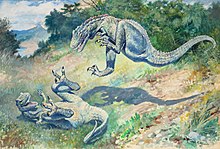

Leaping Laelaps by Charles R. Knight, 1896

Paleoart (also spelled palaeoart, paleo-art, or paleo art) is any original artistic work that attempts to depict prehistoric life according to the scientific evidence.

Works of paleoart may be representations of fossil remains or

depictions of the living creatures and their ecosystems. While paleoart

is typically defined as being scientifically informed, it is also

recognized as important in influencing depictions of prehistoric animals

in popular culture media, which in turn influences public perception

of, and fuels interest in, these animals.

The term "paleoart"–which is a portmanteau of paleo, the Ancient Greek word for "old," and "art"–was introduced in the late 1980s by Mark Hallett for art that depicts subjects related to paleontology, but is considered to have originated as a visual tradition in early 1800s England.

Older works of possible "proto-paleoart", suggestive of ancient fossil

discoveries, may date to as old as the 5th century BCE, though these

older works' relation to known fossil material is speculative. Other

artworks from the late Middle Ages

of Europe, typically portraying mythical creatures, are more plausibly

inspired by fossils of prehistoric large mammals and reptiles that were

known from this period.

Paleoart emerged as a distinct genre of art with unambiguous

scientific basis around the beginning of the 19th century, dovetailing

with the emergence of paleontology

as a distinct scientific discipline. These early paleoartists restored

fossil material, musculature, life appearance, and habitat of

prehistoric animals based on the limited scientific understanding of the

day. Paintings and sculptures from the mid 1800s were integral in

bringing paleontology to the interest of the general public, such as the

landmark Crystal Palace Dinosaur sculptures displayed in London.

Paleoart developed in scope and accuracy alongside paleontology, with

"classic" paleoart coming on the heels of rapid increase in dinosaur

discoveries resulting from the opening of the American frontier in the nineteenth century. Paleoartist Charles R. Knight, the first to depict dinosaurs as active animals, dominated the paleoart landscape through the early 1900s.

The modern era of paleoart was brought first by the "Dinosaur

Renaissance", a minor scientific revolution beginning in the early 1970s

in which dinosaurs came to be understood as active, alert creatures

that may have been warm-blooded and likely related to birds.

This change of landscape led to a stronger emphasis on accuracy,

novelty, and a focus on depicting prehistoric creatures as real animals

that resemble living animals in their appearance, behavior and

diversity. The "modern" age of paleoart is characterized by this focus

on accuracy and diversity in style and depiction, as well as by the rise

of digital art and a greater access to scientific resources and to a sprawling scientific and artistic community made possible by the Internet.

Today, paleoart is a globally-recognized genre of scientific art, and

has been the subject of international contests and awards, galleries,

and a variety of books and other merchandise.

Definitions

A

chief driver in the inception of paleoart as a distinct form of

scientific illustration was the desire of both the public and of

paleontologists to visualize the prehistory that fossils represented.

Mark Hallett, who coined the term "paleoart" in 1987, stressed the

importance of the cooperative effort between artists, paleontologists

and other specialists in gaining access to information for generating

accurate, realistic restorations of extinct animals and their

environments.

Since paleontological knowledge and public perception of the

field have changed dramatically since the earliest attempts at

reconstructing prehistory, paleoart as a discipline has consequently

changed over time as well. This has led to difficulties in creating a

shared definition of the term. Given that the drive towards scientific

accuracy has always been a salient feature of the discipline, some

authors point out the importance of separating true paleoart from

"paleoimagery", which is defined as a broader category of

paleontology-influenced imagery that may include a variety of cultural

and media depictions of prehistoric life in various manifestations, but

does not necessarily include scientific accuracy as a recognized goal.

One attempt to separate these terms has defined paleoartists as artists

who, "create original skeletal reconstructions and/or restorations of

prehistoric animals, or restore fossil flora or invertebrates using

acceptable and recognized procedures."

Others have pointed out that a definition of paleoart must include a

degree of subjectivity, where an artist's style, preferences and

opinions come into play along with the goal of accuracy. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

has offered the definition of paleoart as, "the scientific or

naturalistic rendering of paleontological subject matter pertaining to vertebrate fossils", a definition considered unacceptable by some for its exclusion of non-vertebrate subject matter. Paleoartist Mark Witton

defines paleoart in terms of three essential elements: 1) being bound

by scientific data, 2) involving biologically-informed restoration to

fill in missing data, and 3) relating to extinct organisms.

