Media bias in the United States occurs when US media outlets skew information, such as reporting news in a way that conflicts with standards of professional journalism or promoting a political agenda through entertainment media. Claims of outlets, writers, and stories exhibiting both have increased as the two-party system has become more polarized, including claims of liberal and conservative bias. There is also bias in reporting to favor the corporate owners, and mainstream bias, a tendency of the media to focus on certain "hot" stories and ignore news of more substance. A variety of watchdog groups attempt to combat bias by fact-checking biased reporting and also unfounded claims of bias. Researchers in a variety of scholarly disciplines study media bias.

Media bias is a vital topic to research as the media plays a large role in informing and swaying citizens on important topics.

History

Before the rise of professional journalism in the early 20th century and the conception of media ethics, newspapers reflected the opinions of the publisher. Frequently, an area would be served by competing newspapers taking differing and often radical views by modern standards. In colonial Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin was an early and forceful advocate for presenting all sides of an issue, writing, for instance, in his "An Apology For Printers" that "... when truth and error have fair play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter." From around 1790 to the late 1800s, most American newspapers were partisan.

In 1798, the Federalist Party in control of Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts designed to weaken the opposition press. It prohibited the publication of "false, scandalous, or malicious writing" against the government and made it a crime to voice any public opposition to any law or presidential act. This part of the law act was in effect until 1801.

President Thomas Jefferson, 1801–1809, was the target of many venomous attacks. He advised editors to divide their newspapers into four sections labeled "truth," "probabilities," "possibilities," and "lies," and observed that the first section would be the smallest and the last the largest. In retirement he grumbled, "Advertisements contain the only truths to be relied on in a newspaper."

In 1861, Federal officials identified newspapers that supported the Confederate cause and ordered many of them closed.

In the 19th century, the accessibility of cheap newspapers allowed the market to expand exponentially. Cities typically had multiple competing newspapers supporting various political factions in each party. To some extent this was mitigated by a separation between news and editorial. News reporting was expected to be relatively neutral or at least factual, whereas editorial sections openly relayed the opinion of the publisher. Editorials often were accompanied by editorial cartoons, which lampooned the publisher's opponents.

Small ethnic newspapers serviced people of various ethnicities, such as Germans, Dutch, Scandinavians, Poles, and Italians. Large cities had numerous foreign-language newspapers, magazines and publishers. They typically were boosters who supported their group's positions on public issues. They disappeared as their readership increasingly became assimilated. In the 1960s and 70s, an effort began to collect these ethnic newspapers in order to preserve their history and increase their accessibility to the general public. In the 20th century, newspapers in various Asian languages, and also in Spanish and Arabic, appeared and are still published, read by newer immigrants.

Starting in the 1890s, a few very high-profile metropolitan newspapers engaged in yellow journalism to increase sales. They emphasized sports, sex, scandal, and sensationalism. The leaders of this style of journalism in New York City were William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. Hearst falsified or exaggerated sensational stories about atrocities in Cuba and the sinking of the USS Maine to boost circulation. Hearst falsely claimed that he had started the war, but in fact the nation's decision makers paid little attention to his shrill demands—President McKinley, for example, did not read the yellow journals.

The Progressive Era, from the 1890s to the 1920s, was reform-oriented. From 1905 to 1915, the muckraker style exposed malefaction in city government and industry. It tended "to exaggerate, misinterpret, and oversimplify events," and got complaints from President Theodore Roosevelt.

The Dearborn Independent, a weekly magazine owned by Henry Ford and distributed free through Ford dealerships, published conspiracy theories about international Jewry in the 1920s. A favorite trope of the anti-Semitism that raged in the 1930s was the allegation that Jews controlled Hollywood and the media. Charles Lindbergh in 1941 claimed American Jews, possessing outsized influence in Hollywood, the media, and the Roosevelt administration, were pushing the nation into war against its interests. Lindbergh received a storm of criticism; the Gallup poll reported that support for his foreign policy views fell to 15%. Hans Thomsen, the senior diplomat at the German Embassy in Washington, reported to Berlin that his efforts to place pro-isolationist articles in American newspapers had failed. "Influential journalists of high repute will not lend themselves, even for money, to publishing such material." Thompson set up a publishing house to produce anti-British books, but almost all of them went unsold. In the years leading up to World War II, The pro-Nazi German American Bund accused the media of being controlled by Jews. They claimed that reports of German mistreatment of Jews were biased and without foundation. They said that Hollywood was a hotbed of Jewish bias, and called for Charlie Chaplin's film The Great Dictator to be banned as an insult to a respected leader.

During the American civil rights movement, conservative newspapers strongly slanted their news about civil rights, blaming the unrest among Southern Blacks on communists. In some cases, Southern television stations refused to air programs such as I Spy and Star Trek because of their racially mixed casts. Newspapers supporting civil rights, labor unions, and aspects of liberal social reform were often accused by conservative newspapers of communist bias.

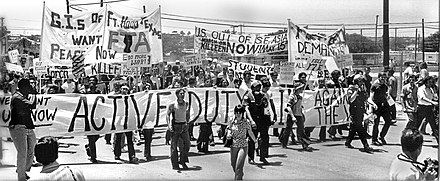

In November 1969, Vice President Spiro Agnew made a landmark speech denouncing what he saw as media bias against the Vietnam War. He called those opposed to the war the "nattering nabobs of negativism."

Starting in the 21st century, social media became a major source of bias, since anyone could post anything without regard to its accuracy. Social media has, on the one hand, allowed all views to be heard, but on the other hand has provided a platform for the most extreme bias.

In 2010, President Obama said that he believed the viewpoints expressed by Fox News was "destructive for the long-term growth" of the United States.

In 2014, the Pew Research Center found that the audience of news was polarized along political alignments.

In late 2015, Donald Trump started his campaign while addressing his concern with the media, calling some information relayed in the media, "fake news." This came shortly after the media began to critique Trump's statements. Information circulated regarding Trump's previous sexual comments made about women.

Beginning around 2016, reports concerning "fake news" became more prominent. It is thought that the use of social media during the Presidential election played a large role in the election of Donald Trump.

There were also many claims made of bias in the media surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic and its politicalization.

Demographic polling

A 1956 American National Election Study found that 66% of Americans thought newspapers were fair, including 78% of Republicans and 64% of Democrats. A 1964 poll by the Roper Organization asked a similar question about network news, and 71% thought network news was fair. A 1972 poll found that 72% of Americans trusted CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite. According to Jonathan M. Ladd's Why Americans Hate the Media and How it Matters, "institutional journalists were [once] powerful guardians of the republic, maintaining high standards of political discourse." Additionally, according to P. Bicak of Partisan Journalism (2018), within the 1988, 1992, and 1996 elections, there were evident paragraphs favoring the Democratic and Republican candidates.

