Educational psychology is the branch of psychology concerned with the scientific study of human learning. The study of learning processes, from both cognitive and behavioral perspectives, allows researchers to understand individual differences in intelligence, cognitive development, affect, motivation, self-regulation, and self-concept, as well as their role in learning. The field of educational psychology relies heavily on quantitative methods, including testing and measurement, to enhance educational activities related to instructional design, classroom management, and assessment, which serve to facilitate learning processes in various educational settings across the lifespan.

Educational psychology can in part be understood through its relationship with other disciplines. It is informed primarily by psychology, bearing a relationship to that discipline analogous to the relationship between medicine and biology. It is also informed by neuroscience. Educational psychology in turn informs a wide range of specialities within educational studies, including instructional design, educational technology, curriculum development, organizational learning, special education, classroom management, and student motivation. Educational psychology both draws from and contributes to cognitive science and the learning sciences. In universities, departments of educational psychology are usually housed within faculties of education, possibly accounting for the lack of representation of educational psychology content in introductory psychology textbooks.

The field of educational psychology involves the study of memory, conceptual processes, and individual differences (via cognitive psychology) in conceptualizing new strategies for learning processes in humans. Educational psychology has been built upon theories of operant conditioning, functionalism, structuralism, constructivism, humanistic psychology, Gestalt psychology, and information processing.

Educational psychology has seen rapid growth and development as a profession in the last twenty years. School psychology began with the concept of intelligence testing leading to provisions for special education students, who could not follow the regular classroom curriculum in the early part of the 20th century. However, "school psychology" itself has built a fairly new profession based upon the practices and theories of several psychologists among many different fields. Educational psychologists are working side by side with psychiatrists, social workers, teachers, speech and language therapists, and counselors in an attempt to understand the questions being raised when combining behavioral, cognitive, and social psychology in the classroom setting.

History

Early years

Educational psychology is a fairly new and growing field of study. Although it can date back as early as the days of Plato and Aristotle, educational psychology was not considered a specific practice. It was unknown that everyday teaching and learning in which individuals had to think about individual differences, assessment, development, the nature of a subject being taught, problem-solving, and transfer of learning was the beginning to the field of educational psychology. These topics are important to education and, as a result, they are important in understanding human cognition, learning, and social perception.

Plato and Aristotle

Educational psychology dates back to the time of Aristotle and Plato. Plato and Aristotle researched individual differences in the field of education, training of the body and the cultivation of psycho-motor skills, the formation of good character, the possibilities and limits of moral education. Some other educational topics they spoke about were the effects of music, poetry, and the other arts on the development of individual, role of teacher, and the relations between teacher and student. Plato saw knowledge acquisition as an innate ability, which evolves through experience and understanding of the world. This conception of human cognition has evolved into a continuing argument of nature vs. nurture in understanding conditioning and learning today. Aristotle observed the phenomenon of "association." His four laws of association included succession, contiguity, similarity, and contrast. His studies examined recall and facilitated learning processes.

John Locke

John Locke is considered one of the most influential philosophers in post-renaissance Europe, a time period that began around the mid-1600s. Locke is considered the "Father of English Psychology". One of Locke's most important works was written in 1690, named An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In this essay, he introduced the term "tabula rasa" meaning "blank slate." Locke explained that learning was attained through experience only and that we are all born without knowledge.

He followed by contrasting Plato's theory of innate learning processes. Locke believed the mind was formed by experiences, not innate ideas. Locke introduced this idea as "empiricism," or the understanding that knowledge is only built on knowledge and experience.

In the late 1600s, John Locke advanced the hypothesis that people learn primarily from external forces. He believed that the mind was like a blank tablet (tabula rasa), and that successions of simple impressions give rise to complex ideas through association and reflection. Locke is credited with establishing "empiricism" as a criterion for testing the validity of knowledge, thus providing a conceptual framework for later development of experimental methodology in the natural and social sciences.

Before 1890

Philosophers of education such as Juan Vives, Johann Pestalozzi, Friedrich Fröbel, and Johann Herbart had examined, classified and judged the methods of education centuries before the beginnings of psychology in the late 1800s.

