The Kerr metric or Kerr geometry describes the geometry of empty spacetime around a rotating uncharged axially symmetric black hole with a quasispherical event horizon. The Kerr metric is an exact solution of the Einstein field equations of general relativity; these equations are highly non-linear, which makes exact solutions very difficult to find.

Overview

The Kerr metric is a generalization to a rotating body of the Schwarzschild metric, discovered by Karl Schwarzschild in 1915, which described the geometry of spacetime around an uncharged, spherically symmetric, and non-rotating body. The corresponding solution for a charged, spherical, non-rotating body, the Reissner–Nordström metric, was discovered soon afterwards (1916–1918). However, the exact solution for an uncharged, rotating black hole, the Kerr metric, remained unsolved until 1963, when it was discovered by Roy Kerr. The natural extension to a charged, rotating black hole, the Kerr–Newman metric, was discovered shortly thereafter in 1965. These four related solutions may be summarized by the following table, where Q represents the body's electric charge and J represents its spin angular momentum:

Non-rotating (J = 0) Rotating (J ≠ 0) Uncharged (Q = 0) Schwarzschild Kerr Charged (Q ≠ 0) Reissner–Nordström Kerr–Newman

According to the Kerr metric, a rotating body should exhibit frame-dragging (also known as Lense–Thirring precession), a distinctive prediction of general relativity. The first measurement of this frame dragging effect was done in 2011 by the Gravity Probe B experiment. Roughly speaking, this effect predicts that objects coming close to a rotating mass will be entrained to participate in its rotation, not because of any applied force or torque that can be felt, but rather because of the swirling curvature of spacetime itself associated with rotating bodies. In the case of a rotating black hole, at close enough distances, all objects – even light – must rotate with the black hole; the region where this holds is called the ergosphere.

The light from distant sources can travel around the event horizon several times (if close enough); creating multiple images of the same object. To a distant viewer, the apparent perpendicular distance between images decreases at a factor of e2π (about 500). However, fast spinning black holes have less distance between multiplicity images.

Rotating black holes have surfaces where the metric seems to have apparent singularities; the size and shape of these surfaces depends on the black hole's mass and angular momentum. The outer surface encloses the ergosphere and has a shape similar to a flattened sphere. The inner surface marks the event horizon; objects passing into the interior of this horizon can never again communicate with the world outside that horizon. However, neither surface is a true singularity, since their apparent singularity can be eliminated in a different coordinate system. A similar situation obtains when considering the Schwarzschild metric which also appears to result in a singularity at dividing the space above and below rs into two disconnected patches; using a different coordinate transformation one can then relate the extended external patch to the inner patch (see Schwarzschild metric § Singularities and black holes) – such a coordinate transformation eliminates the apparent singularity where the inner and outer surfaces meet. Objects between these two surfaces must co-rotate with the rotating black hole, as noted above; this feature can in principle be used to extract energy from a rotating black hole, up to its invariant mass energy, Mc2.

The LIGO experiment that first detected gravitational waves, announced in 2016, also provided the first direct observation of a pair of Kerr black holes.

Metric

The Kerr metric is commonly expressed in one of two forms, the Boyer–Lindquist form and the Kerr–Schild form. It can be readily derived from the Schwarzschild metric, using the Newman–Janis algorithm by Newman–Penrose formalism (also known as the spin–coefficient formalism), Ernst equation, or Ellipsoid coordinate transformation.

Boyer–Lindquist coordinates

The Kerr metric describes the geometry of spacetime in the vicinity of a mass rotating with angular momentum . The metric (or equivalently its line element for proper time) in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates is

| (1) |

where the coordinates are standard oblate spheroidal coordinates, which are equivalent to the cartesian coordinates

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where is the Schwarzschild radius

| (5) |

and where for brevity, the length scales and have been introduced as

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

A key feature to note in the above metric is the cross-term . This implies that there is coupling between time and motion in the plane of rotation that disappears when the black hole's angular momentum goes to zero.