This definition explicitly rules out technical illustrations of fossil

specimens from being considered paleoart, and requires the use of

"reasoned extrapolation and informed speculation" to fill in these

reconstructive gaps, thereby also explicitly ruling out artworks that

actively go against known published data. These might be more accurately

considered paleontologically-inspired art.

In an attempt to establish a common definition of the term, Ansón

and colleagues (2015) conducted an empirical survey of the

international paleontological community with a questionnaire on various

aspects of paleoart. 78% of the surveyed participants stated agreement

with the importance of scientific accuracy in paleoart, and 87% of

respondents recognized an increase in accuracy of paleoart over time.

Aims and production

The

production of paleoart requires by definition substantial reading of

research and reference-gathering to ensure scientific credibility at the

time of production. Aims of paleoart range from communicating scientific knowledge to evoking emotion through fascination at nature. The artist James Gurney, known for the Dinotopia

series of fiction books, has described the interaction between

scientists and artists as the artist being the eyes of the scientist,

since his illustrations bring shape to the theories; paleoart determines

how the public perceives long extinct animals.

Apart from the goal of accuracy on its own, the intentions of the

paleoartist may be manifold, and include the illustrating of specific

scientific hypotheses, suggesting new hypotheses, or anticipating

paleontological knowledge through illustration that can be later

verified by fossil evidence.

Paleoart can even be used as a research methodology in itself, such as

in the creation of scale models to estimate weight approximations and

size proportions.

Paleoart is also frequently used as a tool for public outreach and

education, including through the production and sale of

paleontology-themed toys, books, movies, and other products.

An example of the skeletal reconstructions on which many paleoartists depend: Olorotitan by Andrey Atuchin

Scientific principles

Although

every artist's process will differ, Witton (2018) recommends a standard

set of requirements to produce artwork that fits the definition. A

basic understanding of the subject organism's place in time (geochronology) and space (paleobiogeography) is necessary for restorations of scenes or environments in paleoart. Skeletal reference—not just the bones of vertebrate animals, but including any fossilized structures of soft tissue–such as lignified plant tissue and coral

framework—is crucial for understanding the proportions, size and

appearance of extinct organisms. Given that many fossil specimens are

known from fragmentary material, an understanding of the organisms' ontogeny, functional morphology, and phylogeny may be required to create scientifically-rigorous paleoart by filling in restorative gaps parsimoniously.

Several professional paleoartists recommend the consideration of

contemporary animals in aiding accurate restorations, especially in

cases where crucial details of pose, appearance and behavior are

impossible to know from fossil material.

For example, most extinct animals' coloration and patterning are

unknown from fossil evidence, but these can be plausibly restored in

illustration based on known aspects of the animal's environment and

behavior, as well as inference based on function such as thermoregulation, species recognition, and camouflage.

Artistic principles

In

addition to a scientific understanding, paleoart incorporates a

traditional approach to art, the use and development of style, medium,

and subject matter that is unique to each artist.

The success of a piece of paleoart depends on its strength of

composition as much as any other genre of artistry. Command of object

placement, color, lighting, and shape can be indispensable to

communicating a realistic depiction of prehistoric life.

Drawing skills also help form an important basis of effective

paleoillustration, including an understanding of perspective,

composition, command of a medium, and practice at life drawing.

Paleoart is unique in its compositional challenge in that its content

must be imagined and inferred, as opposed to directly referenced, and,

in many cases, this includes animal behavior and environment. To this end, artists must keep in mind the mood and purpose of a composition in creating an effect piece of paleoart.

Many artists and enthusiasts think of paleoart as having validity

as art for its own sake. The incomplete nature of the fossil record,

varying interpretations of what material exists, and the inability to

observe behavior ensures that the illustration of dinosaurs has a

speculative component. Therefore, a variety of factors other than

science can influence paleontological illustrators, including the

expectations of editors, curators, and commissioners, as well as

long-standing assumptions about the nature of dinosaurs that may be

repeated through generations of paleoart, regardless of accuracy.

History

"Proto-paleoart" (pre-1800)

While

the word "paleoart" is relatively recent, the practice of restoring

ancient life based on real fossil remains can be considered to have

originated around the same time as paleontology. However, art of extinct animals has existed long before Henry De la Beche's 1830 painting Duria Antiquior, which is sometimes credited as the first true paleontological artwork.

These older works include sketches, paintings and detailed anatomical

restorations, though the relation of these works to observed fossil

material is mostly speculative. For example, a Corinthian vase painted sometime between 560 and 540 BCE

is thought by some researchers to bear a depiction of an observed

fossil skull. This so-called "Monster of Troy," the beast fought by the mythological Greek hero Heracles, somewhat resembles the skull of the giraffid Samotherium.

