| |

| Original author(s) | Vijay Pande |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Pande Laboratory, Sony, Nvidia, ATI Technologies, Joseph Coffland, Cauldron Development |

| Initial release | October 1, 2000 |

| Stable release |

7.6.13

/ May 5, 2020

|

| Operating system | Microsoft Windows, macOS, Linux |

| Platform | Cross-platform software: IA-32, x86-64; ARM architecture |

| Available in | English |

| Type | Distributed computing |

| License | Proprietary software |

| Website | foldingathome |

Folding@home (FAH or F@h) is a distributed computing project aimed to help scientists develop new therapeutics to a variety of diseases by the means of simulating protein dynamics. This includes the process of protein folding and the movements of proteins, and is reliant on the simulations run on the volunteers' personal computers. Folding@home is currently based at Washington University in St. Louis and led by Greg Bowman, a former student of Pande.

The project utilizes central processing units (CPUs), graphics processing units (GPUs), PlayStation 3s, Message Passing Interface (used for computing on multi-core processors), and some Sony Xperia smartphones for distributed computing and scientific research. The project uses statistical simulation methodology that is a paradigm shift from traditional computing methods. As part of the client–server model network architecture, the volunteered machines each receive pieces of a simulation (work units), complete them, and return them to the project's database servers, where the units are compiled into an overall simulation. Volunteers can track their contributions on the Folding@home website, which makes volunteers' participation competitive and encourages long-term involvement.

Folding@home is one of the world's fastest computing systems. With heightened interest in the project as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the system achieved a speed of approximately 1.22 exaflops by late March 2020 and reaching 2.43 exaflops by April 12, 2020, making it the world's first exaflop computing system. This level of performance from its large-scale computing network has allowed researchers to run computationally costly atomic-level simulations of protein folding thousands of times longer than formerly achieved. Since its launch on October 1, 2000, the Pande Lab has produced 223 scientific research papers as a direct result of Folding@home. Results from the project's simulations agree well with experiments.

Background

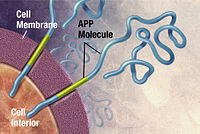

A protein before and after folding. It starts in an unstable random coil state and finishes in its native state conformation.

Proteins are an essential component to many biological functions and participate in virtually all processes within biological cells. They often act as enzymes, performing biochemical reactions including cell signaling, molecular transportation, and cellular regulation. As structural elements, some proteins act as a type of skeleton for cells, and as antibodies, while other proteins participate in the immune system. Before a protein can take on these roles, it must fold into a functional three-dimensional structure, a process that often occurs spontaneously and is dependent on interactions within its amino acid

sequence and interactions of the amino acids with their surroundings.

Protein folding is driven by the search to find the most energetically

favorable conformation of the protein, i.e., its native state.

Thus, understanding protein folding is critical to understanding what a

protein does and how it works, and is considered a holy grail of computational biology. Despite folding occurring within a crowded cellular environment, it typically proceeds smoothly. However, due to a protein's chemical properties or other factors, proteins may misfold,

that is, fold down the wrong pathway and end up misshapen. Unless

cellular mechanisms can destroy or refold misfolded proteins, they can

subsequently aggregate and cause a variety of debilitating diseases.

Laboratory experiments studying these processes can be limited in scope

and atomic detail, leading scientists to use physics-based computing

models that, when complementing experiments, seek to provide a more

complete picture of protein folding, misfolding, and aggregation.

Due to the complexity of proteins' conformation or configuration space

(the set of possible shapes a protein can take), and limits in

computing power, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations have been

severely limited in the timescales which they can study. While most

proteins typically fold in the order of milliseconds, before 2010, simulations could only reach nanosecond to microsecond timescales. General-purpose supercomputers

have been used to simulate protein folding, but such systems are

intrinsically costly and typically shared among many research groups.

Further, because the computations in kinetic models occur serially,

strong scaling of traditional molecular simulations to these architectures is exceptionally difficult. Moreover, as protein folding is a stochastic process

(i.e., random) and can statistically vary over time, it is challenging

computationally to use long simulations for comprehensive views of the

folding process.

Folding@home uses Markov state models,

like the one diagrammed here, to model the possible shapes and folding

pathways a protein can take as it condenses from its initial randomly

coiled state (left) into its native 3-D structure (right).

Protein folding does not occur in one step. Instead, proteins spend most of their folding time, nearly 96% in some cases, waiting in various intermediate conformational states, each a local thermodynamic free energy minimum in the protein's energy landscape. Through a process known as adaptive sampling, these conformations are used by Folding@home as starting points for a set of simulation trajectories. As the simulations discover more conformations, the trajectories are restarted from them, and a Markov state model (MSM) is gradually created from this cyclic process. MSMs are discrete-time master equation

models which describe a biomolecule's conformational and energy

landscape as a set of distinct structures and the short transitions

between them. The adaptive sampling Markov state model method

significantly increases the efficiency of simulation as it avoids

computation inside the local energy minimum itself, and is amenable to

distributed computing (including on GPUGRID) as it allows for the statistical aggregation of short, independent simulation trajectories.

The amount of time it takes to construct a Markov state model is

inversely proportional to the number of parallel simulations run, i.e.,

the number of processors available. In other words, it achieves linear parallelization, leading to an approximately four orders of magnitude

reduction in overall serial calculation time. A completed MSM may

contain tens of thousands of sample states from the protein's phase space

(all the conformations a protein can take on) and the transitions

between them. The model illustrates folding events and pathways (i.e.,

routes) and researchers can later use kinetic clustering to view a

coarse-grained representation of the otherwise highly detailed model.

They can use these MSMs to reveal how proteins misfold and to

quantitatively compare simulations with experiments.