However, Gallup Polls since 1997 have shown that most Americans do not have confidence in the mass media "to report the news fully, accurately, and fairly". According to Gallup, the American public's trust in the media has generally declined in the first decade and a half of the 21st century. Again according to Ladd, in "2008, the portion of Americans expressing 'hardly any' confidence in the press had risen to 45%. A 2004 Chronicle of Higher Education poll found that only 10% of Americans had 'a great deal' of confidence in the 'national news media,'" In 2011, only 44% of those surveyed had "a great deal" or "a fair amount" of trust and confidence in the mass media. In 2013, a 59% majority reported a perception of media bias, with 46% saying mass media was too liberal and 13% saying it was too conservative. The perception of bias was highest among conservatives. According to the poll, 78% of conservatives think the mass media is biased, as compared with 44% of liberals and 50% of moderates. Only about 36% view mass media reporting as "just about right".

A September 2014 Gallup poll found that a plurality of Americans believe the media is "too liberal". According to the poll, 44% of Americans feel that news media are "too liberal" (70% of self-identified conservatives, 35% of self-identified moderates, and 15% of self-identified liberals), 19% believe them to be "too conservative" (12% of self-identified conservatives, 18% of self-identified moderates, and 33% of self-identified liberals), and 34% find it "just about right" (49% of self-identified liberals, 44% of self-identified moderates, and 16% of self-identified conservatives).

In 2016, according to Gottfried and Shearer, "62 percent of US adults get news on social media," with Facebook being the dominant social media site. Again, this seemed to be a major contributor to the presidential election of Donald Trump. According to an article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, "many people who see fake news stories report that they believe them". Trump himself before, during, and after his presidency had and has a highly contentious relationship with the news media, repeatedly referring to them as the "fake news media" and "the enemy of the people," at the same time praising far-right pro-Trump fringe outlets. Trump has regularly lied and promoted conspiracy theories during his presidency.

In 2017, a Gallup poll found that the majority of Americans view the news media favoring a particular political party; 64% believed it favored the Democratic Party, compared to 22% who believed it favored the Republican Party.

In 2017, the trust in media by both Democrats and Republicans changed once again. According to a September 2017 Gallup poll, "Democrats' trust and confidence in the mass media to report the news 'fully, accurately and fairly' has jumped from 51% in 2016 to 72% this year—fueling a rise in Americans' overall confidence to 41%. Independents' trust has risen modestly to 37%, while Republicans' trust is unchanged at 14%."

Shortly before the 2020 election, the Gallup poll showed that confidence in the mass media has continued to decline among Republicans and independent voters, to 10% and 36%, respectively. Among Democratic voters, confidence rose to 73%.

A Gallup poll released in October 2021 showed 68% of Democrats, 31% of independents, and just 11% of Republicans trust the media a great deal or fair amount. Both Democrats' and independents' trust decreased 5% over the past year.

In the 2022 Gallup poll of trust in media, the percentages of confidence per political party vary. For not trust in media, there are 50% of Republicans, 47% of independents, and 10% of Democrats. The trust in media is at its lowest ever recorded. This is the first time ever that the trust percentage is lower than not trusting media outlets.

News values

According to Jonathan M. Ladd, Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters, "The existence of an independent, powerful, widely respected news media establishment is a historical anomaly. Prior to the twentieth century, such an institution had never existed in American history." However, he looks back to the period between 1950 and 1979 as a period where "institutional journalists were powerful guardians of the republic, maintaining high standards of political discourse."

A number of writers have tried to explain the decline in journalistic standards. One explanation is the 24-hour news cycle, which faces the necessity of generating news even when no news-worthy events occur. Another is the simple fact that bad news sells more newspapers than good news. A third possible factor is the market for "news" that reinforces the prejudices of a target audience. In 2014, The New York Times wrote: "In a 2010 paper, Mr. Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, a frequent collaborator and fellow professor at Chicago Booth, found that ideological slants in newspaper coverage typically resulted from what the audience wanted to read in the media they sought out, rather than from the newspaper owners' biases."

As reported by Haselmayer, Wagner, and Meyer in Political Communication, "News value refers to the overall newsworthiness of a message and can be defined by the presence or absence of a number of news factors." The authors contend that media sources shape their coverage in ways that are favorable to them, and are more likely to present messages from outlets their viewers/readers favor. They conclude that majority of what individuals see, read, and hear is pre-determined by the journalists, editors, and reporters of that specific news source.

News outlets face many oppositions from the public and can often be called biased. In some cases, "in order to reach out to a larger audience, a newspaper may forfeit its conservative or liberal position and try to appeal to everyone in the market regardless of their political opinions." Contrary to this type of news outlet, many people look to the news to confirm their beliefs. News outlets can profit more when they can provide news to a certain group of people, allowing them to gain a concrete following, and charge more.

Danny Hayes states that elites create public images for themselves in order to appeal to the values of their potential voters. Large news media corporations can be seen aligning themselves with certain ideologies as well which leads to more bias in the media.

Corporate power

Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, in their book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), proposed a propaganda model thesis to explain systematic biases of United States media as a consequence of the pressure to create a profitable business.

Pro-government

Part of the propaganda model is self-censorship through the corporate system (see corporate censorship); reporters and especially editors share or acquire values that agree with corporate elites to further their careers. Those who do not are marginalized or fired. Such examples have been dramatized in fact-based movie dramas such as Good Night, and Good Luck and The Insider and demonstrated in the documentary The Corporation. George Orwell originally wrote a preface for his 1945 novel Animal Farm, which pointed up the self-censorship during wartime when the Soviet Union was an ally. The preface, first published in 1972, read in part:

- The sinister fact about literary censorship in England is that it is largely voluntary.... Things are] kept right out of the British press, not because the Government intervened but because of a general tacit agreement that 'it wouldn't do' to mention that particular fact.... At this moment what is demanded by the prevailing orthodoxy is an uncritical admiration of Soviet Russia. Everyone knows this, nearly everyone acts on it. Any serious criticism of the Soviet regime, any disclosure of facts which the Soviet Government would prefer to keep hidden, is next door to unprintable." He added, "In our country—it is not the same in all countries: it was not so in Republican France, and it is not so in the United States today—it is the liberals who fear liberty and the intellectuals who want to do dirt on the intellect: it is to draw attention to that fact I have written this preface."

