Nitrogen fixation is essential to life because fixed inorganic nitrogen compounds are required for the biosynthesis of all nitrogen-containing organic compounds, such as amino acids and proteins, nucleoside triphosphates and nucleic acids. As part of the nitrogen cycle, it is essential for agriculture and the manufacture of fertilizer. It is also, indirectly, relevant to the manufacture of all chemical compounds that contain nitrogen, which includes explosives, most pharmaceuticals, and dyes.

Nitrogen fixation is carried out naturally in the soil by a wide range of microorganisms termed diazotrophs that include bacteria such as Azotobacter, and archaea. Some nitrogen-fixing bacteria have symbiotic relationships with some plant groups, especially legumes. Looser non-symbiotic relationships between diazotrophs and plants are often referred to as associative, as seen in nitrogen fixation on rice roots. Nitrogen fixation also occurs between some termites and fungi. It also occurs naturally in the air by means of NOx production by lightning.

All biological nitrogen fixation is effected by enzymes called nitrogenases. These enzymes contain iron, often with a second metal, usually molybdenum but sometimes vanadium.

Non-biological natural nitrogen fixation

Lightning heats the air around it breaking the bonds of N2 starting the formation of nitrous acid.

Nitrogen can be fixed by lightning converting nitrogen and oxygen into NO

x (nitrogen oxides). NO

x may react with water to make nitrous acid or nitric acid, which seeps into the soil, where it makes nitrate, which is of use to growing plants. Nitrogen in the atmosphere is highly stable and nonreactive due to there being a triple bond between atoms in the N2 molecule. Lightning produces enough energy and heat to break this bond allowing the nitrogen atoms to react with oxygen forming NOx. This itself cannot be used by plants, but as this molecule cools it reacts with more oxygen to form NO2. This molecule in turn reacts with water to produce HNO3 (nitric acid) which is usable by plants.

x (nitrogen oxides). NO

x may react with water to make nitrous acid or nitric acid, which seeps into the soil, where it makes nitrate, which is of use to growing plants. Nitrogen in the atmosphere is highly stable and nonreactive due to there being a triple bond between atoms in the N2 molecule. Lightning produces enough energy and heat to break this bond allowing the nitrogen atoms to react with oxygen forming NOx. This itself cannot be used by plants, but as this molecule cools it reacts with more oxygen to form NO2. This molecule in turn reacts with water to produce HNO3 (nitric acid) which is usable by plants.

Biological nitrogen fixation

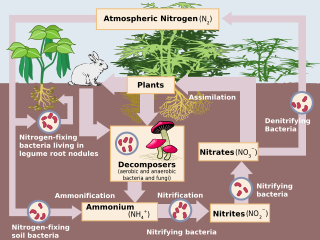

Schematic representation of the nitrogen cycle. Abiotic nitrogen fixation has been omitted.

Biological nitrogen fixation was discovered by the German agronomist Hermann Hellriegel and Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck. Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) occurs when atmospheric nitrogen is converted to ammonia by an enzyme called a nitrogenase.[1] The overall reaction for BNF is:

N2 + 16ATP + 8e- + 8H+ -> 2NH3 + H2 + 16ADP + 16Pi

The process is coupled to the hydrolysis of 16 equivalents of ATP and is accompanied by the co-formation of one equivalent of H2. The conversion of N2 into ammonia occurs at a metal cluster called FeMoco, an abbreviation for the iron-molybdenum cofactor. The mechanism proceeds via a series of protonation and reduction steps wherein the FeMoco active site hydrogenates the N2 substrate. In free-living diazotrophs, the nitrogenase-generated ammonia is assimilated into glutamate through the glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase pathway.The microbial nif genes required for nitrogen fixation are widely distributed in diverse environments.

Nitrogenases are rapidly degraded by oxygen. For this reason,

many bacteria cease production of the enzyme in the presence of oxygen.

Many nitrogen-fixing organisms exist only in anaerobic conditions, respiring to draw down oxygen levels, or binding the oxygen with a protein such as leghemoglobin.

