Palestine | |

|---|---|

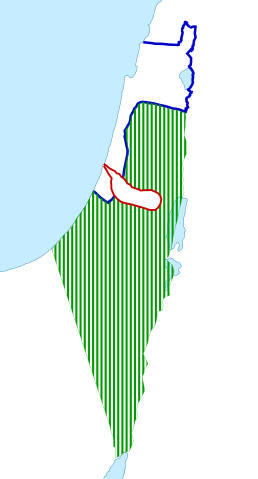

Boundary of Syria Palaestina Boundary between Palaestina Prima (later Jund Filastin) and Palaestina Secunda (later Jund al-Urdunn) Borders of Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and 1948 | |

| Languages | Arabic, Hebrew |

| Ethnic groups | Arabs, Jews |

| Countries | |

Palestine is a geographical region in West Asia. Situated in the Southern Levant, it is usually considered to include Israel and the State of Palestine, though some definitions also include parts of northwestern Jordan. Other historical names for the region include Canaan, the Promised Land, the Land of Israel, or the Holy Land.

The first written records referring to Palestine emerged in the 12th-century BCE Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt, which used the term Peleset for a neighboring people or land. In the 8th century BCE, the Assyrians referred to a region as Palashtu or Pilistu. In the Hellenistic period, these names were carried over into Greek, appearing in the Histories of Herodotus in 5th century BCE as Palaistine. The Roman Empire conquered the region and in 6 CE established the province known as Judaea, then in 132 CE in the period of the Bar Kokhba revolt the province was expanded and renamed Syria Palaestina. In 390, during the Byzantine period, the region was split into the provinces of Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda, and Palaestina Tertia. Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s, the military district of Jund Filastin was established. While Palestine's boundaries have changed throughout history, it has generally comprised the southern portion of regions such as Syria or the Levant. It also conceptually overlaps with several terms of Judeo-Christian tradition, including Canaan, the Promised Land, the Land of Israel, and the Holy Land.

As the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. In the Bronze Age, it was inhabited by the Canaanites; the Iron Age saw the emergence of Israel and Judah, two related kingdoms inhabited by the Israelites. It has since come under the sway of various empires, including the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the Neo-Babylonian Empire, and the Achaemenid Empire. Revolts by the region's Jews against Hellenistic rule brought a brief period of regional independence under the Hasmonean dynasty, which ended with its gradual incorporation into the Roman Empire (later the Byzantine Empire).

In the 7th century, Palestine was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate, ending Byzantine rule in the region; Rashidun rule was succeeded by the Umayyad Caliphate, the Abbasid Caliphate, and the Fatimid Caliphate. Following the collapse of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which had been established through the Crusades, the population of Palestine became predominantly Muslim. In the 13th century, it became part of the Mamluk Sultanate, and after 1516, part of the Ottoman Empire. During World War I, it was captured by the United Kingdom as part of the Sinai and Palestine campaign. Between 1919 and 1922, the League of Nations created the Mandate for Palestine, which directed the region to be under British administration as Mandatory Palestine. Tensions between Jews and Arabs escalated into the 1947–1949 Palestine war, which ended with the remaining territory of the former British Mandate post the creation of Transjordan in 1946 divided between Israel vis-à-vis Jordan (in the West Bank) and Egypt (in the Gaza Strip); later developments in the Arab–Israeli conflict culminated in Israel's occupation of both territories, which has been among the core issues of the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Etymology

Modern archaeology has identified 12 ancient inscriptions from Egyptian and Assyrian records recording likely cognates of Hebrew Pelesheth. The term "Peleset" (transliterated from hieroglyphs as P-r-s-t) is found in five inscriptions referring to a neighboring people or land starting from c. 1150 BCE during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt. The first known mention is at the temple at Medinet Habu which refers to the Peleset among those who fought with Egypt in Ramesses III's reign, and the last known is 300 years later on Padiiset's Statue. Seven known Assyrian inscriptions refer to the region of "Palashtu" or "Pilistu", beginning with Adad-nirari III in the Nimrud Slab in c. 800 BCE through to a treaty made by Esarhaddon more than a century later. Neither the Egyptian nor the Assyrian sources provided clear regional boundaries for the term.