In the non-relativistic limit where (or, equivalently, ) goes to zero, the Kerr metric becomes the orthogonal metric for the oblate spheroidal coordinates

| (9) |

Kerr–Schild coordinates

The Kerr metric can be expressed in "Kerr–Schild" form, using a particular set of Cartesian coordinates as follows. These solutions were proposed by Kerr and Schild in 1965.

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Notice that k is a unit 3-vector, making the 4-vector a null vector, with respect to both g and η. Here M is the constant mass of the spinning object, η is the Minkowski tensor, and a is a constant rotational parameter of the spinning object. It is understood that the vector is directed along the positive z-axis. The quantity r is not the radius, but rather is implicitly defined by

| (14) |

Notice that the quantity r becomes the usual radius R

when the rotational parameter approaches zero. In this form of solution, units are selected so that the speed of light is unity (). At large distances from the source (R ≫ a), these equations reduce to the Eddington–Finkelstein form of the Schwarzschild metric.

In the Kerr–Schild form of the Kerr metric, the determinant of the metric tensor is everywhere equal to negative one, even near the source.

Soliton coordinates

As the Kerr metric (along with the Kerr–NUT metric) is axially symmetric, it can be cast into a form to which the Belinski–Zakharov transform can be applied. This implies that the Kerr black hole has the form of a gravitational soliton.

Mass of rotational energy

If the complete rotational energy of a black hole is extracted, for example with the Penrose process, the remaining mass cannot shrink below the irreducible mass. Therefore, if a black hole rotates with the spin , its total mass-equivalent is higher by a factor of in comparison with a corresponding Schwarzschild black hole where is equal to . The reason for this is that in order to get a static body to spin, energy needs to be applied to the system. Because of the mass–energy equivalence this energy also has a mass-equivalent, which adds to the total mass–energy of the system, .

The total mass equivalent (the gravitating mass) of the body (including its rotational energy) and its irreducible mass are related by

Wave operator

Since even a direct check on the Kerr metric involves cumbersome calculations, the contravariant components of the metric tensor in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates are shown below in the expression for the square of the four-gradient operator:

| (15) |

Frame dragging

We may rewrite the Kerr metric (1) in the following form:

| (16) |

This metric is equivalent to a co-rotating reference frame that is rotating with angular speed Ω that depends on both the radius r and the colatitude θ, where Ω is called the Killing horizon.

| (17) |

Thus, an inertial reference frame is entrained by the rotating central mass to participate in the latter's rotation; this is called frame-dragging, and has been tested experimentally. Qualitatively, frame-dragging can be viewed as the gravitational analog of electromagnetic induction. An "ice skater", in orbit over the equator and rotationally at rest with respect to the stars, extends her arms. The arm extended toward the black hole will be torqued spinward. The arm extended away from the black hole will be torqued anti-spinward. She will therefore be rotationally sped up, in a counter-rotating sense to the black hole. This is the opposite of what happens in everyday experience. If she is already rotating at a certain speed when she extends her arms, inertial effects and frame-dragging effects will balance and her spin will not change. Due to the equivalence principle, gravitational effects are locally indistinguishable from inertial effects, so this rotation rate, at which when she extends her arms nothing happens, is her local reference for non-rotation. This frame is rotating with respect to the fixed stars and counter-rotating with respect to the black hole. A useful metaphor is a planetary gear system with the black hole being the sun gear, the ice skater being a planetary gear and the outside universe being the ring gear. This can also be interpreted through Mach's principle.

Important surfaces

There are several important surfaces in the Kerr metric (1). The inner surface corresponds to an event horizon similar to that observed in the Schwarzschild metric; this occurs where the purely radial component grr of the metric goes to infinity. Solving the quadratic equation 1/grr = 0 yields the solution:

which in natural units (that give ) simplifies to:

While in the Schwarzschild metric the event horizon is also the place where the purely temporal component gtt of the metric changes sign from positive to negative, in Kerr metric that happens at a different distance. Again solving a quadratic equation gtt = 0 yields the solution:

or in natural units:

Due to the cos2θ term in the square root, this outer surface resembles a flattened sphere that touches the inner surface at the poles of the rotation axis, where the colatitude θ equals 0 or π; the space between these two surfaces is called the ergosphere. Within this volume, the purely temporal component gtt is negative, i.e., acts like a purely spatial metric component. Consequently, particles within this ergosphere must co-rotate with the inner mass, if they are to retain their time-like character. A moving particle experiences a positive proper time along its worldline, its path through spacetime. However, this is impossible within the ergosphere, where gtt is negative, unless the particle is co-rotating around the interior mass with an angular speed at least of . Thus, no particle can move in the direction opposite to central mass's rotation within the ergosphere.