Between 2000 and 2010, the length of the proteins Folding@home

has studied have increased by a factor of four, while its timescales for

protein folding simulations have increased by six orders of magnitude. In 2002, Folding@home used Markov state models to complete approximately a million CPU days of simulations over the span of several months, and in 2011, MSMs parallelized another simulation that required an aggregate 10 million CPU hours of computing. In January 2010, Folding@home used MSMs to simulate the dynamics of the slow-folding 32-residue

NTL9 protein out to 1.52 milliseconds, a timescale consistent with

experimental folding rate predictions but a thousand times longer than

formerly achieved. The model consisted of many individual trajectories,

each two orders of magnitude shorter, and provided an unprecedented

level of detail into the protein's energy landscape. In 2010, Folding@home researcher Gregory Bowman was awarded the Thomas Kuhn Paradigm Shift Award from the American Chemical Society for the development of the open-source MSMBuilder software and for attaining quantitative agreement between theory and experiment.

For his work, Pande was awarded the 2012 Michael and Kate Bárány Award

for Young Investigators for "developing field-defining and

field-changing computational methods to produce leading theoretical

models for protein and RNA folding",

and the 2006 Irving Sigal Young Investigator Award for his simulation

results which "have stimulated a re-examination of the meaning of both

ensemble and single-molecule measurements, making Pande's efforts

pioneering contributions to simulation methodology."

Examples of application in biomedical research

Protein misfolding can result in a variety of diseases including Alzheimer's disease, cancer, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease, sickle-cell anemia, and type II diabetes. Cellular infection by viruses such as HIV and influenza also involve folding events on cell membranes.

Once protein misfolding is better understood, therapies can be

developed that augment cells' natural ability to regulate protein

folding. Such therapies

include the use of engineered molecules to alter the production of a

given protein, help destroy a misfolded protein, or assist in the

folding process.

The combination of computational molecular modeling and experimental

analysis has the possibility to fundamentally shape the future of

molecular medicine and the rational design of therapeutics, such as expediting and lowering the costs of drug discovery.

The goal of the first five years of Folding@home was to make advances

in understanding folding, while the current goal is to understand

misfolding and related disease, especially Alzheimer's.

The simulations run on Folding@home are used in conjunction with laboratory experiments, but researchers can use them to study how folding in vitro

differs from folding in native cellular environments. This is

advantageous in studying aspects of folding, misfolding, and their

relationships to disease that are difficult to observe experimentally.

For example, in 2011, Folding@home simulated protein folding inside a ribosomal exit tunnel, to help scientists better understand how natural confinement and crowding might influence the folding process. Furthermore, scientists typically employ chemical denaturants

to unfold proteins from their stable native state. It is not generally

known how the denaturant affects the protein's refolding, and it is

difficult to experimentally determine if these denatured states contain

residual structures which may influence folding behavior. In 2010,

Folding@home used GPUs to simulate the unfolded states of Protein L, and predicted its collapse rate in strong agreement with experimental results.

The large data sets from the project are freely available for

other researchers to use upon request and some can be accessed from the

Folding@home website. The Pande lab has collaborated with other molecular dynamics systems such as the Blue Gene supercomputer,

and they share Folding@home's key software with other researchers, so

that the algorithms which benefited Folding@home may aid other

scientific areas.

In 2011, they released the open-source Copernicus software, which is

based on Folding@home's MSM and other parallelizing methods and aims to

improve the efficiency and scaling of molecular simulations on large computer clusters or supercomputers. Summaries of all scientific findings from Folding@home are posted on the Folding@home website after publication.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is an incurable neurodegenerative disease which most often affects the elderly and accounts for more than half of all cases of dementia. Its exact cause remains unknown, but the disease is identified as a protein misfolding disease. Alzheimer's is associated with toxic aggregations of the amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide, caused by Aβ misfolding and clumping together with other Aβ peptides. These Aβ aggregates then grow into significantly larger senile plaques, a pathological marker of Alzheimer's disease. Due to the heterogeneous nature of these aggregates, experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance

(NMR) have had difficulty characterizing their structures. Moreover,

atomic simulations of Aβ aggregation are highly demanding

computationally due to their size and complexity.

Preventing Aβ aggregation is a promising method to developing

therapeutic drugs for Alzheimer's disease, according to Naeem and Fazili

in a literature review article.

In 2008, Folding@home simulated the dynamics of Aβ aggregation in

atomic detail over timescales of the order of tens of seconds. Prior

studies were only able to simulate about 10 microseconds. Folding@home

was able to simulate Aβ folding for six orders of magnitude longer than

formerly possible. Researchers used the results of this study to

identify a beta hairpin that was a major source of molecular interactions within the structure.

The study helped prepare the Pande lab for future aggregation studies

and for further research to find a small peptide which may stabilize the

aggregation process.

In December 2008, Folding@home found several small drug candidates which appear to inhibit the toxicity of Aβ aggregates. In 2010, in close cooperation with the Center for Protein Folding Machinery, these drug leads began to be tested on biological tissue. In 2011, Folding@home completed simulations of several mutations

of Aβ that appear to stabilize the aggregate formation, which could aid

in the development of therapeutic drug therapies for the disease and

greatly assist with experimental nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of Aβ oligomers.

Later that year, Folding@home began simulations of various Aβ fragments

to determine how various natural enzymes affect the structure and

folding of Aβ.

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease is a neurodegenerative genetic disorder that is associated with protein misfolding and aggregation. Excessive repeats of the glutamine amino acid at the N-terminus of the huntingtin protein

cause aggregation, and although the behavior of the repeats is not

completely understood, it does lead to the cognitive decline associated

with the disease. As with other aggregates, there is difficulty in experimentally determining its structure.

