The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Bretons, Flemish, and men from other French provinces, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqueror.

William's claim to the English throne derived from his familial relationship with the childless Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor, who may have encouraged William's hopes for the throne. Edward died in January 1066 and was succeeded by his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson. The Norwegian king Harald Hardrada invaded northern England in September 1066 and was victorious at the Battle of Fulford on 20 September, but Godwinson's army defeated and killed Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September. Three days later on 28 September, William's invasion force of thousands of men and hundreds of ships landed at Pevensey in Sussex in southern England. Harold marched south to oppose him, leaving a significant portion of his army in the north. Harold's army confronted William's invaders on 14 October at the Battle of Hastings. William's force defeated Harold, who was killed in the engagement, and William became king.

Although William's main rivals were gone, he still faced rebellions over the following years and was not secure on the English throne until after 1072. The lands of the resisting English elite were confiscated; some of the elite fled into exile. To control his new kingdom, William granted lands to his followers and built castles commanding military strongpoints throughout the land. The Domesday Book, a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales, was completed by 1086. Other effects of the conquest included the court and government, the introduction of the Norman language as the language of the elites, and changes in the composition of the upper classes, as William enfeoffed lands to be held directly from the king. More gradual changes affected the agricultural classes and village life: the main change appears to have been the formal elimination of slavery, which may or may not have been linked to the invasion. There was little alteration in the structure of government, as the new Norman administrators took over many of the forms of Anglo-Saxon government.

Origins

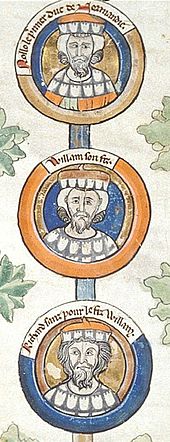

In 911, the Carolingian French ruler Charles the Simple allowed a group of Vikings under their leader Rollo to settle in Normandy as part of the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte. In exchange for the land, the Norsemen under Rollo were expected to provide protection along the coast against further Viking invaders. Their settlement proved successful, and the Vikings in the region became known as the "Northmen" from which "Normandy" and "Normans" are derived. The Normans quickly adopted the indigenous culture as they became assimilated by the French, renouncing paganism and converting to Christianity. They adopted the langue d'oïl of their new home and added features from their own Norse language, transforming it into the Norman language. They intermarried with the local population and used the territory granted to them as a base to extend the frontiers of the duchy westward, annexing territory including the Bessin, the Cotentin Peninsula and Avranches.

In 1002, English king Æthelred the Unready married Emma of Normandy, the sister of Richard II, Duke of Normandy. Their son Edward the Confessor, who spent many years in exile in Normandy, succeeded to the English throne in 1042. This led to the establishment of a powerful Norman interest in English politics, as Edward drew heavily on his former hosts for support, bringing in Norman courtiers, soldiers, and clerics and appointing them to positions of power, particularly in the Church. Childless and embroiled in conflict with the formidable Godwin, Earl of Wessex and his sons, Edward may also have encouraged Duke William of Normandy's ambitions for the English throne.

When King Edward died at the beginning of 1066, the lack of a clear heir led to a disputed succession in which several contenders laid claim to the throne of England. Edward's immediate successor was the Earl of Wessex, Harold Godwinson, the richest and most powerful of the English aristocrats. Harold was elected king by the Witenagemot of England and crowned by the Archbishop of York, Ealdred, although Norman propaganda claimed the ceremony was performed by Stigand, the uncanonically elected Archbishop of Canterbury. Harold was immediately challenged by two powerful neighbouring rulers. Duke William claimed that he had been promised the throne by King Edward and that Harold had sworn agreement to this; King Harald III of Norway, commonly known as Harald Hardrada, also contested the succession. His claim to the throne was based on an agreement between his predecessor, Magnus the Good, and the earlier English king, Harthacnut, whereby if either died without heir, the other would inherit both England and Norway. William and Harald at once set about assembling troops and ships to invade England.

