The history of money concerns the development throughout time of systems that provide the functions of money. Such systems can be understood as means of trading wealth indirectly; not directly as with bartering. Money is a mechanism that facilitates this process.

Money may take a physical form as in coins and notes, or may exist as a written or electronic account. It may have intrinsic value (commodity money), be legally exchangeable for something with intrinsic value (representative money), or only have nominal value (fiat money).

Overview

The invention of money took place before the beginning of written history. Consequently, any story of how money first developed is mostly based on conjecture and logical inference.

The significant evidence establishes many things were traded in ancient markets that could be described as a medium of exchange. These included livestock and grain–things directly useful in themselves – but also merely attractive items such as cowrie shells or beads were exchanged for more useful commodities. However, such exchanges would be better described as barter, and the common bartering of a particular commodity (especially when the commodity items are not fungible) does not technically make that commodity "money" or a "commodity money" like the shekel – which was both a coin representing a specific weight of barley, and the weight of that sack of barley.

Due to the complexities of ancient history (ancient civilizations developing at different paces and not keeping accurate records or having their records destroyed), and because the ancient origins of economic systems precede written history, it is impossible to trace the true origin of the invention of money. Further, evidence in the histories supports the idea that money has taken two main forms divided into the broad categories of money of account (debits and credits on ledgers) and money of exchange (tangible media of exchange made from clay, leather, paper, bamboo, metal, etc.).

As "money of account" depends on the ability to record a count, the tally stick was a significant development. The oldest of these dates from the Aurignacian, about 30,000 years ago. The 20,000-year-old Ishango Bone – found near one of the sources of the Nile in the Democratic Republic of Congo – seems to use matched tally marks on the thigh bone of a baboon for correspondence counting. Accounting records – in the monetary system sense of the term accounting – dating back more than 7,000 years have been found in Mesopotamia, and documents from ancient Mesopotamia show lists of expenditures, and goods received and traded and the history of accounting evidences that money of account pre-dates the use of coinage by several thousand years. David Graeber proposes that money as a unit of account was invented when the unquantifiable obligation "I owe you one" transformed into the quantifiable notion of "I owe you one unit of something". In this view, money emerged first as money of account and only later took the form of money of exchange.

Regarding money of exchange, the use of representative money historically pre-dates the invention of coinage as well.[2] In the ancient empires of Egypt, Babylon, India and China, the temples and palaces often had commodity warehouses which made use of clay tokens and other materials which served as evidence of a claim upon a portion of the goods stored in the warehouses. There isn't any concrete evidence these kinds of tokens were used for trade, however, only for administration and accounting.

While not the oldest form of money of exchange, various metals (both common and precious metals) were also used in both barter systems and monetary systems and the historical use of metals provides some of the clearest illustration of how the barter systems gave birth to monetary systems. The Romans' use of bronze, while not among the more ancient examples, is well-documented, and it illustrates this transition clearly. First, the "aes rude" (rough bronze) was used. This was a heavy weight of unmeasured bronze used in what was probably a barter system—the barter-ability of the bronze was related exclusively to its usefulness in metalsmithing and it was bartered with the intent of being turned into tools. The next historical step was bronze in bars that had a 5-pound pre-measured weight (presumably to make barter easier and more fair), called "aes signatum" (signed bronze), which is where debate arises between if this is still the barter system or now a monetary system. Finally, there is a clear break from the use of bronze in barter into its undebatable use as money because of lighter measures of bronze not intended to be used as anything other than coinage for transactions. The aes grave (heavy bronze) (or As) is the start of the use of coins in Rome, but not the oldest known example of metal coinage.

Gold and silver have been the most common forms of money throughout history. In many languages, such as Spanish, French, Hebrew and Italian, the word for silver is still directly related to the word for money. Sometimes other metals were used. For instance, Ancient Sparta minted coins from iron to discourage its citizens from engaging in foreign trade. In the early 17th century Sweden lacked precious metals, and so produced "plate money": large slabs of copper 50 cm or more in length and width, stamped with indications of their value.

Gold coins began to be minted again in Europe in the 13th century. Frederick II is credited with having reintroduced gold coins during the Crusades. During the 14th century Europe changed from use of silver in currency to minting of gold. Vienna made this change in 1328.

