Artist's impression of the Gaia spacecraft | |

| Mission type | Astrometric observatory |

|---|---|

| Operator | ESA |

| COSPAR ID | 2013-074A |

| SATCAT no. | 39479 |

| Website | www |

| Mission duration | 9 years, 10 months and 12 days (in progress) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | |

| Launch mass | 2,029 kg (4,473 lb) |

| Dry mass | 1,392 kg (3,069 lb) |

| Payload mass | 710 kg (1,570 lb) |

| Dimensions | 4.6 m × 2.3 m (15.1 ft × 7.5 ft) |

| Power | 1,910 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 19 December 2013, 09:12:14 UTC |

| Rocket | Soyuz ST-B/Fregat-MT |

| Launch site | Kourou ELS |

| Contractor | Arianespace |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | decommissioned |

| Deactivated | 2025 (planned) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Sun–Earth L2 |

| Regime | Lissajous orbit |

| Periapsis altitude | 263,000 km (163,000 mi) |

| Apoapsis altitude | 707,000 km (439,000 mi) |

| Period | 180 days |

| Epoch | 2014 |

| Main telescope | |

| Type | Three-mirror anastigmat |

| Diameter | 1.45 m × 0.5 m (4 ft 9 in × 1 ft 8 in) |

| Collecting area | 0.7 m2 |

| Transponders | |

| Band | |

| Bandwidth |

|

| Instruments | |

| |

ESA insignia for Gaia | |

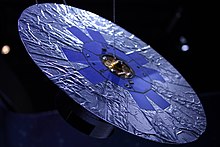

Gaia is a space observatory of the European Space Agency (ESA), launched in 2013 and expected to operate until 2025. The spacecraft is designed for astrometry: measuring the positions, distances and motions of stars with unprecedented precision, and the positions of exoplanets by measuring attributes about the stars they orbit such as their apparent magnitude and color. The mission aims to construct by far the largest and most precise 3D space catalog ever made, totalling approximately 1 billion astronomical objects, mainly stars, but also planets, comets, asteroids and quasars, among others.

To study the precise position and motion of its target objects, the spacecraft monitored each of them about 70 times over the five years of the nominal mission (2014–2019), and continues to do so during its extension. The spacecraft has enough micro-propulsion fuel to operate until the second quarter of 2025. As its detectors are not degrading as fast as initially expected, the mission can be further extended. Gaia targets objects brighter than magnitude 20 in a broad photometric band that covers the extended visual range between near-UV and near infrared; such objects represent approximately 1% of the Milky Way population. Additionally, Gaia is expected to detect thousands to tens of thousands of Jupiter-sized exoplanets beyond the Solar System by using the astrometry method, 500,000 quasars outside this galaxy and tens of thousands of known and new asteroids and comets within the Solar System.

The Gaia mission continues to create a precise three-dimensional map of astronomical objects throughout the Milky Way and map their motions, which encode the origin and subsequent evolution of the Milky Way. The spectrophotometric measurements provide detailed physical properties of all stars observed, characterizing their luminosity, effective temperature, gravity and elemental composition. This massive stellar census is providing the basic observational data to analyze a wide range of important questions related to the origin, structure and evolutionary history of the Milky Way galaxy.

The successor to the Hipparcos mission (operational 1989–1993), Gaia is part of ESA's Horizon 2000+ long-term scientific program. Gaia was launched on 19 December 2013 by Arianespace using a Soyuz ST-B/Fregat-MT rocket flying from Kourou in French Guiana. The spacecraft currently operates in a Lissajous orbit around the Sun–Earth L2 Lagrangian point.

History

The Gaia space telescope has its roots in ESA's Hipparcos mission (1989–1993). Its mission was proposed in October 1993 by Lennart Lindegren (Lund Observatory, Lund University, Sweden) and Michael Perryman (ESA) in response to a call for proposals for ESA's Horizon Plus long-term scientific programme. It was adopted by ESA's Science Programme Committee as cornerstone mission number 6 on 13 October 2000, and the B2 phase of the project was authorised on 9 February 2006, with EADS Astrium taking responsibility for the hardware. The name "Gaia" was originally derived as an acronym for Global Astrometric Interferometer for Astrophysics. This reflected the optical technique of interferometry that was originally planned for use on the spacecraft. While the working method evolved during studies and the acronym is no longer applicable, the name Gaia remained to provide continuity with the project.

