Natural resource management refers to the management of natural resources such as land, water, soil, plants and animals, with a particular focus on how management affects the quality of life for both present and future generations (stewardship).

Natural resource management deals with managing the way in which people and natural landscapes interact. It brings together land use planning, water management, biodiversity conservation, and the future sustainability of industries like agriculture, mining, tourism, fisheries and forestry. It recognises that people and their livelihoods rely on the health and productivity of our landscapes, and their actions as stewards of the land play a critical role in maintaining this health and productivity.

Natural resource management specifically focuses on a scientific and technical understanding of resources and ecology and the life-supporting capacity of those resources. Environmental management is also similar to natural resource management. In academic contexts, the sociology of natural resources is closely related to, but distinct from, natural resource management.

History

The Bureau of Land Management in the United States manages America's public lands, totaling approximately 264 million acres (1,070,000 km2) or one-eighth of the landmass of the country.

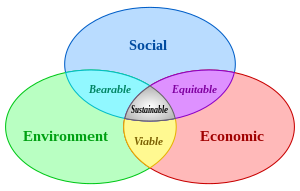

The emphasis on sustainability can be traced back to early attempts to understand the ecological nature of North American rangelands in the late 19th century, and the resource conservation movement of the same time. This type of analysis coalesced in the 20th century with recognition that preservationist conservation strategies had not been effective in halting the decline of natural resources. A more integrated approach was implemented recognising the intertwined social, cultural, economic and political aspects of resource management. A more holistic, national and even global form evolved, from the Brundtland Commission and the advocacy of sustainable development.

In 2005 the government of New South Wales, established a Standard for Quality Natural Resource Management, to improve the consistency of practice, based on an adaptive management approach.

In the United States, the most active areas of natural resource management are wildlife management often associated with ecotourism and rangeland management. In Australia, water sharing, such as the Murray Darling Basin Plan and catchment management are also significant.

Ownership regimes

Natural resource management approaches can be categorised according to the kind and right of stakeholders, natural resources:- State property: Ownership and control over the use of resources is in hands of the state. Individuals or groups may be able to make use of the resources, but only at the permission of the state. National forest, National parks and military reservations are some US examples.

- Private property: Any property owned by a defined individual or corporate entity. Both the benefit and duties to the resources fall to the owner(s). Private land is the most common example.

- Common property: It is a private property of a group. The group may vary in size, nature and internal structure e.g. indigenous neighbours of village. Some examples of common property are community forests.

- Non-property (open access): There is no definite owner of these properties. Each potential user has equal ability to use it as they wish. These areas are the most exploited. It is said that "Everybody's property is nobody's property". An example is a lake fishery. Common land may exist without ownership, in which case in the UK it is vested in a local authority.

- Hybrid: Many ownership regimes governing natural resources will contain parts of more than one of the regimes described above, so natural resource managers need to consider the impact of hybrid regimes. An example of such a hybrid is native vegetation management in NSW, Australia, where legislation recognises a public interest in the preservation of native vegetation, but where most native vegetation exists on private land.

Stakeholder analysis

Stakeholder analysis originated from business management practices and has been incorporated into natural resource management in ever growing popularity. Stakeholder analysis in the context of natural resource management identifies distinctive interest groups affected in the utilisation and conservation of natural resources.There is no definitive definition of a stakeholder as illustrated in the table below. Especially in natural resource management as it is difficult to determine who has a stake and this will differ according to each potential stakeholder.

Different approaches to who is a stakeholder:

| Source | Who is a stakeholder | Kind of research |

|---|---|---|

| Freeman. | ‘‘can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objectives’’ | Business Management |

| Bowie | ‘‘without whose support the organization would cease to exist’’ | Business Management |

| Clarkson | ‘‘...persons or groups that have, or claim, ownership, rights, or interests in a corporation and its activities, past, present, or future.’’ | Business Management |

| Grimble and Wellard | ‘‘...any group of people, organized or unorganized, who share a common interest or stake in a particular issue or system...’’ | Natural resource

management

|

| Gass et al. | ‘‘...any individual, group and institution who would potentially be affected, whether positively or negatively, by a specified event, process or change.’’ | Natural resource

management

|

| Buanes et al | ‘‘...any group or individual who may directly or indirectly affect—or be affected—...planning to be at least potential stakeholders.’’ | Natural resource

management

|

| Brugha and Varvasovszky | ‘‘...actors who have an interest in the issue under consideration, who are affected by the issue, or who—because of their position—have or could have an active or passive influence on the decision making and implementation process.’’ | Health policy |

| ODA | ‘‘... persons, groups or institutions with interests in a project or programme.’’ | Development |

Therefore, it is dependent upon the circumstances of the stakeholders involved with natural resource as to which definition and subsequent theory is utilised.