Tostig's raids and the Norwegian invasion

In early 1066, Harold's exiled brother, Tostig Godwinson, raided southeastern England with a fleet he had recruited in Flanders, later joined by other ships from Orkney. Threatened by Harold's fleet, Tostig moved north and raided in East Anglia and Lincolnshire, but he was driven back to his ships by the brothers Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and Morcar, Earl of Northumbria. Deserted by most of his followers, Tostig withdrew to Scotland, where he spent the summer recruiting fresh forces. King Harold spent the summer on the south coast with a large army and fleet waiting for William to invade, but the bulk of his forces were militia who needed to harvest their crops, so on 8 September Harold dismissed them.

Hardrada invaded northern England in early September, leading a fleet of more than 300 ships carrying perhaps 15,000 men. Harald's army was further augmented by the forces of Tostig, who threw his support behind the Norwegian king's bid for the throne. Advancing on York, the Norwegians defeated a northern English army under Edwin and Morcar on 20 September at the Battle of Fulford. The two earls had rushed to engage the Norwegian forces before Harold could arrive from the south. Although Harold Godwinson had married Edwin and Morcar's sister Ealdgyth, the two earls may have distrusted Harold and feared that the king would replace Morcar with Tostig. The end result was that their forces were devastated and unable to participate in the rest of the campaigns of 1066, although the two earls survived the battle.

Hardrada moved on to York, which surrendered to him. After taking hostages from the leading men of the city, on 24 September the Norwegians moved east to the tiny village of Stamford Bridge. King Harold probably learned of the Norwegian invasion in mid-September and rushed north, gathering forces as he went. The royal forces probably took nine days to cover the distance from London to York, averaging almost 25 miles (40 kilometres) per day. At dawn on 25 September Harold's forces reached York, where he learned the location of the Norwegians. The English then marched on the invaders and took them by surprise, defeating them in the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Harald of Norway and Tostig were killed, and the Norwegians suffered such horrific losses that only 24 of the original 300 ships were required to carry away the survivors. The English victory was costly, however, as Harold's army was left in a battered and weakened state, and far from the English Channel.

Norman invasion

Norman preparations and forces

William assembled a large invasion fleet and an army gathered from Normandy and all over France, including large contingents from Brittany and Flanders. He mustered his forces at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme and was ready to cross the Channel by about 12 August. The exact numbers and composition of William's force are unknown. A contemporary document claims that William had 726 ships, but this may be an inflated figure. Figures given by contemporary writers are highly exaggerated, varying from 14,000 to 150,000 men. Modern historians have offered a range of estimates for the size of William's forces: 7000–8000 men, 1000–2000 of them cavalry; 10,000–12,000 men; 10,000 men, 3000 of them cavalry; or 7500 men. The army would have consisted of a mix of cavalry, infantry, and archers or crossbowmen, with about equal numbers of cavalry and archers and the foot soldiers equal in number to the other two types combined. Although later lists of companions of William the Conqueror are extant, most are padded with extra names; only about 35 individuals can be reliably claimed to have been with William at Hastings.

William of Poitiers states that William obtained Pope Alexander II's consent for the invasion, signified by a papal banner, along with diplomatic support from other European rulers. Although Alexander did give papal approval to the conquest after it succeeded, no other source claims papal support before the invasion. William's army assembled during the summer while an invasion fleet in Normandy was constructed. Although the army and fleet were ready by early August, adverse winds kept the ships in Normandy until late September. There were probably other reasons for William's delay, including intelligence reports from England revealing that Harold's forces were deployed along the coast. William would have preferred to delay the invasion until he could make an unopposed landing.

Landing and Harold's march south

The Normans crossed to England a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge on 25 September, following the dispersal of Harold's naval force. They landed at Pevensey in Sussex on 28 September and erected a wooden castle at Hastings, from which they raided the surrounding area. This ensured supplies for the army, and as Harold and his family held many of the lands in the area, it weakened William's opponent and made him more likely to attack to put an end to the raiding.

