| Antibiotic | |

|---|---|

Testing the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to antibiotics by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method – antibiotics diffuse from antibiotic-containing disks and inhibit growth of S. aureus, resulting in a zone of inhibition. | |

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of such infections. They may either kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria. A limited number of antibiotics also possess antiprotozoal activity. Antibiotics are not effective against viruses such as the common cold or influenza; drugs which inhibit viruses are termed antiviral drugs or antivirals rather than antibiotics.

Sometimes, the term antibiotic—literally "opposing life", from the Greek roots ἀντι anti, "against" and βίος bios, "life"—is broadly used to refer to any substance used against microbes, but in the usual medical usage, antibiotics (such as penicillin) are those produced naturally (by one microorganism fighting another), whereas nonantibiotic antibacterials (such as sulfonamides and antiseptics) are fully synthetic. However, both classes have the same goal of killing or preventing the growth of microorganisms, and both are included in antimicrobial chemotherapy. "Antibacterials" include antiseptic drugs, antibacterial soaps, and chemical disinfectants, whereas antibiotics are an important class of antibacterials used more specifically in medicine[6] and sometimes in livestock feed.

Antibiotics have been used since ancient times. Many civilizations used topical application of mouldy bread, with many references to its beneficial effects arising from ancient Egypt, Nubia, China, Serbia, Greece, and Rome. The first person to directly document the use of molds to treat infections was John Parkinson (1567–1650). Antibiotics revolutionized medicine in the 20th century. Alexander Fleming (1881–1955) discovered modern day penicillin in 1928, the widespread use of which proved significantly beneficial during wartime. However, the effectiveness and easy access to antibiotics have also led to their overuse and some bacteria have evolved resistance to them. The World Health Organization has classified antimicrobial resistance as a widespread "serious threat [that] is no longer a prediction for the future, it is happening right now in every region of the world and has the potential to affect anyone, of any age, in any country".

Uses, administration and consumption patterns

Medical uses

Antibiotics are used to treat or prevent bacterial infections, and sometimes protozoan infections. (Metronidazole is effective against a number of parasitic diseases). When an infection is suspected of being responsible for an illness but the responsible pathogen has not been identified, an empiric therapy is adopted. This involves the administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic based on the signs and symptoms presented and is initiated pending laboratory results that can take several days.

When the responsible pathogenic microorganism is already known or has been identified, definitive therapy can be started. This will usually involve the use of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic. The choice of antibiotic given will also be based on its cost. Identification is critically important as it can reduce the cost and toxicity of the antibiotic therapy and also reduce the possibility of the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. To avoid surgery, antibiotics may be given for non-complicated acute appendicitis.

Antibiotics may be given as a preventive measure and this is usually limited to at-risk populations such as those with a weakened immune system (particularly in HIV cases to prevent pneumonia), those taking immunosuppressive drugs, cancer patients, and those having surgery. Their use in surgical procedures is to help prevent infection of incisions. They have an important role in dental antibiotic prophylaxis where their use may prevent bacteremia and consequent infective endocarditis. Antibiotics are also used to prevent infection in cases of neutropenia particularly cancer-related.

The use of antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease is not supported by current scientific evidence, and may actually increase cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality and the occurrence of stroke.

Routes of administration

There are many different routes of administration for antibiotic treatment. Antibiotics are usually taken by mouth. In more severe cases, particularly deep-seated systemic infections, antibiotics can be given intravenously or by injection. Where the site of infection is easily accessed, antibiotics may be given topically in the form of eye drops onto the conjunctiva for conjunctivitis or ear drops for ear infections and acute cases of swimmer's ear. Topical use is also one of the treatment options for some skin conditions including acne and cellulitis. Advantages of topical application include achieving high and sustained concentration of antibiotic at the site of infection; reducing the potential for systemic absorption and toxicity, and total volumes of antibiotic required are reduced, thereby also reducing the risk of antibiotic misuse. Topical antibiotics applied over certain types of surgical wounds have been reported to reduce the risk of surgical site infections. However, there are certain general causes for concern with topical administration of antibiotics. Some systemic absorption of the antibiotic may occur; the quantity of antibiotic applied is difficult to accurately dose, and there is also the possibility of local hypersensitivity reactions or contact dermatitis occurring. It is recommended to administer antibiotics as soon as possible, especially in life-threatening infections. Many emergency departments stock antibiotics for this purpose.

Global consumption

Antibiotic consumption varies widely between countries. The WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption’ published in 2018 analysed 2015 data from 65 countries. As measured in defined daily doses per 1,000 inhabitants per day. Mongolia had the highest consumption with a rate of 64.4. Burundi had the lowest at 4.4. Amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid were the most frequently consumed.