Billgrena and Holme identified the aims of stakeholder analysis in natural resource management:

- Identify and categorise the stakeholders that may have influence

- Develop an understanding of why changes occur

- Establish who can make changes happen

- How to best manage natural resources

Stages in Stakeholder analysis:

- Clarify objectives of the analysis

- Place issues in a systems context

- Identify decision-makers and stakeholders

- Investigate stakeholder interests and agendas

- Investigate patterns of inter-action and dependence (e.g. conflicts and compatibilities, trade-offs and synergies)

Grimble and Wellard established that Stakeholder analysis in natural resource management is most relevant where issued can be characterised as;

- Cross-cutting systems and stakeholder interests

- Multiple uses and users of the resource.

- Market failure

- Subtractability and temporal trade-offs

- Unclear or open-access property rights

- Untraded products and services

- Poverty and under-representation

In the case of the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, a comprehensive stakeholder analysis would have been relevant and the Batwa people would have potentially been acknowledged as stakeholders preventing the loss of people's livelihoods and loss of life.

Nepal, Indonesia and Koreas' community forestry are successful examples of how stakeholder analysis can be incorporated into the management of natural resources. This allowed the stakeholders to identify their needs and level of involvement with the forests.

Criticisms:

- Natural resource management stakeholder analysis tends to include too many stakeholders which can create problems in of its self as suggested by Clarkson. ‘‘Stakeholder theory should not be used to weave a basket big enough to hold the world's misery.’’

- Starik proposed that nature needs to be represented as stakeholder. However this has been rejected by many scholars as it would be difficult to find appropriate representation and this representation could also be disputed by other stakeholders causing further issues.

- Stakeholder analysis can be used exploited and abused in order to marginalise other stakeholders.

- Identifying the relevant stakeholders for participatory processes is complex as certain stakeholder groups may have been excluded from previous decisions.

- On-going conflicts and lack of trust between stakeholders can prevent compromise and resolutions.

Management of the resources

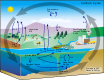

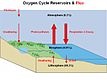

Natural resource management issues are inherently complex. They involve the ecological cycles, hydrological cycles, climate, animals, plants and geography, etc. All these are dynamic and inter-related. A change in one of them may have far reaching and/or long term impacts which may even be irreversible. In addition to the natural systems, natural resource management also has to manage various stakeholders and their interests, policies, politics, geographical boundaries, economic implications and the list goes on. It is a very difficult to satisfy all aspects at the same time. This results in conflicting situations.After the United Nations Conference for the Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, most nations subscribed to new principles for the integrated management of land, water, and forests. Although program names vary from nation to nation, all express similar aims.

The various approaches applied to natural resource management include:

- Top-down (command and control)

- Community-based natural resource management

- Adaptive management

- Precautionary approach

- Integrated natural resource management

Community-based natural resource management

The community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) approach combines conservation objectives with the generation of economic benefits for rural communities. The three key assumptions being that: locals are better placed to conserve natural resources, people will conserve a resource only if benefits exceed the costs of conservation, and people will conserve a resource that is linked directly to their quality of life. When a local people's quality of life is enhanced, their efforts and commitment to ensure the future well-being of the resource are also enhanced. Regional and community based natural resource management is also based on the principle of subsidiarity.The United Nations advocates CBNRM in the Convention on Biodiversity and the Convention to Combat Desertification. Unless clearly defined, decentralised NRM can result an ambiguous socio-legal environment with local communities racing to exploit natural resources while they can e.g. forest communities in central Kalimantan (Indonesia).

A problem of CBNRM is the difficulty of reconciling and harmonising the objectives of socioeconomic development, biodiversity protection and sustainable resource utilisation. The concept and conflicting interests of CBNRM, show how the motives behind the participation are differentiated as either people-centred (active or participatory results that are truly empowering) or planner-centred (nominal and results in passive recipients). Understanding power relations is crucial to the success of community based NRM. Locals may be reluctant to challenge government recommendations for fear of losing promised benefits.

CBNRM is based particularly on advocacy by nongovernmental organizations working with local groups and communities, on the one hand, and national and transnational organizations, on the other, to build and extend new versions of environmental and social advocacy that link social justice and environmental management agendas with both direct and indirect benefits observed including a share of revenues, employment, diversification of livelihoods and increased pride and identity. Ecological and societal successes and failures of CBNRM projects have been documented. CBNRM has raised new challenges, as concepts of community, territory, conservation, and indigenous are worked into politically varied plans and programs in disparate sites. Warner and Jones address strategies for effectively managing conflict in CBNRM.

