An economic bubble or asset bubble (sometimes also referred to as a speculative bubble, a market bubble, a price bubble, a financial bubble, a speculative mania, or a balloon) is a situation in which asset prices appear to be based on implausible or inconsistent views about the future. It could also be described as trade in an asset at a price or price range that strongly exceeds the asset's intrinsic value.

While some economists deny that bubbles occur, the causes of bubbles remain disputed by those who are convinced that asset prices often deviate strongly from intrinsic values.

Many explanations have been suggested, and research has recently shown that bubbles may appear even without uncertainty, speculation, or bounded rationality, in which case they can be called non-speculative bubbles or sunspot equilibria. In such cases, the bubbles may be argued to be rational, where investors at every point are fully compensated for the possibility that the bubble might collapse by higher returns. These approaches require that the timing of the bubble collapse can only be forecast probabilistically and the bubble process is often modelled using a Markov switching model. Similar explanations suggest that bubbles might ultimately be caused by processes of price coordination.

More recent theories of asset bubble formation suggest that these events are sociologically driven. For instance, explanations have focused on emerging social norms and the role that culturally-situated stories or narratives play in these events.

Because it is often difficult to observe intrinsic values in real-life markets, bubbles are often conclusively identified only in retrospect, once a sudden drop in prices has occurred. Such a drop is known as a crash or a bubble burst. In an economic bubble, prices can fluctuate erratically and become impossible to predict from supply and demand alone.

Asset bubbles are now widely regarded as a recurrent feature of modern economic history dating back as far as the 1600s. The Dutch Golden Age's Tulipmania (in the mid-1630s) is often considered the first recorded economic bubble in history.

Both the boom and the bust phases of the bubble are examples of a positive feedback mechanism (in contrast to the negative feedback mechanism that determines the equilibrium price under normal market circumstances).

History and origin of term

The term "bubble", in reference to financial crisis, originated in the 1711–1720 British South Sea Bubble, and originally referred to the companies themselves, and their inflated stock, rather than to the crisis itself. This was one of the earliest modern financial crises; other episodes were referred to as "manias", as in the Dutch tulip mania. The metaphor indicated that the prices of the stock were inflated and fragile – expanded based on nothing but air, and vulnerable to a sudden burst, as in fact occurred.

Some later commentators have extended the metaphor to emphasize the suddenness, suggesting that economic bubbles end "All at once, and nothing first, / Just as bubbles do when they burst," though theories of financial crises such as debt deflation and the Financial Instability Hypothesis suggest instead that bubbles burst progressively, with the most vulnerable (most highly-leveraged) assets failing first, and then the collapse spreading throughout the economy.

Types of bubbles

There are different types of bubbles, with economists primarily interested in two major types of bubbles:

- 1. Equity bubble

An equity bubble is characterised by tangible investments and the unsustainable desire to satisfy a legitimate market in high demand. These kind of bubbles are characterised by easy liquidity, tangible and real assets, and an actual innovation that boosts confidence. Two instances of an equity bubble are the Tulip Mania and the dot-com bubble.

- 2. Debt bubble

A debt bubble is characterised by intangible or credit based investments with little ability to satisfy growing demand in a non-existent market. These bubbles are not backed by real assets and are characterized by frivolous lending in the hopes of returning a profit or security. These bubbles usually end in debt deflation causing bank runs or a currency crisis when the government can no longer maintain the fiat currency. Examples include the Roaring Twenties stock market bubble (which caused the Great Depression) and the United States housing bubble (which caused the Great Recession). The corporate debt bubble that caused the COVID-19 recession is an example of a combined debt and equity bubble.

Impact

The impact of economic bubbles is debated within and between schools of economic thought; they are not generally considered beneficial, but it is debated how harmful their formation and bursting is.