Side effects

Antibiotics are screened for any negative effects before their approval for clinical use, and are usually considered safe and well tolerated. However, some antibiotics have been associated with a wide extent of adverse side effects ranging from mild to very severe depending on the type of antibiotic used, the microbes targeted, and the individual patient. Side effects may reflect the pharmacological or toxicological properties of the antibiotic or may involve hypersensitivity or allergic reactions. Adverse effects range from fever and nausea to major allergic reactions, including photodermatitis and anaphylaxis. Safety profiles of newer drugs are often not as well established as for those that have a long history of use.

Common side-effects include diarrhea, resulting from disruption of the species composition in the intestinal flora, resulting, for example, in overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, such as Clostridium difficile. Taking probiotics during the course of antibiotic treatment can help prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Antibacterials can also affect the vaginal flora, and may lead to overgrowth of yeast species of the genus Candida in the vulvo-vaginal area. Additional side effects can result from interaction with other drugs, such as the possibility of tendon damage from the administration of a quinolone antibiotic with a systemic corticosteroid.

Some antibiotics may also damage the mitochondrion, a bacteria-derived organelle found in eukaryotic, including human, cells. Mitochondrial damage cause oxidative stress in cells and has been suggested as a mechanism for side effects from fluoroquinolones. They are also known to affect chloroplasts.

Correlation with obesity

Exposure to antibiotics early in life is associated with increased body mass in humans and mouse models. Early life is a critical period for the establishment of the intestinal microbiota and for metabolic development. Mice exposed to subtherapeutic antibiotic treatment – with either penicillin, vancomycin, or chlortetracycline had altered composition of the gut microbiota as well as its metabolic capabilities. One study has reported that mice given low-dose penicillin (1 μg/g body weight) around birth and throughout the weaning process had an increased body mass and fat mass, accelerated growth, and increased hepatic expression of genes involved in adipogenesis, compared to control mice. In addition, penicillin in combination with a high-fat diet increased fasting insulin levels in mice. However, it is unclear whether or not antibiotics cause obesity in humans. Studies have found a correlation between early exposure of antibiotics (<6 months) and increased body mass (at 10 and 20 months). Another study found that the type of antibiotic exposure was also significant with the highest risk of being overweight in those given macrolides compared to penicillin and cephalosporin. Therefore, there is correlation between antibiotic exposure in early life and obesity in humans, but whether or not there is a causal relationship remains unclear. Although there is a correlation between antibiotic use in early life and obesity, the effect of antibiotics on obesity in humans needs to be weighed against the beneficial effects of clinically indicated treatment with antibiotics in infancy.

Interactions

Birth control pills

There are few well-controlled studies on whether antibiotic use increases the risk of oral contraceptive failure. The majority of studies indicate antibiotics do not interfere with birth control pills, such as clinical studies that suggest the failure rate of contraceptive pills caused by antibiotics is very low (about 1%). Situations that may increase the risk of oral contraceptive failure include non-compliance (missing taking the pill), vomiting, or diarrhea. Gastrointestinal disorders or interpatient variability in oral contraceptive absorption affecting ethinylestradiol serum levels in the blood. Women with menstrual irregularities may be at higher risk of failure and should be advised to use backup contraception during antibiotic treatment and for one week after its completion. If patient-specific risk factors for reduced oral contraceptive efficacy are suspected, backup contraception is recommended.

In cases where antibiotics have been suggested to affect the efficiency of birth control pills, such as for the broad-spectrum antibiotic rifampicin, these cases may be due to an increase in the activities of hepatic liver enzymes' causing increased breakdown of the pill's active ingredients. Effects on the intestinal flora, which might result in reduced absorption of estrogens in the colon, have also been suggested, but such suggestions have been inconclusive and controversial. Clinicians have recommended that extra contraceptive measures be applied during therapies using antibiotics that are suspected to interact with oral contraceptives. More studies on the possible interactions between antibiotics and birth control pills (oral contraceptives) are required as well as careful assessment of patient-specific risk factors for potential oral contractive pill failure prior to dismissing the need for backup contraception.

Alcohol

Interactions between alcohol and certain antibiotics may occur and may cause side effects and decreased effectiveness of antibiotic therapy. While moderate alcohol consumption is unlikely to interfere with many common antibiotics, there are specific types of antibiotics, with which alcohol consumption may cause serious side effects. Therefore, potential risks of side effects and effectiveness depend on the type of antibiotic administered.

Antibiotics such as metronidazole, tinidazole, cephamandole, latamoxef, cefoperazone, cefmenoxime, and furazolidone, cause a disulfiram-like chemical reaction with alcohol by inhibiting its breakdown by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, which may result in vomiting, nausea, and shortness of breath. In addition, the efficacy of doxycycline and erythromycin succinate may be reduced by alcohol consumption. Other effects of alcohol on antibiotic activity include altered activity of the liver enzymes that break down the antibiotic compound.