The capacity of indigenous communities to conserve natural resources has been acknowledged by the Australian Government with the Caring for Country Program. Caring for our Country is an Australian Government initiative jointly administered by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. These Departments share responsibility for delivery of the Australian Government's environment and sustainable agriculture programs, which have traditionally been broadly referred to under the banner of ‘natural resource management’. These programs have been delivered regionally, through 56 State government bodies, successfully allowing regional communities to decide the natural resource priorities for their regions.

More broadly, a research study based in Tanzania and the Pacific researched what motivates communities to adopt CBNRM's and found that aspects of the specific CBNRM program, of the community that has adopted the program, and of the broader social-ecological context together shape the why CBNRM's are adopted. However, overall, program adoption seemed to mirror the relative advantage of CBNRM programs to local villagers and villager access to external technical assistance. There have been socioeconomic critiques of CBNRM in Africa, but ecological effectiveness of CBNRM measured by wildlife population densities has been shown repeatedly in Tanzania.

Governance is seen as a key consideration for delivering community-based or regional natural resource management. In the State of NSW, the 13 catchment management authorities (CMAs) are overseen by the Natural Resources Commission (NRC), responsible for undertaking audits of the effectiveness of regional natural resource management programs.

Adaptive management

The primary methodological approach adopted by catchment management authorities (CMAs) for regional natural resource management in Australia is adaptive management.This approach includes recognition that adaption occurs through a process of ‘plan-do-review-act’. It also recognises seven key components that should be considered for quality natural resource management practice:

- Determination of scale

- Collection and use of knowledge

- Information management

- Monitoring and evaluation

- Risk management

- Community engagement

- Opportunities for collaboration.

Integrated natural resource management

Integrated natural resource management (INRM) is a process of managing natural resources in a systematic way, which includes multiple aspects of natural resource use (biophysical, socio-political, and economic) meet production goals of producers and other direct users (e.g., food security, profitability, risk aversion) as well as goals of the wider community (e.g., poverty alleviation, welfare of future generations, environmental conservation). It focuses on sustainability and at the same time tries to incorporate all possible stakeholders from the planning level itself, reducing possible future conflicts. The conceptual basis of INRM has evolved in recent years through the convergence of research in diverse areas such as sustainable land use, participatory planning, integrated watershed management, and adaptive management. INRM is being used extensively and been successful in regional and community based natural management.Frameworks and modelling

There are various frameworks and computer models developed to assist natural resource management.Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

GIS is a powerful analytical tool as it is capable of overlaying datasets to identify links. A bush regeneration scheme can be informed by the overlay of rainfall, cleared land and erosion. In Australia, Metadata Directories such as NDAR provide data on Australian natural resources such as vegetation, fisheries, soils and water. These are limited by the potential for subjective input and data manipulation.

Natural Resources Management Audit Frameworks

The NSW Government in Australia has published an audit framework for natural resource management, to assist the establishment of a performance audit role in the governance of regional natural resource management. This audit framework builds from other established audit methodologies, including performance audit, environmental audit and internal audit. Audits undertaken using this framework have provided confidence to stakeholders, identified areas for improvement and described policy expectations for the general public.

The Australian Government has established a framework for auditing greenhouse emissions and energy reporting, which closely follows Australian Standards for Assurance Engagements.

The Australian Government is also currently preparing an audit framework for auditing water management, focussing on the implementation of the Murray Darling Basin Plan.

Other elements

- Biodiversity Conservation

- Precautionary Biodiversity Management

- Concrete "policy tools"

- Administration and guidelines

- "Ecosystem-based management" including "more risk-averse and precautionary management", where "given prevailing uncertainty regarding ecosystem structure, function, and inter-specific interactions, precaution demands an ecosystem rather than single-species approach to management".

- "Adaptive management" is "a management approach that expressly tackles the uncertainty and dynamism of complex systems".

- "Environmental impact assessment" and exposure ratings decrease the "uncertainties" of precaution, even though it has deficiencies, and

- "Protectionist approaches", which "most frequently links to" biodiversity conservation in natural resources management.

- Land management

- Comprehending the processes of nature including ecosystem, water, soils

- Using appropriate and adapting management systems in local situations

- Cooperation between scientists who have knowledge and resources and local people who have knowledge and skills

- Examine impacts of local decisions in a regional context, and the effects on natural resources.

- Plan for long-term change and unexpected events.

- Preserve rare landscape elements and associated species.

- Avoid land uses that deplete natural resources.

- Retain large contiguous or connected areas that contain critical habitats.

- Minimize the introduction and spread of non-native species.

- Avoid or compensate for the effects of development on ecological processes.

- Implement land-use and land-management practices that are compatible with the natural potential of the area.