Witton considered that because the painting has significant differences

from the skull it is supposedly representing (lack of horns, sharp

teeth), it should not necessarily be considered "proto-paleoart." Other

scholars have suggested that ancient fossils inspired Grecian depictions of griffins,

with the mythical chimera of lion and bird anatomy superficially

resembling the beak, horns and quadrupedal body plan of the dinosaur Protoceratops.

Similarly, authors have speculated that the huge, unified nasal opening

in the skull of fossil mammoths could have inspired ancient artwork and

stories of the one-eyed cyclops.

However, these ideas have never been adequately substantiated, with

existing evidence more parsimonious with established cultural

interpretations of these mythical figures.

The Klagenfurt Lindworm

The earliest definitive works of "proto-paleoart" that unambiguously

depict the life appearance of fossil animals come from fifteenth and

sixteenth century Europe. One such depiction is Ulrich Vogelsang's

statue of a Lindwurm in Klagenfurt, Austria that dates to 1590. Writings from the time of its creation specifically identify the skull of Coelodonta antiquitatis,

the woolly rhinoceros, as the basis for the head in the restoration.

This skull had been found in a mine or gravel pit near Klagenfurt in

1335, and remains on display today. Despite its poor resemblance of the

skull in question, the Lindwurm statue was thought to be almost

certainly inspired by the find.

The German textbook Mundus Subterraneus, authored by scholar Athanasius Kircher in 1678, features a number of illustrations of giant humans and dragons

that may have been informed by fossil finds of the day, many of which

came from quarries and caves. Some of these may have been the bones of

large Pleistocene mammals common to these European caves. Others may have been based on far older fossils of plesiosaurs,

which are thought to have informed a unique depiction of a dragon in

this book that departs noticeably from the classically slender,

serpentine dragon artwork of the era by having a barrel-like body and

'paddle-like' wings. According to some researchers, this dramatic

departure from the typical dragon artwork of this time, which is thought

to have been informed by the Lindwurm, likely reflects the arrival of a

new source of information, such as a speculated discovery of plesiosaur

fossils in quarries of the historic Swabia region of Bavaria.

Eighteenth century skeletal reconstructions of the unicorn are thought to have been inspired by Ice Age mammoth and rhinoceros bones found in a cave near Quedlinburg, Germany in 1663. These artworks are of uncertain origin and may have been created by Otto von Guericke, the German naturalist who first described the "unicorn" remains in his writings, or Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,

the author who published the image posthumously in 1749. This rendering

represents the oldest known illustration of a fossil skeleton.

Early scientific paleoart (1800–1890)

Jean Hermann's 1800 restoration of the pterosaur Pterodactylus antiquus

The beginning of the 19th century

saw the first paleontological artworks with an unambiguous scientific

basis, and this emergence coincided with paleontology being seen as a

distinct field of science. The French naturalist and professor Jean Hermann of Strasbourg, France, drafted what Witton describes as the "oldest known, incontrovertible" pieces of paleoart in 1800.

These sketches, based on the first known fossil skeleton of a

pterosaur, depict Hermann's interpretation of the animal as a flying

mammal with fur and large external ears. These ink drawings were

relatively quick sketches accompanying his notes on the fossil and were

likely never intended for publication, and their existence was only

recently uncovered from correspondence between the artist and the French

anatomist Baron Georges Cuvier.

Roman Boltunov's 1805 reconstruction of a mammoth, based on frozen carcass he observed in Siberia

Similarly, private sketches of mammoth fossils drafted by Yakutsk

merchant Roman Boltunov in 1805 were likely never intended for

scientific publication, but their function—to communicate the life

appearance of an animal whose tusks he had found in Siberia and was

hoping to sell—nevertheless establishes it one of the first examples of

paleoart by today's definition. Boltunov's sketches of the animal, which

depicted it without a trunk and boar-like, raised enough scientific interest in the specimen that the drawings were later sent to St. Petersburg and eventually led to excavation and study of the rest of the specimen.