Harold, after defeating his brother Tostig and Harald Hardrada in the north, left much of his force there, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest of his army south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion. It is unclear when Harold learned of William's landing, but it was probably while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London for about a week before reaching Hastings, so it is likely that he took a second week to march south, averaging about 27 miles (43 kilometres) per day, for the nearly 200 miles (320 kilometres) to London. Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle remain obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy. Harold had taken up a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 miles (10 kilometres) from William's castle at Hastings.

Contemporary sources do not give reliable data on the size and composition of Harold's army, although two Norman sources give figures of 1.2 million or 400,000 men. Recent historians have suggested figures of between 5000 and 13,000 for Harold's army at Hastings, but most agree on a range of between 7000 and 8000 English troops. These men would have comprised a mix of the fyrd (militia mainly composed of foot soldiers) and the housecarls, or nobleman's personal troops, who usually also fought on foot. The main difference between the two types was in their armour; the housecarls used better protecting armour than that of the fyrd. The English army does not appear to have had many archers, although some were present. The identities of few of the Englishmen at Hastings are known; the most important were Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine. About 18 other named individuals can reasonably be assumed to have fought with Harold at Hastings, including two other relatives.

Hastings

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October 1066 and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources. Although the numbers on each side were probably about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few archers. The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall along the ridge, and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton troops panicked and fled, and some of the English troops appear to have pursued the fleeing Bretons. Norman cavalry then attacked and killed the pursuing troops. While the Bretons were fleeing, rumours swept the Norman forces that the duke had been killed, but William rallied his troops. Twice more the Normans made feigned withdrawals, tempting the English into pursuit, and allowing the Norman cavalry to attack them repeatedly. The available sources are more confused about events in the afternoon, but it appears that the decisive event was the death of Harold, about which different stories are told. William of Jumieges claimed that Harold was killed by the duke. The Bayeux Tapestry has been claimed to show Harold's death by an arrow to the eye, but this may be a later reworking of the tapestry to conform to 12th-century stories that Harold had died from an arrow wound to the head. Other sources stated that no one knew how Harold died because the press of battle was so tight around the king that the soldiers could not see who struck the fatal blow. William of Poitiers gives no details at all about Harold's death.

Aftermath of Hastings

The day after the battle, Harold's body was identified, either by his armour or marks on his body. The bodies of the English dead, who included some of Harold's brothers and his housecarls, were left on the battlefield, although some were removed by relatives later. Gytha, Harold's mother, offered the victorious duke the weight of her son's body in gold for its custody, but her offer was refused. William ordered that Harold's body be thrown into the sea, but whether that took place is unclear. Another story relates that Harold was buried at the top of a cliff. Waltham Abbey, which had been founded by Harold, later claimed that his body had been buried there secretly. Later legends claimed that Harold did not die at Hastings, but escaped and became a hermit at Chester.

After his victory at Hastings, William expected to receive the submission of the surviving English leaders, but instead Edgar the Ætheling was proclaimed king by the Witenagemot, with the support of Earls Edwin and Morcar, Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Ealdred, the Archbishop of York. William therefore advanced, marching around the coast of Kent to London. He defeated an English force that attacked him at Southwark, but being unable to storm London Bridge he sought to reach the capital by a more circuitous route.

William moved up the Thames valley to cross the river at Wallingford, Berkshire; while there he received the submission of Stigand. He then travelled north-east along the Chilterns, before advancing towards London from the north-west, fighting further engagements against forces from the city. Having failed to muster an effective military response, Edgar's leading supporters lost their nerve, and the English leaders surrendered to William at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. William was acclaimed King of England and crowned by Ealdred on 25 December 1066, in Westminster Abbey. The new king attempted to conciliate the remaining English nobility by confirming Morcar, Edwin and Waltheof, the Earl of Northumbria, in their lands as well as giving some land to Edgar the Ætheling. William remained in England until March 1067, when he returned to Normandy with English prisoners, including Stigand, Morcar, Edwin, Edgar the Ætheling, and Waltheof.

