| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Melanesia |

| Coordinates | 5°30′S 141°00′ECoordinates: 5°30′S 141°00′E |

| Archipelago | Indonesian archipelago |

| Area | 785,753 km2 (303,381 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 2nd |

| Highest elevation | 4,884 m (16,024 ft) |

| Highest point | Puncak Jaya |

| Administration | |

| Provinces |

Papua West Papua |

| Largest settlement | Jayapura |

| Provinces |

Central Simbu Eastern Highlands East Sepik Enga Gulf Hela Jiwaka Madang Morobe Oro Southern Highlands Western Western Highlands West Sepik Milne Bay National Capital District |

| Largest settlement | Port Moresby |

| Demographics | |

| Population | ~ 11,306,940 (2014) |

| Pop. density | 14 /km2 (36 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Papuan and Austronesian |

New Guinea (Tok Pisin: Niugini; Dutch: Nieuw-Guinea; German: Neuguinea; Indonesian: Nugini or, more commonly known, Papua, historically, Irian) is a large island off the continent of Australia. It is the world's second-largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 785,753 km2 (303,381 sq mi), and the largest wholly or partly within the Southern Hemisphere and Oceania.

The eastern half of the island is the major land mass of the independent state of Papua New Guinea. The western half, referred to as Western New Guinea or West Papua or simply Papua, formerly a Dutch colony, was annexed by Indonesia in 1962 and has been administered by it since then.

Names

A typical map from the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography. Australasia during the Golden Age of Dutch exploration and discovery (c. 1590s–1720s): including Nova Guinea (New Guinea), Nova Hollandia (mainland Australia), Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), and Nova Zeelandia (New Zealand).

The island has been known by various names:

The name Papua was used to refer to parts of the island before contact with the West.[1] Its etymology is unclear;[1] one theory states that it is from Tidore, the language used by the Sultanate of Tidore, which controlled parts of the island's coastal region.[2] The name came from papo (to unite) and ua (negation), which means "not united" or, "territory that geographically is far away (and thus not united)".[2]

Ploeg reports that the word papua is often said to derive from the Malay word papua or pua-pua, meaning "frizzly-haired", referring to the highly curly hair of the inhabitants of these areas.[3] Another possibility, put forward by Sollewijn Gelpke in 1993, is that it comes from the Biak phrase sup i papwa which means 'the land below [the sunset]' and refers to the islands west of the Bird's Head, as far as Halmahera. Whatever its origin, the name Papua came to be associated with this area, and more especially with Halmahera, which was known to the Portuguese by this name during the era of their colonization in this part of the world.

When the Portuguese and Spanish explorers arrived in the island via the Spice Islands, they also referred to the island as Papua.[2] However, the name New Guinea was later used by Westerners starting with the Spanish explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez in 1545, referring to the similarities of the indigenous people's appearance with the natives of the Guinea region of Africa.[2] The name is one of several toponyms sharing similar etymologies, ultimately meaning "land of the blacks" or similar meanings, in reference to the dark skin of the inhabitants.

The Dutch, who arrived later under Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten, called it Schouten island, but later this name was used only to refer to islands off the north coast of Papua proper, the Schouten Islands or Biak Island. When the Dutch colonized it as part of Netherlands East Indies, they called it Nieuw Guinea.[2]

The name Irian was used in the Indonesian language to refer to the island and Indonesian province, as "Irian Jaya Province". The name was promoted in 1945 by Marcus Kaisiepo,[1] brother of the future governor Frans Kaisiepo. It is taken from the Biak language of Biak Island, and means "to rise", or "rising spirit". Irian is the name used in the Biak language and other languages such as Serui, Merauke and Waropen.[2] The name was used until 2001, when the name Papua was again used for the island and the province. The name Irian, which was originally favored by natives, is now considered to be a name imposed by the authority of Jakarta.[1]

Geography

Regions of Oceania: Australasia, Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. Physiographically, Australasia includes the Australian landmass (including Tasmania), New Zealand, and New Guinea.

New Guinea located in relation to Melanesia

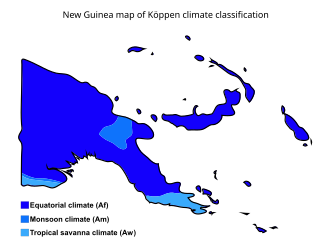

New Guinea map of Köppen climate classification

Topographical map of New Guinea

New Guinea is an island to the north of Australia, but south of the equator. It is isolated by the Arafura Sea to the west, and the Torres Strait and Coral Sea to the east. Sometimes considered to be the easternmost island of the Indonesian archipelago, it lies north of Australia's Top End, the Gulf of Carpentaria and Cape York peninsula, and west of the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands Archipelago.