Within mainstream economics, many believe that bubbles cannot be identified in advance, cannot be prevented from forming, that attempts to "prick" the bubble may cause financial crisis, and that instead authorities should wait for bubbles to burst of their own accord, dealing with the aftermath via monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Political economist Robert E. Wright argues that bubbles can be identified before the fact with high confidence.

In addition, the crash which usually follows an economic bubble can destroy a large amount of wealth and cause continuing economic malaise; this view is particularly associated with the debt-deflation theory of Irving Fisher, and elaborated within Post-Keynesian economics.

A protracted period of low risk premiums can simply prolong the downturn in asset price deflation as was the case of the Great Depression in the 1930s for much of the world and the 1990s for Japan. Not only can the aftermath of a crash devastate the economy of a nation, but its effects can also reverberate beyond its borders.

Effect upon spending

Another important aspect of economic bubbles is their impact on spending habits. Market participants with overvalued assets tend to spend more because they "feel" richer (the wealth effect). Many observers quote the housing market in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Spain and parts of the United States in recent times, as an example of this effect. When the bubble inevitably bursts, those who hold on to these overvalued assets usually experience a feeling of reduced wealth and tend to cut discretionary spending at the same time, hindering economic growth or, worse, exacerbating the economic slowdown.

In an economy with a central bank, the bank may therefore attempt to keep an eye on asset price appreciation and take measures to curb high levels of speculative activity in financial assets. This is usually done by increasing the interest rate (that is, the cost of borrowing money). Historically, this is not the only approach taken by central banks. It has been argued that they should stay out of it and let the bubble, if it is one, take its course.

Possible causes

In the 1970s, excess monetary expansion after the U.S. came off the gold standard (August 1971) created massive commodities bubbles. These bubbles only ended when the U.S. Central Bank (Federal Reserve) finally reined in the excess money, raising federal funds interest rates to over 14%. The commodities bubble popped and prices of oil and gold, for instance, came down to their proper levels. Similarly, low interest rate policies by the U.S. Federal Reserve in the 2001–2004 are believed to have exacerbated housing and commodities bubbles. The housing bubble popped as subprime mortgages began to default at much higher rates than expected, which also coincided with the rising of the fed funds rate.

It has also been variously suggested that bubbles may be rational, intrinsic, and contagious. To date, there is no widely accepted theory to explain their occurrence. Recent computer-generated agency models suggest excessive leverage could be a key factor in causing financial bubbles.

Puzzlingly for some, bubbles occur even in highly predictable experimental markets, where uncertainty is eliminated and market participants should be able to calculate the intrinsic value of the assets simply by examining the expected stream of dividends. Nevertheless, bubbles have been observed repeatedly in experimental markets, even with participants such as business students, managers, and professional traders. Experimental bubbles have proven robust to a variety of conditions, including short-selling, margin buying, and insider trading.

While there is no clear agreement on what causes bubbles, there is evidence to suggest that they are not caused by bounded rationality or assumptions about the irrationality of others, as assumed by greater fool theory. It has also been shown that bubbles appear even when market participants are well-capable of pricing assets correctly. Further, it has been shown that bubbles appear even when speculation is not possible or when over-confidence is absent.

More recent theories of asset bubble formation suggest that they are likely sociologically-driven events, thus explanations that merely involve fundamental factors or snippets of human behavior are incomplete at best. For instance, qualitative researchers Preston Teeter and Jorgen Sandberg argue that market speculation is driven by culturally-situated narratives that are deeply embedded in and supported by the prevailing institutions of the time. They cite factors such as bubbles forming during periods of innovation, easy credit, loose regulations, and internationalized investment as reasons why narratives play such an influential role in the growth of asset bubbles.

Liquidity

One possible cause of bubbles is excessive monetary liquidity in the financial system, inducing lax or inappropriate lending standards by the banks, which makes markets vulnerable to volatile asset price inflation caused by short-term, leveraged speculation. For example, Axel A. Weber, the former president of the Deutsche Bundesbank, has argued that "The past has shown that an overly generous provision of liquidity in global financial markets in connection with a very low level of interest rates promotes the formation of asset-price bubbles."

