In computability theory, the Church–Turing thesis (also known as computability thesis, the Turing–Church thesis, the Church–Turing conjecture, Church's thesis, Church's conjecture, and Turing's thesis) is a hypothesis about the nature of computable functions. It states that a function on the natural numbers can be calculated by an effective method if and only if it is computable by a Turing machine. The thesis is named after American mathematician Alonzo Church and the British mathematician Alan Turing. Before the precise definition of computable function, mathematicians often used the informal term effectively calculable to describe functions that are computable by paper-and-pencil methods. In the 1930s, several independent attempts were made to formalize the notion of computability:

On the other hand, the Church–Turing thesis states that the above three formally-defined classes of computable functions coincide with the informal notion of an effectively calculable function. Since, as an informal notion, the concept of effective calculability does not have a formal definition, the thesis, although it has near-universal acceptance, cannot be formally proven.

Since its inception, variations on the original thesis have arisen, including statements about what can physically be realized by a computer in our universe (physical Church-Turing thesis) and what can be efficiently computed (Church–Turing thesis (complexity theory)). These variations are not due to Church or Turing, but arise from later work in complexity theory and digital physics. The thesis also has implications for the philosophy of mind.

- In 1933, Kurt Gödel, with Jacques Herbrand, created a formal definition of a class called general recursive functions. The class of general recursive functions is the smallest class of functions (possibly with more than one argument) which includes all constant functions, projections, the successor function, and which is closed under function composition, recursion, and minimization.

- In 1936, Alonzo Church created a method for defining functions called the λ-calculus. Within λ-calculus, he defined an encoding of the natural numbers called the Church numerals. A function on the natural numbers is called λ-computable if the corresponding function on the Church numerals can be represented by a term of the λ-calculus.

- Also in 1936, before learning of Church's work, Alan Turing created a theoretical model for machines, now called Turing machines, that could carry out calculations from inputs by manipulating symbols on a tape. Given a suitable encoding of the natural numbers as sequences of symbols, a function on the natural numbers is called Turing computable if some Turing machine computes the corresponding function on encoded natural numbers.

On the other hand, the Church–Turing thesis states that the above three formally-defined classes of computable functions coincide with the informal notion of an effectively calculable function. Since, as an informal notion, the concept of effective calculability does not have a formal definition, the thesis, although it has near-universal acceptance, cannot be formally proven.

Since its inception, variations on the original thesis have arisen, including statements about what can physically be realized by a computer in our universe (physical Church-Turing thesis) and what can be efficiently computed (Church–Turing thesis (complexity theory)). These variations are not due to Church or Turing, but arise from later work in complexity theory and digital physics. The thesis also has implications for the philosophy of mind.

Statement in Church's and Turing's words

J. B. Rosser (1939)

addresses the notion of "effective computability" as follows: "Clearly

the existence of CC and RC (Church's and Rosser's proofs) presupposes a

precise definition of 'effective'. 'Effective method' is here used in

the rather special sense of a method each step of which is precisely

predetermined and which is certain to produce the answer in a finite

number of steps".

Thus the adverb-adjective "effective" is used in a sense of "1a:

producing a decided, decisive, or desired effect", and "capable of

producing a result".

In the following, the words "effectively calculable" will mean

"produced by any intuitively 'effective' means whatsoever" and

"effectively computable" will mean "produced by a Turing-machine or

equivalent mechanical device". Turing's "definitions" given in a

footnote in his 1938 Ph.D. thesis Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals, supervised by Church, are virtually the same:

† We shall use the expression "computable function" to mean a function calculable by a machine, and let "effectively calculable" refer to the intuitive idea without particular identification with any one of these definitions.

The thesis can be stated as: Every effectively calculable function is a computable function.

Turing stated it this way:

It was stated ... that "a function is effectively calculable if its values can be found by some purely mechanical process". We may take this literally, understanding that by a purely mechanical process one which could be carried out by a machine. The development ... leads to ... an identification of computability† with effective calculability. [† is the footnote quoted above.]

