil actor,

so no "ethical standard" is implied. This argument was expounded upon by David Hume.

Hidden reasons

A

variant of above defenses is that the problem of evil is derived from

probability judgments since they rest on the claim that, even after

careful reflection, one can see no good reason for co-existence of God

and of evil. The inference from this claim to the general statement that there exists unnecessary evil is inductive in nature and it is this inductive step that sets the evidential argument apart from the logical argument.

The hidden reasons defense asserts that there exists the logical

possibility of hidden or unknown reasons for the existence of evil along

with the existence of an almighty, all-knowing, all-benevolent,

all-powerful God. Not knowing the reason does not necessarily mean that

the reason does not exist. This argument has been challenged with the assertion that the hidden

reasons premise is as plausible as the premise that God does not exist

or is not "an almighty, all-knowing, all-benevolent, all-powerful".

Similarly, for every hidden argument that completely or partially

justifies observed evils it is equally likely that there is a hidden

argument that actually makes the observed evils worse than they appear

without hidden arguments, or that the hidden reasons may result in

additional contradictions. As such, from an inductive viewpoint hidden arguments will neutralize one another.

A sub-variant of the "hidden reasons" defense is called the "PHOG"—profoundly hidden outweighing goods—defense.

The PHOG defense, states Bryan Frances, not only leaves the

co-existence of God and human suffering unanswered, but raises questions

about why animals and other life forms have to suffer from natural

evil, or from abuse (animal slaughter, animal cruelty) by some human

beings, where hidden moral lessons, hidden social good and such hidden

reasons to reconcile God with the problem of evil do not apply.

Previous lives and karma

The theory of karma

refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect where intent and

actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that individual

(effect).

The problem of evil, in the context of karma, has been long discussed

in Indian religions including Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism, both in

its theistic and non-theistic schools; for example, in Uttara Mīmāṃsā

Sutras Book 2 Chapter 1; the 8th-century arguments by Adi Sankara in Brahmasutrabhasya

where he posits that God cannot reasonably be the cause of the world

because there exists moral evil, inequality, cruelty and suffering in

the world; and the 11th-century theodicy discussion by Ramanuja in Sribhasya.

Many Indian religions place greater emphasis on developing the

karma principle for first cause and innate justice with Man as focus,

rather than developing religious principles with the nature and powers

of God and divine judgment as focus.

Karma theory of Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism is not static, but

dynamic wherein livings beings with intent or without intent, but with

words and actions continuously create new karma, and it is this that

they believe to be in part the source of good or evil in the world.

These religions also believe that past lives or past actions in current

life create current circumstances, which also contributes to either.

Other scholars suggest that nontheistic Indian religious traditions do not assume an omnibenevolent creator, and some

theistic schools do not define or characterize their god(s) as

monotheistic Western religions do and the deities have colorful, complex

personalities; the Indian deities are personal and cosmic facilitators,

and in some schools conceptualized like Plato’s Demiurge.

Therefore, the problem of theodicy in many schools of major Indian

religions is not significant, or at least is of a different nature than

in Western religions.

According to Arthur Herman, karma-transmigration theory solves

all three historical formulations to the problem of evil while

acknowledging the theodicy insights of Sankara and Ramanuja.

Pandeism

Pandeism

is a modern theory that unites deism and pantheism, and asserts that

God created the universe but during creation became the universe.

In pandeism, God is no superintending, heavenly power, capable of

hourly intervention into earthly affairs. No longer existing "above,"

God cannot intervene from above and cannot be blamed for failing

to do so. God, in pandeism, was omnipotent and omnibenevolent, but in

the form of universe is no longer omnipotent, omnibenevolent.

Monotheistic religions

Christianity

The Bible

Sociologist Walter Brueggemann

says theodicy is "a constant concern of the entire Bible" and needs to

"include the category of social evil as well as moral, natural

(physical) and religious evil".

There is general agreement among Bible scholars that the Bible "does

not admit of a singular perspective on evil. ...Instead we encounter a

variety of perspectives... Consequently [the Bible focuses on] moral

and spiritual remedies, not rational or logical [justifications]. ...It

is simply that the Bible operates within a cosmic, moral and spiritual

landscape rather than within a rationalist, abstract, ontological

landscape."

