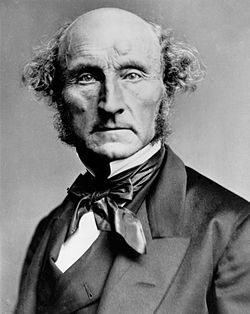

Ludwig von Mises

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises

29 September 1881 |

| Died | 10 October 1973 (aged 92) |

| Institution | University of Vienna (1919–1934) Institut Universitaire des Hautes Études Internationales, Geneva, Switzerland (1934–1940) New York University (1945–1969) |

| Field | Economics, political economy, philosophy of history, epistemology, methodology, rationalism, logic, classical liberalism, libertarianism |

| School or tradition | Austrian School |

| Doctoral advisor | Eugen Böhm von Bawerk |

| Doctoral students | Gottfried Haberler Fritz Machlup Oskar Morgenstern Gerhard Tintner Israel Kirzner |

| Influences | Menger ·Böhm-Bawerk · Wieser · Fetter · Husserl · Say · Kant |

| Contributions | |

| Notes | |

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (German: [ˈluːtvɪç fɔn ˈmiːzəs]; 29 September 1881 – 10 October 1973) was an Austrian School economist, historian, and sociologist. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the societal contributions of classical liberalism. He is best known for his work on praxeology, a study of human choice and action.

Mises emigrated from Austria to the United States in 1940. Since the mid-20th century, libertarian movements have been strongly influenced by Mises's writings. Mises's student Friedrich Hayek viewed Mises as one of the major figures in the revival of classical liberalism in the post-war era. Hayek's work "The Transmission of the Ideals of Freedom" (1951) pays high tribute to the influence of Mises in the 20th century libertarian movement.

Mises's Private Seminar was a leading group of economists. Many of its alumni, including Hayek and Oskar Morgenstern, emigrated from Austria to the United States and Great Britain. Mises has been described as having approximately seventy close students in Austria. The Ludwig von Mises Institute was founded in the United States to continue his teachings.

Biography

Early life

Coat of arms of Ludwig von Mises's great-grandfather, Mayer Rachmiel Mises, awarded upon his 1881 ennoblement by Franz Joseph I of Austria

Ludwig von Mises was born to Jewish parents in the city of Lemberg, Galicia, Austria-Hungary (now Lviv, Ukraine). The family of his father, Arthur Edler von Mises, had been elevated to the Austrian nobility in the 19th century (Edler

indicates a noble landless family) and they had been involved in

financing and constructing railroads. His mother Adele (née Landau) was a

niece of Dr. Joachim Landau, a Liberal Party deputy to the Austrian

Parliament. Arthur von Mises was stationed in Lemberg as a construction engineer with the Czernowitz railway company.

By the age of 12, Mises spoke fluent German, Polish and French, read Latin and could understand Ukrainian. Mises had a younger brother, Richard von Mises, who became a mathematician and a member of the Vienna Circle, and a probability theorist. When Ludwig and Richard were still children, their family moved back to Vienna.

In 1900, Mises attended the University of Vienna, becoming influenced by the works of Carl Menger. Mises's father died in 1903. Three years later, Mises was awarded his doctorate from the school of law in 1906.

Life in Europe

In the years from 1904 to 1914, Mises attended lectures given by Austrian economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. He graduated in February 1906 (Juris Doctor) and started a career as a civil servant in Austria's financial administration.

After a few months, he left to take a trainee position in a

Vienna law firm. During that time, Mises began lecturing on economics

and in early 1909 joined the Vienna Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

During World War I, Mises served as a front officer in the Austro-Hungarian artillery and as an economic adviser to the War Department.

Mises was chief economist for the Austrian Chamber of Commerce and was an economic adviser of Engelbert Dollfuss, the austrofascist but strongly anti-Nazi Austrian Chancellor. Later, Mises was economic adviser to Otto von Habsburg, the Christian democratic politician and claimant to the throne of Austria (which had been legally abolished in 1918 following the Great War). In 1934, Mises left Austria for Geneva, Switzerland, where he was a professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies until 1940.

While in Switzerland, Mises married Margit Herzfeld Serény, a

former actress and widow of Ferdinand Serény. She was the mother of Gitta Sereny.

Work in the United States

In 1940, Mises and his wife fled the German advance in Europe and emigrated to New York City in the United States. He had come to the United States under a grant by the Rockefeller Foundation. Like many other classical liberal scholars who fled to the United States, he received support by the William Volker Fund to obtain a position in American universities. Mises became a visiting professor at New York University and held this position from 1945 until his retirement in 1969, though he was not salaried by the university. Businessman and libertarian commentator Lawrence Fertig, a member of the New York University Board of Trustees, funded Mises and his work.

