Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), has been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Minds", and propaganda. The term is used "to denote any action which is practiced mainly by psychological methods with the aim of evoking a planned psychological reaction in other people".

Various techniques are used, and are aimed at influencing a target audience's value system, belief system, emotions, motives, reasoning, or behavior. It is used to induce confessions or reinforce attitudes and behaviors favorable to the originator's objectives, and are sometimes combined with black operations or false flag tactics. It is also used to destroy the morale of enemies through tactics that aim to depress troops' psychological states.

Target audiences can be governments, organizations, groups, and individuals, and is not just limited to soldiers. Civilians of foreign territories can also be targeted by technology and media so as to cause an effect on the government of their country.

Mass communication such as radio allows for direct communication with an enemy populace, and therefore has been used in many efforts. Social media channels and the internet allow for campaigns of disinformation and misinformation performed by agents anywhere in the world.

History

Early

Since prehistoric times, warlords and chiefs have recognized the importance of weakening the morale of their opponents. According to Polyaenus, in the Battle of Pelusium (525 BC) between the Persian Empire and ancient Egypt, the Persian forces used cats and other animals as a psychological tactic against the Egyptians, who avoided harming cats due to religious belief and superstitions.

Currying favor with supporters was the other side of psychological warfare, and an early practitioner of this was Alexander the Great, who successfully conquered large parts of Europe and the Middle East and held on to his territorial gains by co-opting local elites into the Greek administration and culture. Alexander left some of his men behind in each conquered city to introduce Greek culture and oppress dissident views. His soldiers were paid dowries to marry locals in an effort to encourage assimilation.

Genghis Khan, leader of the Mongolian Empire in the 13th century AD employed less subtle techniques. Defeating the will of the enemy before having to attack and reaching a consented settlement was preferable to facing his wrath. The Mongol generals demanded submission to the Khan and threatened the initially captured villages with complete destruction if they refused to surrender. If they had to fight to take the settlement, the Mongol generals fulfilled their threats and massacred the survivors. Tales of the encroaching horde spread to the next villages and created an aura of insecurity that undermined the possibility of future resistance.

Genghis Khan also employed tactics that made his numbers seem greater than they actually were. During night operations he ordered each soldier to light three torches at dusk to give the illusion of an overwhelming army and deceive and intimidate enemy scouts. He also sometimes had objects tied to the tails of his horses, so that riding on open and dry fields raised a cloud of dust that gave the enemy the impression of great numbers. His soldiers used arrows specially notched to whistle as they flew through the air, creating a terrifying noise.

Another tactic favored by the Mongols was catapulting severed human heads over city walls to frighten the inhabitants and spread disease in the besieged city's closed confines. This was especially used by the later Turko-Mongol chieftain.

The Muslim caliph Omar, in his battles against the Byzantine Empire, sent small reinforcements in the form of a continuous stream, giving the impression that a large force would accumulate eventually if not swiftly dealt with.

During the early Qin dynasty and late Eastern Zhou dynasty in 1st century AD China, the Empty Fort Strategy was used to trick the enemy into believing that an empty location was an ambush, in order to prevent them from attacking it using reverse psychology. This tactic also relied on luck, should the enemy believe that the location is a threat to them.

In the 6th century BCE Greek Bias of Priene successfully resisted the Lydian king Alyattes by fattening up a pair of mules and driving them out of the besieged city. When Alyattes' envoy was then sent to Priene, Bias had piles of sand covered with wheat to give the impression of plentiful resources.

This ruse appears to have been well known in medieval Europe: defenders in castles or towns under siege would throw food from the walls to show besiegers that provisions were plentiful. A famous example occurs in the 8th-century legend of Lady Carcas, who supposedly persuaded the Franks to abandon a five-year siege by this means and gave her name to Carcassonne as a result.

During the Granada War, Spanish captain Hernán Pérez del Pulgar routinely employed psychological tactics as part of his guerrilla actions against the Emirate of Granada. In 1490, infiltrating the city by night with a small retinue of soldiers, he nailed a letter of challenge on the main mosque and set fire to the alcaicería before withdrawing.

In 1574, having been informed about the pirate attacks previous to the Battle of Manila, Spanish captain Juan de Salcedo had his relief force return to the city by night while playing marching music and carrying torches in loose formations, so they would appear to be a much larger army to any nearby enemy. They reached the city unopposed.

During the Attack on Marstrand in 1719, Peter Tordenskjold carried out military deception against the Swedes. Although probably apocryphal, he apparently succeeded in making his small force appear larger and feed disinformation to his opponents, similar to the Operations Fortitude and Titanic in World War II.