As with the event horizon in the Schwarzschild metric, the apparent singularity at rH is due to the choice of coordinates (i.e., it is a coordinate singularity). In fact, the spacetime can be smoothly continued through it by an appropriate choice of coordinates. In turn, the outer boundary of the ergosphere at rE is not singular by itself even in Kerr coordinates due to non-zero term.

Ergosphere and the Penrose process

A black hole in general is surrounded by a surface, called the event horizon and situated at the Schwarzschild radius for a nonrotating black hole, where the escape velocity is equal to the velocity of light. Within this surface, no observer/particle can maintain itself at a constant radius. It is forced to fall inwards, and so this is sometimes called the static limit.

A rotating black hole has the same static limit at its event horizon but there is an additional surface outside the event horizon named the "ergosurface" given by

in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates, which can be intuitively characterized as the sphere where "the rotational velocity of the surrounding space" is dragged along with the velocity of light. Within this sphere the dragging is greater than the speed of light, and any observer/particle is forced to co-rotate.

The region outside the event horizon but inside the surface where the rotational velocity is the speed of light, is called the ergosphere (from Greek ergon meaning work). Particles falling within the ergosphere are forced to rotate faster and thereby gain energy. Because they are still outside the event horizon, they may escape the black hole. The net process is that the rotating black hole emits energetic particles at the cost of its own total energy. The possibility of extracting spin energy from a rotating black hole was first proposed by the mathematician Roger Penrose in 1969 and is thus called the Penrose process. Rotating black holes in astrophysics are a potential source of large amounts of energy and are used to explain energetic phenomena, such as gamma-ray bursts.

Features of the Kerr geometry

The Kerr geometry exhibits many noteworthy features: the maximal analytic extension includes a sequence of asymptotically flat exterior regions, each associated with an ergosphere, stationary limit surfaces, event horizons, Cauchy horizons, closed timelike curves, and a ring-shaped curvature singularity. The geodesic equation can be solved exactly in closed form. In addition to two Killing vector fields (corresponding to time translation and axisymmetry), the Kerr geometry admits a remarkable Killing tensor. There is a pair of principal null congruences (one ingoing and one outgoing). The Weyl tensor is algebraically special, in fact it has Petrov type D. The global structure is known. Topologically, the homotopy type of the Kerr spacetime can be simply characterized as a line with circles attached at each integer point.

Note that the inner Kerr geometry is unstable with regard to perturbations in the interior region. This instability means that although the Kerr metric is axis-symmetric, a black hole created through gravitational collapse may not be so. This instability also implies that many of the features of the Kerr geometry described above may not be present inside such a black hole.

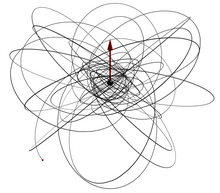

A surface on which light can orbit a black hole is called a photon sphere. The Kerr solution has infinitely many photon spheres, lying between an inner one and an outer one. In the nonrotating, Schwarzschild solution, with , the inner and outer photon spheres degenerate, so that there is only one photon sphere at a single radius. The greater the spin of a black hole, the farther from each other the inner and outer photon spheres move. A beam of light traveling in a direction opposite to the spin of the black hole will circularly orbit the hole at the outer photon sphere. A beam of light traveling in the same direction as the black hole's spin will circularly orbit at the inner photon sphere. Orbiting geodesics with some angular momentum perpendicular to the axis of rotation of the black hole will orbit on photon spheres between these two extremes. Because the spacetime is rotating, such orbits exhibit a precession, since there is a shift in the variable after completing one period in the variable.