For part of this period, Mises studied currency issues for the Pan-Europa movement, which was led by Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, a fellow New York University faculty member and Austrian exile. In 1947, Mises became one of the founding members of the Mont Pelerin Society.

In 1962, Mises received the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art for political economy at the Austrian Embassy in Washington, D.C.

Mises retired from teaching at the age of 87 and died at the age of 92 in New York. He is buried at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. Grove City College houses the 20,000-page archive of Mises papers and unpublished works. The personal library of Mises was given to Hillsdale College as bequeathed in his will.

At one time, Mises praised the work of writer Ayn Rand

and she generally looked on his work with favor, but the two had a

volatile relationship, with strong disagreements for example over the

moral basis of capitalism.

Contributions and influence in economics

Mises wrote and lectured extensively on behalf of classical liberalism. In his magnum opus Human Action, Mises adopted praxeology as a general conceptual foundation of the social sciences and set forth his methodological approach to economics.

Mises was for economic non-interventionism and was an anti-imperialist. He referred to the Great War

as such a watershed event in human history and wrote that "war has

become more fearful and destructive than ever before because it is now

waged with all the means of the highly developed technique that the free

economy has created. Bourgeois civilization has built railroads and

electric power plants, has invented explosives and airplanes, in order

to create wealth. Imperialism has placed the tools of peace in the

service of destruction. With modern means it would be easy to wipe out

humanity at one blow."

In 1920, Mises introduced in an article his Economic Calculation Problem as a critique of socialisms which are based on planned economies and renunciations of the price mechanism. In his first article "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth", Mises describes the nature of the price system under capitalism and describes how individual subjective values are translated into the objective information necessary for rational allocation of resources in society.

Mises argued that the pricing systems in socialist economies were

necessarily deficient because if a public entity owned all the means of production, no rational prices could be obtained for capital goods

as they were merely internal transfers of goods and not "objects of

exchange", unlike final goods. Therefore, they were unpriced and hence

the system would be necessarily irrational, as the central planners

would not know how to allocate the available resources efficiently. He wrote that "rational economic activity is impossible in a socialist commonwealth". Mises developed his critique of socialism more completely in his 1922 book Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, arguing that the market price system is an expression of praxeology and can not be replicated by any form of bureaucracy.

Friends and students of Mises in Europe included Wilhelm Röpke and Alfred Müller-Armack (advisors to German chancellor Ludwig Erhard), Jacques Rueff (monetary advisor to Charles de Gaulle), Gottfried Haberler (later a professor at Harvard), Lionel, Lord Robbins (of the London School of Economics), Italian President Luigi Einaudi and Leonid Hurwicz, recipient of the 2007 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Economist and political theorist Friedrich Hayek

first came to know Mises while working as his subordinate at a

government office dealing with Austria's post-World War I debt. While

toasting Mises at a party in 1956, Hayek said: "I came to know him as

one of the best educated and informed men I have ever known".

Mises's seminars in Vienna fostered lively discussion among established

economists there. The meetings were also visited by other important

economists who happened to be traveling through Vienna.

At his New York University seminar and at informal meetings at

his apartment, Mises attracted college and high school students who had

heard of his European reputation. They listened while he gave carefully

prepared lectures from notes. Among those who attended his informal seminar over the course of two decades in New York were Israel Kirzner, Hans Sennholz, Ralph Raico, Leonard Liggio, George Reisman and Murray Rothbard. Mises's work also influenced other Americans, including Benjamin Anderson, Leonard Read, Henry Hazlitt, Max Eastman, legal scholar Sylvester J. Petro and novelist Ayn Rand.

Reception

Debates about Mises's arguments

Economic historian Bruce Caldwell wrote that in the mid-20th century, with the ascendance of positivism and Keynesianism, Mises came to be regarded by many as the "archetypal 'unscientific' economist". In a 1957 review of his book The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality, The Economist said of Mises: "Professor von Mises has a splendid analytical mind and an admirable passion for liberty; but as a student of human nature he is worse than null and as a debater he is of Hyde Park standard". Conservative commentator Whittaker Chambers published a similarly negative review of that book in the National Review, stating that Mises's thesis that anti-capitalist sentiment was rooted in "envy" epitomized "know-nothing conservatism" at its "know-nothingest".