English resistance

First rebellions

Despite the submission of the English nobles, resistance continued for several years. William left control of England in the hands of his half-brother Odo and one of his closest supporters, William fitzOsbern. In 1067 rebels in Kent launched an unsuccessful attack on Dover Castle in combination with Eustace II of Boulogne. The Shropshire landowner Eadric the Wild, in alliance with the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd and Powys, raised a revolt in western Mercia, fighting Norman forces based in Hereford. These events forced William to return to England at the end of 1067. In 1068 William besieged rebels in Exeter, including Harold's mother Gytha, and after suffering heavy losses managed to negotiate the town's surrender. In May, William's wife Matilda was crowned queen at Westminster, an important symbol of William's growing international stature. Later in the year Edwin and Morcar raised a revolt in Mercia with Welsh assistance, while Gospatric, the newly appointed Earl of Northumbria, led a rising in Northumbria, which had not yet been occupied by the Normans. These rebellions rapidly collapsed as William moved against them, building castles and installing garrisons as he had already done in the south. Edwin and Morcar again submitted, while Gospatric fled to Scotland, as did Edgar the Ætheling and his family, who may have been involved in these revolts. Meanwhile, Harold's sons, who had taken refuge in Ireland, raided Somerset, Devon and Cornwall from the sea.

Revolts of 1069

Early in 1069 the newly installed Norman Earl of Northumbria, Robert de Comines, and several hundred soldiers accompanying him were massacred at Durham; the Northumbrian rebellion was joined by Edgar, Gospatric, Siward Barn and other rebels who had taken refuge in Scotland. The castellan of York, Robert fitzRichard, was defeated and killed, and the rebels besieged the Norman castle at York. William hurried north with an army, defeated the rebels outside York and pursued them into the city, massacring the inhabitants and bringing the revolt to an end. He built a second castle at York, strengthened Norman forces in Northumbria and then returned south. A subsequent local uprising was crushed by the garrison of York. Harold's sons launched a second raid from Ireland and were defeated at the Battle of Northam in Devon by Norman forces under Count Brian, a son of Eudes, Count of Penthièvre. In August or September 1069 a large fleet sent by Sweyn II of Denmark arrived off the coast of England, sparking a new wave of rebellions across the country. After abortive raids in the south, the Danes joined forces with a new Northumbrian uprising, which was also joined by Edgar, Gospatric and the other exiles from Scotland as well as Waltheof. The combined Danish and English forces defeated the Norman garrison at York, seized the castles and took control of Northumbria, although a raid into Lincolnshire led by Edgar was defeated by the Norman garrison of Lincoln.

At the same time resistance flared up again in western Mercia, where the forces of Eadric the Wild, together with his Welsh allies and further rebel forces from Cheshire and Shropshire, attacked the castle at Shrewsbury. In the south-west, rebels from Devon and Cornwall attacked the Norman garrison at Exeter but were repulsed by the defenders and scattered by a Norman relief force under Count Brian. Other rebels from Dorset, Somerset and neighbouring areas besieged Montacute Castle but were defeated by a Norman army gathered from London, Winchester and Salisbury under Geoffrey of Coutances. Meanwhile, William attacked the Danes, who had moored for the winter south of the Humber in Lincolnshire, and drove them back to the north bank. Leaving Robert of Mortain in charge of Lincolnshire, he turned west and defeated the Mercian rebels in battle at Stafford. When the Danes attempted to return to Lincolnshire, the Norman forces there again drove them back across the Humber. William advanced into Northumbria, defeating an attempt to block his crossing of the swollen River Aire at Pontefract. The Danes fled at his approach, and he occupied York. He bought off the Danes, who agreed to leave England in the spring, and during the winter of 1069–70 his forces systematically devastated Northumbria in the Harrying of the North, subduing all resistance. As a symbol of his renewed authority over the north, William ceremonially wore his crown at York on Christmas Day 1069.

