| Roe v. Wade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued December 13, 1971 Reargued October 11, 1972 Decided January 22, 1973 | |

| Full case name | Jane Roe, et al. v. Henry Wade, District Attorney of Dallas County |

| Citations | 410 U.S. 113 (more)

93 S. Ct. 705; 35 L. Ed. 2d 147; 1973 U.S. LEXIS 159

|

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Reargument | Reargument |

| Decision | Opinion |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for plaintiffs, injunction denied, 314 F. Supp. 1217 (N.D. Tex. 1970); probable jurisdiction noted, 402 U.S. 941 (1971); set for reargument, 408 U.S. 919 (1972) |

| Subsequent | Rehearing denied, 410 U.S. 959 (1973) |

| Holding | |

| Texas law making it a crime to assist a woman to get an abortion violated her due process rights. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas affirmed in part, reversed in part. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Blackmun, joined by Burger, Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, Marshall, Powell |

| Concurrence | Burger |

| Concurrence | Douglas |

| Concurrence | Stewart |

| Dissent | White, joined by Rehnquist |

| Dissent | Rehnquist |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Amend. XIV; Tex. Code Crim. Proc. arts. 1191–94, 1196 | |

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides a fundamental "right to privacy" that protects a pregnant woman's liberty to choose whether or not to have an abortion. It also ruled that this "right to privacy" is not absolute and must be balanced against the government's interests in protecting women's health and protecting prenatal life. The Court resolved this balancing test by tying state regulation of abortion to the three trimesters of pregnancy: the Court ruled that during the first trimester, governments could not prohibit abortions at all; during the second trimester, governments could require reasonable health regulations; during the third trimester, abortions could be prohibited entirely so long as the laws contained exceptions for cases when abortion was necessary to save the life of the mother. Because the Court classified the right to choose to have an abortion as "fundamental", the decision required courts to evaluate challenged abortion laws under the "strict scrutiny" standard, the highest level of judicial review in the United States.

In disallowing many state and federal restrictions on abortion in the United States, Roe v. Wade prompted a national debate that continues today about issues including whether, and to what extent, abortion should be legal, who should decide the legality of abortion, what methods the Supreme Court should use in constitutional adjudication, and what the role should be of religious and moral views in the political sphere. Roe v. Wade reshaped national politics, dividing much of the United States into pro-life and pro-choice camps, while activating grassroots movements on both sides. Roe was criticized by some in the legal community, with the decision being seen as a form of judicial activism. In a 1973 article in the Yale Law Journal, the American legal scholar John Hart Ely criticized Roe as a decision that "is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be." The American constitutional law Laurence Tribe had similar thoughts: "One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found."

In 1992, the Supreme Court revisited and modified its legal rulings in Roe in the case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey. In Casey, the Court reaffirmed Roe's holding that a woman's right to abort a nonviable fetus is constitutionally protected, but abandoned Roe's trimester framework in favor of a standard based on fetal viability, and overruled Roe's requirement that government regulations on abortion be subjected to the strict scrutiny standard. The Roe decision defined "viable" as "potentially able to live outside the mother's womb, albeit with artificial aid." Justices in Casey acknowledged that viability may occur at 23 or 24 weeks, or sometimes even earlier, in light of medical advances.

Background

History of abortion laws in the United States

According to the Court, "the restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a majority of States today are of relatively recent vintage." Providing a historical analysis on abortion, Justice Harry Blackmun noted that abortion was "resorted to without scruple" in Greek and Roman times. Blackmun also addressed the permissive and restrictive abortion attitudes and laws throughout history, noting the disagreements among leaders (of all different professions) in those eras and the formative laws and cases. In the United States, in 1821, Connecticut passed the first state statute criminalizing abortion. Every state had abortion legislation by 1900. In the United States, abortion was sometimes considered a common law crime, though Justice Blackmun would conclude that the criminalization of abortion did not have "roots in the English common-law tradition." Rather than arresting the women having the abortions, legal officials were more likely to interrogate these women to obtain evidence against the abortion provider in order to close down that provider's business.In 1971, Shirley Wheeler was charged with manslaughter after Florida hospital staff reported her illegal abortion to the police. She received a sentence of two years' probation and, under her probation, had to move back into her parents' house in North Carolina. The Boston Women's Abortion Coalition held a rally for Wheeler in Boston to raise money and awareness of her charges as well as had staff members from the Women's National Abortion Action Coalition (WONAAC) speak at the rally. Wheeler was possibly the first woman to be held criminally responsible for submitting to an abortion. Her conviction was overturned by the Florida Supreme Court.

