| Holocene | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronology | ||||||

| ||||||

| Etymology | ||||||

| Name formality | Formal | |||||

| Usage information | ||||||

| Celestial body | Earth | |||||

| Regional usage | Global (ICS) | |||||

| Time scale(s) used | ICS Time Scale | |||||

| Definition | ||||||

| Chronological unit | Epoch | |||||

| Stratigraphic unit | Series | |||||

| Time span formality | Formal | |||||

| Lower boundary definition | End of the Younger Dryas stadial. | |||||

| Lower boundary GSSP | NGRIP2 ice core, Greenland 75.1000°N 42.3200°W | |||||

| Lower GSSP ratified | 2008 | |||||

| Upper boundary definition | Present day | |||||

| Upper boundary GSSP | N/A N/A | |||||

| Upper GSSP ratified | N/A | |||||

The Holocene (/ˈhɒl.əsiːn, -oʊ-, ˈhoʊ.lə-, -loʊ-/) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,700 years before 2000 CE[a] (11,650 cal years BP, 9700 BCE or 300 HE). It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene together form the Quaternary period. The Holocene has been identified with the current warm period, known as MIS 1. It is considered by some to be an interglacial period within the Pleistocene Epoch, called the Flandrian interglacial.

The Holocene corresponds with the rapid proliferation, growth and impacts of the human species worldwide, including all of its written history, technological revolutions, development of major civilizations, and overall significant transition towards urban living in the present. The human impact on modern-era Earth and its ecosystems may be considered of global significance for the future evolution of living species, including approximately synchronous lithospheric evidence, or more recently hydrospheric and atmospheric evidence of the human impact. In July 2018, the International Union of Geological Sciences split the Holocene Epoch into three distinct ages based on the climate, Greenlandian (11,700 years ago to 8,200 years ago), Northgrippian (8,200 years ago to 4,200 years ago) and Meghalayan (4,200 years ago to the present), as proposed by International Commission on Stratigraphy. The oldest age, the Greenlandian was characterized by a warming following the preceding ice age. The Northgrippian Age is known for vast cooling due to a disruption in ocean circulations that was caused by the melting of glaciers. The most recent age of the Holocene is the present Meghalayan, which began with extreme drought that lasted around 200 years.

Etymology

The word Holocene was formed from two Ancient Greek words. Holos (ὅλος) is the Greek word for "whole". "Cene" comes from the Greek word kainos (καινός), meaning "new". The concept is that this epoch is "entirely new". The suffix '-cene' is used for all the seven epochs of the Cenozoic Era.

Overview

The International Commission on Stratigraphy has defined the Holocene as starting approximately 11,700 years before 2000 CE (11,650 cal years BP, or 9,700 BCE). The Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS) regards the term 'recent' as an incorrect way of referring to the Holocene, preferring the term 'modern' instead to describe current processes. It also observes that the term 'Flandrian' may be used as a synonym for Holocene, although it is becoming outdated. The International Commission on Stratigraphy, however, considers the Holocene an epoch following the Pleistocene and specifically following the last glacial period. Local names for the last glacial period include the Wisconsinan in North America, the Weichselian in Europe, the Devensian in Britain, the Llanquihue in Chile and the Otiran in New Zealand."

The Holocene can be subdivided into five time intervals, or chronozones, based on climatic fluctuations:

- Preboreal (10 ka–9 ka BP),

- Boreal (9 ka–8 ka BP),

- Atlantic (8 ka–5 ka BP),

- Subboreal (5 ka–2.5 ka BP) and

- Subatlantic (2.5 ka BP–present).

- Note: "ka BP" means "kilo-annum Before Present", i.e. 1,000 years before 1950 (non-calibrated C14 dates)

Geologists working in different regions are studying sea levels, peat bogs and ice-core samples, using a variety of methods, with a view toward further verifying and refining the Blytt–Sernander sequence. This is a classification of climatic periods initially defined by plant remains in peat mosses. Though the method was once thought to be of little interest, based on 14C dating of peats that was inconsistent with the claimed chronozones, investigators have found a general correspondence across Eurasia and North America. The scheme was defined for Northern Europe, but the climate changes were claimed to occur more widely. The periods of the scheme include a few of the final pre-Holocene oscillations of the last glacial period and then classify climates of more recent prehistory.