The first clear use of the term Palestine to refer to the entire area between Phoenicia and Egypt was in 5th century BCE ancient Greece, when Herodotus wrote of a "district of Syria, called Palaistinê" (Ancient Greek: Συρίη ἡ Παλαιστίνη καλεομένη) in The Histories, which included the Judean mountains and the Jordan Rift Valley. Approximately a century later, Aristotle used a similar definition for the region in Meteorology, in which he included the Dead Sea. Later Greek writers such as Polemon and Pausanias also used the term to refer to the same region, which was followed by Roman writers such as Ovid, Tibullus, Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Dio Chrysostom, Statius, Plutarch as well as Romano-Jewish writers Philo of Alexandria and Josephus. The term was first used to denote an official province in c. 135 CE, when the Roman authorities, following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, renamed the province of Judaea "Syria Palaestina". There is circumstantial evidence linking Hadrian with the name change, but the precise date is not certain.

The term is generally accepted to be a cognate of the biblical name Peleshet (פלשת Pəlésheth, usually transliterated as Philistia). The term and its derivates are used more than 250 times in Masoretic-derived versions of the Hebrew Bible, of which 10 uses are in the Torah, with undefined boundaries, and almost 200 of the remaining references are in the Book of Judges and the Books of Samuel. The term is rarely used in the Septuagint, which used a transliteration Land of Phylistieim (Γῆ τῶν Φυλιστιείμ), different from the contemporary Greek place name Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη). It also theorized to be the portmanteau of the Greek word for the Philistines and palaistês, which means "wrestler/rival/adversary". This aligns with the Greek practice of punning place names since the latter is also the etymological meaning for Israel.

The Septuagint instead used the term "allophuloi" (άλλόφυλοι, "other nations") throughout the Books of Judges and Samuel, such that the term "Philistines" has been interpreted to mean "non-Israelites of the Promised Land" when used in the context of Samson, Saul and David, and Rabbinic sources explain that these peoples were different from the Philistines of the Book of Genesis.

During the Byzantine period, the region of Palestine within Syria Palaestina was subdivided into Palaestina Prima and Secunda, and an area of land including the Negev and Sinai became Palaestina Salutaris. Following the Muslim conquest, place names that were in use by the Byzantine administration generally continued to be used in Arabic. The use of the name "Palestine" became common in Early Modern English, was used in English and Arabic during the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem and was revived as an official place name with the British Mandate for Palestine.

Some other terms that have been used to refer to all or part of this land include Canaan, Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael or Ha'aretz), the Promised Land, Greater Syria, the Holy Land, Iudaea Province, Judea, Coele-Syria, "Israel HaShlema", Kingdom of Israel, Kingdom of Jerusalem, Zion, Retenu (Ancient Egyptian), Southern Syria, Southern Levant and Syria Palaestina.

History

Overview

Situated at a strategic location between Egypt, Syria and Arabia, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, the region has a long and tumultuous history as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. The region has been controlled by numerous peoples, including ancient Egyptians, Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Achaemenids, ancient Greeks, Romans, Parthians, Sasanians, Byzantines, the Arab Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Mongols, Ottomans, the British, and modern Israelis and Palestinians.

Ancient period

The region was among the earliest in the world to see human habitation, agricultural communities and civilization. During the Bronze Age, independent Canaanite city-states were established, and were influenced by the surrounding civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Minoan Crete, and Syria. Between 1550 and 1400 BCE, the Canaanite cities became vassals to the Egyptian New Kingdom who held power until the 1178 BCE Battle of Djahy (Canaan) during the wider Bronze Age collapse. The Israelites emerged from a dramatic social transformation that took place in the people of the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE, with no signs of violent invasion or even of peaceful infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group from elsewhere. During the Iron Age, the Israelites established two related kingdoms, Israel and Judah. The Kingdom of Israel emerged as an important local power by the 10th century BCE before falling to the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE. Israel's southern neighbor, the Kingdom of Judah, emerged in the 8th or 9th century BCE and later became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian and then the Neo-Babylonian Empire before a revolt against the latter led to its destruction in 586 BCE. The region became part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from c. 740 BCE, which was itself replaced by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in c. 627 BCE.

In 587/6 BCE, Jerusalem was besieged and destroyed by the second Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar II, who subsequently exiled the Judeans to Babylon. The Kingdom of Judah was then annexed as a Babylonian province. The Philistines were also exiled. The defeat of Judah was recorded by the Babylonians.

