| Spina bifida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of a child with spina bifida | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, neurosurgery, rehabilitation medicine |

| Symptoms | Hairy patch, dimple, dark spot, swelling on the lower back |

| Complications | Poor ability to walk, problems with bladder or bowel control, hydrocephalus, tethered spinal cord, latex allergy |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors |

| Risk factors | Lack of folate during pregnancy, certain antiseizure medications, obesity, poorly controlled diabetes |

| Diagnostic method | Amniocentesis, medical imaging |

| Prevention | Folate supplementation |

| Treatment | Surgery |

| Frequency | 15% (occulta), 0.1–5 per 1000 births (others) |

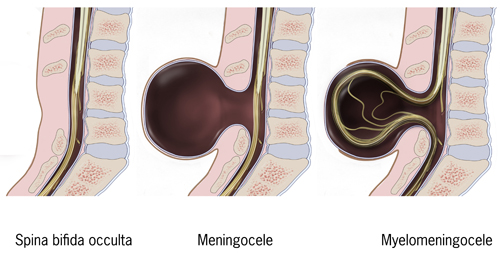

Spina bifida is a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and membranes around the spinal cord during early development in pregnancy. There are three main types: spina bifida occulta, meningocele and myelomeningocele. The most common location is the lower back, but in rare cases it may be the middle back or neck. Occulta has no or only mild signs, which may include a hairy patch, dimple, dark spot or swelling on the back at the site of the gap in the spine. Meningocele typically causes mild problems with a sac of fluid present at the gap in the spine. Myelomeningocele, also known as open spina bifida, is the most severe form. Associated problems include poor ability to walk, problems with bladder or bowel control, accumulation of fluid in the brain (hydrocephalus), a tethered spinal cord and latex allergy. Learning problems are relatively uncommon.

Spina bifida is believed to be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. After having one child with the condition, or if one of the parents has the condition, there is a 4% chance that the next child will also be affected. Not having enough folate in the diet before and during pregnancy also plays a significant role. Other risk factors include certain antiseizure medications, obesity and poorly controlled diabetes. Diagnosis may occur either before or after a child is born. Before birth, if a blood test or amniocentesis finds a high level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), there is a higher risk of spina bifida. Ultrasound examination may also detect the problem. Medical imaging can confirm the diagnosis after birth. Spina bifida is a type of neural tube defect related to but distinct from other types such as anencephaly and encephalocele.

Most cases of spina bifida can be prevented if the mother gets enough folate before and during pregnancy. Adding folic acid to flour has been found to be effective for most women. Open spina bifida can be surgically closed before or after birth. A shunt may be needed in those with hydrocephalus, and a tethered spinal cord may be surgically repaired. Devices to help with movement such as crutches or wheelchairs may be useful. Urinary catheterization may also be needed.

About 15% of people have spina bifida occulta. Rates of other types of spina bifida vary significantly by country, from 0.1 to 5 per 1,000 births. On average, in developed countries, including the United States, it occurs in about 0.4 per 1,000 births. In India, it affects about 1.9 per 1,000 births. Caucasians are at higher risk compared to Black people. The term is Latin for "split spine".

Types

Different types of spina bifida

There are two types: spina bifida occulta and spina bifida cystica. Spina bifida cystica can then be broken down into meningocele and myelomeningocele.

Spina bifida occulta

Occulta is Latin for "hidden". This is the mildest form of spina bifida.

In occulta, the outer part of some of the vertebrae is not completely closed. The splits in the vertebrae are so small that the spinal cord does not protrude. The skin at the site of the lesion may be normal, or it may have some hair growing from it; there may be a dimple in the skin, or a birthmark. Unlike most other types of neural tube defects, spina bifida occulta is not associated with increased AFP,

a common screening tool used to detect neural tube defects in utero.

This is because, unlike most of the other neural tube defects, the dural

lining is maintained.

Many people with this type of spina bifida do not even know they have it, as the condition is asymptomatic in most cases. About 15% of people have spina bifida occulta, and most people are diagnosed incidentally from spinal X-rays.

A systematic review of radiographic research studies found no relationship between spina bifida occulta and back pain. More recent studies not included in the review support the negative findings.

However, other studies suggest spina bifida occulta is not always

harmless. One study found that among patients with back pain, severity

is worse if spina bifida occulta is present.

Among females, this could be mistaken for dysmenorrhea.

Incomplete posterior fusion is not a true spina bifida, and is very rarely of neurological significance.