According to the explanation, excessive monetary liquidity (easy credit, large disposable incomes) potentially occurs while fractional reserve banks are implementing expansionary monetary policy (i.e. lowering of interest rates and flushing the financial system with money supply); this explanation may differ in certain details according to economic philosophy. Those who believe the money supply is controlled exogenously by a central bank may attribute an 'expansionary monetary policy' to said bank and (should one exist) a governing body or institution; others who believe that the money supply is created endogenously by the banking sector may attribute such a 'policy' with the behavior of the financial sector itself, and view the state as a passive or reactive factor. This may determine how central or relatively minor/inconsequential policies like fractional reserve banking and the central bank's efforts to raise or lower short-term interest rates are to one's view on the creation, inflation and ultimate implosion of an economic bubble. Explanations focusing on interest rates tend to take on a common form, however: When interest rates are set excessively low, (regardless of the mechanism by which it is accomplished) investors tend to avoid putting their capital into savings accounts. Instead, investors tend to leverage their capital by borrowing from banks and invest the leveraged capital in financial assets such as stocks and real estate. Risky leveraged behavior like speculation and Ponzi schemes can lead to an increasingly fragile economy, and may also be part of what pushes asset prices artificially upward until the bubble pops.

Simply put, economic bubbles often occur when too much money is chasing too few assets, causing both good assets and bad assets to appreciate excessively beyond their fundamentals to an unsustainable level. Once the bubble bursts, the fall in prices causes the collapse of unsustainable investment schemes (especially speculative and/or Ponzi investments, but not exclusively so), which leads to a crisis of consumer (and investor) confidence that may result in a financial panic and/or financial crisis; if there is monetary authority like a central bank, it may be forced to take a number of measures in order to soak up the liquidity in the financial system or risk a collapse of its currency. This may involve actions like bailouts of the financial system, but also others that reverse the trend of monetary accommodation, commonly termed forms of 'contractionary monetary policy'.

Some of these measures may include raising interest rates, which tends to make investors become more risk averse and thus avoid leveraged capital because the costs of borrowing may become too expensive. Others may be countermeasures taken pre-emptively during periods of strong economic growth, such as increasing capital reserve requirements and implementing regulation that checks and/or prevents processes leading to over-expansion and excessive leveraging of debt. Ideally, such countermeasures lessen the impact of a downturn by strengthening financial institutions while the economy is strong.

Advocates of perspectives stressing the role of credit money in an economy often refer to (such) bubbles as "credit bubbles", and look at such measures of financial leverage as debt-to-GDP ratios to identify bubbles. Typically the collapse of any economic bubble results in an economic contraction termed (if less severe) a recession or (if more severe) a depression; what economic policies to follow in reaction to such a contraction is a hotly debated perennial topic of political economy.

The importance of liquidity was derived in a mathematical setting and in an experimental setting.

Social psychology factors

Greater fool theory

Greater fool theory states that bubbles are driven by the behavior of perennially optimistic market participants (the fools) who buy overvalued assets in anticipation of selling it to other speculators (the greater fools) at a much higher price. According to this explanation, the bubbles continue as long as the fools can find greater fools to pay up for the overvalued asset. The bubbles will end only when the greater fool becomes the greatest fool who pays the top price for the overvalued asset and can no longer find another buyer to pay for it at a higher price. This theory is popular among laity but has not yet been fully confirmed by empirical research.

Extrapolation

Extrapolation is projecting historical data into the future on the same basis; if prices have risen at a certain rate in the past, they will continue to rise at that rate forever. The argument is that investors tend to extrapolate past extraordinary returns on investment of certain assets into the future, causing them to overbid those risky assets in order to attempt to continue to capture those same rates of return.

Overbidding on certain assets will at some point result in uneconomic rates of return for investors; only then the asset price deflation will begin. When investors feel that they are no longer well compensated for holding those risky assets, they will start to demand higher rates of return on their investments.

