Evolutionary taxonomy, evolutionary systematics or Darwinian classification is a branch of biological classification that seeks to classify organisms using a combination of phylogenetic relationship (shared descent), progenitor-descendant relationship (serial descent), and degree of evolutionary change. This type of taxonomy may consider whole taxa rather than single species, so that groups of species can be inferred as giving rise to new groups. The concept found its most well-known form in the modern evolutionary synthesis of the early 1940s.

Evolutionary taxonomy differs from strict pre-Darwinian Linnaean taxonomy (producing orderly lists only), in that it builds evolutionary trees. While in phylogenetic nomenclature each taxon must consist of a single ancestral node and all its descendants, evolutionary taxonomy allows for groups to be excluded from their parent taxa (e.g. dinosaurs are not considered to include birds, but to have given rise to them), thus permitting paraphyletic taxa.

Origin of evolutionary taxonomy

Evolutionary taxonomy arose as a result of the influence of the theory of evolution on Linnaean taxonomy. The idea of translating Linnaean taxonomy into a sort of dendrogram of the Animal and Plant Kingdoms was formulated toward the end of the 18th century, well before Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species was published. The first to suggest that organisms had common descent was Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis in his 1751 Essai de Cosmologie, Transmutation of species entered wider scientific circles with Erasmus Darwin's 1796 Zoönomia and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's 1809 Philosophie Zoologique. The idea was popularised in the English-speaking world by the speculative but widely read Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published anonymously by Robert Chambers in 1844.

Following the appearance of On the Origin of Species, Tree of Life representations became popular in scientific works. In On the Origin of Species, the ancestor remained largely a hypothetical species; Darwin was primarily occupied with showing the principle, carefully refraining from speculating on relationships between living or fossil organisms and using theoretical examples only. In contrast, Chambers had proposed specific hypotheses, the evolution of placental mammals from marsupials, for example.

Following Darwin's publication, Thomas Henry Huxley used the fossils of Archaeopteryx and Hesperornis to argue that the birds are descendants of the dinosaurs. Thus, a group of extant animals could be tied to a fossil group. The resulting description, that of dinosaurs "giving rise to" or being "the ancestors of" birds, exhibits the essential hallmark of evolutionary taxonomic thinking.

The past three decades have seen a dramatic increase in the use of DNA sequences for reconstructing phylogeny and a parallel shift in emphasis from evolutionary taxonomy towards Hennig's 'phylogenetic systematics'.

Today, with the advent of modern genomics, scientists in every branch of biology make use of molecular phylogeny to guide their research. One common method is multiple sequence alignment.

Cavalier-Smith, G. G. Simpson and Ernst Mayr are some representative evolutionary taxonomists.

New methods in modern evolutionary systematics

Efforts in combining modern methods of cladistics, phylogenetics, and DNA analysis with classical views of taxonomy have recently appeared. Certain authors have found that phylogenetic analysis is acceptable scientifically as long as paraphyly at least for certain groups is allowable. Such a stance is promoted in papers by Tod F. Stuessy and others. A particularly strict form of evolutionary systematics has been presented by Richard H. Zander in a number of papers, but summarized in his "Framework for Post-Phylogenetic Systematics".

Briefly, Zander's pluralistic systematics is based on the incompleteness of each of the theories: A method that cannot falsify a hypothesis is as unscientific as a hypothesis that cannot be falsified. Cladistics generates only trees of shared ancestry, not serial ancestry. Taxa evolving seriatim cannot be dealt with by analyzing shared ancestry with cladistic methods. Hypotheses such as adaptive radiation from a single ancestral taxon cannot be falsified with cladistics. Cladistics offers a way to cluster by trait transformations but no evolutionary tree can be entirely dichotomous. Phylogenetics posits shared ancestral taxa as causal agents for dichotomies yet there is no evidence for the existence of such taxa. Molecular systematics uses DNA sequence data for tracking evolutionary changes, thus paraphyly and sometimes phylogenetic polyphyly signal ancestor-descendant transformations at the taxon level, but otherwise molecular phylogenetics makes no provision for extinct paraphyly. Additional transformational analysis is needed to infer serial descent.