Pharmacodynamics

The successful outcome of antimicrobial therapy with antibacterial compounds depends on several factors. These include host defense mechanisms, the location of infection, and the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the antibacterial. The bactericidal activity of antibacterials may depend on the bacterial growth phase, and it often requires ongoing metabolic activity and division of bacterial cells. These findings are based on laboratory studies, and in clinical settings have also been shown to eliminate bacterial infection. Since the activity of antibacterials depends frequently on its concentration, in vitro characterization of antibacterial activity commonly includes the determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration of an antibacterial. To predict clinical outcome, the antimicrobial activity of an antibacterial is usually combined with its pharmacokinetic profile, and several pharmacological parameters are used as markers of drug efficacy.

Combination therapy

In important infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, combination therapy (i.e., the concurrent application of two or more antibiotics) has been used to delay or prevent the emergence of resistance. In acute bacterial infections, antibiotics as part of combination therapy are prescribed for their synergistic effects to improve treatment outcome as the combined effect of both antibiotics is better than their individual effect. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections may be treated with a combination therapy of fusidic acid and rifampicin. Antibiotics used in combination may also be antagonistic and the combined effects of the two antibiotics may be less than if one of the antibiotics was given as a monotherapy. For example, chloramphenicol and tetracyclines are antagonists to penicillins. However, this can vary depending on the species of bacteria. In general, combinations of a bacteriostatic antibiotic and bactericidal antibiotic are antagonistic.

In addition to combining one antibiotic with another, antibiotics are sometimes co-administered with resistance-modifying agents. For example, β-lactam antibiotics may be used in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors, such as clavulanic acid or sulbactam, when a patient is infected with a β-lactamase-producing strain of bacteria.

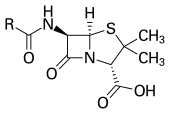

Classes

Antibiotics are commonly classified based on their mechanism of action, chemical structure, or spectrum of activity. Most target bacterial functions or growth processes. Those that target the bacterial cell wall (penicillins and cephalosporins) or the cell membrane (polymyxins), or interfere with essential bacterial enzymes (rifamycins, lipiarmycins, quinolones, and sulfonamides) have bactericidal activities. Protein synthesis inhibitors (macrolides, lincosamides, and tetracyclines) are usually bacteriostatic (with the exception of bactericidal aminoglycosides). Further categorization is based on their target specificity. "Narrow-spectrum" antibiotics target specific types of bacteria, such as gram-negative or gram-positive, whereas broad-spectrum antibiotics affect a wide range of bacteria. Following a 40-year break in discovering classes of antibacterial compounds, four new classes of antibiotics were introduced to clinical use in the late 2000s and early 2010s: cyclic lipopeptides (such as daptomycin), glycylcyclines (such as tigecycline), oxazolidinones (such as linezolid), and lipiarmycins (such as fidaxomicin).

Production

With advances in medicinal chemistry, most modern antibacterials are semisynthetic modifications of various natural compounds. These include, for example, the beta-lactam antibiotics, which include the penicillins (produced by fungi in the genus Penicillium), the cephalosporins, and the carbapenems. Compounds that are still isolated from living organisms are the aminoglycosides, whereas other antibacterials—for example, the sulfonamides, the quinolones, and the oxazolidinones—are produced solely by chemical synthesis. Many antibacterial compounds are relatively small molecules with a molecular weight of less than 1000 daltons.

Since the first pioneering efforts of Howard Florey and Chain in 1939, the importance of antibiotics, including antibacterials, to medicine has led to intense research into producing antibacterials at large scales. Following screening of antibacterials against a wide range of bacteria, production of the active compounds is carried out using fermentation, usually in strongly aerobic conditions.

Resistance

The emergence of resistance of bacteria to antibiotics is a common phenomenon. Emergence of resistance often reflects evolutionary processes that take place during antibiotic therapy. The antibiotic treatment may select for bacterial strains with physiologically or genetically enhanced capacity to survive high doses of antibiotics. Under certain conditions, it may result in preferential growth of resistant bacteria, while growth of susceptible bacteria is inhibited by the drug. For example, antibacterial selection for strains having previously acquired antibacterial-resistance genes was demonstrated in 1943 by the Luria–Delbrück experiment. Antibiotics such as penicillin and erythromycin, which used to have a high efficacy against many bacterial species and strains, have become less effective, due to the increased resistance of many bacterial strains.

Resistance may take the form of biodegradation of pharmaceuticals, such as sulfamethazine-degrading soil bacteria introduced to sulfamethazine through medicated pig feces. The survival of bacteria often results from an inheritable resistance, but the growth of resistance to antibacterials also occurs through horizontal gene transfer. Horizontal transfer is more likely to happen in locations of frequent antibiotic use.

Antibacterial resistance may impose a biological cost, thereby reducing fitness of resistant strains, which can limit the spread of antibacterial-resistant bacteria, for example, in the absence of antibacterial compounds. Additional mutations, however, may compensate for this fitness cost and can aid the survival of these bacteria.