The total cost of the mission is around €740 million (~ $1 billion), including the manufacture, launch and ground operations. Gaia was completed two years behind schedule and 16% above its initial budget, mostly due to the difficulties encountered in polishing Gaia's ten silicon carbide mirrors and assembling and testing the focal plane camera system.

Objectives

The Gaia space mission has the following objectives:

- To determine the intrinsic luminosity of a star requires knowledge of its distance. One of the few ways to achieve this without physical assumptions is through the star's parallax, but atmospheric effects and instrumental biases degrade the precision of parallax measurements. For instance, Cepheid variables are used as standard candles to measure distances to galaxies, but their own distances are poorly known. Thus, quantities depending on them, such as the speed of expansion of the universe, remain inaccurate.

- Observations of the faintest objects will provide a more complete view of the stellar luminosity function. Gaia will observe 1 billion stars and other bodies, representing 1% of such bodies in the Milky Way galaxy. All objects up to a certain magnitude must be measured in order to have unbiased samples.

- To permit a better understanding of the more rapid stages of stellar evolution (such as the classification, frequency, correlations and directly observed attributes of rare fundamental changes and of cyclical changes). This has to be achieved by detailed examination and re-examination of a great number of objects over a long period of operation. Observing a large number of objects in the galaxy is also important to understand the dynamics of this galaxy.

- Measuring the astrometric and kinematic properties of a star is necessary in order to understand the various stellar populations, especially the most distant.

Spacecraft

Gaia was launched by Arianespace, using a Soyuz ST-B rocket with a Fregat-MT upper stage, from the Ensemble de Lancement Soyouz at Kourou in French Guiana on 19 December 2013 at 09:12 UTC (06:12 local time). The satellite separated from the rocket's upper stage 43 minutes after launch at 09:54 UTC.

The craft headed towards the Sun–Earth Lagrange point L2 located approximately 1.5 million kilometres from Earth, arriving there 8 January 2014. The L2 point provides the spacecraft with a very stable gravitational and thermal environment. There, it uses a Lissajous orbit that avoids blockage of the Sun by the Earth, which would limit the amount of solar energy the satellite could produce through its solar panels, as well as disturb the spacecraft's thermal equilibrium. After launch, a 10-metre-diameter sunshade was deployed. The sunshade always faces the Sun, thus keeping all telescope components cool and powering Gaia using solar panels on its surface. These factors and the materials used in its creation allow Gaia to function in conditions between -170°C and 70°C.

Scientific instruments

The Gaia payload consists of three main instruments:

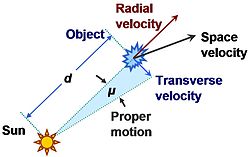

- The astrometry instrument (Astro) precisely determines the positions of all stars brighter than magnitude 20 by measuring their angular position. By combining the measurements of any given star over the five-year mission, it will be possible to determine its parallax, and therefore its distance, and its proper motion—the velocity of the star projected on the plane of the sky.

- The photometric instrument (BP/RP) allows the acquisition of luminosity measurements of stars over the 320–1000 nm spectral band, of all stars brighter than magnitude 20. The blue and red photometers (BP/RP) are used to determine stellar properties such as temperature, mass, age and elemental composition. Multi-colour photometry is provided by two low-resolution fused-silica prisms dispersing all the light entering the field of view in the along-scan direction prior to detection. The Blue Photometer (BP) operates in the wavelength range 330–680 nm; the Red Photometer (RP) covers the wavelength range 640–1050 nm.

- The Radial-Velocity Spectrometer (RVS) is used to determine the velocity of celestial objects along the line of sight by acquiring high-resolution spectra in the spectral band 847–874 nm (field lines of calcium ion) for objects up to magnitude 17. Radial velocities are measured with a precision between 1 km/s (V=11.5) and 30 km/s (V=17.5). The measurements of radial velocities are important to correct for perspective acceleration which is induced by the motion along the line of sight." The RVS reveals the velocity of the star along the line of sight of Gaia by measuring the Doppler shift of absorption lines in a high-resolution spectrum.