In early 1070, having secured the submission of Waltheof and Gospatric, and driven Edgar and his remaining supporters back to Scotland, William returned to Mercia, where he based himself at Chester and crushed all remaining resistance in the area before returning to the south. Papal legates arrived and at Easter re-crowned William, which would have symbolically reasserted his right to the kingdom. William also oversaw a purge of prelates from the Church, most notably Stigand, who was deposed from Canterbury. The papal legates also imposed penances on William and those of his supporters who had taken part in Hastings and the subsequent campaigns. As well as Canterbury, the see of York had become vacant following the death of Ealdred in September 1069. Both sees were filled by men loyal to William: Lanfranc, abbot of William's foundation at Caen, received Canterbury while Thomas of Bayeux, one of William's chaplains, was installed at York. Some other bishoprics and abbeys also received new bishops and abbots and William confiscated some of the wealth of the English monasteries, which had served as repositories for the assets of the native nobles.

Danish troubles

In 1070 Sweyn II of Denmark arrived to take personal command of his fleet and renounced the earlier agreement to withdraw, sending troops into the Fens to join forces with English rebels led by Hereward the Wake, at that time based on the Isle of Ely. Sweyn soon accepted a further payment of Danegeld from William, and returned home. After the departure of the Danes the Fenland rebels remained at large, protected by the marshes, and early in 1071 there was a final outbreak of rebel activity in the area. Edwin and Morcar again turned against William, and although Edwin was quickly betrayed and killed, Morcar reached Ely, where he and Hereward were joined by exiled rebels who had sailed from Scotland. William arrived with an army and a fleet to finish off this last pocket of resistance. After some costly failures the Normans managed to construct a pontoon to reach the Isle of Ely, defeated the rebels at the bridgehead and stormed the island, marking the effective end of English resistance. Morcar was imprisoned for the rest of his life; Hereward was pardoned and had his lands returned to him.

Last resistance

William faced difficulties in his continental possessions in 1071, but in 1072 he returned to England and marched north to confront King Malcolm III of Scotland. This campaign, which included a land army supported by a fleet, resulted in the Treaty of Abernethy in which Malcolm expelled Edgar the Ætheling from Scotland and agreed to some degree of subordination to William. The exact status of this subordination was unclear – the treaty merely stated that Malcolm became William's man. Whether this meant only for Cumbria and Lothian or for the whole Scottish kingdom was left ambiguous.

In 1075, during William's absence, Ralph de Gael, the Earl of Norfolk, and Roger de Breteuil the Earl of Hereford, conspired to overthrow him in the Revolt of the Earls. The exact reason for the rebellion is unclear, but it was launched at the wedding of Ralph to a relative of Roger's, held at Exning. Another earl, Waltheof, despite being one of William's favourites, was also involved, and some Breton lords were ready to offer support. Ralph also requested Danish aid. William remained in Normandy while his men in England subdued the revolt. Roger was unable to leave his stronghold in Herefordshire because of efforts by Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester, and Æthelwig, the Abbot of Evesham. Ralph was bottled up in Norwich Castle by the combined efforts of Odo of Bayeux, Geoffrey of Coutances, Richard fitzGilbert, and William de Warenne. Norwich was besieged and surrendered, and Ralph went into exile. Meanwhile, the Danish king's brother, Cnut, had finally arrived in England with a fleet of 200 ships, but he was too late as Norwich had already surrendered. The Danes then raided along the coast before returning home. William did not return to England until later in 1075, to deal with the Danish threat and the aftermath of the rebellion, celebrating Christmas at Winchester. Roger and Waltheof were kept in prison, where Waltheof was executed in May 1076. By that time William had returned to the continent, where Ralph was continuing the rebellion from Brittany.

Control of England

Once England had been conquered, the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control. They were few in number compared to the native English population; including those from other parts of France, historians estimate the number of Norman landholders at around 8000. William's followers expected and received lands and titles in return for their service in the invasion, but William claimed ultimate possession of the land in England over which his armies had given him de facto control, and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Henceforth, all land was "held" directly from the king in feudal tenure in return for military service. A Norman lord typically had properties scattered piecemeal throughout England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block.

