Digital rhetoric can be generally defined as communication that exists in the digital sphere. As such, digital rhetoric can be expressed in many different forms —including but not limited to text, images, videos, and software. Due to the increasingly mediated nature of our contemporary society, there are no longer clear distinctions between digital and non-digital environments. This has led to an expansion of the scope of digital rhetoric as there is a need to account for the increased fluidity with which humans interact with technology.

Evolving definitions suggest that digital rhetoric has held various meanings to different scholars over time. Similarly, digital rhetoric can take on a variety of meanings based on what is being analyzed—which depends on the concept, forms or objects of study, or rhetorical approach. Digital rhetoric can also be analyzed through many lenses that reflect different social movements. Approaching this area of study through different the lens of varying social issues allows the reach of digital rhetoric to expand far beyond the individualistic encounters one has with technology.

Definition

Evolving definition of 'digital rhetoric'

The following subsections detail the evolving definition 'digital rhetoric' as a term since its creation in 1989.

Early definitions (1989 - 2015)

The term digital rhetoric was coined by rhetorician Richard A. Lanham in a lecture he delivered in 1989 and first formally put into words in his 1993 essay collection, The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts.

Recent scholarship (2015 - Present)

Drawing influence from Lanham and Losh, Douglas Eyman offered his own definition of digital rhetoric in his 2015 book Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. Eyman said digital rhetoric is "the application of rhetorical theory (as analytic method or heuristic for production) to digital texts and performances".

Eyman's definition demonstrates that digital rhetoric can be applied as an analytic method for digital texts and as a heuristic for production offering rhetorical questions that a composer can use to create digital texts. Eyman categorized the emerging field of digital rhetoric as interdisciplinary in nature, enriched by related fields such as, but not limited to: digital literacy, visual rhetoric, new media, human-computer interaction and critical code studies.

In 2018, rhetorician Angela Haas offered her own definition of digital rhetoric, defining it as "the digital negotiation of information – and its historical, social, economic, and political contexts and influences – to affect change". Haas emphasized that digital rhetoric does not solely apply to text-based items—it can also apply to image-based or system-based items. In other words, any form of communication that occurs in the digital sphere can be counted as digital rhetoric under Haas' definition.

Other definitions

Contrary to past conceptions, the definition of rhetoric can no longer be confined to simply the sending and receiving of messages to persuade or impart knowledge. While this represents a primarily ancient Western view of rhetoric, Arthur Smith of UCLA explains that the ancient rhetoric of many cultures, such as African rhetoric, existed independent of Western influence. Today, rhetoric encompasses all forms of discourse that serve any given purpose within specific contexts, while also simultaneously being shaped by those contexts.

Some scholars interpret this rhetorical discourse with greater focus on the digital aspect. Casey Boyle, James Brown Jr., and Steph Ceraso claim that "the digital" is no longer just one of the many different tools that can be used to enhance traditional rhetoric, but an "ambient condition" that encompasses our everyday lives. In other words, as technology becomes more and more ubiquitous, the lines between traditional and digital rhetoric will start to blur. In addition, Boyle et al. emphasize the idea that both technology and rhetoric can influence and transform each other.

Concepts

Circulation

Circulation theorizes the ways that text and discourse moves through time and space, and any kind of media can be circulated. A new form of communication is composed, created, and distributed through digital technologies. Media scholar Henry Jenkins explains there is a shift from distribution to circulation, which signals a move toward an increasingly participatory model of culture in which people shape, share, re-frame and remix media content in ways not previously possible within the traditional rhetorical formats like print. The various concepts of circulation include:

- Collaboration – Digital rhetoric has taken on a very collaborative nature through the use of digital platforms. Sites such as YouTube and Wikipedia involve opportunity for "new forms of collaborative production". Digital platforms have created opportunities for more people to enact and create, as digital platforms open doors for collaborative communication that can occur synchronously, asynchronously, over far distances, and across multiple disciplines and professions.

- Crowdsourcing – Daren Brabham describes the concept of crowdsourcing as the use of modern technology to collaborate, create, and solve problems collectively. However, ethical concerns have been raised as well while engaging in crowdsourcing without a clear set of compensation practices or protections in place to secure information.

- Delivery – Whereas rhetoric once relied largely on oral methods, the rise of digital technologies allows rhetoric to be delivered in new "electronic forms of discourse". Acts and modes of communication can be represented digitally by combining multiple different forms of media into a composite helping to create an easy user experience. The growing popularity of the internet meme is an example of combining, circulating, and delivering media in a collaborative effort through file sharing. Although memes are sent through microtransactions - they often can have a macro large scale impact. Another form of unique rhetorical delivery is the online encyclopedia which traditionally have been print form based primarily on text and images. However, modern technological developments now enable encyclopedias to integrate sound, animation, video, algorithmic search functions, and high-level productions into a cohesive multimedia experience as part of their new forms of digital rhetoric.