Metal-based coins had the advantage of carrying their value within the coins themselves – on the other hand, they induced manipulations, such as the clipping of coins to remove some of the precious metal. A greater problem was the simultaneous co-existence of gold, silver and copper coins in Europe. The exchange rates between the metals varied with supply and demand. For instance the gold guinea coin began to rise against the silver crown in England in the 1670s and 1680s. Consequently, silver was exported from England in exchange for gold imports. The effect was worsened with Asian traders not sharing the European appreciation of gold altogether – gold left Asia and silver left Europe in quantities European observers like Isaac Newton, Master of the Royal Mint observed with unease.

Stability came when national banks guaranteed to change silver money into gold at a fixed rate; it did, however, not come easily. The Bank of England risked a national financial catastrophe in the 1730s when customers demanded their money be changed into gold in a moment of crisis. Eventually London's merchants saved the bank and the nation with financial guarantees.

Another step in the evolution of money was the change from a coin being a unit of weight to being a unit of value. A distinction could be made between its commodity value and its specie value. The difference in these values is seigniorage.

Theories of money

The earliest ideas included Aristotle's "metallist" and Plato's "chartalist" concepts, which Joseph Schumpeter integrated into his own theory of money as forms of classification. Especially, the Austrian economist attempted to develop a catallactic theory of money out of Claim Theory. Schumpeter's theory had several themes but the most important of these involve the notions that money can be analyzed from the viewpoint of social accounting and that it is also firmly connected to the theory of value and price.

There are at least two theories of what money is, and these can influence the interpretation of historical and archeological evidence of early monetary systems. The commodity theory of money (money of exchange) is preferred by those who wish to view money as a natural outgrowth of market activity. Others view the credit theory of money (money of account) as more plausible and may posit a key role for the state in establishing money. The Commodity theory is more widely held and much of this article is written from that point of view. Overall, the different theories of money developed by economists largely focus on functions, use, and management of money.

Other theorists also note that the status of a particular form of money always depends on the status ascribed to it by humans and by society. For instance, gold may be seen as valuable in one society but not in another or that a bank note is merely a piece of paper until it is agreed that it has monetary value.

Money supply

In modern times economists have sought to classify the different types of money supply. The different measures of the money supply have been classified by various central banks, using the prefix "M". The supply classifications often depend on how narrowly a supply is specified, for example the "M"s may range from M0 (narrowest) to M3 (broadest). The classifications depend on the particular policy formulation used:

- M0: In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, M0 includes bank reserves, so M0 is referred to as the monetary base, or narrow money.

- MB: is referred to as the monetary base or total currency. This is the base from which other forms of money (like checking deposits, listed below) are created and is traditionally the most liquid measure of the money supply.

- M1: Bank reserves are not included in M1.

- M2: Represents M1 and "close substitutes" for M1. M2 is a broader classification of money than M1. M2 is a key economic indicator used to forecast inflation.

- M3: M2 plus large and long-term deposits. Since 2006, M3 is no longer published by the U.S. central bank. However, there are still estimates produced by various private institutions.

- MZM: Money with zero maturity. It measures the supply of financial assets redeemable at par on demand. Velocity of MZM is historically a relatively accurate predictor of inflation.

Technologies

Assaying

Assaying is analysis of the chemical composition of metals. The discovery of the touchstone for assaying helped the popularisation of metal-based commodity money and coinage. Any soft metal, such as gold, can be tested for purity on a touchstone. As a result, the use of gold for as commodity money spread from Asia Minor, where it first gained wide usage.

A touchstone allows the amount of gold in a sample of an alloy to been estimated. In turn this allows the alloy's purity to be estimated. This allows coins with a uniform amount of gold to be created. Coins were typically minted by governments and then stamped with an emblem that guaranteed the weight and value of the metal. However, as well as intrinsic value coins had a face value. Sometimes governments would reduce the amount of precious metal in a coin (reducing the intrinsic value) and assert the same face value, this practice is known as debasement.

Prehistory: predecessors of money and its emergence

Non-monetary exchange

Gifting and debt

There is no evidence, historical or contemporary, of a society in which barter is the main mode of exchange; instead, non-monetary societies operated largely along the principles of gift economy and debt. When barter did in fact occur, it was usually between either complete strangers or potential enemies.