In the Holman Bible dictionary, evil is all that is "opposed to God

and His purposes or that which, from the human perspective, is harmful

and nonproductive."

Theologian Joseph Onyango narrows that definition saying that "If we

take the essentialist view of [biblical] ethics... evil is anything

contrary to God's good nature...(meaning His character or attributes)."

Philosopher Richard Swinburne

says that, as it stands in its classic form, the argument from evil is

unanswerable, yet there may be contrary reasons for not reaching its

conclusion that there is no God.

These reasons are of three kinds: other strong reasons for affirming

that there is a God; general reasons for doubting the force of the

argument itself; and specific reasons for doubting the criteria of any

of the argument's premises; "in other words, a theodicy."

Christianity has responded with multiple traditional theodicies: the

Punishment theodicy (Augustine), the Soul-making theodicy (Irenaeus),

Process theodicy (Rabbi Harold Kushner), Cruciform theodicy (Moltmann),

and the free-will defense (Plantinga) among them.

There are, essentially, four representations of evil in the Bible: chaos, human sin, Satanic/demonic forces, and suffering.

The biblical language of chaos and chaos monsters such as Leviathan

remind us order and harmony in our world are constantly assailed by

forces "inimical to God's good creation."

The Bible primarily speaks of sin as moral evil rather than natural or

metaphysical evil with an accent on the breaking of God's moral laws,

his covenant, the teachings of Christ and the injunctions of the Holy

Spirit.

The writers of the Bible take the reality of a spiritual world beyond

this world and its containment of hostile spiritual forces for granted.

While the post-Enlightenment world does not, the "dark spiritual forces"

can be seen as "symbols of the darkest recesses of human nature."

Suffering and misfortune are sometimes represented as evil in the

Bible, though theologian Brian Han Gregg says, suffering in the Bible is

represented twelve different ways.

- Deuteronomy 30 and Hebrews 12 open the possibilities that suffering may be punishment, natural consequences, or God's loving discipline.

- Genesis 4:1-8 and the first murder suggests much suffering is the result of certain people's choices.

- Genesis 45 says God's redemptive power is stronger than suffering and can be used to further good purposes.

- Luke 22:31-34 says resist the fear and despair that accompany suffering, instead remember/believe God has the power to help.

- Job 40 says God is not like humans but wants a relationship with all of them, which requires some surrender to God and acceptance of suffering.

- Romans 8:18-30 sets present temporary suffering within the context of God's eternal purposes.

- Hebrews 12:1-6 sets suffering within the concept of "soul-making" as do 2 Peter 1:5-8, James 1, and others.

- Exodus 17:1-7 and the whole book of Job characterize suffering as testing and speak of God's right to test human loyalty.

- 2 Corinthians 4:7-12 says human weakness during suffering reveals God's strength and that it is part of the believer's calling to embrace suffering in solidarity with Christ.

- 2 Corinthians 1:3-7 says God is the comforter and that people learn how to better comfort others when they have personal experience of suffering.

- The great hymn in Philippians 2, along with Colossians 1:24, combine to claim Christ redeems suffering itself. Believers are invited to share in that by emulating his good thoughts, words and deeds. All New Testament teachings on suffering are all grounded in and circle back to the fall of mankind and the possible redemptive power to individuals of the cross.

Jewish theodicy is experiencing extensive revision in light of the

Holocaust while still asserting the difference between the human and

divine perspective of evil. It remains rooted in the nature of creation

itself and the limitation inherent in matter's capacity to be perfected;

the action of freewill includes the potential for perfection from

individual effort and leaves evil in human hands.

In the Hebrew Bible Genesis says God's creation is "good" with evil depicted as entering creation as a result of human choice.

The book of Job "seeks to expand the understanding of divine justice

...beyond mere retribution, to include a system of divine sovereignty

[showing] the King has the right to test His subject's loyalty... [Job]

corrects the rigid and overly simplistic doctrine of retribution in

attributing suffering to sin and punishment." Hebrew Bible scholar Marvin A. Sweeney

says "...a unified reading of [Isaiah] places the question of theodicy

at the forefront... [with] three major dimensions of the question:

Yahweh's identification with the conqueror, Yahweh's decree of judgment

against Israel without possibility of repentance, and the failure of

Yahweh's program to be realized by the end of the book."