Politically, the western half of the island comprises two provinces of Indonesia: Papua and West Papua. The eastern half forms the mainland of the country of Papua New Guinea (PNG).

The shape of New Guinea is often compared to that of a bird-of-paradise (indigenous to the island), and this results in the usual names for the two extremes of the island: the Bird's Head Peninsula in the northwest (Vogelkop in Dutch, Kepala Burung in Indonesian; also known as the Doberai Peninsula), and the Bird's Tail Peninsula in the southeast (also known as the Papuan Peninsula).

A spine of east–west mountains, the New Guinea Highlands, dominates the geography of New Guinea, stretching over 1,600 km (1,000 mi) from the 'head' to the 'tail' of the island, with many high mountains over 4,000 m (13,100 ft). The western half of the island of New Guinea contains the highest mountains in Oceania, rising up to 4,884 m (16,024 ft) high, which is even higher than Mont Blanc in Europe, ensuring a steady supply of rain from the equatorial atmosphere. The tree line is around 4,000 m (13,100 ft) elevation and the tallest peaks contain permanent equatorial glaciers—which have been retreating since at least 1936.[4][5][6] Various other smaller mountain ranges occur both north and west of the central ranges. Except in high elevations, most areas possess a warm humid climate throughout the year, with some seasonal variation associated with the northeast monsoon season.

The highest peaks on the island of New Guinea are:

- Puncak Jaya, sometimes known by its former Dutch name Carstensz Pyramid, is a mist-covered limestone mountain peak on the Indonesian side of the border. At 4,884 metres (16,024 ft), Puncak Jaya makes New Guinea the world's fourth-highest landmass after Afro-Eurasia, America and Antarctica.

- Puncak Mandala, also located in Papua, is the second-highest peak on the island at 4,760 metres (15,617 ft).

- Puncak Trikora, also in Papua, is 4,750 metres (15,584 ft).

- Mount Wilhelm is the highest peak on the PNG side of the border at 4,509 metres (14,793 ft). Its granite peak is the highest point of the Bismarck Range.

- Mount Giluwe 4,368 metres (14,331 ft) is the second-highest summit in PNG. It is also the highest volcanic peak in Oceania.

Another major habitat feature is the vast southern and northern lowlands. Stretching for hundreds of kilometres, these include lowland rainforests, extensive wetlands, savanna grasslands, and some of the largest expanses of mangrove forest in the world. The southern lowlands are the site of Lorentz National Park, also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The northern lowlands are drained principally by the Mamberamo River and its tributaries on the Indonesian side, and by the Sepik on the PNG side; the more extensive southern lowlands by a larger number of rivers, principally the Digul on the Indonesian side and the Fly on the PNG side. These are the island's major river systems, draining roughly northwest, northeast, southwest, and southeast, respectively. Many have broad areas of meander and result in large areas of lakes and freshwater swamps. The largest island offshore, Dolak (Frederik Hendrik, Yos Sudarso), lies near the Digul estuary, separated by a strait so narrow it has been named a "creek".

New Guinea contains many of the world’s ecosystem types: glacial, alpine tundra, savanna, montane and lowland rainforest, mangroves, wetlands, lake and river ecosystems, seagrasses, and some of the richest coral reefs on the planet.

Relation to surroundings

The island of New Guinea lies to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago.[7] Geologically it is a part of the same tectonic plate as Australia. When world sea levels were low, the two shared shorelines (which now lie 100 to 140 metres below sea level),[8] and combined with lands now inundated into the tectonic continent of Sahul,[9][10] also known as Greater Australia.[11] The two landmasses became separated when the area now known as the Torres Strait flooded after the end of the last glacial period.Anthropologically, New Guinea is considered part of Melanesia.[12]

New Guinea is differentiated from its drier, flatter,[13] and less fertile[14][15] southern counterpart, Australia, by its much higher rainfall and its active volcanic geology, with its highest point, Puncak Jaya, reaching an elevation of 4,884 m (16,023 ft). Yet the two land masses share a similar animal fauna, with marsupials, including wallabies and possums, and the egg-laying monotreme, the echidna. Other than bats and some two dozen indigenous rodent genera,[16] there are no pre-human indigenous placental mammals. Pigs, several additional species of rats, and the ancestor of the New Guinea singing dog were introduced with human colonization.