History

One of the important problems for logicians in the 1930s was the Entscheidungsproblem of David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann,

which asked whether there was a mechanical procedure for separating

mathematical truths from mathematical falsehoods. This quest required

that the notion of "algorithm" or "effective calculability" be pinned

down, at least well enough for the quest to begin. But from the very outset Alonzo Church's attempts began with a debate that continues to this day. Was the notion of "effective calculability" to be (i) an "axiom or axioms" in an axiomatic system, (ii) merely a definition that "identified" two or more propositions, (iii) an empirical hypothesis to be verified by observation of natural events, or (iv) just a proposal for the sake of argument (i.e. a "thesis").

Circa 1930–1952

In the course of studying the problem, Church and his student Stephen Kleene introduced the notion of λ-definable functions, and they were able to prove that several large classes of functions frequently encountered in number theory were λ-definable.

The debate began when Church proposed to Gödel that one should define

the "effectively computable" functions as the λ-definable functions.

Gödel, however, was not convinced and called the proposal "thoroughly

unsatisfactory". Rather, in correspondence with Church (c. 1934–35), Gödel proposed axiomatizing the notion of "effective calculability"; indeed, in a 1935 letter to Kleene, Church reported that:

His [Gödel's] only idea at the time was that it might be possible, in terms of effective calculability as an undefined notion, to state a set of axioms which would embody the generally accepted properties of this notion, and to do something on that basis.

But Gödel offered no further guidance. Eventually, he would suggest

his recursion, modified by Herbrand's suggestion, that Gödel had

detailed in his 1934 lectures in Princeton NJ (Kleene and Rosser transcribed the notes). But he did not think that the two ideas could be satisfactorily identified "except heuristically".

Next, it was necessary to identify and prove the equivalence of

two notions of effective calculability. Equipped with the λ-calculus and

"general" recursion, Stephen Kleene with help of Church and J. Barkley Rosser

produced proofs (1933, 1935) to show that the two calculi are

equivalent. Church subsequently modified his methods to include use of

Herbrand–Gödel recursion and then proved (1936) that the Entscheidungsproblem is unsolvable: there is no algorithm that can determine whether a well formed formula has a "normal form.

Many years later in a letter to Davis (c. 1965), Gödel said that

"he was, at the time of these [1934] lectures, not at all convinced that

his concept of recursion comprised all possible recursions".

By 1963–64 Gödel would disavow Herbrand–Gödel recursion and the

λ-calculus in favor of the Turing machine as the definition of

"algorithm" or "mechanical procedure" or "formal system".

A hypothesis leading to a natural law?: In late 1936 Alan Turing's paper (also proving that the Entscheidungsproblem is unsolvable) was delivered orally, but had not yet appeared in print. On the other hand, Emil Post's 1936 paper had appeared and was certified independent of Turing's work. Post strongly disagreed with Church's "identification" of effective computability with the λ-calculus and recursion, stating:

Actually the work already done by Church and others carries this identification considerably beyond the working hypothesis stage. But to mask this identification under a definition… blinds us to the need of its continual verification.

Rather, he regarded the notion of "effective calculability" as merely a "working hypothesis" that might lead by inductive reasoning to a "natural law" rather than by "a definition or an axiom". This idea was "sharply" criticized by Church.

Thus Post in his 1936 paper was also discounting Kurt Gödel's suggestion to Church in 1934–35 that the thesis might be expressed as an axiom or set of axioms.

Turing adds another definition, Rosser equates all three: Within just a short time, Turing's 1936–37 paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem"

appeared. In it he stated another notion of "effective computability"

with the introduction of his a-machines (now known as the Turing machine

abstract computational model). And in a proof-sketch added as an

"Appendix" to his 1936–37 paper, Turing showed that the classes of

functions defined by λ-calculus and Turing machines coincided.

Church was quick to recognise how compelling Turing's analysis was. In

his review of Turing's paper he made clear that Turing's notion made

"the identification with effectiveness in the ordinary (not explicitly

defined) sense evident immediately".