Paleontologists have not defined any faunal stages for the Holocene. If subdivision is necessary, periods of human technological development, such as the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age, are usually used. However, the time periods referenced by these terms vary with the emergence of those technologies in different parts of the world.

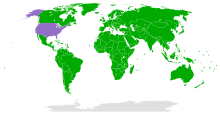

According to some scholars, a third epoch of the Quaternary, the Anthropocene, has now begun. This term is used to denote the present time-interval in which many geologically significant conditions and processes have been profoundly altered by human activities. The 'Anthropocene' (a term coined by Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in 2000) is not a formally defined geological unit. The Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy of the International Commission on Stratigraphy has a working group to determine whether it should be. In May 2019, members of the working group voted in favour of recognizing the Anthropocene as formal chrono-stratigraphic unit, with stratigraphic signals around the mid-twentieth century CE as its base. The exact criteria have still to be determined, after which the recommendation also has to be approved by the working group's parent bodies (ultimately the International Union of Geological Sciences).

Geology

The Holocene is a geologic epoch that follows directly after the Pleistocene. Continental motions due to plate tectonics are less than a kilometre over a span of only 10,000 years. However, ice melt caused world sea levels to rise about 35 m (115 ft) in the early part of the Holocene and another 30 m in the later part of the Holocene. In addition, many areas above about 40 degrees north latitude had been depressed by the weight of the Pleistocene glaciers and rose as much as 180 m (590 ft) due to post-glacial rebound over the late Pleistocene and Holocene, and are still rising today.

The sea-level rise and temporary land depression allowed temporary marine incursions into areas that are now far from the sea. For example, marine fossils from the Holocene epoch have been found in locations such as Vermont and Michigan. Other than higher-latitude temporary marine incursions associated with glacial depression, Holocene fossils are found primarily in lakebed, floodplain, and cave deposits. Holocene marine deposits along low-latitude coastlines are rare because the rise in sea levels during the period exceeds any likely tectonic uplift of non-glacial origin.

Post-glacial rebound in the Scandinavia region resulted in a shrinking Baltic Sea. The region continues to rise, still causing weak earthquakes across Northern Europe. An equivalent event in North America was the rebound of Hudson Bay, as it shrank from its larger, immediate post-glacial Tyrrell Sea phase, to its present boundaries.

Climate

The climate throughout the Holocene has shown significant variability despite ice core records from Greenland suggesting a more stable climate following the preceding ice age. Marine chemical fluxes during the Holocene were lower than during the Younger Dryas, but were still considerable enough to imply notable changes in the climate. The Greenland ice core records indicate that climate changes became more regional and had a larger effect on the mid-to-low latitudes and mid-to-high latitudes after ~5600 B.P. During the transition from the last glacial to the Holocene, the Huelmo–Mascardi Cold Reversal in the Southern Hemisphere began before the Younger Dryas, and the maximum warmth flowed south to north from 11,000 to 7,000 years ago. It appears that this was influenced by the residual glacial ice remaining in the Northern Hemisphere until the later date.

The Holocene climatic optimum (HCO) was a period of warming throughout the globe. It has been suggested that the warming was not uniform across the world. Ice core measurements imply that the sea surface temperature (SST) gradient east of New Zealand, across the subtropical front (STF), was around 2 degrees Celsius. This temperature gradient is significantly less than modern times, which is around 6 degrees Celsius. A study utilizing five SST proxies from 37°S to 60°S latitude confirmed that the strong temperature gradient was confined to the area immediately south of the STF, and is correlated with reduced westerly winds near New Zealand. From the 10th-14th century, the climate was similar to that of modern times during a period known as the Medieval climate optimum, or the Medieval warm period (MWP). It was found that the warming that is taking place in current years is both more frequent and more spatially homogeneous than what was experienced during the MWP. A warming of +1 degree Celsius occurs 5–40 times more frequently in modern years than during the MWP. The major forcing during the MWP was due to greater solar activity, which led to heterogeneity compared to the greenhouse gas forcing of modern years that leads to more homogeneous warming. This was followed by the Little Ice Age, from the 13th or 14th century to the mid-19th century.