Prior to the 1970s, archaeologists called the single Pleistocene landmass by the name Australasia,[9] although this word is most often used for a wider region that includes lands, such as New Zealand, which are not on the same continental shelf. In the early 1970s, they introduced the term Greater Australia for the Pleistocene continent.[9] Then, at a 1975 conference and consequent publication,[10] they extended the name Sahul from its previous use for just the Sahul Shelf to cover the continent.[9]

Human presence

The human presence on the island dates back at least 40,000 years, to the oldest homo sapiens migrations out of Africa. Research indicates that the highlands were an early and independent center of agriculture, with evidence of irrigation going back at least 10,000 years.[17] Because of the time depth of its inhabitation and its highly fractured landscape, an unusually high number of languages are spoken on the island, with some 1,000 languages (a figure higher than that of most continents) having been catalogued out of an estimated worldwide pre-Columbian total of more than 7,000 currently spoken human languages according to Ethnologue. Most are classified as Papuan languages, a generally accepted geographical term. A number of Austronesian languages are spoken on the coast and on offshore islands.In the 16th century, Spanish explorers arrived at the island and called it Nueva Guinea. In recent history, western New Guinea was included in the Dutch East Indies colony. The Germans annexed the northern coast of the eastern half of the island as German New Guinea in their pre–World War I effort to establish themselves as a colonial power, whilst the southeastern portion was reluctantly claimed by Britain. Following the Treaty of Versailles, the German portion was awarded to Australia (which was already governing the British claim, named the Territory of Papua) as a League of Nations mandate. The eastern half of the island was granted independence from Australia in 1975, as Papua New Guinea. The western half gained independence from the Dutch in 1961, but became part of Indonesia soon afterwards in controversial circumstances.[18]

Political divisions

Political divisions of New Guinea

The island of New Guinea is divided politically into roughly equal halves across a north-south line:

- The western portion of the island located west of 141°E longitude (except for a small section of territory to the east of the Fly River which belongs to Papua New Guinea) was formerly a Dutch colony, part of the Dutch East Indies. After the Dutch New Guinea Dispute it is now two Indonesian provinces:

- West Papua with Manokwari as its capital.

- Papua with the city of Jayapura as its capital.

- The eastern part forms the mainland of Papua New Guinea, which has been an independent country since 1975. It was formerly the Territory of Papua and New Guinea governed by Australia, consisting of the Trust Territory of New Guinea (northeastern quarter, formerly German New Guinea), and the Territory of Papua (southeastern quarter). The country consists of four regions:

- Papua, consisting of Western, Gulf, Central, Oro (Northern) and Milne Bay provinces.

- Highlands, consisting of Southern Highlands, Hela Province, Jiwaka Province, Enga Province, Western Highlands, Simbu and Eastern Highlands provinces.

- Momase, consisting of Morobe, Madang, East Sepik and Sandaun (West Sepik) provinces.

- Islands, consisting of Manus, West New Britain, East New Britain and New Ireland provinces, and the Bougainville Autonomous Province.

People

Dani tribesman in the Baliem Valley

The current population of the island of New Guinea is about eleven million. Many believe human habitation on the island dates to as early as 50,000 BC,[19] and first settlement possibly dating back to 60,000 years ago has been proposed. The island is presently populated by almost a thousand different tribal groups and a near-equivalent number of separate languages, which makes New Guinea the most linguistically diverse area in the world. Ethnologue's 14th edition lists 826 languages of Papua New Guinea and 257 languages of Irian Jaya, total 1073 languages, with 12 languages overlapping. They fall into one of two groups, the Papuan languages and the Austronesian languages.

The separation was not merely linguistic; warfare among societies was a factor in the evolution of the men's house: separate housing of groups of adult men, from the single-family houses of the women and children, for mutual protection from other tribal groups. Pig-based trade between the groups and pig-based feasts are a common theme with the other peoples of southeast Asia and Oceania. Most societies practice agriculture, supplemented by hunting and gathering.