In the propaganda model, advertising revenue is essential for funding most media sources and thus linked with media coverage. For example, according to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), "When Al Gore proposed launching a progressive TV network, a Fox News executive told Advertising Age (October 13, 2003): 'The problem with being associated as liberal is that they wouldn't be going in a direction that advertisers are really interested in.... If you go out and say that you are a liberal network, you are cutting your potential audience, and certainly your potential advertising pool, right off the bat.'" An internal memo from ABC Radio affiliates in 2006 revealed that powerful sponsors had a "standing order that their commercials never be placed on syndicated Air America programming" that aired on ABC affiliates. The list totaled 90 advertisers and included major corporations such as Walmart, General Electric, ExxonMobil, Microsoft, Bank of America, FedEx, Visa, Allstate, McDonald's, Sony, and Johnson & Johnson, as well as government entities such as the United States Postal Service and the United States Navy.

According to Chomsky, US commercial media encourage controversy only within a narrow range of opinion to give the impression of open debate, and they do not report on news that falls outside that range.

Herman and Chomsky argue that comparing the journalistic media product to the voting record of journalists is as flawed a logic as implying auto factory workers design the cars they help produce. They concede that media owners and newsmakers have an agenda but that the agenda is subordinated to corporate interests leaning to the right. It has been argued by some critics, including historian Howard Zinn and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Chris Hedges, that the corporate media routinely ignore the plight of the impoverished while painting a picture of a prosperous America.

In 2008, George W. Bush's press secretary Scott McClellan published a book in which he confessed to regularly and routinely, but unknowingly, passing on misinformation to the media, following the instructions of his superiors. Politicians have willingly misled the press to further their agenda. Scott McClellan characterized the press as, by and large, honest, and intent on telling the truth, but reported that "the national press corps was probably too deferential to the White House", especially on the subject of the war in Iraq.

FAIR reported that between January and August 2014 no representatives for organized labor made an appearance on any of the high-profile Sunday morning talkshows (NBC's Meet the Press, ABC's This Week, Fox News Sunday and CBS's Face the Nation), including episodes that covered topics such as labor rights and jobs, while current or former corporate CEOs made 12 appearances over that same period.

CIA influence

In a 1977 Rolling Stone magazine article, "The CIA and the Media," reporter Carl Bernstein wrote that by 1953, CIA Director Allen Dulles oversaw the media network, which had major influence over 25 newspapers and wire agencies. Its usual modus operandi was to place reports, developed from CIA-provided intelligence, with cooperating or unwitting reporters. Those reports would be repeated or cited by the recipient reporters and would then, in turn, be cited throughout the media wire services. These networks were run by people with well-known liberal but pro-American-big-business and anti-Soviet views, such as William S. Paley (CBS), Henry Luce (Time and Life), Arthur Hays Sulzberger (The New York Times), Alfred Friendly (managing editor of The Washington Post), Jerry O'Leary (The Washington Star), Hal Hendrix (Miami News), Barry Bingham, Sr. (Louisville Courier-Journal), James S. Copley (Copley News Services) and Joseph Harrison (The Christian Science Monitor).

Control

Five corporate conglomerates (Comcast, Disney, Fox Corporation, Paramount Global and Warner Bros. Discovery) own the majority of mass media outlets in the United States. Such a uniformity of ownership means that stories which are critical of these corporations may often be underplayed in the media. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 enabled this handful of corporations to expand their power, and according to Howard Zinn, such mergers "enabled tighter control of information." Chris Hedges argues that corporate media control "of nearly everything we read, watch or hear" is an aspect of what political philosopher Sheldon Wolin calls inverted totalitarianism.

"The guard dog metaphor suggests that media perform as a sentry not for the community as a whole, but for groups having sufficient power and influence to create and control their own security systems." The Guard Dog Theory states that, "the view of media as part of a power oligarchy".

Infotainment

Academics such as McKay, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, and Hudson (see below) have described private U.S. media outlets as profit-driven. For the private media, profits are dependent on viewing figures, regardless of whether the viewers found the programs adequate or outstanding. The strong profit-making incentive of the American media leads them to seek a simplified format and uncontroversial position which will be adequate for the largest possible audience. The market mechanism only rewards media outlets based on the number of viewers who watch those outlets, not by how informed the viewers are, how good the analysis is, or how impressed the viewers are by that analysis.

According to some, the profit-driven quest for high numbers of viewers, rather than high quality for viewers, has resulted in a slide from serious news and analysis to entertainment, sometimes called infotainment:

"Imitating the rhythm of sports reports, exciting live coverage of major political crises and foreign wars was now available for viewers in the safety of their own homes. By the late 1980s, this combination of information and entertainment in news programmes was known as infotainment." [Barbrook, Media Freedom, (London, Pluto Press, 1995) part 14]

Oversimplification

Kathleen Hall Jamieson claimed in her book The Interplay of Influence: News, Advertising, Politics, and the Internet that most television news stories are made to fit into one of five categories:

- Appearance versus reality

- Little guys versus big guys

- Good versus evil

- Efficiency versus inefficiency

- Unique and bizarre events versus ordinary events

Reducing news to the five categories and tending towards an unrealistic black-and-white mentality, simplifies the world into easily understood opposites. According to Jamieson, the media provides an oversimplified skeleton of information that is more easily commercialized.

Media imperialism

Media imperialism is a critical theory regarding the perceived effects of globalization on the world's media, which is often seen as dominated by American media and culture. It is closely tied to the similar theory of cultural imperialism.

- "As multinational media conglomerates grow larger and more powerful many believe that it will become increasingly difficult for small, local media outlets to survive. A new type of imperialism will thus occur, making many nations subsidiary to the media products of some of the most powerful countries or companies."

Significant writers and thinkers in the area include Ben Bagdikian, Noam Chomsky, Edward S. Herman and Robert W. McChesney.

Race

The political activist and one-time presidential candidate Jesse Jackson said in 1985 that the news media portray black people as "less intelligent than we are." The IQ Controversy, the Media and Public Policy, a book published by Stanley Rothman and Mark Snyderman, claimed to document bias in media coverage of scientific findings regarding race and intelligence. Snyderman and Rothman stated that media reports often erroneously reported that most experts believe that the genetic contribution to IQ is absolute or that most experts believe that genetics plays no role at all.

According to Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow in 1986, many stories of the crack crisis broke out in the media. In the stories, African Americans were featured as "crack whores." The deaths of the NBA player Len Bias and the NFL player Don Rogers from cocaine overdose only added to the media frenzy. Alexander claimed in her book, "Between October 1988 and October 1989, The Washington Post alone ran 1,565 stories about the 'drug scourge.'"

One example of this double standard is the comparison of the deaths of Michael Brown and Dillon Taylor. On August 9, 2014, news broke out that Brown, a young unarmed black man, was shot and killed by a white policeman. The story spread throughout news media, which explained that the incident had to do with race. Only two days later, Taylor, another young unarmed man, was shot and killed by a policeman. That story, however, did not get as highly publicized as Brown's. Taylor was white and Hispanic, but the police officer was black.