In a few years (1939) Turing would propose, like Church and Kleene before him, that his formal definition of mechanical computing agent was the correct one. Thus, by 1939, both Church (1934) and Turing (1939) had individually proposed that their "formal systems" should be definitions of "effective calculability"; neither framed their statements as theses.

Rosser (1939) formally identified the three notions-as-definitions:

All three definitions are equivalent, so it does not matter which one is used.

Kleene proposes Church's Thesis: This left the overt expression of a "thesis" to Kleene. In his 1943 paper Recursive Predicates and Quantifiers Kleene proposed his "THESIS I":

This heuristic fact [general recursive functions are effectively calculable] ... led Church to state the following thesis. The same thesis is implicit in Turing's description of computing machines.

THESIS I. Every effectively calculable function (effectively decidable predicate) is general recursive [Kleene's italics]Since a precise mathematical definition of the term effectively calculable (effectively decidable) has been wanting, we can take this thesis ... as a definition of it ...

references Church 1936; references Turing 1936–7

Kleene goes on to note that:

the thesis has the character of an hypothesis—a point emphasized by Post and by Church. If we consider the thesis and its converse as definition, then the hypothesis is an hypothesis about the application of the mathematical theory developed from the definition. For the acceptance of the hypothesis, there are, as we have suggested, quite compelling grounds.

Kleene's Church–Turing Thesis: A few years later (1952)

Kleene, who switched from presenting his work in the mathematical

terminology of the lambda calculus of his phd advisor Alonzo Church to

the theory of general recursive functions of his other teacher Kurt

Gödel, would overtly name the Church–Turing thesis in his correction of

Turing's paper "The Word Problem in Semi-Groups with Cancellation", defend, and express the two "theses" and then "identify" them (show equivalence) by use of his Theorem XXX:

Heuristic evidence and other considerations led Church 1936 to propose the following thesis.

Thesis I. Every effectively calculable function (effectively decidable predicate) is general recursive.Theorem XXX: The following classes of partial functions are coextensive, i.e. have the same members: (a) the partial recursive functions, (b) the computable functions ...

Turing's thesis: Turing's thesis that every function which would naturally be regarded as computable is computable under his definition, i.e. by one of his machines, is equivalent to Church's thesis by Theorem XXX.

Later developments

An attempt to understand the notion of "effective computability" better led Robin Gandy (Turing's student and friend) in 1980 to analyze machine computation (as opposed to human-computation acted out by a Turing machine). Gandy's curiosity about, and analysis of, cellular automata (including Conway's game of life),

parallelism, and crystalline automata, led him to propose four

"principles (or constraints) ... which it is argued, any machine must

satisfy".

His most-important fourth, "the principle of causality" is based on the

"finite velocity of propagation of effects and signals; contemporary

physics rejects the possibility of instantaneous action at a distance".

From these principles and some additional constraints—(1a) a lower

bound on the linear dimensions of any of the parts, (1b) an upper bound

on speed of propagation (the velocity of light), (2) discrete progress

of the machine, and (3) deterministic behavior—he produces a theorem

that "What can be calculated by a device satisfying principles I–IV is

computable."

In the late 1990s Wilfried Sieg

analyzed Turing's and Gandy's notions of "effective calculability" with

the intent of "sharpening the informal notion, formulating its general

features axiomatically, and investigating the axiomatic framework". In his 1997 and 2002 work Sieg presents a series of constraints on the behavior of a computor—"a human computing agent who proceeds mechanically". These constraints reduce to:

- "(B.1) (Boundedness) There is a fixed bound on the number of symbolic configurations a computor can immediately recognize.

- "(B.2) (Boundedness) There is a fixed bound on the number of internal states a computor can be in.

- "(L.1) (Locality) A computor can change only elements of an observed symbolic configuration.

- "(L.2) (Locality) A computor can shift attention from one symbolic configuration to another one, but the new observed configurations must be within a bounded distance of the immediately previously observed configuration.