Critical literacy

Critical literacy is a line of thought that assumes all texts are biased. For example, a study conducted at the Indiana University in Bloomington used algorithms to assess 14 million Twitter messages containing statements about the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign and election. They found that from May 2016 to March 2017, social bots were responsible for causing approximately 389,000 unsupported political claims to go viral. Further, critical literacy can also be defined as a communicative tool to lead to social change and promote social action by using a critical lens when approaching social-political topics. Since so much information is thrust at a digital audience, it's important for those who are being inundated with so much information develop the tools necessary to process and critically examine the works surrounding our topics of interest - and topics unknown. In an essay on Critical Literacy in writing, the University of Melbourne states that it's important to develop these skills through reading and asking what texts are trying to accomplish, leaving it up to the reader to decide how ideas are interpreted.

Interactivity

In regards to digital rhetoric, interactivity can be defined as the ways in which readers connect to and communicate with digital texts. For example, readers have the ability to like, share, repost, comment on, and remix online content. These simple interactions allow writers, scholars, and content creators to get a better idea of how their work is affecting their audience.

Ways communicators promote interactivity consist of the following:

- Mind sharing is a way to get collective intelligence—crowd wisdom that is comparable to expert wisdom. The methodology consists of taking a consensus from the crowd—the answer that most minds are suggesting is the best answer. If it's a numeric question (like guessing the weight of an ox), it's a calculated average or median. If it's an open question (like "what car should I buy?"), it's the most common answer.

- Multimodality is a form of communication that uses multiple methods (or modes) to inform audiences of an idea. It can involve a mix of written text, pictures, audio, or videos. Online journals often embrace multimodality in their issues and articles by publishing works that use more than just written text to communicate the message. While the digital turn in rhetoric and composition has encouraged more discussion, theorization, and pedagogical application of multimodality and multimodal texts, the history of the field demonstrates a continuous concern with multimodal communication beginning with classical rhetoric's concern with delivery, gesture, and memory. All writing and all communication is, theoretically, multimodal.

- Remix is a method of digital rhetoric that manipulates and transforms an original work to convey a new message. The use of remix can help the creator make an argument by connecting seemingly unrelated ideas into a convincing whole. As modern technology develops, self-publication sites such as: YouTube, SoundCloud, and WordPress have stimulated remix culture, allowing for easier creation and dissemination of reworked content. Unlike appropriation, which is the use and potential recontextualization of existing material without significant modification, remix is defined in Kairos as "the process of taking old pieces of text, images, sounds, and video and stitching them together to form a new product". A popular example of remixing is the creation and sharing of memes.

Procedural rhetoric

Procedural rhetoric is rhetoric formed through processes or practices. Some scholars view video games as one of these processes through which rhetoric can be formed. For example, Ludology scholar and game designer Gonzalo Frasca poses that the simulation-nature of computers and video games offers a "natural medium for modeling reality and fiction". Therefore, according to Frasca, video games can take on a new form of digital rhetoric in which reality is mimicked but also created for the future. Similarly, scholar Ian Bogost argues that video games can serve as models for how 'real-world' cultural and social systems operate. They also argue for the necessity of literacy in playing video games as this allows players to challenge (and ultimately accept or reject) the rhetorical standpoints of these games.

Rhetorical velocity

Rhetorical velocity is the concept of authors writing in a way in which they are able to predict how their work might be recomposed. Digital rhetoric is often labelled using tags, for example, which are keywords that readers can type into search engines in order to help them find, view, and share relevant texts and information. These tags can be found on blog posts, news articles, scholarly journals, and more. Tagging allows writers, scholars, and content creators to organize their work and make it more accessible and understandable to readers. Therefore, it is important for them to be able to predict how their audience will recompose their works. Jim Ridolfo and Danielle DeVoss first coined this idea in 2009 when they describe rhetorical velocity as "a conscious rhetorical concern for distance, travel, speed, and time, pertaining specifically to theorizing instances of strategic appropriation by a third party".

Appropriation carries both positive and negative connotations for rhetorical velocity. In some ways, appropriation is a tool that can be used for the reapplication of outdated ideas to make them better. In other ways, appropriation is seen as a threat to creative and cultural identities. Social media receives the bulk of this scrutiny due to the lack of education of its users. Most "contributors are often unaware of what they are contributing", which perpetuates the negative connotation. Many scholars in digital rhetoric explore this topic and its effects on society such as Jessica Reyman, Amy Hea, and Johndan Johnson-Eilola.