Ezekiel and Jeremiah confront the concept of personal moral

responsibility and understanding divine justice in a world under divine

governance. "Theodicy in the Minor Prophets differs little from that in Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel."

In the Psalms more personal aspects of theodicy are discussed, such as

Psalm 73 which confronts the internal struggle created by suffering.

Theodicy in the Hebrew Bible almost universally looks "beyond the

concerns of the historical present to posit an eschatological salvation"

at that future time when God restores all things.

In the Bible, all characterizations of evil and suffering reveal

"a God who is greater than suffering [who] is powerful, creative and

committed to His creation [who] always has the last word." God's

commitment to the greater good is assumed in all cases.

Judgment Day

John Joseph Haldane's Wittgenstinian-Thomistic account of concept formation and Martin Heidegger's observation of temporality's thrown nature

imply that God's act of creation and God's act of judgment are the same

act. God's condemnation of evil is subsequently believed to be executed

and expressed in his created world; a judgement that is unstoppable due

to God's all powerful will; a constant and eternal judgement that

becomes announced and communicated to other people on Judgment Day. In this explanation, God's condemnation of evil is declared to be a good judgement.

Irenaean theodicy

Irenaean theodicy, posited by Irenaeus (2nd century CE–c. 202), has been reformulated by John Hick. It holds that one cannot achieve moral goodness or love for God if there is no evil and suffering in the world. Evil is soul-making and leads one to be truly moral and close to God. God created an epistemic

distance (such that God is not immediately knowable) so that we may

strive to know him and by doing so become truly good. Evil is a means to

good for three main reasons:

- Means of knowledge – Hunger leads to pain, and causes a desire to feed. Knowledge of pain prompts humans to seek to help others in pain.

- Character building – Evil offers the opportunity to grow morally. "We would never learn the art of goodness in a world designed as a hedonistic paradise" (Richard Swinburne)

- Predictable environment – The world runs to a series of natural laws. These are independent of any inhabitants of the universe. Natural Evil only occurs when these natural laws conflict with our own perceived needs. This is not immoral in any way

Augustinian theodicy

St Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) in his Augustinian theodicy, as presented in John Hick's book Evil and the God of Love,

focuses on the Genesis story that essentially dictates that God created

the world and that it was good; evil is merely a consequence of the fall of man (The story of the Garden of Eden where Adam and Eve disobeyed God and caused inherent sin for man). Augustine stated that natural evil (evil present in the natural world such as natural disasters etc.) is caused by fallen angels, whereas moral evil

(evil caused by the will of human beings) is as a result of man having

become estranged from God and choosing to deviate from his chosen path.

Augustine argued that God could not have created evil in the world, as

it was created good, and that all notions of evil are simply a deviation

or privation of goodness. Evil cannot be a separate and unique

substance. For example, Blindness is not a separate entity, but is

merely a lack or privation of sight. Thus the Augustinian theodicist

would argue that the problem of evil and suffering is void because God

did not create evil; it was man who chose to deviate from the path of

perfect goodness.

St. Thomas Aquinas

Saint

Thomas systematized the Augustinian conception of evil, supplementing

it with his own musings. Evil, according to St. Thomas, is a privation,

or the absence of some good which belongs properly to the nature of the

creature. There is therefore no positive source of evil, corresponding to the greater good, which is God;

evil being not real but rational—i.e. it exists not as an objective

fact, but as a subjective conception; things are evil not in themselves,

but by reason of their relation to other things or persons. All

realities are in themselves good; they produce bad results only

incidentally; and consequently the ultimate cause of evil is

fundamentally good, as well as the objects in which evil is found.

Luther and Calvin

Both Luther and Calvin explained evil as a consequence of the fall of man and the original sin. Calvin, however, held to the belief in predestination

and omnipotence, the fall is part of God's plan. Luther saw evil and

original sin as an inheritance from Adam and Eve, passed on to all

mankind from their conception and bound the will of man to serving sin,

which God's just nature allowed as consequence for their distrust,

though God planned mankind's redemption through Jesus Christ. Ultimately humans may not be able to understand and explain this plan.