Juan Vives

Juan Vives (1493–1540) proposed induction as the method of study and believed in the direct observation and investigation of the study of nature. His studies focused on humanistic learning, which opposed scholasticism and was influenced by a variety of sources including philosophy, psychology, politics, religion, and history. He was one of the first prominent thinkers to emphasize that the location of a school is important to learning. He suggested that a school should be located away from disturbing noises; the air quality should be good and there should be plenty of food for the students and teachers.[9] Vives emphasized the importance of understanding individual differences of the students and suggested practice as an important tool for learning.

Vives introduced his educational ideas in his writing, "De anima et vita" in 1538. In this publication, Vives explores moral philosophy as a setting for his educational ideals; with this, he explains that the different parts of the soul (similar to that of Aristotle's ideas) are each responsible for different operations, which function distinctively. The first book covers the different "souls": "The Vegetative Soul;" this is the soul of nutrition, growth, and reproduction, "The Sensitive Soul," which involves the five external senses; "The Cogitative soul," which includes internal senses and cognitive facilities. The second book involves functions of the rational soul: mind, will, and memory. Lastly, the third book explains the analysis of emotions.

Johann Pestalozzi

Johann Pestalozzi (1746–1827), a Swiss educational reformer, emphasized the child rather than the content of the school. Pestalozzi fostered an educational reform backed by the idea that early education was crucial for children, and could be manageable for mothers. Eventually, this experience with early education would lead to a "wholesome person characterized by morality." Pestalozzi has been acknowledged for opening institutions for education, writing books for mother's teaching home education, and elementary books for students, mostly focusing on the kindergarten level. In his later years, he published teaching manuals and methods of teaching.

During the time of The Enlightenment, Pestalozzi's ideals introduced "educationalization". This created the bridge between social issues and education by introducing the idea of social issues to be solved through education. Horlacher describes the most prominent example of this during The Enlightenment to be "improving agricultural production methods."

Johann Herbart

Johann Herbart (1776–1841) is considered the father of educational psychology. He believed that learning was influenced by interest in the subject and the teacher. He thought that teachers should consider the students' existing mental sets—what they already know—when presenting new information or material. Herbart came up with what are now known as the formal steps. The 5 steps that teachers should use are:

- Review material that has already been learned by the student

- Prepare the student for new material by giving them an overview of what they are learning next

- Present the new material.

- Relate the new material to the old material that has already been learned.

- Show how the student can apply the new material and show the material they will learn next.

1890–1920

There were three major figures in educational psychology in this period: William James, G. Stanley Hall, and John Dewey. These three men distinguished themselves in general psychology and educational psychology, which overlapped significantly at the end of the 19th century.

William James (1842–1910)

The period of 1890–1920 is considered the golden era of educational psychology when aspirations of the new discipline rested on the application of the scientific methods of observation and experimentation to educational problems. From 1840 to 1920 37 million people immigrated to the United States. This created an expansion of elementary schools and secondary schools. The increase in immigration also provided educational psychologists the opportunity to use intelligence testing to screen immigrants at Ellis Island. Darwinism influenced the beliefs of the prominent educational psychologists. Even in the earliest years of the discipline, educational psychologists recognized the limitations of this new approach. The pioneering American psychologist William James commented that:

Psychology is a science, and teaching is an art; and sciences never generate arts directly out of themselves. An intermediate inventive mind must make that application, by using its originality".

James is the father of psychology in America but he also made contributions to educational psychology. In his famous series of lectures Talks to Teachers on Psychology, published in 1899, James defines education as "the organization of acquired habits of conduct and tendencies to behavior". He states that teachers should "train the pupil to behavior" so that he fits into the social and physical world. Teachers should also realize the importance of habit and instinct. They should present information that is clear and interesting and relate this new information and material to things the student already knows about. He also addresses important issues such as attention, memory, and association of ideas.