Scientists are using Folding@home to study the structure of the

huntingtin protein aggregate and to predict how it forms, assisting with

rational drug design methods to stop the aggregate formation.

The N17 fragment of the huntingtin protein accelerates this

aggregation, and while there have been several mechanisms proposed, its

exact role in this process remains largely unknown. Folding@home has simulated this and other fragments to clarify their roles in the disease. Since 2008, its drug design methods for Alzheimer's disease have been applied to Huntington's.

Cancer

More than half of all known cancers involve mutations of p53, a tumor suppressor protein present in every cell which regulates the cell cycle and signals for cell death in the event of damage to DNA.

Specific mutations in p53 can disrupt these functions, allowing an

abnormal cell to continue growing unchecked, resulting in the

development of tumors. Analysis of these mutations helps explain the root causes of p53-related cancers. In 2004, Folding@home was used to perform the first molecular dynamics study of the refolding of p53's protein dimer in an all-atom simulation of water.

The simulation's results agreed with experimental observations and gave

insights into the refolding of the dimer that were formerly

unobtainable. This was the first peer reviewed publication on cancer from a distributed computing project.

The following year, Folding@home powered a new method to identify the

amino acids crucial for the stability of a given protein, which was then

used to study mutations of p53. The method was reasonably successful in

identifying cancer-promoting mutations and determined the effects of

specific mutations which could not otherwise be measured experimentally.

Folding@home is also used to study protein chaperones, heat shock proteins which play essential roles in cell survival by assisting with the folding of other proteins in the crowded

and chemically stressful environment within a cell. Rapidly growing

cancer cells rely on specific chaperones, and some chaperones play key

roles in chemotherapy

resistance. Inhibitions to these specific chaperones are seen as

potential modes of action for efficient chemotherapy drugs or for

reducing the spread of cancer.

Using Folding@home and working closely with the Center for Protein

Folding Machinery, the Pande lab hopes to find a drug which inhibits

those chaperones involved in cancerous cells. Researchers are also using Folding@home to study other molecules related to cancer, such as the enzyme Src kinase, and some forms of the engrailed homeodomain: a large protein which may be involved in many diseases, including cancer. In 2011, Folding@home began simulations of the dynamics of the small knottin protein EETI, which can identify carcinomas in imaging scans by binding to surface receptors of cancer cells.

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) is a protein that helps T cells of the immune system attack pathogens and tumors. However, its use as a cancer treatment is restricted due to serious side effects such as pulmonary edema.

IL-2 binds to these pulmonary cells differently than it does to T

cells, so IL-2 research involves understanding the differences between

these binding mechanisms. In 2012, Folding@home assisted with the

discovery of a mutant form of IL-2 which is three hundred times more

effective in its immune system role but carries fewer side effects. In

experiments, this altered form significantly outperformed natural IL-2

in impeding tumor growth. Pharmaceutical companies have expressed interest in the mutant molecule, and the National Institutes of Health are testing it against a large variety of tumor models to try to accelerate its development as a therapeutic.

Osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta,

known as brittle bone disease, is an incurable genetic bone disorder

which can be lethal. Those with the disease are unable to make

functional connective bone tissue. This is most commonly due to a

mutation in Type-I collagen, which fulfills a variety of structural roles and is the most abundant protein in mammals. The mutation causes a deformation in collagen's triple helix structure, which if not naturally destroyed, leads to abnormal and weakened bone tissue. In 2005, Folding@home tested a new quantum mechanical method that improved upon prior simulation methods, and which may be useful for future computing studies of collagen.

Although researchers have used Folding@home to study collagen folding

and misfolding, the interest stands as a pilot project compared to Alzheimer's and Huntington's research.

Viruses

Folding@home is assisting in research towards preventing some viruses, such as influenza and HIV, from recognizing and entering biological cells. In 2011, Folding@home began simulations of the dynamics of the enzyme RNase H, a key component of HIV, to try to design drugs to deactivate it. Folding@home has also been used to study membrane fusion, an essential event for viral infection and a wide range of biological functions. This fusion involves conformational changes of viral fusion proteins and protein docking, but the exact molecular mechanisms behind fusion remain largely unknown.

Fusion events may consist of over a half million atoms interacting for

hundreds of microseconds. This complexity limits typical computer

simulations to about ten thousand atoms over tens of nanoseconds: a

difference of several orders of magnitude.

The development of models to predict the mechanisms of membrane fusion

will assist in the scientific understanding of how to target the process

with antiviral drugs.

In 2006, scientists applied Markov state models and the Folding@home

network to discover two pathways for fusion and gain other mechanistic

insights.

Following detailed simulations from Folding@home of small cells known as vesicles, in 2007, the Pande lab introduced a new computing method to measure the topology of its structural changes during fusion. In 2009, researchers used Folding@home to study mutations of influenza hemagglutinin, a protein that attaches a virus to its host cell and assists with viral entry. Mutations to hemagglutinin affect how well the protein binds to a host's cell surface receptor molecules, which determines how infective the virus strain is to the host organism. Knowledge of the effects of hemagglutinin mutations assists in the development of antiviral drugs.

As of 2012, Folding@home continues to simulate the folding and

interactions of hemagglutinin, complementing experimental studies at the

University of Virginia.

In March 2020, Folding@home launched a program to assist

researchers around the world who are working on finding a cure and

learning more about the coronavirus pandemic.

The initial wave of projects simulate potentially druggable protein

targets from SARS-CoV-2 virus, and the related SARS-CoV virus, about

which there is significantly more data available.

Drug design

Drugs function by binding to specific locations on target molecules and causing some desired change, such as disabling a target or causing a conformational change.