In order to maintain the fine pointing to focus on stars many light years away, the only moving parts are actuators to align the mirrors and the valves to fire the thrusters. It has no reaction wheels or gyroscopes. The spacecraft subsystems are mounted on a rigid silicon carbide frame, which provides a stable structure that will not expand or contract due to temperature. Attitude control is provided by small cold gas thrusters that can output 1.5 micrograms of nitrogen per second.

The telemetric link with the satellite is about 3 Mbit/s on average, while the total content of the focal plane represents several Gbit/s. Therefore, only a few dozen pixels around each object can be downlinked.

- Mirrors (M)

- Mirrors of telescope 1 (M1, M2 and M3)

- Mirrors of telescope 2 (M'1, M'2 and M'3)

- mirrors M4, M'4, M5, M6 are not shown

- Other components (1–9)

- Optical bench (silicon carbide torus)

- Focal plane cooling radiator

- Focal plane electronics

- Nitrogen tanks

- Diffraction grating spectroscope

- Liquid propellant tanks

- Star trackers

- Telecommunication panel and batteries

- Main propulsion subsystem

- (A) Light path of telescope 1

The design of the Gaia focal plane and instruments. Due to the spacecraft's rotation, images cross the focal plane array right-to-left at 60 arcseconds per second.

- Incoming light from mirror M3

- Incoming light from mirror M'3

- Focal plane, containing the detector for the Astrometric instrument in light blue, Blue Photometer in dark blue, Red Photometer in red, and Radial Velocity Spectrometer in pink

- Mirrors M4 and M'4, which combine the two incoming beams of light

- Mirror M5

- Mirror M6, which illuminates the focal plane

- Optics and diffraction grating for the Radial Velocity Spectrometer (RVS)

- Prisms for the Blue Photometer and Red Photometer (BP and RP)

Measurement principles

Similar to its predecessor Hipparcos, but with a precision one hundred times better, Gaia consists of two telescopes providing two observing directions with a fixed, wide angle of 106.5° between them. The spacecraft rotates continuously around an axis perpendicular to the two telescopes' lines of sight. The spin axis in turn has a slight precession across the sky, while maintaining the same angle to the Sun. By precisely measuring the relative positions of objects from both observing directions, a rigid system of reference is obtained.

The two key telescope properties are:

- 1.45 × 0.5 m primary mirror for each telescope

- 1.0 × 0.5 m focal plane array on which light from both telescopes is projected. This in turn consists of 106 CCDs of 4500 × 1966 pixels each, for a total of 937.8 megapixels (commonly depicted as a gigapixel-class imaging device).

Each celestial object was observed on average about 70 times during the five years of the nominal mission, which has been extended to approximately ten years and will thus obtain twice as many observations. These measurements will help determine the astrometric parameters of stars: two corresponding to the angular position of a given star on the sky, two for the derivatives of the star's position over time (motion) and lastly, the star's parallax from which distance can be calculated. The radial velocity of the brighter stars is measured by an integrated spectrometer observing the Doppler effect. Because of the physical constraints imposed by the Soyuz spacecraft, Gaia's focal arrays could not be equipped with optimal radiation shielding, and ESA expected their performance to suffer somewhat toward the end of the initial five-year mission. Ground tests of the CCDs while they were subjected to radiation provided reassurance that the primary mission's objectives can be met.

An atomic clock on board Gaia plays a crucial role in achieving the mission's primary objectives. Gaia rotates with angular velocity of 60"/sec or 0.6 microarcseconds in 10 nanoseconds. Therefore, in order to meet its positioning goals, Gaia must be able to record the exact time of observation to within nanoseconds. Furthermore, no systematic positioning errors over the rotational period of 6 hours should be introduced by the clock performance. For the timing error to be below 10 nanoseconds over each rotational period, the frequency stability of the on-board clock needs to be better than 10−12. The rubidium atomic clock aboard the Gaia spacecraft has a stability reaching ∼ 10−13 over each rotational period of 21600 seconds.

Gaia's measurements contribute to the creation and maintenance of a high-precision celestial reference frame, the Barycentric Celestial Reference System (BCRS), which is essential for both astronomy and navigation. This reference frame serves as a fundamental grid for positioning celestial objects in the sky, aiding astronomers in various research endeavors. All observations, regardless of the actual positioning of the spacecraft, must be expressed in terms of this reference system. As a fully relativistic model, the influence of the gravitational field of the solar-system must taken into account, including such factors as the gravitational light-bending due to the Sun, the major planets and the Moon.