Paleontological data show that both antibiotics and antibiotic resistance are ancient compounds and mechanisms. Useful antibiotic targets are those for which mutations negatively impact bacterial reproduction or viability.

Several molecular mechanisms of antibacterial resistance exist. Intrinsic antibacterial resistance may be part of the genetic makeup of bacterial strains. For example, an antibiotic target may be absent from the bacterial genome. Acquired resistance results from a mutation in the bacterial chromosome or the acquisition of extra-chromosomal DNA. Antibacterial-producing bacteria have evolved resistance mechanisms that have been shown to be similar to, and may have been transferred to, antibacterial-resistant strains. The spread of antibacterial resistance often occurs through vertical transmission of mutations during growth and by genetic recombination of DNA by horizontal genetic exchange. For instance, antibacterial resistance genes can be exchanged between different bacterial strains or species via plasmids that carry these resistance genes. Plasmids that carry several different resistance genes can confer resistance to multiple antibacterials. Cross-resistance to several antibacterials may also occur when a resistance mechanism encoded by a single gene conveys resistance to more than one antibacterial compound.

Antibacterial-resistant strains and species, sometimes referred to as "superbugs", now contribute to the emergence of diseases that were for a while well controlled. For example, emergent bacterial strains causing tuberculosis that are resistant to previously effective antibacterial treatments pose many therapeutic challenges. Every year, nearly half a million new cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) are estimated to occur worldwide. For example, NDM-1 is a newly identified enzyme conveying bacterial resistance to a broad range of beta-lactam antibacterials. The United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency has stated that "most isolates with NDM-1 enzyme are resistant to all standard intravenous antibiotics for treatment of severe infections." On 26 May 2016, an E. coli "superbug" was identified in the United States resistant to colistin, "the last line of defence" antibiotic.

Misuse

Per The ICU Book "The first rule of antibiotics is to try not to use them, and the second rule is try not to use too many of them." Inappropriate antibiotic treatment and overuse of antibiotics have contributed to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Self-prescribing of antibiotics is an example of misuse. Many antibiotics are frequently prescribed to treat symptoms or diseases that do not respond to antibiotics or that are likely to resolve without treatment. Also, incorrect or suboptimal antibiotics are prescribed for certain bacterial infections. The overuse of antibiotics, like penicillin and erythromycin, has been associated with emerging antibiotic resistance since the 1950s. Widespread usage of antibiotics in hospitals has also been associated with increases in bacterial strains and species that no longer respond to treatment with the most common antibiotics.

Common forms of antibiotic misuse include excessive use of prophylactic antibiotics in travelers and failure of medical professionals to prescribe the correct dosage of antibiotics on the basis of the patient's weight and history of prior use. Other forms of misuse include failure to take the entire prescribed course of the antibiotic, incorrect dosage and administration, or failure to rest for sufficient recovery. Inappropriate antibiotic treatment, for example, is their prescription to treat viral infections such as the common cold. One study on respiratory tract infections found "physicians were more likely to prescribe antibiotics to patients who appeared to expect them". Multifactorial interventions aimed at both physicians and patients can reduce inappropriate prescription of antibiotics. The lack of rapid point of care diagnostic tests, particularly in resource-limited settings is considered one of the drivers of antibiotic misuse.

Several organizations concerned with antimicrobial resistance are lobbying to eliminate the unnecessary use of antibiotics. The issues of misuse and overuse of antibiotics have been addressed by the formation of the US Interagency Task Force on Antimicrobial Resistance. This task force aims to actively address antimicrobial resistance, and is coordinated by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institutes of Health, as well as other US agencies. A non-governmental organization campaign group is Keep Antibiotics Working. In France, an "Antibiotics are not automatic" government campaign started in 2002 and led to a marked reduction of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, especially in children.

The emergence of antibiotic resistance has prompted restrictions on their use in the UK in 1970 (Swann report 1969), and the European Union has banned the use of antibiotics as growth-promotional agents since 2003. Moreover, several organizations (including the World Health Organization, the National Academy of Sciences, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration) have advocated restricting the amount of antibiotic use in food animal production. However, commonly there are delays in regulatory and legislative actions to limit the use of antibiotics, attributable partly to resistance against such regulation by industries using or selling antibiotics, and to the time required for research to test causal links between their use and resistance to them. Two federal bills (S.742 and H.R. 2562) aimed at phasing out nontherapeutic use of antibiotics in US food animals were proposed, but have not passed. These bills were endorsed by public health and medical organizations, including the American Holistic Nurses' Association, the American Medical Association, and the American Public Health Association.

Despite pledges by food companies and restaurants to reduce or eliminate meat that comes from animals treated with antibiotics, the purchase of antibiotics for use on farm animals has been increasing every year.