History of the case

In June 1969, 21-year-old Norma McCorvey discovered she was pregnant with her third child. She returned to Dallas, Texas, where friends advised her to assert falsely that she had been raped in order to obtain a legal abortion (with the incorrect assumption that Texas law allowed abortion in cases of rape and incest). This scheme would also fail because there was no police report documenting the alleged rape. In any case, the Texas statute allowed abortion only ”for the purpose of saving the life of the mother”. She attempted to obtain an Illegal abortion, but found that the unauthorized facility had been closed down by the police. Eventually, she was referred to attorneys Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington. (McCorvey would end up giving birth before the case was decided, and the child was put up for adoption.)In 1970, Coffee and Weddington filed suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas on behalf of McCorvey (under the alias Jane Roe). The defendant in the case was Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade, who represented the State of Texas. McCorvey was no longer claiming her pregnancy was a result of rape, and later acknowledged that she had lied about having been raped. "Rape" is not mentioned in the judicial opinions in the case.

On June 17, 1970, a three-judge panel of the District Court, consisting of Northern District of Texas Judges Sarah T. Hughes, William McLaughlin Taylor Jr. and Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Irving Loeb Goldberg, unanimously declared the Texas law unconstitutional, finding that it violated the right to privacy found in the Ninth Amendment. In addition, the court relied on Justice Arthur Goldberg's 1965 concurrence in Griswold v. Connecticut. The court, however, declined to grant an injunction against enforcement of the law.

Issues before the Supreme Court

Roe v. Wade reached the Supreme Court on appeal in 1970. The justices delayed taking action on Roe and a closely related case, Doe v. Bolton, until they had decided Younger v. Harris (because they felt the appeals raised difficult questions on judicial jurisdiction) and United States v. Vuitch (in which they considered the constitutionality of a District of Columbia statute that criminalized abortion except where the mother's life or health was endangered). In Vuitch, the Court narrowly upheld the statute, though in doing so, it treated abortion as a medical procedure and stated that physicians must be given room to determine what constitutes a danger to (physical or mental) health. The day after they announced their decision in Vuitch, they voted to hear both Roe and Doe.Arguments were scheduled by the full Court for December 13, 1971. Before the Court could hear the oral arguments, Justices Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II retired. Chief Justice Warren Burger asked Justice Potter Stewart and Justice Blackmun to determine whether Roe and Doe, among others, should be heard as scheduled. According to Blackmun, Stewart felt that the cases were a straightforward application of Younger v. Harris, and they recommended that the Court move forward as scheduled.

In his opening argument in defense of the abortion restrictions, attorney Jay Floyd made what was later described as the "worst joke in legal history." Appearing against two female lawyers, Floyd began, "Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court. It's an old joke, but when a man argues against two beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word." His remark was met with cold silence; one observer thought that Chief Justice Burger "was going to come right off the bench at him. He glared him down."

After a first round of arguments, all seven justices tentatively agreed that the Texas law should be struck down, but on varying grounds. Burger assigned the role of writing the Court's opinion in Roe (as well as Doe) to Blackmun, who began drafting a preliminary opinion that emphasized what he saw as the Texas law's vagueness. (At this point, Black and Harlan had been replaced by Justices William Rehnquist and Lewis F. Powell Jr., but they arrived too late to hear the first round of arguments.) But Blackmun felt that his opinion did not adequately reflect his liberal colleagues' views. In May 1972, he proposed that the case be reargued. Justice William O. Douglas threatened to write a dissent from the reargument order (he and the other liberal justices were suspicious that Rehnquist and Powell would vote to uphold the statute), but was coaxed out of the action by his colleagues, and his dissent was merely mentioned in the reargument order without further statement or opinion. The case was reargued on October 11, 1972. Weddington continued to represent Roe, and Texas Assistant Attorney General Robert C. Flowers replaced Jay Floyd for Texas.

Blackmun continued to work on his opinions in both cases over the summer recess, even though there was no guarantee that he would be assigned to write them again. Over the recess, he spent a week researching the history of abortion at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he had worked in the 1950s. After the Court heard the second round of arguments, Powell said he would agree with Blackmun's conclusion but pushed for Roe to be the lead of the two abortion cases being considered. Powell also suggested that the Court strike down the Texas law on privacy grounds. Justice Byron White was unwilling to sign on to Blackmun's opinion, and Rehnquist had already decided to dissent.