The expected accuracies of the final catalogue data have been calculated following in-orbit testing, taking into account the issues of stray light, degradation of the optics, and the basic angle instability. The best accuracies for parallax, position and proper motion are obtained for the brighter observed stars, apparent magnitudes 3–12. The standard deviation for these stars is expected to be 6.7 micro-arcseconds or better. For fainter stars, error levels increase, reaching 26.6 micro-arcseconds error in the parallax for 15th-magnitude stars, and several hundred micro-arcseconds for 20th-magnitude stars. For comparison, the best parallax error levels from the new Hipparcos reduction are no better than 100 micro-arcseconds, with typical levels several times larger.

Data processing

The overall data volume that was retrieved from the spacecraft during the nominal five-year mission at a compressed data rate of 1 Mbit/s is approximately 60 TB, amounting to about 200 TB of usable uncompressed data on the ground, stored in an InterSystems Caché database. The responsibility of the data processing, partly funded by ESA, is entrusted to a European consortium, the Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC), which was selected after its proposal to the ESA Announcement of Opportunity released in November 2006. DPAC's funding is provided by the participating countries and has been secured until the production of Gaia's final catalogue.

Gaia sends back data for about eight hours every day at about 5 Mbit/s. ESA's three 35-metre-diameter radio dishes of the ESTRACK network in Cebreros, Spain, Malargüe, Argentina and New Norcia, Australia, receive the data.

Launch and orbit

In October 2013 ESA had to postpone Gaia's original launch date, due to a precautionary replacement of two of Gaia's transponders. These are used to generate timing signals for the downlink of science data. A problem with an identical transponder on a satellite already in orbit motivated their replacement and reverification once incorporated into Gaia. The rescheduled launch window was from 17 December 2013 to 5 January 2014, with Gaia slated for launch on 19 December.

Gaia was successfully launched on 19 December 2013 at 09:12 UTC. About three weeks after launch, on 8 January 2014, it reached its designated orbit around the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrange point (SEL2), about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth.

In 2015, the Pan-STARRS observatory discovered an object orbiting the Earth, which the Minor Planet Center catalogued as object 2015 HP116. It was soon found to be an accidental rediscovery of the Gaia spacecraft and the designation was promptly retracted.

Stray light problem

Shortly after launch, ESA revealed that Gaia was suffering from a stray light problem. The problem was initially thought to be due to ice deposits causing some of the light diffracted around the edges of the sunshield and entering the telescope apertures to be reflected towards the focal plane. The actual source of the stray light was later identified as the fibers of the sunshield, protruding beyond the edges of the shield. This results in a "degradation in science performance [which] will be relatively modest and mostly restricted to the faintest of Gaia's one billion stars." Mitigation schemes are being implemented to improve performance. The degradation is more severe for the RVS spectrograph than for the astrometry measurements, because it spreads the light of the star onto a much larger number of detector pixels which each collect scattered light.

This kind of problem has some historical background. In 1985 on STS-51-F, the Space Shuttle Spacelab-2 mission, another astronomical mission hampered by stray debris was the Infrared Telescope (IRT), in which a piece of mylar insulation broke loose and floated into the line-of-sight of the telescope causing corrupted data. The testing of stray-light and baffles is a noted part of space imaging instruments.

Mission progress

The testing and calibration phase, which started while Gaia was en route to SEL2 point, continued until the end of July 2014, three months behind schedule due to unforeseen issues with stray light entering the detector. After the six-month commissioning period, the satellite started its nominal five-year period of scientific operations on 25 July 2014 using a special scanning mode that intensively scanned the region near the ecliptic poles; on 21 August 2014 Gaia began using its normal scanning mode which provides more uniform coverage.

Although it was originally planned to limit Gaia's observations to stars fainter than magnitude 5.7, tests carried out during the commissioning phase indicated that Gaia could autonomously identify stars as bright as magnitude 3. When Gaia entered regular scientific operations in July 2014, it was configured to routinely process stars in the magnitude range 3 – 20. Beyond that limit, special procedures are used to download raw scanning data for the remaining 230 stars brighter than magnitude 3; methods to reduce and analyse these data are being developed; and it is expected that there will be "complete sky coverage at the bright end" with standard errors of "a few dozen μas".