Alfred Binet

Alfred Binet published Mental Fatigue in 1898, in which he attempted to apply the experimental method to educational psychology. In this experimental method he advocated for two types of experiments, experiments done in the lab and experiments done in the classroom. In 1904 he was appointed the Minister of Public Education. This is when he began to look for a way to distinguish children with developmental disabilities. Binet strongly supported special education programs because he believed that "abnormality" could be cured. The Binet-Simon test was the first intelligence test and was the first to distinguish between "normal children" and those with developmental disabilities. Binet believed that it was important to study individual differences between age groups and children of the same age. He also believed that it was important for teachers to take into account individual students' strengths and also the needs of the classroom as a whole when teaching and creating a good learning environment. He also believed that it was important to train teachers in observation so that they would be able to see individual differences among children and adjust the curriculum to the students. Binet also emphasized that practice of material was important. In 1916 Lewis Terman revised the Binet-Simon so that the average score was always 100. The test became known as the Stanford-Binet and was one of the most widely used tests of intelligence. Terman, unlike Binet, was interested in using intelligence test to identify gifted children who had high intelligence. In his longitudinal study of gifted children, who became known as the Termites, Terman found that gifted children become gifted adults.

Edward Thorndike

Edward Thorndike (1874–1949) supported the scientific movement in education. He based teaching practices on empirical evidence and measurement. Thorndike developed the theory of instrumental conditioning or the law of effect. The law of effect states that associations are strengthened when it is followed by something pleasing and associations are weakened when followed by something not pleasing. He also found that learning is done a little at a time or in increments, learning is an automatic process and its principles apply to all mammals. Thorndike's research with Robert Woodworth on the theory of transfer found that learning one subject will only influence your ability to learn another subject if the subjects are similar. This discovery led to less emphasis on learning the classics because they found that studying the classics does not contribute to overall general intelligence. Thorndike was one of the first to say that individual differences in cognitive tasks were due to how many stimulus-response patterns a person had rather than general intellectual ability. He contributed word dictionaries that were scientifically based to determine the words and definitions used. The dictionaries were the first to take into consideration the users' maturity level. He also integrated pictures and easier pronunciation guide into each of the definitions. Thorndike contributed arithmetic books based on learning theory. He made all the problems more realistic and relevant to what was being studied, not just to improve the general intelligence. He developed tests that were standardized to measure performance in school-related subjects. His biggest contribution to testing was the CAVD intelligence test which used a multidimensional approach to intelligence and was the first to use a ratio scale. His later work was on programmed instruction, mastery learning, and computer-based learning:

If, by a miracle of mechanical ingenuity, a book could be so arranged that only to him who had done what was directed on page one would page two become visible, and so on, much that now requires personal instruction could be managed by print.

John Dewey

John Dewey (1859–1952) had a major influence on the development of progressive education in the United States. He believed that the classroom should prepare children to be good citizens and facilitate creative intelligence. He pushed for the creation of practical classes that could be applied outside of a school setting. He also thought that education should be student-oriented, not subject-oriented. For Dewey, education was a social experience that helped bring together generations of people. He stated that students learn by doing. He believed in an active mind that was able to be educated through observation, problem-solving, and enquiry. In his 1910 book How We Think, he emphasizes that material should be provided in a way that is stimulating and interesting to the student since it encourages original thought and problem-solving. He also stated that material should be relative to the student's own experience.

"The material furnished by way of information should be relevant to a question that is vital in the students own experience"

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) was one of the most powerful researchers in the area of developmental psychology during the 20th century. He developed the theory of cognitive development. The theory stated that intelligence developed in four different stages. The stages are the sensorimotor stage from birth to 2 years old, the preoperational state from 2 to 7 years old, the concrete operational stage from 7 to 10 years old, and the formal operational stage from 12 years old and up. He also believed that learning was constrained to the child's cognitive development. Piaget influenced educational psychology because he was the first to believe that cognitive development was important and something that should be paid attention to in education. Most of the research on Piagetian theory was carried out by American educational psychologists.

1920–present

The number of people receiving a high school and college education increased dramatically from 1920 to 1960. Because very few jobs were available to teens coming out of eighth grade, there was an increase in high school attendance in the 1930s. The progressive movement in the United States took off at this time and led to the idea of progressive education. John Flanagan, an educational psychologist, developed tests for combat trainees and instructions in combat training. In 1954 the work of Kenneth Clark and his wife on the effects of segregation on black and white children was influential in the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education. From the 1960s to present day, educational psychology has switched from a behaviorist perspective to a more cognitive-based perspective because of the influence and development of cognitive psychology at this time.