The Besseyan cactus or commagram is the best evolutionary tree for showing both shared and serial ancestry. First, a cladogram or natural key is generated. Generalized ancestral taxa are identified and specialized descendant taxa are noted as coming off the lineage with a line of one color representing the progenitor through time. A Besseyan cactus or commagram is then devised that represents both shared and serial ancestry. Progenitor taxa may have one or more descendant taxa. Support measures in terms of Bayes factors may be given, following Zander's method of transformational analysis using decibans.

Cladistic analysis groups taxa by shared traits but incorporates a dichotomous branching model borrowed from phenetics. It is essentially a simplified dichotomous natural key, although reversals are tolerated. The problem, of course, is that evolution is not necessarily dichotomous. An ancestral taxon generating two or more descendants requires a longer, less parsimonious tree. A cladogram node summarizes all traits distal to it, not of any one taxon, and continuity in a cladogram is from node to node, not taxon to taxon. This is not a model of evolution, but is a variant of hierarchical cluster analysis (trait changes and non-ultrametric branches. This is why a tree based solely on shared traits is not called an evolutionary tree but merely a cladistic tree. This tree reflects to a large extent evolutionary relationships through trait transformations but ignores relationships made by species-level transformation of extant taxa.

Phylogenetics attempts to inject a serial element by postulating ad hoc, undemonstrable shared ancestors at each node of a cladistic tree. There are in number, for a fully dichotomous cladogram, one less invisible shared ancestor than the number of terminal taxa. We get, then, in effect a dichotomous natural key with an invisible shared ancestor generating each couplet. This cannot imply a process-based explanation without justification of the dichotomy, and supposition of the shared ancestors as causes. The cladistic form of analysis of evolutionary relationships cannot falsify any genuine evolutionary scenario incorporating serial transformation, according to Zander.

Zander has detailed methods for generating support measures for molecular serial descent and for morphological serial descent using Bayes factors and sequential Bayes analysis through Turing deciban or Shannon informational bit addition.

The Tree of Life

As more and more fossil groups were found and recognized in the late 19th and early 20th century, palaeontologists worked to understand the history of animals through the ages by linking together known groups. The Tree of life was slowly being mapped out, with fossil groups taking up their position in the tree as understanding increased.

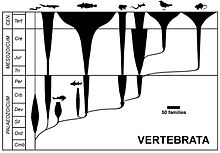

These groups still retained their formal Linnaean taxonomic ranks. Some of them are paraphyletic in that, although every organism in the group is linked to a common ancestor by an unbroken chain of intermediate ancestors within the group, some other descendants of that ancestor lie outside the group. The evolution and distribution of the various taxa through time is commonly shown as a spindle diagram (often called a Romerogram after the American palaeontologist Alfred Romer) where various spindles branch off from each other, with each spindle representing a taxon. The width of the spindles are meant to imply the abundance (often number of families) plotted against time.

Vertebrate palaeontology had mapped out the evolutionary sequence of vertebrates as currently understood fairly well by the closing of the 19th century, followed by a reasonable understanding of the evolutionary sequence of the plant kingdom by the early 20th century. The tying together of the various trees into a grand Tree of Life only really became possible with advancements in microbiology and biochemistry in the period between the World Wars.

Terminological difference

The two approaches, evolutionary taxonomy and the phylogenetic systematics derived from Willi Hennig, differ in the use of the word "monophyletic". For evolutionary systematicists, "monophyletic" means only that a group is derived from a single common ancestor. In phylogenetic nomenclature, there is an added caveat that the ancestral species and all descendants should be included in the group. The term "holophyletic" has been proposed for the latter meaning. As an example, amphibians are monophyletic under evolutionary taxonomy, since they have arisen from fishes only once. Under phylogenetic taxonomy, amphibians do not constitute a monophyletic group in that the amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals) have evolved from an amphibian ancestor and yet are not considered amphibians. Such paraphyletic groups are rejected in phylogenetic nomenclature, but are considered a signal of serial descent by evolutionary taxonomists.