Prior to the decision, the justices discussed the trimester framework at great length. Justice Powell had suggested that the point where the state could intervene be placed at viability, which Justice Thurgood Marshall supported as well. In an internal memo to the other justices before the majority decision was published, Justice Blackmun wrote: "You will observe that I have concluded that the end of the first trimester is critical. This is arbitrary, but perhaps any other selected point, such as quickening or viability, is equally arbitrary." Roe supporters are quick to point out, however, that the memo only reflects Blackmun's uncertainty about the timing of the trimester framework, not the framework or the holding itself. In his opinion, Blackmun also clearly explained how he had reached the trimester framework – scrutinizing history, common law, the Hippocratic Oath, medical knowledge, and the positions of medical organizations. Justice Blackmun's trimester framework was later rejected by the O'Connor–Souter–Kennedy plurality in Casey, in favor of the "undue burden" analysis still employed by the Court. Contrary to Blackmun, Justice Douglas preferred the first-trimester line. Justice Stewart said the lines were "legislative" and wanted more flexibility and consideration paid to state legislatures, though he joined Blackmun's decision. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. proposed abandoning frameworks based on the age of the fetus and instead allowing states to regulate the procedure based on its safety for the mother.

Supreme Court decision

On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision in favor of Roe that struck down Texas's abortion ban as unconstitutional. In addition to the majority opinion, Justices Burger, Douglas, and Stewart each filed concurring opinions, and Justice White filed a dissenting opinion in which Justice Rehnquist joined. Burger's, Douglas's, and White's opinions were issued along with the Court's opinion in Doe v. Bolton (announced on the same day as Roe v. Wade).Opinion of the Court

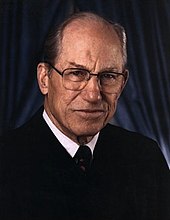

Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade.

Seven justices formed the majority and joined an opinion written by Justice Harry Blackmun. The Court began by exhaustively reviewing the legality of abortion throughout the history of Roman law and the Anglo-American common law up until the 20th century. It also reviewed the developments of medical procedures and technology to perform abortions safely.

Right to privacy

With its historical survey as background, the Court centered its

opinion around the notion of a constitutional "right to privacy" that

was intimated in earlier cases involving family relationships and

reproductive autonomy. After reviewing these cases, the Court proceeded, "with virtually no further explanation of the privacy value",

to rule that regardless of exactly which provisions were involved, the

U.S. Constitution's guarantees of liberty covered a right to privacy

that generally protected a pregnant woman's decision whether or not to

abort a pregnancy.

This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or ... in the Ninth Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 153.

The Court reasoned that outlawing abortions would infringe a pregnant

woman's right to privacy for several reasons: having unwanted children

"may force upon the woman a distressful life and future"; it may bring

imminent psychological harm; caring for the child may tax the mother's

physical and mental health; and because there may be "distress, for all

concerned, associated with the unwanted child."

However, the Court rejected the notion that a pregnant woman's right to

abort her pregnancy was absolute, and held that the right must be

balanced against other considerations such as the state's interest in

protecting "prenatal life."

The Court acknowledged that states had two interests that were

sufficiently "compelling" to permit some limitations on the right to

choose to have an abortion: their interests in protecting the mother's

health and protecting the life of the fetus. The Court rejected Texas's

argument that total bans on abortion were justifiable because "life"

begins at the moment of conception.

The Court found that there was no indication that the Constitution's

uses of the word "person" were meant to include fetuses, and so it

rejected Texas's argument that a fetus should be considered a "person"

with a legal and constitutional right to life. It noted that there was still great disagreement over when an unborn fetus becomes a "person".

We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, in this point in the development of man's knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 159.

The Court settled on the three trimesters of pregnancy as the framework to resolve the problem. During the first trimester, when it was believed that the procedure was safer than childbirth,

the Court ruled that the government could place no restriction on a

woman's ability to choose to abort a pregnancy other than minimal

medical safeguards such as requiring a licensed physician to perform the

procedure.

From the second trimester on, the Court ruled that evidence of

increasing risks to the mother's health gave the state a compelling

interest, and that it could enact medical regulations on the procedure

so long as they were reasonable and "narrowly tailored" to protecting

mothers' health.

At the level of medical science available in the early 1970s, the

beginning of the third trimester was normally considered to be the point

at which a fetus became viable. Therefore, the Court ruled that during

the third trimester the state had a compelling interest in protecting

prenatal life, and could legally prohibit all abortions except where

necessary to protect the mother's life or health.

Justiciability

An aspect of the decision that attracted comparatively little attention was the Court's disposition of the issues of standing and mootness.

Under the traditional interpretation of these rules, Jane Roe's appeal

was "moot" because she had already given birth to her child and thus

would not be affected by the ruling; she also lacked "standing" to

assert the rights of other pregnant women. As she did not present an "actual case or controversy" (a grievance and a demand for relief), any opinion issued by the Supreme Court would constitute an advisory opinion.

The Court concluded that the case came within an established

exception to the rule: one that allowed consideration of an issue that

was "capable of repetition, yet evading review." This phrase had been coined in 1911 by Justice Joseph McKenna in Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. ICC.