Kurulu Village War Chief at Baliem Valley

The great variety of the island's indigenous populations are frequently assigned to one of two main ethnological divisions, based on archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence: the Papuan and Austronesian groups.[20]

Current evidence indicates that the Papuans (who constitute the majority of the island's peoples) are descended from the earliest human inhabitants of New Guinea. These original inhabitants first arrived in New Guinea at a time (either side of the Last Glacial Maximum, approx 21,000 years ago) when the island was connected to the Australian continent via a land bridge, forming the landmass known as Sahul. These peoples had made the (shortened) sea-crossing from the islands of Wallacea and Sundaland (the present Malay Archipelago) by at least 40,000 years ago, subsequent to the dispersal of peoples from Africa (circa) 50,000 – 70,000 years ago.[citation needed]

Korowai tribesman

The ancestral Austronesian peoples are believed to have arrived considerably later, approximately 3,500 years ago, as part of a gradual seafaring migration from Southeast Asia, possibly originating in Taiwan. Austronesian-speaking peoples colonized many of the offshore islands to the north and east of New Guinea, such as New Ireland and New Britain, with settlements also on the coastal fringes of the main island in places. Human habitation of New Guinea over tens of thousands of years has led to a great deal of diversity, which was further increased by the later arrival of the Austronesians and the more recent history of European and Asian settlement through events like transmigration. About half of the 2.4 million inhabitants of Indonesian Papua are Javanese migrants.[21]

Large areas of New Guinea are yet to be explored by scientists and anthropologists. The Indonesian province of West Papua is home to an estimated 44 uncontacted tribal groups.[22]

Biodiversity and ecology

With some 786,000 km2 of tropical land—less than one-half of one percent (0.5%) of the Earth's surface—New Guinea has an immense biodiversity, containing between 5 and 10 percent of the total species on the planet. This percentage is about the same amount as that found in the United States or Australia. A high percentage of New Guinea's species are endemic, and thousands are still unknown to science: probably well over 200,000 species of insect, between 11,000 and 20,000 plant species, and over 650 resident bird species. Most of these species are shared, at least in their origin, with the continent of Australia, which was until fairly recent geological times part of the same landmass (see Australia-New Guinea for an overview). The island is so large that it is considered 'nearly a continent' in terms of its biological distinctiveness.In the period from 1998 to 2008, conservationists identified 1,060 new species in New Guinea, including 218 plants, 43 reptiles, 12 mammals, 580 invertebrates, 134 amphibians, 2 birds and 71 fish.[23]

The raggiana bird-of-paradise is native to New Guinea.

The floristic region of Malesia

Biogeographically, New Guinea is part of Australasia rather than the Indomalayan realm, although New Guinea's flora has many more affinities with Asia than its fauna, which is overwhelmingly Australian. Botanically, New Guinea is considered part of Malesia, a floristic region that extends from the Malay Peninsula across Indonesia to New Guinea and the East Melanesian Islands. The flora of New Guinea is a mixture of many tropical rainforest species with origins in Asia, together with typically Australasian flora. Typical Southern Hemisphere flora include the conifers Podocarpus and the rainforest emergents Araucaria and Agathis, as well as tree ferns and several species of Eucalyptus.

New Guinea has 284 species and six orders of mammals: monotremes, three orders of marsupials, rodents and bats; 195 of the mammal species (69%) are endemic. New Guinea has 578 species of breeding birds, of which 324 species are endemic. The island's frogs are one of the most poorly known vertebrate groups, totalling 282 species, but this number is expected to double or even triple when all species have been documented. New Guinea has a rich diversity of coral life and 1,200 species of fish have been found. Also about 600 species of reef-building coral—the latter equal to 75 percent of the world’s known total. The entire coral area covers 18 million hectares off a peninsula in northwest New Guinea.

Ecoregions

Terrestrial

According to the WWF, New Guinea can be divided into twelve terrestrial ecoregions:[24]- Central Range montane rain forests

- Central Range sub-alpine grasslands

- Huon Peninsula montane rain forests

- New Guinea mangroves

- Northern New Guinea lowland rain and freshwater swamp forests

- Northern New Guinea montane rain forests

- Southeastern Papuan rain forests

- Southern New Guinea freshwater swamp forests

- Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests

- Trans Fly savanna and grasslands

- Vogelkop montane rain forests

- Vogelkop-Aru lowland rain forests

Coral reefs in Papua New Guinea

Freshwater

The WWF and Nature Conservancy divide New Guinea into five freshwater ecoregions:[25]- Vogelkop–Bomberai

- New Guinea North Coast

- New Guinea Central Mountains

- Southwest New Guinea–Trans-Fly Lowland

- Papuan Peninsula

Marine

The WWF and Nature Conservancy identify several marine ecoregions in the seas bordering New Guinea:[26]- Papua

- Bismarck Sea

- Solomon Sea

- Southeast Papua New Guinea

- Gulf of Papua

- Arafura Sea

History

Early history

The continent of Sahul before the rising ocean sundered Australia and New Guinea after the last ice age.