In 539 BCE, the Babylonian empire was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Hebrew Bible and implications from the Cyrus Cylinder, the exiled Jews were eventually allowed to return to Jerusalem. The returned population in Judah were allowed to self-rule under Persian governance, and some parts of the fallen kingdom became a Persian province known as Yehud. Except Yehud, at least another four Persian provinces existed in the region: Samaria, Gaza, Ashdod, and Ascalon, in addition to the Phoenician city states in the north and the Arabian tribes in the south. During the same period, the Edomites migrated from Transjordan to the southern parts of Judea, which became known as Idumaea. The Qedarites were the dominant Arab tribe; their territory ran from the Hejaz in the south to the Negev in the north through the period of Persian and Hellenistic dominion.

Classical antiquity

In the 330s BCE, Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the region, which changed hands several times during the wars of the Diadochi and later Syrian Wars. It ultimately fell to the Seleucid Empire between 219 and 200 BCE. During that period, the region became heavily hellenized, building tensions between Greeks and locals. In 167 BCE, the Maccabean Revolt erupted, leading to the establishment of an independent Hasmonean Kingdom in Judea. From 110 BCE, the Hasmoneans extended their authority over much of Palestine, including Samaria, Galilee, Iturea, Perea, and Idumea. The Jewish control over the wider region resulted in it also becoming known as Judaea, a term that had previously only referred to the smaller region of the Judaean Mountains. During the same period, the Edomites were converted to Judaism.

Between 73 and 63 BCE, the Roman Republic extended its influence into the region in the Third Mithridatic War. Pompey conquered Judea in 63 BCE, splitting the former Hasmonean Kingdom into five districts. In around 40 BCE, the Parthians conquered Palestine, deposed the Roman ally Hyrcanus II, and installed a puppet ruler of the Hasmonean line known as Antigonus II. By 37 BCE, the Parthians withdrew from Palestine.

Palestine is generally considered the "Cradle of Christianity". Christianity, a religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, arose as a messianic sect from within Second Temple Judaism. The three-year Ministry of Jesus, culminating in his crucifixion, is estimated to have occurred from 28 to 30 CE, although the historicity of Jesus is disputed by a minority of scholars.

In the first and second centuries CE, the province of Judea became the site of two large-scale Jewish revolts against Rome. During the First Jewish-Roman War, which lasted from 66 to 73 CE, the Romans razed Jerusalem and destroyed the Second Temple. In Masada, Jewish zealots preferred to commit suicide than endure Roman captivity. In 132 CE, another Jewish rebellion erupted. The Bar Kokhba revolt took three years to put down, incurred massive costs on both the Romans and the Jews, and desolated much of Judea. The center of Jewish life in Palestine moved to the Galile During or after the revolt, Hadrian joined the province of Iudaea with Galilee and the Paralia to form the new province of Syria Palaestina, and Jerusalem was renamed "Aelia Capitolina". Some scholars view these actions as an attempt to disconnect the Jewish people from their homeland, but this theory is debated.

Between 259 and 272, the region fell under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire. Following the victory of Christian emperor Constantine in the Civil wars of the Tetrarchy, the Christianization of the Roman Empire began, and in 326, Constantine's mother Saint Helena visited Jerusalem and began the construction of churches and shrines. Palestine became a center of Christianity, attracting numerous monks and religious scholars. The Samaritan Revolts during this period caused their near extinction. In 614 CE, Palestine was annexed by another Persian dynasty; the Sassanids, until returning to Byzantine control in 628 CE.

Early Muslim period

Palestine was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate, beginning in 634 CE. In 636, the Battle of Yarmouk during the Muslim conquest of the Levant marked the start of Muslim hegemony over the region, which became known as the military district of Jund Filastin within the province of Bilâd al-Shâm (Greater Syria). In 661, with the Assassination of Ali, Muawiyah I became the Caliph of the Islamic world after being crowned in Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock, completed in 691, was the world's first great work of Islamic architecture.