Research has shown that African Americans are over-represented in news reports on crime and that in the stories, they are more likely to be shown as the perpetrators of the crime than as the persons reacting to or suffering from it.

A 2017 report by Travis L. Dixon (of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) found that major media outlets tended to portray black families as dysfunctional and dependent, and white families were portrayed as stable. The portrayals may give the impression that poverty and welfare are primarily black issues. According to Dixon, that can reduce public support for social safety programs and lead to stricter welfare requirements. A 2018 study found that media portrayals of Muslims were substantially more negative than for other religious groups, even after relevant factors were controlled for. A 2019 study described media portrayals of minority women in crime news stories as based on "outdated and harmful stereotypes."

Another example of racial bias was the portrayal of African Americans in the 1992 riots in Los Angeles. The media presented the riots as being an African American problem and deemed African Americans solely responsible for the riots. However, according to reports, only 36% of those arrested during the riots were African Americans; 60% of the rioters and looters were Hispanics and whites.

Conversely, multiple commentators and newspaper articles have cited examples of the national media underreporting interracial hate crimes when they involve white victims, unlike when they involve black victims. Jon Ham, a vice president of the conservative John Locke Foundation, wrote that "local officials and editors often claim that mentioning the black-on-white nature of the event might inflame passion, but they never have those same qualms when it's white-on-black."

According to David Niven, of Ohio State University, research shows that mainstream American media show bias on only two issues: race and gender equality.

In a research conducted by Seong-Jae Min that tested racial bias in stories of missing children in the media, African American children were less represented between 2005 and 2007. According to the US Department of Justice, out of 800,000 yearly cases, 47% were "racial minorities" and were underreported. According to Dixon and Linz, the news media often reports cases where children of color are criminals but often report cases of white children being victims of crime.

Attention was brought to racial bias in the media following the case of Gabby Petito in September 2021. Many people were talking not only about Gabby and her case, but about missing white woman syndrome and the bias the media has against people of color. News outlets such as The New Yorker, The Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times published articles about Gabby's case as well as articles about the disproportionate amount of media coverage the case was receiving.

Gender

According to 2010 report, gender reporting is biased, with negative stories about women being more likely to make the news. Positive stories about men are more often reported than positive stories about women. However, according to Hartley, young girls are seen as youthful and therefore more "newsworthy."

In 2011, a study researching female media coverage during abortion protests found that 27.9% of media sources and subjects were women, despite them being the most prominent gender at the protests. The study also discussed how different media topics, in this case pro-choice protests, sometimes lead to biased reporting because of women's reluctance to speak up "in fear of misperceptions or repercussions."

The 1996 Summer Olympic Games showcased gender bias, with male athletes receiving more television coverage than female athletes in the major event.

According to a study done by Eran Shor, Arnout van de Rijt, and Babak Fotouhi, even after accounting for systemic gender disparity within occupation and public interest, women still receive disproportionate news coverage.

Politics

Numerous books and studies have addressed the question of political bias in the American media. Various broadcast and online outlets exhibit both liberal and conservative bias. Commentary, editorial and opinion is more biased than factual news reporting in the mainstream media, and concerns have been raised as the lines between commentary and journalism are increasingly blurred. In reaction to this, there has been a growth of independent fact-checking and algorithms to assess bias.

Liberal

Senator Barry Goldwater, a conservative, was the first Republican to allege liberal media bias during his 1964 presidential campaign. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "conservative media critics often claim that U.S. media skews toward the political left".

According to a study by Lars Willnat and David H. Weaver, professors of journalism at Indiana University, conducted via online interviews with 1,080 reporters between August and December 2013, 38.8% of US journalists identify as "leaning left" (28.1% identify as Democrats), 12.9% identify as "leaning right" (7.1% as Republicans), and 43.8% as "middle of the road" (50.2% as independents). The report noted that the fraction of Democratic journals in 2013 was the lowest since 1971, and down 8 percentage points since 2002; the trend is for more journalists to be politically non-aligned. The study also noted "The emergence of the problem of “fake news" and propaganda that is made possible by the dark underbelly of the digital age has combined with the Trump-driven hostility toward journalists to make the focus of this article even more timely."

An October 2017 Pew Research report found that 62% of stories involving US Republican President Donald Trump during his first 60 days in office had a negative assessment, compared to only 5% of stories with a positive assessment. By comparison, the study found that Democratic President Barack Obama received far more favorable coverage in his first 60 days in office; 42% of stories involving Obama during that period were identified as positive, and only 20% were identified as negative. A May 2017 study from Harvard University's Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy of Trump's first 100 days in office also identified a similar negative tone in coverage. The study found that 93% of CNN and NBC coverage of President Trump during the period was negative. The survey also found 91% of CBS coverage was negative and that 87% of The New York Times coverage was negative during Trump's first 100 days. For reference, the Kennedy School reported that the Financial Times of London, was also negative in 84% of articles over the same period, and the BBC was negative 74% of the time. Even Fox News, whose stated aim is to be conservative, was more negative of Trump than positive (52% to 48%).

An October 2018 Rasmussen Reports poll of 1,000 likely voters found 45% of Americans believed that when most reporters write about a congressional race, they are trying to help the Democratic candidate. Alternatively, only 11% believed that most reporters aimed to help Republican candidates.

A 2020 study in Science Advances found that, although a majority of journalists identify as liberals/Democrats, there is no evidence of a liberal media bias in which stories journalists chose to cover in their reporting.

A 2021 research paper published by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism found that American conservatives believe "that the American press blames, shames and ostracizes conservatives," citing media coverage of COVID-19 and Donald Trump, but that they were "not primarily upset that the media get facts wrong, nor even that journalists push a liberal policy agenda,".

Conservative

Perceived liberal bias was cited by Roger Ailes as a reason for setting up Fox News. From the late 20th century, a right-wing media ecosystem grew up in parallel to mainstream journalism, leading to an asymmetric polarization in conservative media. Whilst there has been research into The Wall Street Journal editorial page's adopting more conservative perspectives on economics since Rupert Murdoch's acquisition of the company, its news reporting is part of the journalistic mainstream and is committed primarily to factual reporting. New right-leaning media outlets, including Breitbart News, NewsMax, and WorldNetDaily have instead a core mission to promote a conservative or right-wing agenda, often (unlike The Wall Street Journal and other mainstream conservative journals) supporting a hierarchy based on race, religion, nationality, or gender. Analysis of social media shares in the 2016 election cycle shows that consumers of conservative media are much less likely than consumers of partisan liberal media to share mainstream sources, leading to an echo chamber effect with high insularity and drifting towards extremes. Mainstream and left-leaning media imposes reputational costs on those who propagate rumor and coalescences around corrected narratives, the conservative media ecosystem creates positive feedback for bias-confirming statements as a central feature of its normal operation.