To find the lands to compensate his Norman followers, William initially confiscated the estates of all the English lords who had fought and died with Harold and redistributed part of their lands. These confiscations led to revolts, which resulted in more confiscations, a cycle that continued for five years after the Battle of Hastings. To put down and prevent further rebellions the Normans constructed castles and fortifications in unprecedented numbers, initially mostly on the motte-and-bailey pattern. Historian Robert Liddiard remarks that "to glance at the urban landscape of Norwich, Durham or Lincoln is to be forcibly reminded of the impact of the Norman invasion". William and his barons also exercised tighter control over inheritance of property by widows and daughters, often forcing marriages to Normans.

A measure of William's success in taking control is that, from 1072 until the Capetian conquest of Normandy in 1204, William and his successors were largely absentee rulers. For example, after 1072, William spent more than 75 per cent of his time in France rather than England. While he needed to be personally present in Normandy to defend the realm from foreign invasion and put down internal revolts, he set up royal administrative structures that enabled him to rule England from a distance.

Consequences

Elite replacement

A direct consequence of the invasion was the almost total elimination of the old English aristocracy and the loss of English control over the Catholic Church in England. William systematically dispossessed English landowners and conferred their property on his continental followers. The Domesday Book meticulously documents the impact of this colossal programme of expropriation, revealing that by 1086 only about 5 percent of land in England south of the Tees was left in English hands. Even this tiny residue was further diminished in the decades that followed, the elimination of native landholding being most complete in southern parts of the country.

Natives were also removed from high governmental and ecclesiastical office. After 1075 all earldoms were held by Normans, and Englishmen were only occasionally appointed as sheriffs. Likewise in the Church, senior English office-holders were either expelled from their positions or kept in place for their lifetimes and replaced by foreigners when they died. By 1096 no bishopric was held by any Englishman, and English abbots became uncommon, especially in the larger monasteries.

English emigration

Following the conquest, many Anglo-Saxons, including groups of nobles, fled the country for Scotland, Ireland, or Scandinavia. Members of King Harold Godwinson's family sought refuge in Ireland and used their bases in that country for unsuccessful invasions of England. The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the Byzantine Empire. The empire became a popular destination for many English nobles and soldiers, as the Byzantines were in need of mercenaries. The English became the predominant element in the elite Varangian Guard, until then a largely Scandinavian unit, from which the emperor's bodyguard was drawn. Some of the English migrants were settled in Byzantine frontier regions on the Black Sea coast and established towns with names such as New London and New York.

Governmental systems

Before the Normans arrived, Anglo-Saxon governmental systems were more sophisticated than their counterparts in Normandy. All of England was divided into administrative units called shires, with subdivisions; the royal court was the centre of government, and a justice system based on local and regional tribunals existed to secure the rights of free men. Shires were run by officials known as shire reeves or sheriffs. Most medieval governments were always on the move, holding court wherever the weather and food or other matters were best at the moment; England had a permanent treasury at Winchester before William's conquest. One major reason for the strength of the English monarchy was the wealth of the kingdom, built on the English system of taxation that included a land tax, or the geld. English coinage was also superior to most of the other currency in use in northwestern Europe, and the ability to mint coins was a royal monopoly. The English kings had also developed the system of issuing writs to their officials, in addition to the normal medieval practice of issuing charters. Writs were either instructions to an official or group of officials, or notifications of royal actions such as appointments to office or a grant of some sort.

This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and was the foundation of further developments. They kept the framework of government but made changes in the personnel, although at first the new king attempted to keep some natives in office. By the end of William's reign most of the officials of government and the royal household were Normans. The language of official documents also changed, from Old English to Latin. The forest laws were introduced, leading to the setting aside of large sections of England as royal forest. The Domesday survey was an administrative catalogue of the landholdings of the kingdom, and was unique to medieval Europe. It was divided into sections based on the shires, and listed all the landholdings of each tenant-in-chief of the king as well as who had held the land before the conquest.