Jerome Bruner

Jerome Bruner is notable for integrating Piaget's cognitive approaches into educational psychology. He advocated for discovery learning where teachers create a problem solving environment that allows the student to question, explore and experiment. In his book The Process of Education Bruner stated that the structure of the material and the cognitive abilities of the person are important in learning. He emphasized the importance of the subject matter. He also believed that how the subject was structured was important for the student's understanding of the subject and that it was the goal of the teacher to structure the subject in a way that was easy for the student to understand. In the early 1960s, Bruner went to Africa to teach math and science to school children, which influenced his view as schooling as a cultural institution. Bruner was also influential in the development of MACOS, Man: a Course of Study, which was an educational program that combined anthropology and science. The program explored human evolution and social behavior. He also helped with the development of the head start program. He was interested in the influence of culture on education and looked at the impact of poverty on educational development.

Benjamin Bloom

Benjamin Bloom (1903–1999) spent over 50 years at the University of Chicago, where he worked in the department of education. He believed that all students can learn. He developed the taxonomy of educational objectives. The objectives were divided into three domains: cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. The cognitive domain deals with how we think. It is divided into categories that are on a continuum from easiest to more complex. The categories are knowledge or recall, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. The affective domain deals with emotions and has 5 categories. The categories are receiving phenomenon, responding to that phenomenon, valuing, organization, and internalizing values. The psychomotor domain deals with the development of motor skills, movement, and coordination and has 7 categories that also go from simplest to most complex. The 7 categories of the psychomotor domain are perception, set, guided response, mechanism, complex overt response, adaptation, and origination. The taxonomy provided broad educational objectives that could be used to help expand the curriculum to match the ideas in the taxonomy. The taxonomy is considered to have a greater influence internationally than in the United States. Internationally, the taxonomy is used in every aspect of education from the training of the teachers to the development of testing material. Bloom believed in communicating clear learning goals and promoting an active student. He thought that teachers should provide feedback to the students on their strengths and weaknesses. Bloom also did research on college students and their problem-solving processes. He found that they differ in understanding the basis of the problem and the ideas in the problem. He also found that students differ in process of problem-solving in their approach and attitude toward the problem.

Nathaniel Gage

Nathaniel Gage (1917-2008) is an important figure in educational psychology as his research focused on improving teaching and understanding the processes involved in teaching. He edited the book Handbook of Research on Teaching (1963), which helped develop early research in teaching and educational psychology. Gage founded the Stanford Center for Research and Development in Teaching, which contributed research on teaching as well as influencing the education of important educational psychologists.

Perspectives

Behavioral

Applied behavior analysis, a research-based science utilizing behavioral principles of operant conditioning, is effective in a range of educational settings. For example, teachers can alter student behavior by systematically rewarding students who follow classroom rules with praise, stars, or tokens exchangeable for sundry items. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of awards in changing behavior, their use in education has been criticized by proponents of self-determination theory, who claim that praise and other rewards undermine intrinsic motivation. There is evidence that tangible rewards decrease intrinsic motivation in specific situations, such as when the student already has a high level of intrinsic motivation to perform the goal behavior. But the results showing detrimental effects are counterbalanced by evidence that, in other situations, such as when rewards are given for attaining a gradually increasing standard of performance, rewards enhance intrinsic motivation. Many effective therapies have been based on the principles of applied behavior analysis, including pivotal response therapy which is used to treat autism spectrum disorders.

Cognitive

Among current educational psychologists, the cognitive perspective is more widely held than the behavioral perspective, perhaps because it admits causally related mental constructs such as traits, beliefs, memories, motivations, and emotions. Cognitive theories claim that memory structures determine how information is perceived, processed, stored, retrieved and forgotten. Among the memory structures theorized by cognitive psychologists are separate but linked visual and verbal systems described by Allan Paivio's dual coding theory. Educational psychologists have used dual coding theory and cognitive load theory to explain how people learn from multimedia presentations.

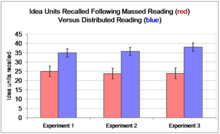

The spaced learning effect, a cognitive phenomenon strongly supported by psychological research, has broad applicability within education. For example, students have been found to perform better on a test of knowledge about a text passage when a second reading of the passage is delayed rather than immediate (see figure). Educational psychology research has confirmed the applicability to the education of other findings from cognitive psychology, such as the benefits of using mnemonics for immediate and delayed retention of information.