Herding

Another related explanation used in behavioral finance lies in herd behavior, the fact that investors tend to buy or sell in the direction of the market trend. This is sometimes helped by technical analysis that tries precisely to detect those trends and follow them, which creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Investment managers, such as stock mutual fund managers, are compensated and retained in part due to their performance relative to peers. Taking a conservative or contrarian position as a bubble builds results in performance unfavorable to peers. This may cause customers to go elsewhere and can affect the investment manager's own employment or compensation. The typical short-term focus of U.S. equity markets exacerbates the risk for investment managers that do not participate during the building phase of a bubble, particularly one that builds over a longer period of time. In attempting to maximize returns for clients and maintain their employment, they may rationally participate in a bubble they believe to be forming, as the risks of not doing so outweigh the benefits.

Moral hazard

Moral hazard is the prospect that a party insulated from risk may behave differently from the way it would behave if it were fully exposed to the risk. A person's belief that they are responsible for the consequences of their own actions is an essential aspect of rational behavior. An investor must balance the possibility of making a return on their investment with the risk of making a loss – the risk-return relationship. A moral hazard can occur when this relationship is interfered with, often via government policy.

A recent example is the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), signed into law by U.S. President George W. Bush on 3 October 2008 to provide a Government bailout for many financial and non-financial institutions who speculated in high-risk financial instruments during the housing boom condemned by a 2005 story in The Economist titled "The worldwide rise in house prices is the biggest bubble in history". A historical example was intervention by the Dutch Parliament during the great Tulip Mania of 1637.

Other causes of perceived insulation from risk may derive from a given entity's predominance in a market relative to other players, and not from state intervention or market regulation. A firm – or several large firms acting in concert (see cartel, oligopoly and collusion) – with very large holdings and capital reserves could instigate a market bubble by investing heavily in a given asset, creating a relative scarcity which drives up that asset's price. Because of the signaling power of the large firm or group of colluding firms, the firm's smaller competitors will follow suit, similarly investing in the asset due to its price gains.

However, in relation to the party instigating the bubble, these smaller competitors are insufficiently leveraged to withstand a similarly rapid decline in the asset's price. When the large firm, cartel or de facto collusive body perceives a maximal peak has been reached in the traded asset's price, it can then proceed to rapidly sell or "dump" its holdings of this asset on the market, precipitating a price decline that forces its competitors into insolvency, bankruptcy or foreclosure.

The large firm or cartel – which has intentionally leveraged itself to withstand the price decline it engineered – can then acquire the capital of its failing or devalued competitors at a low price as well as capture a greater market share (e.g., via a merger or acquisition which expands the dominant firm's distribution chain). If the bubble-instigating party is itself a lending institution, it can combine its knowledge of its borrowers’ leveraging positions with publicly available information on their stock holdings, and strategically shield or expose them to default.

Other possible causes

Some regard bubbles as related to inflation and thus believe that the causes of inflation are also the causes of bubbles. Others take the view that there is a "fundamental value" to an asset, and that bubbles represent a rise over that fundamental value, which must eventually return to that fundamental value. There are chaotic theories of bubbles which assert that bubbles come from particular "critical" states in the market based on the communication of economic factors. Finally, others regard bubbles as necessary consequences of irrationally valuing assets solely based upon their returns in the recent past without resorting to a rigorous analysis based on their underlying "fundamentals".

Experimental and mathematical economics

Bubbles in financial markets have been studied not only through historical evidence, but also through experiments, mathematical and statistical works. Smith, Suchanek and Williams designed a set of experiments in which an asset that gave a dividend with expected value 24 cents at the end of each of 15 periods (and were subsequently worthless) was traded through a computer network. Classical economics would predict that the asset would start trading near $3.60 (15 times $0.24) and decline by 24 cents each period. They found instead that prices started well below this fundamental value and rose far above the expected return in dividends. The bubble subsequently crashed before the end of the experiment. This laboratory bubble has been repeated hundreds of times in many economics laboratories in the world, with similar results.