Meningocele

A posterior meningocele (/mɪˈnɪŋɡəˌsiːl/) or meningeal cyst (/mɪˈnɪndʒiəl/) is the least common form of spina bifida. In this form, a single developmental defect allows the meninges

to herniate between the vertebrae. As the nervous system remains

undamaged, individuals with meningocele are unlikely to suffer long-term

health problems, although cases of tethered cord have been reported. Causes of meningocele include teratoma and other tumors of the sacrococcyx and of the presacral space, and Currarino syndrome.

A meningocele may also form through dehiscences in the base of

the skull. These may be classified by their localisation to occipital,

frontoethmoidal, or nasal. Endonasal meningoceles lie at the roof of the

nasal cavity and may be mistaken for a nasal polyp. They are treated surgically. Encephalomeningoceles are classified in the same way and also contain brain tissue.

Myelomeningocele

A lumbar myelomeningocele

Myelomeningocele (MMC), also known as meningomyelocele, is the type

of spina bifida that often results in the most severe complications and

affects the meninges and nerves.

In individuals with myelomeningocele, the unfused portion of the spinal

column allows the spinal cord to protrude through an opening.

Myelomeningocele occurs in the third week of embryonic development,

during neural tube pore closure. MMC is a failure of this to occur

completely.

The meningeal membranes that cover the spinal cord also protrude

through the opening, forming a sac enclosing the spinal elements, such

as meninges, cerebrospinal fluid, and parts of the spinal cord and nerve

roots. Myelomeningocele is also associated with Arnold–Chiari malformation, necessitating a VP shunt placement.

Toxins associated with MMC formation include: calcium-channel blockers, carbamazepine, cytochalasins, hyperthermia, and valproic acid.

Myelocele

Spina

bifida with myelocele is the most severe form of myelomeningocele. In

this type, the involved area is represented by a flattened, plate-like

mass of nervous tissue with no overlying membrane. The exposure of these

nerves and tissues make the baby more prone to life-threatening

infections such as meningitis.

The protruding portion of the spinal cord and the nerves that

originate at that level of the cord are damaged or not properly

developed. As a result, there is usually some degree of paralysis

and loss of sensation below the level of the spinal cord defect. Thus,

the more cranial the level of the defect, the more severe the associated

nerve dysfunction and resultant paralysis may be. Symptoms may include

ambulatory problems, loss of sensation, deformities of the hips, knees

or feet, and loss of muscle tone.

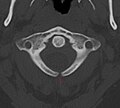

- X-ray computed tomography scan of unfused arch at C1

- Myelomeningocele in the lumbar area

(1) External sac with cerebrospinal fluid

(2) Spinal cord wedged between the vertebrae

Signs and symptoms

Physical problems

Physical signs of spina bifida may include:

- Leg weakness and paralysis

- Orthopedic abnormalities (i.e., club foot, hip dislocation, scoliosis)

- Bladder and bowel control problems, including incontinence, urinary tract infections, and poor kidney function

- Pressure sores and skin irritations

- Abnormal eye movement

68% of children with spina bifida have an allergy to latex,

ranging from mild to life-threatening. The common use of latex in

medical facilities makes this a particularly serious concern. The most

common approach to avoid developing an allergy is to avoid contact with

latex-containing products such as examination gloves and condoms and catheters that do not specify they are latex-free, and many other products, such as some commonly used by dentists.

The spinal cord lesion or the scarring due to surgery may result in a tethered spinal cord.

In some individuals, this causes significant traction and stress on the

spinal cord and can lead to a worsening of associated paralysis, scoliosis, back pain, and worsening bowel and/or bladder function.

Neurological problems

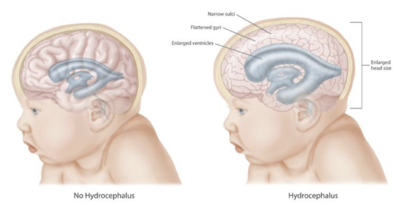

Many individuals with spina bifida have an associated abnormality of the cerebellum, called the Arnold Chiari II malformation.

In affected individuals, the back portion of the brain is displaced

from the back of the skull down into the upper neck. In about 90% of the

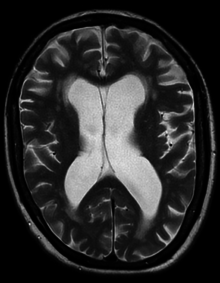

people with myelomeningocele, hydrocephalus also occurs because the displaced cerebellum interferes with the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid, causing an excess of the fluid to accumulate.