The majority of the population was Christian and was to remain so until the conquest of Saladin in 1187. The Muslim conquest apparently had little impact on social and administrative continuities for several decades. The word 'Arab' at the time referred predominantly to Bedouin nomads, though Arab settlement is attested in the Judean highlands and near Jerusalem by the 5th century, and some tribes had converted to Christianity. The local population engaged in farming, which was considered demeaning, and were called Nabaț, referring to Aramaic-speaking villagers. A ḥadīth, brought in the name of a Muslim freedman who settled in Palestine, ordered the Muslim Arabs not to settle in the villages, "for he who abides in villages it is as if he abides in graves".

The Umayyads, who had spurred a strong economic resurgence in the area, were replaced by the Abbasids in 750. Ramla became the administrative centre for the following centuries, while Tiberias became a thriving centre of Muslim scholarship. From 878, Palestine was ruled from Egypt by semi-autonomous rulers for almost a century, beginning with the Turkish freeman Ahmad ibn Tulun, for whom both Jews and Christians prayed when he lay dying and ending with the Ikhshidid rulers. Reverence for Jerusalem increased during this period, with many of the Egyptian rulers choosing to be buried there. However, the later period became characterized by persecution of Christians as the threat from Byzantium grew. The Fatimids, with a predominantly Berber army, conquered the region in 970, a date that marks the beginning of a period of unceasing warfare between numerous enemies, which destroyed Palestine, and in particular, devastating its Jewish population. Between 1071 and 1073, Palestine was captured by the Great Seljuq Empire, only to be recaptured by the Fatimids in 1098.

Crusader/Ayyubid period

The Fatimids again lost the region to the Crusaders in 1099. The Crusaders set up the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291). Their control of Jerusalem and most of Palestine lasted almost a century until their defeat by Saladin's forces in 1187, after which most of Palestine was controlled by the Ayyubids, except for the years 1229–1244 when Jerusalem and other areas were retaken by the Second Kingdom of Jerusalem, by then ruled from Acre (1191–1291), but, despite seven further crusades, the Franks were no longer a significant power in the region. The Fourth Crusade, which did not reach Palestine, led directly to the decline of the Byzantine Empire, dramatically reducing Christian influence throughout the region.

Mamluk period

The Mamluk Sultanate was created in Egypt as an indirect result of the Seventh Crusade. The Mongol Empire reached Palestine for the first time in 1260, beginning with the Mongol raids into Palestine under Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa, and reaching an apex at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut, where they were pushed back by the Mamluks.

Ottoman period

In 1486, hostilities broke out between the Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire in a battle for control over western Asia, and the Ottomans conquered Palestine in 1516. Between the mid-16th and 17th centuries, a close-knit alliance of three local dynasties, the Ridwans of Gaza, the Turabays of al-Lajjun and the Farrukhs of Nablus, governed Palestine on behalf of the Porte (imperial Ottoman government).

In the 18th century, the Zaydani clan under the leadership of Zahir al-Umar ruled large parts of Palestine autonomously until the Ottomans were able to defeat them in their Galilee strongholds in 1775–76. Zahir had turned the port city of Acre into a major regional power, partly fueled by his monopolization of the cotton and olive oil trade from Palestine to Europe. Acre's regional dominance was further elevated under Zahir's successor Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar at the expense of Damascus.

In 1830, on the eve of Muhammad Ali's invasion, the Porte transferred control of the sanjaks of Jerusalem and Nablus to Abdullah Pasha, the governor of Acre. According to Silverburg, in regional and cultural terms this move was important for creating an Arab Palestine detached from greater Syria (bilad al-Sham). According to Pappe, it was an attempt to reinforce the Syrian front in face of Muhammad Ali's invasion. Two years later, Palestine was conquered by Muhammad Ali's Egypt, but Egyptian rule was challenged in 1834 by a countrywide popular uprising against conscription and other measures considered intrusive by the population. Its suppression devastated many of Palestine's villages and major towns.

In 1840, Britain intervened and returned control of the Levant to the Ottomans in return for further capitulations. The death of Aqil Agha marked the last local challenge to Ottoman centralization in Palestine, and beginning in the 1860s, Palestine underwent an acceleration in its socio-economic development, due to its incorporation into the global, and particularly European, economic pattern of growth. The beneficiaries of this process were Arabic-speaking Muslims and Christians who emerged as a new layer within the Arab elite. From 1880 large-scale Jewish immigration began, almost entirely from Europe, based on an explicitly Zionist ideology. There was also a revival of the Hebrew language and culture.