There has been extensive use of antibiotics in animal husbandry. In the United States, the question of emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains due to use of antibiotics in livestock was raised by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1977. In March 2012, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, ruling in an action brought by the Natural Resources Defense Council and others, ordered the FDA to revoke approvals for the use of antibiotics in livestock, which violated FDA regulations.

Studies have shown that common misconceptions about the effectiveness and necessity of antibiotics to treat common mild illnesses contribute to their overuse.

History

Before the early 20th century, treatments for infections were based primarily on medicinal folklore. Mixtures with antimicrobial properties that were used in treatments of infections were described over 2,000 years ago. Many ancient cultures, including the ancient Egyptians and ancient Greeks, used specially selected mold and plant materials to treat infections. Nubian mummies studied in the 1990s were found to contain significant levels of tetracycline. The beer brewed at that time was conjectured to have been the source.

The use of antibiotics in modern medicine began with the discovery of synthetic antibiotics derived from dyes.

Synthetic antibiotics derived from dyes

Synthetic antibiotic chemotherapy as a science and development of antibacterials began in Germany with Paul Ehrlich in the late 1880s. Ehrlich noted certain dyes would color human, animal, or bacterial cells, whereas others did not. He then proposed the idea that it might be possible to create chemicals that would act as a selective drug that would bind to and kill bacteria without harming the human host. After screening hundreds of dyes against various organisms, in 1907, he discovered a medicinally useful drug, the first synthetic antibacterial organoarsenic compound salvarsan, now called arsphenamine.

This heralded the era of antibacterial treatment that was begun with the discovery of a series of arsenic-derived synthetic antibiotics by both Alfred Bertheim and Ehrlich in 1907. Ehrlich and Bertheim had experimented with various chemicals derived from dyes to treat trypanosomiasis in mice and spirochaeta infection in rabbits. While their early compounds were too toxic, Ehrlich and Sahachiro Hata, a Japanese bacteriologist working with Erlich in the quest for a drug to treat syphilis, achieved success with the 606th compound in their series of experiments. In 1910 Ehrlich and Hata announced their discovery, which they called drug "606", at the Congress for Internal Medicine at Wiesbaden. The Hoechst company began to market the compound toward the end of 1910 under the name Salvarsan, now known as arsphenamine. The drug was used to treat syphilis in the first half of the 20th century. In 1908, Ehrlich received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contributions to immunology. Hata was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911 and for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 and 1913.

The first sulfonamide and the first systemically active antibacterial drug, Prontosil, was developed by a research team led by Gerhard Domagk in 1932 or 1933 at the Bayer Laboratories of the IG Farben conglomerate in Germany, for which Domagk received the 1939 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Sulfanilamide, the active drug of Prontosil, was not patentable as it had already been in use in the dye industry for some years. Prontosil had a relatively broad effect against Gram-positive cocci, but not against enterobacteria. Research was stimulated apace by its success. The discovery and development of this sulfonamide drug opened the era of antibacterials.

Penicillin and other natural antibiotics

Observations about the growth of some microorganisms inhibiting the growth of other microorganisms have been reported since the late 19th century. These observations of antibiosis between microorganisms led to the discovery of natural antibacterials. Louis Pasteur observed, "if we could intervene in the antagonism observed between some bacteria, it would offer perhaps the greatest hopes for therapeutics".

In 1874, physician Sir William Roberts noted that cultures of the mold Penicillium glaucum that is used in the making of some types of blue cheese did not display bacterial contamination. In 1876, physicist John Tyndall also contributed to this field.

In 1895 Vincenzo Tiberio, Italian physician, published a paper on the antibacterial power of some extracts of mold.

In 1897, doctoral student Ernest Duchesne submitted a dissertation, "Contribution à l'étude de la concurrence vitale chez les micro-organismes: antagonisme entre les moisissures et les microbes" (Contribution to the study of vital competition in micro-organisms: antagonism between molds and microbes), the first known scholarly work to consider the therapeutic capabilities of molds resulting from their anti-microbial activity. In his thesis, Duchesne proposed that bacteria and molds engage in a perpetual battle for survival. Duchesne observed that E. coli was eliminated by Penicillium glaucum when they were both grown in the same culture. He also observed that when he inoculated laboratory animals with lethal doses of typhoid bacilli together with Penicillium glaucum, the animals did not contract typhoid. Unfortunately Duchesne's army service after getting his degree prevented him from doing any further research. Duchesne died of tuberculosis, a disease now treated by antibiotics.

In 1928, Sir Alexander Fleming postulated the existence of penicillin, a molecule produced by certain molds that kills or stops the growth of certain kinds of bacteria. Fleming was working on a culture of disease-causing bacteria when he noticed the spores of a green mold, Penicillium chrysogenum, in one of his culture plates. He observed that the presence of the mold killed or prevented the growth of the bacteria. Fleming postulated that the mold must secrete an antibacterial substance, which he named penicillin in 1928. Fleming believed that its antibacterial properties could be exploited for chemotherapy. He initially characterized some of its biological properties, and attempted to use a crude preparation to treat some infections, but he was unable to pursue its further development without the aid of trained chemists.