Blackmun's opinion quoted McKenna and noted that pregnancy would

normally conclude more quickly than an appellate process: "If that

termination makes a case moot, pregnancy litigation seldom will survive

much beyond the trial stage, and appellate review will be effectively

denied."

Concurrences

Several other members of the Supreme Court filed concurring opinions in the case. Justice Potter Stewart

wrote a concurring opinion in which he stated that even though the

Constitution makes no mention of the right to choose to have an abortion

without interference, he thought the Court's decision was a permissible

interpretation of the doctrine of substantive due process, which says that the Due Process Clause's protection of liberty extends beyond simple procedures and protects certain fundamental rights. Justice William O. Douglas

wrote a concurring opinion in which he described how he believed that

while the Court was correct to find that the right to choose to have an

abortion was a fundamental right, it would be better to derive it from

the Ninth Amendment –

which states that the fact that a right is not specifically enumerated

in the Constitution shall not be construed to mean that American people

do not possess it – rather than through the Fourteenth Amendment's Due

Process Clause.

Dissents

Byron White was the senior dissenting justice.

Only two justices dissented from the Court's decision, but their

dissents touched on the points that would lead to later criticism of the

Roe decision.

Justice Byron White

wrote a dissenting opinion in which he stated his belief that the Court

had no basis for deciding between the competing values of pregnant

women and unborn children. He wrote:

I find nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the Court's judgment. The Court simply fashions and announces a new constitutional right for pregnant women and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invests that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes. The upshot is that the people and the legislatures of the 50 States are constitutionally disentitled to weigh the relative importance of the continued existence and development of the fetus, on the one hand, against a spectrum of possible impacts on the woman, on the other hand. As an exercise of raw judicial power, the Court perhaps has authority to do what it does today; but, in my view, its judgment is an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review that the Constitution extends to this Court.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 221–22 (White, J., dissenting).

White asserted that the Court "values the convenience of the pregnant

mother more than the continued existence and development of the life or

potential life that she carries." Though he suggested that he "might

agree" with the Court's values and priorities, he wrote that he saw "no

constitutional warrant for imposing such an order of priorities on the

people and legislatures of the States." White criticized the Court for

involving itself in the issue of abortion by creating "a constitutional

barrier to state efforts to protect human life and by investing mothers

and doctors with the constitutionally protected right to exterminate

it." He would have left this issue, for the most part, "with the people

and to the political processes the people have devised to govern their

affairs."

Justice William Rehnquist

also dissented from the Court's decision. In his dissenting opinion, he

compared the majority's use of substantive due process to the Court's

repudiated use of the doctrine in the 1905 case Lochner v. New York. He elaborated on several of White's points, asserting that the Court's historical analysis was flawed:

To reach its result, the Court necessarily has had to find within the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment a right that was apparently completely unknown to the drafters of the Amendment. As early as 1821, the first state law dealing directly with abortion was enacted by the Connecticut Legislature. By the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, there were at least 36 laws enacted by state or territorial legislatures limiting abortion. While many States have amended or updated their laws, 21 of the laws on the books in 1868 remain in effect today.

— Roe, 410 U.S. at 174–76 (Rehnquist, J., dissenting).

From this historical record, Rehnquist concluded, "There apparently

was no question concerning the validity of this provision or of any of

the other state statutes when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted."

Therefore, in his view, "the drafters did not intend to have the

Fourteenth Amendment withdraw from the States the power to legislate

with respect to this matter."

Reception

Political

A statistical evaluation of the relationship of political

affiliation to pro-choice and anti-abortion issues shows that public

opinion is much more nuanced about when abortion is acceptable than is

commonly assumed.

The most prominent organized groups that mobilized in response to Roe are the National Abortion Rights Action League and the National Right to Life Committee.

Support

Advocates of Roe describe it as vital to the preservation of women's rights,

personal freedom, bodily integrity, and privacy. Advocates have also

reasoned that access to safe abortion and reproductive freedom generally

are fundamental rights. Some scholars (not including any member of the

Supreme Court) have equated the denial of abortion rights to compulsory

motherhood, and have argued that abortion bans therefore violate the Thirteenth Amendment:

When women are compelled to carry and bear children, they are subjected to 'involuntary servitude' in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment….[E]ven if the woman has stipulated to have consented to the risk of pregnancy, that does not permit the state to force her to remain pregnant.

Supporters of Roe contend that the decision has a valid

constitutional foundation in the Fourteenth Amendment, or that the

fundamental right to abortion is found elsewhere in the Constitution but

not in the articles referenced in the decision.