Problem solving, according to prominent cognitive psychologists, is fundamental to learning. It resides as an important research topic in educational psychology. A student is thought to interpret a problem by assigning it to a schema retrieved from long-term memory. A problem students run into while reading is called "activation." This is when the student's representations of the text are present during working memory. This causes the student to read through the material without absorbing the information and being able to retain it. When working memory is absent from the reader's representations of the working memory they experience something called "deactivation." When deactivation occurs, the student has an understanding of the material and is able to retain information. If deactivation occurs during the first reading, the reader does not need to undergo deactivation in the second reading. The reader will only need to reread to get a "gist" of the text to spark their memory. When the problem is assigned to the wrong schema, the student's attention is subsequently directed away from features of the problem that are inconsistent with the assigned schema. The critical step of finding a mapping between the problem and a pre-existing schema is often cited as supporting the centrality of analogical thinking to problem-solving.

Cognitive view of intelligence

Each person has an individual profile of characteristics, abilities, and challenges that result from predisposition, learning, and development. These manifest as individual differences in intelligence, creativity, cognitive style, motivation, and the capacity to process information, communicate, and relate to others. The most prevalent disabilities found among school age children are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disability, dyslexia, and speech disorder. Less common disabilities include intellectual disability, hearing impairment, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and blindness.

Although theories of intelligence have been discussed by philosophers since Plato, intelligence testing is an invention of educational psychology, and is coincident with the development of that discipline. Continuing debates about the nature of intelligence revolve on whether it can be characterized by a single factor known as general intelligence, multiple factors (e.g., Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences), or whether it can be measured at all. In practice, standardized instruments such as the Stanford-Binet IQ test and the WISC are widely used in economically developed countries to identify children in need of individualized educational treatment. Children classified as gifted are often provided with accelerated or enriched programs. Children with identified deficits may be provided with enhanced education in specific skills such as phonological awareness. In addition to basic abilities, the individual's personality traits are also important, with people higher in conscientiousness and hope attaining superior academic achievements, even after controlling for intelligence and past performance.

Developmental

Developmental psychology, and especially the psychology of cognitive development, opens a special perspective for educational psychology. This is so because education and the psychology of cognitive development converge on a number of crucial assumptions. First, the psychology of cognitive development defines human cognitive competence at successive phases of development. Education aims to help students acquire knowledge and develop skills that are compatible with their understanding and problem-solving capabilities at different ages. Thus, knowing the students' level on a developmental sequence provides information on the kind and level of knowledge they can assimilate, which, in turn, can be used as a frame for organizing the subject matter to be taught at different school grades. This is the reason why Piaget's theory of cognitive development was so influential for education, especially mathematics and science education. In the same direction, the neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development suggest that in addition to the concerns above, sequencing of concepts and skills in teaching must take account of the processing and working memory capacities that characterize successive age levels.

Second, the psychology of cognitive development involves understanding how cognitive change takes place and recognizing the factors and processes which enable cognitive competence to develop. Education also capitalizes on cognitive change, because the construction of knowledge presupposes effective teaching methods that would move the student from a lower to a higher level of understanding. Mechanisms such as reflection on actual or mental actions vis-à-vis alternative solutions to problems, tagging new concepts or solutions to symbols that help one recall and mentally manipulate them are just a few examples of how mechanisms of cognitive development may be used to facilitate learning.

Finally, the psychology of cognitive development is concerned with individual differences in the organization of cognitive processes and abilities, in their rate of change, and in their mechanisms of change. The principles underlying intra- and inter-individual differences could be educationally useful, because knowing how students differ in regard to the various dimensions of cognitive development, such as processing and representational capacity, self-understanding and self-regulation, and the various domains of understanding, such as mathematical, scientific, or verbal abilities, would enable the teacher to cater for the needs of the different students so that no one is left behind.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a category of learning theory in which emphasis is placed on the agency and prior "knowing" and experience of the learner, and often on the social and cultural determinants of the learning process. Educational psychologists distinguish individual (or psychological) constructivism, identified with Piaget's theory of cognitive development, from social constructivism. The social constructivist paradigm views the context in which the learning occurs as central to the learning itself. It regards learning as a process of enculturation. People learn by exposure to the culture of practitioners. They observe and practice the behavior of practitioners and 'pick up relevant jargon, imitate behavior, and gradually start to act in accordance with the norms of the practice'. So, a student learns to become a mathematician through exposure to mathematician using tools to solve mathematical problems. So in order to master a particular domain of knowledge it is not enough for students to learn the concepts of the domain. They should be exposed to the use of the concepts in authentic activities by the practitioners of the domain.