Geologist

William Conybeare's 1822 cartoon of William Buckland in a hyena den,

intended to honor Buckland's groundbreaking analysis of fossils found at

Kirkdale cave

Cuvier went on to produce skeletal restorations of extinct mammals of

his own. Some of these included restorations with musculature layered

atop them, which in the early 1820s could be considered the earliest

examples of illustrations of animal tissue built up over fossil

skeletons. As huge and detailed fossil restorations were at this point

appearing in the same publications as these modest attempts at soft

tissue restoration, historians have speculated whether this reflected

shame and lack of interest in paleoart as being too speculative to have

scientific value at the time. One notable deviation from the Cuvier-like approach is seen in a cartoon drawn by geologist William Conybeare in 1822. This cartoon depicts paleontologist William Buckland entering the famous British Kirkdale Cave, known for its Ice Age mammal remains, amidst a scene of fossil hyenas

restored in the flesh in the ancient cave interior, the first known

artwork depicting an extinct animal restored in a rendition of an

ancient environment. A similar step forward depicts a dragon-like animal meant to represent the pterosaur Dimorphodon

flying over a coastline by George Howman; this 1829 watercolor painting

was a fanciful piece that, albeit being not particularly scientific,

was another very early attempt at restoring a fossil animal in a

suitable habitat.

Geologist Henry De la Beche's 1830 watercolor painting Duria Antiquior - A more Ancient Dorset, based on fossils found by Mary Anning

In 1830, the first "fully realized" paleoart scene, depicting

prehistoric animals in a realistic geological setting, was painted by

British paleontologist Henry De la Beche. Dubbed Duria Antiquior — A more Ancient Dorset, this watercolor painting represents a scene from the Early Jurassic of Dorset,

a fossil-rich region of the British Isles. This painting, based on

fossil discoveries along the coast of Dorset by paleontologist Mary Anning,

showcased realistic aspects of fossil animal appearance, behavior, and

environment at a level of detail, realism and accuracy that was among

the very first of its kind. This watercolor, an early illustration of paleoecology, shows plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs

swimming and foraging in a natural setting, and includes depictions of

behavior of these marine reptiles that, while unknown, were inferences

made by De la Beche based on the behavior of living animals. For

example, one ichthyosaur is painted with its mouth open about to swallow

the fish head-first, just as a predatory fish would swallow another.

Several of these animals are also depicted defecating, a theme that

emerges in other works by De la Beche. For example, his 1829 lithograph

called A Coprolitic Vision,

perhaps inspired by Conybeare's Kirkdale Cave cartoon, again pokes fun

at William Buckland by placing him at the mouth of a cave surrounded by

defecating prehistoric animals. Several authors have remarked on De la

Beche's apparent interest in fossilized feces, speculating that even the

shape of the cave in this cartoon is reminiscent of the interior of an

enormous digestive tract. In any case, Duria Antiquior inspired many subsequent derivatives, one of which was produced by Nicholas Christian Hohe in 1831 titled Jura Formation. This piece, published by German paleontologist Georg August Goldfuss,

was the first full paleoart scene to enter scientific publication, and

was likely an introduction to other academics of the time to the

potential of paleoart.

Goldfuss was the first to describe fur-like integument on a pterosaur,

which was restored in his commissioned 1831 illustration based on his

observation of the holotype specimen of Scaphognathus. This observation, which was rejected by scientists such as Hermann von Meyer, was later vindicated with certainty by 21st-century imaging technology, such as reflectance transformation imaging, used on this specimen.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's 1850s sculptures of an Iguanodon pair, some of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The role of art in disseminating paleontological knowledge took on a

new salience as dinosaur illustration advanced alongside dinosaur

paleontology in the mid-1800s. With only fragmentary fossil remains

known at the time the term "dinosaur" was coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1841, the question of life appearance of dinosaurs captured the interest of scientist and public alike.

Because of the newness and the limitations of the fossil evidence

available at the time, artists and scientists had no frame of reference

to draw upon in understanding what dinosaurs looked like in life. For

this reason, depictions of dinosaurs at the time were heavily based on

living animals such as frogs, lizards, and kangaroos. One of the most

famous examples, Iguanodon, was depicted as a resembling a huge iguana because the only known fossils of the dinosaur—the jaws and teeth—were thought to resemble those of the living lizard. With Owen's help, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

created the first life-size sculptures depicting dinosaurs and other

prehistoric animals as he thought they may have appeared; he is

considered by some to be the first significant artist to apply his

skills to the field of dinosaur paleontology. Some of these models were initially created for the Great Exhibition of 1851, but 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, in South London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow concrete Iguanodon on New Year's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Gideon Mantell had realized that Iguanodon, of which he was the discoverer, was not a heavy, pachyderm-like

animal, as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs; his

death left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, and so Owen's vision of dinosaurs became that seen by the public. He had nearly two dozen life-sized sculptures of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete sculpted over a steel and brick framework; two Iguanodon, one standing and one resting on its belly, were included.