World War I

The start of modern psychological operations in war is generally dated to World War I. By that point, Western societies were increasingly educated and urbanized, and mass media was available in the form of large circulation newspapers and posters. It was also possible to transmit propaganda to the enemy via the use of airborne leaflets or through explosive delivery systems like modified artillery or mortar rounds.

At the start of the war, the belligerents, especially the British and Germans, began distributing propaganda, both domestically and on the Western front. The British had several advantages that allowed them to succeed in the battle for world opinion; they had one of the world's most reputable news systems, with much experience in international and cross-cultural communication, and they controlled much of the undersea communications cable system then in operation. These capabilities were easily transitioned to the task of warfare.

The British also had a diplomatic service that maintained good relations with many nations around the world, in contrast to the reputation of the German services. While German attempts to foment revolution in parts of the British Empire, such as Ireland and India, were ineffective, extensive experience in the Middle East allowed the British to successfully induce the Arabs to revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

In August 1914, David Lloyd George appointed a Member of Parliament (MP), Charles Masterman, to head a Propaganda Agency at Wellington House. A distinguished body of literary talent was enlisted for the task, with its members including Arthur Conan Doyle, Ford Madox Ford, G. K. Chesterton, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling and H. G. Wells. Over 1,160 pamphlets were published during the war and distributed to neutral countries, and eventually, to Germany. One of the first significant publications, the Report on Alleged German Outrages of 1915, had a great effect on general opinion across the world. The pamphlet documented atrocities, both actual and alleged, committed by the German army against Belgian civilians. A Dutch illustrator, Louis Raemaekers, provided the highly emotional drawings which appeared in the pamphlet.

In 1917, the bureau was subsumed into the new Department of Information and branched out into telegraph communications, radio, newspapers, magazines and the cinema. In 1918, Viscount Northcliffe was appointed Director of Propaganda in Enemy Countries. The department was split between propaganda against Germany organized by H.G Wells, and propaganda against the Austro-Hungarian Empire supervised by Wickham Steed and Robert William Seton-Watson; the attempts of the latter focused on the lack of ethnic cohesion in the Empire and stoked the grievances of minorities such as the Croats and Slovenes. It had a significant effect on the final collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto.

Aerial leaflets were dropped over German trenches containing postcards from prisoners of war detailing their humane conditions, surrender notices and general propaganda against the Kaiser and the German generals. By the end of the war, MI7b had distributed almost 26 million leaflets. The Germans began shooting the leaflet-dropping pilots, prompting the British to develop unmanned leaflet balloons that drifted across no-man's land. At least one in seven of these leaflets were not handed in by the soldiers to their superiors, despite severe penalties for that offence. Even General Hindenburg admitted that "Unsuspectingly, many thousands consumed the poison", and POWs admitted to being disillusioned by the propaganda leaflets that depicted the use of German troops as mere cannon fodder. In 1915, the British began airdropping a regular leaflet newspaper Le Courrier de l'Air for civilians in German-occupied France and Belgium.

At the start of the war, the French government took control of the media to suppress negative coverage. Only in 1916, with the establishment of the Maison de la Presse, did they begin to use similar tactics for the purpose of psychological warfare. One of its sections was the "Service de la Propagande aérienne" (Aerial Propaganda Service), headed by Professor Tonnelat and Jean-Jacques Waltz, an Alsatian artist code-named "Hansi". The French tended to distribute leaflets of images only, although the full publication of US President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, which had been heavily edited in the German newspapers, was distributed via airborne leaflets by the French.

The Central Powers were slow to use these techniques; however, at the start of the war the Germans succeeded in inducing the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire to declare 'holy war', or Jihad, against the Western infidels. They also attempted to foment rebellion against the British Empire in places as far afield as Ireland, Afghanistan, and India. The Germans' greatest success was in giving the Russian revolutionary, Lenin, free transit on a sealed train from Switzerland to Finland after the overthrow of the Tsar. This soon paid off when the Bolshevik Revolution took Russia out of the war.

World War II

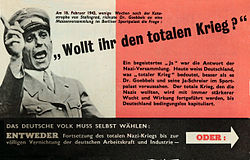

Adolf Hitler was greatly influenced by the psychological tactics of warfare the British had employed during World War I, and attributed the defeat of Germany to the effects this propaganda had on the soldiers. He became committed to the use of mass propaganda to influence the minds of the German population in the decades to come. By calling his movement The Third Reich, he was able to convince many civilians that his cause was not just a fad, but the way of their future. Joseph Goebbels was appointed as Propaganda Minister when Hitler came to power in 1933, and he portrayed Hitler as a messianic figure for the redemption of Germany. Hitler also coupled this with the resonating projections of his orations for effect.