- "(D) (Determinacy) The immediately recognizable (sub-)configuration determines uniquely the next computation step (and id [instantaneous description])"; stated another way: "A computor's internal state together with the observed configuration fixes uniquely the next computation step and the next internal state."

The matter remains in active discussion within the academic community.

The thesis as a definition

The

thesis can be viewed as nothing but an ordinary mathematical

definition. Comments by Gödel on the subject suggest this view, e.g.

"the correct definition of mechanical computability was established

beyond any doubt by Turing". The case for viewing the thesis as nothing more than a definition is made explicitly by Robert I. Soare,

where it is also argued that Turing's definition of computability is no

less likely to be correct than the epsilon-delta definition of a continuous function.

Success of the thesis

Other formalisms (besides recursion, the λ-calculus, and the Turing machine) have been proposed for describing effective calculability/computability. Stephen Kleene (1952) adds to the list the functions "reckonable in the system S1" of Kurt Gödel 1936, and Emil Post's (1943, 1946) "canonical [also called normal] systems". In the 1950s Hao Wang and Martin Davis greatly simplified the one-tape Turing-machine model (see Post–Turing machine). Marvin Minsky expanded the model to two or more tapes and greatly simplified the tapes into "up-down counters", which Melzak and Lambek further evolved into what is now known as the counter machine model. In the late 1960s and early 1970s researchers expanded the counter machine model into the register machine, a close cousin to the modern notion of the computer. Other models include combinatory logic and Markov algorithms. Gurevich adds the pointer machine

model of Kolmogorov and Uspensky (1953, 1958): "... they just wanted

to ... convince themselves that there is no way to extend the notion of

computable function."

All these contributions involve proofs that the models are

computationally equivalent to the Turing machine; such models are said

to be Turing complete.

Because all these different attempts at formalizing the concept of

"effective calculability/computability" have yielded equivalent results,

it is now generally assumed that the Church–Turing thesis is correct.

In fact, Gödel (1936) proposed something stronger than this; he observed

that there was something "absolute" about the concept of "reckonable in

S1":

It may also be shown that a function which is computable ['reckonable'] in one of the systems Si, or even in a system of transfinite type, is already computable [reckonable] in S1. Thus the concept 'computable' ['reckonable'] is in a certain definite sense 'absolute', while practically all other familiar metamathematical concepts (e.g. provable, definable, etc.) depend quite essentially on the system to which they are defined ...

Informal usage in proofs

Proofs

in computability theory often invoke the Church–Turing thesis in an

informal way to establish the computability of functions while avoiding

the (often very long) details which would be involved in a rigorous,

formal proof.

To establish that a function is computable by Turing machine, it is

usually considered sufficient to give an informal English description of

how the function can be effectively computed, and then conclude "by the

Church–Turing thesis" that the function is Turing computable

(equivalently, partial recursive).

Dirk van Dalen gives the following example for the sake of illustrating this informal use of the Church–Turing thesis:

EXAMPLE: Each infinite RE set contains an infinite recursive set.

Proof: Let A be infinite RE. We list the elements of A effectively, n0, n1, n2, n3, ...

From this list we extract an increasing sublist: put m0=n0, after finitely many steps we find an nk such that nk > m0, put m1=nk. We repeat this procedure to find m2 > m1, etc. this yields an effective listing of the subset B={m0,m1,m2,...} of A, with the property mi < mi+1.

Claim. B is decidable. For, in order to test k in B we must check if k=mi for some i. Since the sequence of mi's is increasing we have to produce at most k+1 elements of the list and compare them with k. If none of them is equal to k, then k not in B. Since this test is effective, B is decidable and, by Church's thesis, recursive.

In order to make the above example completely rigorous, one would

have to carefully construct a Turing machine, or λ-function, or

carefully invoke recursion axioms, or at best, cleverly invoke various

theorems of computability theory. But because the computability theorist

believes that Turing computability correctly captures what can be

computed effectively, and because an effective procedure is spelled out

in English for deciding the set B, the computability theorist accepts

this as proof that the set is indeed recursive.