The dinosaurs remain in place in the park, but their depictions are now

outdated as a consequence both of paleontological progress and of

Owen's own misconceptions.

Édouard Riou's 1865 illustration of Iguanodon and Megalosaurus engaged in combat, from La Terre Avant le Deluge

The Crystal Palace models, despite their inaccuracy by today's

standards, were a landmark in the advancement of paleoart as not only a

serious academic undertaking, but also one that can capture the interest

of the general public. The Crystal Palace dinosaur models were the

first works of paleoart to be merchandised as postcards, guide books,

and replicas to the general public.

In the latter half of the 1800s, this major shift could be seen in

other developments taking place in academic books and paintings

featuring scientific restorations of prehistoric life. For example, a

book by French scientist Louis Figuier titled La Terre Avant le Deluge,

published in 1863, was the first to feature a series of works of

paleoart documenting life through time. Illustrated by French painter Édouard Riou,

this book featured iconic scenes of dinosaurs and other prehistoric

animals based on Owen's constructions, and would establish a template

for academic books featuring artworks of prehistoric life through time

for years to come.

"Classic" paleoart (1890–1970)

As the western frontier

was further opened up in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the

rapidly increasing pace of dinosaur discoveries in the bone-rich

badlands of the American Midwest

and the Canadian wilderness brought with it a renewed interest in

artistic reconstructions of paleontological findings. This "classic"

period saw the emergence of Charles R. Knight, Rudolph Zallinger, and Zdeněk Burian

as the three most prominent exponents of paleoart. During this time,

dinosaurs were popularly reconstructed as tail-dragging, cold-blooded,

sluggish "Great Reptiles" that became a byword for evolutionary failure

in the minds of the public.

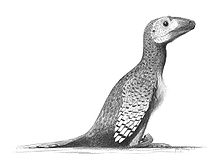

Smilodon by Charles R. Knight (1903)

Charles Knight is generally considered one of the key figures in paleoart during this time. His birth three years after Charles Darwin's publication of the influential Descent of Man, along with the "Bone Wars" between rival American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Marsh

raging during his childhood, had poised Knight for rich early

experiences in developing an interest in reconstructing prehistoric

animals. As an avid wildlife artist who disdained drawing from mounts or

photographs, instead preferring to draw from life, Knight grew up

drawing living animals, but turned toward prehistoric animals against

the backdrop of rapidly-expanding paleontological discoveries and the

public energy that accompanied the sensationalist coverage of these

discoveries around the turn of the 20th century. Knight's foray into paleoart can be traced to a commission ordered by Dr. Jacob Wortman in 1894 of a painting of a prehistoric pig, Elotherium, to accompany its fossil display at the American Museum of Natural History.

Knight, who had always preferred to draw animals from life, applied his

knowledge of modern pig anatomy to the painting, which so thrilled

Wortman that the museum then commissioned Knight to paint a series of watercolors of various fossils on display.

Entelodon (then known as Elotherium), the first commissioned restoration of an extinct animal by Charles R. Knight

Throughout the 1920s, '30s and '40s, Knight went on produce drawings,

paintings and murals of dinosaurs, early man, and extinct mammals for

the American Museum of Natural History, where he was mentored by Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Chicago's Field Museum, as well as for National Geographic and many other major magazines of the time, culminating in his last major mural for the Everhart Museum of Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1951. Biologist Stephen Jay Gould

later remarked on the depth and breadth of influence that Knight's

paleoart had on shaping public perception of extinct animals, even

without having published original research in the field. Gould described

Knight's contribution to scientific understanding in his 1989 book Wonderful Life:

"Not since the Lord himself showed his stuff to Ezekiel in the valley

of dry bones had anyone shown such grace and skill in the reconstruction

of animals from disarticulated skeletons. Charles R. Knight, the most

celebrated of artists in the reanimation of fossils, painted all the

canonical figures of dinosaurs that fire our fear and imagination to

this day". One of Knight's most famous pieces was his Leaping Laelaps,

which he produced for the American Museum of Natural History in 1897.

This painting was one of the few works of paleoart produced before 1960

to depict dinosaurs as active, fast-moving creatures, anticipating the

next era of paleontological artworks informed by the Dinosaur Renaissance.