Research finds that Fox News increases Republican votes and makes Republican politicians more partisan. A 2007 study, using the introduction of Fox News into local markets (1996–2000) as an instrumental variable, found that in the 2000 presidential election, "Republicans gained 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points in the towns that broadcast Fox News, which suggests that "Fox News convinced 3 to 28 percent of its viewers to vote Republican, depending on the audience measure." The results were confirmed by a 2015 study. A 2014 study, using the same instrumental variable, found congressional "representatives become less supportive of President Clinton in districts where Fox News begins broadcasting than similar representatives in similar districts where Fox News was not broadcast." Another 2014 paper found that Fox News viewing increased Republican vote shares among voters who identified as Republican or independent. A 2017 study, using channel positions as an instrumental variable, found "Fox News increases Republican vote shares by 0.3 points among viewers induced into watching 2.5 additional minutes per week by variation in position."

Cable news

Kenneth Tomlinson, while chairman of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, commissioned a $10,000 government study into Bill Moyers' PBS program, NOW. The results of the study indicated that there was no particular bias on PBS. Tomlinson chose to reject the results of the study, subsequently reducing time and funding for NOW with Bill Moyers, which Tomlinson regarded as a "left-wing" program, and then expanded a show hosted by Fox News correspondent Tucker Carlson. Some board members stated that his actions were politically motivated. Himself a frequent target of claims of bias (in this case, conservative bias), Tomlinson resigned from the CPB board on November 4, 2005. Regarding the claims of a left-wing bias, Moyers asserted in a Broadcasting & Cable interview that "If reporting on what's happening to ordinary people thrown overboard by circumstances beyond their control and betrayed by Washington officials is liberalism, I stand convicted."

According to former Fox News producer Charlie Reina, unlike the AP, CBS News, or ABC News, Fox News's editorial policy is set from the top down in the form of a daily memo: "[F]requently, Reina says, it also contains hints, suggestions and directives on how to slant the day's news—invariably, he said in 2003, in a way that was consistent with the politics and desires of the Bush administration." Fox News responded by denouncing Reina as a "disgruntled employee" with "an ax to grind." Andrew Sullivan wrote of Fox that "[o]ne alleged news network fed its audience a diet of lies, while contributing financially to the party that benefited from those lies." A similar top-down approach to dictating messaging is used at Sinclair Broadcast Group, which notably instructed all its local news anchors to run a conservative message in the main news segment. Its rapid growth through station group acquisitions—especially during the lead-up to the 2016 presidential elections—had provided an increasingly large platform promoting conservative views.

Nexstar Media Group, the US's largest owner of local television stations, specifically claimed to counter perceived cable news media bias by starting the NewsNation channel to replace the struggling general entertainment channel WGN America. Nexstar invested millions of dollars into news programming, and said they hired "rhetoricians" to monitor language used in their flagship newscast, NewsNation Prime, for evidence of bias. However, ratings were lower than the entertainment programming it replaced, the channel's interview with President Donald Trump was mocked by other outlets as being especially soft, and later it was disclosed that former Fox News Channel chief and Trump administration deputy chief of staff Bill Shine was brought on as a consultant. After the disclosure, the news director, managing editor, and vice president of news all resigned within one month, just as NewsNation was expanding its hours of coverage.

Asymmetric polarization

In Network Propaganda, Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris and Hal Roberts of Harvard's Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society use network analysis to analyze American media and explore why there is "often no overlap, no resemblance whatsoever between the news events reported in mainstream print and broadcast coverage [...] and the topics that get broadcast as news on the Fox network and its fellows on the right". By tracking citations and social media shares across various news outlets and correlating with editorial political leaning, they found that right-wing media sources had effectively segregated themselves into in an increasingly isolated silo, creating a propaganda feedback loop continually becoming more extreme and more partisan. They note that the right wing media "punish actors – be they media outlets or politicians and pundits – who insist on speaking truths that are inconsistent with partisan frames and narratives dominant within the ecosystem", and contrast this with a "reality check dynamic" that prevails in the mainstream media. They also note that liberal readers consume a much broader range of sources, whereas right wing media consumers rarely stray outside of the narrow right wing bubble.

Progressive media watchdog group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) has argued that accusations of liberal media bias are part of a conservative strategy, noting an article in the August 20, 1992 Washington Post, in which Republican party chair Rich Bond compared journalists to referees in a sporting match. "If you watch any great coach, what they try to do is 'work the refs.' Maybe the ref will cut you a little slack next time." A 1998 study from FAIR found that journalists are "mostly centrist in their political orientation"; 30% considered themselves to the left on social issues compared with 9% on the right, while 11% considered themselves to the left on economic issues compared with 19% on the right. The report argued that since journalists considered themselves to be centrists, "perhaps this is why an earlier survey found that they tended to vote for Bill Clinton in large numbers." FAIR uses this study to support the claim that media bias is propagated down from the management and that individual journalists are relatively neutral in their work.

In What Liberal Media? The Truth About Bias and the News (2003), Eric Alterman also disputes the belief in liberal media bias, and suggests that over-correcting for this belief resulted in the opposite.

Censorship of conservative content

Tech companies and social media sites have been accused of censorship by some conservative groups, although there is little or no evidence to support these claims.

At least one conservative theme, that of climate change denialism, is over-represented in the media, and some scientists have argued that media outlets have not done enough to combat false information. In November 2013, Nathan Allen, a PhD chemist and moderator on Reddit's science forum published an op-ed that argued that newspaper editors should refrain from publishing articles from people who deny the scientific consensus on climate change.

Conservatives have argued that Facebook and Twitter temporarily limiting the spread of the Hunter Biden laptop controversy on their platforms, even though parts of the story later turned out to be accurate, "proves Big Tech's bias".

Shadow banning

Claims of shadow banning of conservative social media accounts (manipulating algorithms to minimise the exposure and spread of specific content) were brought to the fore in 2016 when conservative news sites lashed out after a report from an unnamed Facebook employee on May 7 alleged that contractors for the social media giant were told to minimize links to their sites in its "trending news" column. The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard investigated and found no evidence of shadow-banning of conservatives.