Trajectory equations

The equations of motion for test particles in the Kerr spacetime are governed by four constants of motion. The first is the invariant mass of the test particle, defined by the relation where is the four-momentum of the particle. Furthermore, there are two constants of motion given by the time translation and rotation symmetries of Kerr spacetime, the energy , and the component of the orbital angular momentum parallel to the spin of the black hole . and

Using Hamilton–Jacobi theory, Brandon Carter showed that there exists a fourth constant of motion, , now referred to as the Carter constant. It is related to the total angular momentum of the particle and is given by

Since there are four (independent) constants of motion for degrees of freedom, the equations of motion for a test particle in Kerr spacetime are integrable.

Using these constants of motion, the trajectory equations for a test particle can be written (using natural units of ), with

where is an affine parameter such that . In particular, when the affine parameter , is related to the proper time through .

Because of the frame-dragging-effect, a zero-angular-momentum observer (ZAMO) is corotating with the angular velocity which is defined with respect to the bookkeeper's coordinate time . The local velocity of the test-particle is measured relative to a probe corotating with . The gravitational time-dilation between a ZAMO at fixed and a stationary observer far away from the mass is In Cartesian Kerr–Schild coordinates, the equations for a photon are[32] where is analogous to Carter's constant and is a useful quantity

If we set , the Schwarzschild geodesics are restored.

Symmetries

The group of isometries of the Kerr metric is the subgroup of the ten-dimensional Poincaré group which takes the two-dimensional locus of the singularity to itself. It retains the time translations (one dimension) and rotations around its axis of rotation (one dimension). Thus it has two dimensions. Like the Poincaré group, it has four connected components: the component of the identity; the component which reverses time and longitude; the component which reflects through the equatorial plane; and the component that does both.

In physics, symmetries are typically associated with conserved constants of motion, in accordance with Noether's theorem. As shown above, the geodesic equations have four conserved quantities: one of which comes from the definition of a geodesic, and two of which arise from the time translation and rotation symmetry of the Kerr geometry. The fourth conserved quantity does not arise from a symmetry in the standard sense and is commonly referred to as a hidden symmetry.

Overextreme Kerr solutions

The location of the event horizon is determined by the larger root of . When (i.e. ), there are no (real valued) solutions to this equation, and there is no event horizon. With no event horizons to hide it from the rest of the universe, the black hole ceases to be a black hole and will instead be a naked singularity.

Kerr black holes as wormholes

Although the Kerr solution appears to be singular at the roots of , these are actually coordinate singularities, and, with an appropriate choice of new coordinates, the Kerr solution can be smoothly extended through the values of corresponding to these roots. The larger of these roots determines the location of the event horizon, and the smaller determines the location of a Cauchy horizon. A (future-directed, time-like) curve can start in the exterior and pass through the event horizon. Once having passed through the event horizon, the coordinate now behaves like a time coordinate, so it must decrease until the curve passes through the Cauchy horizon.

The region beyond the Cauchy horizon has several surprising features. The coordinate again behaves like a spatial coordinate and can vary freely. The interior region has a reflection symmetry, so that a (future-directed time-like) curve may continue along a symmetric path, which continues through a second Cauchy horizon, through a second event horizon, and out into a new exterior region which is isometric to the original exterior region of the Kerr solution. The curve could then escape to infinity in the new region or enter the future event horizon of the new exterior region and repeat the process. This second exterior is sometimes thought of as another universe. On the other hand, in the Kerr solution, the singularity is a ring, and the curve may pass through the center of this ring. The region beyond permits closed time-like curves. Since the trajectory of observers and particles in general relativity are described by time-like curves, it is possible for observers in this region to return to their past. This interior solution is not likely to be physical and considered as a purely mathematical artefact.

While it is expected that the exterior region of the Kerr solution is stable, and that all rotating black holes will eventually approach a Kerr metric, the interior region of the solution appears to be unstable, much like a pencil balanced on its point. This is related to the idea of cosmic censorship.