Still of Triceratops from the 1925 film The Lost World

Illustration of Triceratops created in 1904 by Charles R. Knight

Knight's illustrations also had a large and long-lasting influence on

the depiction of prehistoric animals in popular culture. The earliest

depictions of dinosaurs in movies, such as the 1933 King Kong film and the 1925 production of The Lost World, based on the Arthur Conan Doyle novel

of the same name, relied heavily on Knight's dinosaur paintings to

produce suitable dinosaur models that were realistic for the time. The

special effects artist Ray Harryhausen would continue basing his movie dinosaurs on Knight illustrations up through the sixties, including for films such as the 1966 One Million Years B.C. and the 1969 Valley of Gwangi.

Rudolph Zallinger and Zdeněk Burian both went on to influence the

state of dinosaur art while Knight's career began to wind down.

Zallinger, a Russia-born American painter, began working for the Yale Peabody Museum illustrating marine algae around the time that the United States entered World War II. He began his most iconic piece of paleoart, a five-year mural project for the Yale Peabody Museum, in 1942. This mural, titled The Age of Reptiles, was completed in 1947 and became representative of the modern consensus of dinosaur biology at that time. He later completed a second great mural for the Peabody, The Age of Mammals, which grew out of a painting published in Life magazine in 1953.

Zdeněk Burian, working from his native Czechoslovakia,

followed the school of Knight and Zallinger, entering modern,

biologically-informed paleoart scene via his extensive series of

prehistoric life illustrations.

Burian entered the world of prehistoric illustration in the early 1930s

with illustrations for fictional books set in various prehistoric times

by amateur archaeologist Eduard Štorch. These illustrations brought him to the attention of paleontologist Josef Augusta, with whom Burian worked in cooperation from 1935 until Augusta's death in 1968. This collaboration led ultimately to the launching of Burian's career in paleoart.

Gerhard Heilmann's hypothesized bird ancestor "Proavis" (1916)

Some authors have remarked on a darker, more sinister feel to his

paleoart than that of his contemporaries, speculating that this style

was informed by Burian's experience producing artwork in his native

Czechoslovakia during World War II and, afterwards, under Soviet

control. His depictions of suffering, death, and the harsh realities of

survival that emerged as themes in his paleoart were unique at the time. Original Burian paintings are on exhibit at the Dvůr Králové Zoo, the National Museum (Prague) and at the Anthropos Museum in Brno. In 2017, the first valid Czech dinosaur was named Burianosaurus augustai in honor of both Burian and Josef Augusta.

While Charles Knight, Rudolph Zallinger and Zdeněk Burian

dominated the landscape of "classic" scientific paleoart in the first

half of the 20th century, they were far from the only paleoartists

working at this time. German landscape painter Heinrich Harder was illustrating natural history articles, including a series accompanying articles by science writer Wilhelm Bölsche on earth history for Die Gartenlaube,

a weekly magazine, in 1906 and 1908. He also worked with Bölsche to

illustrate 60 dinosaur and other prehistoric animal collecting cards for

the Reichardt Cocoa Company, titled "Tiere der Urwelt" ("Animals of the

Prehistoric World"). One of Harder's contemporaries, Danish paleontologist Gerhard Heilmann, produced a large number of sketches and ink drawings related to Archaeopteryx and avian evolution, culminating in his lavishly illustrated and controversial treatise The Origin of Birds, published in 1926.

The Dinosaur Renaissance (1970–2010)

This

classic depiction of dinosaurs remained the status quo until the 1960s,

when a minor scientific revolution began changing the perceptions of

dinosaurs as tail-dragging, sluggish animals to active, alert creatures. This reformation took place following the 1964 discovery of Deinonychus by paleontologist John Ostrom.

Ostrom's description of this nearly-complete birdlike dinosaur,

published in 1969, challenged the presupposition of dinosaurs as

cold-blooded, slow-moving reptiles, instead finding that many of these

animals were likely reminiscent of birds, not just in evolutionary

history and classification but in appearance and behavior as well. This

idea had been advanced before, most notably by 1800s English biologist Thomas Huxley about the link between dinosaurs, modern birds, and the then-newly discovered Archaeopteryx. With the discovery and description of Deinonychus,

however, Ostrom had laid out the strongest evidence yet of the close

link between birds and dinosaurs. The artistic reconstructions of Deinonychus by his student, Robert Bakker, remain iconic of what came to be known as the Dinosaur Renaissance.

Bakker's influence during this period on then-fledgling paleoartists, such as Gregory S. Paul,

as well as on public consciousness brought about a paradigm shift in

how dinosaurs were perceived by artist, scientist and layman alike. The

science and public understanding of dinosaur biology became charged by

Bakker's innovative and often controversial ideas and portrayals,

including the idea that dinosaurs were in fact warm-blooded animals like mammals and birds. Bakker's drawings of Deinonychus

and other dinosaurs depicted the animals leaping, running, and

charging, and his novel artistic output was accompanied by his writings

on paleobiology, with his influential and well-known book The Dinosaur Heresies, published in 1986, now regarded as a classic.

