| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Ban Pong, Thailand to Thanbyuzayat, Burma |

| Dates of operation | 1942–1947 (Section to Nam Tok reopened in 1957) |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge |

| Length | 415 km (258 mi) |

The Burma Railway, also known as the Death Railway, the Siam–Burma Railway, the Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, is a 415 km (258 mi) railway between Ban Pong, Thailand and Thanbyuzayat, Burma, built by prisoners of war of the Japanese from 1940–1944 to supply troops and weapons in the Burma campaign of World War II. This railway completed the rail link between Bangkok, Thailand and Rangoon, Burma. The name used by the Japanese Government is Tai–Men Rensetsu Tetsudō (泰緬連接鉄道), which means Thailand-Burma-Link-Railway.

The Thai portion of the railway continues to exist, with three trains crossing the original bridge twice daily bound from Bangkok to the current terminus at Nam Tok. Most of the Burmese portion of the railroad (the spur from the Thai border that connects to the Burma main line to Moulmein) fell into disrepair decades ago and has not seen service since.

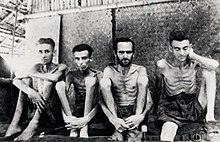

Between 180,000 and 250,000 civilian laborers and over 60,000 Allied prisoners of war were subjected to forced labour during its construction. During the railway's construction, around 90,000 Southeast Asian civilian forced laborers died, along with more than 12,000 Allied prisoners.

History

A railway route between Burma and Thailand, crossing Three Pagodas Pass and following the valley of the Khwae Noi river in Thailand, had been surveyed by the British government of Burma as early as 1885, but the proposed course of the line – through hilly jungle terrain divided by many rivers – was considered too difficult to undertake.

In early 1942, Japanese forces invaded Burma and seized control of the colony from the United Kingdom. To supply their forces in Burma, the Japanese depended upon the sea, bringing supplies and troops to Burma around the Malay peninsula and through the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman Sea. This route was vulnerable to attack by Allied submarines, especially after the Japanese defeat at the Battle of Midway in June 1942. To avoid a hazardous 2,000-mile (3,200 km) sea journey around the Malay peninsula, a railway from Bangkok to Rangoon seemed a feasible alternative. The Japanese began this project in June 1942.

The project aimed to connect Ban Pong in Thailand with Thanbyuzayat in Burma, linking up with existing railways at both places. Its route was through Three Pagodas Pass on the border of Thailand and Burma. 69 miles (111 km) of the railway were in Burma and the remaining 189 miles (304 km) were in Thailand. The movement of POWs northward from Changi Prison in Singapore and other prison camps in Southeast Asia began in May 1942. After preliminary work of airfields and infrastructure, construction of the railway began in Burma on 15 September 1942 and in Thailand in November. The projected completion date was December 1943. Most of the construction materials, including tracks and sleepers, were brought from dismantled branches of Malaya's Federated Malay States Railway network and the East Indies' various rail networks.

The railway was completed ahead of schedule. On 17 October 1943, construction gangs originating in Burma working south met up with construction gangs originating in Thailand working north. The two sections of the line met at kilometre 263, about 18 km (11 mi) south of the Three Pagodas Pass at Konkuita (Kaeng Khoi Tha, Sangkhla Buri District, Kanchanaburi Province).

As an American engineer said after viewing the project, "What makes this an engineering feat is the totality of it, the accumulation of factors. The total length of miles, the total number of bridges — over 600, including six to eight long-span bridges — the total number of people who were involved (one-quarter of a million), the very short time in which they managed to accomplish it, and the extreme conditions they accomplished it under. They had very little transportation to get stuff to and from the workers, they had almost no medication, they couldn’t get food let alone materials, they had no tools to work with except for basic things like spades and hammers, and they worked in extremely difficult conditions — in the jungle with its heat and humidity. All of that makes this railway an extraordinary accomplishment."

The Japanese Army transported 500,000 tonnes of freight over the railway before it fell into Allied hands.

The line was closed in 1947, but the section between Nong Pla Duk and Nam Tok was reopened ten years later in 1957.