Opposition

Every year, on the anniversary of the decision, opponents of abortion march up Constitution Avenue to the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., in the March for Life. Around 250,000 people attended the march until 2010. Estimates put the 2011 and 2012 attendances at 400,000 each, and the 2013 March for Life drew an estimated 650,000 people.

Opponents of Roe assert that the decision lacks a valid constitutional foundation. Like the dissenters in Roe,

they maintain that the Constitution is silent on the issue, and that

proper solutions to the question would best be found via state

legislatures and the legislative process, rather than through an

all-encompassing ruling from the Supreme Court.

A prominent argument against the Roe decision is that, in the absence of consensus about when meaningful life begins, it is best to avoid the risk of doing harm.

In response to Roe v. Wade, most states enacted or attempted to enact laws limiting or regulating abortion, such as laws requiring parental consent or parental notification for minors to obtain abortions; spousal mutual consent laws; spousal notification

laws; laws requiring abortions to be performed in hospitals, not

clinics; laws barring state funding for abortions; laws banning intact dilation and extraction,

also known as partial-birth abortion; laws requiring waiting periods

before abortions; and laws mandating that women read certain types of

literature and watch a fetal ultrasound before undergoing an abortion. In 1976, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment,

barring federal funding of abortions (except in cases of rape, incest,

or a threat to the life of the mother) for poor women through the Medicaid

program. The Supreme Court struck down some state restrictions in a

long series of cases stretching from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s,

but upheld restrictions on funding, including the Hyde Amendment, in the

case of Harris v. McRae (1980).

Some opponents of abortion maintain that personhood begins at fertilization or conception, and should therefore be protected by the Constitution; the dissenting justices in Roe

instead wrote that decisions about abortion "should be left with the

people and to the political processes the people have devised to govern

their affairs."

Perhaps the most notable opposition to Roe comes from Roe herself: In 1995, Norma L. McCorvey revealed that she had become pro-life, and from then until her death in 2017, she was a vocal opponent of abortion.

Legal

Justice Blackmun, who authored the Roe decision, stood by the analytical framework he established in Roe throughout his career. Despite his initial reluctance, he became the decision's chief champion and protector during his later years on the Court.

Liberal and feminist legal scholars have had various reactions to Roe,

not always giving the decision unqualified support. One argument is

that Justice Blackmun reached the correct result but went about it the

wrong way. Another is that the end achieved by Roe does not justify its means of judicial fiat.

Justice John Paul Stevens,

while agreeing with the decision, has suggested that it should have

been more narrowly focused on the issue of privacy. According to

Stevens, if the decision had avoided the trimester framework and simply

stated that the right to privacy included a right to choose abortion,

"it might have been much more acceptable" from a legal standpoint. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had, before joining the Court, criticized the decision for ending a nascent movement to liberalize abortion law through legislation.

Ginsburg has also faulted the Court's approach for being "about a

doctor's freedom to practice his profession as he thinks best.... It

wasn't woman-centered. It was physician-centered." Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox wrote: "[Roe's]

failure to confront the issue in principled terms leaves the opinion to

read like a set of hospital rules and regulations.... Neither

historian, nor layman, nor lawyer will be persuaded that all the

prescriptions of Justice Blackmun are part of the Constitution."

In a highly cited 1973 article in the Yale Law Journal, Professor John Hart Ely criticized Roe as a decision that "is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be."[86] Ely added: "What is frightening about Roe

is that this super-protected right is not inferable from the language

of the Constitution, the framers’ thinking respecting the specific

problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they

included, or the nation's governmental structure." Professor Laurence Tribe had similar thoughts: "One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found." Liberal law professors Alan Dershowitz, Cass Sunstein, and Kermit Roosevelt have also expressed disappointment with Roe.

Jeffrey Rosen and Michael Kinsley

echo Ginsburg, arguing that a legislative movement would have been the

correct way to build a more durable consensus in support of abortion

rights. William Saletan wrote, "Blackmun's [Supreme Court] papers vindicate every indictment of Roe: invention, overreach, arbitrariness, textual indifference." Benjamin Wittes has written that Roe "disenfranchised millions of conservatives on an issue about which they care deeply." And Edward Lazarus, a former Blackmun clerk who "loved Roe's author like a grandfather," wrote: "As a matter of constitutional interpretation and judicial method, Roe

borders on the indefensible.... Justice Blackmun's opinion provides

essentially no reasoning in support of its holding. And in the almost 30

years since Roe's announcement, no one has produced a convincing defense of Roe on its own terms."

The assertion that the Supreme Court was making a legislative decision is often repeated by opponents of the ruling.

The "viability" criterion is still in effect, although the point of

viability has changed as medical science has found ways to help

premature babies survive.