American scientist-artist Gregory Paul, working originally as Bakker's

student in the 1970s, became one of the leading illustrators of

prehistoric reptiles in the 1980s and has been described by some authors

as the paleoartist who may "define modern paleoart more than any

other."

Paul is notable for his 'rigorous' approach to paleoartistic

restorations, including his multi-view skeletal reconstructions,

evidence-driven studies of musculature and soft tissue, and his

attention to biomechanics to ensure realistic poses and gaits of his

artistic subjects. The artistic innovation that Paul brought to the

field of paleoart is to prioritize detail over atmosphere, leading to

some criticism of his work as being 'flat' or lacking in depth, but also

to imbue dinosaur depictions with a greater variety of naturalistic

coloration and patterns, whereas most dinosaur coloration in artworks

beforehand had been fairly drab and uniform.

Cast of Tyrannosaurus rex specimen AMNH 5027 mounted in a "leaping posture" by Robert Bakker at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science

Ostrom, Bakker and Paul changed the landscape of depictions of

prehistoric animals in science and popular culture alike throughout the

1970s, '80s and '90s. Their influence affected the presentation of

museum displays throughout the world and eventually found its way into

popular culture, with the climax of this period perhaps best marked by

the 1990 novel and 1993 film Jurassic Park.

Paul in particular helped set the stage for the next wave of

paleoaristry, and from the 1970s to the end of the twentieth century,

paleoartists working from the 'rigorous' approach included Douglas Henderson, Mark Hallett, Michael Skrepnick, William Stout, Ely Kish, Luis Rey, John Gurche, Bob Walters, and others, including an expanding body of sculpting work led by artists such as Brian Cooley, Stephen Czerkas, and Dave Thomas.

Many of these artists developed unique and lucrative stylistic niches

without sacrificing their rigorous approach, such as Douglas Henderson's

detailed and atmospheric landscapes, and Luis Rey's brightly-colored,

"extreme" depictions.

The "Renaissance" movement so revolutionized paleoart that even the

last works of Burian, a master of the "classic" age, were thought to be

influenced by the newfangled preference for active, dynamic, exciting

depictions of dinosaurs.

This movement was working in parallel with great strides in the

scientific progress of vertebrate paleontology that were occurring

during this time. Precision in anatomy and artistic reconstruction was

aided by an increasingly detailed and sophisticated understanding of

these extinct animals through new discoveries and interpretations that

pushed paleoart into more objective territory with respect to accuracy. For example, the feathered dinosaur revolution, facilitated by unprecedented discoveries in the Liaoning province of northern China in the late 1990s and early 2000s, was perhaps foreseen by artist Sarah Landry, who drew the first feathered dinosaur for Bakker's seminal Scientific American

article in 1975. One of the first major shows of dinosaur art was

published in 1986 by Sylvia Czerkas, along with the accompanying volume Dinosaurs Past and Present.

Modern (and post-modern) paleoart (2010–present)

Birdlike illustration of feathered Deinonychus by John Conway, 2006

Although various authors are in agreement about the events that

caused the beginning of the Dinosaur Renaissance, the transition to the

modern age of paleoart has been more gradual, with differing attitudes

about what typifies the demarcation. Gregory Paul's high-fidelity archosaur

skeletal reconstructions provided a basis for ushering in the modern

age of paleoart, which is perhaps best characterized by adding

speculative flair to the rigorous, anatomically-conscious approach

popularized by the Dinosaur Renaissance. Novel advances in paleontology,

such as new feathered dinosaur discoveries and the various pigmentation studies of dinosaur integument that began around 2010, have become representative of paleoart after the turn of the millennium. Witton (2018) characterizes the modern movement with the rise of digital art,

as well as the establishment of an internet community that would

enabled paleoartists and enthusiasts to network, share digitized and open access

scientific resources, and to build a global community that was

unprecedented until the first decade of the twenty-first century. The

continuum of work leading from the themes and advances that began in the

Dinosaur Renaissance to the production of modern paleoart is showcased

in several books that were published post-2010, such as Steve White's Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart (2012) and its "sequel", Dinosaur Art II: The Cutting Edge of Paleoart (2017).