Ideally, a drug should act very specifically, and bind only to its

target without interfering with other biological functions. However, it

is difficult to precisely determine where and how tightly two molecules will bind. Due to limits in computing power, current in silico methods usually must trade speed for accuracy; e.g., use rapid protein docking methods instead of computationally costly free energy calculations. Folding@home's computing performance allows researchers to use both methods, and evaluate their efficiency and reliability. Computer-assisted drug design has the potential to expedite and lower the costs of drug discovery. In 2010, Folding@home used MSMs and free energy calculations to predict the native state of the villin protein to within 1.8 angstrom (Å) root mean square deviation (RMSD) from the crystalline structure experimentally determined through X-ray crystallography. This accuracy has implications to future protein structure prediction methods, including for intrinsically unstructured proteins. Scientists have used Folding@home to research drug resistance by studying vancomycin, an antibiotic drug of last resort, and beta-lactamase, a protein that can break down antibiotics like penicillin.

Chemical activity occurs along a protein's active site.

Traditional drug design methods involve tightly binding to this site

and blocking its activity, under the assumption that the target protein

exists in one rigid structure. However, this approach works for

approximately only 15% of all proteins. Proteins contain allosteric sites

which, when bound to by small molecules, can alter a protein's

conformation and ultimately affect the protein's activity. These sites

are attractive drug targets, but locating them is very computationally costly. In 2012, Folding@home and MSMs were used to identify allosteric sites in three medically relevant proteins: beta-lactamase, interleukin-2, and RNase H.

Approximately half of all known antibiotics interfere with the workings of a bacteria's ribosome, a large and complex biochemical machine that performs protein biosynthesis by translating messenger RNA into proteins. Macrolide antibiotics clog the ribosome's exit tunnel, preventing synthesis of essential bacterial proteins. In 2007, the Pande lab received a grant to study and design new antibiotics. In 2008, they used Folding@home to study the interior of this tunnel and how specific molecules may affect it. The full structure of the ribosome was determined only as of 2011, and Folding@home has also simulated ribosomal proteins, as many of their functions remain largely unknown.

Potential applications in biomedical research

There are many more protein misfolding promoted diseases

that can be benefited from Folding@home to either discern the misfolded

protein structure or the misfolding kinetics, and assist in drug design

in the future. The often fatal prion diseases is among the most significant.

Prion diseases

A prion (PrP) is a transmembrane cellular protein found widely in eukaryotic cells. In mammals, it is more abundant in the central nervous system.

Although its function is unknown, its high conservation among species

indicates an important role in the cellular function. The

conformational change from the normal prion protein (PrPc, stands for

cellular) to the disease causing isoform PrPSc (stands for prototypical prion disease–scrapie) causes a host of diseases collectly known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), including Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in bovine, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and fatal insomnia in human, chronic wasting disease (CWD) in the deer family. The conformational change is widely accepted as the result of protein misfolding.

What distinguishes TSEs from other protein misfolding diseases is its

transmissible nature. The ‘seeding’ of the infectious PrPSc, either

arising spontaneously, hereditary or acquired via exposure to

contaminated tissues, can cause a chain reaction of transforming normal PrPc into fibrils aggregates or amyloid like plaques consist of PrPSc.

The molecular structure of PrPSc has not been fully characterized

due to its aggregated nature. Neither is known much about the

mechanism of the protein misfolding nor its kinetics.

Using the known structure of PrPc and the results of the in vitro and

in vivo studies described below, Folding@home could be valuable in

elucidating how PrPSc is formed and how the infectious protein arrange

themselves to form fibrils and amyloid like plaques, bypassing the

requirement to purify PrPSc or dissolve the aggregates.

The PrPc has been enzymatically dissociated from the membrane and purified, its structure studied using structure characterization techniques such as NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. Post-translational PrPc has 231 amino acids (aa) in murine. The molecule consists of a long and unstructured amino terminal region spanning up to aa residue 121 and a structured carboxy terminal domain. This globular domain harbours two short sheet-forming anti-parallel β-strands (aa 128 to 130 and aa 160 to 162 in murine PrPc) and three α-helices (helix I: aa 143 to 153; helix II: aa 171 to 192; helix III: aa 199 to 226 in murine PrPc), Helices II and III are anti-parallel orientated and connected by a short loop. Their structural stability is supported by a disulfide bridge,

which is parallel to both sheet-forming β-strands. These α-helices and

the β-sheet form the rigid core of the globular domain of PrPc.

The disease causing PrPSc is proteinase K

resistant and insoluble. Attempts to purify it from the brains of

infected animals invariably yield heterogeneous mixtures and aggregated

states that are not amenable to characterization by NMR spectroscopy or

X-ray crystallography. However, it is a general consensus that PrPSc

contains a high percentage of tightly stacked β-sheets than the normal

PrPc that renders the protein insoluble and resistant to proteinase.

Using techniques of cryoelectron microscopy

and structural modeling based on similar common protein structures, it

has been discovered that PrPSc contains ß-sheets in the region of aa

81-95 to aa 171, while the carboxy terminal structure is supposedly

preserved, retaining the disulfide-linked α-helical conformation in the

normal PrPc. These ß-sheets form a parallel left-handed beta-helix.

Three PrPSc molecules are believed to form a primary unit and therefore

build the basis for the so-called scrapie-associated fibrils.

The catalytic activity depends on the size of the particle. PrPSc

particles which consist of only 14-28 PrPc molecules exhibit the highest

rate of infectivity and conversion.

Despite the difficulty to purify and characterize PrPSc, from the known molecular structure of PrPc and using transgenic mice and N-terminal deletion,

the potential ‘hot spots’ of protein misfolding leading to the

pathogenic PrPSc could be deduced and Folding@home could be of great

value in confirming these. Studies found that both the primary and secondary structure of the prion protein can be of significance of the conversion.