Germany's Fall Grün plan of invasion of Czechoslovakia had a large part dealing with psychological warfare aimed both at the Czechoslovak civilians and government as well as, crucially, at Czechoslovakia's allies. It became successful to the point that Germany gained support of UK and France through appeasement to occupy Czechoslovakia without having to fight an all-out war, sustaining only minimum losses in covert war before the Munich Agreement.

At the start of the Second World War, the British set up the Political Warfare Executive to produce and distribute propaganda. Through the use of powerful transmitters, broadcasts could be made across Europe. Sefton Delmer managed a successful black propaganda campaign through several radio stations which were designed to be popular with German troops while at the same time introducing news material that would weaken their morale under a veneer of authenticity. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill made use of radio broadcasts for propaganda against the Germans. Churchill favoured deception; he said "In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.".

During World War II, the British made extensive use of deception – developing many new techniques and theories. The main protagonists at this time were 'A' Force, set up in 1940 under Dudley Clarke, and the London Controlling Section, chartered in 1942 under the control of John Bevan. Clarke pioneered many of the strategies of military deception. His ideas for combining fictional orders of battle, visual deception and double agents helped define Allied deception strategy during the war, for which he has been referred to as "the greatest British deceiver of WW2".

During the lead-up to the Allied invasion of Normandy, many new tactics in psychological warfare were devised. The plan for Operation Bodyguard set out a general strategy to mislead German high command as to the date and location of the invasion, which was obviously going to happen. Planning began in 1943 under the auspices of the London Controlling Section (LCS). A draft strategy, referred to as Plan Jael, was presented to Allied high command at the Tehran Conference. Operation Fortitude was intended to convince the Germans of a greater Allied military strength than was the case, through fictional field armies, faked operations to prepare the ground for invasion and "leaked" misinformation about the Allied order of battle and war plans.

Elaborate naval deceptions (Operations Glimmer, Taxable and Big Drum) were undertaken in the English Channel. Small ships and aircraft simulated invasion fleets lying off Pas de Calais, Cap d'Antifer and the western flank of the real invasion force. At the same time Operation Titanic involved the RAF dropping fake paratroopers to the east and west of the Normandy landings.

The deceptions were implemented with the use of double agents, radio traffic and visual deception. The British "Double Cross" anti-espionage operation had proven very successful from the outset of the war, and the LCS was able to use double agents to send back misleading information about Allied invasion plans. The use of visual deception, including mock tanks and other military hardware had been developed during the North Africa campaign. Mock hardware was created for Bodyguard; in particular, dummy landing craft were stockpiled to give the impression that the invasion would take place near Calais.

The Operation was a strategic success and the Normandy landings caught German defences unaware. Continuing deception, portraying the landings as a diversion from a forthcoming main invasion in the Calais region, led Hitler into delaying transferring forces from Calais to the real battleground for nearly seven weeks.

Vietnam War

The United States ran an extensive program of psychological warfare during the Vietnam War. The Phoenix Program had the dual aim of assassinating National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF or Viet Cong) personnel and terrorizing any potential sympathizers or passive supporters. During the Phoenix Program, over 19,000 NLF supporters were killed. In Operation Wandering Soul, the United States also used tapes of distorted human sounds and played them during the night making the Vietnamese soldiers think that the dead were back for revenge.

The Vietcong and their forces also used a program of psychological warfare during this war. Trịnh Thị Ngọ, also known as Thu Hương and Hanoi Hannah, was a Vietnamese radio personality. She made English-language broadcasts for North Vietnam directed at United States troops. During the Vietnam War, Ngọ became famous among US soldiers for her propaganda broadcasts on Radio Hanoi. Her scripts were written by the North Vietnamese Army and were intended to frighten and shame the soldiers into leaving their posts. She made three broadcasts a day, reading a list of newly killed or imprisoned Americans, and playing popular US anti-war songs in an effort to incite feelings of nostalgia and homesickness, attempting to persuade US GIs that the US involvement in the Vietnam War was unjust and immoral. A typical broadcast began as follows:

How are you, GI Joe? It seems to me that most of you are poorly informed about the going of the war, to say nothing about a correct explanation of your presence over here. Nothing is more confused than to be ordered into a war to die or to be maimed for life without the faintest idea of what's going on.