Public opinion

Americans have been equally divided on the issue; a May 2018 Gallup poll

indicated that 48% of Americans described themselves as pro-choice and

48% described themselves as pro-life. A July 2018 poll indicated that

only 28% of Americans wanted the Supreme Court to overturn Roe vs. Wade,

while 64% did not want the ruling to be overturned.

A Gallup poll

conducted in May 2009 indicated that 53% of Americans believed that

abortions should be legal under certain circumstances, 23% believed

abortion should be legal under any circumstances, and 22% believed that

abortion should be illegal in all circumstances. However, in this poll,

more Americans referred to themselves as "Pro-Life" than "Pro-Choice"

for the first time since the poll asked the question in 1995, with 51%

identifying as "Pro-Life" and 42% identifying as "Pro-Choice". Similarly, an April 2009 Pew Research Center

poll showed a softening of support for legal abortion in all cases

compared to the previous years of polling. People who said they support

abortion in all or most cases dropped from 54% in 2008 to 46% in 2009.

In contrast, an October 2007 Harris poll on Roe v. Wade asked the following question:

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that states laws which made it illegal for a woman to have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy were unconstitutional, and that the decision on whether a woman should have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy should be left to the woman and her doctor to decide. In general, do you favor or oppose this part of the U.S. Supreme Court decision making abortions up to three months of pregnancy legal?

In reply, 56% of respondents indicated favour while 40% indicated

opposition. The Harris organization concluded from this poll that "56

percent now favours the U.S. Supreme Court decision." Anti-abortion

activists have disputed whether the Harris poll question is a valid

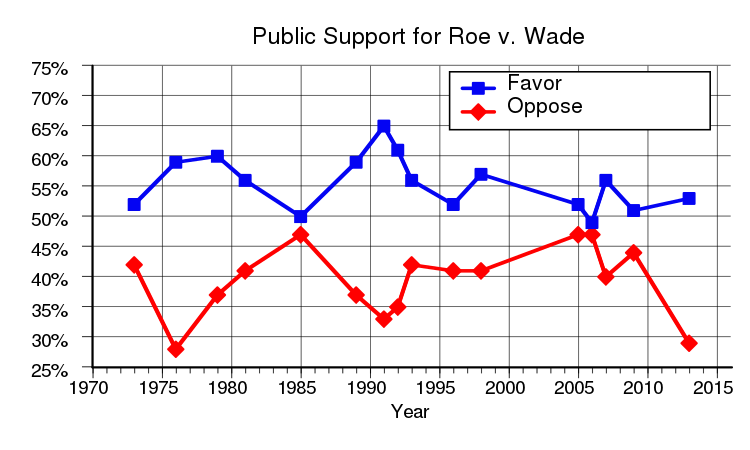

measure of public opinion about Roe's overall decision, because the question focuses only on the first three months of pregnancy. The Harris poll has tracked public opinion about Roe since 1973:

Regarding the Roe decision as a whole, more Americans support it than support overturning it. When pollsters describe various regulations that Roe prevents legislatures from enacting, support for Roe drops.

Role in subsequent decisions and politics

Opposition to Roe on the bench grew when President Reagan, who

supported legislative restrictions on abortion, began making federal

judicial appointments in 1981. Reagan denied that there was any litmus test:

"I have never given a litmus test to anyone that I have appointed to

the bench…. I feel very strongly about those social issues, but I also

place my confidence in the fact that the one thing that I do seek are

judges that will interpret the law and not write the law. We've had too

many examples in recent years of courts and judges legislating."

In addition to White and Rehnquist, Reagan appointee Sandra Day O'Connor began dissenting from the Court's abortion cases, arguing in 1983 that the trimester-based analysis devised by the Roe Court was "unworkable." Shortly before his retirement from the bench, Chief Justice Warren Burger suggested in 1986 that Roe be "reexamined"; the associate justice who filled Burger's place on the Court – Justice Antonin Scalia – vigorously opposed Roe. Concern about overturning Roe played a major role in the defeat of Robert Bork's nomination to the Court in 1987; the man eventually appointed to replace Roe-supporter Lewis Powell was Anthony Kennedy.

The Supreme Court of Canada used the rulings in both Roe and Doe v. Bolton as grounds to find Canada's federal law restricting access to abortions unconstitutional. That Canadian case, R. v. Morgentaler, was decided in 1988.

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services

In a 5–4 decision in 1989's Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, Chief Justice Rehnquist, writing for the Court, declined to explicitly overrule Roe, because "none of the challenged provisions of the Missouri Act properly before us conflict with the Constitution." In this case, the Court upheld several abortion restrictions, and modified the Roe trimester framework.