On 16 January 1946, the British ordered Japanese POWs to remove a four kilometre stretch of rail between Nikki and Sonkrai. The railway link between Thailand and Burma was to be separated again for protecting British interests in Singapore. After that, the Burma section of the railway was sequentially removed, the rails were gathered in Mawlamyine, and the roadbed was returned to the jungle. The British government sold the railway and related materials to the Thai government for 50 million baht.

Post-war

After the war the railway was in poor condition and needed reconstruction for use by the Royal Thai Railway system. On 24 June 1949, the portion from Kanchanaburi to Nong Pla Duk (Thai หนองปลาดุก) was finished; on the first of April 1952, the next section up to Wang Pho (Wangpo) was done. Finally, on 1 July 1958 the rail line was completed to Nam Tok (Thai น้ำตก, English Sai Yok 'waterfalls'.) The portion in use today is some 130 km (81 mi) long. The line was abandoned beyond Nam Tok Sai Yok Noi; the steel rails were salvaged for reuse in expanding the Bang Sue railway yard, reinforcing the Bangkok–Ban Phachi Junction double track, rehabilitating the track from Thung Song Junction to Trang, and constructing both the Nong Pla Duk–Suphan Buri and Ban Thung Pho–Khiri Rat Nikhom branch lines. Parts of the abandoned route have been converted into a walking trail.

Since the 1990s various proposals have been made to rebuild the complete railway, but as of 2014 these plans had not been realised. Since the upper part of the Khwae valley is now flooded by the Vajiralongkorn Dam, and the surrounding terrain is mountainous, it would take extensive tunneling to reconnect Thailand with Burma by rail.

Labourers

Japanese

Japanese soldiers, 12,000 of them, including 800 Koreans, were employed on the railway as engineers, guards, and supervisors of the POW and rōmusha labourers. Although working conditions were far better for the Japanese than the POWs and rōmusha workers, about 1,000 (eight percent) of them died during construction. Many remember Japanese soldiers as being cruel and indifferent to the fate of Allied prisoners of war and the Asian rōmusha. Many men in the railway workforce bore the brunt of pitiless or uncaring guards. Cruelty could take different forms, from extreme violence and torture to minor acts of physical punishment, humiliation, and neglect.

Civilian labourers

The number of Southeast Asian workers recruited or impressed to work on the Burma railway has been estimated to have been more than 180,000 Southeast Asian civilian labourers (rōmusha). Javanese, Malayan Tamils of Indian origin, Burmese, Chinese, Thai, and other Southeast Asians, forcibly drafted by the Imperial Japanese Army to work on the railway, died in its construction. During the initial stages of the construction of the railway, Burmese and Thais were employed in their respective countries, but Thai workers, in particular, were likely to abscond from the project and the number of Burmese workers recruited was insufficient. The Burmese had welcomed the invasion by Japan and cooperated with Japan in recruiting workers.

In early 1943, the Japanese advertised for workers in Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies, promising good wages, short contracts, and housing for families. When that failed to attract sufficient workers, they resorted to more coercive methods, rounding up workers and impressing them, especially in Malaya. Approximately 90,000 Burmese and 75,000 Malayans worked on the railroad. Other nationalities and ethnic groups working on the railway were Tamils, Chinese, Karen, Javanese, and Singaporean Chinese. Other documents suggest that more than 100,000 Malayan Tamils were brought into the project and around 60,000 perished.

Some workers were attracted by the relatively high wages, but the working conditions for the rōmusha were deadly. British doctor Robert Hardie wrote:

"The conditions in the coolie camps down river are terrible," Basil says, "They are kept isolated from Japanese and British camps. They have no latrines. Special British prisoner parties at Kinsaiyok bury about 20 coolies a day. These coolies have been brought from Malaya under false pretenses – 'easy work, good pay, good houses!' Some have even brought wives and children. Now they find themselves dumped in these charnel houses, driven and brutally knocked about by the Jap and Korean guards, unable to buy extra food, bewildered, sick, frightened. Yet many of them have shown extraordinary kindness to sick British prisoners passing down the river, giving them sugar and helping them into the railway trucks at Tarsao."