21st century

The CIA made extensive use of Contra soldiers to destabilize the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The CIA used psychological warfare techniques against the Panamanians by delivering unlicensed TV broadcasts. The United States government has used propaganda broadcasts against the Cuban government through TV Marti, based in Miami, Florida. However, the Cuban government has been successful at jamming the signal of TV Marti.

In the Iraq War, the United States used the shock and awe campaign to psychologically maim and break the will of the Iraqi Army to fight.

In cyberspace, social media has enabled the use of disinformation on a wide scale. Analysts have found evidence of doctored or misleading photographs spread by social media in the Syrian Civil War and 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, possibly with state involvement. Military and governments have engaged in psychological operations (PSYOP) and informational warfare (IW) on social networking platforms to regulate foreign propaganda, which includes countries like the US, Russia, and China.

In 2022, Meta and the Stanford Internet Observatory found that over five years people associated with the U.S. military, who tried to conceal their identities, created fake accounts on social media systems including Balatarin, Facebook, Instagram, Odnoklassniki, Telegram, Twitter, VKontakte and YouTube in an influence operation in Central Asia and the Middle East. Their posts, primarily in Arabic, Farsi and Russian, criticized Iran, China and Russia and gave pro-Western narratives. Data suggested the activity was a series of covert campaigns rather than a single operation.

In operations in the South and East China Seas, both the United States and China have been engaged in "cognitive warfare", which involves displays of force, staged photographs and sharing disinformation. The start of the public use of "cognitive warfare" as a clear movement occurred in 2013 with China's political rhetoric.

Methods

Most modern uses of the term psychological warfare refer to the following military methods:

- Demoralization:

- Distributing pamphlets that encourage desertion or supply instructions on how to surrender.

- Shock and awe military strategy.

- Projecting repetitive and disturbing noises and music for long periods at high volume towards groups under siege like during Operation Nifty Package.

- Propaganda radio stations, such as Lord Haw-Haw in World War II on the "Germany calling" station.

- False flag events.

- Terrorism

- The threat of chemical weapons.

- Information warfare.

Most of these techniques were developed during World War II or earlier, and have been used to some degree in every conflict since. Daniel Lerner was in the OSS (the predecessor to the American CIA) and in his book, attempts to analyze how effective the various strategies were. He concludes that there is little evidence that any of them were dramatically successful, except perhaps surrender instructions over loudspeakers when victory was imminent. Measuring the success or failure of psychological warfare is very hard, as the conditions are very far from being a controlled experiment.

Lerner also divides psychological warfare operations into three categories:

- White propaganda (omissions and emphasis): Truthful and not strongly biased, where the source of information is acknowledged.

- Grey propaganda (omissions, emphasis and racial/ethnic/religious bias): Largely truthful, containing no information that can be proven wrong; the source is not identified.

- Black propaganda (commissions of falsification): Inherently deceitful, information given in the product is attributed to a source that was not responsible for its creation.

Lerner says grey and black operations ultimately have a heavy cost, in that the target population sooner or later recognizes them as propaganda and discredits the source. He writes, "This is one of the few dogmas advanced by Sykewarriors that is likely to endure as an axiom of propaganda: Credibility is a condition of persuasion. Before you can make a man do as you say, you must make him believe what you say." Consistent with this idea, the Allied strategy in World War II was predominantly one of truth (with certain exceptions).

In Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, Jacques Ellul discusses psychological warfare as a common peace policy practice between nations as a form of indirect aggression. This type of propaganda drains the public opinion of an opposing regime by stripping away its power on public opinion. This form of aggression is hard to defend against because no international court of justice is capable of protecting against psychological aggression since it cannot be legally adjudicated.

"Here the propagandists is [sic] dealing with a foreign adversary whose morale he seeks to destroy by psychological means so that the opponent begins to doubt the validity of his beliefs and actions."

Terrorism

According to Boaz Ganor, terrorism weakens the sense of security and disturbs daily life, damaging the target country's capability to function. Terrorism is a strategy that aims to influence public opinion into pressuring leaders to give in to the terrorists' demands, and the population becomes a tool to advance the political agenda.

By country

China

According to U.S. military analysts, attacking the enemy's mind is an important element of the People's Republic of China's military strategy. This type of warfare is rooted in the Chinese Stratagems outlined by Sun Tzu in The Art of War and Thirty-Six Stratagems. In its dealings with its rivals, China is expected to utilize Marxism to mobilize communist loyalists, as well as flex its economic and military muscle to persuade other nations to act in the Chinese government's interests. The Chinese government also tries to control the media to keep a tight hold on propaganda efforts for its people. The Chinese government also utilizes cognitive warfare against Taiwan.