In concurring opinions, O'Connor refused to reconsider Roe, and Justice Antonin Scalia criticized the Court and O'Connor for not overruling Roe. Blackmun – author of the Roe

decision – stated in his dissent that White, Kennedy and Rehnquist were

"callous" and "deceptive," that they deserved to be charged with

"cowardice and illegitimacy," and that their plurality opinion "foments disregard for the law." White had recently opined that the majority reasoning in Roe v. Wade was "warped."

Planned Parenthood v. Casey

During initial deliberations for Planned Parenthood v. Casey

(1992), an initial majority of five Justices (Rehnquist, White, Scalia,

Kennedy, and Thomas) were willing to effectively overturn Roe. Kennedy changed his mind after the initial conference, and O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter joined Blackmun and Stevens to reaffirm the central holding of Roe,

saying, "Our law affords constitutional protection to personal

decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family

relationships, child rearing, and education. [...] These matters,

involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a

lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy, are central

to the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. At the heart of

liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of

meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life." Only Justice Blackmun would have retained Roe entirely and struck down all aspects of the statute at issue in Casey.

Scalia's dissent acknowledged that abortion rights are of "great

importance to many women", but asserted that it is not a liberty

protected by the Constitution, because the Constitution does not mention

it, and because longstanding traditions have permitted it to be legally

proscribed. Scalia concluded: "[B]y foreclosing all democratic outlet

for the deep passions this issue arouses, by banishing the issue from

the political forum that gives all participants, even the losers, the

satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight, by continuing the

imposition of a rigid national rule instead of allowing for regional

differences, the Court merely prolongs and intensifies the anguish."

Stenberg v. Carhart

During the 1990s, the state of Nebraska attempted to ban a certain second-trimester abortion procedure known as intact dilation and extraction (sometimes called partial birth abortion). The Nebraska ban allowed other second-trimester abortion procedures called dilation and evacuation

abortions. Ginsburg (who replaced White) stated, "this law does not

save any fetus from destruction, for it targets only 'a method of

performing abortion'." The Supreme Court struck down the Nebraska ban by a 5–4 vote in Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), citing a right to use the safest method of second trimester abortion.

Kennedy, who had co-authored the 5–4 Casey decision upholding Roe, was among the dissenters in Stenberg, writing that Nebraska had done nothing unconstitutional.

In his dissent, Kennedy described the second trimester abortion

procedure that Nebraska was not seeking to prohibit, and thus argued

that since this dilation and evacuation procedure remained available in

Nebraska, the state was free to ban the other procedure sometimes called

"partial birth abortion."

The remaining three dissenters in Stenberg – Rehnquist, Scalia, and Thomas – disagreed again with Roe: "Although a State may permit abortion, nothing in the Constitution dictates that a State must do so."

Gonzales v. Carhart

In 2003, Congress passed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which led to a lawsuit in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart. The Court had previously ruled in Stenberg v. Carhart

that a state's ban on "partial birth abortion" was unconstitutional

because such a ban did not have an exception for the health of the

woman. The membership of the Court changed after Stenberg, with John Roberts and Samuel Alito replacing Rehnquist and O'Connor, respectively. Further, the ban at issue in Gonzales v. Carhart was a clear federal statute, rather than a relatively vague state statute as in the Stenberg case.

On April 18, 2007, the Supreme Court handed down a 5 to 4

decision upholding the constitutionality of the Partial-Birth Abortion

Ban Act. Kennedy wrote the majority opinion, asserting that Congress was

within its power to generally ban the procedure, although the Court

left the door open for as-applied challenges. Kennedy's opinion did not

reach the question of whether the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and Stenberg v. Carhart

remained valid, and instead the Court stated that the challenged

statute remained consistent with those past decisions whether or not

those decisions remained valid.

Chief Justice John Roberts,

Scalia, Thomas, and Alito joined the majority. Justices Ginsburg,

Stevens, Souter, and Breyer dissented, contending that the ruling

ignored Supreme Court abortion precedent, and also offering an

equality-based justification for abortion precedent. Thomas filed a

concurring opinion, joined by Scalia, contending that the Court's prior

decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey should be reversed, and also noting that the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act possibly exceeded the powers of Congress under the Commerce Clause.

Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt

In the case of Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt, the most significant abortion rights case before the Supreme Court since Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992,

the Supreme Court in a 5–3 decision on June 27, 2016, swept away forms

of state restrictions on the way abortion clinics can function.