Prisoners of war

The first prisoners of war, 3,000 Australians, to go to Burma left Changi Prison in Singapore on 14 May 1942 and journeyed by sea to near Thanbyuzayat (သံဖြူဇရပ် in the Burmese language; in English 'Tin Shelter'), the northern terminus of the railway. They worked on airfields and other infrastructure initially before beginning construction of the railway in October 1942. The first prisoners of war to work in Thailand, 3,000 British soldiers, left Changi by train in June 1942 to Ban Pong, the southern terminus of the railway. More prisoners of war were imported from Singapore and the Dutch East Indies as construction advanced. Construction camps housing at least 1,000 workers each were established every 5–10 miles (8–17 km) of the route. Workers were moved up and down the railway line as needed.

The construction camps consisted of open-sided barracks built of bamboo poles with thatched roofs. The barracks were about 60 m (66 yd) long with sleeping platforms raised above the ground on each side of an earthen floor. Two hundred men were housed in each barracks, giving each man a two-foot wide space in which to live and sleep. Camps were usually named after the kilometre where they were located.

Atrocities

Conditions during construction

The prisoners of war "found themselves at the bottom of a social system that was harsh, punitive, fanatical, and often deadly." The living and working conditions on the Burma Railway were often described as "horrific", with maltreatment, sickness, and starvation. The estimated number of civilian labourers and POWs who died during construction varies considerably, but the Australian Government figures suggest that of the 330,000 people who worked on the line (including 250,000 Asian labourers and 61,000 Allied POWs) about 90,000 of the labourers and about 16,000 Allied prisoners died.

Life in the POW camps was recorded at great risk by artists such as Jack Bridger Chalker, Philip Meninsky, John Mennie, Ashley George Old, and Ronald Searle. Human hair was often used for brushes, plant juices and blood for paint, and toilet paper as the "canvas". Some of their works were used as evidence in the trials of Japanese war criminals. Many are now held by the Australian War Memorial, State Library of Victoria, and the Imperial War Museum in London.

One of the earliest and most respected accounts is ex-POW John Coast's Railroad of Death, first published in 1946 and republished in a new edition in 2014. Coast's work is noted for its detail on the brutality of some Japanese and Korean guards as well as the humanity of others. It also describes the living and working conditions experienced by the POWs, together with the culture of the Thai towns and countryside that became many POWs' homes after leaving Singapore with the working parties sent to the railway. Coast also details the camaraderie, pastimes, and humour of the POWs in the face of adversity.

In his book Last Man Out, H. Robert Charles, an American Marine survivor of the sinking of the USS Houston, writes in depth about a Dutch doctor, Henri Hekking, a fellow POW who probably saved the lives of many who worked on the railway. In the foreword to Charles's book, James D. Hornfischer summarizes: "Dr. Henri Hekking was a tower of psychological and emotional strength, almost shamanic in his power to find and improvise medicines from the wild prison of the jungle". Hekking died in 1994. Charles died in December 2009.

Except for the worst months of the construction period, known as the "Speedo" (mid-spring to mid-October 1943), one of the ways the Allied POWs kept their spirits up was to ask one of the musicians in their midst to play his guitar or accordion, or lead them in a group sing-along, or request their camp comedians to tell some jokes or put on a skit.

After the railway was completed, the POWs still had almost two years to survive before liberation. During this time, most of the POWs were moved to hospital and relocation camps where they could be available for maintenance crews or sent to Japan to alleviate the manpower shortage there. In these camps entertainment flourished as an essential part of their rehabilitation. Theatres of bamboo and attap (palm fronds) were built, sets, lighting, costumes and makeup devised, and an array of entertainment produced that included music halls, variety shows, cabarets, plays, and musical comedies—even pantomimes. These activities engaged numerous POWs as actors, singers, musicians, designers, technicians, and female impersonators.

POWs and Asian workers were also used to build the Kra Isthmus Railway from Chumphon to Kra Buri, and the Sumatra or Palembang Railway from Pekanbaru to Muaro.

The construction of the Burma Railway is counted as a war crime committed by Japan in Asia. Hiroshi Abe, a first lieutenant who supervised construction of the railway at Sonkrai where 1,400 British prisoners out of 1,600 died of cholera and other diseases in three months, was sentenced to death, later commuted to 15 years in prison, as a B/C class war criminal.

After the completion of the railroad, most of the POWs were then transported to Japan. Those left to maintain the line still suffered from appalling living conditions as well as increasing Allied air raids.