In fact, the cerebellum also tends to be smaller in individuals with

spina bifida, especially for those with higher lesion levels.

The corpus callosum

is abnormally developed in 70–90% of individuals with spina bifida

myelomeningocele; this affects the communication processes between the

left and right brain hemispheres. Further, white matter

tracts connecting posterior brain regions with anterior regions appear

less organized. White matter tracts between frontal regions have also

been found to be impaired.

Cortex abnormalities may also be present. For example, frontal regions

of the brain tend to be thicker than expected, while posterior and

parietal regions are thinner. Thinner sections of the brain are also

associated with increased cortical folding. Neurons within the cortex may also be displaced.

Executive function

Several studies have demonstrated difficulties with executive functions in youth with spina bifida, with greater deficits observed in youth with shunted hydrocephalus.

Unlike typically developing children, youths with spina bifida do not

tend to improve in their executive functioning as they grow older. Specific areas of difficulty in some individuals include planning, organizing, initiating, and working memory. Problem-solving, abstraction, and visual planning may also be impaired. Further, children with spina bifida may have poor cognitive flexibility. Although executive functions are often attributed to the frontal lobes of the brain, individuals with spina bifida have intact frontal lobes; therefore, other areas of the brain may be implicated.

Individuals with spina bifida, especially those with shunted

hydrocephalus, often have attention problems. Children with spina bifida

and shunted hydrocephalus have higher rates of ADHD than children without those conditions (31% vs. 17%).

Deficits have been observed for selective attention and focused

attention, although poor motor speed may contribute to poor scores on

tests of attention. Attention deficits may be evident at a very early age, as infants with spina bifida lag behind their peers in orienting to faces.

Academic skills

Individuals with spina bifida may struggle academically, especially in the subjects of mathematics and reading. In one study, 60% of children with spina bifida were diagnosed with a learning disability.

In addition to brain abnormalities directly related to various academic

skills, achievement is likely affected by impaired attentional control

and executive functioning. Children with spina bifida may perform well in elementary school, but begin to struggle as academic demands increase.

Children with spina bifida are more likely than their peers without spina bifida to be dyscalculic.

Individuals with spina bifida have demonstrated stable difficulties

with arithmetic accuracy and speed, mathematical problem-solving, and

general use and understanding of numbers in everyday life. Mathematics difficulties may be directly related to the thinning of the parietal lobes (regions implicated in mathematical functioning) and indirectly associated with deformities of the cerebellum and midbrain

that affect other functions involved in mathematical skills. Further,

higher numbers of shunt revisions are associated with poorer mathematics

abilities. Working memory and inhibitory control deficiencies have been implicated for math difficulties, although visual-spatial difficulties are not likely involved. Early intervention to address mathematics difficulties and associated executive functions is crucial.

Individuals with spina bifida tend to have better reading skills than mathematics skills. Children and adults with spina bifida have stronger abilities in reading accuracy than in reading comprehension.

Comprehension may be especially impaired for text that requires an

abstract synthesis of information rather than a more literal

understanding. Individuals with spina bifida may have difficulty with writing due to deficits in fine motor control and working memory.

Cause

Spina bifida is believed to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

After having one child with the condition, or if a parent has the

condition, there is a 4% chance the next child will also be affected. A folic acid deficiency during pregnancy also plays a significant role. Other risk factors include certain antiseizure medications, obesity, and poorly managed diabetes. Alcohol misuse can trigger macrocytosis which discards folate. After stopping the drinking of alcohol, a time period of months is needed to rejuvenate bone marrow and recover from the macrocytosis.

Those who are white or Hispanic have a higher risk. Girls are more prone to being born with spina bifida.

Pathophysiology

Spina

bifida occurs when local regions of the neural tube fail to fuse or

there is failure in formation of the vertebral neural arches. Neural

arch formation occurs in the first month of embryonic

development (often before the mother knows she is pregnant). Some forms

are known to occur with primary conditions that cause raised central

nervous system pressure, raising the possibility of a dual pathogenesis.

In normal circumstances, the closure of the neural tube occurs

around the 23rd (rostral closure) and 27th (caudal closure) day after fertilization.

However, if something interferes and the tube fails to close properly, a

neural tube defect will occur. Medications such as some anticonvulsants, diabetes, obesity, and having a relative with spina bifida can all affect the probability of neural tube malformation.

Extensive evidence from mouse strains with spina bifida indicates

that there is sometimes a genetic basis for the condition. Human spina

bifida, like other human diseases, such as cancer, hypertension and atherosclerosis (coronary artery disease), likely results from the interaction of multiple genes and environmental factors.