Ernst Chain, Howard Florey and Edward Abraham succeeded in purifying the first penicillin, penicillin G, in 1942, but it did not become widely available outside the Allied military before 1945. Later, Norman Heatley developed the back extraction technique for efficiently purifying penicillin in bulk. The chemical structure of penicillin was first proposed by Abraham in 1942 and then later confirmed by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin in 1945. Purified penicillin displayed potent antibacterial activity against a wide range of bacteria and had low toxicity in humans. Furthermore, its activity was not inhibited by biological constituents such as pus, unlike the synthetic sulfonamides. (see below) The development of penicillin led to renewed interest in the search for antibiotic compounds with similar efficacy and safety. For their successful development of penicillin, which Fleming had accidentally discovered but could not develop himself, as a therapeutic drug, Chain and Florey shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Fleming.

Florey credited René Dubos with pioneering the approach of deliberately and systematically searching for antibacterial compounds, which had led to the discovery of gramicidin and had revived Florey's research in penicillin. In 1939, coinciding with the start of World War II, Dubos had reported the discovery of the first naturally derived antibiotic, tyrothricin, a compound of 20% gramicidin and 80% tyrocidine, from Bacillus brevis. It was one of the first commercially manufactured antibiotics and was very effective in treating wounds and ulcers during World War II. Gramicidin, however, could not be used systemically because of toxicity. Tyrocidine also proved too toxic for systemic usage. Research results obtained during that period were not shared between the Axis and the Allied powers during World War II and limited access during the Cold War.

Late 20th century

During the mid-20th century, the number of new antibiotic substances introduced for medical use increased significantly. From 1935 to 1968, 12 new classes were launched. However, after this, the number of new classes dropped markedly, with only two new classes introduced between 1969 and 2003.

Etymology of the words 'antibiotic' and 'antibacterial'

The term 'antibiosis', meaning "against life", was introduced by the French bacteriologist Jean Paul Vuillemin as a descriptive name of the phenomenon exhibited by these early antibacterial drugs. Antibiosis was first described in 1877 in bacteria when Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch observed that an airborne bacillus could inhibit the growth of Bacillus anthracis. These drugs were later renamed antibiotics by Selman Waksman, an American microbiologist, in 1947.

The term antibiotic was first used in 1942 by Selman Waksman and his collaborators in journal articles to describe any substance produced by a microorganism that is antagonistic to the growth of other microorganisms in high dilution. This definition excluded substances that kill bacteria but that are not produced by microorganisms (such as gastric juices and hydrogen peroxide). It also excluded synthetic antibacterial compounds such as the sulfonamides. In current usage, the term "antibiotic" is applied to any medication that kills bacteria or inhibits their growth, regardless of whether that medication is produced by a microorganism or not.

The term "antibiotic" derives from anti + βιωτικός (biōtikos), "fit for life, lively", which comes from βίωσις (biōsis), "way of life", and that from βίος (bios), "life". The term "antibacterial" derives from Greek ἀντί (anti), "against" + βακτήριον (baktērion), diminutive of βακτηρία (baktēria), "staff, cane", because the first bacteria to be discovered were rod.

Antibiotic pipeline

Both the WHO and the Infectious Disease Society of America report that the weak antibiotic pipeline does not match bacteria's increasing ability to develop resistance. The Infectious Disease Society of America report noted that the number of new antibiotics approved for marketing per year had been declining and identified seven antibiotics against the Gram-negative bacilli currently in phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trials. However, these drugs did not address the entire spectrum of resistance of Gram-negative bacilli. According to the WHO fifty one new therapeutic entities - antibiotics (including combinations), are in phase 1-3 clinical trials as of May 2017. Antibiotics targeting multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens remains a high priority.

A few antibiotics have received marketing authorization in the last seven years. The cephalosporin ceftaroline and the lipoglycopeptides oritavancin and telavancin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. The lipoglycopeptide dalbavancin and the oxazolidinone tedizolid has also been approved for use for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. The first in a new class of narrow spectrum macrocyclic antibiotics, fidaxomicin, has been approved for the treatment of C. difficile colitis. New cephalosporin-lactamase inhibitor combinations also approved include ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-avibactam for complicated urinary tract infection and intra-abdominal infection.

- Ceftolozane/tazobactam (CXA-201; CXA-101/tazobactam): Antipseudomonal cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor combination (cell wall synthesis inhibitor). FDA approved on 19 December 2014.

- Ceftazidime/avibactam (ceftazidime/NXL104): antipseudomonal cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor combination (cell wall synthesis inhibitor). FDA approved on 25 February 2015.

- Ceftaroline/avibactam (CPT-avibactam; ceftaroline/NXL104): Anti-MRSA cephalosporin/ β-lactamase inhibitor combination (cell wall synthesis inhibitor).