Visual rhetoric

Digital rhetoric often invokes visual rhetoric due to digital rhetoric's reliance on visuals. Charles Hill states that images "do not necessarily have to portray an object, or even a class of objects, that exists or ever did exist" to remain impactful. However, the use of imagery for rhetorical purposes in digital spaces can't always be easily differentiated from "traditional" physical visual mediums. As such, approaching this concept requires a careful analysis of the viewer, situational, and visual contexts involved. A prominent part of this concept is its intersection of perspective with technology, as computers allow users to create a curated view for online space. Social media platforms like Instagram, incredibly realistic deepfakes, editing software like Photoshop, and even behind-the-scenes preference algorithms all illustrate how the tactile-visual internet heavily relies on and adapts principles of visual rhetoric.

Digitally-produced art is a significant way users express themselves on technological platforms; the unique intersection of text and image has given rise to new rhetorical language through the modification of slang and ingroup language. In particular, the culturally-specific and nuanced use of pop culture references through internet memes have gradually built upon themselves to create complex, highly flexible, and internet-specific (or even platform-specific) dialects of speech. Through popularity-based natural selection, edits of commonly accepted meme templates fuel the cycle of rhetorical creation.

Digital-visual rhetoric doesn't only rely on intentional manipulation. Sometimes, meanings can arise from unexpected places and otherwise-overlooked features. For example, emojis, or simple graphic images included in most texting applications, can carry heavy consequences by permeating daily communication. Varying skin tones provided (or excluded) by developers for emojis may perpetuate preexisting racial biases of colorism. Even otherwise-innocuous images of peaches and eggplants are regular stand-ins for genital regions; they can be both harmless modes of flirtation and even tools for sexually harassing women online when sent en masse.

The concept of the avatar can also aid understanding of visual rhetoric's deeply personal impact, particularly when using James E. Porter's definition of the avatar as an extended "virtual body." While scholars such as Beth Kolko hoped for an equitable online world free of physical barriers, social issues still persist in digital realms, such as gender discrimination and racism. For example, Victoria Woolums found that, in the video game World of Warcraft, an avatar's gender identity instigated bias from other characters even though an avatar's gender identity may not be physically accurate to its user. These relationships are further complicated by the varying degrees of anonymity characterizing inter-user communications in online spaces. While the possibility of true privacy can be facilitated by impersonal avatars, they are still personal manifestations of a user's self in the context of digital spaces. Furthermore, the tools available to curate and express these are platform-dependent and ripe for both liberation and exploitation. Be it 2014's Gamergate or the more recent debates regarding social media influencer culture and their portrayals of impossible and computer-edited body image, self-presentation is heavily mediated by accessibility to and mastery of online avatars.

Forms and objects of study

Infrastructure

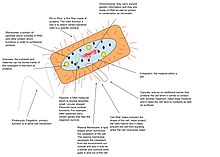

Information infrastructure is the invisible force that organizes the public's information on the internet. Essentially, information infrastructure is what impacts how and what the public accesses on the internet. Databases and search engines are information infrastructure as they play a large role in access to and dissemination of information. Information Infrastructure often consists of algorithms and metadata standards, which curate the information presented to the public.

Software

Coding and software engineering are not often recognized as rhetorical writing practices, but in the process of writing code, people instruct machines to "make arguments and judgments and address audiences both mechanic and human." Technologies themselves can be viewed as rhetorical genres, simultaneously guiding users' experiences and communication with each other and being shaped and improved through humans use. Choices baked into software that are invisible to users impact the user experience and reveal information about the priorities of the software engineers. For instance, while Facebook allows users to choose over 50 gender identities to display on their public profile, an investigation into the social media's software revealed that users are filtered into the male-female gender binary within the database for targeted advertising purposes. For another example, pieces of software called bittorrent trackers facilitate the massive distribution of information on Wikipedia. Software facilitates the collective rhetorical action of this encyclopedia.

The field of software studies encourages the investigation into and recognition of software's impacts on people and culture.

People

Online communities

Online communities are groups of people with a common interests that interact and engage over the Internet. Many online communities are found within social networking sites, online forums, and chat rooms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, 4chan, etc., where members can share and discuss information and inquiries. These online spaces often establish their own rules, norms, and culture, and in some cases, users will adopt community-specific terminology or phrases.

Scholars have noted that online communities have especially gained prominence among users like e-patients and victim-survivors of abuse. Within online health and support groups respectively, members have been able to find others who share similar experiences, receive advice and emotional support, and record their own narrative.