Christian Zionism in the United Kingdom preceded its spread within the Jewish community. The government of Great Britain publicly supported it during World War I with the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

British Mandate period

The British began their Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1915. The war reached southern Palestine in 1917, progressing to Gaza and around Jerusalem by the end of the year. The British secured Jerusalem in December 1917. They moved into the Jordan valley in 1918 and a campaign by the Entente into northern Palestine led to victory at Megiddo in September.

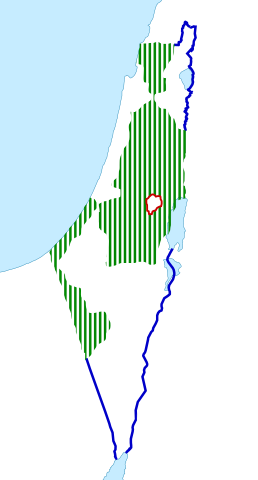

The British were formally awarded the mandate to govern the region in 1922. The Arab Palestinians rioted in 1920, 1921, 1929, and revolted in 1936. In 1947, following World War II and The Holocaust, the British Government announced its desire to terminate the Mandate, and the United Nations General Assembly adopted in November 1947 a Resolution 181(II) recommending partition into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem. A civil war began immediately after the Resolution's adoption. The State of Israel was declared in May 1948.

Arab–Israeli conflict

In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Israel captured and incorporated a further 26% of the Mandate territory, Jordan captured the regions of Judea and Samaria, renaming it the "West Bank", while the Gaza Strip was captured by Egypt. Following the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight, also known as al-Nakba, the 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes were not allowed to return following the Lausanne Conference of 1949.

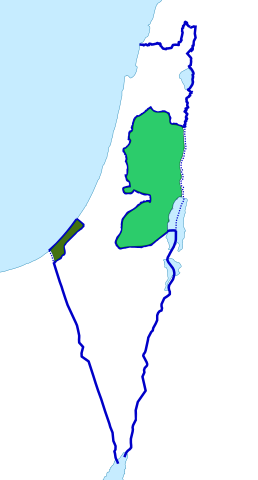

In the course of the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured the rest of Mandate Palestine from Jordan and Egypt, and began a policy of establishing Jewish settlements in those territories. From 1987 to 1993, the First Palestinian Intifada against Israel took place, which included the Declaration of the State of Palestine in 1988 and ended with the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords and the creation of the Palestinian National Authority.

In 2000, the Second Intifada (also called al-Aqsa Intifada) began, and Israel built a separation barrier. In the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza, Israel withdrew all settlers and military presence from the Gaza Strip, but maintained military control of numerous aspects of the territory including its borders, air space and coast. Israel's ongoing military occupation of the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and East Jerusalem continues to be the world's longest military occupation in modern times.

In 2008 Palestinian hikaye was inscribed to UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage; the first of four listings reflecting the significance of Palestinian culture globally.

In November 2012, the status of Palestinian delegation in the United Nations was upgraded to non-member observer state as the State of Palestine.

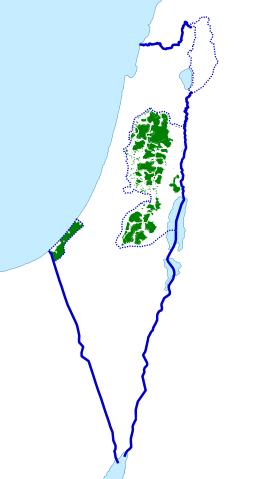

Boundaries

Pre-modern period

The boundaries of Palestine have varied throughout history. The Jordan Rift Valley (comprising Wadi Arabah, the Dead Sea and River Jordan) has at times formed a political and administrative frontier, even within empires that have controlled both territories. At other times, such as during certain periods during the Hasmonean and Crusader states for example, as well as during the biblical period, territories on both sides of the river formed part of the same administrative unit. During the Arab Caliphate period, parts of southern Lebanon and the northern highland areas of Palestine and Jordan were administered as Jund al-Urdun, while the southern parts of the latter two formed part of Jund Dimashq, which during the 9th century was attached to the administrative unit of Jund Filastin.