There are more than twenty mutations of the prion protein gene (PRNP)

that are known to be associated with or that are directly linked to the

hereditary form of human TSEs [56], indicating single amino acids at

certain position, likely within the carboxy domain, of the PrPc can affect the susceptibility to TSEs.

The post-translational amino terminal region of PrPc consists of

residues 23-120 which make up nearly half of the amino sequence of

full-length matured PrPc. There are two sections in the amino terminal

region that may influence conversion. First, residues 52-90 contains an

octapeptide repeat (5 times) region that likely influences the initial

binding (via the octapeptide repeats) and also the actual conversion via

the second section of aa 108–124. The highly hydrophobic AGAAAAGA is located between aa residue 113 and 120 and is described as putative aggregation site, although this sequence requires its flanking parts to form fibrillar aggregates.

In the carboxy globular domain, among the three helices, study show that helix II has a significant higher propensity to β-strand conformation.

Due to the high conformational flexvoribility seen between residues

114-125 (part of the unstructured N-terminus chain) and the high

β-strand propensity of helix II, only moderate changes in the

environmental conditions or interactions might be sufficient to induce

misfolding of PrPc and subsequent fibril formation.

Other studies of NMR structures of PrPc showed that these

residues (~108–189) contain most of the folded domain including both

β-strands, the first two α-helices, and the loop/turn regions connecting

them, but not the helix III. Small changes within the loop/turn structures of PrPc itself could be important in the conversion as well.

In another study, Riek et al. showed that the two small regions of

β-strand upstream of the loop regions act as a nucleation site for the

conformational conversion of the loop/turn and α-helical structures in

PrPc to β-sheet.

The energy threshold for the conversion are not necessarily high. The folding stability, i.e. the free energy of a globular protein in its environment is in the range of one or two hydrogen bonds thus allows the transition to an isoform without the requirement of high transition energy.

From the respective of the interactions among the PrPc molecules,

hydrophobic interactions play a crucial role in the formation of

β-sheets, a hallmark of PrPSc, as the sheets bring fragments of polypeptide chains into close proximity. Indeed, Kutznetsov and Rackovsky showed that disease-promoting mutations in the human PrPc had a

statistically significant tendency towards increasing local

hydrophobicity.

In vitro experiments showed the kinetics of misfolding has an

initial lag phase followed by a rapid growth phase of fibril formation.

It is likely that PrPc goes through some intermediate states, such as

at least partially unfolded or degraded, before finally ending up as

part of an amyloid fibril.

Patterns of participation

Like other distributed computing projects, Folding@home is an online citizen science

project. In these projects non-specialists contribute computer

processing power or help to analyse data produced by professional

scientists. Participants receive little or no obvious reward.

Research has been carried out into the motivations of citizen

scientists and most of these studies have found that participants are

motivated to take part because of altruistic reasons; that is, they want

to help scientists and make a contribution to the advancement of their

research.

Many participants in citizen science have an underlying interest in the

topic of the research and gravitate towards projects that are in

disciplines of interest to them. Folding@home is no different in that

respect.

Research carried out recently on over 400 active participants revealed

that they wanted to help make a contribution to research and that many

had friends or relatives affected by the diseases that the Folding@home

scientists investigate.

Folding@home attracts participants who are computer hardware

enthusiasts (sometimes called ‘overclockers’). These groups bring

considerable expertise to the project and are able to build computers

with advanced processing power.

Other distributed computing projects attract these types of

participants and projects are often used to benchmark the performance of

modified computers, and this aspect of the hobby is accommodated

through the competitive nature of the project. Individuals and teams can

compete to see who can process the most computer processing units

(CPUs).

This latest research on Folding@home involving interview and

ethnographic observation of online groups showed that teams of hardware

enthusiasts can sometimes work together, sharing best practice with

regard to maximising processing output. Such teams can become communities of practice,

with a shared language and online culture. This pattern of

participation has been observed in other distributed computing projects.

Another key observation of Folding@home participants is that many are male.

This has also been observed in other distributed projects. Furthermore,

many participants work in computer and technology-based jobs and

careers.

Not all Folding@home participants are hardware enthusiasts. Many

participants run the project software on unmodified machines and do take

part competitively. Over 100,000 participants are involved in

Folding@home. However, it is difficult to ascertain what proportion of

participants are hardware enthusiasts. Although, according to the

project managers, the contribution of the enthusiast community is

substantially larger in terms of processing power.

Performance

Computing

power of Folding@home and the fastest supercomputer from April 2004 to

October 2012. Between June 2007 and June 2011, Folding@home (red)

exceeded the performance of Top500's fastest supercomputer (black). However it was eclipsed by K computer in November 2011 and Blue Gene/Q in June 2012.

Supercomputer FLOPS performance is assessed by running the legacy LINPACK

benchmark. This short-term testing has difficulty in accurately

reflecting sustained performance on real-world tasks because LINPACK

more efficiently maps to supercomputer hardware. Computing systems vary

in architecture and design, so direct comparison is difficult. Despite

this, FLOPS remain the primary speed metric used in supercomputing. In contrast, Folding@home determines its FLOPS using wall-clock time by measuring how much time its work units take to complete.

On September 16, 2007, due in large part to the participation of

PlayStation 3 consoles, the Folding@home project officially attained a

sustained performance level higher than one native petaFLOPS, becoming the first computing system of any kind to do so. Top500's fastest supercomputer at the time was BlueGene/L, at 0.280 petaFLOPS. The following year, on May 7, 2008, the project attained a sustained performance level higher than two native petaFLOPS, followed by the three and four native petaFLOPS milestones on August 2008 and September 28, 2008 respectively. On February 18, 2009, Folding@home achieved five native petaFLOPS, and was the first computing project to meet these five levels. In comparison, November 2008's fastest supercomputer was IBM's Roadrunner at 1.105 petaFLOPS.