However, online communities face issues with online harassment in the form of trolling, cyberbullying, and hate speech. According to the Pew Research Center, 41% of Americans have experienced some form of online harassment with 75% of these experiences occurring over social media. Another area of concern is the influence of algorithms on delineating the online communities a user comes in contact with. Personalizing algorithms can tailor a user's experience to their analytically determined preference, which creates a "filter bubble". The user loses agency in content accessibility and information dissemination when these bubbles are created. The loss of agency can lead to polarization, but recent research indicates that individual level polarization is rare. Most polarization is due to the influx of users with extreme views that can encourage users to move towards partisan fringes from "gateway communities". In summary, online communities support community but in rare cases can support polarization.

Social media

Social media makes human connection formal, manageable, and profitable to social media companies. The technology that promotes this human connection is not human, but automated. As people use social media and form their experiences on the platforms to meet their interests, the technology also affects how the users interact with each other and the world.

Social media also allows for the weaving of "offline and online communities into integrated movements". Users' actions, such as liking, commenting, sending, retweeting or saving a post, contribute to the algorithmic customization of their personalized content. Ultimately, the reach social media has is determined by these algorithms. Social media also offers various image altering tools that can impact image perception – making the platform less human and more automated.

Digital activism

Digital activism serves an agenda-setting function as it can influence mainstream media and news outlets. Hashtags, which curate posts with similar themes and ideas into a central location on a digital platform, aid in bringing exposure to social and political issues. These hashtags, specifically the subsequent discussions they create, put pressure on private institutions and governments to address these issues, as can be seen with movements like #CripTheVote, #BringBackOurGirls, or #MeToo. Many recent social movements have originated on Twitter, as Twitter Topic Networks provide a framework for online community organizing.

Influencers and content creators

As social media is increasingly becoming more available, the influencer/content creator position has also become recognized as a profession. With such a large and rapid consumer presence on social media, it creates both a helpful and overwhelming source of consumer information for advertisers. There is substantial potential to identify "market mavens" on social media due to fandom culture and the nature of influencer/content creator followings. Social media has opened up business opportunities for corporations to employ influencer marketing, where they can more easily find suitable influencers to advertise their products to their viewers.

Online learning

Although online learning existed previously, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic the prevalence of online learning increased. These online learning platforms are known as e-learning management systems (ELMS) and they allow both students and teachers access to a shared, digital space, which includes classroom resources, assignments, discussions, and social networking through direct messaging and email. Although socialization is a component of e-learning management systems, not all students utilize these resources, rather they focus on the lecturer as the primary resource of knowledge. The long-term effects of emergency online learning, which many turned to during the height of the pandemic, is ongoing; however, one study concluded that students' "motivation, self-efficacy, and cognitive engagement decreased after the transition."

Interactive media

Video games

The procedural and interactive nature of video games leads them to be rich examples of procedural rhetoric. This rhetoric can range from games designed to bolster children's learning to challenging one's assumptions of the world around them. An educational video game developed for students at the University of Texas at Austin, titled Rhetorical Peaks, was made with the goal of examining rhetoric's procedural nature and to capture the constantly changing contexts of rhetoric. The open-ended nature of the game as well as the developer's intent on playing the game within a classroom setting encouraged collaboration among students and for them to develop their own interpretations on the game's plot based on vague clues, ultimately helping them to realize that there must be a willingness to change between lines of thought and to work within and past limits in understanding rhetoric.

In mainstream gaming, each game has its own set of language which help shape the way information is transferred between players in their community. With the popularization of online gaming - including games such as Call of Duty, League of Legends, and many more - players have been able to communicate with one another that creates their own rhetoric within the established world of the game, which allows players to influence and be influenced by the other gamers around them. Another well known game called Detroit: Become Human has another way of encouraging digital rhetoric within the gaming community. This decision based video game gives the player the power to create their own story that deals with gender, race, and sexuality. This futuristic message of a human to machine relationship caused discussion due to the difficult moral decisions being made while playing. At the end, there are surveys to take to see others opinions about certain decisions around the world.

Mobile applications

Mobile applications are computer programs designed specifically for mobile devices, such as phones or tablets. Mobile applications cater to a wide range of audiences and needs. There are apps for social media, employment, education, etc. Mobile apps allow for a "cultural hybridity of habit" which allows anyone to stay connected with anyone, anywhere. Due to this, there is always access to changing cultures and lifestyles, since there are so many different apps available to research or publish work. Furthermore, mobile apps allow individual users to manage many aspects of their lives while allowing the apps themselves to be able to continue to largely change and upgrade socially.

Mobility of information poses challenges to user interface, notably the small screen and keys, in comparison to larger counterparts such as laptops and PC's. However, it also has the advantage of heightening physical interactivity with touch, and presents experiences with multiple senses in this way. With these varying factors, mobile applications must identify how they can successfully create user interfaces that motivate trust, reliability, and helpful UX/UI design.