Fact checking and fake news

Conservative outlets like The Weekly Standard and Big Government have criticized fact checking of conservative content as a perceived liberal attempt to control discourse. A 2019 study found that fake news sharing was less common than perceived, and that actual consumption of fake news was limited. Another 2019 study found that older, more conservative people were more likely to have shared fake news during the 2016 election season than moderates, younger adults, or "super liberals". An Oxford study has shown that deliberate use of fake news in the U.S. is primarily associated with the hard right. According to a 2019 study of fake news on Twitter during the 2016 election season, 80% of "all content from suspect sources was shared by less than 1 percent of the human tweeters sampled... Those users were disproportionately politically conservative, older and more highly engaged with political news".

The term "fake news" has been weaponized with the goal of undermining public trust in news media. President Donald Trump seized on the term "fake news" as a way of denigrating any story or outlet critical of him, even appearing to claim to have invented the term and handing out so-called "Fake News Awards" in 2017. Trump, followed by supporters such as Sean Hannity, uses the term "fake news" to describe any media coverage that casts him in a negative light. In 2018, Trump "described what he called the 'fake news' of the American press as 'The Enemy of the American people'", a phrase similar to one used by Stalin and other totalitarian leaders that also was reminiscent of Richard Nixon's inclusion of journalists on his "enemies list". In response, the United States Senate unanimously adopted a resolution which reaffirmed "the vital and indispensable role the free press serves" and was seen as a symbolic rebuke to Trump.

Presidential elections

In the 19th century, many American newspapers made no pretense to lack of bias and openly advocated for a political party. Big cities would often have competing newspapers, supporting various political parties. To some extent, that was mitigated by a separation between news and editorial. News-reporting was expected to be relatively neutral or at least factual, but editorial was openly the opinion of the publisher. Editorials might also be accompanied by an editorial cartoon, which would frequently lampoon the publisher's opponents.

In an editorial for The American Conservative, Patrick Buchanan wrote that reporting by "the liberal media establishment" on the Watergate scandal "played a central role in bringing down a president." Richard Nixon later complained, "I gave them a sword and they ran it right through me." Nixon's Vice-President Spiro Agnew attacked the media in a series of speeches, two of the most famous being written by White House aides William Safire and Buchanan himself, as "elitist" and "liberal." However, the media had also strongly criticized his Democratic predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, for his handling of the Vietnam War, which was a factor for him not seeking a second term.

In 2004, Steve Ansolabehere, Rebecca Lessem, and Jim Snyder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyzed the political orientation of endorsements by US newspapers. They found an upward trend in the average propensity to endorse a candidate, particularly an incumbent. In the 1940s and the 1950s, there was a clear advantage to Republican candidates, that advantage continuously eroded in subsequent decades to the extent that in the 1990s the authors found a slight Democratic lead in the average endorsement choice.

Riccardo Puglisi of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looked at the editorial choices of The New York Times from 1946 to 1997. He found that the Times displays Democratic partisanship, with some watchdog aspects. During presidential campaigns the Times systematically gives more coverage to Democratic topics of civil rights, health care, labor and social welfare but only when the incumbent president is a Republican. Those topics are classified as Democratic ones because Gallup polls show that average US citizens think that Democratic candidates would be better at handling problems related to them. According to Puglisi, the Times since 1960 displays a more symmetric type of watchdog behavior just because during presidential campaigns, it also gives more coverage to the typically-Republican issue of defense when the incumbent president is a Democrat but less so when the incumbent is a Republican.

John Lott and Kevin Hassett of the conservative thinktank American Enterprise Institute studied the coverage of economic news by looking at a panel of 389 US newspapers from 1991 to 2004 and a subsample of the two ten newspapers and the Associated Press from 1985 to 2004. For each release of official data about a set of economic indicators, the authors analyzed how newspapers decide to report on them, as reflected by the tone of the related headlines. The idea was to check whether newspapers display partisan bias, by giving more positive or negative coverage to the same economic figure, as a function of the political affiliation of the incumbent president. Controlling for the economic data being released, the authors find that there are 9.6–14.7% fewer positive stories when the incumbent president is a Republican.

According to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, a liberal watchdog group, the Democratic candidate John Edwards was falsely maligned and was not given coverage commensurate with his standing in presidential campaign coverage because his message questioned corporate power.

A 2000 meta-analysis of research in 59 quantitative studies of media bias in American presidential campaigns from 1948 through 1996 found that media bias tends to cancel out, leaving little or no net bias. The authors concluded, "It is clear that the major source of bias charges is the individual perceptions of media consumers and, in particular, media consumers of a particularly ideological bent."

It has also been acknowledged that media outlets have often used horse-race journalism with the intent of making elections more competitive. That form of political coverage involves diverting attention away from stronger candidates and hyping so-called dark horse contenders who seem more unlikely to win when the election cycle begins. Benjamin Disraeli used the term "dark horse" to describe horse racing in 1831 in The Young Duke: "a dark horse which had never been thought of and which the careless St. James had never even observed in the list, rushed past the grandstand in sweeping triumph." The political analyst Larry Sabato stated in his 2006 book Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections that Disraeli's description of dark horses "now fits in neatly with the media's trend towards horse-race journalism and penchant for using sports analogies to describe presidential politics."

Often unlike national media, political science scholars seek to compile long-term data and research on the impact of political issues and voting in U.S. presidential elections, producing in-depth articles breaking down the issues.

2000

During the course of the election, some pundits accused the mainstream media of distorting facts in an effort to help Texas Governor George W. Bush win the election after Bush and Al Gore officially launched their campaigns in 1999. Peter Hart and Jim Naureckas, two commentators for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, called the media "serial exaggerators" and argued that several media outlets were constantly exaggerating criticism of Gore, such as by falsely claiming that Gore lied when he claimed he spoke in an overcrowded science class in Sarasota, Florida, and giving Bush a pass on certain issues, such as the fact that Bush had wildly exaggerated how much money he signed into the annual Texas state budget to help the uninsured during his second debate with Gore in October 2000. In the April 2000 issue of Washington Monthly, the columnist Robert Parry also argued that several media outlets exaggerated Gore's supposed claim that he "discovered" the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York, during a campaign speech in Concord, New Hampshire, on November 30, 1999, when he had claimed only that he "found" it after it was already evacuated in 1978 after chemical contamination. The Rolling Stone columnist Eric Boehlert also argued that media outlets exaggerated criticism of Gore as early as July 22, 1999, when Gore, known for being an environmentalist, had a friend release 500 million gallons of water into a drought-stricken river to help keep his boat afloat for a photo shoot. Media outlets, however, exaggerated the actual number of gallons that were released to four billion.

2008

In the 2008 presidential election, media outlets were accused of discrediting Barack Obama's opponents in an effort to help him win the Democratic primary and later the general election. At the February debate, Tim Russert of NBC News was criticized for what some perceived as disproportionately-tough questioning of the Democratic presidential contender Hillary Clinton. Among the questions, Russert had asked Clinton but not Obama to provide the name of the new Russian president, who was Dmitry Medvedev. That was later parodied on Saturday Night Live.