Microorganisms that fix nitrogen

Diazotrophs are widespread within domain Bacteria including cyanobacteria (e.g. the highly significant Trichodesmium and Cyanothece), as well as green sulfur bacteria, Azotobacteraceae, rhizobia and Frankia. Several obligately anaerobic bacteria fix nitrogen including many (but not all) Clostridium spp. Some Archaea also fix nitrogen, including several methanogenic taxa, which are significant contributors to nitrogen fixation in oxygen-deficient soils.

Cyanobacteria inhabit nearly all illuminated environments on Earth and play key roles in the carbon and nitrogen cycle of the biosphere. In general, cyanobacteria can use various inorganic and organic sources of combined nitrogen, like nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, urea, or some amino acids. Several cyanobacterial strains are also capable of diazotrophic growth, an ability that may have been present in their last common ancestor in the Archean eon. Nitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria in coral reefs

can fix twice as much nitrogen as on land—around 1.8 kg of nitrogen is

fixed per hectare per day (around 660 kg/ha/year). The colonial marine

cyanobacterium Trichodesmium

is thought to fix nitrogen on such a scale that it accounts for almost

half of the nitrogen fixation in marine systems globally.

Root nodule symbioses

The legume family

Plants that contribute to nitrogen fixation include those of the legume family – Fabaceae – with taxa such as kudzu, clovers, soybeans, alfalfa, lupines, peanuts, and rooibos. They contain symbiotic bacteria called rhizobia within nodules in their root systems, producing nitrogen compounds that help the plant to grow and compete with other plants. When the plant dies, the fixed nitrogen is released, making it available to other plants; this helps to fertilize the soil. The great majority of legumes have this association, but a few genera (e.g., Styphnolobium)

do not. In many traditional and organic farming practices, fields are

rotated through various types of crops, which usually include one

consisting mainly or entirely of clover or buckwheat (non-legume family Polygonaceae), often referred to as "green manure".

The efficiency of nitrogen fixation in soil is dependent on many

factors, including the legume as well as air and soil conditions. For

example, nitrogen fixation by red clover can range from 50 -

200 lb./acre depending on these variables.

Inga alley farming relies on the leguminous genus Inga, a small tropical, tough-leaved, nitrogen-fixing tree.

Non-leguminous

A sectioned alder tree root nodule

Although by far the majority of plant species able to form nitrogen-fixing root nodules are in the legume family Fabaceae, there are exceptions:

- Parasponia, a tropical genus in the Cannabaceae also able to interact with rhizobia and form nitrogen-fixing nodules

- Actinorhizal plants such as alder and bayberry can also form nitrogen-fixing nodules, thanks to a symbiotic association with Frankia bacteria. These plants belong to 25 genera distributed among 8 plant families.

The ability to fix nitrogen is present in the families listed below. They belong to the orders Cucurbitales, Fagales, and Rosales, which together with the Fabales form a clade of eurosids. The ability to fix nitrogen is not universally present in these families. For example, of 122 genera in the Rosaceae,

only 4 genera are capable of fixing nitrogen. Fabales were the first

lineage to branch off this nitrogen-fixing clade; thus, the ability to

fix nitrogen may be plesiomorphic and subsequently lost in most descendants of the original nitrogen-fixing plant; however, it may be that the basic genetic and physiological requirements were present in an incipient state in the most recent common ancestors of all these plants, but only evolved to full function in some of them.

There are also several nitrogen-fixing symbiotic associations that involve cyanobacteria (such as Nostoc):

- Some lichens such as Lobaria and Peltigera

- Mosquito fern (Azolla species)

- Cycads

- Gunnera

- Blasia (liverwort)

- Hornworts

Endosymbiosis in diatoms

Rhopalodia gibba, a diatom alga, is a eukaryote with cyanobacterial N2-fixing endosymbiont organelles. The spheroid bodies reside in the cytoplasm of the diatoms and are inseparable from their hosts.

Industrial nitrogen fixation

The possibility that atmospheric nitrogen reacts with certain chemicals was first observed by Desfosses in 1828. He observed that mixtures of alkali metal oxides and carbon react at high temperatures with nitrogen. With the use of barium carbonate

as starting material the first commercially used process became

available in the 1860s developed by Margueritte and Sourdeval. The

resulting barium cyanide could be reacted with steam yielding ammonia. In 1898 Adolph Frank and Nikodem Caro decoupled the process and first produced calcium carbide and in a subsequent step reacted it with nitrogen to calcium cyanamide. The Ostwald process for the production of nitric acid was discovered in 1902. Frank-Caro process and Ostwald process dominated the industrial fixation of nitrogen until the discovery of the Haber process in 1909.

