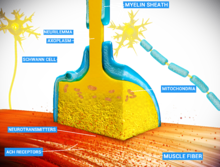

Curare (/kʊˈrɑːri/ or /kjʊˈrɑːri/; koo-rah-ree or kyoo-rah-ree) is a common name for various plant extract alkaloid arrow poisons originating from indigenous peoples in Central and South America. Used as a paralyzing agent for hunting and for therapeutic purposes, Curare only becomes active by a direct wound contamination by a poison dart or arrow or via injection. These poisons function by competitively and reversibly inhibiting the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), which is a subtype of acetylcholine receptor found at the neuromuscular junction. This causes weakness of the skeletal muscles and, when administered in a sufficient dose, eventual death by asphyxiation due to paralysis of the diaphragm. Curare is prepared by boiling the bark of one of the dozens of plant alkaloid sources, leaving a dark, heavy paste that can be applied to arrow or dart heads. Historically, curare has been used as an effective treatment for tetanus or strychnine poisoning and as a paralyzing agent for surgical procedures.

History

The word 'curare' is derived from wurari, from the Carib language of the Macusi of Guyana. It has its origins in the Carib phrase "mawa cure" meaning of the Mawa vine, scientifically known as Strychnos toxifera. Curare is also known among indigenous peoples as Ampi, Woorari, Woorara, Woorali, Wourali, Wouralia, Ourare, Ourari, Urare, Urari, and Uirary.

Classification

Initially, pharmacologist Rudolf Boehm's 1895 sought to classify the various alkaloid poisons based on the containers used for their preparation. During this investigation, he believed curare could be categorized into three main types as seen below . However useful it appeared, it became rapidly outmoded. Richard Gill, a plant collector, found that the indigenous peoples began to use a variety of containers for their curare preparations, henceforth invalidating Boehm's basis of classification.

- Tube or bamboo curare: Mainly composed of the toxin D-tubocurarine, this poison is found packed into hollow bamboo tubes derived from Chondrodendron and other genera in the Menispermaceae. According to their LD50 values, tube curare is thought to be the most toxic.

- Pot curare: Mainly composed of alkaloid components protocurarine (the active ingredient), protocurine (a weak toxicitiy), and protocuridine (non-toxic) from both Menispermaceae and Loganiaceae/Strychnaceae. This subtype is found originally packed in terra cotta pots.

- calabash or gourd curare: Mainly composed of C toxiferine I, this poison is originally packed into hollow gourds from Loganiaceae/Strychnaceae alone.

Manske also observed in his 1955 The Alkaloids:

The results of the early [pre-1900] work were very inaccurate because of the complexity and variation of the composition of the mixtures of alkaloids involved ... these were impure, non-crystalline alkaloids ... Almost all curare preparations were and are complex mixtures, and many of the physiological actions attributed to the early curarizing preparations were undoubtedly due to impurities, particularly to other alkaloids present. The curare preparations are now considered to be of two main types, those from Chondrodendron or other members of the Menispermaceae family and those from Strychnos, a genus of the Loganiaceae [ now Strychnaceae ] family. Some preparations may contain alkaloids from both ... and the majority have other secondary ingredients.

Hunting uses

Curare was used as a paralyzing poison by many South American indigenous people. Since it was too expensive to be used in warfare, curare was mainly used during hunting. The prey was shot by arrows or blowgun darts dipped in curare, leading to asphyxiation owing to the inability of the victim's respiratory muscles to contract. In particular, the poison was used by the Island Caribs, indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean, on the tips of their arrows. In addition, the Yagua people, indigenous to Colombia and northeastern Peru, commonly used these toxins in their blowpipes to target prey 30 to 40 paces distant.

Due to its popularity among the indigenous people as means of paralyzing prey, certain tribes would create monopolies from curare production. Thus, curare became a symbol of wealth among the indigenous populations.

In 1596, Sir Walter Raleigh mentioned the arrow poison in his book Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana (which relates to his travels in Trinidad and Guayana), though the poison he described possibly was not curare. In 1780, Abbe Felix Fontana discovered that it acted on the voluntary muscles rather than the nerves and the heart. In 1832, Alexander von Humboldt gave the first western account of how the toxin was prepared from plants by Orinoco River natives.

During 1811–1812, Sir Benjamin Collins Brody experimented with curare (woorara). He was the first to show that curare does not kill the animal and the recovery is complete if the animal's respiration is maintained artificially. In 1825, Charles Waterton described a classical experiment in which he kept a curarized female donkey alive by artificial respiration with a bellows through a tracheostomy. Waterton is also credited with bringing curare to Europe. Robert Hermann Schomburgk, who was a trained botanist, identified the vine as one of the genus Strychnos and gave it the now accepted name Strychnos toxifera.