Immersive media

Emerging immersive technologies such as virtual reality removes the visual presence of devices and mimics emotional experiences. User immersion into virtual reality includes simulated real-life communication; virtual reality provides the illusion of being somewhere the body physically is not, which contributes to widespread communication that reaches the point of telepresence and telexistence.

Critical approaches

Technofeminism

Digital rhetoric gives a platform to technofeminism, a concept that brings together the intersections of gender, capitalism, and technology. Technofeminism advocates for equality for women in technology-heavy fields and researches the relationship between women and their devices. Intersectionality is a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw that recognizes the societal injustices based on our identities. It is often challenging for women to navigate finding and interacting in digital spaces without harassment or gender biases. There is an importance of digital activism for unrepresented communities, such as gender non-conforming and transgender people of all races, disabled people, and people of color. In the journal Computers and Composition only five articles explicitly use the term intersectionality or technofeminism. Technofeminism and intersectionality are still not very prevalent when developing new technologies and research.

Digital cultural rhetoric

The expansion of the internet has increased, digital media or rhetoric can be used to represent or identify a culture. Scholars have studied how digital rhetoric is affected by one's personal factors, such as race, religion and sexuality. Due to these factors, people utilize different tools and absorb information differently. Digital culture has created the need for specialized communities on the web. Computer-mediated communities such as Reddit can give a voice to these specialized communities. One can experience and converse with other like-minded people on the web via comment sections and shared online migration. The creation of digital cultural rhetoric has allowed for the use of online slang that other communities may not be aware of. Online communities that explore digital cultural rhetoric allow users to discover their social identity, and confront stereotypes that they were once confronted with.

Embodiment

One subset of digital cultural rhetoric is embodiment—which is the idea that every person has a unique relationship with technology based on their unique set of identities. Studying the relationship between bodies and technology is one way that digital rhetoricians are able to promote equal access and opportunity within the digital sphere. Since technology is considered to be an extension of the real world, users are also shaped by the experiences they have in digital spaces. The artificial interactions that occur in online environments allow users to exist in a way that is additive to their mere human experience.

Pedagogy

With digital rhetoric becoming increasingly present, pedagogical approaches have been proposed by scholars to teach digital rhetoric in the classroom. Courses in digital rhetoric study the intersectionality between users and digital material, as well as how different backgrounds such as age, ethnicity, gender and more can affect these interactions.

Higher education

Several scholars teach digital rhetoric courses at universities in the US, although their approaches vary considerably. Jeff Grabill, a scholar with a background in English, education, and technology, encourages his contemporaries to find a bridge between the scholarly field of digital rhetoric and its implementation. Cheryl Ball specializes in areas that consist of multimodal composition and editing practices, digital media scholarship, digital publishing, and university writing pedagogy. Ball teaches students to write and compose multimodal texts by analyzing rhetorical options and choosing the most appropriate genres, technologies, media, and modes for a particular situation. Multimodality also influenced Elizabeth Losh et al.'s work Understanding Rhetoric: A Graphic Guide to Writing, which emphasizes engaging the comic form of literacy. A similar approach also inspired Melanie Gagich to alter the curriculum of her first-year English course completely, aiming to redefine digital projects as rigorous academic assignments and teach her students necessary audience analysis skills. Such a design ultimately allowed students in Gagich's classroom to develop their creativity and confidence as writers.

In another approach, Douglas Eyman recommends a course in web authoring and design that provides undergraduates more practical instruction in the production and rhetorical understanding of digital texts. Moreover, he explains that web authoring and design for digital rhetoric instruction provides opportunities for students to learn fundamentals of web writing and design conventions, rules and procedures. Similarly, Collin Bjork argues that "integrating digital rhetoric with usability testing can help researchers cultivate a more complex understanding of how students, instructors, and interfaces interact in OWI."

Other scholars focus more on the relationship between digital rhetoric and social impact. Scholars Lori Beth De Hertogh et al. and Angela Haas have published materials discussing intersectionality and digital rhetoric, arguing that the two are inseparable and classes covering digital rhetoric must also explore intersectionality. Lauren Malone has also analyzed the relationship between identity and teaching digital rhetoric through research on QTPoC (Queer and Trans People of Color)'s online engagement. From this research, Malone created a series of steps for digital rhetoric instructors to take in order to foster inclusivity within their classroom Finally, scholar Melanie Kill actively introduces digital rhetoric to college-aged students, arguing for the importance of editing Wikipedia and capitalizing on their privilege of education and access to materials. Similar to De Hertogh et al. and Haas, Kill believes an education in digital rhetoric serves all students, as it facilitates positive social change.