Liberal Christianity

Some modern liberal Christians, including French Calvinist theologian André Gounelle and Pastor Marc Pernot of L'Oratoire du Louvre, believe that God is not omnipotent, and that the Bible only describes God as "almighty" in passages concerning the End Times.

Christian Science

Christian Science

views evil as having no ultimate reality and as being due to false

beliefs, consciously or unconsciously held. Evils such as illness and

death may be banished by correct understanding. This view has been

questioned, aside from the general criticisms of the concept of evil as

an illusion discussed earlier, since the presumably correct

understanding by Christian Science members, including the founder, has

not prevented illness and death.

However, Christian Scientists believe that the many instances of

spiritual healing (as recounted e.g. in the Christian Science

periodicals and in the textbook Science and Health with Key to the

Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy) are anecdotal evidence of the correctness of the teaching of the unreality of evil.

According to one author, the denial by Christian Scientists that evil

ultimately exists neatly solves the problem of evil; however, most

people cannot accept that solution

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that Satan is the original cause of evil.

Though once a perfect angel, Satan developed feelings of

self-importance and craved worship, and eventually challenged God's

right to rule. Satan caused Adam and Eve

to disobey God, and humanity subsequently became participants in a

challenge involving the competing claims of Jehovah and Satan to

universal sovereignty. Other angels who sided with Satan became demons.

God's subsequent tolerance of evil is explained in part by the

value of free will. But Jehovah's Witnesses also hold that this period

of suffering is one of non-interference from God, which serves to

demonstrate that Jehovah's

"right to rule" is both correct and in the best interests of all

intelligent beings, settling the "issue of universal sovereignty".

Further, it gives individual humans the opportunity to show their

willingness to submit to God's rulership.

At some future time known to him, God will consider his right to universal sovereignty to have been settled for all time. The reconciliation of "faithful" humankind will have been accomplished through Christ,

and nonconforming humans and demons will have been destroyed.

Thereafter, evil (any failure to submit to God's rulership) will be

summarily executed.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) introduces a concept similar to Irenaean theodicy,

that experiencing evil is a necessary part of the development of the

soul. Specifically, the laws of nature prevent an individual from fully

comprehending or experiencing good without experiencing its opposite. In this respect, Latter-day Saints do not regard the fall of Adam and Eve

as a tragic, unplanned cancellation of an eternal paradise; rather they

see it as an essential element of God's plan. By allowing opposition

and temptations in mortality, God created an environment for people to

learn, to develop their freedom to choose, and to appreciate and

understand the light, with a comparison to darkness.

This is a departure from the mainstream Christian definition of omnipotence and omniscience, which Mormons believe was changed by post-apostolic theologians in the centuries after Christ. The writings of Justin Martyr, Origen, Augustine, and others indicate a merging of Christian principles with Greek metaphysical philosophies such as Neoplatonism, which described divinity as an utterly simple, immaterial, formless substance/essence (ousia) that was the absolute causality and creative source of all that existed. Mormons teach that through modern day revelation,

God restored the truth about his nature, which eliminated the

speculative metaphysical elements that had been incorporated after the Apostolic era.

As such, God's omniscience/omnipotence is not to be understood as

metaphysically transcending all limits of nature, but as a perfect

comprehension of all things within nature—which gives God the power to bring about any state or condition within those bounds. This restoration also clarified that God does not create Ex nihilo (out of nothing), but uses existing materials to organize order out of chaos.

Because opposition is inherent in nature, and God operates within

nature’s bounds, God is therefore not considered the author of evil, nor

will He eradicate all evil from the mortal experience.

His primary purpose, however, is to help His children to learn for

themselves to both appreciate and choose the right, and thus achieve

eternal joy and live in his presence, and where evil has no place.

Islam

Islamic scholars in the medieval and modern era have tried to reconcile the problem of evil with the afterlife theodicy.

According to Nursi, the temporal world has many evils such as the

destruction of Ottoman Empire and its substitution with secularism, and

such evils are impossible to understand unless there is an afterlife.

The omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent god in Islamic thought

creates everything, including human suffering and its causes (evil). Evil was neither bad nor needed moral justification from God, but rewards awaited believers in the afterlife. The faithful suffered in this short life, so as to be judged by God and enjoy heaven in the never-ending afterlife.

Alternate theodicies in Islamic thought include the 11th-century

Ibn Sina's denial of evil in a form similar to "privation theory"

theodicy.

This theodicy attempt by Ibn Sina is unsuccessful, according to Shams

Inati, because it implicitly denies the omnipotence of God.

Judaism

According to Jon Levenson, the writers of Hebrew Bible were well

aware of evil as a theological problem, but he does not claim awareness

of the problem of evil.

In contrast, according to Yair Hoffman, the ancient books of the Hebrew

Bible do not show an awareness of the theological problem of evil, and

even most later biblical scholars did not touch the question of the

problem of evil.

The earliest awareness of the problem of evil in Judaism tradition is

evidenced in extra- and post-biblical sources such as early Apocrypha (secret texts by unknown authors, which were not considered mainstream at the time they were written). The first systematic reflections on the problem of evil by Jewish philosophers is traceable only in the medieval period.

The problem of evil gained renewed interest among Jewish scholars after the moral evil of the Holocaust.

The all-powerful, all-compassionate, all-knowing monotheistic God

presumably had the power to prevent the Holocaust, but he didn't.

The Jewish thinkers have argued that either God did not care about the

torture and suffering in the world He created—which means He is not

omnibenevolent, or He did not know what was happening—which means He is

not omniscient.

The persecution of Jewish people was not a new phenomenon, and medieval

Jewish thinkers had in abstract attempted to reconcile the logical

version of the problem of evil. The Holocaust experience and other episodes of mass extermination such as the Gulag and the Killing Fields

where millions of people experienced torture and died, however, brought

into focus the visceral nature of the evidential version of the problem

of evil.

The 10th-century Rabbi called Saadia Gaon presented a theodicy along the lines of "soul-making, greater good and afterlife". Suffering suggested Saadia, in a manner similar to Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 5, should be considered as a gift from God because it leads to an eternity of heaven in afterlife. In contrast, the 12th-century Moses Maimonides

offered a different theodicy, asserting that the all-loving God neither

produces evil nor gifts suffering, because everything God does is

absolutely good, then presenting the "privation theory" explanation. Both these answers, states Daniel Rynhold, merely rationalize and suppress the problem of evil, rather than solve it.

It is easier to rationalize suffering caused by a theft or accidental

injuries, but the physical, mental and existential horrors of persistent

events of repeated violence over long periods of time such as

Holocaust, or an innocent child slowly suffering from the pain of

cancer, cannot be rationalized by one sided self blame and belittling a

personhood.

Attempts by theologians to reconcile the problem of evil, with claims

that the Holocaust evil was a necessary, intentional and purposeful act

of God have been declared obscene by Jewish thinkers such as Richard

Rubenstein.

Other religions

Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt

The ancient Egyptian

religion, according to Roland Enmarch, potentially absolved their gods

from any blame for evil, and used a negative cosmology and the negative

concept of human nature to explain evil.

Further, the Pharaoh was seen as an agent of the gods and his actions

as a king were aimed to prevent evil and curb evilness in human nature.

Ancient Greek religion

The gods in Ancient Greek religion were seen as superior, but shared similar traits with humans and often interacted with them.

Although the Greeks didn't believe in any "evil" gods, the Greeks still

acknowledged the fact that evil was present in the world.

Gods often meddled in the affairs of men, and sometimes their actions

consisted of bringing misery to people, for example gods would sometimes

be a direct cause of death for people.

However, the Greeks did not consider the gods to be evil as a result of

their actions, instead the answer for most situations in Greek

mythology was the power of fate. Fate is considered to be more powerful than the gods themselves and for this reason no one can escape it. For this reason the Greeks recognized that unfortunate events were justifiable by the idea of fate.