On 12 September 2014, Gaia discovered its first supernova in another galaxy. On 3 July 2015, a map of the Milky Way by star density was released, based on data from the spacecraft. As of August 2016, "more than 50 billion focal plane transits, 110 billion photometric observations and 9.4 billion spectroscopic observations have been successfully processed."

In 2018 the Gaia mission was extended to 2020. In 2020 the Gaia mission was further extended through 2022, with an additional "indicative extension" extending through 2025. The limiting factor to further mission extensions is the supply of nitrogen for the cold gas thrusters of the micro-propulsion system. The amount of dinitrogen tetroxide (NTO) and monomethylhydrazine (MMH) for the chemical propulsion subsystem on board might be enough to stabilize the spacecraft at L2 for several decades. Without the cold gas the space craft can no longer be pointed on a microarcsecond scale.

In March 2023, the Gaia mission was extended through the second quarter of 2025, when it is expected that the spacecraft will run out of cold gas propellant. It will then enter a post-operations phase that is expected to be completed by the end of 2030.

Data releases

Several Gaia catalogues are released over the years each time with increasing amounts of information and better astrometry; the early releases also miss some stars, especially fainter stars located in dense star fields and members of close binary pairs. The first data release, Gaia DR1, based on 14 months of observation was on 14 September 2016. The data release includes "positions and ... magnitudes for 1.1 billion stars using only Gaia data; positions, parallaxes and proper motions for more than 2 million stars" based on a combination of Gaia and Tycho-2 data for those objects in both catalogues; "light curves and characteristics for about 3,000 variable stars; and positions and magnitudes for more than 2000 ... extragalactic sources used to define the celestial reference frame".

The second data release (DR2), which occurred on 25 April 2018, is based on 22 months of observations made between 25 July 2014 and 23 May 2016. It includes positions, parallaxes and proper motions for about 1.3 billion stars and positions of an additional 300 million stars in the magnitude range g = 3–20, red and blue photometric data for about 1.1 billion stars and single colour photometry for an additional 400 million stars, and median radial velocities for about 7 million stars between magnitude 4 and 13. It also contains data for over 14,000 selected Solar System objects.

Due to uncertainties in the data pipeline, the third data release, based on 34 months of observations, has been split into two parts so that data that was ready first, was released first. The first part, EDR3 ("Early Data Release 3"), consisting of improved positions, parallaxes and proper motions, was released on 3 December 2020. The coordinates in EDR3 use a new version of the Gaia celestial reference frame (Gaia–CRF3), based on observations of 1,614,173 extragalactic sources, 2,269 of which were common to radio sources in the third revision of the International Celestial Reference Frame (ICRF3). Included is the Gaia Catalogue of Nearby Stars (GCNS), containing 331,312 stars within (nominally) 100 parsecs (330 light-years).

The full DR3, published on 13 June 2022, includes the EDR3 data plus Solar System data; variability information; results for non-single stars, for quasars, and for extended objects; astrophysical parameters; and a special data set, the Gaia Andromeda Photometric Survey (GAPS). The final Gaia catalogue is expected to be released three years after the end of the Gaia mission.

Future releases

The full data release for the five-year nominal mission, DR4, will include full astrometric, photometric and radial-velocity catalogues, variable-star and non-single-star solutions, source classifications plus multiple astrophysical parameters for stars, unresolved binaries, galaxies and quasars, an exo-planet list and epoch and transit data for all sources. Additional release(s) will take place depending on mission extensions. Most measurements in DR4 are expected to be 1.7 times more precise than DR2; proper motions will be 4.5 times more precise.

The last catalogue, DR5, will use and publish the full ten years of data. It will be 1.4 times more precise than DR4, while proper motions will be 2.8 times more precise than DR4. It will be published not earlier than three years after the end of the mission. All data of all catalogues will be available in an online data base that is free to use.

An outreach application, Gaia Sky, has been developed to explore the galaxy in three dimensions using Gaia data.