Relation to other exact solutions

The Kerr geometry is a particular example of a stationary axially symmetric vacuum solution to the Einstein field equation. The family of all stationary axially symmetric vacuum solutions to the Einstein field equation are the Ernst vacuums.

The Kerr solution is also related to various non-vacuum solutions which model black holes. For example, the Kerr–Newman electrovacuum models a (rotating) black hole endowed with an electric charge, while the Kerr–Vaidya null dust models a (rotating) hole with infalling electromagnetic radiation.

The special case of the Kerr metric yields the Schwarzschild metric, which models a nonrotating black hole which is static and spherically symmetric, in the Schwarzschild coordinates. (In this case, every Geroch moment but the mass vanishes.)

The interior of the Kerr geometry, or rather a portion of it, is locally isometric to the Chandrasekhar–Ferrari CPW vacuum, an example of a colliding plane wave model. This is particularly interesting, because the global structure of this CPW solution is quite different from that of the Kerr geometry, and in principle, an experimenter could hope to study the geometry of (the outer portion of) the Kerr interior by arranging the collision of two suitable gravitational plane waves.

Multipole moments

Each asymptotically flat Ernst vacuum can be characterized by giving the infinite sequence of relativistic multipole moments, the first two of which can be interpreted as the mass and angular momentum of the source of the field. There are alternative formulations of relativistic multipole moments due to Hansen, Thorne, and Geroch, which turn out to agree with each other. The relativistic multipole moments of the Kerr geometry were computed by Hansen; they turn out to be

Thus, the special case of the Schwarzschild vacuum () gives the "monopole point source" of general relativity.

Weyl multipole moments arise from treating a certain metric function (formally corresponding to Newtonian gravitational potential) which appears the Weyl–Papapetrou chart for the Ernst family of all stationary axisymmetric vacuum solutions using the standard euclidean scalar multipole moments. They are distinct from the moments computed by Hansen, above. In a sense, the Weyl moments only (indirectly) characterize the "mass distribution" of an isolated source, and they turn out to depend only on the even order relativistic moments. In the case of solutions symmetric across the equatorial plane the odd order Weyl moments vanish. For the Kerr vacuum solutions, the first few Weyl moments are given by

In particular, we see that the Schwarzschild vacuum has nonzero second order Weyl moment, corresponding to the fact that the "Weyl monopole" is the Chazy–Curzon vacuum solution, not the Schwarzschild vacuum solution, which arises from the Newtonian potential of a certain finite length uniform density thin rod.

In weak field general relativity, it is convenient to treat isolated sources using another type of multipole, which generalize the Weyl moments to mass multipole moments and momentum multipole moments, characterizing respectively the distribution of mass and of momentum of the source. These are multi-indexed quantities whose suitably symmetrized and anti-symmetrized parts can be related to the real and imaginary parts of the relativistic moments for the full nonlinear theory in a rather complicated manner.

Perez and Moreschi have given an alternative notion of "monopole solutions" by expanding the standard NP tetrad of the Ernst vacuums in powers of (the radial coordinate in the Weyl–Papapetrou chart). According to this formulation:

- the isolated mass monopole source with zero angular momentum is the Schwarzschild vacuum family (one parameter),

- the isolated mass monopole source with radial angular momentum is the Taub–NUT vacuum family (two parameters; not quite asymptotically flat),

- the isolated mass monopole source with axial angular momentum is the Kerr vacuum family (two parameters).

In this sense, the Kerr vacuums are the simplest stationary axisymmetric asymptotically flat vacuum solutions in general relativity.

![{\displaystyle {\ddot {x}}+i{\ddot {y}}=4iMa{\frac {r}{\Sigma ^{2}}}W\left[{\dot {x}}+i{\dot {y}}-{\frac {x+iy}{r}}{\dot {r}}\right]-M(x+iy)\left({\frac {4r^{2}}{\Sigma }}-1\right){\frac {C-a^{2}W^{2}}{r\Sigma ^{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6fe5085203cdf9ef96c35da0c12f7ef468f7e0c4)

![{\displaystyle M_{n}=M[ia]^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/893371be1a5049a3794f9a6c348145599d2e5db2)