The first inhabitants of New Guinea arrived at least 50,000 years ago, having travelled through the south-east Asian peninsula. These first inhabitants, from whom the Papuan people are probably descended, adapted to the range of ecologies and, in time, developed one of the earliest known agricultures. Remains of this agricultural system, in the form of ancient irrigation systems in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, are being studied by archaeologists. This work is still in its early stages, so there is still uncertainty as to precisely what crop was being grown, or when/where agriculture arose. Sugar cane was cultivated for the first time in New Guinea around 6000 BC.[27]

The gardens of the New Guinea Highlands are ancient, intensive permacultures, adapted to high population densities, very high rainfalls (as high as 10,000 mm/yr (400 in/yr)), earthquakes, hilly land, and occasional frost. Complex mulches, crop rotations and tillages are used in rotation on terraces with complex irrigation systems. Western agronomists still do not understand all of the practices, and it has been noted that native gardeners are as, or even more, successful than most scientific farmers in raising certain crops.[28] There is evidence that New Guinea gardeners invented crop rotation well before western Europeans.[29] A unique feature of New Guinea permaculture is the silviculture of Casuarina oligodon, a tall, sturdy native ironwood tree, suited to use for timber and fuel, with root nodules that fix nitrogen. Pollen studies show that it was adopted during an ancient period of extreme deforestation.

In more recent millennia, another wave of people arrived on the shores of New Guinea. These were the Austronesian people, who had spread down from Taiwan, through the South-east Asian archipelago, colonising many of the islands on the way. The Austronesian people had technology and skills extremely well adapted to ocean voyaging and Austronesian language speaking people are present along much of the coastal areas and islands of New Guinea. These Austronesian migrants are considered the ancestors of most people in insular Southeast Asia, from Sumatra and Java to Borneo and Sulawesi, as well as coastal new Guinea.[30]

Precolonial history

Group of natives at Mairy Pass. Mainland of British New Guinea in 1885.

Papuans on the Lorentz River, photographed during the third South New Guinea expedition in 1912–13.

The western part of the island was in contact with kingdoms in other parts of modern-day Indonesia. The Negarakertagama mentioned the region of Wanin in eastern Nusantara as part of Majapahit's tributary. This has been identified with the Onin Peninsula, part of the Bomberai Peninsula near the city of Fakfak.[31][32] The sultans of Tidore, in Maluku Islands, claimed sovereignty over various coastal parts of the island.[33] During Tidore's rule, the main exports of the island during this period were resins, spices, slaves and the highly priced feathers of the bird-of-paradise.[33] Sultan Nuku, one of the most famous Tidore sultans who rebelled against Dutch colonization, called himself "Sultan of Tidore and Papua",[34] during his revolt in 1780s. He commanded loyalty from both Moluccan and Papuan chiefs, especially those of Raja Ampat Islands. Following Tidore's defeat, much of the territory it claimed in western part of New Guinea came under Dutch rule as part of Dutch East Indies.[34]

European contact

The first European contact with New Guinea was by Portuguese and Spanish sailors in the 16th century. In 1526–27, the Portuguese explorer Jorge de Meneses saw the western tip of New Guinea and named it ilhas dos Papuas. In 1528, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Saavedra also recorded its sighting when trying to return from Tidore to New Spain. In 1545, the Spaniard Íñigo Ortíz de Retes sailed along the north coast of New Guinea as far as the Mamberamo River, near which he landed on 20 June, naming the island 'Nueva Guinea'.[35] The first map showing the whole island (as an island) was published in 1600 and shows it as 'Nova Guinea'. In 1606, Luís Vaz de Torres explored the southern coast of New Guinea from Milne Bay to the Gulf of Papua including Orangerie Bay, which he named Bahía de San Lorenzo. His expedition also discovered Basilaki Island naming it Tierra de San Buenaventura, which he claimed for Spain in July 1606.[36] On 18 October, his expedition reached the western part of the island in present-day Indonesia, and also claimed the territory for the King of Spain.

New Guinea from 1884 to 1919. The Netherlands controlled the western half of New Guinea, Germany the north-eastern part, and Britain the south-eastern part.