Prior to 1900, Nikola Tesla

also experimented with the industrial fixation of nitrogen "by using

currents of extremely high frequency or rate of vibration".

Haber process

Equipment for a study of nitrogen fixation by alpha rays (Fixed Nitrogen Research Laboratory, 1926)

Artificial fertilizer production is now the largest source of human-produced fixed nitrogen in the Earth's ecosystem. Ammonia is a required precursor to fertilizers, explosives, and other products. The most common method is the Haber process.

The Haber process requires high pressures (around 200 atm) and high

temperatures (at least 400 °C), routine conditions for industrial

catalysis. This highly efficient process uses natural gas as a hydrogen

source and air as a nitrogen source.

Much research has been conducted on the discovery of catalysts

for nitrogen fixation, often with the goal of reducing the energy

required for this conversion. However, such research has thus far failed

to even approach the efficiency and ease of the Haber process. Many

compounds react with atmospheric nitrogen to give dinitrogen complexes. The first dinitrogen complex to be reported was Ru(NH3)5(N2)2+.

Ambient nitrogen reduction

Catalytic

chemical nitrogen fixation at ambient conditions is an ongoing

scientific endeavor. Guided by the example of nitrogenase, this area of

homogeneous catalysis is ongoing, with particular emphasis on

hydrogenation to give ammonia.

Metallic lithium has long been known for burning in an atmosphere of nitrogen and then converting to lithium nitride. Hydrolysis of the resulting nitride gives ammonia. In a related process, trimethylsilyl chloride, lithium, and nitrogen react in the presence of a catalyst to give tris(trimethylsilyl)amine. Tris(trimethylsilyl)amine can then be used for reaction with α,δ,ω-triketones to give tricyclic pyrroles. Processes involving lithium metal are however of no practical interest since they are non-catalytic and re-reducing the Li+ ion residue is difficult.

Beginning in the 1960s several homogeneous systems were

identified that convert nitrogen to ammonia, sometimes even

catalytically but often operating via ill-defined mechanisms. The

original discovery is described in an early review:

"Vol'pin and co-workers, using a non-protic Lewis acid, aluminium tribromide, were able to demonstrate the truly catalytic effect of titanium by treating dinitrogen with a mixture of titanium tetrachloride, metallic aluminium, and aluminium tribromide at 50 °C, either in the absence or in the presence of a solvent, e.g. benzene. As much as 200 mol of ammonia per mol of TiCl4 was obtained after hydrolysis.…"

Synthetic nitrogen reduction

The quest for well defined intermediates led to the characterization of many transition metal dinitrogen complexes.

Few of these well-defined complexes function catalytically, their

behavior illuminated likely stages in nitrogen fixation. Fruitful early

studies focused on M(N2)2(dppe)2 (M = Mo, W), which protonates to give intermediates with ligand M=N−NH2. In 1995, a molybdenum(III) amido complex was discovered that cleaved N2 to give the corresponding molybdenum(VI) nitride. This and related terminal nitrido complexes have been used to make nitriles.

In 2003 a molybdenum amido complex was found to catalyze the reduction of N2, albeit with few turnovers.

In these systems, like the biological one, hydrogen is provided to the

substrate heterolytically, by means of protons and a strong reducing agent rather than with H2 itself.

In 2011, yet another molybdenum-based system was discovered, but with a diphosphorus pincer ligand. Photolytic nitrogen splitting is also considered.

Braunschweig's 2018 dinitrogen activation with a transient borylene species

Nitrogen fixation at a p-block element was published in 2018 whereby one molecule of dinitrogen is bound by two transient Lewis-base-stabilized borylene species. The resulting dianion was subsequently oxidized to a neutral compound, and reduced using water.

Photochemical and Electrochemical Nitrogen Reduction

With

the help of catalysis and energy provided by electricity and light, NH3

can be producted directly from Nitrogen and water at ambient

temperature and pressure.