The

Texas legislature enacted in 2013 restrictions on the delivery of

abortions services that created an undue burden for women seeking an

abortion by requiring abortion doctors to have difficult-to-obtain

"admitting privileges" at a local hospital and by requiring clinics to

have costly hospital-grade facilities. The Court struck down these two

provisions "facially" from the law at issue

– that is, the very words of the provisions were invalid, no matter how

they might be applied in any practical situation. According to the

Supreme Court the task of judging whether a law puts an unconstitutional

burden on a woman's right to abortion belongs with the courts and not

the legislatures.

Activities of Norma McCorvey

Norma McCorvey became a member of the anti-abortion movement in 1995; she supported making abortion illegal until her death in 2017. In 1998, she testified to Congress:

It was my pseudonym, Jane Roe, which had been used to create the "right" to abortion out of legal thin air. But Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee never told me that what I was signing would allow women to come up to me 15, 20 years later and say, "Thank you for allowing me to have my five or six abortions. Without you, it wouldn't have been possible." Sarah never mentioned women using abortions as a form of birth control. We talked about truly desperate and needy women, not women already wearing maternity clothes.

As a party to the original litigation, she sought to reopen the case in U.S. District Court in Texas to have Roe v. Wade overturned. However, the Fifth Circuit decided that her case was moot, in McCorvey v. Hill. In a concurring opinion, Judge Edith Jones

agreed that McCorvey was raising legitimate questions about emotional

and other harm suffered by women who have had abortions, about increased

resources available for the care of unwanted children, and about new

scientific understanding of fetal development, but Jones said she was

compelled to agree that the case was moot. On February 22, 2005, the

Supreme Court refused to grant a writ of certiorari, and McCorvey's appeal ended.

Activities of Sarah Weddington

After arguing before the Court in Roe v. Wade at the age of 26, Sarah Weddington went on to be a representative in the Texas House of Representatives for three terms.

Weddington has also had a long and successful career as General Counsel

for the United States Department of Agriculture, Assistant to President

Jimmy Carter, lecturer at Texas Wesleyan University, and speaker and

adjunct professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

Presidential positions

President Richard Nixon did not publicly comment about the decision. In private conversation later revealed as part of the Nixon tapes, Nixon said "There are times when an abortion is necessary,... ."

However, Nixon was also concerned that greater access to abortions

would foster "permissiveness," and said that "it breaks the family."

Generally, presidential opinion has been split between major party lines. The Roe decision was opposed by Presidents Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush. President George H.W. Bush also opposed Roe, though he had supported abortion rights earlier in his career.

President Jimmy Carter

supported legal abortion from an early point in his political career,

in order to prevent birth defects and in other extreme cases; he

encouraged the outcome in Roe and generally supported abortion rights. Roe was also supported by President Bill Clinton. President Barack Obama has taken the position that "Abortions should be legally available in accordance with Roe v. Wade."

President Donald Trump has publicly opposed the decision, vowing to appoint pro-life justices to the Supreme Court. Upon Justice Kennedy's retirement in 2018, Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh

to replace him, and he was confirmed by the Senate in October 2018. A

central point of Kavanaugh's appointment hearings was his stance on Roe v. Wade, of which he said to Senator Susan Collins that he would not "overturn a long-established precedent if five current justices believed that it was wrongly decided". Despite Kavanaugh's statement, there is concern that with the Supreme Court having a strong conservative majority, that Roe v. Wade

will be overturned given an appropriate case to challenge it. Further

concerns were raised following the May 2019 Supreme Court 5-4 decision

along ideological lines in Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt. While the case had nothing to do with abortion rights, the decision overturned a previous 1979 decision from Nevada v. Hall without maintaining the stare decisis precedent, indicating the current Court makeup would be willing to apply the same to overturn Roe v. Wade. Pro-abortion organizations like Planned Parenthood are planning on how they will operate should Roe v. Wade be overturned.

State laws regarding Roe

Since 2010 there has been an increase in state restrictions on abortion.

Several states have enacted so-called trigger laws which would take effect in the event that Roe v. Wade

is overturned, with the effect of outlawing abortions on the state

level. Those states include Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi,

North Dakota and South Dakota.

Additionally, many states did not repeal pre-1973 statutes that

criminalized abortion, and some of those statutes could again be in

force if Roe were reversed.

Other states have passed laws to maintain the legality of abortion if Roe v. Wade is overturned. Those states include California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Nevada and Washington.

The Mississippi Legislature has attempted to make abortion unfeasible without having to overturn Roe v. Wade. The Mississippi law as of 2012 was being challenged in federal courts and was temporarily blocked.

Alabama House Republicans passed a law on April 30, 2019 that will criminalize abortion if it goes into effect. It offers only two exceptions: serious health risk to the mother or a lethal fetal anomaly. Alabama governor Kay Ivey signed the bill into law on May 14, primarily as a symbolic gesture in hopes of challenging Roe v. Wade in the Supreme Court.