The boundaries of the area and the ethnic nature of the people referred to by Herodotus in the 5th century BCE as Palaestina vary according to context. Sometimes, he uses it to refer to the coast north of Mount Carmel. Elsewhere, distinguishing the Syrians in Palestine from the Phoenicians, he refers to their land as extending down all the coast from Phoenicia to Egypt. Pliny, writing in Latin in the 1st century CE, describes a region of Syria that was "formerly called Palaestina" among the areas of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Since the Byzantine Period, the Byzantine borders of Palaestina (I and II, also known as Palaestina Prima, "First Palestine", and Palaestina Secunda, "Second Palestine"), have served as a name for the geographic area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Under Arab rule, Filastin (or Jund Filastin) was used administratively to refer to what was under the Byzantines Palaestina Secunda (comprising Judaea and Samaria), while Palaestina Prima (comprising the Galilee region) was renamed Urdunn ("Jordan" or Jund al-Urdunn).

Modern period

Nineteenth-century sources refer to Palestine as extending from the sea to the caravan route, presumably the Hejaz-Damascus route east of the Jordan River valley. Others refer to it as extending from the sea to the desert. Prior to the Allied Powers victory in World War I and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, which created the British mandate in the Levant, most of the northern area of what is today Jordan formed part of the Ottoman Vilayet of Damascus (Syria), while the southern part of Jordan was part of the Vilayet of Hejaz. What later became Mandatory Palestine was in late Ottoman times divided between the Vilayet of Beirut (Lebanon) and the Sanjak of Jerusalem. The Zionist Organization provided its definition of the boundaries of Palestine in a statement to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

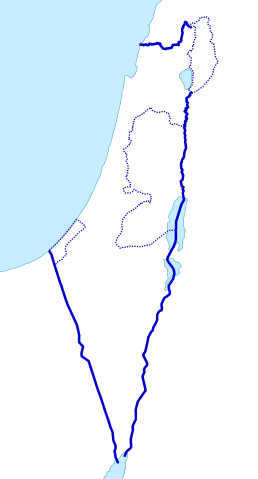

The British administered Mandatory Palestine after World War I, having promised to establish a homeland for the Jewish people. The modern definition of the region follows the boundaries of that entity, which were fixed in the North and East in 1920–23 by the British Mandate for Palestine (including the Transjordan memorandum) and the Paulet–Newcombe Agreement, and on the South by following the 1906 Turco-Egyptian boundary agreement.

Current usage

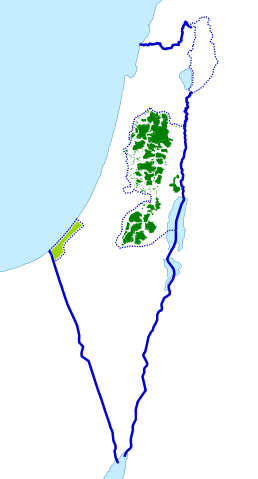

The region of Palestine is the eponym for the Palestinian people and the culture of Palestine, both of which are defined as relating to the whole historical region, usually defined as the localities within the border of Mandatory Palestine. The 1968 Palestinian National Covenant described Palestine as the "homeland of the Arab Palestinian people", with "the boundaries it had during the British Mandate".

However, since the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence, the term State of Palestine refers only to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This discrepancy was described by the Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas as a negotiated concession in a September 2011 speech to the United Nations: "... we agreed to establish the State of Palestine on only 22% of the territory of historical Palestine – on all the Palestinian Territory occupied by Israel in 1967."

The term Palestine is also sometimes used in a limited sense to refer to the parts of the Palestinian territories currently under the administrative control of the Palestinian National Authority, a quasi-governmental entity which governs parts of the State of Palestine under the terms of the Oslo Accords.

Administration

Demographics

Early demographics

Estimating the population of Palestine in antiquity relies on two methods – censuses and writings made at the times, and the scientific method based on excavations and statistical methods that consider the number of settlements at the particular age, area of each settlement, density factor for each settlement.

The Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century CE saw a major shift in the population of Palestine. The sheer scale and scope of the overall destruction has been described by Dio Cassius in his Roman History, where he notes that Roman war operations in the country had left some 580,000 Jews dead, with many more dying of hunger and disease, while 50 of their most important outposts and 985 of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. "Thus," writes Dio Cassius, "nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate."