Research has shown the lack of folic acid

(folate) is a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of neural tube

defects, including spina bifida. Supplementation of the mother's diet

with folate can reduce the incidence of neural tube defects by about

70%, and can also decrease the severity of these defects when they

occur. It is unknown how or why folic acid has this effect.

Spina bifida does not follow direct patterns of heredity as do muscular dystrophy or haemophilia.

Studies show a woman having had one child with a neural tube defect

such as spina bifida has about a 3% risk of having another affected

child. This risk can be reduced with folic acid supplementation before

pregnancy. For the general population, low-dose folic acid supplements

are advised (0.4 mg/day).

Prevention

There is neither a single cause of spina bifida nor any known way to prevent it entirely. However, dietary supplementation with folic acid has been shown to be helpful in reducing the incidence of spina bifida. Sources of folic acid include whole grains, fortified breakfast cereals, dried beans, leaf vegetables and fruits. However it is difficult for women to get the recommended 400 micrograms of folic acid a day from unfortified foods.

Globally, fortified wheat flour is credited with preventing 50 thousand

neural tube birth defects like spina bifida a year, but 230,000 could

be prevented every year through this strategy.

Folate fortification of enriched grain products has been

mandatory in the United States since 1998. This prevents an estimated

600 to 700 incidents of spina bifida a year in the U.S. and saves $400 -

$600 million in healthcare expenses. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Public Health Agency of Canada

and UK recommended amount of folic acid for women of childbearing age

and women planning to become pregnant is at least 0.4 mg/day of folic

acid from at least three months before conception, and continued for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Women who have already had a baby with spina bifida or other type of neural tube defect, or are taking anticonvulsant medication, should take a higher dose of 4–5 mg/day.

Certain mutations in the gene VANGL1 have been linked with spina bifida in some families with a history of the condition.

Screening

Open spina bifida can usually be detected during pregnancy by fetal ultrasound. Increased levels of maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) should be followed up by two tests – an ultrasound of the fetal spine and amniocentesis of the mother's amniotic fluid (to test for alpha-fetoprotein and acetylcholinesterase). AFP tests are now mandated by some state laws (including California).

and failure to provide them can have legal ramifications. In one case, a

man born with spina bifida was awarded a $2-million settlement after

court found his mother's OBGYN negligent for not performing these tests. Spina bifida may be associated with other malformations as in dysmorphic syndromes, often resulting in spontaneous miscarriage. In the majority of cases, though, spina bifida is an isolated malformation.

Genetic counseling and further genetic testing,

such as amniocentesis, may be offered during the pregnancy, as some

neural tube defects are associated with genetic disorders such as trisomy 18. Ultrasound screening for spina bifida is partly responsible for the decline in new cases, because many pregnancies are terminated out of fear that a newborn might have a poor future quality of life. With modern medical care, the quality of life of patients has greatly improved.

- Ultrasound view of the fetal spine at 21 weeks of pregnancy. In the longitudinal scan a lumbar myelomeningocele is seen.

- Anatomy scan of the fetal head at 20 weeks of pregnancy in a fetus affected by spina bifida. In the axial scan the characteristic lemon sign and banana sign are seen.

Treatment

There

is no known cure for nerve damage caused by spina bifida. Standard

treatment is surgery after delivery. This surgery aims to prevent

further damage of the nervous tissue and to prevent infection; pediatric neurosurgeons operate to close the opening on the back. The spinal cord and its nerve roots are put back inside the spine and covered with meninges. In addition, a shunt

may be surgically installed to provide a continuous drain for the

excess cerebrospinal fluid produced in the brain, as happens with hydrocephalus. Shunts most commonly drain into the abdomen or chest wall.

Pregnancy

Standard

treatment is after delivery. There is tentative evidence about

treatment for severe disease before delivery while the baby is inside

the womb. As of 2014, however, the evidence remains insufficient to determine benefits and harms.

Treatment of spina bifida during pregnancy is not without risk. To the mother, this includes scarring of the uterus. To the baby, there is the risk of preterm birth.

Broadly, there are two forms of prenatal treatment. The first is

open fetal surgery, where the uterus is opened and the spina bifida

repair performed. The second is via fetoscopy. These techniques may be

an option to standard therapy.

Childhood

Most individuals with myelomeningocele will need periodic evaluations by a variety of specialists:

- Physiatrists coordinate the rehabilitation efforts of different therapists and prescribe specific therapies, adaptive equipment, or medications to encourage as high of a functional performance within the community as possible.