The existence of bubbles and crashes in such a simple context was unsettling for the economics community that tried to resolve the paradox on various features of the experiments. To address these issues Porter and Smith and others performed a series of experiments in which short selling, margin trading, professional traders all led to bubbles a fortiori.

Much of the puzzle has been resolved through mathematical modeling and additional experiments. In particular, starting in 1989, Gunduz Caginalp and collaborators modeled the trading with two concepts that are generally missing in classical economics and finance. First, they assumed that supply and demand of an asset depended not only on valuation, but on factors such as the price trend. Second, they assumed that the available cash and asset are finite (as they are in the laboratory). This is contrary to the "infinite arbitrage" that is generally assumed to exist, and to eliminate deviations from fundamental value. Utilizing these assumptions together with differential equations, they predicted the following: (a) The bubble would be larger if there was initial undervaluation. Initially, "value-based" traders would buy the undervalued asset creating an uptrend, which would then attract the "momentum" traders and a bubble would be created. (b) When the initial ratio of cash to asset value in a given experiment was increased, they predicted that the bubble would be larger.

An epistemological difference between most microeconomic modeling and these works is that the latter offer an opportunity to test implications of their theory in a quantitative manner. This opens up the possibility of comparison between experiments and world markets.

These predictions were confirmed in experiments that showed the importance of "excess cash" (also called liquidity, though this term has other meanings), and trend-based investing in creating bubbles. When price collars were used to keep prices low in the initial time periods, the bubble became larger. In experiments in which L= (total cash)/(total initial value of asset) were doubled, the price at the peak of the bubble nearly doubled. This provided valuable evidence for the argument that "cheap money fuels markets."

Caginalp's asset flow differential equations provide a link between the laboratory experiments and world market data. Since the parameters can be calibrated with either market, one can compare the lab data with the world market data.

The asset flow equations stipulate that price trend is a factor in the supply and demand for an asset that is a key ingredient in the formation of a bubble. While many studies of market data have shown a rather minimal trend effect, the work of Caginalp and DeSantis on large scale data adjusts for changes in valuation, thereby illuminating a strong role for trend, and providing the empirical justification for the modeling.

The asset flow equations have been used to study the formation of bubbles from a different standpoint in where it was shown that a stable equilibrium could become unstable with the influx of additional cash or the change to a shorter time scale on the part of the momentum investors. Thus a stable equilibrium could be pushed into an unstable one, leading to a trajectory in price that exhibits a large "excursion" from either the initial stable point or the final stable point. This phenomenon on a short time scale may be the explanation for flash crashes.

Stages of an economic bubble

According to the economist Charles P. Kindleberger, the basic structure of a speculative bubble can be divided into 5 phases:

- Substitution: increase in the value of an asset

- Takeoff: speculative purchases (buy now to sell in the future at a higher price and obtain a profit)

- Exuberance: a state of unsustainable euphoria.

- Critical stage: begin to shorten the buyers, some begin to sell.

- Pop (crash): prices plummet

Identifying asset bubbles

Economic or asset price bubbles are often characterized by one or more of the following:

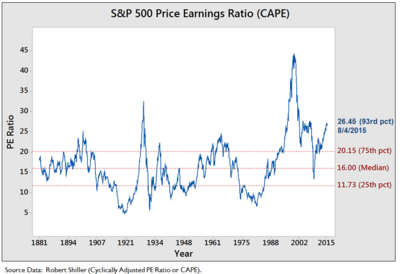

- Unusual changes in single measures, or relationships among measures (e.g., ratios) relative to their historical levels. For example, in the housing bubble of the 2000s, the housing prices were unusually high relative to income. For stocks, the price to earnings ratio provides a measure of stock prices relative to corporate earnings; higher readings indicate investors are paying more for each dollar of earnings.