On November 10, 2011, Folding@home's performance exceeded six native

petaFLOPS with the equivalent of nearly eight x86 petaFLOPS.

In mid-May 2013, Folding@home attained over seven native petaFLOPS,

with the equivalent of 14.87 x86 petaFLOPS. It then reached eight native

petaFLOPS on June 21, followed by nine on September 9 of that year,

with 17.9 x86 petaFLOPS. On May 11, 2016 Folding@home announced that it was moving towards reaching the 100 x86 petaFLOPS mark.

Further use grew from increased awareness and participation in

the project from the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. On March 20, 2020

Folding@home announced via Twitter that it was running with over 470

native petaFLOPS, the equivalent of 958 x86 petaFLOPS. By March 25 it reached 768 petaFLOPS, or 1.5 x86 exaFLOPS, making it the first exaFLOP computing system.

Points

Similarly

to other distributed computing projects, Folding@home quantitatively

assesses user computing contributions to the project through a credit

system.

All units from a given protein project have uniform base credit, which

is determined by benchmarking one or more work units from that project

on an official reference machine before the project is released.

Each user receives these base points for completing every work unit,

though through the use of a passkey they can receive added bonus points

for reliably and rapidly completing units which are more demanding

computationally or have a greater scientific priority. Users may also receive credit for their work by clients on multiple machines. This point system attempts to align awarded credit with the value of the scientific results.

Users can register their contributions under a team, which

combine the points of all their members. A user can start their own

team, or they can join an existing team. In some cases, a team may have

their own community-driven sources of help or recruitment such as an Internet forum.

The points can foster friendly competition between individuals and

teams to compute the most for the project, which can benefit the folding

community and accelerate scientific research. Individual and team statistics are posted on the Folding@home website.

If a user does not form a new team, or does not join an existing

team, that user automatically becomes part of a "Default" team. This

"Default" team has a team number of "0". Statistics are accumulated for

this "Default" team as well as for specially named teams.

Software

Folding@home software at the user's end involves three primary components: work units, cores, and a client.

Work units

A

work unit is the protein data that the client is asked to process. Work

units are a fraction of the simulation between the states in a Markov model.

After the work unit has been downloaded and completely processed by a

volunteer's computer, it is returned to Folding@home servers, which then

award the volunteer the credit points. This cycle repeats

automatically.

All work units have associated deadlines, and if this deadline is

exceeded, the user may not get credit and the unit will be automatically

reissued to another participant. As protein folding occurs serially,

and many work units are generated from their predecessors, this allows

the overall simulation process to proceed normally if a work unit is not

returned after a reasonable period of time. Due to these deadlines, the

minimum system requirement for Folding@home is a Pentium 3 450 MHz CPU

with Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE).

However, work units for high-performance clients have a much shorter

deadline than those for the uniprocessor client, as a major part of the

scientific benefit is dependent on rapidly completing simulations.

Before public release, work units go through several quality assurance

steps to keep problematic ones from becoming fully available. These

testing stages include internal, beta, and advanced, before a final full

release across Folding@home.

Folding@home's work units are normally processed only once, except in

the rare event that errors occur during processing. If this occurs for

three different users, the unit is automatically pulled from

distribution.

The Folding@home support forum can be used to differentiate between

issues arising from problematic hardware and bad work units.

Cores

Specialized molecular dynamics programs, referred to as "FahCores"

and often abbreviated "cores", perform the calculations on the work unit

as a background process. A large majority of Folding@home's cores are based on GROMACS, one of the fastest and most popular molecular dynamics software packages, which largely consists of manually optimized assembly language code and hardware optimizations. Although GROMACS is open-source software and there is a cooperative effort between the Pande lab and GROMACS developers, Folding@home uses a closed-source license to help ensure data validity. Less active cores include ProtoMol and SHARPEN. Folding@home has used AMBER, CPMD, Desmond, and TINKER, but these have since been retired and are no longer in active service. Some of these cores perform explicit solvation calculations in which the surrounding solvent (usually water) is modeled atom-by-atom; while others perform implicit solvation methods, where the solvent is treated as a mathematical continuum.

The core is separate from the client to enable the scientific methods

to be updated automatically without requiring a client update. The cores

periodically create calculation checkpoints so that if they are interrupted they can resume work from that point upon startup.

Client

Folding@Home running on Fedora 25

A Folding@home participant installs a client program on their personal computer.

The user interacts with the client, which manages the other software

components in the background. Through the client, the user may pause the

folding process, open an event log, check the work progress, or view

personal statistics. The computer clients run continuously in the background at a very low priority, using idle processing power so that normal computer use is unaffected. The maximum CPU use can be adjusted via client settings. The client connects to a Folding@home server

and retrieves a work unit and may also download the appropriate core

for the client's settings, operating system, and the underlying hardware

architecture. After processing, the work unit is returned to the

Folding@home servers. Computer clients are tailored to uniprocessor and multi-core processor systems, and graphics processing units. The diversity and power of each hardware architecture

provides Folding@home with the ability to efficiently complete many

types of simulations in a timely manner (in a few weeks or months rather

than years), which is of significant scientific value. Together, these

clients allow researchers to study biomedical questions formerly

considered impractical to tackle computationally.

Professional software developers are responsible for most of

Folding@home's code, both for the client and server-side. The

development team includes programmers from Nvidia, ATI, Sony, and

Cauldron Development.

Clients can be downloaded only from the official Folding@home website

or its commercial partners, and will only interact with Folding@home

computer files. They will upload and download data with Folding@home's

data servers (over port 8080, with 80 as an alternate), and the communication is verified using 2048-bit digital signatures. While the client's graphical user interface (GUI) is open-source, the client is proprietary software citing security and scientific integrity as the reasons.