Death rates and causes

| Country of origin | POWs | Number of deaths | Death rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK, British India or crown colony | 30,131 | 6,904 | 23% |

| Netherlands or Dutch East Indies |

17,990 | 2,782 | 15% |

| Australia | 13,004 | 2,802 | 22% |

| United States | 686 | 133 | 19% |

| Total | 61,811 | 12,621 | 20% |

In addition to malnutrition and physical abuse, malaria, cholera, dysentery and tropical ulcers were common contributing factors in the death of workers on the Burma Railway.

Estimates of deaths among Southeast Asian civilians subject to forced labour, often known as rōmusha, vary widely. However, authorities agree that the percentage of deaths among the rōmusha was much higher than among the Allied military personnel. The total number of rōmusha working on the railway may have reached 300,000 and according to some estimates, the death rate among them was as high as 50 percent. The labourers that suffered the highest casualties were Javanese and Tamils from Malaysia and Myanmar, as well as many Burmese.

A lower death rate among Dutch POWs and internees, relative to those from the UK and Australia, has been linked to the fact that many personnel and civilians taken prisoner in the Dutch East Indies had been born there, were long-term residents and/or had Eurasian ancestry; they tended thus to be more resistant to tropical diseases and to be better acclimatized than other Western Allied personnel.

The quality of medical care received by different groups of prisoners varied enormously. One factor was that many European and US doctors had little experience with tropical diseases. For example, a group of 400 Dutch prisoners, which included three doctors with extensive tropical medicine experience, suffered no deaths at all. Another group, numbering 190 US personnel, to whom Luitenant Henri Hekking, a Dutch medical officer with experience in the tropics was assigned, suffered only nine deaths. Another cohort of 450 US personnel suffered 100 deaths.

Weight loss among Allied officers who worked on construction was, on average, 9–14 kg (20–30 lb) less than that of enlisted personnel.

Workers in more isolated areas suffered a much higher death rate than did others.

War crimes trials

At the end of World War II, 111 Japanese military officials were tried for war crimes for their brutality during the construction of the railway. Thirty-two of them were sentenced to death. No compensation or reparations have been provided to Southeast Asian victims.

Notable structures

The bridge on the River Kwai

One of the most notable portions of the entire railway line is Bridge 277, the so-called "Bridge on the River Kwai", which was built over a stretch of the river that was then known as part of the Mae Klong River. The greater part of the Thai section of the river's route followed the valley of the Khwae Noi River (khwae, 'stream, river' or 'tributary'; noi, 'small'. Khwae was frequently mispronounced by non-Thai speakers as kwai, or 'buffalo' in Thai). This gave rise to the name of "River Kwai" in English. In 1960, because of discrepancies between facts and fiction, the portion of the Mae Klong which passes under the bridge was renamed the Khwae Yai (แควใหญ่ in the Thai language; in English, 'big tributary').

The bridge was made famous by Pierre Boulle's book and its film adaptation, The Bridge on the River Kwai. However, there are many who point out that both Boulle's story and the film which was adapted from it were unrealistic and do not show how poor the conditions and general treatment of the Japanese-held prisoners of war were. Some Japanese viewers resented the movie's depiction of their engineers' capabilities as inferior and less advanced than they were in reality. Japanese engineers had been surveying and planning the route of the railway since 1937, and they had demonstrated considerable skill during their construction efforts across South-East Asia. Some Japanese viewers also disliked the film for portraying the Allied prisoners of war as more capable of constructing the bridge than the Japanese engineers themselves were, accusing the filmmakers of being unfairly biased and unfamiliar of realities of the bridge construction, a sentiment echoed by surviving prisoners of war who saw the film in cinemas.

A first wooden railroad bridge over the Khwae Yai was finished in February 1943, which was soon accompanied by a more modern ferro-concrete bridge in June 1943, with both bridges running in a NNE–SSW direction across the river. The newer steel and concrete bridge was made up of eleven curved-truss bridge spans which the Japanese builders brought over from Java in the Dutch East Indies in 1942. This is the bridge that still remains today. It was this Bridge 277 that was to be attacked with the help of one of the world's first examples of a precision-guided munition, the US VB-1 AZON MCLOS-guided 1,000 lb aerial ordnance, on 23 January 1945. Bad weather forced the cancellation of the mission and the AZON was never deployed against the bridge.