Language

One of the most obvious effects of the conquest was the introduction of Anglo-Norman, a northern dialect of Old French with limited Nordic influences, as the language of the ruling classes in England, displacing Old English. Norman French words entered the English language, and a further sign of the shift was the usage of names common in France instead of Anglo-Saxon names. Male names such as William, Robert, and Richard soon became common; female names changed more slowly. The Norman invasion had little impact on placenames, which had changed significantly after earlier Scandinavian invasions. It is not known precisely how much English the Norman invaders learned, nor how much the knowledge of Norman French spread among the lower classes, but the demands of trade and basic communication probably meant that at least some of the Normans and native English were bilingual. Nevertheless, William the Conqueror never developed a working knowledge of English and for centuries afterwards English was not well understood by the nobility.

Immigration and intermarriage

An estimated 8000 Normans and other continentals settled in England as a result of the conquest, although exact figures cannot be established. Some of these new residents intermarried with the native English, but the extent of this practice in the years immediately after Hastings is unclear. Several marriages are attested between Norman men and English women during the years before 1100, but such marriages were uncommon. Most Normans continued to contract marriages with other Normans or other continental families rather than with the English. Within a century of the invasion, intermarriage between the native English and the Norman immigrants had become common. By the early 1160s, Ailred of Rievaulx was writing that intermarriage was common in all levels of society.

Society

The impact of the conquest on the lower levels of English society is difficult to assess. The major change was the elimination of slavery in England, which had disappeared by the middle of the 12th century. There were about 28,000 slaves listed in Domesday Book in 1086, fewer than had been enumerated for 1066. In some places, such as Essex, the decline in slaves was 20 per cent for the 20 years. The main reasons for the decline in slaveholding appear to have been the disapproval of the Church and the cost of supporting slaves, who unlike serfs, had to be maintained entirely by their owners. The practice of slavery was not outlawed, and the Leges Henrici Primi from the reign of King Henry I continue to mention slaveholding as legal.

Many of the free peasants of Anglo-Saxon society appear to have lost status and become indistinguishable from the non-free serfs. Whether this change was due entirely to the conquest is unclear, but the invasion and its after-effects probably accelerated a process already under way. The spread of towns and increase in nucleated settlements in the countryside, rather than scattered farms, was probably accelerated by the coming of the Normans to England. The lifestyle of the peasantry probably did not greatly change in the decades after 1066. Although earlier historians argued that women became less free and lost rights with the conquest, current scholarship has mostly rejected this view. Little is known about women other than those in the landholding class, so no conclusions can be drawn about peasant women's status after 1066. Noblewomen appear to have continued to influence political life mainly through their kinship relationships. Both before and after 1066 aristocratic women could own land, and some women continued to have the ability to dispose of their property as they wished.

Historiography

Debate over the conquest started almost immediately. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, when discussing the death of William the Conqueror, denounced him and the conquest in verse, but the king's obituary notice from William of Poitiers, a Frenchman, was full of praise. Historians since then have argued over the facts of the matter and how to interpret them, with little agreement. The theory or myth of the "Norman yoke" arose in the 17th century, the idea that Anglo-Saxon society had been freer and more equal than the society that emerged after the conquest. This theory owes more to the period in which it was developed than to historical facts, but it continues to be used to the present day in both political and popular thought.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, historians have focused less on the rightness or wrongness of the conquest itself, instead concentrating on the effects of the invasion. Some, such as Richard Southern, have seen the conquest as a critical turning point in history. Southern stated that "no country in Europe, between the rise of the barbarian kingdoms and the 20th century, has undergone so radical a change in so short a time as England experienced after 1066". Other historians, such as H. G. Richardson and G. O. Sayles, believe that the transformation was less radical. In more general terms, Singman has called the conquest "the last echo of the national migrations that characterized the early Middle Ages". The debate over the impact of the conquest depends on how change after 1066 is measured. If Anglo-Saxon England was already evolving before the invasion, with the introduction of feudalism, castles or other changes in society, then the conquest, while important, did not represent radical reform. But the change was dramatic if measured by the elimination of the English nobility or the loss of Old English as a literary language. Nationalistic arguments have been made on both sides of the debate, with the Normans cast as either the persecutors of the English or the rescuers of the country from a decadent Anglo-Saxon nobility.