- Cefiderocol: cephalosporin siderophore. FDA approved on 14 November 2019.

- Imipenem/relebactam: carbapenem/ β-lactamase inhibitor combination (cell wall synthesis inhibitor). FDA approved on 16 July 2019.

- Meropenem/vaborbactam: carbapenem/ β-lactamase inhibitor combination (cell wall synthesis inhibitor). FDA approved on 29 August 2017.

- Delafloxacin: quinolone (inhibitor of DNA synthesis). FDA approved on 19 June 2017.

- Plazomicin (ACHN-490): semi-synthetic aminoglycoside derivative (protein synthesis inhibitor). FDA approved 25 June 2018.

- Eravacycline (TP-434): synthetic tetracycline derivative (protein synthesis inhibitor targeting bacterial ribosomes). FDA approved on 27 August 2018.

- Omadacycline: semi-synthetic tetracycline derivative (protein synthesis inhibitor targeting bacterial ribosomes). FDA approved on 2 October 2018.

- Lefamulin: pleuromutilin antibiotic. FDA approved on 19 August 2019.

- Brilacidin (PMX-30063): peptide defense protein mimetic (cell membrane disruption). In phase 2.

Possible improvements include clarification of clinical trial regulations by FDA. Furthermore, appropriate economic incentives could persuade pharmaceutical companies to invest in this endeavor. In the US, the Antibiotic Development to Advance Patient Treatment (ADAPT) Act was introduced with the aim of fast tracking the drug development of antibiotics to combat the growing threat of 'superbugs'. Under this Act, FDA can approve antibiotics and antifungals treating life-threatening infections based on smaller clinical trials. The CDC will monitor the use of antibiotics and the emerging resistance, and publish the data. The FDA antibiotics labeling process, 'Susceptibility Test Interpretive Criteria for Microbial Organisms' or 'breakpoints', will provide accurate data to healthcare professionals. According to Allan Coukell, senior director for health programs at The Pew Charitable Trusts, "By allowing drug developers to rely on smaller datasets, and clarifying FDA's authority to tolerate a higher level of uncertainty for these drugs when making a risk/benefit calculation, ADAPT would make the clinical trials more feasible."

Replenishing the antibiotic pipeline and developing other new therapies

Because antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains continue to emerge and spread, there is a constant need to develop new antibacterial treatments. Current strategies include traditional chemistry-based approaches such as natural product-based drug discovery, newer chemistry-based approaches such as drug design traditional biology-based approaches such as immunoglobulin therapy, and experimental biology-based approaches such as phage therapy, fecal microbiota transplants, antisense RNA-based treatments, and CRISPR-Cas9-based treatments.

Natural product-based antibiotic discovery

Most of the antibiotics in current use are natural products or natural product derivatives, and bacterial, fungal, plant and animal extracts are being screened in the search for new antibiotics. Organisms may be selected for testing based on ecological, ethnomedical, genomic or historical rationales. Medicinal plants, for example, are screened on the basis that they are used by traditional healers to prevent or cure infection and may therefore contain antibacterial compounds. Also, soil bacteria are screened on the basis that, historically, they have been a very rich source of antibiotics (with 70 to 80% of antibiotics in current use derived from the actinomycetes).

In addition to screening natural products for direct antibacterial activity, they are sometimes screened for the ability to suppress antibiotic resistance and antibiotic tolerance. For example, some secondary metabolites inhibit drug efflux pumps, thereby increasing the concentration of antibiotic able to reach its cellular target and decreasing bacterial resistance to the antibiotic. Natural products known to inhibit bacterial efflux pumps include the alkaloid lysergol, the carotenoids capsanthin and capsorubin, and the flavonoids rotenone and chrysin. Other natural products, this time primary metabolites rather than secondary metabolites, have been shown to eradicate antibiotic tolerance. For example, glucose, mannitol, and fructose reduce antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, rendering them more susceptible to killing by aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Natural products may be screened for the ability to suppress bacterial virulence factors too. Virulence factors are molecules, cellular structures and regulatory systems that enable bacteria to evade the body's immune defenses (e.g. urease, staphyloxanthin), move towards, attach to, and/or invade human cells (e.g. type IV pili, adhesins, internalins), coordinate the activation of virulence genes (e.g. quorum sensing), and cause disease (e.g. exotoxins). Examples of natural products with antivirulence activity include the flavonoid epigallocatechin gallate (which inhibits listeriolysin O), the quinone tetrangomycin (which inhibits staphyloxanthin), and the sesquiterpene zerumbone (which inhibits Acinetobacter baumannii motility).

Immunoglobulin therapy

Antibodies (anti-tetanus immunoglobulin) have been used in the treatment and prevention of tetanus since the 1910s, and this approach continues to be a useful way of controlling bacterial disease. The monoclonal antibody bezlotoxumab, for example, has been approved by the US FDA and EMA for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, and other monoclonal antibodies are in development (e.g. AR-301 for the adjunctive treatment of S. aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia). Antibody treatments act by binding to and neutralizing bacterial exotoxins and other virulence factors.