Significant results

In July 2017 the Gaia-ESO Survey reported using the data to find double-, triple-, and quadruple- stars. Using advanced techniques they identified 342 binary candidates, 11 triple candidates, and 1 quadruple candidate. Nine of these had been identified by other means, thus confirming that the technique can correctly identify multiple star systems. The possible quadruple star system is HD 74438, which was, in a paper published in 2022, identified as a possible progenitor of a sub-Chandrasekhar Type Ia supernovae.

In November 2017, scientists led by Davide Massari of the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Netherlands released a paper describing the characterization of proper motion (3D) within the Sculptor dwarf galaxy, and of that galaxy's trajectory through space and with respect to the Milky Way, using data from Gaia and the Hubble Space Telescope. Massari said, "With the precision achieved we can measure the yearly motion of a star on the sky which corresponds to less than the size of a pinhead on the Moon as seen from Earth." The data showed that Sculptor orbits the Milky Way in a highly elliptical orbit; it is currently near its closest approach at a distance of about 83.4 kiloparsecs (272,000 ly), but the orbit can take it out to around 222 kiloparsecs (720,000 ly) distant.

In October 2018, Leiden University astronomers were able to determine the orbits of 20 hypervelocity stars from the DR2 dataset. Expecting to find a single star exiting the Milky Way, they instead found seven. More surprisingly, the team found that 13 hypervelocity stars were instead approaching the Milky Way, possibly originating from as-of-yet unknown extragalactic sources. Alternatively, they could be halo stars to this galaxy, and further spectroscopic studies will help determine which scenario is more likely. Independent measurements have demonstrated that the greatest Gaia radial velocity among the hypervelocity stars is contaminated by light from nearby bright stars in a crowded field and cast doubt on the high Gaia radial velocities of other hypervelocity stars.

In late October 2018, the galactic population Gaia-Enceladus, the remains of a major merger with the defunct Enceladus dwarf, was discovered. This system is associated with at least 13 globular clusters, and the creation of the Thick Disk of the Milky Way. It represents a significant merger about 10 billion years ago in the Milky Way Galaxy.

In November 2018, the galaxy Antlia 2 was discovered. It is similar in size to the Large Magellanic Cloud, despite being 10,000 times fainter. Antlia 2 has the lowest surface brightness of any galaxy discovered.

In December 2019 the star cluster Price-Whelan 1 was discovered. The cluster belongs to the Magellanic Clouds and is located in the leading arm of these Dwarf Galaxies. The discovery suggests that the stream of gas extending from the Magellanic Clouds to the Milky Way is about half as far from the Milky Way as previously thought.

The Radcliffe wave was discovered in data measured by Gaia, published in January 2020.

In November 2020, Gaia measured the acceleration of the solar system towards the galactic center as 0.23 nanometers/s2.

In March 2021, the European Space Agency announced that Gaia had identified a transiting exoplanet for the first time. The planet was discovered orbiting solar-type star Gaia EDR3 3026325426682637824. Following its initial discovery, the PEPSI spectrograph from the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) in Arizona was used to confirm the discovery and categorise it as a Jovian planet, a gas planet composed of hydrogen and helium gas. In May 2022, the confirmation of this exoplanet, designated Gaia-1b, was formally published, along with a second planet, Gaia-2b.

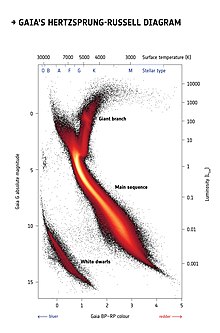

Based on its data, Gaia's Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HR diagram) is one of the most accurate ones ever produced of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Analysis of Gaia DR3 data in 2022 revealed a Sun-like star with the identifier Gaia DR3 4373465352415301632 orbiting a black hole, dubbed Gaia BH1. At a distance of roughly 1,600 light-years (490 pc), it is the closest known black hole to Earth. Another system with a red giant orbiting a black hole, Gaia BH2, was also discovered.

In September 2023, radial velocity observations were used to confirm an exoplanet orbiting the star HIP 66074 that was first detected in Gaia DR3 astrometry data. This planet, known as HIP 66074 b or Gaia-3b, is the third Gaia exoplanet discovery to be confirmed and the first such discovery made using astrometry. In addition, another exoplanet was discovered from a gravitational microlensing event observed by Gaia, Gaia22dkv. The host star is brighter than that of any exoplanet previously detected by microlensing, potentially making the planet detectable by radial velocity as well.