K-12

Many educational systems are framed so that students actively participate in technological systems as designers of digital rhetoric, not passive users. There are three core goals students have identified for their coursework: building their own digital space, learning all aspects of digital rhetoric (including the theory, technology, and uses), and applying it in their own lives. The ecological system generated by the interactions of students with classmates, digital media, and other individuals is the basis of "interconnected" rhetorical processes and shared digital work.

Video games are one avenue students learn to design the rhetoric and code underlying their technological systems. Video game use has evolved rapidly since the 1980s, and current video games have been incorporated into education. Scholar Ian Bogost suggests that video games can be utilized in a multitude of subjects to be studied as models of our non-digital world. Specifically, they note that video games could be used as an "entry point" for students that may not have been interested in computer science to enter that field. Games and game technology enhance learning by operating at the "outer and growing edge of a player's competence". Games challenge students at levels that cause frustration but preserve motivation to solve the challenge at this edge.

Ian Bogost also notes that video games can be taught as rhetorical and expressive in nature, allowing children to model their experiences through programming. When dissected, the ethics and rhetoric in video games' computational systems is exposed. Analysis of video games as an interactive medium reveals the underlying rhetoric through the performative activity of the player. Recognition of procedural rhetoric through course studies reflects how these mediums can augment politics, advertisement, and information. To help address the rhetoric in video game code, scholar Collin Bjork makes a series of recommendations for integrating digital rhetoric with usability testing in online writing instruction.

Some scholars have also identified specific practices for digital rhetoric instruction in pre-collegiate classrooms. As Douglas Eyman points out, students require agency when learning digital rhetoric, meaning instructors designing lessons must allow students to interact with the technology directly and enact change on the design. This is consistent with discoveries by other professors, who claim one of the primary goals of students in a digital rhetoric classroom is to create space for themselves, connections with peers, and deeply understand its significance. These interpersonal connections reflect a "thick correlation between digitalization and empowering pedagogy".

Pre-K

The United States Government's Office of Educational Technology has emphasized four guiding principles when using technology with early learners.

- When used appropriately technology can be a tool for learning

- The use of technology should allow for increased access to learning opportunities for all children

- Technology can be used strengthen relationships between children and their families, early educators and friends

- Technology is most effective when early learners are interacting with adults and peers. Adults can also supervise children online for said effectiveness.

Despite these four pillars most studies conclude that learning technology for children under the age of two is not beneficial. If you must have your young child use technology it is best that the technology is used to promote relationship development, for instance video chat software to connect with loved ones at a distance.

Digital rhetoric as a field of study

In 2009, rhetorician Elizabeth Losh offered this four-part definition of digital rhetoric in her book, Virtualpolitik:

- The conventions of new digital genres that are used for everyday discourse, as well as for special occasions, in average people's lives.

- Public rhetoric, often in the form of political messages from government institutions, that is represented or recorded through digital technology and disseminated via electronically distributed networks.

- The emerging scholarly discipline concerned with the rhetorical interpretation of computer-generated media as objects of study.

- Mathematical theories of communication from the field of information science, many of which attempt to quantify the amount of uncertainty in a given linguistic exchange or the likely paths through which messages travel.

Losh's definition demonstrates that digital rhetoric is a field that relies on different methods to study various types of information, such as code, text, visuals, videos, and so on.

Douglas Eyman suggests that classical theories can be mapped onto digital media but a larger academic focus should be placed on the "extension of rhetorical theory". Careers in developing and analyzing the rhetoric in code a prominent field of study. A journal established in 1985, Computers and Composition, focuses on computers communication and has considered the use of "rhetoric as their conceptual framework" and the digital rhetoric in software development. Moreover, digital rhetoric is a tool by which different cultures can continue to facilitate their longstanding cultural traditions. In his book, Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age, Adam J. Banks states that modern day storytellers, like stand-up comics and spoken word poets, give African American rhetoric a flexible approach that is still true to tradition. While digital rhetoric can be used to facilitate traditions, select cultures face several practical application issues. Radhika Gajjala, professor at the University of Pittsburgh, writes that South Asian cyber feminists face issues with regards to building their web presence. Studies on how digital rhetoric implicates various topics are ongoing and encompass many fields.

Social issues

Access

Referred to as the digital divide, issues of economic access and user-level access are recurring issues in digital rhetoric. These issues show up most prevalently in computers and writing circles though the digital divide impacts a multitude of online forums, user bases, and communities. A lack of access can refer to inequality in obtaining information, means of communication, and opportunities. For many that teach digital rhetoric in schools and universities, student access to technologies at home and in school is an operative concern. There is some debate about whether mobile computing devices like smartphones make technology access more equitable. In addition, the socioeconomic divide that is created due to accessibility is a major factor of digital rhetoric. For instance, NIH researcher and a professor of education at Stanford University, Linda Darling-Hammond discusses the lack of educational resources that children of color in America face. Further, Angela M. Haas, author of "Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice", describes access in a more theoretical way. Her text explains that through access one can connect a physical body with the digital space. Technology diffusion can also a contributing factor, which refers to how the market for new technology changes over time and how that influences technology use and production across society. Studies conducted by scholar Sunil Wattal conclude that technology diffusion mimics social class status. As such, technology diffusion varies from community to community, making it a much greater challenge to ensure access equity across classes. These examples preface the topic that access encompasses every aspect of ones life and must be perceived as such. If accessibility is not resolved at a foundational level then social discrimination will be further perpetuated.