According to Thai-based Hellfire Tours, the "two bridges were successfully bombed and damaged on 13 February of 1945 by bomber aircraft from the Royal Air Force (RAF). Repairs were carried out by forced labour of POWs shortly after and by April the wooden railroad trestle bridge was back in operation. On 3 April, a second bombing raid, this time by Liberator heavy bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), damaged the wooden railroad bridge once again. Repair work soon commenced afterwards and continued again and both bridges were operational again by the end of May. A second air-raid by the RAF on 24 June finally severely damaged and destroyed the railroad bridges and put the entire railway line out of commission for the rest of the war. After Japan's capitulation, the British Army removed about 3.9 kilometres of the original Japanese railroad track on the Thai–Burma border. A survey of the track had shown that its poor construction would not support commercial railroad traffic. The recovered tracks were subsequently sold to Thai Railways and the 130 km Ban Pong–Nam Tok section of railway was relaid and is still in use up to today." Also, after the war, the two curved spans of the bridge which collapsed from the British air attack were replaced by angular truss spans provided by Japan as part of their postwar reparations, thus forming the iconic bridge now seen today.

The new railway line did not fully connect with the Burmese railroad network as no railroad bridges were built which crossed the river between Moulmein and Martaban (the former on the river's southern bank and the latter to the opposite on the northern bank). Thus, ferries were needed as an alternative connecting system. A bridge was not built until the Thanlwin Bridge (carrying both regular road and railroad traffic) was constructed between 2000 and 2005.

Hellfire Pass

Hellfire Pass in the Tenasserim Hills was a particularly difficult section of the line to build: it was the largest rock cutting on the railway, it was in a remote area and the workers lacked proper construction tools during building. The Australian, British, Dutch and other Allied prisoners of war, along with Chinese, Malay, and Tamil labourers, were required by the Japanese to complete the cutting. Sixty-nine men were beaten to death by Japanese guards in the twelve weeks it took to build the cutting, and many more died from cholera, dysentery, starvation, and exhaustion.

Significant bridges

- 346.4 m (1,136 ft) iron bridge across Kwae Yai River at Tha Makham km. 56 + 255.1

- 90 m (300 ft) wooden trestle across Songkalia River km. 294 + 418

- 56 m (184 ft) wooden trestle across Mekaza River km. 319 + 798

- 75 m (246 ft) wooden trestle across Zamithi River km. 329 + 678

- 50 m (160 ft) concrete bridge across Apalong River km. 333 + 258.20

- 60 m (200 ft) wooden trestle across Anakui River km. 369 + 839.5

Cemeteries and memorials

After the war, the remains of most of the war dead were moved from former POW camps, burial grounds and lone graves along the rail line to official war cemeteries.

Three cemeteries maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) contain the vast majority of Allied military personnel who died on the Burma Railway.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, in the city of Kanchanaburi, contains the graves of 6,982 personnel comprising:

- 3,585 British

- 1,896 Dutch

- 1,362 Australians

- 12 members of the Indian Army (including British officers)

- 2 New Zealanders

- 2 Danes

- 8 Canadians

A memorial at the Kanchanaburi cemetery lists 11 other members of the Indian Army, who are buried in nearby Muslim cemeteries.

Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery, at Thanbyuzayat, 65 kilometres south of Moulmein, Myanmar (Burma) has the graves of 3,617 POWs who died on the Burmese portion of the line.

- Cenotaph for the victims, built by Japanese in Thanbyuzayat, Myanmar

Chungkai War Cemetery, near Kanchanaburi, has a further 1,693 war graves.

- 1,373 British

- 314 Dutch

- 6 Indian Army

The remains of United States personnel were repatriated. Of the 668 US personnel forced to work on the railway, 133 died. This included personnel from USS Houston and the 131st Field Artillery Regiment of the Texas Army National Guard. The Americans were called the Lost Battalion as their fate was unknown to the United States for more than two years after their capture.

Several museums are dedicated to those who perished building the railway. The largest of these is at Hellfire Pass (north of the current terminus at Nam Tok), a cutting where the greatest number of lives were lost. An Australian memorial is at Hellfire Pass. One museum is in Myanmar side Thanbyuzayat, and two other museums are in Kanchanaburi: the Thailand–Burma Railway Centre, opened in March 2003, and the JEATH War Museum. There is a memorial plaque at the Kwai bridge itself and an historic wartime steam locomotive is on display.