A successive European claim occurred in 1828, when the Netherlands formally claimed the western half of the island as Netherlands New Guinea. In 1883, following a short-lived French annexation of New Ireland, the British colony of Queensland annexed south-eastern New Guinea. However, the Queensland government's superiors in the United Kingdom revoked the claim, and (formally) assumed direct responsibility in 1884, when Germany claimed north-eastern New Guinea as the protectorate of German New Guinea (also called Kaiser-Wilhelmsland).

The first Dutch government posts were established in 1898 and in 1902: Manokwari on the north coast, Fak-Fak in the west and Merauke in the south at the border with British New Guinea. The German, Dutch and British colonial administrators each attempted to suppress the still-widespread practices of inter-village warfare and headhunting within their respective territories.[37]

In 1905, the British government transferred some administrative responsibility over southeast New Guinea to Australia (which renamed the area "Territory of Papua"); and, in 1906, transferred all remaining responsibility to Australia. During World War I, Australian forces seized German New Guinea, which in 1920 became the Territory of New Guinea, to be administered by Australia under a League of Nations mandate. The territories under Australian administration became collectively known as The Territories of Papua and New Guinea (until February 1942).

Before about 1930, European maps showed the highlands as uninhabited forests.[citation needed] When first flown over by aircraft, numerous settlements with agricultural terraces and stockades were observed. The most startling discovery took place on 4 August 1938, when Richard Archbold discovered the Grand Valley of the Baliem River, which had 50,000 yet-undiscovered Stone Age farmers living in orderly villages. The people, known as the Dani, were the last society of its size to make first contact with the rest of the world.[38]

World War II

Australian soldiers resting in the Finisterre Ranges of New Guinea while en route to the front line

Netherlands New Guinea and the Australian territories were invaded in 1942 by the Japanese. The Australian territories were put under military administration and were known simply as New Guinea. The highlands, northern and eastern parts of the island became key battlefields in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. Papuans often gave vital assistance to the Allies, fighting alongside Australian troops, and carrying equipment and injured men across New Guinea. Approximately 216,000 Japanese, Australian and U.S. soldiers, sailors and airmen died during the New Guinea Campaign.[39]

Since World War II

Following the return to civil administration after WW2, the Australian section was known as the Territory of Papua-New Guinea from 1945 to 1949 and then as Territory of Papua and New Guinea. Although the rest of the Dutch East Indies achieved independence as Indonesia on 27 December 1949, the Netherlands regained control of western New Guinea.

Map of New Guinea, with place names as used in English in the 1940s

During the 1950s, the Dutch government began to prepare Netherlands New Guinea for full independence and allowed elections in 1959; the elected New Guinea Council took office on 5 April 1961. The Council decided on the name of West Papua for the territory, along with an emblem, flag, and anthem to complement those of the Netherlands. On 1 October 1962, the Dutch handed over the territory to the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority, until 1 May 1963, when Indonesia took control. The territory was renamed West Irian and then Irian Jaya. In 1969, Indonesia, under the 1962 New York Agreement, organised a referendum named the Act of Free Choice, in which hand picked Papuan tribal elders reached a consensus to continue the union with Indonesia.[citation needed]

There has been resistance to Indonesian integration and occupation,[21] both through civil disobedience (such as Morning Star flag raising ceremonies) and via the formation of the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM, or Free Papua Movement) in 1965. Amnesty International has estimated more than 100,000 Papuans, one-sixth of the population, have died as a result of government-sponsored violence against West Papuans.[40]

Western New Guinea was formally annexed by Indonesia in 1969

From 1971, the name Papua New Guinea was used for the Australian territory. On 16 September 1975, Australia granted full independence to Papua New Guinea.

In 2000, Irian Jaya was formally renamed "The Province of Papua" and a Law on Special Autonomy was passed in 2001. The Law established a Papuan People's Assembly (MRP) with representatives of the different indigenous cultures of Papua. The MRP was empowered to protect the rights of Papuans, raise the status of women in Papua, and to ease religious tensions in Papua; block grants were given for the implementation of the Law as much as $266 million in 2004.[41] The Indonesian courts' enforcement of the Law on Special Autonomy blocked further creation of subdivisions of Papua: although President Megawati Sukarnoputri was able to create a separate West Papua province in 2003 as a fait accompli, plans for a third province on western New Guinea were blocked by the courts.[42] Critics argue that the Indonesian government has been reluctant to establish or issue various government implementing regulations so that the legal provisions of special autonomy could be put into practice, and as a result special autonomy in Papua has failed.