In October 2007, liberal commentators accused Russert of harassing Clinton over the issue of supporting drivers' licenses for illegal immigrants.

On April 16, 2008, ABC News hosted a debate in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The moderators Charles Gibson and George Stephanopoulos were criticized by viewers, bloggers and media critics for the poor quality of their questions. Many viewers said they considered some of the questions to be irrelevant compared to the importance of the faltering economy or the Iraq War. Included in that category were continued questions about Obama's former pastor, Clinton's assertion that she had to duck sniper fire in Bosnia more than a decade earlier, and Obama's failure to wear an American flag pin. The moderators focused on campaign gaffes, and some believed that they focused too much on Obama. Stephanopoulos defended their performance by claiming that "Senator Obama was the front-runner" and that the questions were "not inappropriate or irrelevant at all."

In an op-ed published on April 27, 2008, in The New York Times, Elizabeth Edwards wrote that the media covered much more of "the rancor of the campaign" and "amount of money spent" than "the candidates' priorities, policies and principles." Author Erica Jong commented that "our press has become a sea of triviality, meanness and irrelevant chatter." A Gallup poll released on May 29, 2008, also estimated that more Americans felt the media was being harder on Clinton than they were on Obama.

In a joint study by the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University and the Project for Excellence in Journalism, the authors found disparate treatment by the three major cable networks of the Republican and Democratic candidates during the earliest five months of presidential primaries in 2007: "The CNN programming studied tended to cast a negative light on Republican candidates—by a margin of three-to-one. Four-in-ten stories (41%) were clearly negative while just 14% were positive and 46% were neutral. The network provided negative coverage of all three main candidates with McCain faring the worst (63% negative) and Romney faring a little better than the others only because a majority of his coverage was neutral. It is not that Democrats, other than Obama, fared well on CNN either. Nearly half of the Illinois Senator's stories were positive (46%), vs. just 8% that were negative. But both Clinton and Edwards ended up with more negative than positive coverage overall. So while coverage for Democrats overall was a bit more positive than negative, that was almost all due to extremely favorable coverage for Obama."

A poll of likely presidential election voters released on March 14, 2007, by Zogby International reported that 83 percent of those surveyed believed in media bias, with 64 percent of respondents of the opinion the bias to favor liberals and 28 percent of respondents believing the bias to be conservative. In August 2008, the ombudsman of The Washington Post wrote that it had published almost three times as many front-page stories about Obama than it had about McCain since Obama won the Democratic party nomination that June. In September 2008 a Rasmussen poll found that 68 percent of voters believed that "most reporters try to help the candidate they want to win," and 49 percent of respondents stated that the reporters were helping Obama to get elected, but only 14 percent said the same about McCain. A further 51 percent said that the press was actively "trying to hurt" Republican vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin with negative coverage. In October 2008, Washington Post media correspondent Howard Kurtz reported that Palin was again on the cover of Newsweek "but with the most biased campaign headline I've ever seen."

After the election was over, the ombudsman Deborah Howell reviewed the coverage of the Post and concluded that it had been slanted toward Obama. "The Post provided a lot of good campaign coverage, but readers have been consistently critical of the lack of probing issues coverage and what they saw as a tilt toward Democrat Barack Obama. My surveys, which ended on Election Day, show that they are right on both counts." Over the course of the campaign, the Post printed 594 "issues stories" and 1,295 "horse-race stories." There were more positive opinion pieces on Obama than McCain (32 to 13) and more negative pieces about McCain than Obama (58 to 32). Overall, more news stories were dedicated to Obama than McCain. Howell said that the results of her survey were comparable to those reported by the Project for Excellence in Journalism for the national media. (That report, issued on October 22, 2008, found that "coverage of McCain has been heavily unfavorable," with 57% of the stories issued after the conventions being negative and only 14% being positive. For the same period, 36% of the stories on Obama were positive, 35% were neutral or mixed, and 29% were negative.) She rated the biographical stories of the Post to be generally quite good, she concluded, "Obama deserved tougher scrutiny than he got, especially of his undergraduate years, his start in Chicago and his relationship with Antoin 'Tony' Rezko, who was convicted this year of influence-peddling in Chicago. The Post did nothing on Obama's acknowledged drug use as a teenager."

Various critics, particularly Hudson, have shown concern over the link between the news media's reporting and what they see as the trivialised nature of American elections. Hudson argued that America's news media elections coverage damages the democratic process. He argues that elections are centered on candidates, whose advancement depends on funds, personality and sound-bites, rather than serious political discussion or policies offered by parties. His argument is that it is on the media which Americans are dependent for information about politics (this is of course true almost by definition) and that they are therefore greatly influenced by the way the media report, which concentrates on short sound-bites, gaffes by candidates, and scandals. The reporting of elections avoids complex issues or issues which are time-consuming to explain. Of course, important political issues are generally both complex and time-consuming to explain, so are avoided.

Hudson blames this style of media coverage, at least partly, for trivialised elections:

"The bites of information voters receive from both print and electronic media are simply insufficient for constructive political discourse ... candidates for office have adjusted their style of campaigning in response to this tabloid style of media coverage... modern campaigns are exercises in image manipulation.... Elections decided on sound bites, negative campaign commercials, and sensationalised exposure of personal character flaws provide no meaningful direction for government."

2016

Studies have shown that all other 2016 candidates received vastly less media coverage than Donald Trump. Trump received more extensive media coverage than Ted Cruz, John Kasich, Hillary Clinton, and Bernie Sanders combined when they were the only primary candidates left in the race. The Democratic primary received substantially less coverage than the Republican primary. Sanders received the most positive coverage of any candidate overall, but his opponent in the Democratic primary, Hillary Clinton, received the most negative coverage. Among the general election candidates, Trump received inordinate amounts of coverage on his policies and issues and on his personal character and life, but Clinton's emails controversy was a dominant feature of her coverage and earned more media coverage than all of her policy positions combined.

Foreign policy

In addition to philosophical or economic biases, there are also subject biases, including criticism of media coverage about US foreign policy issues as being overly centered in Washington, DC. Coverage is variously cited as being "beltway centrism," framed in terms of domestic politics and established policy positions, following only Washington's 'Official Agendas', and mirroring only a "Washington Consensus." Regardless of the criticism, according to the Columbia Journalism Review, "No news subject generates more complaints about media objectivity than the Middle East in general and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in particular."