A preserved section of line has been rebuilt at the National Memorial Arboretum in England.

Notable labourers

- Sir Harold Atcherley, businessman, public figure and arts administrator in the United Kingdom

- Idris James Barwick, author of In the Shadow of Death, died in 1974

- Theo Bot (1911–1984), Dutch politician and diplomat, government minister and ambassador

- Leo Britt, British theatrical producer in Chungkai, Kachu Mountain, and Nakhon Nai

- Sir John Carrick, Australian senator

- Norman Carter, Australian theatrical producer in Bicycle Camp, Java, in numerous camps on the Burma side of the construction, and later in Tamarkan, Thailand

- Jack Bridger Chalker, artist best known for his work recording the lives of prisoners of war in World War II

- Anthony Chenevix-Trench (1919–1979), headmaster of Eton College, 1964–1970 and Fettes College 1972–1979

- Sir Albert Coates, chief Australian medical officer on the railway

- John Coast (1916–1989), British writer and music promoter. He wrote one of the earliest and most respected POW memoirs, Railroad of Death (1946).

- Col. John Harold Henry Coombes, founder and the first Principal of Cadet College Petaro in Pakistan

- Sir Ernest Edward "Weary" Dunlop, Australian surgeon renowned for his leadership of POWs on the railway

- Ringer Edwards, Australian soldier who survived crucifixion at the hands of Japanese soldiers while working on the line

- Arch Flanagan (1915–2013), Australian soldier and father of novelist Richard Flanagan and Martin Flanagan

- Keith Flanagan (d. 2008) Australian soldier, journalist and campaigner for recognition of Weary Dunlop

- William Frankland, British immunologist whose achievements include the popularisation of the pollen count as a piece of weather-related information to the British public and the prediction of increased levels of allergy to penicillin

- Ernest Gordon, the former Presbyterian dean of the chapel at Princeton University

- R. M. Hare, philosopher

- Wim Kan, Dutch comedian and cabaret producer on the Burma side of the railway during the construction period and later in Nakhon Pathom Hospital Camp in Thailand

- Hamilton Lamb (1900–1943), Australian politician and member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly, died of illness and malnutrition at railway camp 131 Kilo in Thailand

- Eric Lomax, author of The Railway Man, an autobiography based on these events, which has been made into a film of the same name starring Colin Firth and Nicole Kidman

- Jacob Markowitz, Romanian-born Canadian physician (1901–1969), AKA the "Jungle Surgeon", who enlisted with the RAMC

- Tan Sri Professor Sir Alexander Oppenheim, British mathematician, started a POW university for his fellow workers

- Frank Pantridge, British physician

- Donald Purdie (d. 27 May 1943), British chemistry professor and department head at Raffles College, Singapore; Purdie died during construction of the railway

- Rowley Richards, Australian doctor who kept detailed notes of his time as a medical officer on the railway. He later wrote a book detailing his experiences

- Rohan Rivett, Australian war correspondent in Singapore; captured after travelling 700 km, predominantly by rowboat, from Singapore; Rivett spent three years working on the Burma railway and later wrote a book chronicling the events.

- Ronald Searle, British cartoonist, creator of the St Trinian's School characters

- E. W. Swanton (1907–2000), Cricket writer and broadcaster. Mentioned in his autobiography — Sort of a cricket person

- Arie Smit (1916–2016), Dutch artist and colonial army lithographer; captured in East Java by Japanese in March 1942, sent to Changi Prison and worked on Thai section of railway

- Philip Toosey, senior Allied officer at the Bridge on the River Kwai

- Reg Twigg (1913–2013), British author Survivor on the River Kwai: Life on the Burma Railway, Private in the Leicestershire Regiment

- Tom Uren, Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party; Minister for Urban and Regional Development in Whitlam government

- Alistair Urquhart, former Gordon Highlander, born in Aberdeen, Scotland. (8 September 1919 – 7 October 2016), author of the book The Forgotten Highlander in which he recalls how he survived his three years on the railway

- Ian Watt (1917–1999), literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University

- David Neville Ffolkes (1912–1966), film and theatre set and costume designer. He won a Tony award in 1947 for his costumes for the play Henry VIII.