Later Greek and Roman theologians and philosophers discussed the

problem of evil in depth. Starting at least with Plato, philosophers

tended to reject or de-emphasize literal interpretations of mythology in

favor of a more pantheistic, natural theology

based on reasoned arguments. In this framework, stories that seemed to

impute dishonorable conduct to the gods were often simply dismissed as

false, and as being nothing more than the "imagination of poets." Greek

and Roman thinkers continued to wrestle, however, with the problems of natural evil and of evil that we observe in our day-to-day experience. Influential Roman writers such as Cicero and Seneca, drawing on earlier work by the Greek philosophers such as the Stoics,

developed many arguments in defense of the righteousness of the gods,

and many of the answers they provided were later absorbed into Christian

theodicy.

Buddhism

Buddhism

neither denies the existence of evil, nor does it attempt to reconcile

evil in a way attempted by monotheistic religions that assert the

existence of an almighty, all powerful, all knowing, all benevolent God. Buddhism, as a non-theistic religion like Jainism, does not assume or assert any creator God, and thus the problem of evil or of theodicy does not apply to it. It considers a benevolent, omnipotent creator god as attachment to be a false concept.

Buddhism accepts that there is evil in the world, as well as Dukkha

(suffering) that is caused by evil or because of natural causes (aging,

disease, rebirth). The precepts and practices of Buddhism, such as Four Noble Truths and Noble Eightfold Path aim to empower a follower in gaining insights and liberation (nirvana) from the cycle of such suffering as well as rebirth.

Some strands of Mahayana Buddhism developed a theory of Buddha-nature in texts such as the Tathagata-garbha Sutras composed in 3rd-century south India, which is very similar to the "soul, self" theory found in classical Hinduism. The Tathagata-garbha theory leads to a Buddhist version of the problem of evil, states Peter Harvey,

because the theory claims that every human being has an intrinsically

pure inner Buddha which is good. This premise leads to the question as

to why anyone does any evil, and why doesn't the "intrinsically pure

inner Buddha" attempt or prevail in preventing the evil actor before he

or she commits the evil. One response has been that the Buddha-nature is omnibenevolent, but not omnipotent. Further, the Tathagata-garbha Sutras are atypical texts of Buddhism, because they contradict the Anatta doctrines in a vast majority of Buddhist texts, leading scholars to posit that the Tathagatagarbha Sutras were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists, and that they do not represent mainstream Buddhism.

The mainstream Buddhism, from its early days, did not need to

address the theological problem of evil as it saw no need for a creator

of the universe and asserted instead, like many Indian traditions, that

the universe never had a beginning and all existence is an endless cycle

of rebirths (samsara).

Hinduism

Hinduism is a complex religion with many different currents or schools.

Its non-theist traditions such as Samkhya, early Nyaya, Mimamsa and

many within Vedanta do not posit the existence of an almighty,

omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent God (monotheistic God), and the

classical formulations of the problem of evil and theodicy do not apply

to most Hindu traditions. Further, deities in Hinduism are neither eternal nor omnipotent nor omniscient nor omnibenevolent. Devas are mortal and subject to samsara. Evil as well as good, along with suffering is considered real and caused by human free will, its source and consequences explained through the karma doctrine of Hinduism, as in other Indian religions.

A version of the problem of evil appears in the ancient Brahma Sutras, probably composed between 200 BCE and 200 CE, a foundational text of the Vedanta tradition of Hinduism.

Its verses 2.1.34 through 2.1.36 aphoristically mention a version of

the problem of suffering and evil in the context of the abstract

metaphysical Hindu concept of Brahman. The verse 2.1.34 of Brahma Sutras asserts that inequality and cruelty in the world cannot be attributed to the concept of Brahman, and this is in the Vedas and the Upanishads. In his interpretation and commentary on the Brahma Sutras,

the 8th-century scholar Adi Shankara states that just because some

people are happier than others and just because there is so much malice,

cruelty and pain in the world, some state that Brahman cannot be the

cause of the world.

For that would lead to the possibility of partiality and cruelty. For it can be reasonably concluded that God has passion and hatred like some ignoble persons... Hence there will be a nullification of God's nature of extreme purity, (unchangeability), etc., [...] And owing to infliction of misery and destruction on all creatures, God will be open to the charge of pitilessness and extreme cruelty, abhorred even by a villain. Thus on account of the possibility of partiality and cruelty, God is not an agent.