France

The Centre interarmées des actions sur l'environnement is an organization made up of 300 soldiers whose mission is to assure to the four service arm of the French Armed Forces psychological warfare capacities. Deployed in particular to Mali and Afghanistan, its missions "consist in better explaining and accepting the action of French forces in operation with local actors and thus gaining their trust: direct aid to the populations, management of reconstruction sites, actions of communication of influence with the population, elites and local elected officials". The center has capacities for analysis, influence, expertise and instruction.

Germany

In the German Bundeswehr, the Zentrum Operative Kommunikation is responsible for PSYOP efforts. The center is subordinate to the Cyber and Information Domain Service branch alongside multiple IT and Electronic Warfare battalions and consists of around 1000 soldiers. One project of the German PSYOP forces is the radio station Stimme der Freiheit (Sada-e Azadi, Voice of Freedom), heard by thousands of Afghans. Another is the publication of various newspapers and magazines in Kosovo and Afghanistan, where German soldiers serve with NATO.

Iran

The Iranian government had an operation program to use the 2022 FIFA World Cup as a psyop against concurrent people's protests.

Israel

The Israeli government and its military make use of psychological warfare. In 2021, Israeli newspaper Haaretz revealed that "Abu Ali Express", a popular news page on Telegram and Twitter purportedly dedicated to "Arab affairs", was actually run by a Jewish Israeli paid consultant to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). The IDF's psyops account had been the source of a number of noteworthy reports that were afterwards cited by the Israeli and international media.

Russia

Soviet Union

United Kingdom

The British were one of the first major military powers to use psychological warfare in the First and Second World Wars. In the current British Armed Forces, PsyOps are handled by the tri-service 15 Psychological Operations Group. (See also MI5 and Secret Intelligence Service). The Psychological Operations Group comprises over 150 personnel, approximately 75 from the regular Armed Services and 75 from the Reserves. The Group supports deployed commanders in the provision of psychological operations in operational and tactical environments.

The Group was established immediately after the 1991 Gulf War, has since grown significantly in size to meet operational requirements, and since 2015 has been one of the sub-units of the 77th Brigade, formerly called the Security Assistance Group.

In June 2015, NSA files published by Glenn Greenwald revealed details of the JTRIG group at British intelligence agency GCHQ covertly manipulating online communities. This is in line with JTRIG's goal: to "destroy, deny, degrade [and] disrupt" enemies by "discrediting" them, planting misinformation and shutting down their communications.

In March 2019, it emerged that the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) of the UK's Ministry of Defence (MoD) is tendering to arms companies and universities for £70M worth of assistance under a project to develop new methods of psychological warfare. The project is known as the human and social sciences research capability (HSSRC).

United States

The term psychological warfare is believed to have migrated from Germany to the United States in 1941. During World War II, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff defined psychological warfare broadly, stating "Psychological warfare employs any weapon to influence the mind of the enemy. The weapons are psychological only in the effect they produce and not because of the weapons themselves." The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) currently defines psychological warfare as:

"The planned use of propaganda and other psychological actions having the primary purpose of influencing the opinions, emotions, attitudes, and behavior of hostile foreign groups in such a way as to support the achievement of national objectives."

This definition indicates that a critical element of the U.S. psychological operations capabilities includes propaganda and by extension counterpropaganda. Joint Publication 3–53 establishes specific policy to use public affairs mediums to counter propaganda from foreign origins.

The purpose of United States psychological operations is to induce or reinforce attitudes and behaviors favorable to US objectives. The Special Activities Center (SAC) is a division of the Central Intelligence Agency's Directorate of Operations, responsible for Covert Action and "Special Activities". These special activities include covert political influence (which includes psychological operations) and paramilitary operations. SAC's political influence group is the only US unit allowed to conduct these operations covertly and is considered the primary unit in this area.

Dedicated psychological operations units exist in the United States Army and United States Marine Corps. The United States Navy and the 193rd Special Operations Wing of the United States Air Force also plans and executes limited PSYOP missions. United States PSYOP units and soldiers of all branches of the military are prohibited by law from targeting U.S. citizens with PSYOP within the borders of the United States (Executive Order S-1233, DOD Directive S-3321.1, and National Security Decision Directive 130). While United States Army PSYOP units may offer non-PSYOP support to domestic military missions, they can only target foreign audiences.

A U.S. Army field manual released in January 2013 states that "Inform and Influence Activities" are critical for describing, directing, and leading military operations. Several Army Division leadership staff are assigned to “planning, integration and synchronization of designated information-related capabilities."

In September 2022, the DoD launched an audit of covert information warfare after social media companies identified a suspected U.S. military operation.