Pair of azhdarchid pterosaurs Arambourgiania, by Mark Witton, 2017

Although this transition was gradual, this period has been described

as a salient cultural phenomenon that came about largely as a

consequence of this increased connectivity and access to paleoart

brought by the digital age. The saturation of paleoart with established

and overused heuristics, many of which had been established by

paleoartists working in the height of the revolution that came before,

led to an increased awareness and criticism of the repetitive and

unimaginative use of ideas that were, by the first decade of the 21st

century, lacking in novelty. This observation led to a movement

characterized by the idea that prehistoric animals could be shown in

artworks engaging in a greater range of behaviors, habitats, styles,

compositions, and interpretations of life appearance than had been

imagined in paleoart up to that point, but without violating the

principles of anatomical and scientific rigor that had been established

by the paleoart revolution that came before.

Additionally, the traditional heuristics used in paleoart up to this

point were shown to produce illustrations of modern animals that failed

to depict these accurately. These ideas were formalized in a 2012 book by paleoartists John Conway and Memo Koseman, along with paleontologist Darren Naish, called All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals.

This book and its associated minor paradigm shift, commonly referred to

as the "All Yesterdays" movement, argued that it was better to employ

scientifically rigorous "reasoned speculation" to produce a greater

range of speculative, but plausible, reconstructions of prehistoric

animals. Conway and colleagues argued that the range of appearances and

behaviors depicted in paleoart had only managed to capture a very narrow

range of what's plausible, based on the limited data available, and

that artistic approaches to these depictions had become "overly steeped

in tradition." For example, All Yesterdays examines the small, four-winged dromaeosaur Microraptor

in this context. This dinosaur, described in 2003, has been depicted by

countless paleoartists as a "strange, dragon-like feathered glider with

a reptilian face". Conway's illustration of Microraptor in All Yesterdays

attempts to restore the animal "from scratch" without influence from

these popular reconstructions, instead depicting it as a naturalistic,

birdlike animal perched at its nest.

Despite the importance of the "All Yesterdays" movement in

hindsight, the book itself argued that the modern conceptualization of

paleoart was based on anatomically rigorous restorations that came

alongside and subsequent to Paul, including those who experimented with

these principles outside of archosaurs. For example, artists that

pioneered anatomically rigorous reconstructions of fossil hominids, like Jay Matternes and Alfons and Adrie Kennis, as well fossil mammal paleoartist Mauricio Antón,

were lauded by Conway and colleagues as seminal influences in the new

culture of paleoart. Other modern paleoartists of the "anatomically

rigorous" and "All Yesterdays" movement include Jason Brougham, Mark Hallett, Scott Hartman, Bob Nicholls, Emily Willoughby and Mark P. Witton.

Other authors write in agreement that the modern paleoart movement

incorporates an element of "challenging tropes and the status quo" and

that paleoart has "entered its experimental phase" as of the dawn of the

21st century.

A 2013 study found that older paleoart was still influential in

popular culture long after new discoveries made them obsolete. This was

explained as cultural inertia.

In a 2014 paper, Mark Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway outlined

the historical significance of paleoart, and criticized the

over-reliance on clichés and the "culture of copying" they saw to be

problematic in the field at the time. This tendency to copy "memes"

established and proliferated by others in the field is thought to have

been a stimulus for the "All Yesterdays" movement of injecting

originality back into paleoart.

Recognition

Since 1999, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has awarded the John J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize

for achievement in the field. The society says that paleoart "is one of

the most important vehicles for communicating discoveries and data

among paleontologists, and is critical to promulgating vertebrate

paleontology across disciplines and to lay audiences". The SVP is also

the site of the occasional/annual "PaleoArt Poster Exhibit", a juried poster show at the opening reception of the annual SVP meetings.

Paleoart has enjoyed increasing exposure in globally recognized contests and exhibits. The Museu da Lourinhã organizes the annual International Dinosaur Illustration Contest for promoting the art of dinosaur and other fossils. In fall of 2018, the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science of Albuquerque, New Mexico, displayed a juried show of paleoart called "Picturing the Past".[105]

This show includes 87 works by 46 paleoartists from 15 countries, and

features one of the largest and most diverse collections of prehistoric

animals, settings, themes and styles.

In addition to contests and art exhibitions, paleoart continues

to play a significant role in public understanding of paleontology in a

variety of ways. In 2007, The Children's Museum of Indianapolis

released a lesson plan on paleoart for children of grades 3 to 5 that

uses paleoart as a way to introduce children to paleontology.

Paleontological-themed merchandise has been around since at least the

mid-1800s, but the popularity of anatomically-accurate and

paleoart-based merchandise is relatively novel, such as Rebecca Groom's

highly accurate plush toy reconstructions of extinct animals.