— Purvapaksha by Adi Shankara, Translated by Arvind Sharma

Shankara attributes evil and cruelty in the world to Karma of oneself, of others, and to ignorance, delusion and wrong knowledge, but not to the abstract Brahman. Brahman itself is beyond good and evil. There is evil and suffering because of karma.

Those who struggle with this explanation, states Shankara, do so

because of presumed duality, between Brahman and Jiva, or because of

linear view of existence, when in reality "samsara and karma are anadi"

(existence is cyclic, rebirth and deeds are eternal with no beginning). In other words, in the Brahma Sutras, the formulation of problem of evil is considered a metaphysical construct, but not a moral issue. Ramanuja of the theistic Sri Vaishnavism

school—a major tradition within Vaishnavism—interprets the same verse

in the context of Vishnu, and asserts that Vishnu only creates

potentialities.

According to Swami Gambhirananda of Ramakrishna Mission,

Sankara's commentary explains that God cannot be charged with partiality

or cruelty (i.e. injustice) on account of his taking the factors of

virtuous and vicious actions (Karma) performed by an individual in

previous lives. If an individual experiences pleasure or pain in this

life, it is due to virtuous or vicious action (Karma) done by that

individual in a past life.

A sub-tradition within the Vaishnavism school of Hinduism that is an exception is dualistic Dvaita, founded by Madhvacharya

in the 13th-century. This tradition posits a concept of God so similar

to Christianity, that Christian missionaries in colonial India suggested

that Madhvacharya was likely influenced by early Christians who

migrated to India, a theory that has been discredited by scholars. Madhvacharya was challenged by Hindu scholars on the problem of evil, given his dualistic Tattvavada theory that proposed God and living beings along with universe as separate realities. Madhvacharya asserted, Yathecchasi tatha kuru,

which Sharma translates and explains as "one has the right to choose

between right and wrong, a choice each individual makes out of his own

responsibility and his own risk".

Madhva's reply does not address the problem of evil, state Dasti and

Bryant, as to how can evil exist with that of a God who is omnipotent,

omniscient, and omnibenevolent.

According to Sharma, "Madhva's tripartite classification of souls makes it unnecessary to answer the problem of evil".

According to David Buchta, this does not address the problem of evil,

because the omnipotent God "could change the system, but chooses not to"

and thus sustains the evil in the world. This view of self's agency of Madhvacharya was, states Buchta, an outlier in Vedanta school and Indian philosophies in general.

By philosopher

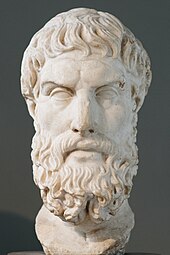

The earliest statement of the problem of evil is attributed to Epicurus, but this is uncertain.

Epicurus

Epicurus is generally credited with first expounding the problem of evil, and it is sometimes called the "Epicurean paradox", the "riddle of Epicurus", or the "Epicurus' trilemma":

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil?

Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

— The Epicurean paradox, ~300 BCE

There is no surviving written text of Epicurus that establishes that

he actually formulated the problem of evil in this way, and it is

uncertain that he was the author. An attribution to him can be found in a text dated about 600 years later, in the 3rd century Christian theologian Lactantius's Treatise on the Anger of God

where Lactantius critiques the argument. Epicurus's argument as

presented by Lactantius actually argues that a god that is all-powerful

and all-good does not exist and that the gods are distant and uninvolved

with man's concerns. The gods are neither our friends nor enemies.

David Hume

David Hume's formulation of the problem of evil in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion:

"Is he [God] willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?"

"[God's] power we allow [is] infinite: Whatever he wills is executed: But neither man nor any other animal are happy: Therefore he does not will their happiness. His wisdom is infinite: He is never mistaken in choosing the means to any end: But the course of nature tends not to human or animal felicity: Therefore it is not established for that purpose. Through the whole compass of human knowledge, there are no inferences more certain and infallible than these. In what respect, then, do his benevolence and mercy resemble the benevolence and mercy of men?"