However, this rationale of using proprietary software is disputed

since while the license could be enforceable in the legal domain

retrospectively, it doesn't practically prevent the modification (also

known as patching) of the executable binary files. Likewise, binary-only distribution does not prevent the malicious modification of executable binary-code, either through a man-in-the-middle attack while being downloaded via the internet, or by the redistribution of binaries by a third-party that have been previously modified either in their binary state (i.e. patched), or by decompiling and recompiling them after modification. These modifications are possible unless the binary files – and the transport channel – are signed

and the recipient person/system is able to verify the digital

signature, in which case unwarranted modifications should be detectable,

but not always.

Either way, since in the case of Folding@home the input data and output

result processed by the client-software are both digitally signed, the integrity of work can be verified independently from the integrity of the client software itself.

Folding@home uses the Cosm software libraries for networking. Folding@home was launched on October 1, 2000, and was the first distributed computing project aimed at bio-molecular systems. Its first client was a screensaver, which would run while the computer was not otherwise in use. In 2004, the Pande lab collaborated with David P. Anderson to test a supplemental client on the open-source BOINC framework. This client was released to closed beta in April 2005; however, the method became unworkable and was shelved in June 2006.

Graphics processing units

The specialized hardware of graphics processing units

(GPU) is designed to accelerate rendering of 3-D graphics applications

such as video games and can significantly outperform CPUs for some types

of calculations. GPUs are one of the most powerful and rapidly growing

computing platforms, and many scientists and researchers are pursuing general-purpose computing on graphics processing units

(GPGPU). However, GPU hardware is difficult to use for non-graphics

tasks and usually requires significant algorithm restructuring and an

advanced understanding of the underlying architecture. Such customization is challenging, more so to researchers with limited software development resources. Folding@home uses the open-source OpenMM library, which uses a bridge design pattern with two application programming interface

(API) levels to interface molecular simulation software to an

underlying hardware architecture. With the addition of hardware

optimizations, OpenMM-based GPU simulations need no significant

modification but achieve performance nearly equal to hand-tuned GPU

code, and greatly outperform CPU implementations.

Before 2010, the computing reliability of GPGPU consumer-grade

hardware was largely unknown, and circumstantial evidence related to the

lack of built-in error detection and correction

in GPU memory raised reliability concerns. In the first large-scale

test of GPU scientific accuracy, a 2010 study of over 20,000 hosts on

the Folding@home network detected soft errors

in the memory subsystems of two-thirds of the tested GPUs. These errors

strongly correlated to board architecture, though the study concluded

that reliable GPU computing was very feasible as long as attention is

paid to the hardware traits, such as software-side error detection.

The first generation of Folding@home's GPU client (GPU1) was released to the public on October 2, 2006, delivering a 20–30 times speedup for some calculations over its CPU-based GROMACS counterparts. It was the first time GPUs had been used for either distributed computing or major molecular dynamics calculations. GPU1 gave researchers significant knowledge and experience with the development of GPGPU software, but in response to scientific inaccuracies with DirectX, on April 10, 2008 it was succeeded by GPU2, the second generation of the client. Following the introduction of GPU2, GPU1 was officially retired on June 6. Compared to GPU1, GPU2 was more scientifically reliable and productive, ran on ATI and CUDA-enabled Nvidia GPUs, and supported more advanced algorithms, larger proteins, and real-time visualization of the protein simulation. Following this, the third generation of Folding@home's GPU client (GPU3) was released on May 25, 2010. While backward compatible with GPU2, GPU3 was more stable, efficient, and flexibile in its scientific abilities, and used OpenMM on top of an OpenCL framework. Although these GPU3 clients did not natively support the operating systems Linux and macOS, Linux users with Nvidia graphics cards were able to run them through the Wine software application. GPUs remain Folding@home's most powerful platform in FLOPS. As of November 2012, GPU clients account for 87% of the entire project's x86 FLOPS throughput.

Native support for Nvidia and AMD graphics cards under Linux was introduced with FahCore 17, which uses OpenCL rather than CUDA.

PlayStation 3

The PlayStation 3's Life With PlayStation client displays a 3-D animation of the protein being folded

From March 2007 until November 2012, Folding@home took advantage of the computing power of PlayStation 3s. At the time of its inception, its main streaming Cell processor

delivered a 20 times speed increase over PCs for some calculations,

processing power which could not be found on other systems such as the Xbox 360. The PS3's high speed and efficiency introduced other opportunities for worthwhile optimizations according to Amdahl's law,

and significantly changed the tradeoff between computing efficiency and

overall accuracy, allowing the use of more complex molecular models at

little added computing cost. This allowed Folding@home to run biomedical calculations that would have been otherwise infeasible computationally.

The PS3 client was developed in a collaborative effort between Sony and the Pande lab and was first released as a standalone client on March 23, 2007. Its release made Folding@home the first distributed computing project to use PS3s. On September 18 of the following year, the PS3 client became a channel of Life with PlayStation on its launch.

In the types of calculations it can perform, at the time of its

introduction, the client fit in between a CPU's flexibility and a GPU's

speed. However, unlike clients running on personal computers, users were unable to perform other activities on their PS3 while running Folding@home. The PS3's uniform console environment made technical support easier and made Folding@home more user friendly.

The PS3 also had the ability to stream data quickly to its GPU, which

was used for real-time atomic-level visualizing of the current protein

dynamics.

On November 6, 2012, Sony ended support for the Folding@home PS3

client and other services available under Life with PlayStation. Over

its lifetime of five years and seven months, more than 15 million users

contributed over 100 million hours of computing to Folding@home, greatly

assisting the project with disease research. Following discussions with

the Pande lab, Sony decided to terminate the application. Pande

considered the PlayStation 3 client a "game changer" for the project.