Barter

With barter, an individual possessing any surplus of value, such as a measure of grain or a quantity of livestock, could directly exchange it for something perceived to have similar or greater value or utility, such as a clay pot or a tool, however, the capacity to carry out barter transactions is limited in that it depends on a coincidence of wants. For example, a farmer has to find someone who not only wants the grain he produced but who could also offer something in return that the farmer wants.

Hypothesis of barter as the origin of money

In Politics Book 1:9 (c. 350 BC) the Greek philosopher Aristotle contemplated the nature of money. He considered that every object has two uses: the original purpose for which the object was designed, and as an item to sell or barter. The assignment of monetary value to an otherwise insignificant object such as a coin or promissory note arises as people acquired a psychological capacity to place trust in each other and in external authority within barter exchange. Finding people to barter with is a time-consuming process; Austrian economist Carl Menger hypothesised that this reason was a driving force in the creation of monetary systems – people seeking a way to stop wasting their time looking for someone to barter with.

In his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, anthropologist David Graeber argues against the suggestion that money was invented to replace barter. The problem with this version of history, he suggests, is the lack of any supporting evidence. His research indicates that gift economies were common, at least at the beginnings of the first agrarian societies, when humans used elaborate credit systems. Graeber proposes that money as a unit of account was invented the moment when the unquantifiable obligation "I owe you one" transformed into the quantifiable notion of "I owe you one unit of something". In this view, money emerged first as credit and only later acquired the functions of a medium of exchange and a store of value. Graeber's criticism partly relies on and follows that made by A. Mitchell Innes in his 1913 article "What is money?". Innes refutes the barter theory of money, by examining historic evidence and showing that early coins never were of consistent value nor of more or less consistent metal content. Therefore, he concludes that sales is not exchange of goods for some universal commodity, but an exchange for credit. He argues that "credit and credit alone is money". Anthropologist Caroline Humphrey examines the available ethnographic data and concludes that "No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing".

Economists Robert P. Murphy and George Selgin replied to Graeber saying that the barter hypothesis is consistent with economic principles, and a barter system would be too brief to leave a permanent record. John Alexander Smith from Bella Caledonia said that in this exchange Graeber is the one acting as a scientist by trying to falsify the barter hypotheses, while Selgin is taking a theological stance by taking the hypothesis as truth revealed from authority.

Gift economy

In a gift economy, valuable goods and services are regularly given without any explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e. there is no formal quid pro quo). Ideally, simultaneous or recurring giving serves to circulate and redistribute valuables within the community.

There are various social theories concerning gift economies. Some consider the gifts to be a form of reciprocal altruism, where relationships are created through this type of exchange. Another interpretation is that implicit "I owe you" debt and social status are awarded in return for the "gifts". Consider for example, the sharing of food in some hunter-gatherer societies, where food-sharing is a safeguard against the failure of any individual's daily foraging. This custom may reflect altruism, it may be a form of informal insurance, or may bring with it social status or other benefits.

Emergence of money

Anthropologists have noted many cases of 'primitive' societies using what looks to us very like money but for non-commercial purposes, indeed commercial use may have been prohibited:

Often, such currencies are never used to buy and sell anything at all. Instead, they are used to create, maintain, and otherwise reorganize relations between people: to arrange marriages, establish the paternity of children, head off feuds, console mourners at funerals, seek forgiveness in the case of crimes, negotiate treaties, acquire followers—almost anything but trade in yams, shovels, pigs, or jewelry.

This suggests that the basic idea of money may have long preceded its application to commercial trade.

After the domestication of cattle and the start of cultivation of crops in 9000–6000 BC, livestock and plant products were used as money. However, it is in the nature of agricultural production that things take time to reach fruition. The farmer may need to buy things that he cannot pay for immediately. Thus the idea of debt and credit was introduced, and a need to record and track it arose.

The establishment of the first cities in Mesopotamia (c. 3000 BCE) provided the infrastructure for the next simplest form of money of account—asset-backed credit or Representative money. Farmers would deposit their grain in the temple which recorded the deposit on clay tablets and gave the farmer a receipt in the form of a clay token which they could then use to pay fees or other debts to the temple. Since the bulk of the deposits in the temple were of the main staple, barley, a fixed quantity of barley came to be used as a unit of account.