Vietnam War

Arab–Israeli conflict

Stephen Zunes wrote that "mainstream and conservative Jewish organizations have mobilized considerable lobbying resources, financial contributions from the Jewish community, and citizen pressure on the news media and other forums of public discourse in support of the Israeli government."

According to the professor of journalism Eric Alterman, debate among Middle East pundits "is dominated by people who cannot imagine criticizing Israel." In 2002, he listed 56 columnists and commentators who can be counted on to support Israel "reflexively and without qualification." Alterman identified only five pundits who consistently criticize Israeli behavior or endorse pro-Arab positions. Journalists described as pro-Israel by Mearsheimer and Walt include The New York Times' William Safire, A.M. Rosenthal, David Brooks, and Thomas Friedman; The Washington Post's Jim Hoagland, Robert Kagan, Charles Krauthammer, and George Will; and the Los Angeles Times' Max Boot, Jonah Goldberg, and Jonathan Chait.

The 2007 book The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy argued that there is a media bias in favor of Israel. It stated that a former spokesman for the Israeli consulate in New York said, "Of course, a lot of self-censorship goes on. Journalists, editors, and politicians are going to think twice about criticizing Israel if they know they are going to get thousands of angry calls in a matter of hours. The Jewish lobby is good at orchestrating pressure."

The journalist Michael Massing wrote in 2006, "Jewish organizations are quick to detect bias in the coverage of the Middle East, and quick to complain about it. That's especially true of late. As The Forward observed in late April [2002], 'rooting out perceived anti-Israel bias in the media has become for many American Jews the most direct and emotional outlet for connecting with the conflict 6,000 miles away.'"

The Forward related how one individual felt:

"'There's a great frustration that American Jews want to do something,' said Ira Youdovin, executive vice president of the Chicago Board of Rabbis. 'In 1947, some number would have enlisted in the Haganah,' he said, referring to the pre-state Jewish armed force. 'There was a special American brigade. Nowadays you can't do that. The battle here is the hasbarah war,' Youdovin said, using a Hebrew term for public relations. 'We're winning, but we're very much concerned about the bad stuff.'"

A 2003 Boston Globe article on the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America media watchdog group by Mark Jurkowitz argued, "To its supporters, CAMERA is figuratively—and perhaps literally—doing God's work, battling insidious anti-Israeli bias in the media. But its detractors see CAMERA as a myopic and vindictive special interest group trying to muscle its views into media coverage."

Iraq War

In 2003, a study released by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting stated the network news disproportionately focused on pro-war sources and left out many anti-war sources. According to the study, 64% of total sources were in favor of the Iraq War, and total anti-war sources made up 10% of the media (only 3% of US sources were anti-war). The study stated that "viewers were more than six times as likely to see a pro-war source as one who was anti-war; with U.S. guests alone, the ratio increases to 25 to 1."

In February 2004, a study was released by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting]. According to the study, which took place during October 2003, current or former government or military officials accounted for 76 percent of all 319 sources for news stories about Iraq that aired on network news channels.

News sources

..."balanced" coverage that plagues American journalism and which leads to utterly spineless reporting with no edge. The idea seems to be that journalists are allowed to go out to report, but when it comes time to write, we are expected to turn our brains off and repeat the spin from both sides. God forbid we should... attempt to fairly assess what we see with our own eyes. "Balanced" is not fair, it's just an easy way of avoiding real reporting... and shirking our responsibility to inform readers.

Ken Silverstein in Harper's Magazine, 2007.

A widely cited public opinion study documented a correlation between news source and certain misconceptions about the Iraq War. Conducted by the Program on International Policy Attitudes in October 2003, the poll asked Americans whether they believed statements about the Iraq War that were known to be false. Respondents were also asked for their primary news source: Fox News, CBS, NBC, ABC, CNN, "Print sources," or NPR. By cross-referencing the respondents to their primary news source, the study showed that more Fox News watchers held the misconceptions about the Iraq War. The director of Program on International Policy (PIPA), Stephen Kull, said, "While we cannot assert that these misconceptions created the support for going to war with Iraq, it does appear likely that support for the war would be substantially lower if fewer members of the public had these misperceptions."

China

In November 2018, Senator Chris Coons joined Senators Elizabeth Warren, Marco Rubio, and a bipartisan group of lawmakers in sending a letter to the Trump administration raising concerns about China's undue influence over US media outlets and academic institutions: "In American news outlets, Beijing has used financial ties to suppress negative information about the CCP. In the past four years, multiple media outlets with direct or indirect financial ties to China allegedly decided not to publish stories on wealth and corruption in the CCP. In one case, an editor resigned due to mounting self-censorship in the outlet's China coverage."

Accusations between competitors

Jonathan M. Ladd, who has conducted intensive studies of media trust and media bias, concluded that the primary cause of widespread popular belief in media bias is media telling their audience that other particular media are biased. People who are told that a medium is biased tend to believe that it is biased, and this belief is unrelated to whether that medium is actually biased or not. The only other factor with as strong an influence on belief that media is biased is extensive coverage of celebrities. A majority of people see such media as biased, while at the same time preferring media with extensive coverage of celebrities.

Kenneth Kim, in Communication Research Reports, argued that the overriding cause of popular belief in media bias is a media vs. media worldview. He used statistics to show that people see news content as neutral, fair, or biased based on its relation to news sources that report opposite views. Kim labeled this phenomenon HMP (hostile media perception). His results show that people are likely to process content in defensive ways based on the framing of this content in other media.

Watchdogs and ranking groups

AllSides assesses ideological biases of online sources to produce media bias charts, and presents similar stories from different perspectives.

The Pew Research Center produced a guide to the political leanings of readers of several news outlets as part of a larger report on political polarization in the United States.

Reporters Without Borders has said that the US media lost a great deal of freedom between the 2004 and 2006 indices, citing the Judith Miller case and similar cases and laws restricting the confidentiality of sources as the main factors. They also cite the fact that reporters who question the American-led so called war on terror are sometimes regarded as suspicious. They rank the US as 53rd out of 168 countries in freedom of the press, comparable to Japan and Uruguay, but below all but one European Union country (Poland) and below most OECD countries (those that accept democracy and free markets). In the 2008 ranking, the U.S. moved up to 36, between Taiwan and Macedonia, but still far below its ranking in the late 20th century as a world leader in having a free and unbiased press.[citation needed] The U.S. briefly recovered in 2009 and 2010, rising to 20th place, but declined again and has maintained a position in the mid-40s from 2013 to 2018.

Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) and Media Matters for America work from a progressive viewpoint, Accuracy in Media and Media Research Center are conservative.

Groups such as FactCheck argue that the media frequently get the facts wrong because they rely on biased sources of information. That includes using information provided to them from both parties.