Another issue of access comes in the form of paywalls, which can be a major hindrance for education and reduce accessibility to many educational tools and materials. This practice can increase barriers to scholarship and limit information that is open access. This industry has gotten flack for its long history of monopolizing the publishing market and forcing universities to pay over $11 million annually for access to certain works. Open access has removed the barriers of fees associated with accessing a work and the restrictions of copyright and licensing. The matter of eliminating fees is most prevalent to digital rhetoric because it allows for more equal access to works. Open access and digital rhetoric do not eliminate copyright, but they eliminate restrictions by giving authors the choice to maintain their right to copy and distribute their materials however they choose, or they may turn the rights over to a specific journal. Digital rhetoric involves works that are found online and open access is allowing more people to be able to reach these works.

Politics

The increase in digitalization of media has amplified the importance influence of digital rhetoric in politics, as this digitalization has introduced a new, more direct relationship between politicians and the citizenry. Digital communication platforms and social networking sites allow citizens to share information and engage in debate with other people of similar or distinct political ideologies, which have been shown to influence and predict the political behavior of individuals outside the digital world. Politicians have been known to use digital rhetoric as a persuasive tool to communicate information to citizens. Reciprocally, digital rhetoric has enabled increasing political participation amongst citizens. Theoretical research on digital rhetoric in politics has attributed the increase of political participation to three models: the motivation model, the learning model, and the attitude model.

- The motivation model proposes that digital rhetoric has decreased the opportunity costs of participating in politics since it makes information readily available to the people.

- The learning model established the increase in political participation to the vast amount of political information available on the internet which increases the inclusion of the citizens in the political process.

- The attitude model extended from the previous two by suggesting that digital rhetoric has changed the perception of citizens towards politics, particularly by providing interactive tools that allow people to engage in the political process.

Online harassment

Online harassment has steadily been on the rise since the rise of social media. As the number of platforms meant for communicating have increased, so has the a digital rhetoric that includes an abundance of bullying. Analysis linked cyberbullying-specific behaviors, including perpetration and victimization, to a number of detrimental psychosocial outcomes. The trend of people posting about the characters and their lifestyles reinforces the iconography of stereotypes (such as "hillbillies"), which is successful because of the way in which the rhetoric of difference is a naturalized component of the ethnic and racial identity. These issues led the first Cyberbullying Prevention campaign, STOMP Out Bullying, to launch itself in 2005. Like the abundance of campaigns that would form in the next fifteen years, it focuses on creating cyberbullying awareness and reducing and preventing bullying.

The challenge with social media has increased since the rise of 'cancel culture', which aims to end the career of a culprit through any means possible, mainly the boycott of their works. There is a limited number of characters to convey the message, (ex: Twitter's 280 character limit) so messages in digital rhetoric tend to be scarcely explained, allowing stereotypes to flourish. Erika Sparby theorized that the ability to be anonymous and use pseudonyms or avatars on social media gives users more confidence to address either someone or something in a negative light.

More recently, techniques utilizing machine learning and artificial intelligence have become popular in synthesizing fake, realistic videos of people whose faces are swapped out with others people's faces. These kinds of videos, originally referred to as "deepfakes" by one user in the popular chatting forum Reddit, can be created by easily obtainable and simple software, inciting concerns that people may use the software to blackmail or bully people online. A large quantity of images containing faces are required to create a deepfake. In addition, specific types of characteristics, such as different exposure and color levels, need to be consistent to make a realistic video. However, given the vast amounts of photos of people publicly available on the internet from social media sites, there is concern about the extent to which people can use deepfakes as a bullying tactic. There have already been multiple incidents of this kind of harassment being used to bully people, one notable one involving a mother who used deepfake software to frame a few of her daughter's classmates at school by producing fake videos of them in pornographic videos. Due to AI and machine learning being relatively new sub fields of computer science and mathematics, there has not been enough time for deepfake video detection technologies to mature, and are so far only detectable using the human eye to spot irregularities in movement of the people in the videos.