- Orthopedists monitor growth and development of bones, muscles, and joints.

- Neurosurgeons perform surgeries at birth and manage complications associated with tethered cord and hydrocephalus.

- Neurologists treat and evaluate nervous system issues, such as seizure disorders.

- Urologists to address kidney, bladder, and bowel dysfunction – many will need to manage their urinary systems with a program of catheterization. Bowel management programs aimed at improving elimination are also designed.

- Ophthalmologists evaluate and treat complications of the eyes.

- Orthotists design and customize various types of assistive technology, including braces, crutches, walkers, and wheelchairs to aid in mobility. As a general rule, the higher the level of the spina bifida defect, the more severe the paralysis, but paralysis does not always occur. Thus, those with low levels may need only short leg braces, whereas those with higher levels do best with a wheelchair, and some may be able to walk unaided.

- Physical therapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and speech/language pathologists aid in rehabilitative therapies and increase independent living skills.

Transition to adulthood

Although many children's hospitals

feature integrated multidisciplinary teams to coordinate healthcare of

youth with spina bifida, the transition to adult healthcare can be

difficult because the above healthcare professionals operate

independently of each other, requiring separate appointments, and

communicate among each other much less frequently. Healthcare

professionals working with adults may also be less knowledgeable about

spina bifida because it is considered a childhood chronic health

condition.

Due to the potential difficulties of the transition, adolescents with

spina bifida and their families are encouraged to begin to prepare for

the transition around ages 14–16, although this may vary depending on

the adolescent's cognitive and physical abilities and available family

support. The transition itself should be gradual and flexible. The

adolescent's multidisciplinary treatment team may aid in the process by

preparing comprehensive, up-to-date documents detailing the adolescent's

medical care, including information about medications, surgery,

therapies, and recommendations. A transition plan and aid in identifying

adult healthcare professionals are also helpful to include in the

transition process.

Further complicating the transition process is the tendency for

youths with spina bifida to be delayed in the development of autonomy, with boys particularly at risk for slower development of independence.

An increased dependence on others (in particular family members) may

interfere with the adolescent's self-management of health-related tasks,

such as catheterization, bowel management, and taking medications.

As part of the transition process, it is beneficial to begin

discussions at an early age about educational and vocational goals,

independent living, and community involvement.

Epidemiology

About 15% of people have spina bifida occulta. Rates of other types of spina bifida vary significantly by country from 0.1 to 5 per 1000 births. On average in developed countries it occurs in about 0.4 per 1000 births. In the United States it affected about 0.7 per 1000 births, and in India about 1.9 per 1000 births. Part of this difference is believed to be due to race, with Caucasians at higher risk, and part due to environmental factors.

In the United States, rates are higher on the East Coast than on

the West Coast, and higher in white people (one case per 1000 live

births) than in black people (0.1–0.4 case per 1000 live births).

Immigrants from Ireland have a higher incidence of spina bifida than do

natives. Highest rates of the defect in the USA can be found in Hispanic youth.

The highest incidence rates worldwide were found in Ireland and

Wales, where three to four cases of myelomeningocele per 1000 population

have been reported during the 1970s, along with more than six cases of anencephaly (both live births and stillbirths)

per 1000 population. The reported overall incidence of myelomeningocele

in the British Isles was 2.0–3.5 cases per 1000 births. Since then, the rate has fallen dramatically with 0.15 per 1000 live births reported in 1998, though this decline is partially accounted for because some fetuses are aborted when tests show signs of spina bifida (see Pregnancy screening above).

Research

- 1980 – Fetal surgical techniques using animal models were first developed at the University of California, San Francisco by Michael R. Harrison, N. Scott Adzick and research colleagues.

- 1994 – A surgical model that simulates the human disease is the fetal lamb model of myelomeningocele (MMC) introduced by Meuli and Adzick in 1994. The MMC-like defect was surgically created at 75 days of gestation (term 145 to 150 days) by a lumbo-sacral laminectomy. Approximately 3 weeks after creation of the defect a reversed latissimus dorsi flap was used to cover the exposed neural placode and the animals were delivered by cesarean section just prior term. Human MMC-like lesions with similar neurological deficit were found in the control newborn lambs. In contrast, animals that underwent closure had near-normal neurological function and well-preserved cytoarchitecture of the covered spinal cord on histopathological examination. Despite mild paraparesis, they were able to stand, walk, perform demanding motor test and demonstrated no signs of incontinence. Furthermore, sensory function of the hind limbs was present clinically and confirmed electrophysiologically. Further studies showed that this model, when combined with a lumbar spinal cord myelotomy leads to the hindbrain herniation characteristic of the Chiari II malformation and that in utero surgery restores normal hindbrain anatomy by stopping the leak of cerebrospinal fluid through the myelomeningocele lesion.