A dominant influence on the social constructivist paradigm is Lev Vygotsky's work on sociocultural learning, describing how interactions with adults, more capable peers, and cognitive tools are internalized to form mental constructs. "Zone of Proximal Development" (ZPD) is a term Vygotsky used to characterize an individual's mental development. He believed the task individuals can do on their own do not give a complete understanding of their mental development. He originally defined the ZPD as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” He cited a famous example to make his case. Two children in school who originally can solve problems at an eight-year-old developmental level (that is, typical for children who were age 8), might be at different developmental levels. If each child received assistance from an adult, one was able to perform at a nine-year-old level and one was able to perform at a twelve-year-old level. He said “This difference between twelve and eight, or between nine and eight, is what we call the zone of proximal development.” He further said that the ZPD “defines those functions that have not yet matured but are in the process of maturation, functions that will mature tomorrow but are currently in an embryonic state.” The zone is bracketed by the learner's current ability and the ability they can achieve with the aid of an instructor of some capacity.

Vygotsky viewed the ZPD as a better way to explain the relation between children's learning and cognitive development. Prior to the ZPD, the relation between learning and development could be boiled down to the following three major positions: 1) Development always precedes learning (e.g., constructivism): children first need to meet a particular maturation level before learning can occur; 2) Learning and development cannot be separated, but instead occur simultaneously (e.g., behaviorism): essentially, learning is development; and 3) learning and development are separate, but interactive processes (e.g., gestaltism): one process always prepares the other process, and vice versa. Vygotsky rejected these three major theories because he believed that learning should always precede development in the ZPD. According to Vygotsky, through the assistance of a more knowledgeable other, a child is able to learn skills or aspects of a skill that go beyond the child's actual developmental or maturational level. The lower limit of ZPD is the level of skill reached by the child working independently (also referred to as the child's developmental level). The upper limit is the level of potential skill that the child is able to reach with the assistance of a more capable instructor. In this sense, the ZPD provides a prospective view of cognitive development, as opposed to a retrospective view that characterizes development in terms of a child's independent capabilities. The advancement through and attainment of the upper limit of the ZPD is limited by the instructional and scaffolding-related capabilities of the more knowledgeable other (MKO). The MKO is typically assumed to be an older, more experienced teacher or parent, but often can be a learner's peer or someone their junior. The MKO need not even be a person, it can be a machine or book, or other source of visual and/or audio input.

Elaborating on Vygotsky's theory, Jerome Bruner and other educational psychologists developed the important concept of instructional scaffolding, in which the social or information environment offers supports for learning that are gradually withdrawn as they become internalized.

Jean Piaget's Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget was interested in how an organism adapts to its environment. Piaget hypothesized that infants are born with a schema operating at birth that he called "reflexes". Piaget identified four stages in cognitive development. The four stages are sensorimotor stage, pre-operational stage, concrete operational stage, and formal operational stage.

Conditioning and learning

To understand the characteristics of learners in childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age, educational psychology develops and applies theories of human development. Often represented as stages through which people pass as they mature, developmental theories describe changes in mental abilities (cognition), social roles, moral reasoning, and beliefs about the nature of knowledge.

For example, educational psychologists have conducted research on the instructional applicability of Jean Piaget's theory of development, according to which children mature through four stages of cognitive capability. Piaget hypothesized that children are not capable of abstract logical thought until they are older than about 11 years, and therefore younger children need to be taught using concrete objects and examples. Researchers have found that transitions, such as from concrete to abstract logical thought, do not occur at the same time in all domains. A child may be able to think abstractly about mathematics, but remain limited to concrete thought when reasoning about human relationships. Perhaps Piaget's most enduring contribution is his insight that people actively construct their understanding through a self-regulatory process.