Aristotle's opinion of the creation of money of exchange as a new thing in society is:

When the inhabitants of one country became more dependent on those of another, and they imported what they needed, and exported what they had too much of, money necessarily came into use.

Trading with foreigners required a form of money which was not tied to the local temple or economy, money that carried its value with it. A third, proxy, commodity that would mediate exchanges which could not be settled with direct barter was the solution. Which commodity would be used was a matter of agreement between the two parties, but as trade links expanded and the number of parties involved increased the number of acceptable proxies would have decreased. Ultimately, one or two commodities were converged on in each trading zone, the most common being gold and silver.

This process was independent of the local monetary system so in some cases societies may have used money of exchange before developing a local money of account. In societies where foreign trade was rare money of exchange may have appeared much later than money of account.

In early Mesopotamia copper was used in trade for a while but was soon superseded by silver. The temple (which financed and controlled most foreign trade) fixed exchange rates between barley and silver, and other important commodities, which enabled payment using any of them. It also enabled the extensive use of accounting in managing the whole economy, which led to the development of writing and thus the beginning of history.

Bronze Age: commodity money, credit and debt

Many cultures around the world developed the use of commodity money, that is, objects that have value in themselves as well as value in their use as money. Ancient China, Africa, and India used cowry shells.

The Mesopotamian civilization developed a large-scale economy based on commodity money. The shekel was the unit of weight and currency, first recorded c. 3000 BC, which was nominally equivalent to a specific weight of barley that was the preexisting and parallel form of currency. The Babylonians and their neighboring city states later developed the earliest system of economics as we think of it today, in terms of rules on debt, legal contracts and law codes relating to business practices and private property. Money emerged when the increasing complexity of transactions made it useful.

The Code of Hammurabi, the best-preserved ancient law code, was created c. 1760 BC (middle chronology) in ancient Babylon. It was enacted by the sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi. Earlier collections of laws include the code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BC), the Code of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BC) and the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BC). These law codes formalized the role of money in civil society. They set amounts of interest on debt, fines for "wrongdoing", and compensation in money for various infractions of formalized law.

It has long been assumed that metals, where available, were favored for use as proto-money over such commodities as cattle, cowry shells, or salt, because metals are at once durable, portable, and easily divisible. The use of gold as proto-money has been traced back to the fourth millennium BC when the Egyptians used gold bars of a set weight as a medium of exchange, as had been done earlier in Mesopotamia with silver bars.

The first mention in the Bible of the use of money is in the Book of Genesis in reference to criteria for the circumcision of a bought slave. Later, the Cave of Machpelah is purchased (with silver) by Abraham, some time after 1985 BC, although scholars believe the book was edited in the 6th or 5th centuries BC.

1000 BC – 400 AD

First coins

From about 1000 BC, money in the form of small knives and spades made of bronze was in use in China during the Zhou dynasty, with cast bronze replicas of cowrie shells in use before this. The first manufactured actual coins seem to have appeared separately in India, China, and the cities around the Aegean Sea 7th century BC. While these Aegean coins were stamped (heated and hammered with insignia), the Indian coins (from the Ganges river valley) were punched metal disks, and Chinese coins (first developed in the Great Plain) were cast bronze with holes in the center to be strung together. The different forms and metallurgical processes imply a separate development.

All modern coins, in turn, are descended from the coins that appear to have been invented in the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor somewhere around 7th century BC and that spread throughout Greece in the following centuries: disk-shaped, made of gold, silver, bronze or imitations thereof, with both sides bearing an image produced by stamping; one side is often a human head.

Maybe the first ruler in the Mediterranean known to have officially set standards of weight and money was Pheidon. Minting occurred in the late 7th century BC amongst the Greek cities of Asia Minor, spreading to the Greek islands of the Aegean and to the south of Italy by 500 BC. The first stamped money (having the mark of some authority in the form of a picture or words) can be seen in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It is an electrum stater, coined at Aegina island. This coin dates to about 7th century BC.

Herodotus dated the introduction of coins to Italy to the Etruscans of Populonia in about 550 BC.