Scholar Scott Scheall called economist Terence Hutchison "the most persistent critic of Mises's apriorism", starting in Hutchison's 1938 book The Significance and Basic Postulates of Economic Theory and in later publications such as his 1981 book The Politics and Philosophy of Economics: Marxians, Keynesians, and Austrians. Scheall noted that Friedrich Hayek, later in his life (after Mises died), also expressed reservations about Mises's apriorism,

such as in a 1978 interview where Hayek said that he "never could

accept the ... almost eighteenth-century rationalism in his [Mises's]

argument".

In a 1978 interview, Hayek said about Mises's book Socialism:

At first we all felt he was frightfully exaggerating and even offensive in tone. You see, he hurt all our deepest feelings, but gradually he won us around, although for a long time I had to – I just learned he was usually right in his conclusions, but I was not completely satisfied with his argument.

Economist Milton Friedman considered Mises inflexible in his thinking:

The story I remember best happened at the initial Mont Pelerin meeting when he got up and said, "You're all a bunch of socialists." We were discussing the distribution of income, and whether you should have progressive income taxes. Some of the people there were expressing the view that there could be a justification for it. Another occasion which is equally telling: Fritz Machlup was a student of Mises's, one of his most faithful disciples. At one of the Mont Pelerin meetings, Machlup gave a talk in which I think he questioned the idea of a gold standard; he came out in favor of floating exchange rates. Mises was so mad he wouldn't speak to Machlup for three years. Some people had to come around and bring them together again. It's hard to understand; you can get some understanding of it by taking into account how people like Mises were persecuted in their lives.

Economist Murray Rothbard,

who studied under Mises, agreed he was uncompromising, but disputes

reports of his abrasiveness. In his words, Mises was "unbelievably

sweet, constantly finding research projects for students to do,

unfailingly courteous, and never bitter" about the discrimination he

received at the hands of the economic establishment of his time.

After Mises died, his widow Margit quoted a passage that he had written about Benjamin Anderson. She said it best described Mises's own personality:

His most eminent qualities were his inflexible honesty, his unhesitating sincerity. He never yielded. He always freely enunciated what he considered to be true. If he had been prepared to suppress or only to soften his criticisms of popular, but irresponsible, policies, the most influential positions and offices would have been offered him. But he never compromised.

Debates about fascism

Marxists Herbert Marcuse and Perry Anderson

as well as German writer Claus-Dieter Krohn criticized Mises for

writing approvingly of Italian fascism, especially for its suppression

of leftist elements in Mises's 1927 book Liberalism. In 2009, economist J. Bradford DeLong and sociologist Richard Seymour repeated the criticism.

Mises wrote in the 1927 book:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history. But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error.

Mises biographer Jörg Guido Hülsmann

says that critics who suggest that Mises supported fascism are "absurd"

as he notes that the full quote describes fascism as dangerous. He

notes that Mises thought it was a "fatal error" to think that it was

more than an "emergency makeshift" against the looming threat of

communism and socialism as exemplified by the Bolsheviks in Russia.

Bibliography

Books

- The Theory of Money and Credit (1912, enlarged US edition 1953)

- Nation, State, and Economy (1919)

- "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth" (1920) (article)

- Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis (1922, 1932, 1951)

- Liberalismus (1927, 1962)

- Translated into English with the new title, The Free and Prosperous Commonwealth

- A Critique of Interventionism (1929) Full text available online.

- Epistemological Problems of Economics (1933, 1960)

- Memoirs (1940)

- Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (1941, 1998)

- Omnipotent Government: The Rise of Total State and Total War (1944)

- Bureaucracy (1944, 1962)

- Planned Chaos (1947, added to 1951 edition of Socialism)

- Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (1949, 1963, 1966, 1996)

- Planning for Freedom (1952, enlarged editions in 1962, 1974, and 1980)

- The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality (1956)

- Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Evolution (1957)

- The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science (1962)

- The Historical Setting of the Austrian School of Economics (1969)

- Notes and Recollections (1978)

- The Clash of Group Interests and Other Essays (1978)

- On the Manipulation of Money and Credit (1978)

- The Causes of the Economic Crisis, reissue

- Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow (1979, lectures given in 1959)

- Money, Method, and the Market Process (1990)

- Economic Freedom and Interventionism (1990)

- The Free Market and Its Enemies (2004, lectures given in 1951)

- Marxism Unmasked: From Delusion to Destruction (2006, lectures given in 1952)

- Ludwig von Mises on Money and Inflation (2010, lectures given in the 1960s)

Book reviews