Medical use

George Harley (1829–1896) showed in 1850 that curare (wourali) was effective for the treatment of tetanus and strychnine poisoning. In 1857, Claude Bernard (1813–1878) published the results of his experiments in which he demonstrated that the mechanism of action of curare was a result of interference in the conduction of nerve impulses from the motor nerve to the skeletal muscle, and that this interference occurred at the neuromuscular junction. From 1887, the Burroughs Wellcome catalogue listed under its 'Tabloids' brand name, 1⁄12 grain (5.4 mg) tablets of curare (price: 8 shillings) for use in preparing a solution for hypodermic injection. In 1914, Henry Hallett Dale (1875–1968) described the physiological actions of acetylcholine. After 25 years, he showed that acetylcholine is responsible for neuromuscular transmission, which can be blocked by curare.

The best known and historically most important (because of its medical applications) toxin is d-tubocurarine. It was isolated from the crude drug – from a museum sample of curare – in 1935 by Harold King of London, working in Sir Henry Dale's laboratory. King also established its chemical structure. Pascual Scannone, a Venezuelan anesthesiologist who trained and specialized in New York City, did extensive research on curare as a possible paralyzing agent for patients during surgical procedures. In 1942, he became the first person in all of Latin America to use curare during a medical procedure when he successfully performed a tracheal intubation in a patient to whom he administered curare for muscle paralysis at the El Algodonal Hospital in Caracas, Venezuela.

After its introduction in 1942, curare/curare-derivatives became a widely used paralyzing agent during medical and surgical procedures. In medicine, curare has been superseded by a number of curare-like agents, such as pancuronium, which have a similar pharmacodynamic profile, but fewer side effects.

Chemical structure

The various components of curare are organic compounds classified as either isoquinoline or indole alkaloids. Tubocurarine is one of the major active components in the South American dart poison. As an alkaloid, tubocurarine is a naturally occurring compound that consists of nitrogenous bases, although the chemical structure of alkaloids is highly variable.

Like most alkaloids, tubocurarine and C toxiferine consist of a cyclic system with a nitrogen atom in an amine group. On the other hand, while acetylcholine does not contain a cyclic system, it does contain an amine group. Because of this amine group, curare alkaloids can bind readily to the active site of receptors for acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction, blocking nerve impulses from being sent to the skeletal muscles, effectively paralyzing the muscles of the body.

Pharmacological properties

Curare is an example of a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant that blocks the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), one of the two types of acetylcholine (ACh) receptors, at the neuromuscular junction. The main toxin of curare, d-tubocurarine, occupies the same position on the receptor as ACh with an equal or greater affinity, and elicits no response, making it a competitive antagonist. The antidote for curare poisoning is an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor (anti-cholinesterase), such as physostigmine or neostigmine. By blocking ACh degradation, AChE inhibitors raise the amount of ACh in the neuromuscular junction; the accumulated ACh will then correct for the effect of the curare by activating the receptors not blocked by toxin at a higher rate.

The time of onset varies from within one minute (for tubocurarine in intravenous administration, penetrating a larger vein), to between 15 and 25 minutes (for intramuscular administration, where the substance is applied in muscle tissue).

It is harmless if taken orally because curare compounds are too large and highly charged to pass through the lining of the digestive tract to be absorbed into the blood. For this reason, people can safely eat curare-poisoned prey, and it has no effect on its flavor.

Anesthesia

Isolated attempts to use curare during anesthesia date back to 1912 by Arthur Lawen of Leipzig, but curare came to anesthesia via psychiatry (electroplexy). In 1939 Abram Elting Bennett used it to modify metrazol induced convulsive therapy. Muscle relaxants are used in modern anesthesia for many reasons, such as providing optimal operating conditions and facilitating intubation of the trachea. Before muscle relaxants, anesthesiologists needed to use larger doses of the anesthetic agent, such as ether, chloroform or cyclopropane to achieve these aims. Such deep anesthesia risked killing patients who were elderly or had heart conditions.

The source of curare in the Amazon was first researched by Richard Evans Schultes in 1941. Since the 1930s, it was being used in hospitals as a muscle relaxant. He discovered that different types of curare called for as many as 15 ingredients, and in time helped to identify more than 70 species that produced the drug.

In the 1940s, it was used on a few occasions during surgery as it was mistakenly thought to be an analgesic or anesthetic. The patients reported feeling the full intensity of the pain though they were not able to do anything about it since they were essentially paralyzed.

On January 23, 1942, Harold Griffith and Enid Johnson gave a synthetic preparation of curare (Intercostrin/Intocostrin) to a patient undergoing an appendectomy (to supplement conventional anesthesia). Safer curare derivatives, such as rocuronium and pancuronium, have superseded d-tubocurarine for anesthesia during surgery. When used with halothane d-tubocurarine can cause a profound fall in blood pressure in some patients as both the drugs are ganglion blockers. However, it is safer to use d-tubocurarine with ether.