Other coins made of electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of silver and gold) were manufactured on a larger scale about 7th century BC in Lydia (on the coast of what is now Turkey). Similar coinage was adopted and manufactured to their own standards in nearby cities of Ionia, including Mytilene and Phokaia (using coins of electrum) and Aegina (using silver) during the 7th century BC, and soon became adopted in mainland Greece, and the Persian Empire (after it incorporated Lydia in 547 BC).

The use and export of silver coinage, along with soldiers paid in coins, contributed to the Athenian Empire's dominance of the region in the 5th century BC. The silver used was mined in southern Attica at Laurium and Thorikos by a huge workforce of slave labour. A major silver vein discovery at Laurium in 483 BC led to the huge expansion of the Athenian military fleet.

The worship of Moneta is recorded by Livy with the temple built in the time of Rome 413 (123); a temple consecrated to the same goddess was built in the earlier part of the 4th century (perhaps the same temple). For four centuries the temple contained the mint of Rome. The name of the goddess thus became the source of numerous words in English and the Romance languages, including the words "money" and "mint"

Roman banking system

400–1450

Medieval coins and moneys of account

Charlemagne, in 800 AD, implemented a series of reforms upon becoming "Holy Roman Emperor", including the issuance of a standard coin, the silver penny. Between 794 and 1200 the penny was the only denomination of coin in Western Europe. Minted without oversight by bishops, cities, feudal lords and fiefdoms, by 1160, coins in Venice contained only 0.05g of silver, while England's coins were minted at 1.3g. Large coins were introduced in the mid-13th century. In England, a dozen pennies was called a "shilling" and twenty shillings a "pound".

Debasement of coin was widespread. Significant periods of debasement took place in 1340–60 and 1417–29, when no small coins were minted, and by the 15th century the issuance of small coin was further restricted by government restrictions and even prohibitions. With the exception of the Great Debasement, England's coins were consistently minted from sterling silver (silver content of 92.5%). A lower quality of silver with more copper mixed in, used in Barcelona, was called "billion".

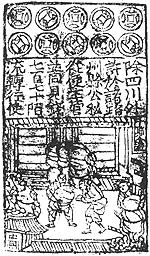

First paper money

Paper money was introduced in Song dynasty China during the 11th century. The development of the banknote began in the seventh century, with local issues of paper currency. Its roots were in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desired to avoid the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions. The issue of credit notes is often for a limited duration, and at some discount to the promised amount later. The jiaozi nevertheless did not replace coins during the Song Dynasty; paper money was used alongside the coins. The central government soon observed the economic advantages of printing paper money, issuing a monopoly right of several of the deposit shops to the issuance of these certificates of deposit. By the early 12th century, the amount of banknotes issued in a single year amounted to an annual rate of 26 million strings of cash coins.

Both the Kabuli rupee and the Kandahari rupee were used as currency in Afghanistan prior to 1891, when they were standardized as the Afghan rupee. The Afghan rupee, which was subdivided into 60 paisas, was replaced by the Afghan afghani in 1925.

Until the middle of the 20th century, Tibet's official currency was also known as the Tibetan rupee.

In the 13th century, paper money became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck. Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his Country." In medieval Italy and Flanders, because of the insecurity and impracticality of transporting large sums of money over long distances, money traders started using promissory notes. In the beginning these were personally registered, but they soon became a written order to pay the amount to whomever had it in their possession. These notes can be seen as a predecessor to regular banknotes.

Trade bills of exchange

Bills of exchange became prevalent with the expansion of European trade toward the end of the Middle Ages. A flourishing Italian wholesale trade in cloth, woolen clothing, wine, tin and other commodities was heavily dependent on credit for its rapid expansion. Goods were supplied to a buyer against a bill of exchange, which constituted the buyer's promise to make payment at some specified future date. Provided that the buyer was reputable or the bill was endorsed by a credible guarantor, the seller could then present the bill to a merchant banker and redeem it in money at a discounted value before it actually became due. The main purpose of these bills nevertheless was, that traveling with cash was particularly dangerous at the time. A deposit could be made with a banker in one town, in turn a bill of exchange was handed out, that could be redeemed in another town.