Misinformation and disinformation

While digital rhetoric can often be used to persuade, in some cases, it is used to spread false and inaccurate information. The proliferation of illegitimate information over the internet has given rise to the term misinformation, which is defined as the spread of false claims that may or may not be intended to mislead others. This is not to be confused with disinformation, which is illegitimate or inaccurate information that is spread with the intent to mislead others. Both misinformation and disinformation have had detrimental impacts on the knowledge, perceptions, and, in some cases, actions of many susceptible individuals. Social media specifically has greatly impacted the spread of false information. Scientific facts, such as the damaging environmental impacts of global warming, now come into question on a daily basis.

Social media has contributed to the proliferation of misinformation/disinformation because of its viral and largely unfiltered nature. Everyday users have the power to join and perpetuate a narrative that could be entirely false. In recent years, the term "fake news"— used synonymously with misinformation— has been highly popularized and politicized in digital spaces. The effects of misinformation were further on display during the United States' 2020 presidential election, where social media usage had an impact on Congress. Starting as early as April 2020, then-President Donald Trump tweeted about the dangers of widespread mail voting fraud even though studies have shown that mail voting fraud is rare and the dangers are negligible. Even after losing the election, Trump continued to use Twitter as his main platform to speak about rigged elections, mail-in voter fraud, and other proven falsehoods. On January 6, 2021, Congress was set to certify the results of the 2020 election whilst a rally of Trump supporters were protesting the election results based on Trump's claims of fraud. This assembly of his supporters quickly turned violent, as a mob stormed the Capitol with the intent to overturn election results. The insurrection, which killed five people, was the culmination of Trump's long thread of disinformation spread on social media. As a result, Trump was permanently suspended from Twitter two days later because his involvement in the insurrection violated Twitter's terms and conditions regarding the "glorification of violence". Alongside being suspend from other major social media sites such as Facebook and YouTube, Trump was impeached by the House of Representatives because of his incitement of the insurrection. This incident started a heated debate about social media companies' abilities to limit free speech, but ultimately, these companies are still private businesses who are allowed to determine their own terms and conditions as they see fit, which users must agree to in order to use these platforms in the first place.

Legitimacy

There is controversy regarding the innovative nature of digital rhetoric. Arguments opposed to legitimizing web text are Platonically based, in that they reject the new form of scholarship—web text, and praise the old form—print, in the same way that oral communication was originally favored over written communication. Originally some traditionalists did not regard online open-access journals with the same legitimacy as print journals for this reason; however, digital arenas have become the primary place for disseminating academic information in many areas of scholarship. Modern scholars struggle to "claim academic legitimacy" in these new media forms, as the tendency of pedagogy is to write about a subject rather than actively work in it. Within the past decade, more scholarly texts have been openly accessible, which provides an innovative way for students to gain access to textual materials online for free, in the way that many scholarly journals like Kairos, Harlot of the Arts, and Enculturation are already available through open access.

COVID-19 pandemic

Most recently, the persistence of the global COVID-19 pandemic since 2020 has changed both physical and digital spaces. This global change has profoundly affected many aspects of human existence. The resulting isolation and economic shutdowns complicated existing issues and created a new set of globalized challenges as it "imposed" a change to the "psychosocial environment". The virus has forced the majority of individuals with internet access to depend on technology in order to remain connected to the outside world, and on a larger scale, global economies have become reliant on transitioning business to digital platforms. Also, the pandemic forced schools across the globe to switch to an "online only" approach. By March 25, 2020, all school systems in the United States closed indefinitely. In search of a platform to host online learning, many schools incorporated popular video chat service Zoom as their method of providing socially distant instruction. In April 2020, Zoom was hosting over 300 million daily meetings, as opposed to 10 million in December 2019. While some may view online learning as a drop in education quality, the shift to online learning demonstrated the current state of accessibility to digital information while promoting the use of digital learning through Zoom meetings, YouTube videos, and broadcasting systems such as Open Broadcaster Software. However, there have also been questions about whether or not the switch to online learning has also had detrimental impacts on students, and it has been difficult to transition younger students in particular to completely online models of learning.

The pandemic has also contributed to creating misleading rhetoric in online spaced. Heightened public health concerns combined with the accessibility of social media led to both misinformation and disinformation regarding COVID-19 to spread rapidly. Some people online theorized that the deadly virus could be cured upon the ingestion of bleach, while others believed the disease to have been intentionally started by China in an attempt to take over the world. Trump also supported taking Hydroxychloroquine to prevent the contraction of COVID-19. The World Health Organization (WHO) has advised on numerous occasions that the drug has no signs of preventing the spread of the virus. Despite their illegitimate nature, these conspiracy theories have spread rapidly in digital spaces. As a result, the WHO declared the proliferation of misinformation regarding the virus an "infodemic". This label caused most social media sites to strengthen their policies relating to false information, but many misleading claims still slip through the cracks.