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Leibniz

In his Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, the sceptic Pierre Bayle denied the goodness and omnipotence of God on account of the sufferings experienced in this earthly life. Gottfried Leibniz introduced the term theodicy in his 1710 work Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal

("Theodicic Essays on the Benevolence of God, the Free will of man, and

the Origin of Evil") which was directed mainly against Bayle. He argued

that this is the best of all possible worlds that God could have created.

Imitating the example of Leibniz, other philosophers also called their treatises on the problem of evil theodicies. Voltaire's popular novel Candide mocked Leibnizian optimism through the fictional tale of a naive youth.

Thomas Robert Malthus

The population and economic theorist Thomas Malthus

stated in a 1798 essay that people with health problems or disease are

not suffering, and should not viewed as such. Malthus argued, "Nothing

can appear more consonant to our reason than that those beings which

come out of the creative process of the world in lovely and beautiful

forms should be crowned with immortality, while those which come out

misshapen, those whose minds are not suited to a purer and happier state

of existence, should perish and be condemned to mix again with their

original clay. Eternal condemnation of this kind may be considered as a

species of eternal punishment, and it is not wonderful that it should be

represented, sometimes, under images of suffering."

Malthus believed in the Supreme Creator, considered suffering as

justified, and suggested that God should be considered "as pursuing the

creatures that had offended him with eternal hate and torture, instead

of merely condemning to their original insensibility those beings that,

by the operation of general laws, had not been formed with qualities

suited to a purer state of happiness."

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant wrote an essay on theodicy.

He suggested, states William Dembski, that any successful theodicy must

prove one of three things: [1] what one deems contrary to the

purposefulness of world is not so; [2] if one deems it is contrary, then

one must consider it not as a positive fact, but inevitable consequence

of the nature of things; [3] if one accepts that it is a positive fact,

then one must posit that it is not the work of God, but of some other

beings such as man or superior spirits, good or evil.

Kant did not attempt or exhaust all theodicies to help address

the problem of evil. He claimed there is a reason all possible

theodicies must fail.

While a successful philosophical theodicy has not been achieved in his

time, added Kant, there is no basis for a successful anti-theodicy

either.

Corollaries

Problem of good

Several philosophers

have argued that just as there exists a problem of evil for theists who

believe in an omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent being, so too

is there a problem of good for anyone who believes in an omniscient,

omnipotent, and omnimalevolent (or perfectly evil) being. As it appears

that the defenses and theodicies which might allow the theist to resist

the problem of evil can be inverted and used to defend belief in the

omnimalevolent being, this suggests that we should draw similar

conclusions about the success of these defensive strategies. In that

case, the theist appears to face a dilemma: either to accept that both

sets of responses are equally bad, and so that the theist does not have

an adequate response to the problem of evil; or to accept that both sets

of responses are equally good, and so to commit to the existence of an

omnipotent, omniscient, and omnimalevolent being as plausible.

Critics have noted that theodicies and defenses are often

addressed to the logical problem of evil. As such, they are intended

only to demonstrate that it is possible that evil can co-exist

with an omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. Since the

relevant parallel commitment is only that good can co-exist with an

omniscient, omnipotent and omnimalevolent being, not that it is

plausible that they should do so, the theist who is responding to the

problem of evil need not be committing himself to something he is likely

to think is false. This reply, however, leaves the evidential problem of evil untouched.

Morality

Another

general criticism is that though a theodicy may harmonize God with the

existence of evil, it does so at the cost of nullifying morality. This

is because most theodicies assume that whatever evil there is exists

because it is required for the sake of some greater good. But if an evil

is necessary because it secures a greater good, then it appears we

humans have no duty to prevent it, for in doing so we would also prevent

the greater good for which the evil is required. Even worse, it seems

that any action can be rationalized, as if one succeeds in performing

it, then God has permitted it, and so it must be for the greater good.

From this line of thought one may conclude that, as these conclusions

violate our basic moral intuitions, no greater good theodicy is true,

and God does not exist. Alternatively, one may point out that greater

good theodicies lead us to see every conceivable state of affairs as

compatible with the existence of God, and in that case the notion of

God's goodness is rendered meaningless.