These bills could also be used as a form of payment by the seller to make additional purchases from his own suppliers. Thus, the bills – an early form of credit – became both a medium of exchange and a medium for storage of value. Like the loans made by the Egyptian grain banks, this trade credit became a significant source for the creation of new money. In England, bills of exchange became an important form of credit and money during last quarter of the 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th century before banknotes, checks and cash credit lines were widely available.

Islamic Golden Age

At around the same time in the medieval Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the 7th–12th centuries on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar). Innovations introduced by Muslim economists, traders and merchants include the earliest uses of credit, cheques, promissory notes, savings accounts, transactional accounts, loaning, trusts, exchange rates, the transfer of credit and debt, and banking institutions for loans and deposits.

Indian subcontinent

In the Indian subcontinent, Sher Shah Suri (1540–1545), introduced a silver coin called a rupiya, weighing 178 grams. Its use was continued by the Mughal Empire. The history of the rupee traces back to Ancient India circa 3rd century BC. Ancient India was one of the earliest issuers of coins in the world, along with the Lydian staters, several other Middle Eastern coinages and the Chinese wen. The term is from rūpya, a Sanskrit term for silver coin, from Sanskrit rūpa, beautiful form.

The imperial taka was officially introduced by the monetary reforms of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the emperor of the Delhi Sultanate, in 1329. It was modeled as representative money, a concept pioneered as paper money by the Mongols in China and Persia. The tanka was minted in copper and brass. Its value was exchanged with gold and silver reserves in the imperial treasury. The currency was introduced due to the shortage of metals.

Tallies

The acceptance of symbolic forms of money meant that a symbol could be used to represent something of value that was available in physical storage somewhere else in space, such as grain in the warehouse; or something of value that would be available later, such as a promissory note or bill of exchange, a document ordering someone to pay a certain sum of money to another on a specific date or when certain conditions have been fulfilled.

In the 12th century, the English monarchy introduced an early version of the bill of exchange in the form of a notched piece of wood known as a tally stick. Tallies originally came into use at a time when paper was rare and costly, but their use persisted until the early 19th century, even after paper money had become prevalent. The notches denoted various amounts of taxes payable to the Crown. Initially tallies were simply a form of receipt to the taxpayer at the time of rendering his dues. As the revenue department became more efficient, they began issuing tallies to denote a promise of the tax assessee to make future tax payments at specified times during the year. Each tally consisted of a matching pair – one stick was given to the assessee at the time of assessment representing the amount of taxes to be paid later, and the other held by the Treasury representing the amount of taxes to be collected at a future date.

The Treasury discovered that these tallies could also be used to create money. When the Crown had exhausted its current resources, it could use the tally receipts representing future tax payments due to the Crown as a form of payment to its own creditors, who in turn could either collect the tax revenue directly from those assessed or use the same tally to pay their own taxes to the government. The tallies could also be sold to other parties in exchange for gold or silver coin at a discount reflecting the length of time remaining until the tax was due for payment. Thus, the tallies became an accepted medium of exchange for some types of transactions and an accepted store of value. Like the girobanks before it, the Treasury soon realized that it could also issue tallies that were not backed by any specific assessment of taxes. By doing so, the Treasury created new money that was backed by public trust and confidence in the monarchy rather than by specific revenue receipts.

1450–1971

Goldsmith bankers

Goldsmiths in England had been craftsmen, bullion merchants, money changers, and money lenders since the 16th century. But they were not the first to act as financial intermediaries; in the early 17th century, the scriveners were the first to keep deposits for the express purpose of relending them. Merchants and traders had amassed huge hoards of gold and entrusted their wealth to the Royal Mint for storage. In 1640 King Charles I seized the private gold stored in the mint as a forced loan (which was to be paid back over time). Thereafter merchants preferred to store their gold with the goldsmiths of London, who possessed private vaults, and charged a fee for that service. In exchange for each deposit of precious metal, the goldsmiths issued receipts certifying the quantity and purity of the metal they held as a bailee (i.e., in trust). These receipts could not be assigned (only the original depositor could collect the stored goods). Gradually the goldsmiths took over the function of the scriveners of relending on behalf of a depositor and also developed modern banking practices; promissory notes were issued for money deposited which by custom and/or law was a loan to the goldsmith, i.e., the depositor expressly allowed the goldsmith to use the money for any purpose including advances to his customers. The goldsmith charged no fee, or even paid interest on these deposits. Since the promissory notes were payable on demand, and the advances (loans) to the goldsmith's customers were repayable over a longer time period, this was an early form of fractional reserve banking. The promissory notes developed into an assignable instrument, which could circulate as a safe and convenient form of money backed by the goldsmith's promise to pay. Hence goldsmiths could advance loans in the form of gold money, or in the form of promissory notes, or in the form of checking accounts. Gold deposits were relatively stable, often remaining with the goldsmith for years on end, so there was little risk of default so long as public trust in the goldsmith's integrity and financial soundness was maintained. Thus, the goldsmiths of London became the forerunners of British banking and prominent creators of new money based on credit.