Variations

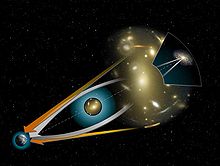

The success of the Church–Turing thesis prompted variations of the thesis to be proposed. For example, the physical Church–Turing thesis states: "All physically computable functions are Turing-computable."

The

Church–Turing thesis says nothing about the efficiency with which one

model of computation can simulate another. It has been proved for

instance that a (multi-tape) universal Turing machine only suffers a logarithmic slowdown factor in simulating any Turing machine.

A variation of the Church–Turing thesis addresses whether an

arbitrary but "reasonable" model of computation can be efficiently

simulated. This is called the feasibility thesis, also known as the (classical) complexity-theoretic Church–Turing thesis or the extended Church–Turing thesis, which is not due to Church or Turing, but rather was realized gradually in the development of complexity theory. It states: "A probabilistic Turing machine can efficiently simulate any realistic model of computation." The word 'efficiently' here means up to polynomial-time reductions. This thesis was originally called computational complexity-theoretic Church–Turing thesis by Ethan Bernstein and Umesh Vazirani

(1997). The complexity-theoretic Church–Turing thesis, then, posits

that all 'reasonable' models of computation yield the same class of

problems that can be computed in polynomial time. Assuming the

conjecture that probabilistic polynomial time (BPP) equals deterministic polynomial time (P), the word 'probabilistic' is optional in the complexity-theoretic Church–Turing thesis. A similar thesis, called the invariance thesis, was introduced by Cees F. Slot and Peter van Emde Boas. It states: "'Reasonable'

machines can simulate each other within a polynomially bounded overhead

in time and a constant-factor overhead in space." The thesis originally appeared in a paper at STOC'84, which was the first paper to show that polynomial-time overhead and constant-space overhead could be simultaneously achieved for a simulation of a Random Access Machine on a Turing machine.

If BQP is shown to be a strict superset of BPP, it would invalidate the complexity-theoretic Church–Turing thesis. In other words, there would be efficient quantum algorithms that perform tasks that do not have efficient probabilistic algorithms.

This would not however invalidate the original Church–Turing thesis,

since a quantum computer can always be simulated by a Turing machine,

but it would invalidate the classical complexity-theoretic Church–Turing

thesis for efficiency reasons. Consequently, the quantum complexity-theoretic Church–Turing thesis states: "A quantum Turing machine can efficiently simulate any realistic model of computation."

Eugene Eberbach and Peter Wegner claim that the Church–Turing thesis is sometimes interpreted too broadly,

stating "the broader assertion that algorithms precisely capture what can be computed is invalid". They claim that forms of computation not captured by the thesis are relevant today,

terms which they call super-Turing computation.

Philosophical implications

Philosophers have interpreted the Church–Turing thesis as having implications for the philosophy of mind. B. Jack Copeland

states that it is an open empirical question whether there are actual

deterministic physical processes that, in the long run, elude simulation

by a Turing machine; furthermore, he states that it is an open

empirical question whether any such processes are involved in the

working of the human brain.

There are also some important open questions which cover the

relationship between the Church–Turing thesis and physics, and the

possibility of hypercomputation. When applied to physics, the thesis has several possible meanings:

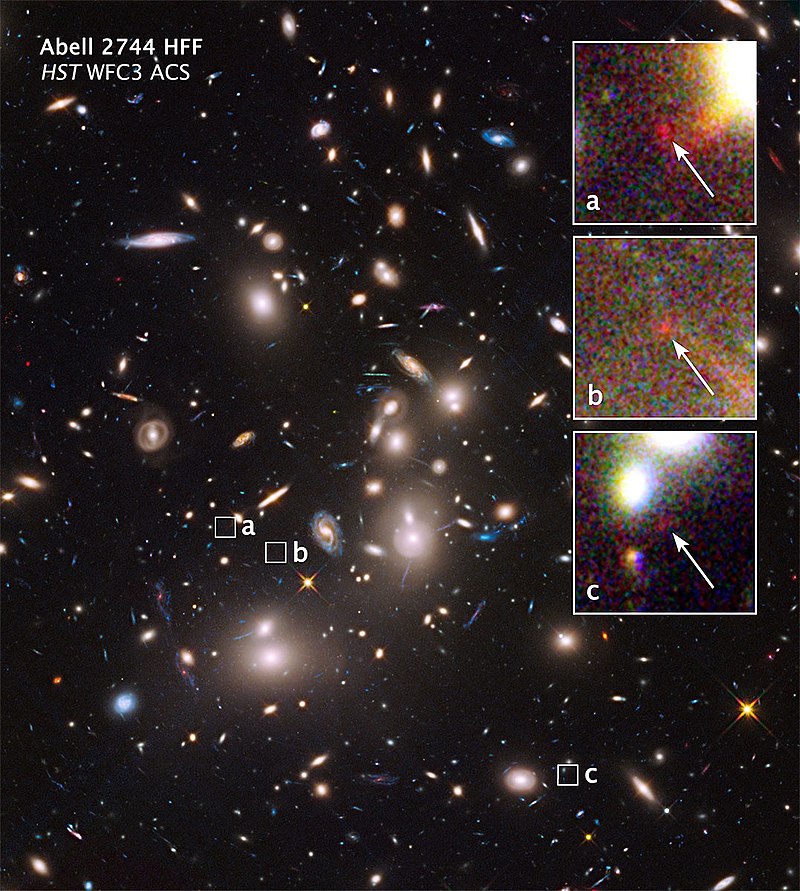

- The universe is equivalent to a Turing machine; thus, computing non-recursive functions is physically impossible. This has been termed the strong Church–Turing thesis, or Church–Turing–Deutsch principle, and is a foundation of digital physics.

- The universe is not equivalent to a Turing machine (i.e., the laws of physics are not Turing-computable), but incomputable physical events are not "harnessable" for the construction of a hypercomputer. For example, a universe in which physics involves random real numbers, as opposed to computable reals, would fall into this category.

- The universe is a hypercomputer, and it is possible to build physical devices to harness this property and calculate non-recursive functions. For example, it is an open question whether all quantum mechanical events are Turing-computable, although it is known that rigorous models such as quantum Turing machines are equivalent to deterministic Turing machines. (They are not necessarily efficiently equivalent; see above.) John Lucas and Roger Penrose have suggested that the human mind might be the result of some kind of quantum-mechanically enhanced, "non-algorithmic" computation.

There are many other technical possibilities which fall outside or

between these three categories, but these serve to illustrate the range

of the concept.

Philosophical aspects of the thesis, regarding both physical and

biological computers, are also discussed in Odifreddi's 1989 textbook on

recursion theory.

Non-computable functions

One can formally define functions that are not computable. A well-known example of such a function is the Busy Beaver function. This function takes an input n and returns the largest number of symbols that a Turing machine with n

states can print before halting, when run with no input. Finding an

upper bound on the busy beaver function is equivalent to solving the halting problem,

a problem known to be unsolvable by Turing machines. Since the busy

beaver function cannot be computed by Turing machines, the Church–Turing

thesis states that this function cannot be effectively computed by any

method.

Several computational models allow for the computation of (Church-Turing) non-computable functions. These are known as

hypercomputers.

Mark Burgin argues that super-recursive algorithms such as inductive Turing machines disprove the Church–Turing thesis.

His argument relies on a definition of algorithm broader than the

ordinary one, so that non-computable functions obtained from some

inductive Turing machines are called computable. This interpretation of

the Church–Turing thesis differs from the interpretation commonly

accepted in computability theory, discussed above. The argument that

super-recursive algorithms are indeed algorithms in the sense of the

Church–Turing thesis has not found broad acceptance within the

computability research community.