Multi-core processing client

Folding@home can use the parallel computing

abilities of modern multi-core processors. The ability to use several

CPU cores simultaneously allows completing the full simulation far

faster. Working together, these CPU cores complete single work units

proportionately faster than the standard uniprocessor client. This

method is scientifically valuable because it enables much longer

simulation trajectories to be performed in the same amount of time, and

reduces the traditional difficulties of scaling a large simulation to

many separate processors. A 2007 publication in the Journal of Molecular Biology relied on multi-core processing to simulate the folding of part of the villin

protein approximately 10 times longer than was possible with a

single-processor client, in agreement with experimental folding rates.

In November 2006, first-generation symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) clients were publicly released for open beta testing, referred to as SMP1. These clients used Message Passing Interface (MPI) communication protocols for parallel processing, as at that time the GROMACS cores were not designed to be used with multiple threads. This was the first time a distributed computing project had used MPI. Although the clients performed well in Unix-based operating systems such as Linux and macOS, they were troublesome under Windows.

On January 24, 2010, SMP2, the second generation of the SMP clients and

the successor to SMP1, was released as an open beta and replaced the

complex MPI with a more reliable thread-based implementation.

SMP2 supports a trial of a special category of bigadv work

units, designed to simulate proteins that are unusually large and

computationally intensive and have a great scientific priority. These

units originally required a minimum of eight CPU cores, which was raised to sixteen later, on February 7, 2012. Along with these added hardware requirements over standard SMP2 work units, they require more system resources such as random-access memory (RAM) and Internet bandwidth. In return, users who run these are rewarded with a 20% increase over SMP2's bonus point system.

The bigadv category allows Folding@home to run especially demanding

simulations for long times that had formerly required use of

supercomputing clusters and could not be performed anywhere else on Folding@home.

Many users with hardware able to run bigadv units have later had their

hardware setup deemed ineligible for bigadv work units when CPU core

minimums were increased, leaving them only able to run the normal SMP

work units. This frustrated many users who invested significant amounts

of money into the program only to have their hardware be obsolete for

bigadv purposes shortly after. As a result, Pande announced in January

2014 that the bigadv program would end on January 31, 2015.

V7

A sample image of the V7 client in Novice mode running under Windows 7.

In addition to a variety of controls and user details, V7 presents work

unit information, such as its state, calculation progress, ETA, credit

points, identification numbers, and description.

The V7 client is the seventh and latest generation of the

Folding@home client software, and is a full rewrite and unification of

the prior clients for Windows, macOS, and Linux operating systems. It was released on March 22, 2012. Like its predecessors, V7 can run Folding@home in the background at a very low priority,

allowing other applications to use CPU resources as they need. It is

designed to make the installation, start-up, and operation more

user-friendly for novices, and offer greater scientific flexibility to

researchers than prior clients. V7 uses Trac for managing its bug tickets so that users can see its development process and provide feedback.

V7 consists of four integrated elements. The user typically interacts with V7's open-source GUI, named FAHControl.

This has Novice, Advanced, and Expert user interface modes, and has the

ability to monitor, configure, and control many remote folding clients

from one computer. FAHControl directs FAHClient, a back-end application that in turn manages each FAHSlot (or slot).

Each slot acts as replacement for the formerly distinct Folding@home v6

uniprocessor, SMP, or GPU computer clients, as it can download,

process, and upload work units independently. The FAHViewer function,

modeled after the PS3's viewer, displays a real-time 3-D rendering, if

available, of the protein currently being processed.

Google Chrome

In 2014, a client for the Google Chrome and Chromium web browsers was released, allowing users to run Folding@home in their web browser. The client used Google's Native Client (NaCl) feature on Chromium-based web browsers to run the Folding@home code at near-native speed in a sandbox on the user's machine. Due to the phasing out of NaCL and changes at Folding@home, the web client was permanently shut down in June 2019.

Android

In July 2015, a client for Android mobile phones was released on Google Play for devices running Android 4.4 KitKat or newer.

On February 16, 2018 the Android client, which was offered in cooperation with Sony, was removed from the Google Play. Plans were announced to offer an open source alternative in the future.

Comparison to other molecular simulators

Rosetta@home is a distributed computing project aimed at protein structure prediction and is one of the most accurate tertiary structure predictors. The conformational states from Rosetta's software can be used to

initialize a Markov state model as starting points for Folding@home

simulations.

Conversely, structure prediction algorithms can be improved from

thermodynamic and kinetic models and the sampling aspects of protein

folding simulations.

As Rosetta only tries to predict the final folded state, and not how

folding proceeds, Rosetta@home and Folding@home are complementary and

address very different molecular questions.

Anton

is a special-purpose supercomputer built for molecular dynamics

simulations. In October 2011, Anton and Folding@home were the two most

powerful molecular dynamics systems. Anton is unique in its ability to produce single ultra-long computationally costly molecular trajectories, such as one in 2010 which reached the millisecond range. These long trajectories may be especially helpful for some types of biochemical problems. However, Anton does not use Markov state models (MSM) for analysis. In 2011, the Pande lab constructed a MSM from two 100-µs

Anton simulations and found alternative folding pathways that were not

visible through Anton's traditional analysis. They concluded that there

was little difference between MSMs constructed from a limited number of

long trajectories or one assembled from many shorter trajectories.

In June 2011 Folding@home added sampling of an Anton simulation in an

effort to better determine how its methods compare to Anton's.

However, unlike Folding@home's shorter trajectories, which are more

amenable to distributed computing and other parallelizing methods,

longer trajectories do not require adaptive sampling to sufficiently

sample the protein's phase space.

Due to this, it is possible that a combination of Anton's and

Folding@home's simulation methods would provide a more thorough sampling

of this space.