According to Israeli archaeologists Magen Broshi and Yigal Shiloh, the population of ancient Palestine did not exceed one million. By 300 CE, Christianity had spread so significantly that Jews comprised only a quarter of the population.

Late Ottoman and British Mandate periods

In a study of Ottoman registers of the early Ottoman rule of Palestine, Bernard Lewis reports:

[T]he first half century of Ottoman rule brought a sharp increase in population. The towns grew rapidly, villages became larger and more numerous, and there was an extensive development of agriculture, industry, and trade. The two last were certainly helped to no small extent by the influx of Spanish and other Western Jews.

From the mass of detail in the registers, it is possible to extract something like a general picture of the economic life of the country in that period. Out of a total population of about 300,000 souls, between a fifth and a quarter lived in the six towns of Jerusalem, Gaza, Safed, Nablus, Ramle, and Hebron. The remainder consisted mainly of peasants, living in villages of varying size, and engaged in agriculture. Their main food-crops were wheat and barley in that order, supplemented by leguminous pulses, olives, fruit, and vegetables. In and around most of the towns there was a considerable number of vineyards, orchards, and vegetable gardens.

According to Alexander Scholch, the population of Palestine in 1850 was about 350,000 inhabitants, 30% of whom lived in 13 towns; roughly 85% were Muslims, 11% were Christians and 4% Jews.

According to Ottoman statistics studied by Justin McCarthy, the population of Palestine in the early 19th century was 350,000, in 1860 it was 411,000 and in 1900 about 600,000 of whom 94% were Arabs. In 1914 Palestine had a population of 657,000 Muslim Arabs, 81,000 Christian Arabs, and 59,000 Jews. McCarthy estimates the non-Jewish population of Palestine at 452,789 in 1882; 737,389 in 1914; 725,507 in 1922; 880,746 in 1931; and 1,339,763 in 1946.

In 1920, the League of Nations' Interim Report on the Civil Administration of Palestine described the 700,000 people living in Palestine as follows:

Of these, 235,000 live in the larger towns, 465,000 in the smaller towns and villages. Four-fifths of the whole population are Moslems. A small proportion of these are Bedouin Arabs; the remainder, although they speak Arabic and are termed Arabs, are largely of mixed race. Some 77,000 of the population are Christians, in large majority belonging to the Orthodox Church, and speaking Arabic. The minority are members of the Latin or of the Uniate Greek Catholic Church, or—a small number—are Protestants. The Jewish element of the population numbers 76,000. Almost all have entered Palestine during the last 40 years. Prior to 1850, there were in the country only a handful of Jews. In the following 30 years, a few hundreds came to Palestine. Most of them were animated by religious motives; they came to pray and to die in the Holy Land, and to be buried in its soil. After the persecutions in Russia forty years ago, the movement of the Jews to Palestine assumed larger proportions.

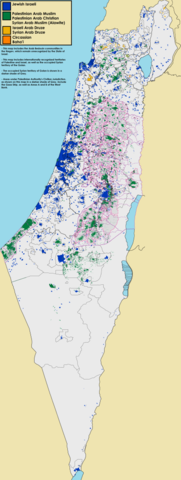

Current demographics

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, as of 2015, the total population of Israel was 8.5 million people, of which 75% were Jews, 21% Arabs, and 4% "others". Of the Jewish group, 76% were Sabras (born in Israel); the rest were olim (immigrants)—16% from Europe, the former Soviet republics, and the Americas, and 8% from Asia and Africa, including the Arab countries.

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics evaluations, in 2015 the Palestinian population of the West Bank was approximately 2.9 million and that of the Gaza Strip was 1.8 million. Gaza's population is expected to increase to 2.1 million people in 2020, leading to a density of more than 5,800 people per square kilometre.

Both Israeli and Palestinian statistics include Arab residents of East Jerusalem in their reports. According to these estimates the total population in the region of Palestine, as defined as Israel and the Palestinian territories, stands approximately 12.8 million.

Flora and fauna

Flora distribution

The World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions is widely used in recording the distribution of plants. The scheme uses the code "PAL" to refer to the region of Palestine – a Level 3 area. The WGSRPD's Palestine is further divided into Israel (PAL-IS), including the Palestinian territories, and Jordan (PAL-JO), so is larger than some other definitions of "Palestine".