First European banknotes

The first European banknotes were issued by Stockholms Banco, a predecessor of Sweden's central bank Sveriges Riksbank, in 1661. These replaced the copper-plates being used instead as a means of payment, although in 1664 the bank ran out of coins to redeem notes and ceased operating in the same year.

Inspired by the success of the London goldsmiths, some of whom became the forerunners of great English banks, banks began issuing paper notes quite properly termed "banknotes", which circulated in the same way that government-issued currency circulates today. In England this practice continued up to 1694. Scottish banks continued issuing notes until 1850, and still do issue banknotes backed by Bank of England notes. In the United States, this practice continued through the 19th century; at one time there were more than 5,000 different types of banknotes issued by various commercial banks in America. Only the notes issued by the largest, most creditworthy banks were widely accepted. The scrip of smaller, lesser-known institutions circulated locally. Farther from home it was only accepted at a discounted rate, if at all. The proliferation of types of money went hand in hand with a multiplication in the number of financial institutions.

These banknotes were a form of representative money which could be converted into gold or silver by application at the bank. Since banks issued notes far in excess of the gold and silver they kept on deposit, sudden loss of public confidence in a bank could precipitate mass redemption of banknotes and result in bankruptcy.

In India the earliest paper money was issued by Bank of Hindostan (1770– 1832), General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1773–75), and Bengal Bank (1784–91).

The use of banknotes issued by private commercial banks as legal tender has gradually been replaced by the issuance of bank notes authorized and controlled by national governments. The Bank of England was granted sole rights to issue banknotes in England after 1694. In the United States, the Federal Reserve Bank was granted similar rights after its establishment in 1913. Until recently, these government-authorized currencies were forms of representative money, since they were partially backed by gold or silver and were theoretically convertible into gold or silver.

1971–present

In 1971, United States President Richard Nixon announced that the US dollar would not be directly convertible to Gold anymore. This measure effectively destroyed the Bretton Woods system by removing one of its key components, in what came to be known as the Nixon shock. Since then, the US dollar, and thus all national currencies, are free-floating currencies. Additionally, international, national and local money is now dominated by virtual credit rather than real bullion.

Payment cards

In the late 20th century, payment cards such as credit cards and debit cards became the dominant mode of consumer payment in the First World. The Bankamericard, launched in 1958, became the first third-party credit card to acquire widespread use and be accepted in shops and stores all over the United States, soon followed by the Mastercard and the American Express. Since 1980, Credit Card companies are exempt from state usury laws, and so can charge any interest rate they see fit. Outside America, other payment cards became more popular than credit cards, such as France's Carte Bleue.

Digital currency

The development of computer technology in the second part of the twentieth century allowed money to be represented digitally. By 1990, in the United States, all money transferred between its central bank and commercial banks was in electronic form. By the 2000s most money existed as digital currency in banks databases. In 2012, by number of transaction, 20 to 58 percent of transactions were electronic (dependent on country). The benefit of digital currency is that it allows for easier, faster, and more flexible payments.

Cryptocurrencies

In 2008, Bitcoin was proposed by an unknown author/s under the pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto. It was implemented the same year. Its use of cryptography allowed the currency to have a trustless, fungible and tamper resistant distributed ledger called a blockchain. It became the first widely used decentralized, peer-to-peer, cryptocurrency. Other comparable systems had been proposed since the 1980s. The protocol proposed by Nakamoto solved what is known as the double-spending problem without the need of a trusted third-party.

Since Bitcoin's inception, thousands of other cryptocurrencies have been introduced.