Surgeons at Vanderbilt University, led by Joseph Bruner, attempted to close spina bifida in 4 human fetuses using a skin graft from the mother using a laparoscope. Four cases were performed before stopping the procedure - two of the four fetuses died.

- 1998 – N. Scott Adzick and team at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia performed open fetal surgery for spina bifida in an early gestation fetus (22-week gestation fetus) with a successful outcome. Open fetal surgery for myelomeningocele involves surgically opening the pregnant mother's abdomen and uterus to operate on the fetus. The exposed fetal spinal cord is covered in layers with surrounding fetal tissue at mid-gestation (19–25 weeks) to protect it from further damage caused by prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid. Between 1998 and 2003, Dr. Adzick, and his colleagues in the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment at The Children's Hospital Of Philadelphia, performed prenatal spina bifida repair in 58 mothers and observed significant benefit in the babies.

Fetal surgery after 25 weeks has not shown benefit in subsequent studies.

MOMS trial

Management of myelomeningocele study (MOMS) was a phase III clinical trial designed to compare two approaches to the treatment of spina bifida: surgery before birth and surgery after birth.

The trial concluded that the outcomes after prenatal spina bifida

treatment are improved to the degree that the benefits of the surgery

outweigh the maternal risks. This conclusion requires a value judgment

on the relative value of fetal and maternal outcomes on which opinion is

still divided.

To be specific, the study found that prenatal repair resulted in:

- Reversal of the hindbrain herniation component of the Chiari II malformation

- Reduced need for ventricular shunting (a procedure in which a thin tube is introduced into the brain's ventricles to drain fluid and relieve hydrocephalus)

- Reduced incidence or severity of potentially devastating neurologic effects caused by the spine's exposure to amniotic fluid, such as impaired motor function

At one year of age, 40 percent of the children in the prenatal surgery

group had received a shunt, compared to 83 percent of the children in

the postnatal group. During pregnancy, all the fetuses in the trial had

hindbrain herniation. However, at age 12 months, one-third (36 percent)

of the infants in the prenatal surgery group no longer had any evidence

of hindbrain herniation, compared to only 4 percent in the postnatal

surgery group. Further surveillance is ongoing.

Fetoscopic surgery

In contrast to the open fetal operative approach performed in the

MOMS trial, a minimally invasive fetoscopic approach (akin to 'keyhole'

surgery) has been developed. This approach has been evaluated by

independent authors of a controlled study which showed some benefit in

survivors, but others are more skeptical.

The observations in mothers and their fetuses that were operated

over the past two and a half years by the matured minimally invasive

approach showed the following results: Compared to the open fetal

surgery technique, fetoscopic repair of myelomeningocele results in far

less surgical trauma to the mother, as large incisions of her abdomen

and uterus are not required. In contrast, the initial punctures have a

diameter of 1.2 mm only. As a result, thinning of the uterine wall or dehiscence

which have been among the most worrisome and criticized complications

after the open operative approach do not occur following minimally

invasive fetoscopic closure of spina bifida aperta. The risks of

maternal chorioamnionitis or fetal death as a result of the fetoscopic procedure run below 5%. Women are discharged home from hospital one week after the procedure. There is no need for chronic administration of tocolytic agents

since postoperative uterine contractions are barely ever observed. The

current cost of the entire fetoscopic procedure, including hospital

stay, drugs, perioperative clinical, ECG, ultrasound and

MRI-examinations, is approximately €16,000.

In 2012, these results of the fetoscopic approach were presented

at various national and international meetings, among them at the 1st

European Symposium “Fetal Surgery for Spina bifida“ in April 2012 in Giessen, at the 15th Congress of the German Society for Prenatal Medicine and Obstetrics in May 2012 in Bonn, at the World Congress of the Fetal Medicine Foundation in June 2012 and at the World Congress of the International Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) in Copenhagen in September 2012, and published in abstract form.

Since then more data has emerged. In 2014, two papers were published on fifty one patients.

These papers suggested that the risk to the mother is small. The main

risk appears to be preterm labour, on average at about 33 weeks.