- Elevated usage of debt (leverage) to purchase assets, such as purchasing stocks on margin or homes with a lower down payment.

- Higher risk lending and borrowing behavior, such as originating loans to borrowers with lower credit quality scores (e.g., subprime borrowers), combined with adjustable rate mortgages and "interest only" loans.

- Rationalizing borrowing, lending and purchase decisions based on expected future price increases rather than the ability of the borrower to repay.

- Rationalizing asset prices by increasingly weaker arguments, such as "this time it's different" or "housing prices only go up."

- A high presence of marketing or media coverage related to the asset.

- Incentives that place the consequences of bad behavior by one economic actor upon another, such as the origination of mortgages to those with limited ability to repay because the mortgage could be sold or securitized, moving the consequences from the originator to the investor.

- International trade (current account) imbalances, resulting in an excess of savings over investments, increasing the volatility of capital flow among countries. For example, the flow of savings from Asia to the U.S. was one of the drivers of the 2000s housing bubble.

- A lower interest rate environment, which encourages lending and borrowing.

Examples of asset bubbles

- Tipper and See-Saw Time (1621)

- Tulip mania (Holland) (1634–1637)

- South Sea Company (British) (1720)

- Mississippi Company (France) (1720)

- Canal Mania (UK) (1790s–1810s)

- Panic of 1819 (US) (1815–1818) Prices of US land in the south and west, cotton (US main export at the time), wheat, corn and tobacco grew into a bubble following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 as the European economy was beginning to recover from wars and demand was high for agricultural goods from America. The Second Bank of the US called in loans for specie beginning in August 1818 popped the speculative land bubble. Prices of agricultural commodities declined by almost -50% during 1819–1821 post bubble. A credit contraction caused by a financial crisis in England drained specie out of the U.S. The Bank of the United States also contracted its lending.

- Panic of 1837 (1834–1837) (US) Prices of US land, cotton, and slaves grew into bubbles with easy bank credit by the mid-1830s. Ended in financial crisis starting with the Specie Circular of 1836. Five year recession followed along with currency in the United States contracting by about 34% with prices falling by 33%. The magnitude of this contraction is only matched by the Great Depression.

- Railway Mania (UK) (1840s)

- Panic of 1857 Land and railroad boom in US following discovery of gold in California in 1849. Resulted in large expansion of US money supply. Railroads boomed as people moved west. Railroad stocks peaks in July 1857. The failure of Ohio Life in August 1857 brought attention to the financial state of the railroad industry and land markets, thereby causing the financial panic to become a more public issue. Since banks had financed the railroads and land purchases, they began to feel the pressures of the falling value of railroad securities and many went bankrupt. Ended in worldwide crisis.

- Melbourne Australia land and real estate bubble (1883–1889, crash in 1890–91)

- Encilhamento ("Mounting") (Brazil) (1886–1892)

- US farm bubble and crisis (1914–1918, crash 1919–1920) prices rapidly escalated during WWI and crash after war's end.

- Roaring Twenties stock-market bubble (US) (1921–1929)

- Florida speculative building bubble (US)(1922–1926)

- Poseidon bubble (Australia) (1969–1970)

- Gold and Silver bubble (1976–1980)

- The dot-com bubble (US) (1995–2000)

- Japanese asset price bubble (1986–1991) Japan real estate and stock market boom

- 1997 Asian financial crisis (1997)

- United States housing bubble (US) (2002–2006)

- China stock and property bubble (China) (2003–2007)

- The 2000s commodity bubbles (2002–2008)

- Uranium bubble of 2007

- Rhodium bubble of 2008 (increase from $500/oz to $9000/oz in July 2008, then down to $1000/oz in January 2009)

- Cryptocurrency bubble (2016–2018)Bitcoin price gain/loss 2011,2013

- 2000s Property bubbles

Other goods which have produced bubbles include: postage stamps and coin collecting.