The temporal and spatial extent of climate change during the Holocene is an area of considerable uncertainty, with radiative forcing recently proposed to be the origin of cycles identified in the North Atlantic region. Climate cyclicity through the Holocene (Bond events) has been observed in or near marine settings and is strongly controlled by glacial input to the North Atlantic. Periodicities of ≈2500, ≈1500, and ≈1000 years are generally observed in the North Atlantic. At the same time spectral analyses of the continental record, which is remote from oceanic influence, reveal persistent periodicities of 1,000 and 500 years that may correspond to solar activity variations during the Holocene Epoch. A 1,500-year cycle corresponding to the North Atlantic oceanic circulation may have had widespread global distribution in the Late Holocene.

Ecological developments

Animal and plant life have not evolved much during the relatively short Holocene, but there have been major shifts in the richness and abundance of plants and animals. A number of large animals including mammoths and mastodons, saber-toothed cats like Smilodon and Homotherium, and giant sloths went extinct in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. The extinction of some megafauna in America could be attributed to the Clovis people; this culture was known for "Clovis points" which were fashioned on spears for hunting animals. Shrubs, herbs, and mosses had also changed in relative abundance from the Pleistocene to Holocene, identified by permafrost core samples.

Throughout the world, ecosystems in cooler climates that were previously regional have been isolated in higher altitude ecological "islands".

The 8.2-ka event, an abrupt cold spell recorded as a negative excursion in the δ18O record lasting 400 years, is the most prominent climatic event occurring in the Holocene Epoch, and may have marked a resurgence of ice cover. It has been suggested that this event was caused by the final drainage of Lake Agassiz, which had been confined by the glaciers, disrupting the thermohaline circulation of the Atlantic. This disruption was the result of an ice dam over Hudson Bay collapsing sending cold lake Agassiz water into the North Atlantic ocean. Furthermore, studies show that the melting of Lake Agassiz led to sea-level rise which flooded the North American coastal landscape. The basal peat plant was then used to determine the resulting local sea-level rise of 0.20-0.56m in the Mississippi Delta. Subsequent research, however, suggested that the discharge was probably superimposed upon a longer episode of cooler climate lasting up to 600 years and observed that the extent of the area affected was unclear.

Human developments

The beginning of the Holocene corresponds with the beginning of the Mesolithic age in most of Europe. In regions such as the Middle East and Anatolia, the term Epipaleolithic is preferred in place of Mesolithic, as they refer to approximately the same time period. Cultures in this period include Hamburgian, Federmesser, and the Natufian culture, during which the oldest inhabited places still existing on Earth were first settled, such as Tell es-Sultan (Jericho) in the Middle East. There is also evolving archeological evidence of proto-religion at locations such as Göbekli Tepe, as long ago as the 9th millennium BC.

The preceding period of the Late Pleistocene had already brought advancements such as the bow and arrow, creating more efficient forms of hunting and replacing spear throwers. In the Holocene, however, the domestication of plants and animals allowed humans to develop villages and towns in centralized locations. Archaeological data shows that between 10,000 to 7,000 BP rapid domestication of plants and animals took place in tropical and subtropical parts of Asia, Africa, and Central America. The development of farming allowed humans to transition away from hunter-gatherer nomadic cultures, which did not establish permanent settlements, to a more sustainable sedentary lifestyle. This form of lifestyle change allowed humans to develop towns and villages in centralized locations, which gave rise to the world known today. It is believed that the domestication of plants and animals began in the early part of the Holocene in the tropical areas of the planet. Because these areas had warm, moist temperatures, the climate was perfect for effective farming. Culture development and human population change, specifically in South America, has also been linked to spikes in hydroclimate resulting in climate variability in the mid-Holocene (8.2 - 4.2 k cal BP). Climate change on seasonality and available moisture also allowed for favorable agricultural conditions which promoted human development for Maya and Tiwanaku regions.

Extinction event

The Holocene extinction, otherwise referred to as the sixth mass extinction or Anthropocene extinction, is an ongoing extinction event of species during the present Holocene epoch (with the more recent time sometimes called Anthropocene) as a result of human activity. The included extinctions span numerous families of bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. With widespread degradation of highly biodiverse habitats such as coral reefs and rainforests, as well as other areas, the vast majority of these extinctions are thought to be undocumented, as the species are undiscovered at the time of their extinction, or no one has yet discovered their extinction. The current rate of extinction of species is estimated at 100 to 1,000 times higher than natural background extinction rates.