In 1954, an article was published by Beecher and Todd suggesting that the use of muscle relaxants (drugs similar to curare) increased death due to anesthesia nearly sixfold. This was refuted in 1956.

Modern anesthetists have at their disposal a variety of muscle relaxants for use in anesthesia. The ability to produce muscle relaxation irrespective of sedation has permitted anesthetists to adjust the two effects independently and on the fly to ensure that their patients are safely unconscious and sufficiently relaxed to permit surgery. The use of neuromuscular blocking drugs carries with it the risk of anesthesia awareness.

Plant sources

There are dozens of plants from which isoquinoline and indole alkaloids with curarizing effects can be isolated, and which were utilized by indigenous tribes of Central and South America for the production of arrow poisons. Among them are:

In family Menispermaceae:

- Genus Chondrodendron notably C. tomentosum

- Genus Curarea, species C. toxicofera and C. tecunarum

- Genus Sciadotenia toxifera

- Genus Telitoxicum

- Genus Abuta

- Genus Caryomene

- Genus Anomospermum

- Genus Orthomene

- Genus Cissampelos, section L. (Cocculeae) of genus

Other families:

- several species of the genus Strychnos of family Loganiaceae including S. toxifera, S. guianensis, S. castelnaei, S. usambarensis

- a plant in the subfamily Aroideae of family Araceae called taja

- at least three members of the genus Artanthe of family Piperaceae

- Paullinia cururu in the family Sapindaceae

Some plants in the family Aristolochiaceae have also been reported as sources.

Alkaloids with curare-like activity are present in plants of the fabaceous genus Erythrina.

Toxicity

The toxicity of curare alkaloids in humans has not been established. Administration must be parenterally, as gastro-intestinal absorption is ineffective.

LD50 (mg/kg)

human: 0.735 est. (form and method of administration not indicated)

mouse: pot: 0.8–25; tubo: 5-10; calabash: 2–15.

Preparation

In 1807, Alexander von Humboldt provided the first eye-witness account of curare preparation. A mixture of young bark scrapings of the Strychnos plant, other cleaned plant parts, and occasionally snake venom is boiled in water for two days. This liquid is then strained and evaporated to create a dark, heavy, viscid paste that would be tested for its potency later. This curare paste was described to be very bitter in taste.

In 1938, Richard Gill and his expedition collected samples of processed curare and described its method of traditional preparation; one of the plant species used at that time was Chondrodendron tomentosum.

Adjuvants

Various irritating herbs, stinging insects, poisonous worms, and various parts of amphibians and reptiles are added to the preparation. Some of these accelerate the onset of action or increase the toxicity; others prevent the wound from healing or blood from coagulating.

Diagnosis and management of curare poisoning

Curare poisoning can be indicated by typical signs of neuromuscular-blocking drugs such as paralysis including respiration but not directly affecting the heart.

Curare poisoning can be managed by artificial respiration such as mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. In a study of 29 army volunteers that were paralyzed with curare, artificial respiration managed to keep an oxygen saturation of always above 85%, a level at which there is no evidence of altered state of consciousness. Yet, curare poisoning mimics the total locked-in syndrome in that there is paralysis of every voluntarily controlled muscle in the body (including the eyes), making it practically impossible for the victim to confirm consciousness while paralyzed.

Spontaneous breathing is resumed after the end of the duration of action of curare, which is generally between 30 minutes and 8 hours, depending on the variant of the toxin and dosage. Cardiac muscle is not directly affected by curare, but if more than four to six minutes has passed since respiratory cessation the cardiac muscle may stop functioning by oxygen-deprivation, making cardiopulmonary resuscitation including chest compressions necessary.

Chemical antidote

Since tubocurarine and the other components of curare bind reversibly to the ACh receptors, treatment for curare poisoning involves adding an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor, which will stop the destruction of acetylcholine so that it can compete with curare. This can be done by administration of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors such as pyridostigmine, neostigmine, physostigmine, and edrophonium. Acetylcholinesterase is an enzyme used to break down the acetylcholine (ACh) neurotransmitter left over in motor neuron synapses. The aforementioned inhibitors, termed "anticurare" drugs, reversibly bind to the enzyme's active site, prohibiting its ability to bind to its original target, ACh. By blocking ACh degradation, AChE inhibitors can effectively raise the amount of ACh present in the neuromuscular junction. The accumulated ACh will then correct for the effect of the curare by activating the receptors not blocked by toxin at a higher rate, restoring activity to the motor neurons and bodily movement.

Gallery

Abuta selloana. Certain species in the menispermaceous genus Abuta—particularly the Colombian species A. imene—have sometimes been used in the preparation of curare.

Anomospermum schomburgkii. Certain species in the genus Anomospermum have been used in the preparation of some forms of curare.

Cissampelos pareira. Certain species in the genus Cissampelos have been employed in the preparation of curare.