Piaget proposed a developmental theory of moral reasoning in which children progress from a naïve understanding of morality based on behavior and outcomes to a more advanced understanding based on intentions. Piaget's views of moral development were elaborated by Lawrence Kohlberg into a stage theory of moral development. There is evidence that the moral reasoning described in stage theories is not sufficient to account for moral behavior. For example, other factors such as modeling (as described by the social cognitive theory of morality) are required to explain bullying.

Rudolf Steiner's model of child development interrelates physical, emotional, cognitive, and moral development in developmental stages similar to those later described by Piaget.

Developmental theories are sometimes presented not as shifts between qualitatively different stages, but as gradual increments on separate dimensions. Development of epistemological beliefs (beliefs about knowledge) have been described in terms of gradual changes in people's belief in: certainty and permanence of knowledge, fixedness of ability, and credibility of authorities such as teachers and experts. People develop more sophisticated beliefs about knowledge as they gain in education and maturity.

Motivation

Motivation is an internal state that activates, guides and sustains behavior. Motivation can have several impacting effects on how students learn and how they behave towards subject matter:

- Provide direction towards goals

- Enhance cognitive processing abilities and performance

- Direct behavior toward particular goals

- Lead to increased effort and energy

- Increase initiation of and persistence in activities

Educational psychology research on motivation is concerned with the volition or will that students bring to a task, their level of interest and intrinsic motivation, the personally held goals that guide their behavior, and their belief about the causes of their success or failure. As intrinsic motivation deals with activities that act as their own rewards, extrinsic motivation deals with motivations that are brought on by consequences or punishments. A form of attribution theory developed by Bernard Weiner describes how students' beliefs about the causes of academic success or failure affect their emotions and motivations. For example, when students attribute failure to lack of ability, and ability is perceived as uncontrollable, they experience the emotions of shame and embarrassment and consequently decrease effort and show poorer performance. In contrast, when students attribute failure to lack of effort, and effort is perceived as controllable, they experience the emotion of guilt and consequently increase effort and show improved performance.

The self-determination theory (SDT) was developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan. SDT focuses on the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in driving human behavior and posits inherent growth and development tendencies. It emphasizes the degree to which an individual's behavior is self-motivated and self-determined. When applied to the realm of education, the self-determination theory is concerned primarily with promoting in students an interest in learning, a value of education, and a confidence in their own capacities and attributes.

Motivational theories also explain how learners' goals affect the way they engage with academic tasks. Those who have mastery goals strive to increase their ability and knowledge. Those who have performance approach goals strive for high grades and seek opportunities to demonstrate their abilities. Those who have performance avoidance goals are driven by fear of failure and avoid situations where their abilities are exposed. Research has found that mastery goals are associated with many positive outcomes such as persistence in the face of failure, preference for challenging tasks, creativity, and intrinsic motivation. Performance avoidance goals are associated with negative outcomes such as poor concentration while studying, disorganized studying, less self-regulation, shallow information processing, and test anxiety. Performance approach goals are associated with positive outcomes, and some negative outcomes such as an unwillingness to seek help and shallow information processing.

Locus of control is a salient factor in the successful academic performance of students. During the 1970s and '80s, Cassandra B. Whyte did significant educational research studying locus of control as related to the academic achievement of students pursuing higher education coursework. Much of her educational research and publications focused upon the theories of Julian B. Rotter in regard to the importance of internal control and successful academic performance. Whyte reported that individuals who perceive and believe that their hard work may lead to more successful academic outcomes, instead of depending on luck or fate, persist and achieve academically at a higher level. Therefore, it is important to provide education and counseling in this regard.

Technology

Instructional design, the systematic design of materials, activities, and interactive environments for learning, is broadly informed by educational psychology theories and research. For example, in defining learning goals or objectives, instructional designers often use a taxonomy of educational objectives created by Benjamin Bloom and colleagues. Bloom also researched mastery learning, an instructional strategy in which learners only advance to a new learning objective after they have mastered its prerequisite objectives. Bloom discovered that a combination of mastery learning with one-to-one tutoring is highly effective, producing learning outcomes far exceeding those normally achieved in classroom instruction. Gagné, another psychologist, had earlier developed an influential method of task analysis in which a terminal learning goal is expanded into a hierarchy of learning objectives connected by prerequisite relationships. The following list of technological resources incorporate computer-aided instruction and intelligence for educational psychologists and their students:

- Intelligent tutoring system

- Cognitive tutor

- Cooperative learning

- Collaborative learning

- Problem-based learning

- Computer-supported collaborative learning

- Constructive alignment

Technology is essential to the field of educational psychology, not only for the psychologist themselves as far as testing, organization, and resources, but also for students. Educational Psychologists who reside in the K-12 setting focus the majority of their time on Special Education students. It has been found that students with disabilities learning through technology such as iPad applications and videos are more engaged and motivated to learn in the classroom setting. Liu et al. explain that learning-based technology allows for students to be more focused, and learning is more efficient with learning technologies. The authors explain that learning technology also allows for students with social-emotional disabilities to participate in distance learning.

Applications

Teaching

Research on classroom management and pedagogy is conducted to guide teaching practice and form a foundation for teacher education programs. The goals of classroom management are to create an environment conducive to learning and to develop students' self-management skills. More specifically, classroom management strives to create positive teacher-student and peer relationships, manage student groups to sustain on-task behavior, and use counseling and other psychological methods to aid students who present persistent psycho-social problems.

Introductory educational psychology is a commonly required area of study in most North American teacher education programs. When taught in that context, its content varies, but it typically emphasizes learning theories (especially cognitively oriented ones), issues about motivation, assessment of students' learning, and classroom management. A developing Wikibook about educational psychology gives more detail about the educational psychology topics that are typically presented in preservice teacher education.

Counseling

Training

In order to become an educational psychologist, students can complete an undergraduate degree in their choice. They then must go to graduate school to study education psychology, counseling psychology, and/ or school counseling. Most students today are also receiving their doctorate degrees in order to hold the "psychologist" title. Educational psychologists work in a variety of settings. Some work in university settings where they carry out research on the cognitive and social processes of human development, learning and education. Educational psychologists may also work as consultants in designing and creating educational materials, classroom programs and online courses. Educational psychologists who work in k–12 school settings (closely related are school psychologists in the US and Canada) are trained at the master's and doctoral levels. In addition to conducting assessments, school psychologists provide services such as academic and behavioral intervention, counseling, teacher consultation, and crisis intervention. However, school psychologists are generally more individual-oriented towards students.

Many high schools and colleges are increasingly offering educational psychology courses, with some colleges offering it as a general education requirement. Similarly, colleges offer students opportunities to obtain a PhD. in Educational Psychology.

Within the UK, students must hold a degree that is accredited by the British Psychological Society (either undergraduate or at Masters level) before applying for a three-year doctoral course that involves further education, placement, and a research thesis.

In recent years, many university training programs in the US have included curriculum that focuses on issues of race, gender, disability, trauma, and poverty, and how those issues affect learning and academic outcomes. A growing number of universities offer specialized certificates that allow professionals to work and study in these fields (i.e. autism specialists, trauma specialists).

Employment outlook

Anticipated to grow by 18–26%, employment for psychologists in the United States is expected to grow faster than most occupations in 2014. One in four psychologists is employed in educational settings. In the United States, the median salary for psychologists in primary and secondary schools is US$58,360 as of May 2004.

In recent decades, the participation of women as professional researchers in North American educational psychology has risen dramatically.

Methods of research

Educational psychology, as much as any other field of psychology heavily relies on a balance of pure observation and quantitative methods in psychology. The study of education generally combines the studies of history, sociology, and ethics with theoretical approaches. Smeyers and Depaepe explain that historically, the study of education and child-rearing have been associated with the interests of policymakers and practitioners within the educational field, however, the recent shift to sociology and psychology has opened the door for new findings in education as a social science. Now being its own academic discipline, educational psychology has proven to be helpful for social science researchers.

Quantitative research is the backing to most observable phenomena in psychology. This involves observing, creating, and understanding distribution of data based upon the study's subject matter. Researchers use particular variables to interpret their data distributions from their research and employ statistics as a way of creating data tables and analyzing their data. Psychology has moved from the "common sense" reputations initially posed by Thomas Reid to the methodology approach comparing independent and dependent variables through natural observation, experiments, or combinations of the two. Though results are still, with statistical methods, objectively true based upon significance variables or p- values.