Phage therapy

Phage therapy is under investigation as a method of treating antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. Phage therapy involves infecting bacterial pathogens with viruses. Bacteriophages and their host ranges are extremely specific for certain bacteria, thus, unlike antibiotics, they do not disturb the host organism's intestinal microbiota. Bacteriophages, also known simply as phages, infect and kill bacteria primarily during lytic cycles. Phages insert their DNA into the bacterium, where it is transcribed and used to make new phages, after which the cell will lyse, releasing new phage that are able to infect and destroy further bacteria of the same strain. The high specificity of phage protects "good" bacteria from destruction.

Some disadvantages to the use of bacteriophages also exist, however. Bacteriophages may harbour virulence factors or toxic genes in their genomes and, prior to use, it may be prudent to identify genes with similarity to known virulence factors or toxins by genomic sequencing. In addition, the oral and IV administration of phages for the eradication of bacterial infections poses a much higher safety risk than topical application. Also, there is the additional concern of uncertain immune responses to these large antigenic cocktails.

There are considerable regulatory hurdles that must be cleared for such therapies. Despite numerous challenges, the use of bacteriophages as a replacement for antimicrobial agents against MDR pathogens that no longer respond to conventional antibiotics, remains an attractive option.

Fecal microbiota transplants

Fecal microbiota transplants involve transferring the full intestinal microbiota from a healthy human donor (in the form of stool) to patients with C. difficile infection. Although this procedure has not been officially approved by the US FDA, its use is permitted under some conditions in patients with antibiotic-resistant C. difficile infection. Cure rates are around 90%, and work is underway to develop stool banks, standardized products, and methods of oral delivery.

Antisense RNA-based treatments

Antisense RNA-based treatment (also known as gene silencing therapy) involves (a) identifying bacterial genes that encode essential proteins (e.g. the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes acpP, lpxC, and rpsJ), (b) synthesizing single stranded RNA that is complementary to the mRNA encoding these essential proteins, and (c) delivering the single stranded RNA to the infection site using cell-penetrating peptides or liposomes. The antisense RNA then hybridizes with the bacterial mRNA and blocks its translation into the essential protein. Antisense RNA-based treatment has been shown to be effective in in vivo models of P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

In addition to silencing essential bacterial genes, antisense RNA can be used to silence bacterial genes responsible for antibiotic resistance. For example, antisense RNA has been developed that silences the S. aureus mecA gene (the gene that encodes modified penicillin-binding protein 2a and renders S. aureus strains methicillin-resistant). Antisense RNA targeting mecA mRNA has been shown to restore the susceptibility of methicillin-resistant staphylococci to oxacillin in both in vitro and in vivo studies.

CRISPR-Cas9-based treatments

In the early 2000s, a system was discovered that enables bacteria to defend themselves against invading viruses. The system, known as CRISPR-Cas9, consists of (a) an enzyme that destroys DNA (the nuclease Cas9) and (b) the DNA sequences of previously encountered viral invaders (CRISPR). These viral DNA sequences enable the nuclease to target foreign (viral) rather than self (bacterial) DNA.

Although the function of CRISPR-Cas9 in nature is to protect bacteria, the DNA sequences in the CRISPR component of the system can be modified so that the Cas9 nuclease targets bacterial resistance genes or bacterial virulence genes instead of viral genes. The modified CRISPR-Cas9 system can then be administered to bacterial pathogens using plasmids or bacteriophages. This approach has successfully been used to silence antibiotic resistance and reduce the virulence of enterohemorrhagic E. coli in an in vivo model of infection.

Reducing the selection pressure for antibiotic resistance

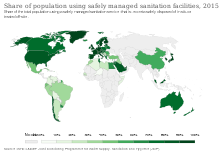

In addition to developing new antibacterial treatments, it is important to reduce the selection pressure for the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance. Strategies to accomplish this include well-established infection control measures such as infrastructure improvement (e.g. less crowded housing), better sanitation (e.g. safe drinking water and food) and vaccine development, other approaches such as antibiotic stewardship, and experimental approaches such as the use of prebiotics and probiotics to prevent infection.

Vaccines

Vaccines rely on immune modulation or augmentation. Vaccination either excites or reinforces the immune competence of a host to ward off infection, leading to the activation of macrophages, the production of antibodies, inflammation, and other classic immune reactions. Antibacterial vaccines have been responsible for a drastic reduction in global bacterial diseases. Vaccines made from attenuated whole cells or lysates have been replaced largely by less reactogenic, cell-free vaccines consisting of purified components, including capsular polysaccharides and their conjugates, to protein carriers, as well as inactivated toxins (toxoids) and proteins.